Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 501

January 18, 2013

Papa Ghana’s tribute to Amsterdam

For those planning to visit Amsterdam anytime soon, there is no need for a Lonely Planet guide. Just have a listen to Papa Ghana’s new track ‘Damsco’ (slang for ‘Amsterdam’) which he just released. In case you don’t speak any Dutch (slang): the ‘Damsco’ lyrics read as an ode to the city. The track starts off with Papa Ghana paying his respect to the city’s biggest folk singers, but soon goes on to sum up what’s typical for ‘Damsco’: fare beating in the tram, hipsters in the ‘negen straatjes’ (‘nine streets’, a hip — yes — part of town), an arrogant attitude displayed by “Amsterdammers” (according to the rest of the country), and of course football club Ajax.

Papa Ghana, whose real name is Jefferson Osei, is a rather interesting new name in the Dutch Hip-Hop scene. Just last year, the member of L’Afrique Som Systeme collective released his first EP called ‘Mandingo’ featuring his single ‘I’m an African’.

He calls his music, which one would describe as dub and electro, as ‘diaspora beat’. “It’s a mix of all kinds of music genres…[It is] something I named myself, because it is music from different cultures all mixed into one,” Papa Ghana explained to me last year in an interview for RNW’s programme Bridges with Africa. Per usual, any musician who claims to have ‘invented’ a new genre, I’d take with a grain of salt. But on ‘Damsco’ Papa Ghana proves that he at least represents the second-generation immigrants — the slang is largely based on Sranangtogo (the Surinamese language) and he even raps in Arabic on a track. What I love about those songs is how he uses present-day urban culture and slang to pay tribute to the more ‘traditional’ culture of the city.

And like any self-respecting rapper these days, Papa Ghana also has his own clothing line called ‘Daily Paper Clothing’.

Race politics in Ghana

Jemima Pierre, professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt University, has written an ambitious book in The Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race (University of Chicago Press 2012). She engages Ghanaian and African diasporan constructions, perceptions, and performances of Blackness and Whiteness in contemporary Ghana. By doing so, she brings anthropology into an ongoing conversation on race within African studies dominated largely by historians and South Africanists from a variety of specializations. The book, she says in her preface, is an “ethnography of racialization that insists on shifting the ways we think about Africa and the history of modern identity” (xv). She argues that the process of racialization within the framework of global white supremacy links continental Africans and people of African descent in the diaspora. Race matters, to Pierre, and she culls ethnographic material from her two decades of research in Ghana that belies its irrelevance in every day urban Ghana.

Jemima Pierre, professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt University, has written an ambitious book in The Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race (University of Chicago Press 2012). She engages Ghanaian and African diasporan constructions, perceptions, and performances of Blackness and Whiteness in contemporary Ghana. By doing so, she brings anthropology into an ongoing conversation on race within African studies dominated largely by historians and South Africanists from a variety of specializations. The book, she says in her preface, is an “ethnography of racialization that insists on shifting the ways we think about Africa and the history of modern identity” (xv). She argues that the process of racialization within the framework of global white supremacy links continental Africans and people of African descent in the diaspora. Race matters, to Pierre, and she culls ethnographic material from her two decades of research in Ghana that belies its irrelevance in every day urban Ghana.

She was inspired to write this book, Pierre tells us, by the failure of African and African diaspora studies scholars to “fully appreciate the sociohistorical reality of Black identity formation on the African continent and its articulations with global notions of Blackness” (222). Actually, there is a wealth of impressive scholarship that directly or indirectly addresses race and related issues in Africa. More on this below. Still, Pierre’s observations provide a rich and textured documentation of the meanings and expressions of blackness—and, ultimately “Whiteness”—in early 21st century Ghana. The predicament, she suggests is that Whiteness serves as a reference point for Ghanaians’ notions of beauty, Blackness, and power, but Ghanaians remain blind to this and the framework of global white supremacy that has contributed to the social and political structure of their society.

As a historian of Africa I found Pierre’s effort to provide an alternative to the romantic readings of Ghana’s late colonial and early independence periods particularly noteworthy. In the chapter “Seek Ye First the Political Kingdom” Pierre argues, in short, that the nationalists, Nkrumah among them, failed to dismantle the racialized structures of imperialism. Rather than revolutionary or dramatic change they settled for safeguarding their positions of power. “Nkrumah and his political party, the CPP,” writes Pierre, “made compromises that reflected the contradictory nature, and compromised position, of a nonrevolutionary transition mediated by and through the terms of the former colonial master” (48). She strips some of the veneer from Nkrumah’s pan-Africanist, revolutionary façade and describes decolonization as more politically and culturally conservative than radical. The ruling Convention People’s Party, she rightly states, spent more time consolidating power than uprooting the remains of the colonial system. This is not merely history, she suggests, because the consequences of these choices had implications for present-day Ghana. While not necessarily original—she does not claim that it is—this is a wonderful point of departure to revisit Ghana’s nationalist period.

Pierre is strongest with her interpretation of her interviews on discreet issues, which expose individuals’ or small groups’ unconscious racial reading of a practice or people. Throughout chapter four, to offer one example, she unpacks skin bleaching and associated ideals of beauty among those who do and do not practice it. Skin bleaching, she explains, “actually reveal common ideas about the transnational significance of race” (103). This discussion and a brief etymology of “mi oburoni”—my white/light person—as a term of endearment demonstrates the degree to which the Ghanaians Pierre came into contact with imbibed whiteness and/or light skin as preferable to the darker skin of most Ghanaians.

As a work of anthropology this book captures a slice of Ghanaian views within a specific historical moment. But the slices will look different as we move away from the coast to explore how urbanites in the interior cities of Kumasi and Tamale conceive of the intersection of blackness, beauty, and power. I suggest that a broader geographical and historical framework would complement Pierre’s ethnographic analysis and align her study more closely with its aspiration to document racialization in urban Ghana. This would include accounting for the diversity of African responses to the European imposition of a racialized power structure. For example, along the coast from the closing decades of the nineteenth century through World War II, the so-called colonial African elite in Accra and Cape Coast vigorously debated the meaning of race and the colonial state’s racist practices. Indeed, colonial era Africa-run newspapers are replete with African critiques of racism and colonial rule in general.

Pierre’s neglect of this history leads her to overstate the power that Europeans exercised. Outside of urban areas, where far fewer Africans lived, until the closing decade of British rule colonial administrators had mixed success in their efforts to assert control over the Africans that they counted as colonial subjects. Moreover, the chiefs through whom administrators sought to incorporate local societies within the empire were frequently overthrown, undermined, and/or ignored by their so-called subjects. In short, local individuals and groups under colonial rule exercised far more control over how they defined themselves and their political environment than such terms as colonial rule, white supremacy, and subject imply. It is important that we do not silence the agency that Africans—commoners, royals, and employees of the colonial state—exercised in day-to-day affairs lest we foreclose on the possible meanings of racialized power and its limits.

My reading of Pierre’s book prompted me to imagine new directions for thinking about blackness, difference, and power in Ghana. Without a doubt, racialization on its coast bares both the silent and more palpable imprints of “Whiteness” and the legacies of European colonial rule. However, there is a different picture in the country’s north. Northerners commonly speak of the lighter brown skin of many Fulani as attractive for reasons not related to colonialism or white supremacy. Considering the differing north-south dynamic in Ghana and elsewhere on the continent calls upon us to explore how we might push beyond privileging the coast and Europeans to frame our understanding of Ghanaian and West African conceptions of race, power, beauty, and Blackness. To what extent does northern Ghana’s more Sahelian cultural and political orientation offer a counter or alternative paradigm for the West’s imprint on the coast?

Pierre is the exception among anthropologists in forcefully tackling a comprehensive study of race in Ghana. As more anthropologists follow her lead, the rich historical scholarship on race—in its myriad iterations—in Africa will enliven their work. One example is A Different Shade of Colonialism, in which Eve Trout Powell masterfully illuminates the confluence of European and Egyptian colonial projects in Sudan and the consequences for Sudanese articulations of power, ethnicity and racial difference. In Past Times and Politics by Laura Faire, local conceptions of race, particularly blackness, define the social status of the enslaved and their descendants in Zanzibari society. In a less direct, but still noteworthy manner, in Native Sons Greg Mann unpacks the intersection of conceptions of race, citizenship, and nation in post-World War II Mali. Most recently, Jonathan Glassman’s magisterial War of Words, War of Stones: Racial Thought and Colonial Violence in Colonial Zanzibar centers African and Indian Ocean derived meanings of race and racial difference for understanding relations among individual and groups of Africans on the Swahili Coast during the European colonial period. These are mere samples from a dynamic body of scholarship.

Notwithstanding its limited historical and cultural context and geographic scope, Jemima Pierre’s book is a welcome addition to an important field within African and African diaspora studies. It sheds new and important light on the contours and limits of European imperial power in Africa, and demonstrates the challenges of upholding social categories in a forever and rapidly changing social and political environment. Most important, Pierre helps deepen our understanding of confluence of race and power as a global phenomenon.

* Ben Talton is an associate professor of history at Temple University in Philadelphia.

When Wikipedia gets to write Malawi’s national history

By Jimmy Kainja

By Jimmy Kainja

Malawians yesterday staged popular demonstrations against egregious rises in the cost of living brought about by the economic reforms made by President Joyce Banda, under orders from the International Monetary Fund. If the spirit of popular protest is alive and well today, it’s no thanks to The Daily Times newspaper, who earlier this week ran an “article” purporting to commemorate Malawi’s first great anti-colonial hero that they’d lifted word for word from Wikipedia.

Every January 15, Malawi celebrates John Chilembwe Day and remembers the life of Reverend Chilembwe, the first and perhaps the most revered of all the Malawian freedom fighters. Western-educated, Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland (now Malawi) around 1900, after 7 years studying theology in the United States, where he is believed to have encountered the works of black thinkers such as Booker T Washington, advocating black empowerment and pan-Africanism.

On his return, Chilembwe was frustrated by colonial racism and he objected to the British government’s order that the Nyasas should go to Tanganyika (now Tanzania) and fight in the First World War against the Germans. His frustrations forced him into an unsuccessful rebellion that came to be known as the Chilembwe Uprising, soon after which he is thought to have died on February 3 1915, as he fled into Mozambique. His burial site is unknown and there is no consensus among historians whether he was indeed killed or simply disappeared.

However, it is his bravery and love for his people that has made him a martyr and a national hero. Everyone learns about him at school and until last year his face was on all Malawian banknotes. Only the 500 Kwacha note (pictured above) now bears his face; other historical figures have been added on the rest of the banknotes, such as Rose Chibambo, a hero of the independence struggle and Malawi’s first cabinet minister.

Newspapers have always carried supplements about Chilembwe’s life for Chilembwe Day — his achievements, vision and whatever lessons media organisations think Malawians can learn from his life. This year was no exception, but it was the first time in nearly ten years that I have read the supplements, as I had always been out of the country during this period.

Malawi has only two daily newspapers: The Nation and The Daily Times. I only bought the latter. It had 24 supplementary pages on the subject — an impressive amount of space that was not matched by the breadth of the articles. The content could have been much better.

What caught my eye, however, was an article solemnly entitled: “Important facts about John Chilembwe”. I noticed that this article had no by-line, so I checked at the bottom, where it was indicated that the entire article had been copy-pasted from John Chilembwe’s Wikipedia entry.

The Daily Times has just published a Wikipedia entry? I felt something was wrong, not only because I found it irresponsible to relegate a national history, the story of a national hero, to Wikipedia, but also because I know The Daily Times has a lot of capable journalists who could have done a better job. If not, could the newspaper not ask one of the many distinguished Malawian historians to write on Chilembwe?

This had lack of seriousness painted all over it. Why did The Daily Times not prepare properly for Chilembwe Day? I am aware that Wikipedia is free and that a lack of editorial resources could have forced the decision. Yet I still find it insulting to the national intelligence. Have we stooped so low that we are relying on Wikipedia to give us “facts” about our national heroes? I thought “facts” ought to be verifiable? How do you verify Wikipedia entries that have faceless authors and editors whose expertise is unknown? Shouldn’t we expect more from a national newspaper?

* Jimmy Kainja is a media scholar, writer, social and political analyst. He is interested in political and social change in Sub-Saharan Africa, Malawi in particular. He blogs at Spirit of uMunthu and appeared on our list of Malawi’s Top Tweeters (follow him on twitter @jkainja).

January 17, 2013

African Lookbook: Fashion and Oral Interviews Go Together

I first met Aaron Kohn, one of the co-founders of African Lookbook, a site that combines a one-stop online fashion store with oral interviews, earlier this summer at a New York University sponsored conference on Distance and Desires: Encounters with the African Archive. Sometime during the afternoon session on “the end of the colonial gaze,” we sneaked out and got talking about their site (Aaron has a partner at African Lookbook, oral historian Phil Sandick) and I quickly learned about the trove of oral interviews they’ve already done with artists and curators; sample: photographer David Goldblatt, musician Seun Kuti, Joost Bosland (of the South African Stevenson Gallery), writer Abdi Latif Ega, etcetera. On African Lookbook, they described the partnership thus: “Our interviews are primary sources: raw, academic in nature, and uneditorialized. For our shop, we work with people around the world to help us find cutting edge African products.” While I was still curious (more baffled) about the connection between fashion and oral interviews, we agreed that Africa is a Country would form a partnership with them.

I first met Aaron Kohn, one of the co-founders of African Lookbook, a site that combines a one-stop online fashion store with oral interviews, earlier this summer at a New York University sponsored conference on Distance and Desires: Encounters with the African Archive. Sometime during the afternoon session on “the end of the colonial gaze,” we sneaked out and got talking about their site (Aaron has a partner at African Lookbook, oral historian Phil Sandick) and I quickly learned about the trove of oral interviews they’ve already done with artists and curators; sample: photographer David Goldblatt, musician Seun Kuti, Joost Bosland (of the South African Stevenson Gallery), writer Abdi Latif Ega, etcetera. On African Lookbook, they described the partnership thus: “Our interviews are primary sources: raw, academic in nature, and uneditorialized. For our shop, we work with people around the world to help us find cutting edge African products.” While I was still curious (more baffled) about the connection between fashion and oral interviews, we agreed that Africa is a Country would form a partnership with them.

We’d publish short interpretive posts once a week at the same time as the interviews go live. The first post will be on the David Goldblatt interview. We will post Neelika’s take on the interview along with a link back to the transcript on African Lookbook’s site tomorrow. But before we get to that, I sent some questions to Aaron and Phil about African Lookbook.

Some people may find it hard, at first, to make the connection, or any connection, between a one-stop online fashion store and oral interviews; is the goal at best some kind of informed consumption? Can you clarify the connection and why that connection matters? What are problems and benefits presented by this union?

Some people may find it hard, at first, to make the connection, or any connection, between a one-stop online fashion store and oral interviews; is the goal at best some kind of informed consumption? Can you clarify the connection and why that connection matters? What are problems and benefits presented by this union?

When we set out to create a body of primary sources related to African creativity, we realized people couldn’t actually interact with much of what interviewees were discussing. So we decided to carry the products too. Kinda like when one views an exhibition in a museum and then has the opportunity to buy a poster, a print, a book, a keychain, etc. Do people find it hard to make the connection between a museum and its shop? The goal is to sell stuff we think is really great on both a theoretical level and a design level. And most of the products are new to the US market. We’re helping provide an entry for African designers and manufacturers.

The need to sell stuff results from the fact that oral history interviews are a substantial investment of time and money. There’s research preparation, scheduling, pre-interview meeting(s), setup, interview, transcription, transcript checking, back-and-forth with the interviewee through the transcript finalization process (which we hope is minimal), formatting, indexing, and publication.

So “informed consumption” is one way of putting the marriage of shop and archive. In terms of distributing these goods, we know we can do it in good, transparent ways, and tell the products’ stories over time. We want to distribute solid stuff that people can enjoy so that we can fund our research archive. Those are the connections and benefits.

As for problems, one could say there are significant complications arising from this for-profit relationship with a research archive. But, as Foucauldians, we don’t believe the complications are any more or less significant than those arising out of even the most “objective” academic research. We let sales fund our research, but we don’t let sales guide it.

What templates / sites would you say you closely resemble African Lookbook?

What templates / sites would you say you closely resemble African Lookbook?

On the retail side, we’re Fab.com meets the MoMA Store store meets granola fair trade meets (we sincerely hope) critical theory gifts. On the oral history side, we’re Columbia Center for Oral History meets the ACT UP Oral History Project meets Juxtapoz.

How different are you from “philanthropic fashion” associated with Suzy Menkes, Diesel Jeans’ owner and Bono’s wife, Ali Hewson? Or what enterprises like Monocle do?

How different are you from “philanthropic fashion” associated with Suzy Menkes, Diesel Jeans’ owner and Bono’s wife, Ali Hewson? Or what enterprises like Monocle do?

We’d have to see a label from the Diesel+EDUN collection. If there are Mbembe and Comaroff quotes on it, then maybe we’re not that different. Many of the artists behind the products in our shop don’t want to be seen as “African”. We explore these subjectivities in some of our oral histories. They want their sweaters in department stores because they exemplify good fashion design. There’s no reason good fashion can’t also be “good business” for African workers, African cotton, etc. On the other hand, some of our products are fair trade and/or buy-one give-one, but we carry them because we like the product.

How does one make money from oral interviews?

Everyone interviewed in our oral histories has chosen to be involved because they understand the importance of creating primary sources on African creativity. We don’t intend to make any money off of these narratives; that’s why we have a shop. Most oral history archives are institutionally based and/or funded (and usually at universities). We don’t have an institution financially backing us, so we’re trying a different model that we think could work: we sell stuff that, if you like, is informed by the interviews, and the proceeds from those sales fund more interviews, which support more products.

Can you tell us about the kinds of people you have interviewed and who you still have lined up? With few exceptions, the majority of interview subjects are South African btw, will that change? What can we learn from these interviews that we won’t find elsewhere?

Can you tell us about the kinds of people you have interviewed and who you still have lined up? With few exceptions, the majority of interview subjects are South African btw, will that change? What can we learn from these interviews that we won’t find elsewhere?

We’ve interviewed musicians, writers, gallery directors, academic department heads, photographers, sculptors, designers, museum curators, and art critics. We’ve got more of the same plus festival directors, painters, architects, film directors, and political scientists lined up. We have a growing list of hundreds individuals, African and non-African, whom we’d like to interview. Everytime we see someone who we think we add something to the archive, we put them on the list.

There are multiple things that can be learned from these interviews. First, you can learn how an artist tells a particular story on a particular day to a particular person. (After all, that story would be different were it told to, say, the narrator’s mother.) You can learn how the person strings together memories into a narrative, thereby creating meaning to pass along to the listener. You can learn the facts as the narrator tells them. You can hear silences when certain events aren’t mentioned, informing you that this narrator prefers–for whatever reason–to skip events and elide them out of his or her autobiographical narrative. The point is that we give as raw of a version of the conversation as possible in order to facilitate interrogation through the lens of whatever research question or general curiosity the reader might have.

Most of the interviews are South/Southern Africa focused because we started African Lookbook while Aaron was living in Jo’burg, and Phil lived in Botswana for three years before that. It’s where we had the most connections, and it was the easiest for Aaron to interview. We’re now in New York and Chicago, so there will be more US-based interviews, and people have joined from across Africa to help collect other interviews. Future interviewees will be from all over.

You’ve written somewhere that the aim with the oral interviews is to create “a body of primary sources that explores the ways Africans are being represented and are moderating their own identities around the world”? What does that mean?

You’ve written somewhere that the aim with the oral interviews is to create “a body of primary sources that explores the ways Africans are being represented and are moderating their own identities around the world”? What does that mean?

Olu Oguibe, in his The Culture Game, raised concerns about how African artists were being subjected to invidious interview techniques. Zoe Strother demonstrated that collecting primary sources in Africa is a contentious (postcolonial) issue. Oral Histories, though not perfect, help to solve some of the problems formerly addressed by the two.

The goal of oral history is to provide a “protected space,” as Mary Marshall and Dori Laub put it, in which people can tell their own stories. While this view has traditionally been associated with trauma interviews, Phil’s opinion is that most life events are traumatic in some form, so we try to create that space for each interviewee. We then publish their stories as they have told them to us. We don’t edit the language in the transcript. The interviewee may do so, but it is discouraged and generally does not happen to any significant degree. So rather than have one’s stories told by others, be it by Fox News or by NKA, narrators tell their own stories and that’s what we publish. We are lucky that technology has advanced to the point that the Internet publication of a complete transcript incurs zero marginal cost.

We, too, will write about ideas that emerge through the interviews, since we agree with Alessandro Portelli that the responsibility of those who gather testimony is to write about it and be affected by it. Personally, our research interests are more aligned with deconstructivist analysis of intersubjectivity than positivist collection of evidence.

You’ve acknowledged that oral interviews are fraught with “theoretical … (and) practical” issues. Can you tell us about some of the challenges of doing these kinds of oral interviews?

You’ve acknowledged that oral interviews are fraught with “theoretical … (and) practical” issues. Can you tell us about some of the challenges of doing these kinds of oral interviews?

On the practical side, and this gets at your South Africa comment above, many of our interviews have to be done over Skype. This is dreadful for oral history interviews, where you’re trying to say as little as possible but reinforce via other modalities that you are attentively listening. So our first batch were all done in person, which meant they took place where Aaron was–in South Africa. Setting up a time for interviews across time zones can be difficult, inconsistent internet connections can be frustrating, and lack of communication from interviewees on transcript approval can be time consuming.

There are multiple issues on the theoretical side as well. Some that always come with oral histories are the power issues: the interviewer hand-picked the interviewee, the interviewer has the microphone, the interviewer has the connection to the archive, etc. Add to that the interviewer is a white American guy and the interviewees are typically black Africans (often with a long history and deep understanding of colonialism), and these issues can be magnified. It comes out in some of the interviews that are upcoming, and in one that was requested not to be in the archive. But that’s part of why we put them up, because that in itself is interesting to some people.

Lastly, interviewing artists is a delicate task, because an artist’s identity is so intricately intertwined with the artist’s career. Some artists flat out do not want to talk about life outside of their work or their most recent album, despite the fact that we’ve informed them of what the interview is going to cover (their personal narrative). When so much of the artist’s life is in the spotlight, having an interview probe some areas typically left in the shadows can be uncomfortable and downright scary. So, again, it’s important that we provide the protected space in which interviewees can narrativize their stories–part of which is making sure they know they can edit the transcript before it is published.

Have you arrived at some working definition about “who is African enough” to be included in the oral interview archive?

We toyed with this question a bit at the beginning of our process. What we came to realize, though, was that we’re trying to add voices to the conversation rather than create categories. Moreover, the longer we spent debating this particular issue, the less time we spent doing actual work. As it stands, we look for some nexus to African creativity, but we’re going as broad as our funding, i.e., shop sales, permit.

Finally, related to the previous question, you’ve written that some of the interview subjects have raised questions about a project on African creatives started and run by two white Americans?

Finally, related to the previous question, you’ve written that some of the interview subjects have raised questions about a project on African creatives started and run by two white Americans?

We started African Lookbook because we’re passionate about it. We’ve both lived and worked around the continent, and then we found each other. “We didn’t choose it” sorta thing. Same goes for our skin colors and nationalities. If we find people–from wherever–who are as excited about the project as we are, we’d love to have more members of the team.

* That’s Aaron and Phil in the photo above taken at Phil’s wedding in 2011.

African Cup of Nations Preview: Nigeria’s Super Eagles back; cautiously optimistic (for once)

Post written by Cheta Nwanze from Lagos*

Post written by Cheta Nwanze from Lagos*

Nigeria has not done well on the continent for quite a while. And by well, we mean we have not won it since forever. Let’s get real, a child who was born in 1994 is right about ready to start having its own kids, so it is that long since Nigeria won the African Cup of Nations.Most people here in Lagos are not as optimistic as we have been in the past because what makes it even worse is that we even failed to qualify for the last AFCON tournament. A previously unheard of “achievement”. Then to make things even worse, we are now saddled with a coach (Stephen Keshi) who has a reputation for fighting with his players. A solid mix if you ask me.

However, there is a school of thought that believes Nigeria may do better than expected starting next Monday in South Africa. I tend to subscribe to this school of thinking and will give the reasons below.

First, the expectations this time are low. All the years of disappointment in the past never seemed to dampen the belief that Nigerians had that, at least on the African continent, the Eagles were anointed to win any and every game they played, and by a handsome margin in the least. The first chink in that armour appeared when we failed to qualify for the 2006 World Cup. But that sense of destiny was finally blown to pieces when we failed to qualify for the Nations Cup in 2012. Nigerians finally appear to have a reasonable level of expectations from the team. To add to that, the fact that a lot of our players are not doing as well in Europe, in our eyes at least, as in previous seasons makes people unsure of what to expect from the team. You only need to listen to Nigerian radio and television to note that the excitement that used to accompany the Nations Cup previously, is simply not there now. I think this lack of fan pressure will make for better conditions, less intensity, less scrutiny. The kind of things that have for too long distracted Nigerian sides.

Another reason that I think the Eagles will do well in South Africa is that for the first time in quite a while, we have a good blend of experience and genuine youth, brawn and brain, home- and Europe-based footballers. What this means is that there are enough hungry players in the team who are angling for moves to the big leagues and know that this is probably the only opportunity they have to impress the scouts who will no doubt cluster at the Cup of Nations. With the experience of players like Joseph Yobo, things can be calmed down such that the occasion will not get to the heads of some of the younger players. Again, with this blend, Keshi now has the ability to change things to suit the variable conditions he might meet on the field. Then there is the surprise factor…

My third reason for optimism is that we have Ahmed Musa, Victor Moses and above all, Emma Emenike. Providing all three can stay fit, I am very optimistic that the team will score goals from the chances that will definitely be created. You see, unlike a lot of others, I think that a midfield built around John Michael Obi is an excellent prospect. Mikel is, at the moment, Nigeria’s only genuine world class player. While a lot of people here are unhappy that he did not turn out to be the reincarnation of the great Jay-Jay Okocha, Mikel has remained a regular in the Chelsea first team. Granted, he appears to have retrogressed and, to be honest, does not occupy the same orbit as Lionel Messi nowadays, but the fact is that Mikel has time and again proved to be a big game player. He frustrates fans with his jeje style of play, but ask the guys he is on the field with, and Lampard as an example will tell you without equivocation that Mikel is essential to Chelsea. Look at his role in the last three games of the 2011/2012 Champions League. I think that the inventiveness of Nosa Igiebor, the industry of Ogezi Onazi and the calming influence of Jon Obi Mikel is a great combo.

Despite all my reasons given above, this Nigerian team is far from the finished article and we must keep our eyes on the real ball, which is next year’s World Cup in Brazil. However, there is a window of opportunity here as the two great teams from the last decade, Cameroon and Egypt, are missing. Cote d’Ivoire, I firmly believe, are well past it and will not win in South Africa. I don’t think that the other strong team on the deck, Ghana, have the balance required, not without Kevin Prince-Boateng, and Dede Ayew. Zambia, the defending champions, have won what I think will be their only ever Nations Cup. So, I will go out on a limb and make Nigeria slight favourites for the 2013 African Cup of Nations.

Nigeria play their first match in Afcon 2013 against the Burkina Faso on Monday January 21 at 18.00 GMT.

* Cheta Nwanze is just another Nigerian who supports the national team, and Juventus. You can find him on his blog, Chxta.blogspot.com.

Don’t forget to join our Fantasy Football league for the tournament where you can test your football knowledge against ours – our league pin is 9132137935284.

Our African Cup of Nations 2013 predictions

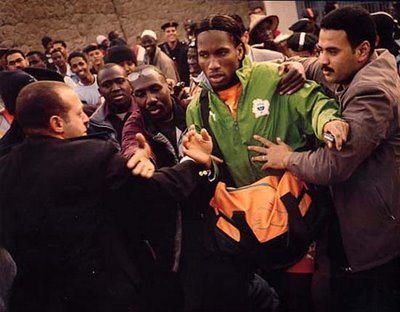

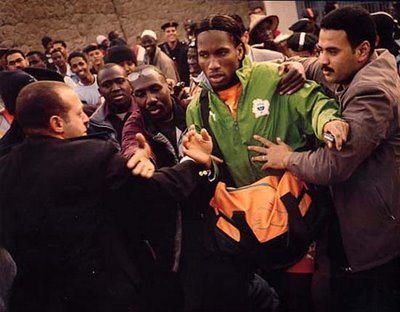

Expect to see a lot more of this sort of thing from the Black Stars. The team does love a dance.

So first we gave you the back story. Now here’s our official predictions for the African Cup of Nations 2013. We’ll have more detailed team profiles by fans of each country coming up in the next few days, and if you think we’ve got it horribly wrong about your team don’t be shy about calling us out in the comments, especially if you’re Zambian or South African. (Also, don’t forget to join our Fantasy Football league for the tournament where you can test your football knowledge against ours – our league pin is 9132137935284.)

Group A

Angola | Palancas Negras (Sable Antelopes) | Ranked 83 in world, 20 in Africa

Player to watch: Manucho, as always.

No goalkeeper is safe when Manucho is around, and Angola will be relying on the former Manchester United netbuster once again in South Africa. Will they be relishing their Lusophone derby vs Cabo Verde and who will the Brazilians and Mozambicans be rooting for in that one? | Prediction: Group stage exit

South Africa | Bafana Bafana (Boys Boys) | Ranked 76 in world, 19 in Africa

Player to watch: Steven Pienaar, but he’s at home in Liverpool.

They’re rubbish. But home advantage is always a huge boost in international tournaments and Bafana Bafana have the bare minimum of quality to make it count (they’re not as bad as Equatorial Guinea were last time). | Prediction: Undeserved quarter-finalists.

Morocco | The Atlas Lions | Ranked 75 in world, 18 in Africa

Player to watch: Younes Belhanda.

Struggled past Mozambique in qualifying but Morocco have quality. Defensive rock Mehdi Benatia is known as the “Moroccan Maldini” and Belhanda is a top class playmaker. | Prediction: Group stage exit

Cabo Verde | The Blue Sharks | Ranked 51 in world, 10 in Africa

Player to watch: Djaniny.

A rising force, this will be the Blue Sharks’ first CAN. Stunned Cameroon to qualify and more surprises could be on the way. Wouldn’t it be great to see them make it out of the group-stage? | Prediction: Quarter-finalists

No dancing for Cabo Verde, just a close knit post-goal huddle.

Group B

Mali | Les Aigles (the Eagles) | Ranked 27 in world, 3 in Africa

Player to watch: Cheick Diabaté.

Not for nothing did the Eagles finished third at the last tournament, and they have enough quality to challenge at this tournament. Much may depend on how much power midfield talisman Seydou Keita still has in his legs, but they have some good youngsters in there as well, and the dire situation at home could give them extra motivation in SA (remember when Drogba “single-handedly” ended the war in Cote d’Ivoire?). | Prediction: Semi-finalists

Ghana | Black Stars | Ranked 31 in world, 4 in Africa

Player to watch: Christian Atsu, Kwadwo Asamoah.

Right now Ghana are enjoying a golden age for midfielders. They have the best midfield at the competition, incredible when you consider that star names Michael Essien, Sulley Muntari, Kevin Prince-Boateng and Andre Ayew will all be absent. With Emmanuel Agyemang-Badu and Anthony Annan bossing the middle of the pitch and Kwadwo Asamoah and Christian Atsu offering power and penetration on the flanks, the Black Stars should dominate most of their games in South Africa. But they still aren’t scoring enough goals. That will be the job of new captain Asamoah Gyan, who is off penalty-taking duty after his mother told him from her death bed that he should stop taking penalties, a decision that will come as a relief to Ghanaians everywhere. A more attacking style could see the four-time champions finally end their 30 year wait for another CAN trophy. This team looks fresh and dynamic, and we think this could be their time. | Prediction: Winners

Niger | The Mena (Gazelle) | Ranked 137 in world, 42 in Africa

Player to watch: Olivier Bonnes.

Niger only made their first appearance at a CAN finals in 2012, and they look like making a habit of it. They’d be thrilled to make it past the group stage, though Jonathan Wilson thinks they’re not to be underestimated. | Prediction: Group stage exit

DR Congo | The Leopards | Ranked 103 in world, 30 in Africa

Player to watch: Dieumerci Mbokani.

Two-time African champions, the Leopards are an improving side and boast a dangerous, powerful strikeforce. Coach Claude Le Roy has vast experience. | Prediction: Group stage exit

DR Congo have the best kit in the competition and Dieumerci Mbokani is their number nine. He loves a goal.

Group C

Zambia | Chipolopolo (the Copper Bullets) | Ranked 41 in world, 6 in Africa

Player to watch: We couldn’t decide between Emmanuel Mayuka and Rainford Kalaba.

Reigning champions Zambia head to South Africa with inspirational coach Herve Renard still in charge and expectations at an all-time high. Probably too high, in fact, when you remember just how much of a shock Zambia’s win last year was, and the fact that they only squeezed past Uganda by the skin of their teeth in qualifying for this tournament. They’ll give it a hell of a go, but we don’t think they’ll pull it off again. Defending your title is always tough, and nobody will be underestimating them this time around. | Prediction: Semi-Finalists

Nigeria | Super Eagles | Ranked 63 in world, 13 in Africa

Player to watch: Victor Moses.

Still recovering from their disastrous World Cup 2010, the Super Eagles return to South Africa. A talented side, but can they stay united? Leaving Peter Odemwingie and Shola Ameobi out of the squad looks crazy, but coach Stephen Keshi has shown (again) that he is not to be messed with. | Prediction: Quarter-Finalists

Burkina Faso | Les Etalons (The Stallions) | Ranked 91 in world, 23 in Africa

Player to watch: Jonathan Pitroipa, Alain Traore.

Regular qualifiers, the Stallions reached the semi-finals in 1998 when they hosted the tournament but have otherwise struggled to make an impact. They do have some technically gifted players though (Jonathan Pitroipa is a lovely silky winger), so don’t be too surprised if they pull off a shock against Nigeria or Zambia | Prediction: Group Stage exit

Ethiopia | The Black Lions / The Walya Antelopes | Ranked 118 in world, 33 in Africa

Player to watch: Oumed Oukri.

A dramatic comeback win over Sudan in qualifying took the 1962 champions back to Africa’s elite competition after a thirty year absence. An unknown force at this level. Expect lots of comments about how they’re trying to “prove Arsene Wenger wrong” – it’s a lot of nonsense, all the poor man said was that he’d struggle to name five of their players | Prediction: Group Stage exit

Loads of Ethiopians live in South Africa, and the Walya Antelopes won’t be short of encouragement from the stands.

Group D

Algeria | Les Fennecs (The Fennec Foxes) | 24 in world, 2 in Africa

Player to watch: Sofiane Feghouli.

Algeria’s young team go into the tournament in good form and will hope to return to the glories of 1990, when they won the cup on home soil. Their recent tournament form has been patchy though — they couldn’t even beat England at the World Cup and remember when they were thrashed by Malawi? — and key defender Madjid Bougherra misses out. | Prediction: Quarter-finalists

Togo | Les Eperviers (The Sparrow Hawks) | 93 in world, 24 in Africa

Player to watch: Emmanuel Adebayor, if he doesn’t wander off.

Didier Six’s men return to African Cup competition after suspension, and their main player is back too (at least we think he’s back). Will try to keep it tight and carve out chances for Adebayor, but Group D looks an unforgiving draw for the Togolese. | Prediction: Group Stage exit

Tunisia | The Eagles of Carthage | 45 in world, 7 in Africa

Player to watch: Youssef Msakni.

Champions in 2004, the Eagles of Carthage draw many of their players from local club Espérance. Msakni is always dangerous. Never an easy opponent. | Prediction: Group stage exit

Cote d’Ivoire | Les Elephants | 16 in world, 1 in Africa

Player to watch: Lacina Traore.

With a wealth of talent, Les Elephants go in as clear favourites. Past disappointments should have taught them the perils of an overly defensive approach, and with Drogba still around, Yaya Toure terrifying everyone he comes up against, Arouna Kone in great form, and 6’8” striker Lacina Traore finally getting picked (he’s Sammy Eto’o's strike partner at Anzhi and is the same size as Lebron James), they have a side with the potential to bulldoze this competition. But then we say that every time. No doubt if they finally do it, they’ll celebrate with a rapturous whole-team Drogbacité at Soccer City (some guy called Teju Cole used to write about Didier’s dance back in the day). | Prediction: Beaten finalists, as usual

Just don’t let Didier take a penalty in the final.

An earlier version of this post formed part of the tournament preview I wrote for Selamta, the in-flight magazine of Ethiopian Airlines (check out their online version).

‘Landing on A Hundred’: An Interview with Cody ChesnuTT

The Yoruba have a word–tutu–for cool. Robert Farris Thompson describes it in his book Flash of the Spirit: “As we become noble, fully realizing the spark of creative goodness God endowed us with, we find the confidence to cope with all kinds of situations. This is Ashe. This is character. This is mystic coolness. All one. Paradise is regained, for Yoruba art returns the idea of heaven to mankind wherever the ancient ideal attitudes are genuinely manifested.” The American singer Cody ChesnuTT’s latest album, “Landing on A Hundred,” displays Yoruba cool. The resonation of the album simultaneously evokes legends of soul music and, thankfully, newness.

The Yoruba have a word–tutu–for cool. Robert Farris Thompson describes it in his book Flash of the Spirit: “As we become noble, fully realizing the spark of creative goodness God endowed us with, we find the confidence to cope with all kinds of situations. This is Ashe. This is character. This is mystic coolness. All one. Paradise is regained, for Yoruba art returns the idea of heaven to mankind wherever the ancient ideal attitudes are genuinely manifested.” The American singer Cody ChesnuTT’s latest album, “Landing on A Hundred,” displays Yoruba cool. The resonation of the album simultaneously evokes legends of soul music and, thankfully, newness.

I know you’ve been compared extensively to Marvin Gaye. But, I haven’t read anything about your high use of Michael Jackson in this album. Why have you been so touched by his work and why did you choose this album for his presence to be felt so profoundly?

Michael Jackson was the first one to really turn the light on for me in terms of the doorway to the dream. It was “Off the Wall.” It was the smile. It was the energy. Michael Jackson always represented a burst of light, a beam. That stuck with me. When you internalize things as a kid, you don’t know how they’re going to manifest later in life. So, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Sam Cooke, all these people, I developed a certain feeling about what music should do and how it should move you. How I responded to it. For all I know, all of these things have been trying to come out of me since I was a child. I may have just gotten to the point as an adult where I could really allow myself to build that emotional spirit that drove them to develop their music to touch so many people around the world. They had to be in tune with their heart and spirit in a very pure way. Maybe that’s what’s coming through with this music. That purity that they imparted, that they gave me. I’m returning that now with the music that I’ve been given. It was a feeling. I knew how it made me feel. All those influences seemed to have found their place in “Landing on One Hundred” in a very genuine way.

Meaning making through being?

Yes absolutely. That’s really what it was about. Being there and allowing the music to come and not chasing anything. Just really being a vessel for what needed to come through. Meaning making through being.

You can hear Africa within every aspect of the album. The instrumentation, the arrangements, your voice. How was this African aesthetic weaved into the sound-scape?

How do you explain something like that? Because, you’re really talking about a spirit. I think when people try to quantify what Africa is or how can you be in one country or continent and still embody the spirit and project the spirit? It’s something that you can’t really put into words. When you think about it, you never do. Africa is within you. It’s a part of your make-up. It’s hard to explain, why do you respond to the drums? How can you explain that? It’s a part of the DNA as far as I’m concerned. To make it simple, it’s just the spirit that’s within you that comes through the music, the rhythm, the tones, the melody. It’s whatever you’re hearing. It’s all in a spirit that’s continuous. Each vessel, if it is open, that eternal spirit, shines through.

There’re several members of your family who work with music. Have you had these conversations with them about Africa and cultural continuity, or the spiritual continuity?

The spiritual continuity. The spiritual aspect has come up several times. The African-American experience is rooted in spirituality. Be it the church or any other faith. Judaism, Islam. The spiritual theme is a definite part of the conversations I’ve had. One of my uncles, he had always been known as street savvy, a “boss guy.” He has since been in transition in his own life. When he heard the song, “Til I Met Thee” [video below], it just opened him up to the point where he started to give his own testimony and almost giving his own revelation so to speak about what the song was and how it affected him and what he thought the meaning was.

It’s touched everybody at their core, which was what I really wanted this body of work to do. I really wanted it to find people where they really live. The real issues that really matter to them. Every single day outside of the superficial façade that they have to carry. The things that they are really concerned about. We’ve had many conversations about the spiritual base of the record. A few friends have commented on the African energy and perspective of it. It’s coming through. I was just talking to a friend today about “Don’t Want To Go The Other Way,” and she was saying how it feels like Africa and also like Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground”. The energy of it reminds her of that. It’s a difficult thing to try to explain.

So, your spirit is what translates as what we hear as African. Has there ever been a moment where you’ve encountered someone claiming that you’re romanticizing your African heritage, or where you yourself have feared a sense of un-belonging?

It was never an intent, but if I ever romanticize it, I can’t romanticize it enough. That is the aim, to bridge the gap. That bridge has been under construction for centuries. So, I’m just making a contribution to the process. Each generation has made an attempt to reconnect in some way, be it politically, ideologically, spiritually, musically. And it is happening. We are reconnecting. Hip-hop has been a huge instrument in the two sides connecting again. You go anywhere on the continent — and I haven’t been there yet, but I’ve seen enough images and talked to enough people to know that it is definitely happening. It’s just a matter of what the conversation is once we do connect. What the ideas are. But I don’t think you can romanticize that enough. I don’t think that you can shed light on those connections enough. So I’ll do whatever I can to reconnect, to get a better understanding of my cultural heritage, my identity, all those things. I think it’s a healthy thing. I don’t think it can ever be viewed as something unhealthy or something that negative. I can’t imagine that.

Some American artists have gone to Africa with certain notions, perhaps about the continued existence of a primordial space, and they’ve said they left the continent with an even greater sense of un-belonging.

Yes, so in “Scroll Call,” I acknowledge those contemporary issues in Africa. I’m not romanticizing at all. I’m addressing the issues that are holding the continent back head on. I say:

We’re too hurried to act on the truth, forsaking the ministry to feast with foreign coupes, as in a coup. Now the call is on the first and the last, to come back! So, I’m addressing what has happened very briefly, a lot of what causes the instabilities or the corruption or how we’ve forsaken the real mission, the ministry for self-interest. You constantly hear how certain groups are really growing and evolving and you still have all these issues of illness and poverty. I don’t do it just to romanticize it, I am trying to push it forward, and shed light on the fact that there’s a lot of work to be done, but it has to start with an uplifting spirit and an uplifting outlook.

I don’t ever feel like I wouldn’t belong. That never enters my mind because I’m not looking for anyone to say, ah yes! You belong! You just have to know that you do! You claim it. You’re not looking for permission, you’re not looking for validation. You’re just saying, this is what it is. I was walking with a friend of mine in Brooklyn who’s been to the continent several times, and we saw this one cat walking down the street. My friend said, man, he could be walking down the street in Sierra Leone. I know someone there who looks just like him! And women, when you sisters walk, it’s the same walk! So at that point, do you say, well how did you get that walk? Are you romanticizing the body language of African women? No, it’s just what it is.

James Brown wound up giving Fela Kuti what he needed and Fela Kuti was going back on the soil. And God knows how many Afrobeat cats took their cue from James Brown. What was it that made them connect? It was something beyond “you’re in America and I’m in Africa.” When I hear them, I know exactly what that is, and when they hear me, they know exactly what that is.

We’re in a realm beyond any geographical location.

Personally, if I romanticize anything, I romanticize the south. For me, the south is the embodiment of Africa within the US. You told me before that you live in Tallahassee, Florida, where the slave quarters used to be.

Right, slave quarters, and they’re quite a few plantations not too far from me.

And you said that there’s one man, about 25 years your senior, who still doesn’t look at people…

Yeah, he still has an issue looking people in the eye when talking to them.

So what does it mean to have that heritage? How does that impact you? Watching that, and simultaneously being.

Simply, it reminds me of the robbery of strength and manhood. How we are still fighting on so many levels just to regain that back. Just the human being, the man. We’re still reaching out to reclaim that. Still building that up. When I see things like that, it reminds me of what’s been taken away but at the same time it inspires me to allow my work and my strength to shine even brighter. And to come forward even stronger, because I’m not just doing it for myself, I’m doing it for him and other people. It makes my head go up a little higher and strengthens my gaze when I’m speaking to anybody. I bring all of that to my process, getting the back strong again, getting the mind strong again, reclaiming the dignity and respect. Just simple fundamental things like that.

Once the creative process has been finalized and produced, how do you then bring that back to these same communities? They’re reflected in this music as well, but it seems much harder for people to connect with spirit.

During that period, the 10 years, part of the process for me was to try to find something that was very accessible. The music is still fighting for them. The song, “Everybody’s Brother” [Youtube video below], a lot of people can relate to those characters in the song. Just that simple phrase, no turning back, can be so meaningful for a community like this. Really anywhere. In France. Even those who don’t have issues of trying to make ends meet or where their next meal is coming from, still have personal struggles or issues they’re trying to move beyond or grow beyond. They can take hold of that too.

Here in the rural part of Tallahassee, as well as those parts in the city where the universities are, this is about the human portion that people can find a piece of their own life in. That is how I see it coming back to the people who inspired the music. It’s really interesting right now to see how to approach radio in this area. I don’t think anyone has played the album here yet. I’m thinking I’m just going to have to go to the radio station and try to find someone who has an inroad to the personalities and present them with the music and ask them one simple question. Is there anything on this album that you think the community can use? That’s all I want to ask. Because it’s mindblowing how no one is playing the album in this region. Especially since the musicians from Tallahassee seem like they would want to get behind it and support it. Maybe they don’t know it exists. Maybe it’s just all in time.

I want the music to touch people in a way where they say, I know this isn’t part of my radio program, but this is something I just had to play. That’s what I’m hoping will happen. I have to trust the spirit in the music and how it speaks to other people and how it will move them to whatever decisions they need to make in terms of how they share it with the community. How they use their resources to turn people on. That’s what “Landing on a Hundred” is for me. When I first submitted the album cover to Polydor France, some of the early feedback I got from it was, are people going to think he’s a reggae artist? They had to understand, these colors existed before reggae. Reggae adopted these colors because of what they represented. These colors represent the spirit of a people. There’s a story here. There’s an identity here. And I’m using all of that. Symbolism, the colors, the vibe, the music, the horns. Everything I can to say that this spirit is still alive and you don’t know how it’s going to come.

Key and Peele Unchained

Sean has blogged here before about the American sketch comedy duo Key and Peele. Around the same time I also came to learn about them after a friend had introduced me to the show. Before giving it to me, he said “it’s like Chappelle’s Show but for today.” These words rang in my ears for days. Dave Chappelle’s straight talking commentary on racial disparity in America combined with goofy abandon was a joy to watch, and honestly, just damn funny. Would Key and Peele be like Chappelle or better?

Sean has blogged here before about the American sketch comedy duo Key and Peele. Around the same time I also came to learn about them after a friend had introduced me to the show. Before giving it to me, he said “it’s like Chappelle’s Show but for today.” These words rang in my ears for days. Dave Chappelle’s straight talking commentary on racial disparity in America combined with goofy abandon was a joy to watch, and honestly, just damn funny. Would Key and Peele be like Chappelle or better?

Key and Peele is framed as a smart sketch show on race relations in America by two “bi-racial” men Keegan Michael Key and Jordan Peele (they both have white moms, they tell us). I found most of their skits funny, but lacking the ballsy commentary and unashamed black perspective that Chappelle’s Show had. However, it was their slavery skit, and the piece preceding it that really annoyed me. Here’s the sketch:

What’s not included in the video above was their introduction to the live studio audience where Peele announces: “OK, so Africa is a fucked up place.” To which Key, seemingly surprised, responds in a disingenuous defense of Africa: “You wouldn’t want to see the Nile? The plains of the Serengeti?” Which is really just the vehicle for which Peele’s lambasting can continue: “You have flyover states. Now, to me that’s a flyover continent.” And the pièce de résistance: “Slavery was an awful thing. Silver lining? It got my ass out of Africa.” The follow up to which was the skit depicting two slaves who get increasingly jealous that no one is bidding for them at the slave auction.

At least in Django Unchained the slave traders got shot (cc: Spike Lee).

Part of the critique of Key and Peele has been that they are “edge-less” and very self-conscious to not offend anyone. Yet, how come they seem to have no qualms in making Africa the butt of an ignorant joke? Is our offence not taken as seriously? Is it really worth it to bring up something as painful and criminal as slavery when the joke is still on the black guy? Why even go there?

Comedy Central clearly seeks to fill the void left by Dave Chappelle when he famously walked away from his wildly popular show (and a $50 million contract!) in the middle of the third season. He claimed that with the $50 million came huge pressure and interference from the network. While Key and Peel frame themselves as “bi-racial” and thus able to occupy both black and white spaces and identities, black people bear the brunt of their humor in all of their skits. White supremacy isn’t questioned at all, while black masculinity is fair game. Which makes you wonder, who is their actual audience? What strings are Comedy Central pulling behind the scenes? Again, Kartina Richardson said it best when she wrote of them in Salon: “Key and Peele fail to ever address the violence of racism, literal or figurative, and this timidity leaves their material lifeless.” In other words, get real about social disparities, and your work will be funnier.

The show has done exceedingly well, with an endorsement by US President Barack Obama himself (after watching their skit of Obama needing an anger translator, which is actually pretty funny and rings true) and they have recently announced a third season. Let’s hope in the future they are able to get to the root of the issues they make fun of: black masculinity, slavery, and racism; and then make fun of that.

January 16, 2013

A Very Short History of the Africa Cup of Nations

The big kick-off is nearly upon us. Just 11 months after that extraordinary Zambian triumph in Libreville, starting Saturday we have another month of football ahead as Africa’s top teams (and South Africa, there as hosts) fight it out to be Champions of Africa. We’ll be covering the tournament more intensively this time around, in cahoots with the BBC’s African football platform, Love African Football (on Twitter and FB). All on our brand new page: Football is a Country, for which we recruited a slate of informative bloggers and already have a dedicated Facebook page. We’ll start with a very brief and very selective tournament history.

The big kick-off is nearly upon us. Just 11 months after that extraordinary Zambian triumph in Libreville, starting Saturday we have another month of football ahead as Africa’s top teams (and South Africa, there as hosts) fight it out to be Champions of Africa. We’ll be covering the tournament more intensively this time around, in cahoots with the BBC’s African football platform, Love African Football (on Twitter and FB). All on our brand new page: Football is a Country, for which we recruited a slate of informative bloggers and already have a dedicated Facebook page. We’ll start with a very brief and very selective tournament history.

Thrills and Spills since 1957: a potted history of the Africa Cup of Nations*

The very first CAN was organised to mark the Confederation of African Football’s (CAF) official launch in Khartoum in 1957, making Africa’s continental prize three years older than its European equivalent. The competition has always been about more than “just” football. One of CAF’s founding fathers, the influential and charismatic Ethiopian Yidnekatchew Tessema, would later gave a stirring speech in Cairo in 1974 in which he laid out a vision of football as a force to unite the continent.

I’m issuing a call to our general assembly that it affirm that Africa is one and indivisible, that we work towards the unity of Africa together … That we condemn superstition, tribalism, all forms of discrimination within our football and in all domains of life. We do not accept the division of Africa into Francophone, Anglophone, and Arabophone. Arabs from North Africa and Zulus from South Africa, we are all authentic Africans. Those who try to divide us by way of football are not our friends.”

But when CAF was founded in 1957, many African countries were still struggling to win independence from European colonial rule, and only three nations took part in the first competition. South Africa (a founding member) had been banned from the tournament after its apartheid administrators refused to field a racially mixed team, and so just two matches were played, with Ethiopia given a pass to the final. Egypt narrowly defeated hosts Sudan 2-1 in their semi-final, before blowing Ethiopia away 4-0 to become the first ever nation to be crowned champions of Africa. Pharoahs striker Mohammed Diab El-Attar put in a performance that would never be forgotten, scoring all four of Egypt’s goals. One of the great figures of mid-century African football “Ad Diba”, as he was known, went on to appear at another Nations Cup final in Addis Ababa nine years later, but this time as the referee, having swapped his shooting boots for a whistle.

The number of competing nations grew rapidly as independence movements began to triumph across the continent. In 1960, 16 nations won their independence and by the 1962 tournament there were so many teams wanting to compete that qualifying rounds had to be introduced. Newly independent Ghana swept to victory twice in a row in 1963 and 1965, inspired by their soccer-mad president Kwame Nkrumah. In line with Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism, Ghana’s Black Stars borrowed their famous nickname from the radical Jamaican intellectual Marcus Garvey’s shipping line, which was established to take black Americans “back-to Africa”. The stars of the 60s were Ghana’s Osei Kofi and Cote d’Ivoire legend Laurent Pokou (nicknamed “L’Homme d’Asmara” for the 5 goals he scored in a single match vs Ethiopia), who top-scored at both the 1968 and 1970 tournaments.

The number of competing nations grew rapidly as independence movements began to triumph across the continent. In 1960, 16 nations won their independence and by the 1962 tournament there were so many teams wanting to compete that qualifying rounds had to be introduced. Newly independent Ghana swept to victory twice in a row in 1963 and 1965, inspired by their soccer-mad president Kwame Nkrumah. In line with Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism, Ghana’s Black Stars borrowed their famous nickname from the radical Jamaican intellectual Marcus Garvey’s shipping line, which was established to take black Americans “back-to Africa”. The stars of the 60s were Ghana’s Osei Kofi and Cote d’Ivoire legend Laurent Pokou (nicknamed “L’Homme d’Asmara” for the 5 goals he scored in a single match vs Ethiopia), who top-scored at both the 1968 and 1970 tournaments.

The 1970s was a great decade for Central African nations, with Republic of Congo’s 1972 victory followed by Zaire’s in 1974 (they’d already won the competition as Congo-Kinshasa in 1968). West African sides dominated through the 1980s and early 1990s. This was also an era of great players: Hassan Shehata (he would later coach Egypt to three Cup of Nations victories), inventor of the blind pass Lakhdar Belloumi, Théophile Abega (who passed away late last year), Thomas N’kono (Gianluigi Buffon decided to become a goalkeeper after watching N’kono’s performances at Italia 90, and named his son after him), Rashidi Yekini, Abedi Pele, Roger Milla (so good he got his own song), Rabah Madjer, Kalusha Bwalya and George Weah (click on the links, the videos are tasty). Then in 1996, the last time South Africa hosted the tournament, Bafana Bafana had their own “Invictus” moment to savour.

Since the turn of the millennium, the tournament has been the stage on which the likes of Samuel Eto’o, Mohamed Aboutrika, Jay-Jay Okocha, Patrick M’Boma, Hossam Hassan and Didier Drogba have shone. CAN has been dominated since 2000 by Cameroon (back-to-back winners in 2000 and 2002) and Egypt ( three-in-a-row between 2006 and 2010). Both of those heavyweights are missing for the second tournament running, after Bob Bradley’s Egypt lost to Central African Republic and Cabo Verde beat Cameroon.

Since the turn of the millennium, the tournament has been the stage on which the likes of Samuel Eto’o, Mohamed Aboutrika, Jay-Jay Okocha, Patrick M’Boma, Hossam Hassan and Didier Drogba have shone. CAN has been dominated since 2000 by Cameroon (back-to-back winners in 2000 and 2002) and Egypt ( three-in-a-row between 2006 and 2010). Both of those heavyweights are missing for the second tournament running, after Bob Bradley’s Egypt lost to Central African Republic and Cabo Verde beat Cameroon.

No team looks to be very far ahead of the rest, and, refreshingly given Spain’s recent domination of the World Cup and European Championship, this year’s Africa Cup of Nations is as open a tournament as you’ll find in international football.

No team looks to be very far ahead of the rest, and, refreshingly given Spain’s recent domination of the World Cup and European Championship, this year’s Africa Cup of Nations is as open a tournament as you’ll find in international football.

Don’t forget to join our Fantasy Football league for the tournament where you can test your football knowledge against ours – our league pin is 9132137935284.

* With thanks to Peter Alegi and his book African Soccerscapes, and Steve Bloomfield and his book Africa United. An earlier version of this post formed part of the tournament preview I wrote for Selamta, the in-flight magazine of Ethiopian Airlines (check out their online version).

A Very Short History of the African Cup of Nations

The big kick-off is nearly upon us. Just 11 months after that extraordinary Zambian triumph in Libreville, starting Saturday we have another month of football ahead as Africa’s top teams (and South Africa, there as hosts) fight it out to be Champions of Africa. We’ll be covering the tournament more intensively this time around, in cahoots with the BBC’s African football platform, Love African Football (on twitter and FB). All on our brand new page: Football is a Country for which we recruited a slate of informative bloggers.We’ll start with a very brief and very selective tournament history.

Thrills and Spills since 1957: a potted history of the African Cup of Nations*

The very first CAN was organised to mark the Confederation of African Football’s (CAF) official launch in Khartoum in 1957, making Africa’s continental prize three years older than its European equivalent. The competition has always been about more than “just” football. One of CAF’s founding fathers, the influential and charismatic Ethiopian Yidnekatchew Tessema, would later gave a stirring speech in Cairo in 1974 in which he laid out a vision of football as a force to unite the continent.

I’m issuing a call to our general assembly that it affirm that Africa is one and indivisible, that we work towards the unity of Africa together … That we condemn superstition, tribalism, all forms of discrimination within our football and in all domains of life. We do not accept the division of Africa into Francophone, Anglophone, and Arabophone. Arabs from North Africa and Zulus from South Africa, we are all authentic Africans. Those who try to divide us by way of football are not our friends.”

But when CAF was founded in 1957, many African countries were still struggling to win independence from European colonial rule, and only three nations took part in the first competition. South Africa (a founding member) had been banned from the tournament after its apartheid administrators refused to field a racially mixed team, and so just two matches were played, with Ethiopia given a pass to the final. Egypt narrowly defeated hosts Sudan 2-1 in their semi-final, before blowing Ethiopia away 4-0 to become the first ever nation to be crowned champions of Africa. Pharoahs striker Mohammed Diab El-Attar put in a performance that would never be forgotten, scoring all four of Egypt’s goals. One of the great figures of mid-century African football “Ad Diba”, as he was known, went on to appear at another Nations Cup final in Addis Ababa nine years later, but this time as the referee, having swapped his shooting boots for a whistle.

The number of competing nations grew rapidly as independence movements began to triumph across the continent. In 1960, 16 nations won their independence and by the 1962 tournament there were so many teams wanting to compete that qualifying rounds had to be introduced. Newly independent Ghana swept to victory twice in a row in 1963 and 1965, inspired by their soccer-mad president Kwame Nkrumah. In line with Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism, Ghana’s Black Stars borrowed their famous nickname from the radical Jamaican intellectual Marcus Garvey’s shipping line, which was established to take black Americans “back-to Africa”. The stars of the 60s were Ghana’s Osei Kofi and Cote d’Ivoire legend Laurent Pokou (nicknamed “L’Homme d’Asmara” for the 5 goals he scored in a single match vs Ethiopia), who top-scored at both the 1968 and 1970 tournaments.

The 1970s was a great decade for Central African nations, with Republic of Congo’s 1972 victory followed by Zaire’s in 1974 (they’d already won the competition as Congo-Kinshasa in 1968). West African sides dominated through the 1980s and early 1990s. This was also an era of great players: Hassan Shehata (he would later coach Egypt to three Cup of Nations victories), inventor of the blind pass Lakhdar Belloumi, Théophile Abega (who passed away late last year), Thomas N’kono (Gianluigi Buffon decided to become a goalkeeper after watching N’kono’s performances at Italia 90, and named his son after him), Rashidi Yekini, Abedi Pele, Roger Milla (so good he got his own song), Rabah Madjer, Kalusha Bwalya and George Weah (click on the links, the videos are tasty). Then in 1996, the last time South Africa hosted the tournament, Bafana Bafana had their own “Invictus” moment to savour.

Since the turn of the millennium, the tournament has been the stage on which the likes of Samuel Eto’o, Mohamed Aboutrika, Jay-Jay Okocha, Patrick M’Boma, Hossam Hassan and Didier Drogba have shone. CAN has been dominated since 2000 by Cameroon (back-to-back winners in 2000 and 2002) and Egypt ( three-in-a-row between 2006 and 2010). Both of those heavyweights are missing for the second tournament running, after Bob Bradley’s Egypt lost to Central African Republic and Cabo Verde beat Cameroon.

No team looks to be very far ahead of the rest, and, refreshingly given Spain’s recent domination of the World Cup and European Championship, this year’s African Cup of Nations is as open a tournament as you’ll find in international football.

*With thanks to Peter Alegi and his book “African Soccerscapes“, and Steve Bloomfield and his book “Africa United“. An earlier version of this post formed part of the tournament preview I wrote for “Selamta”, the in-flight magazine of Ethiopian Airlines (check out their online version)

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers