Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 502

January 16, 2013

Launching Football is a Country

For a while we’ve dabbled with sports blogging on Africa is a Country; i.e. pieces on John Terry, Didier Drogba, black jockeys and, now and again, when we’ve compiled one of our beloved lists. But now we’ve decided to try to up the ante and today we’re launching (with not much fanfare since we still need to convince you about how excellent this will all be, but drumroll please …) a new page on the site: Football is a Country. Once we relaunch with a new design (coming sooner than you think, promise) it will be better organized. The big idea behind the page is to present a more global, postcolonial (for want for a better word) take on world football. The main focus of the page for the foreseeable future will be African football. What that means is quite broad — both the categories of “African” and “football” will be pretty elastic.

For a while we’ve dabbled with sports blogging on Africa is a Country; i.e. pieces on John Terry, Didier Drogba, black jockeys and, now and again, when we’ve compiled one of our beloved lists. But now we’ve decided to try to up the ante and today we’re launching (with not much fanfare since we still need to convince you about how excellent this will all be, but drumroll please …) a new page on the site: Football is a Country. Once we relaunch with a new design (coming sooner than you think, promise) it will be better organized. The big idea behind the page is to present a more global, postcolonial (for want for a better word) take on world football. The main focus of the page for the foreseeable future will be African football. What that means is quite broad — both the categories of “African” and “football” will be pretty elastic.

As you can imagine, we take into account the forces of migration, media and identity politics. We promise the writing will be witty and insightful, alive to the history of the game and its social and political resonances, and we will not be afraid to make a bit of mischief where necessary. Check out our embryonic Facebook page for a taster of the kinds of things we’ll be covering.

The timing is perfect: this Saturday, January 19th, sees the start of the African Cup of Nations (we’ll explain why Zambia only gets to be cup holders for one year in a follow-up post).

Like AIAC, Football is a Country is going to be a collaborative effort, and (in true Africa is a Country tradition) we’ve already roped in a stellar cast of contributors. Also watch out for more football (for the Americans: soccer) tweets at the Africa is a Country account.

The F.i.a.C. Editors

Elliot Ross and Sean Jacobs

What kind of home is the “Home Office” anyway?

Roseline Akhalu (Image Source)

Why do they call it the Home Office, when that agency dedicates its resources to expelling, incarcerating, and generally despising precisely those who need help? What kind of home is that, anyway? In 2004, Roseline Akhalu was one of 23 people to win a Ford Foundation scholarship to study in England. That would be enough to celebrate in itself, but Akhalu’s story is one of extraordinary pain and perseverance. Five years earlier, she and her husband were working in Benin City, Nigeria. Her husband was a nurse, and Roseline Akhalu worked for the local government. They didn’t earn much but they got by. Until March 1999, when her husband was diagnosed with a brain tumor. The couple was told that they must go to South Africa, or India, for care, but the costs of such a venture were prohibitive. And so Roseline Akhalu watched her husband die because there was no money.

Now a widow, and a widow without a child, Akhalu confronted a hostile future. After her in-laws took pretty much everything, Roseline Akhalu set about the work of making a life for herself. She worked, she studied, she applied for a masters’ scholarship, and she succeeded.

Akhalu went to Leeds University, to study Development Studies. She joined a local church; she tended her gardens, saving tomatoes that were otherwise destined to die; she worked with young girls in the area. She planned to return to Nigeria and establish an NGO to work with young girls. It was all planned.

Until she was diagnosed with kidney failure. That was 2004, a few months after arriving. In 2005, Akhalu was put on regular dialysis. In 2009, she had a successful kidney transplant, but the transplant meant that for the rest of her life Roseline Akhalu would need hospital check-ups and immunosuppressant drugs. In Nigeria, those drugs would be impossibly costly.

Her attorney informed the government of her change in status, that due to unforeseen circumstances Roseline Akhalu, who had never planned on staying in the United Kingdom, now found that, in order to live, she had to stay.

And so began Roseline Akhalu’s journey into the uncanny unheimlich of the Home Office, where home means prison or exile, and nothing says “compassion” like humiliation, degradation and persecution.

Once a month, Akhalu showed up, in Leeds, at the United Kingdom Border Agency Reporting Office. Then, in March of 2012, without explanation, she was detained and immediately packed off, by Reliance ‘escorts’, to the notorious Yarl’s Wood, where she was treated like everyone’s treated at Yarl’s Wood, and especially women…disgustingly.

So far this is business as usual. Here’s where it gets interesting. In May, Akhalu was released from detention. In September, the Home Office refused her appeal. In November, a judge overturned the Home Office decision. The judge declared that, since Akhalu had established a private life of value to her, to members of the Church, and to a wider community, removing her would violate her right to a private and family life protected by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The judge noted that Akhalu had done absolutely nothing illegal. She had come to the United Kingdom legally and was diagnosed while legally in the country. Most chillingly, perhaps, the judge agreed that to send Roseline Akhalu back to Nigeria was a swift death sentence. Given the health care system and costs in Nigeria, she would be dead within four weeks. Nigerian and English doctors agreed.

On December 14, the Home Office appealed the decision. That’s right. They’re pursuing a case against Roseline Akhalu, despite all the evidence and mounting pressure from all sides. Why? Because that’s what the Home Office does. Want an example? In 2008, Ama Sumani, a 43-year old Ghanaian woman, was lying in hospital in Cardiff, in Wales, receiving kidney dialysis for malignant myeloma. That was until the good old boys showed up and hauled her out and then shipped her off to Ghana, where she died soon after. The Lancet put it neatly: “The UK has committed an atrocious barbarism.” That was January 19, 2008. Five years later, almost to the day…the atrocity continues.

The ‘Promised Land’ in Mozambique

Sadira Joaquim works on her family’s farmland. Instead of the initially promised two hectares of productive farmland, families were given only one hectare of unproductive farmland—hardly enough to support a family, let alone sell produce on the far away markets. Sadira is only 20 years old and has no other possibilities to work, unlike in Moatize.

Promised Land is the title of the German photographer Gregor Zielke’s feature about the relocation of 700 families in Mozambique’s Tete province to make space for the Brazilian company Vale’s construction of the world’s second largest coalmine. The New York Times recently covered the plight of the people in Cateme following relocation. Gregor Zielke’s photos capture the company’s broken promises—unproductive farmland and poorly constructed settlements—but also the communities’ resilience. Gregor Zielke is part of a cooperative of photographers that have been working in Mozambique for some time and seek to advance dialogue and better understanding between Germany and Mozambique by producing media reports and developing educational projects.

Why did you call your photo feature “Promised Land”?

“Promised Land” refers to the fact that people lose their land, the land they had inhabited for generations, to a company which promised better living conditions and farmland for self-sustainment through resettlement—and the people there are very tied to their land. But looking at the conditions now you recognize that it is a promise that has not been fulfilled. For example, people were promised two hectares of productive farmland but only received one hectare of unproductive farmland hours away from their houses, which isn’t even enough to feed their own families. Houses are built cheaply and show cracks after only one or two years. Of course, at first glance they seem better than mud huts, but they’re just not suited for the area and the families. The communities’ infrastructure is completely gone, at least so far away that they simply cannot afford going there on a regular basis. The land is unbelievably hot and dry, even for Tete Province where life has always been hard anyways. Obviously, “Promised Land” also plays with the biblical term and how much of an odyssey the whole resettlement process is that people go through.

This is a typical street in Cateme, wide and dusty. Walks to the wells are far, especially when carrying 20 liters of water. The whole area is more or less deserted, ground water has to be pumped by electrical pumps because it’s so deep, so when the electricity goes down there is also no water.

What sparked your interest in Mozambique, and in Cateme in particular?

I think that Mozambique is a good example of how the local population doesn’t benefit from the current resource boom in Africa, similar things are happening in many other countries too. Kind of like the return of the colonial era. I think it’s an important issue to talk about and raise international awareness, on the other hand it’s just as important to inform the displaced communities about their rights and raise resistance so that there at least can be better consultation with the local communities in the future. You can’t really blame the government for exploring the resources; but they should be used to generate sustainable development on a local and national level. That’s just not happening. Living conditions worsened.

How did you prepare for the trip?

I worked with the Mozambican NGO Justiça Ambiental/Friends of the Earth Mozambique (JA!) that made it possible to work in the resettlement. They have very good contacts and work in the region in the field of human rights and environmental issues. Without them, the work simply wouldn’t have been possible. There’s a lot of red tape, and getting permission from the local administration and local leaders to work in Cateme was uncertain until the last minute. In fact, we spent quite a bit of time of the two weeks we were there getting permission before we could even start working in the area. JA! also opened the doors to the families in Cateme; of course there is a lot of distrust and also fear. The families in Cateme needed to understand what we were about to do, what side we were on. They were suspicious of what we were going to report from Cateme, afraid we could make it look beneficial for the people, favorable for Vale and the government. Some even thought that we had been hired by Vale. But after initial concern they were very giving and open.

This man works in a brick manufacture near Moatize. Along with his colleagues, he was resettled to Cateme and went back to Moatize because otherwise he is simply unable to support his family. They stay in the mud pit five days a week and only return to their families on the weekends because their workplace now is 40 kilometers from their homes. They sleep in the mud pit or by the ovens. They have no choice. This illustrates quite clearly how little care is being taken in the whole resettlement process.

What did you plan on capturing with your photos?

My aim was to document people’s struggle in daily life and how they deal with these difficult circumstances—I was amazed at how people still make the best of their situation and try to cope with it. The problems these communities face are on so many different levels and not always very obvious—they’re basically sent to the desert without adequate housing, health care and—most importantly—no possibilities for self-sustainment. Most of them are farmers, they live off their land and sell their produce on the markets, now the markets are more than 40 kilometers away and people don’t have any surplus produce to sell due to the unproductive farmland they were given. They depend on their land. That really robs them of their existence.

What impressed you most about how the people dealt with their worsened living conditions?

The most amazing moment for me was to see people dancing on a Sunday afternoon a few kilometers from Cateme in Mwaladzi, a community resettled by the British mining company Rio Tinto. There is no electricity and no water supply and people have to rely on a water truck that comes once a week. Two boys had put up some kind of karaoke machine blasting music, powered by a solar panel they got somewhere. Adults and children alike were dancing and enjoying themselves inviting me to join them.

[image error]

Students hang around after school at Armando Guebuza School in Cateme. The school is a so-called “white elephant”: theoretically it brings education and infrastructure to the resettlement, but in reality not many families can afford the high school and examination turning the school into a de facto boarding school for students from other communities. Only approximately 10 percent of students come from Cateme resettlement.

How do you aspire to influence political debates with your work?

My aim is simply to put faces to the displaced communities, to show that the big companies are not moving around figures and a nameless “population.” They have names, they are mothers, fathers, grandparents and kids, all they want is to raise their families. That’s not asking much, is it?

You also conducted a project on the urbanization process of villages in eastern China. Do you see any parallels between the transformation processes in Mozambique and those you observed in eastern China?

The process of resettlement in China is very different to Mozambique, the reasons and circumstances are very different. However, any kind of imposed resettlement usually means a drastic change in the living conditions. In China as well as in Mozambique people have to adapt to the changes and eventually find new ways of self-sustainment. You see many people in China’s rapidly growing cities still fishing in rivers and canals and using other natural resources they find by the roadside, mostly because they just do the things they’re used to and might have difficulties adapting to a new lifestyle. In Mozambique such things may even be a matter of survival.

The Joaquim family enjoys a little cooling down after sunset. Houses are not built to people’s needs and are of poor quality. The tin clad roofs heat up the houses to temperatures of over 60°C inside and show cracks after only one or two years. Though the area is very dry, occasional rains leak in the houses, leaving inhabitants to seek shelter in the school.

* All photo captions written by the photographer.

January 15, 2013

An Ode to The Mahogany Room in Cape Town

“YOU might call me a catalyst. A catalyst changes everything, but it remains unchanged” — Sun Ra

“YOU might call me a catalyst. A catalyst changes everything, but it remains unchanged” — Sun Ra

In just under a year, 79 Buitenkant Street in central Cape Town (around the corner from the country’s Parliament) has become an address synonymous with hosting the best jazz events in South Africa. It’s home to the The Mahogany Room. Currently mainly offering live jazz Wednesdays through Saturdays, the venue is somewhat of a mecca for jazz heads seeking a bit more engagement with their beloved music. With a seated capacity of about fifty, The Mahogany Room has consistently served up copious amounts of musical excellence, with one event upstaging the next on the rail-road to jazz supremacy. I have been fortunate to attend my fair share of shows at the venue. Often-times, I find myself hard-pressed to write my feelings down while the music lacerates my conscience. What follows are thoughts that went through my head as pianist Afrika Mkhize evoked roars amongst patrons of what is supposed to be a ‘quiet, seated venue’; my feelings when Mark Fransman’s chair lit an invisible fire under him, forcing him to jump ceaselessly across its width. This is what went through my mind as Kesivan Naidoo, eyes open wide and gazing into a distant future, performed a creation myth using only his drumsticks, beating life into his drumkit in the process.

Afrika Mkhize (Photo by Jonx Pillemer)

The audience, feeling short-charged with merely clapping, shouts ‘yeah’ and ‘ooh’ in approval, along with muted sounds of approval which provide the perfect pretext for this communal gathering. Jazz is indeed for the masses, and the masses are consumed by this experience.

The next tune is called “Xenza,” an homage to the people of the Eastern Cape. The swiveling double bass precedes what is sounding like a gargantuan manifestation which belies the tiny, choking confines of time and space. I am taken back to Zim Ngqawana … — the unfamiliarity of it all, and how I grew to appreciate its place in the music. It morphs into a piano-bass battle akin to Westerns or Kung-fu flicks. Then Buddy Wells’s horn slides in; he has a knack for taking his time, searching for the right groove, letting it linger before he goes in for the kill. Mkhize is like a modern-day Monk in that mouthing thing that he does. He is uneasy, hitting hi-brow and low-tide, unleashing hours of practice with impeccable excellence. He talks to the piano — it could be the wine taking effect. Either way, he is a marvel, a dizzying cross between the late Moses Molelekwa and Monk; head-jerking motions, and a momentary brow-wipe with the left hand while the right performs its dutiful construction. Listen to the percussive passage of Naidoo, its Willie Bobo-esque exquisiteness. It’s only him and Wells now. Wells completes his part, then motions towards Mkhize. Mkhize, eyes closed, head in another dimension, gives the music time to get ingested before proceeding to rumbunctiously punch the keys in a free-form approach. Listen to that staccato thing he does, this man is fierce. Look at his contorted face, hear how the up-and-down-scale flourishes sound from the vantage point of the listener. Respect the architects, and acknowledge the reference he’s just made to Trane’s “Love supreme.”

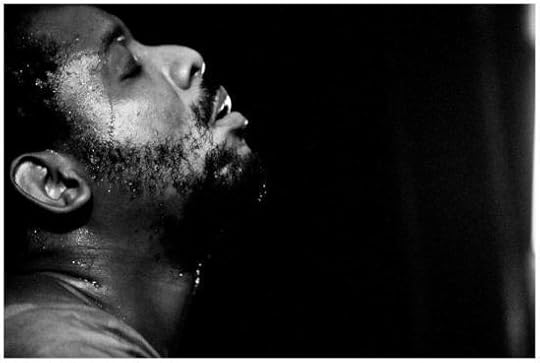

Kesivan Naidoo (Photo by Jonx Pillemer)

Kesivan Naidoo, the trenchcoat overbearer, lord of cymbals, master of the beat and purger of demons; one-man trenchcoat mafioso with a hat to match. “It is the look that counts,” said an uncredited source now blown away into the annals of time. It is the look exhibited by soloists navigating the subtext of their musical terrain, transporting on-lookers into depths of the unknown. That same look refuses to name nor contain that space, but rather allows the on-looker to provide his/her own interpretation.

Gogwana [in the photo above] and Xonti, the Dizzy and Bird of South African jazz, foundation-keepers with a forward-thinking frame of mind. Thandi Ntuli, madame extraordinaire of rhythm, occupies her spot at the piano. Moses stretches forth his hand during her solo, immersing her already-capable hands int o a maze of amazing condiments, leaving a belleaguered set of on-lookers in her wake.

Gogwana [in the photo above] and Xonti, the Dizzy and Bird of South African jazz, foundation-keepers with a forward-thinking frame of mind. Thandi Ntuli, madame extraordinaire of rhythm, occupies her spot at the piano. Moses stretches forth his hand during her solo, immersing her already-capable hands int o a maze of amazing condiments, leaving a belleaguered set of on-lookers in her wake.

“Ukuz’khangela”: finding oneself, the balance between the imagined, scripted, and an escape from the framed, directed. Bossa Nova goes to Mdantsane, ruminates with the legends: Stompi Mavi, Ezra Ngcukana — the influencers of those who influence. Listen to that bass, pay close attention to what it is doing; listen to the scales, acknowledge them, but transcend. What we have here is not just an amalgamation of notes, but an interplay between the emotive and the metaphysical. These musicians are giving birth on-stage, de- constructing conventional wisdom, migrating into the domain of free-thinkers who are also doers. Doers free-thinking, paving the way to free-doing? Freedom?

“Yakhal’inkomo”: an intermittent intervention of Winston the Great. Ngozi, your presence is sorely missed. See what Lwanda’s doing on his horn, hear what Xonti’s doing on his? That is all for you Bra Winston, to let you know that, though you are reported to have been ‘humble’ and ‘rarely gave interviews’, there clearly was no need to, for your music spoke — and continues to speak — on your behalf.

Benjamin Jephta holds his iPhone in hand to help him tune his upright bass. It is a mere glimpse into the changing times in jazz music. Mark Fransman, bandleader supreme [photo above], scurries about the room looking for the perfect spot for his camera to capture the show — so tired, it seems, have jazz musicians become of other people’s (mis)representation of them that they have taken matters into their own hands, charted their course so to say.

Benjamin Jephta holds his iPhone in hand to help him tune his upright bass. It is a mere glimpse into the changing times in jazz music. Mark Fransman, bandleader supreme [photo above], scurries about the room looking for the perfect spot for his camera to capture the show — so tired, it seems, have jazz musicians become of other people’s (mis)representation of them that they have taken matters into their own hands, charted their course so to say.

Hugh Masekela and Larry Willis (Photo by Jonx Pillemer)

To see musicians up-close, to witness their musical cues, to hear them breathe…this is the greatest advantage of the Mahogany. The feeling of being a part of a bigger whole, of being included in an inner circle of melody, rhythm, and groove. Being part of the universal whole; this is what it’s all about. I may have missed Bra Hugh and Larry Willis’s performance; Kyle Shepherd was launching his album on the other side of town when Soweto Kinch performed; and life had other plans for me when Tutu Puoane came to town and did a three-day residency. It still doesn’t sit well with me that I missed Shepherd’s special collaboration with avant-garde jazz drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo, but it surely has been one hell of a year!

Africa’s billionaires are a national elite (and they’re awesome)

Forbes Magazine recently released its second annual list of “Africa’s 40 Richest” people. The feature appeared on the Forbes homepage alongside lists of “America’s Richest,” “India’s Richest,” “Thailand’s Richest,” and “China’s Richest.” For Forbes, it seems, Africa is indeed a country (it’s the only place where the richest are grouped by continent and not countries), and an increasingly wealthy one at that.

The Forbes list is just the latest example of the current dominant Western press narrative regarding Africa: the continent as “emerging economy.” Forbes does, however, avoid one problem that characterizes many other recent writings about African economic growth: it acknowledges the deeply unequal distribution of wealth on the continent. It does this not by citing Gini coefficients or talking about poverty, but by explicitly celebrating the grotesque wealth of the few. Indeed, while other authors traffic in broad narratives of “Africa rising,” the compilers of the Forbes list are more interested in Africans rising.

Of course the success of the 38 men and 2 women included on the list, and the fact that “the moguls’ combined net worth…is up 12% over last year,” is taken as an implicit sign that Africa as a whole is improving. “Amid grim news about the global economy, Africa continues to shine,” begins the article introducing the list.

Every good capitalist economy, it seems, needs its oligarchs. Far be it for Forbes to question whether the money could be distributed differently, to probe how those on the list acquired their assets in the first place, or to look at those who got pushed down during the moguls’ climb to the top. Indeed, if one takes Forbes’ word for it, it seems that Africa’s billionaires are, without exception, awesome.

Topping the list, for instance, is Nigerian construction and telecom magnate Aliko Dangote, with a net worth of $12 billion in 2012. This is up from $10.1 billion in 2011 and good for 76th richest person in the world. Dangote, we are quickly told, is working with Bill Gates to fight polio.

Indeed, one might be forgiven for wondering if the entire purpose of the Forbes list (or Forbes more generally for that matter) is to humanize billionaires, allowing the rest of us to see them as people (rather than as walking embodiments of economic injustice). How else to explain the fact that Forbes finds space in its 70 word profile of Nicky Oppenheimer, Africa’s second wealthiest person, to tell us that he is an “avid cricketer”? Or the rather bizarre editorial selection of a picture of Africa’s third richest man, Johann Rupert, swinging a golf club to accompany his write-up?

Now, I should say that I did a good deal of digging around for dirt on everyone in the top ten of the Forbes list and didn’t come up with much. Whether this speaks to a heretofore undiscovered correlation between ethics and obscene amounts of wealth, or just to excellent corporate PR and Google policing, is hard to say. Oppenheimer and Rupert’s families did build their fortunes under apartheid, but both men and their fathers have made sure to highlight that they “spoke out” against the National Party’s racist regime. Construction magnate Naseef Sawiris of Egypt did amass his money under the Mubarak military dictatorship, but, according to TIME magazine (who else), Sawiris “has a reputation for personal integrity, being a strong nationalist with a liberal vision of Egypt’s future”; so much so that he is one of the few Egyptian oligarchs not to have his assets frozen in the wake of last year’s Revolution.

I won’t speculate on the means by which Africa’s billionaires acquired their wealth. I have no evidence that they are anything other than fine upstanding citizens, and to imply otherwise could be libelous. (Though I can’t help thinking of an old expression involving eggs and omelets.) I will, however, say that I find their mere existence to be not, as Forbes would have us believe, positive evidence of “Africa rising,” but testament to the extreme inequality that characterizes economic growth on the continent. This inequality needs to be spoken about and addressed through global structural changes, and glossing it over with a simplistic, celebratory narrative helps (almost) no one.

God is a profitable and deadly business in Angola

Sometime after the end of the São Silvestre foot race through the streets of Luanda and the start of any of the many New Year’s Eve parties (this one, worthy of both Marilyn Monroe and De Beers, caught our attention), a tragedy occurred. Sixteen people died (among them three children) and one-hundred and twenty were injured at an event called “The Day of the End” at the Cidadela stadium in Luanda organized by the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (now global, it originated in Brazil and claims to have 8 million followers). According to the police, an estimated 250,000 people crowded into a stadium with a capacity of 70,000 where only two of the four gates were open. Early accounts reported people being trampled but hospital staff attributed mortality to suffocation, exhaustion and hunger (Novo Jornal No. 249, January 4, 2013).

Sometime after the end of the São Silvestre foot race through the streets of Luanda and the start of any of the many New Year’s Eve parties (this one, worthy of both Marilyn Monroe and De Beers, caught our attention), a tragedy occurred. Sixteen people died (among them three children) and one-hundred and twenty were injured at an event called “The Day of the End” at the Cidadela stadium in Luanda organized by the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (now global, it originated in Brazil and claims to have 8 million followers). According to the police, an estimated 250,000 people crowded into a stadium with a capacity of 70,000 where only two of the four gates were open. Early accounts reported people being trampled but hospital staff attributed mortality to suffocation, exhaustion and hunger (Novo Jornal No. 249, January 4, 2013).

The result of relentless publicity shilling (“The Day of the End: come bring an end to all the problems in your life – sickness, misery, unemployment, bankruptcy, separation, family arguments, witchcraft, desire”) capped by an exhortation to “Bring your whole family,” pastor Felner Batalha led his sheep to slaughter rather than salvation. UNITA representative Paulo Lukamba Gato has called for a revision of state policy on church groups. Human Rights activist and lawyer David Mendes thinks the church and pastor should be held responsible for the deaths. “They commercialized God,” he said. Nonetheless, most analyses in the local press agree that both church and pastor will come out of this none the poorer.

Despite a police report that places blame squarely on the church administration, Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos set up a Commission of Inquiry composed of six ministers and the governor of Luanda, reportedly a member of this church. The Angolan website Makangola thinks it’s hard to imagine that they will turn up anything the police did not. The church contacted the proper authorities prior to the event. Police, fire department, Red Cross and others were contracted and mobilized for security services outside the venue, but they assured the Ministry of the Interior that they would take care of security inside the stadium. Who then to blame when the bounty of their advertising, free transportation, and promises of the end of penury produced a surfeit of humanity?

IURD church in Alvalade

The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God spreads the prosperity gospel. Here’s one reading of how it works on U.S. shores. Wealth is a blessing for those who pray well. Those who tithe the church will prosper, says Edir Macedo, founder of the Universal Church. The bricks and mortar this church owns in key Luanda locations testifies to the fact that his church is prospering and operates with the Angolan state’s blessing. So isn’t this church/state relationship probably reciprocal? David Mendes calls it promiscuous. We’ll remind you of this image we’ve already posted. Different church, same idea.

In post-socialist, growth oriented Angola, where the rich are getting richer and the poor have only their faith, this is one very cruel and ironic example of David Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession.

January 14, 2013

France in Mali: the End of the Fairytale

Whew, Mali. French air raids against Islamist positions in Mali began Thursday night, and the dust hasn’t settled yet. The news is changing fast, but, three things emerge from the haze. First, fierce fighting in the North and the East, with French forces in the lead, will open up a whole new set of dangers. With Islamist forces on the attack, foreign intervention was necessary, and many Malians at home and abroad welcomed it enthusiastically. Still, this remains a dangerous moment all around. Second, while the latest crisis might not break the political deadlock in Bamako, it has already changed the dynamic. And third, despite the sorry state of mediation efforts to date—both within West Africa and beyond—savvy diplomacy is needed now more than ever.

Whew, Mali. French air raids against Islamist positions in Mali began Thursday night, and the dust hasn’t settled yet. The news is changing fast, but, three things emerge from the haze. First, fierce fighting in the North and the East, with French forces in the lead, will open up a whole new set of dangers. With Islamist forces on the attack, foreign intervention was necessary, and many Malians at home and abroad welcomed it enthusiastically. Still, this remains a dangerous moment all around. Second, while the latest crisis might not break the political deadlock in Bamako, it has already changed the dynamic. And third, despite the sorry state of mediation efforts to date—both within West Africa and beyond—savvy diplomacy is needed now more than ever.

First, the fighting. The French have come in hard and fast, with fighter jets flying sorties from southern France over Algerian airspace, helicopters coming in from bases in Burkina Faso, and special forces and Legionnaires from Côte d’Ivoire, Chad, Burkina, and France. There are indeed French boots on the ground, fighting alongside what remains of the Malian army and troops from neighboring countries. So far it is the air assault that has garnered headlines, chasing the allied Islamist fighters from the positions they had taken last week, as well as from most of their Sahelian strongholds (as I write, no reports of fighting in or around Timbuktu). Konna, Douentza, Gao, Léré, Kidal… : ça chauffe.

Three things on that.

The intervention was necessary. The drama of the Islamist offensive should not be underestimated—a successful assault on Sevaré would have meant the loss of the only airstrip in Mali capable of handling heavy cargo planes, apart from that in Bamako. The fall of Sevaré would in turn have made any future military operation a nightmare for West African or other friendly forces, and it would have chased tens of thousands of civilians from their homes. These would only have been the most immediate effects. After Sevaré, nothing would have stopped an Islamist advance on Segu and Bamako, although it is unclear to me that the Islamists would have any strategic interest in investing Mali’s sprawling and densely populated capital. Still, many Bamakois feared an attack, and had one occurred the human costs would have been astronomical. Malians remember well that only a few months ago, insurgent forces ejected the army from northern Mali as if they were throwing a drunk from a bar. Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal fell in a weekend. The army collapsed, and it has only been weakened by internal fighting since. Any other story is a fairytale.

The enemy is formidable. French officials expressed some surprise at the level of sophistication of the Islamist forces—well-armed, well-trained and experienced. In an early wave of the French intervention, one helicopter took heavy fire from small arms, and a pilot was killed; another French soldier remains missing. Malian casualties were heavy, and likely remain under-reported. Sources from Mopti refer to dozens of deaths among the Malian ranks, and there will be other casualties to come. In short, last week’s Islamist offensive put paid to the argument that the Malian army itself was capable of defending the country from further attack and of liberating the territory over which it had lost control.

This is not a neo-colonial offensive. The argument that it is might be comfortable and familiar, but it is bogus and ill-informed. France intervened following a direct request for help from Mali’s interim President, Dioncounda Traore. Most Malians celebrated the arrival of French troops, as Bruce Whitehouse and Fabien Offner have demonstrated. Every Malian I’ve talked to agrees with that sentiment. The high stakes and the strength of the enemy help to explain why the French intervention was so popular in a country that is proud of its independence and why the French tricolor is being waved in Bamako. That would have been unimaginable even 6 months ago—and probably even last week. More important than how quickly it went up will be how quickly it comes down; this popularity could be ephemeral. One tweeter figures French President François Hollande is more popular than Barack Obama right now. I’d wait for Hollande’s face to go up on a few barbershops before making that call, but the comparison gives a sense of the relief many felt when French forces came to the rescue of the Malian army.

Not everyone is in favor of the intervention. Let’s count some of the more vocal opponents—Oumar Mariko, Mali’s perpetual gadfly; French ex-Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin, who argues that it would be better to wait for the lions to lie down with the lambs; Paris-based Camerounian novelist Calixthe Beyala, plagiarist who argues that those Malians who would prefer not to live under a crude faux-Islamic vigilantism suffer from a plantation mentality; and some truly reprehensible protesters at the French embassy in London, who refuse to believe that most Malians are Muslims and don’t need religious instruction from Salafists. It’s hard to imagine a leakier ship of fools.

Second, fighting in the north has already changed the political dynamics on the ground in Bamako. The pro-junta movement MP-22 and Mariko, one of its most prominent leaders, opposed the French intervention just as they’ve violently opposed the possibility of ECOWAS help (this is the same crowd that nearly lynched the interim president last spring). Their position not only contrasts sharply with public sentiment, it also puts the movement at odds with Mali’s largest political coalition of the moment, the FDR, which had joined MP-22 in calling for a national conference in the days before the Islamist offensive. Since then the FDR has declared that now is not the time. What to make of this? First, as for MP-22, the dogs bark, but the caravan passes. Second and more importantly, although the question of the national conference might be bracketed for the moment, it will come back soon.

Three important changes have already occurred in Bamako:

First—and strikingly—even Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo, who led the coup in March and who still holds a great deal of political power, has welcomed the arrival of French troops. This is important: he had been forced to abandon the argument that his troops could go it alone. His fierce opposition to the idea that ECOWAS troops—still less French ones—would come to Mali’s aid had been only gradually been whittled down over the last several months, but it withered completely in the face of the recent Islamist offensive. Now, he has had to reverse course. When he made a lightning trip to Mopti-Sevaré over the weekend, it was hard to avoid the impression that he was struggling to remain relevant to both Kati (the garrison) and Kuluba (the presidential palace).

Second, virtually unremarked upon with all eyes in the East, several hundred French soldiers are deployed in Bamako to protect French citizens—of whom there are reportedly some 6,000 in Mali, of whom expatriates are a minority (press: please note). In the current emergency while the French troops are there ostensibly to protect their citizens and other civilians from terrorist attack, they implicitly secure the civilian government against its own military and against mobs like those ginned up by MP-22 and other radical associations. Meanwhile, soldiers from ECOWAS nations are arriving by the hundreds, although it is not yet clear what role they will play or where they will be stationed.

Third, their presence puts President Traore in a stronger position. In months past, both the junta and the anti-globalization Left have been allergic to the idea of any foreign troops in Bamako itself, and they have used violence and intimidation to secure their argument. Now Traore has proven strong enough both to ask for military aid and to receive it. Neither he nor his new Prime Minister Django Cissoko remains prisoner to the threats of the military or the radical opposition.

Still, especially given all that’s happened over the weekend, it is important to recall to that the political situation in Bamako remains unstable. Dioncounda Traore’s “interim” presidency is long past its constitutional sell-by date, and the rest of Mali’s political class—including its once-young angry Left—have hardly failed to notice that. Last week, before the offensive, a broad coalition formed to demand a “national consultation” (often bruited, sometimes scheduled, never held), Traore’s resignation (to be replaced by whom?), and the launching of a military campaign to retake the north (which, coincidentally, they got, even if it was not the Malian-led initiative they wanted). On Wednesday demonstrators burned tires, blocked traffic, and shut down two of the three bridges across the Niger. Some men in masks reportedly fired guns in the air and carjacked trucks and 4X4s. In response, Traore closed all schools in Bamako and in the garrison town of Kati. If he was attempting to keep the students from joining the fray, he failed. In addition to opening Traore up to a certain amount of Twitter ridicule (Twittercule?), Traore’s edict brought the students’ union out on the streets on Thursday. They broke into high schools, chasing out students who were sitting exams (bad luck: apparently the questions were easy). At the moment, schools are open again, but the President has declared a state of emergency. In short, Bamako remains uneasy, and the “sacred union” of the last few days can only be temporary.

Third, what all this suggests is that the Mali crisis—which long ago became the Sahel crisis—needs diplomatic intervention every bit as urgently as it needed military intervention.

To date, West African meditation efforts have been manipulated by Burkinabe President Blaise Campaoré, whom ECOWAS has dubbed its mediator in the conflict. Few Malians take Campaoré as a legitimate interlocutor, and no one believes that he has the country’s interests at heart. After profiting from hostage-taking by negotiating ransoms with AQMI, Campaoré was until recently harboring dozens of MNLA fighters while attempting to manipulate ex-Prime Minister Cheikh Modibo Diarra by remote control. The military threw Diarra out of office in December, and a steady campaign to tarnish his image irreparably has accelerated since then, as he stands accused of diverting funds intended to aid the refugees to finance his political party. As for Campaoré’s guests from the MNLA, it’s said that he asked them to leave Burkina after they refused to keep a low profile. Several dozen have since turned up in Mauritania. In response to the latest round of skirmishing, which compelled the postponement of further negotiations in Ouagadougou, Campaoré’s lead diplomat Djibril Bassolé called on both sides to stop firing and hold their positions, as if this was a legitimate request to make of a national army defending its own territory and civilians, and as if he himself had anything better to offer than the prospect of further degrading the situation.

As for the UN, although after much discussion the Security Council has authorized the use of force by ECOWAS to re-establish Mali’s territorial integrity, the organization’s Secretary General seems to be running, as ever, on empty. Ban Ki-moon named Romano Prodi his emissary for the Sahelian crisis, leaving some to wonder if he had not got his dossiers shuffled. Prodi, a former Prime Minister of Italy, knows nothing of the Sahel and speaks none of its languages, only stumbling along in French. He is scarcely qualified for the job: in 2008, he led a UN-African Union panel on peacekeeping. More to the point, perhaps, he once helped to negotiate for the release of hostages held by the Taliban in Afghanistan. Yet the narrow lens of the hostage conundrum is precisely the wrong way to examine the Sahelian crisis (see: Nicolas Sarkozy), and this is not a peacekeeping scenario. At an event in Paris back in June, Manthia Diawara made the very good point that if Mali’s friends and neighbors take the country’s crisis seriously, they ought to be delegating some serious mediators to it. Campaoré and Bassolé, on behalf of ECOWAS, and Prodi, on the part of the UN, don’t make the grade. Could Presidents Yaya Boni of Benin or Macky Sall of Senegal, for instance, step in where Campaoré has failed? Africa is not short on diplomats, elders, and people of experience. President Traore—and Secretary-General Moon—should be writing to them as well.

Disclaimers:

The situation is changing very quickly, and much of what is written here may soon be outdated.

For lack of a better term, I use “Islamist” to refer to the alliance of AQMI, Ansar Dine, MUJAO, and other foreign movements. Other terms are inadequate (“terrorist”) or inaccurate. I reserve the terms rebels or insurgents for the host of anti-government forces, which includes the MNLA, a movement now at odds with its former allies Ansar Dine.

More on the medium / long-term stakes of foreign intervention in another post…

Discovery Channel’s Africa

The Discovery Channel and the BBC have joined forces to produce a new seven part series entitled, Africa. The series is four years in the making and brings together stunning footage of the landscapes and animals within the continent. The first episode focuses on the Kalahari Desert, while later ones will capture the wildlife in others regions spread throughout Southern, Central, Eastern and Northern Africa, with later episodes titled (you’ve guessed it), “the Congo”, “the Cape” and “the Sahara.”

The narrative style of the series is both informal and informative. The series is narrated by Sir David Attenborough, who is a kind of institution in this kind of programming. Attenborough provides a laid back voice as he projects the thoughts of the animals. For example, when he narrates the leopard contemplating a warthog for lunch, it’s a “bad idea,” and then the camera pans to the leopard looking for an easier target for its lunch. The soundtrack and narration allow us to identify more easily with the film, and both instill tension, wonder, and relief in the small triumphs and battles played out among the animals. Though most of the drama created between animal encounters is welcome, it is sometimes overwrought (already some viewers have accused the show of manipulating them), as demonstrated with this line, “In the Kalahari, you have to take your food wherever you can get it, even if that means becoming a cannibal.” (This was regarding armored crickets eating an injured fellow.) The statement makes it seem that insects devouring each other is more pronounced here than in any other environment, which isn’t so.

Even while the series seeks to make you feel as if you are becoming more intimately connected to the wild, it also tries to create a distance, invoke an alienness and instill an ancientness to the region. This tactic is perhaps best borne out in the intro to the series. The logo AFRICA flashes across a globe in what looks like the start of a movie trailer about an otherworldly encounter. In the first episode, “the Kalahari,” Attenborough describes the mountains and deep valleys surrounding the desert as, “land buckled and scarred by a volcano,” that boasts the “oldest piece of crust on the planet.” Or when it comes to the underground fossil aquifer, caves, and the fish that swim beneath the desert, it all “may sound like science fiction.” The film even ventures into “local myth” to describe the phenomenon behind what are termed “fairy circles” before providing us with the scientists’ best guesses, which are still just guesses.

But plying potential audiences with expansive vistas, mystery, exotic landscapes, and ancient holdovers is what seems to be the time worn formula when presenting Western audiences with most things African. It will be very interesting to see what Discovery and the BBC do with the last two episodes, the “Making Of Africa” and one that will tackle the future of Africa’s wildlife. As, in their words, “the greatest and most iconic wildlife continent is at a tipping point. The animals of the next generation will face very different challenges than the ones met by their ancestors—and the animals themselves must adapt to the new landscape and changing relationship with humans.” Despite this description seemingly able to apply to the entire world, the series creators seem most eager to save the animals of Africa. But perhaps this is most natural, I’m sure their jobs depend on it.

The (Kenyan) Male Gaze

Levi-Strauss writes of a Native American people for whom every dream has a hidden sexual meaning, except explicitly sexual dreams, for which it is imperative that non-sexual interpretations be found. I am reaching for an Oscar Wilde aphorism here. Everything is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power. The Freudian in me demurs against this pan-sexualization of everything, and even more against reducing sex to power. But the feminist in me tarries at this sex:power locus, because it is where patriarchy inheres, turning sex into a zero sum conquest with winners and losers. The sexual terrain becomes stark, arduous. One must guard against being had. Against becoming just another notch in another belt.

Levi-Strauss writes of a Native American people for whom every dream has a hidden sexual meaning, except explicitly sexual dreams, for which it is imperative that non-sexual interpretations be found. I am reaching for an Oscar Wilde aphorism here. Everything is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power. The Freudian in me demurs against this pan-sexualization of everything, and even more against reducing sex to power. But the feminist in me tarries at this sex:power locus, because it is where patriarchy inheres, turning sex into a zero sum conquest with winners and losers. The sexual terrain becomes stark, arduous. One must guard against being had. Against becoming just another notch in another belt.

A friend recently alerted me to the #TeamMafisi hashtag on Twitter. Mafisi is Swahili for hyenas. Armed with the banality of Twitter hashtagging, this “team” of mostly young Kenyan men directs its violent gaze on women’s bodies—their prey.

In her email, my friend wrote:

They disgust me. It’s one thing to objectify women. But that’s not enough for them; they go on to body shame, to call women ugly, to declare entitlement to a woman’s vagina (because a woman has nothing else to her name except a vagina). And of course, women are referred to, richly, as bitches.

Like most violence, misogyny deploys shock and awe to confound our responses beyond coherence. I felt like I did not know how to begin this post. I feel like I have very little to say. Mostly I feel angry.

Although the misogyny on #TeamMafisi might seem reflexive, it is not. Rather, it is so deliberate and organized that it has defenders within the Kenyan blogosphere who lay out its codes of conduct and memos. One could even say—to borrow from blogger (and English professor) Keguro—that the misogyny here is banal. The banality, say, of tweeting and hashtagging, is part of the socio-historical through which misogyny becomes reflexive. Banality becomes the training we put ourselves through to make misogyny reflexive. What might it mean to understand misogyny through the kind of training that produces reflexes? Certainly the banality of tweeting and hashtagging labors to traffic the misogyny of #TeamMafisi and pass it off as ordinary, everyday, as part of the affects and intensities exchanged through the internet, and therefore something one must put up with. The fallacy is that misogyny is slightly inconveniencing.

As Western media deploys an Orientalist lens that locates rape and misogyny squarely in India—meaning, in the Global South, outside the West, and, yet again, as the need to save brown women from brown men—I would like us to think locally. Misogyny is not just a problem in India; in Kenya; or on Twitter. It is a problem everywhere, including here in the West from where I write.

* The image is taken from artist Wangechi Mutu’s work.

Is Chester Missing blackface?

He performs to packed-out theatres and is a regular correspondent on a satirical television news show, Late Nite News with Loyiso Gola (LNN) on South African private TV channel, Etv. He’s at times raucously funny and almost always on point. He writes, he tweets and he tjunes white okes (for the non-South Africans: he gives it straight to whites) things like: “All white South Africans have benefited from apartheid. If you try to go ‘except me’, then I am saying it to you especially.” Chester Missing is his name and he is a racially ambiguous black guy (more on that in a bit) who uses satire to chime in on race, privilege, and other thorny political and social issues in South Africa. This has seen him rise to become the country’s “hottest new political analyst”, according to his tongue-in-cheek, self-aggrandizing bio. Standing next to him, moving his hands and mouth and giving him voice, is a white guy, Conrad Koch, a puppeteer ventriloquist and comedian.

For those unfamiliar with him (and if you haven’t figured), Chester Missing is a puppet. He is a front, a mask and, in part, a caricature. When talking race and apartheid, which he does frequently, he is an appropriation of black South Africans’ thoughts, frustrations and eye-rolling (at whites) since Apartheid’s legal and political mechanisms were dismantled 19 years ago. And as Missing’s popularity has risen, so has Koch’s, which begs the question: is Chester Missing blackface?

A good place to start would be placing Missing’s race. Until earlier this month, it was apparent to all that he is “of colour” in the sense that he is in all likelihood coloured (the South African word referring to those of mixed race) or he might be black. Financial Mail journalist Hilary Toffoli, for example, described the puppet as a “coloured cynic” and reviewers of his show ‘The Puppet Asylum’, which ran in February 2012 at The Baxter Theatre in Cape Town, took it for granted that he was coloured. What is for sure is that audiences everywhere understood that Chester Missing was not white. But earlier this month, after Koch (and Missing) were harangued for most of the week by tweets claiming, among other things, that the performance was blackface, Koch’s and Missing’s Twitter accounts disavowed the puppet’s racial identity.

“I am Chester Missing, SA’s top political analyst PUPPET. I am not of colour/black/Indian/Mayan or coloured. My puppeteer is a white,” the tweet read.

But before the furore, Koch had in interviews described the puppet as “a nonracial guy who’s of colour” or “coloured.” He’d also suggested that the ambiguity was intentional, as it allowed him to use the puppet to speak with the in-group voice of the spectrum of the South Africa’s black identities. In performances, Koch also often pulls back the veil and alludes to the possibility that this could be blackface, although not in so many words.

Koch said in an interview with the South African web publication, The Daily Maverick: “I’m a white guy using a black guy to get somewhere, literally. In my one-man show [Chester] literally says, ‘You just use the black puppet because no one wants to laugh at a lame-ass, unfunny white guy.’ It’s true.”

In addition to being a puppeteer, ventriloquist and comedian, Koch is also a social anthropologist. So even though he may have Missing make the remark for its comedic value, he surely must appreciate the kernel of truth behind it.

The curious attempt earlier this month to make the puppet completely raceless is perhaps a manifestation of Koch’s anxiety, discomfort and, I suppose, frustration at how his performance with Missing is steeped in and operating from within the context of puppetry’s history in Western culture (from which puppetry in South Africa draws heavy influence) as a tool to create and propagate grotesque racial stereotypes about black people.

I myself have a 'coloured' puppet. I am very conscious of Spike Lee's movie 'Bamboozled' in this. I hope that the mix I go 4 is justified.—

Conrad Koch (@conradkoch) January 04, 2013

@MrPhamodi @chestermissing Just saw your tweet. I have had huge anxiety re the blackface issue. Not entirely in disagreement with my critics—

Conrad Koch (@conradkoch) January 04, 2013

Perhaps calling what Koch does with Missing blackface could be seen as harsh or misguided because, firstly, Koch has a repertoire of other characters and his stock-in-trade is appropriating voices and appearances. Secondly, blackface began as white racism’s gross misrepresentation of black bodies, mannerisms and intelligence. Not only was it untrue, it exploited and reinforced the mechanisms that denied black people rights, particularly ownership of how they were publicly portrayed and understood. Missing isn’t a product of white racism, at least not directly, nor was he created with the intention to reinforce it. He often challenges it and what it has produced, and is spot on when he does so.

In one of his columns, he tears into apartheid’s last president, FW de Klerk, and his newfound popularity among the international media (this means you, CNN and BBC) as a moral voice of sorts on the current state of South Africa.

“I would be fine with de Klerk keeping the (Nobel Peace) prize, except now he’s telling us what he thinks. Turns out he really is a bald, brainless bigot,” Missing wrote after de Klerk’s disgraceful interview with Christian Amanpour in May 2012.

He went on CNN and told the world that black people “were not disenfranchised” by the homeland vibes. Madness! What’s next? Nazis telling us about how the Holocaust was only bad for the really thin people (with respect to Jewish ous)?

But if you scratch deeper some contradictions begin to emerge. Chester Missing is by far Koch’s most popular character and Koch recognises that this in large part is due to dressing up his views as a liberal white guy in a funny black character. Whites generally don’t take kindly to another white person saying the things Missing does, and it’s unlikely that they’d pay to hear it. And blacks, among whom Missing and LNN are most popular, would rightly tell him, “Koch, we know all these things you’re telling us. Go tell this to the other white okes.”

Koch admitted in a recent interview on Johannesburg’s Radio 702 that Missing goes where he himself, as a white guy, feels afraid or is reticent to go. So whereas blackface mollified the white conscience by reinforcing concept of white supremacy, Missing, using the sleight of hand of puppetry, leaves the white conscience unflustered by hiding dissent amid the ranks behind a black face. Either way they both allow for a similar result: inaction or obliviousness on the part of whites to racial injustice created for and by whites.

If Koch wanted to be interesting, funny and advance the recognition of racial injustice at the same time, which he’s said he does, he should probably have a puppet modeled after himself: an irreverent, young white man with a rapier wit and a surprisingly refreshing take on race relations in South Africa. There are too few like him with access to a public stage.

I expect the typical response to this would be that Koch should be left alone to do comedy the way he sees fit. However, Missing’s race was an intentional choice made with both a comedic and a social objective. And race being so sensitive topic in this country has made it a such key weapon in Koch’s lampooning that it’s impossible for the socially aware to laugh vacuously at the puppet’s jokes without interrogating the assumptions underlying the performance. At the very least Chester Missing is an embodiment of the fear, unwillingness or inability of liberal-minded whites to use their own voices, faces and words to talk publicly about this country’s racialised privilege. That’s quite a burden to place on the tiny shoulders of Chester Missing.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers