Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 505

December 21, 2012

French President François Hollande went to Algeria

Ah, the warm bath of public affection in the post-colony. French President François Hollande’s visit to Algeria this week was a little odd, on more than one count. Algeria is about the last place you’d think a French head of state would engage in what in American politics is called working the crowd and in French is called a ‘bain de foule,’ or a ‘crowd bath.’ But as le Quotidien d’Oran pointed out, this was not about demonstrating love for the visitor. It was about showing off the authority of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. By the same token, the two presidents’ display of Mediterranean friendship hardly masked a deep Saharan rivalry.

Ah, the warm bath of public affection in the post-colony. French President François Hollande’s visit to Algeria this week was a little odd, on more than one count. Algeria is about the last place you’d think a French head of state would engage in what in American politics is called working the crowd and in French is called a ‘bain de foule,’ or a ‘crowd bath.’ But as le Quotidien d’Oran pointed out, this was not about demonstrating love for the visitor. It was about showing off the authority of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. By the same token, the two presidents’ display of Mediterranean friendship hardly masked a deep Saharan rivalry.

Hollande had a lot to do in his two days on the far shore of the Mediterranean. Push a new Renault car plant, which the French company needs. Push for more liberal terms for foreign investment, currently limited to minority shares. And pull to keep the growing Algerian economy tied, as much as possible, to the stagnating French one (that means, among other things, readier access to visas for travel between the two countries, which Hollande had already sent his Interior Minister to discuss).

There was of course the old war to talk about, the one that ended fifty years ago when Algeria got its independence. Hollande shied well away from apologizing for French colonial rule in Algeria, but he did recognize that the “colonial system”—to use Jean-Paul Sartre’s phrase—was “deeply unjust, brutal and destructive.” That was not enough to keep a number of parliamentarians from threatening to boycott his speech before a joint session of the Algerian legislature, but it is a step beyond what previous French presidents have said. It is also in keeping with Hollande’s recent acknowledgement of the massacre of Algerian demonstrators in Paris on October 17, 1961. But anyone expecting a stronger statement of remorse was bound to be let down. Hollande was surely less concerned about disappointing his hosts than he was about provoking his compatriots, both those of European settler origin and those of Algerian Muslim ancestry (even if some figure the latter outnumber the former 3 to 1).

There was also a new war to consider. Hollande’s visit happened to coincide with a vote in the UN Security Council authorizing ECOWAS intervention in Mali. For months, Algeria has been opposed to the prospect of foreign, and especially French, action on the territory of its southern neighbor. Algeria tends to think of Mali as its backyard (many Malian Saharans see the relationship in a similar fashion, although they wouldn’t put it quite the same way). The group known as AQMI, which represents the hard-core of the jihadist groups in Mali, has Algerian roots, and—on the other end of the ideological spectrum—Tuareg nationalism has implications beyond Mali’s borders. France is threatened by the former, but has helped to gin up the latter. Meanwhile, the phrase ‘double game’ hardly captures the complexity of Algerian policies towards Mali. Many Malians object to what they consider the ingratitude of President Bouteflika, who spent part of his country’s liberation war in the southern Sahara and whose nom de guerre was “Abdelkader the Malian.” As they see it, Algeria has done little to help and a lot to hinder Mali’s ability to govern its desert territory in the fifty years since. The fact is that although both France and Algeria have been brokers in previous Saharan rebellions, they have never been honest ones, and they have often worked at cross-purposes. This time around, the crisis is deeper than ever, yet the fact that by most accounts the two countries share at least one enemy—AQMI—is not enough to make them friends.

France and Algeria need each other in spite of their shared, sour history. Yet while they cooperate in the Mediterranean, they compete in the Sahara. No amount of handshaking in Algiers and Tlemcen would earn Bouteflika and Hollande a warm welcome in Bamako or Kidal.

The Trouble with “The Trouble with Aid”

“And the world weeps with them…”, narrates the solemn 70s commentator over images of children in Biafra, bloated by kwashiorkor. These are the opening shots of the documentary film, The Trouble With Aid, which screened on the BBC last week, a documentary by problematising the growth of humanitarian aid through an episodic look at the great crises of the 20th century: Biafra, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Somalia, Rwanda/Goma, Kosovo and Afghanistan. Clearly designed to give coherent shape to the critique of humanitarian aid and its discourses (as opposed to development aid) for a largely uninitiated audience, the film is neat and clear, but reductive. However, where it falters in its explicit intention — to untangle ‘the trouble with aid’, instead creating a whole new knot for itself — it accidentally offers us something far more interesting; that is, the reliance that humanitarian aid has on the moving image. Momentarily throughout, the film flattens the issue of aid to an issue of images, equating disasters to the illusory depth of films, while reproducing the image-reliant rhetorics it critiques through its own edits.

The film begins with the Biafran War, which it cites as the birthplace of humanitarian aid (with that claim the film is not alone). An incredible wealth of archival material illustrates the despair of the situation; the Biafran militia fighting for their independence, and the all-powerful Nigerian army brutally denying it, to the cost of thousands of Biafran lives. This first episode of the film, ‘Biafra: Weapon of Propaganda’ sets up the first problem of humanitarianism, as articulated by interviewee Alex De Waal; “The making of false claims is central to humanitarianism.” Next, it cuts to Patrick Davies, the Director of Propaganda for Biafra during the war, who recalls that the Biafrans first ‘advertised’ their political separatist aims, hoping that the West’s apparently democratic golden rule, the right to self determination, would move them to intervene. It fell on deaf ears. Next, they advertised that the Biafrans were victims of a religious pogrom. Again, silence. Finally, after hiring a PR company, they advertised famine, making ubiquitous the images of children with kwashiorkor, and suddenly, the world responded. In doing so, interviewees in the film estimate they prolonged the conflict by 2 years.

And then, as with many things if they are to receive attention in the West, it became de rigueur; Mick Jagger’s girlfriend sat in furs on a New York pavement signing a petition for Biafra; the ‘cause’ appealed to the cool mix of existentialism and anti-establishment attitudes that were prevalent at the time. It was an Easy Rider image for sympathy, and it worked. Episode by depressing episode, the film resurrects archival material of the ‘care’ staples of Western society, which are inseparable from TV media; the Blue Peter ‘Bring and Buy’ sale appeals in the UK, televised addresses from the glossy-haired John Pilger, Band Aid and Bob Geldof, the birth of the ‘cool to care’ attitude which relied on a non-political approach. Pollack is successful in showing how the post-war generation were desperately seeking something to do — “instead of going to war, we went to famine.”

We only have to remember the explosive #Kony2012 campaign to see how entrenched the bad habits of humanitarianism (the de-politicised representations, the white-saviour complex, the ‘cool to care’ attitude) are common-place in humanitarian media campaigns. In this sense, Pollack’s documentary charts how we arrived at #Kony2012, building a coherent case that it has been a series of compromises, a set of compromised but nonetheless ‘good’ people, that have often worsened and further complicated disastrous situations, primarily in Africa.

But this is the problem. The film opens by claiming it is concerned with what happens when “good people try to help in a bad world.” By setting up these abstract moral terms, the critique is already halted before it goes anywhere at all: in an episode on aid agencies feeling compromised in Goma (in the Democratic Republic of Congo) for providing care to suspected genocidaires — raising the issue of who deserves aid, and at what point an agency should retreat — the film’s critique feels flat because of the false good/bad dichotomy it has already set up for itself (incidentally, there is no mention of other complicating factors like the Congolese government, the Kabila insurgency or the UN). The suspected genocidaires in Goma, by the film’s standards, are the baddies, whereas the aid workers are the goodies. True or not, even in attempting to complicate the narrative by interviewing members of MSF and Care International about context and compromise, the film gets stuck in questions of neutrality, which it already seems to have undermined by its oddly apologetic invocation of a crude moral stance, that humanitarians are unequivocally ‘good’, just compromised by circumstance. But isn’t all humanitarian intervention circumstantial? And what about in Somalia, where members of the US army, engaged in a ‘humanitarian war’ (a contradiction in terms?), shot dead hundreds of people running towards a food hand out?

The film is composed heavily of archival material. Grainy footage of Nigeria in the 70s shifts gradually to the striped-TV feel of amateur footage in the Kosovo camps. Cuts from newsreels, TV appeals, news features and observer journalists together build another portrait; of aid’s reliance on the unquestioned use of images of suffering. The footage is of course uncomfortable, but instantly recognizable. It returns here as a strange nostalgia. A lot of the Ethiopian footage — of hapless musicians crusading with their aid into the Northern regions of Ethiopia — is a painful reminder of the heady triumphalism and self-congratulatory concerts that fuelled the ‘Feed the World’ movement. At one point in the documentary, the French minister for humanitarian aid (at the time) says: “It was a film”. Perhaps the history missing from this documentary is not necessarily how the humanitarian movement grew and wrestled with itself, but how the humanitarian movement grew in close relation to the democratization of moving image technologies; how footage could be sent back to the West, sitting on its coffers of money, food and guns, waiting to be moved by the next de-contextualised sequence on starving children and homeless families, to intervene only if the images were powerful enough. How else can we explain the selective ‘caring’ policy the West employs? ‘The Trouble With Aid’ interviews only a couple of Ethiopian and Nigerian people, who were on the receiving end of the aid. It’s hard not to think of Renzo Martens’s ‘Enjoy Poverty’ (read the AIAC interview) the much-debated film which encourages Congolese people to sell their poverty as a resource, given that it is a commodity that the West are willing to deal in, via aid agencies. Martens’s film damns the circulation of images too; he drives home the point that aid heavily relies on images of suffering, and by being acutely aware of his own presence in Congo, he illuminates the fact that ‘regular media’ does not deal with its own presence, and requirements, in other people’s suffering and the promotion of it. In the film, he suggests that Africans should harness their suffering and poverty, via images, as their market capital. Although problematic, some of the issues Martens raises are incredibly appropriate for Pollack’s film, which delves into the moving image archives of humanitarianism, but never once questions those image, or their capture, usage and circulation.

So, in 2012 it was #Kony2012 and Uganda, and in 2013…? Let’s wait and watch some YouTube.

Waiting for Superman*

South Africa’s Mail & Guardian reported a few days ago that the secretary of Shabir Shaik (the Jacob Zuma associate comvicted of fraud) once testified in court that her boss “has to carry a jar of Vaseline because he gets fucked all the time (by politicians), but that’s okay because he gets what he wants and they get what they want.” If South Africa is going to escape its current social malaise, we heed Shaik’s prudent advise and cease waiting to be violated by our political class (with the help of capital). The idea that leadership is the panacea to South Africa’s varied troubles, is asserted as an almost axiomatic truth amongst South Africa’s monotonous punditry. If only we had responsible, efficient, dedicated and competent leadership we would be on the road to economic growth and the subsequent real transformation derived from an increase in GDP. This fantasy is expressed in various forms from the consistent growth of the Nelson Mandela cult (see the recent op-ed by former New York Times editor Bill Keller’s about South Africa; he ended by proposing Mamphela Ramphele for South African President) to the opposition Democratic Alliance’s vaunted Cape Town model, to — a recent entry into the nation — the debate of the so-called ‘Lula Moment.’

This vapid bullshit deserves to be condemned to the same grave of irrelevance as Tony Leon (remember “Take Back”), Herman Cain and Ja Rule. I say this not only because it is bullshit, but because it is dangerous bullshit. It promotes a depoliticized technocratic vision of social change which is meshed with a contradictory worship of politics as a game of big men and the occasional woman. Real talk: If South Africa’s president wasn’t principally concerned with increasing the size of his family and avoiding jail, he wouldn’t make too much a dent in terms of shifting South Africa towards a more equitable and humane society.

The key concepts missing from this discussion are structural power and collective agency. In this a misleading narrative of the apartheid story has come to dominate, namely that of bad people in the form of the National Party (who almost nobody admits to voting for) and of a messianic ANC descending from the heavens to rescue the nation personified in a beatified Mandela. Lacking is a continuous discussion of the nature of the link between apartheid and the form of South African capitalism and the persistence of such awkward features as structural unemployment and an economy sagging under the weight of exploitative monopolies.

Also absent is the collective agency of millions expressed by millions of South Africans in the struggle against apartheid, from individual acts of defiance to the growth of genuine mass movements in the form of the resurrected UDF (United Democratic Front which dominated internal resistance throughout the 1980s) the black trade union of movements, both containing a culture of mass participatory democracy. Ideas of collective leadership and participatory structures which emerged particularly in the 1980s have been subsumed in the search for technical solutions among experts and calls for ‘leadership’.

The language used to describe people has even shifted from ‘citizen’ — an enabling term which has its roots in an idea of democracy being an expression of the will of the people — to the more placid and dull ‘stakeholder’ — with roots in the lexicon of corporate management. Stakeholders wait for services, citizens demand their rights. Citizens participate in the running of the country, stakeholders merely have some stake in it.

Where has this shift from citizen to stakeholder left us? It has left us in the position of waiting passively for some leader to descend from the heavens, solutions in the bag ready to change South African society through implementing technical solutions to the problems of poverty and inequality. In effect it is encouraging a culture of political apathy and a passive population. What this perversely does is in effect encourage incompetent and corrupt leadership. If leaders don’t face the pressure of a political active and engaged citizenry, they are unlikely to seriously challenge the policy status quo which 18 years into our ‘democratic experiment’ leaves the majority in the rut. Furthermore if leaders are not terrified of their citizen’s anger they can get away with looting the trough with encouragement from the private sector.

It seems like the build up to the ANC’s elective conference at Mangaung has been going on for years, millions of words have been written about the clash of the titans finally underway this week: Jacob Zuma vs Kgalema Mothlanthe, Zuma vs Julius Malema, Mothlanthe vs Cyril Ramaphosa and numerous other political battles. Despite the insistence of those within the ANC that a conference is also about policy direction, it has been mostly viewed (and rightly so) as a clash between competing factions seeking to protect their access to power and resources rather than presenting significant ideological or political differences.

If the ANC’s last conference at Polokwane was anything to go by, even if the majority of ANC delegates push through a policy agenda of pro-poor and working class policies, not much will change at all. In the years since that landmark conference in which Zuma came to power on the back of mass support from the SACP and COSATU — the force of the official left — we’ve had Marikana. The majority of South Africans saw little change in terms of their material conditions or ability to hold the government accountable and, in my view at least, the prospects for an actual implementation of the Polokwane resolutions or a new set of pro-working class policies have become even worse.

Instead we have a corrupt and venal political class who have deformed much of the ANC. The ANC, particularly at a branch level, has degenerated into a network for patronage. ANC members are murdered by other ANC members in order to secure one individual or factions access to the particular set of benefits and resources which can be gained from a position in the party or local government. And when people are desperate the fighting gets worse.

Let’s also not forget the price-fixing, monopolistic practices and sheer criminality that passes for normality in the private sector. One need only look at one’s cellphone rates (the highest in the world), one’s banking rates (the highest in the world), the appalling work conditions in say the mining sector or the agricultural sector, or how our corporate leaders siphon off billions to offshore accounts to see that corruption is not confined to politicians.

And the Democratic Alliance of Helen Zille? Far from offering a model of efficiency, accountability and good governance which they trumpet as the ‘Cape Town model,’ they offer nothing more than a party committed to the protection of existing class and racial privileges (basically white privilege), hostile to organized labor and the poor and almost entirely committed to whoring out the country to foreign capital. The safe and allegedly cosmopolitan city center exists side by side with the concentration camp of Blikkiesdorp and much of the Cape Flats. The dirty secret of Cape Town is that it is the most violent city in South Africa, despite the notorious reputation of Johannesburg.

Rather than waiting for a new Mandela to descend and redeem us or for unaccountable technocrats to provide solutions, we should invest instead in building movements capable of putting the heat on our ruling class and building social change from the bottom up. In this we should take inspiration from the wildcat strikes that swept the country earlier this year, we should well do it ourselves instead of outsourcing the responsibility for social change.

* Title changed following a tweet by @bongani_kona.

The cult of ‘leaders’ in South Africa

South Africa’s Mail & Guardian reported a few days ago that the secretary of Shabir Shaik (the Jacob Zuma associate comvicted of fraud) once testified in court that her boss “has to carry a jar of Vaseline because he gets fucked all the time (by politicians), but that’s okay because he gets what he wants and they get what they want.” If South Africa is going to escape its current social malaise, we heed Shaik’s prudent advise and cease waiting to be violated by our political class (with the help of capital). The idea that leadership is the panacea to South Africa’s varied troubles, is asserted as an almost axiomatic truth amongst South Africa’s monotonous punditry. If only we had responsible, efficient, dedicated and competent leadership we would be on the road to economic growth and the subsequent real transformation derived from an increase in GDP. This fantasy is expressed in various forms from the consistent growth of the Nelson Mandela cult (see the recent op-ed by former New York Times editor Bill Keller’s about South Africa; he ended by proposing Mamphela Ramphele for South African President) to the opposition Democratic Alliance’s vaunted Cape Town model, to — a recent entry into the nation — the debate of the so-called ‘Lula Moment.’

This vapid bullshit deserves to be condemned to the same grave of irrelevance as Tony Leon (remember “Take Back”), Herman Cain and Ja Rule. I say this not only because it is bullshit, but because it is dangerous bullshit. It promotes a depoliticized technocratic vision of social change which is meshed with a contradictory worship of politics as a game of big men and the occasional woman. Real talk: If South Africa’s president wasn’t principally concerned with increasing the size of his family and avoiding jail, he wouldn’t make too much a dent in terms of shifting South Africa towards a more equitable and humane society.

The key concepts missing from this discussion are structural power and collective agency. In this a misleading narrative of the apartheid story has come to dominate, namely that of bad people in the form of the National Party (who almost nobody admits to voting for) and of a messianic ANC descending from the heavens to rescue the nation personified in a beatified Mandela. Lacking is a continuous discussion of the nature of the link between apartheid and the form of South African capitalism and the persistence of such awkward features as structural unemployment and an economy sagging under the weight of exploitative monopolies.

Also absent is the collective agency of millions expressed by millions of South Africans in the struggle against apartheid, from individual acts of defiance to the growth of genuine mass movements in the form of the resurrected UDF (United Democratic Front which dominated internal resistance throughout the 1980s) the black trade union of movements, both containing a culture of mass participatory democracy. Ideas of collective leadership and participatory structures which emerged particularly in the 1980s have been subsumed in the search for technical solutions among experts and calls for ‘leadership’.

The language used to describe people has even shifted from ‘citizen’ — an enabling term which has its roots in an idea of democracy being an expression of the will of the people — to the more placid and dull ‘stakeholder’ — with roots in the lexicon of corporate management. Stakeholders wait for services, citizens demand their rights. Citizens participate in the running of the country, stakeholders merely have some stake in it.

Where has this shift from citizen to stakeholder left us? It has left us in the position of waiting passively for some leader to descend from the heavens, solutions in the bag ready to change South African society through implementing technical solutions to the problems of poverty and inequality. In effect it is encouraging a culture of political apathy and a passive population. What this perversely does is in effect encourage incompetent and corrupt leadership. If leaders don’t face the pressure of a political active and engaged citizenry, they are unlikely to seriously challenge the policy status quo which 18 years into our ‘democratic experiment’ leaves the majority in the rut. Furthermore if leaders are not terrified of their citizen’s anger they can get away with looting the trough with encouragement from the private sector.

It seems like the build up to the ANC’s elective conference at Mangaung has been going on for years, millions of words have been written about the clash of the titans finally underway this week: Jacob Zuma vs Kgalema Mothlanthe, Zuma vs Julius Malema, Mothlanthe vs Cyril Ramaphosa and numerous other political battles. Despite the insistence of those within the ANC that a conference is also about policy direction, it has been mostly viewed (and rightly so) as a clash between competing factions seeking to protect their access to power and resources rather than presenting significant ideological or political differences.

If the ANC’s last conference at Polokwane was anything to go by, even if the majority of ANC delegates push through a policy agenda of pro-poor and working class policies, not much will change at all. In the years since that landmark conference in which Zuma came to power on the back of mass support from the SACP and COSATU — the force of the official left — we’ve had Marikana. The majority of South Africans saw little change in terms of their material conditions or ability to hold the government accountable and, in my view at least, the prospects for an actual implementation of the Polokwane resolutions or a new set of pro-working class policies have become even worse.

Instead we have a corrupt and venal political class who have deformed much of the ANC. The ANC, particularly at a branch level, has degenerated into a network for patronage. ANC members are murdered by other ANC members in order to secure one individual or factions access to the particular set of benefits and resources which can be gained from a position in the party or local government. And when people are desperate the fighting gets worse.

Let’s also not forget the price-fixing, monopolistic practices and sheer criminality that passes for normality in the private sector. One need only look at one’s cellphone rates (the highest in the world), one’s banking rates (the highest in the world), the appalling work conditions in say the mining sector or the agricultural sector, or how our corporate leaders siphon off billions to offshore accounts to see that corruption is not confined to politicians.

And the Democratic Alliance of Helen Zille? Far from offering a model of efficiency, accountability and good governance which they trumpet as the ‘Cape Town model,’ they offer nothing more than a party committed to the protection of existing class and racial privileges (basically white privilege), hostile to organized labor and the poor and almost entirely committed to whoring out the country to foreign capital. The safe and allegedly cosmopolitan city center exists side by side with the concentration camp of Blikkiesdorp and much of the Cape Flats. The dirty secret of Cape Town is that it is the most violent city in South Africa, despite the notorious reputation of Johannesburg.

Rather than waiting for a new Mandela to descend and redeem us or for unaccountable technocrats to provide solutions, we should invest instead in building movements capable of putting the heat on our ruling class and building social change from the bottom up. In this we should take inspiration from the wildcat strikes that swept the country earlier this year, we should well do it ourselves instead of outsourcing the responsibility for social change.

December 20, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°16

Filmmaker Shannon Walsh teamed up with director and writer Arya Laloo to make Jeppe on a Friday, “a neighborhood documentary.” The setting is Jeppestown in Johannesburg, South Africa, chronicling a day in the lives of eight residents of this area on the brink of massive change. The featured residents are Beninese entrepreneurs Arouna and Zainab; Ravi, a second-generation Indian shop owner; Vusi, a garbage reclaimer; Alfred, a wedding planner; Robert, who leads a isicathamiya singing group; Mr. Gift, a blind Zimbabwean; JJ, a young white venture capitalist; and sixteen-year-old Lillan, a political refugee.

Joy, it’s Nina – produced in England and Nigeria — is a film built on the experiences and lives of West African women living in the UK who have been separated from their families. The stories are based on news, court reports and director Joy Elias-Rilwan’s own life. Details here and here.

Joy, it’s Nina – produced in England and Nigeria — is a film built on the experiences and lives of West African women living in the UK who have been separated from their families. The stories are based on news, court reports and director Joy Elias-Rilwan’s own life. Details here and here.

La Réunion: Terre d’asile ou Terre hostile (“land of asylum or a hostile land?”) is a documentary by Said-Ali Said Mohamed about racism and prejudices held towards Comorean immigrants in Réunion:

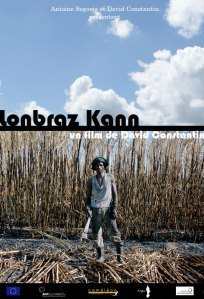

Lonbraz Kann is a Mauritian film project by David Constantin about the sugar cane industry on the island, how it has been affected by the global market, and the wider implications of the sugar demand crash on the island’s society. Or, as the synopsis has it, “Sugarcane is no longer viable, soon there will be only a golf course and luxury villas where it stood.” Here’s the film’s website.

Lonbraz Kann is a Mauritian film project by David Constantin about the sugar cane industry on the island, how it has been affected by the global market, and the wider implications of the sugar demand crash on the island’s society. Or, as the synopsis has it, “Sugarcane is no longer viable, soon there will be only a golf course and luxury villas where it stood.” Here’s the film’s website.

Earlier this year, when it was presented in Cannes, some reviewers found Egyptian filmmaker Yousry Nasrallah’s After the Battle “too complex”. Never a bad sign:

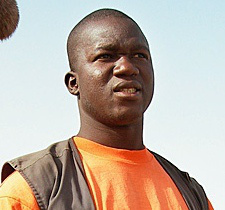

Not unrelated to the Mauritian film above, Faso Fani, La Fin du Rêve (“Faso Fani, the end of the dream”) is a documentary project in production by Michel K. Zongo (left), also the maker of ‘Espoir-Voyage’, about Burkina Faso’s first textile factory — named Faso Fani, or “national loincloth”. In its heyday, Faso Fani was one of the most important factories in the country before it went into decline. Faso Fani finally closed in 2001 under a Structural Adjustment Program imposed on the country.

Not unrelated to the Mauritian film above, Faso Fani, La Fin du Rêve (“Faso Fani, the end of the dream”) is a documentary project in production by Michel K. Zongo (left), also the maker of ‘Espoir-Voyage’, about Burkina Faso’s first textile factory — named Faso Fani, or “national loincloth”. In its heyday, Faso Fani was one of the most important factories in the country before it went into decline. Faso Fani finally closed in 2001 under a Structural Adjustment Program imposed on the country.

Le Djassa a Pris Feu (“Burn it up Djassa”) is a first long-feature by Ivorian director Lonesome Solo. Pitch line: a “noir-tinged urban legend set to the cadence of slam poetry and the beat of street dance”:

Director Nabil Ben Yadir (in the photo left; whose film on first and second generation Belgian-Moroccan The Barons was a local — and highly recommended — hit) is to start shooting his second feature La Marche (“The march”). Synopsis: “The screenplay is inspired by real events and is set back in 1983. For many ‘Arabs’ across France, racist crimes and police brutality are inevitable. Youth from the Minguettes (a neighbourhood in Vénissieux, on the outskirts of Lyon), who are no better armed than the others, decide to stop “hanging out” and to do everything so as not to be considered as second class citizens. In the way of Gandhi, they have the idea of a great non-violent march. With the support of Christophe Dubois, the Minguettes’ priest, they start a ‘March for equality and against discrimination’. From Marseille to Paris.”

Director Nabil Ben Yadir (in the photo left; whose film on first and second generation Belgian-Moroccan The Barons was a local — and highly recommended — hit) is to start shooting his second feature La Marche (“The march”). Synopsis: “The screenplay is inspired by real events and is set back in 1983. For many ‘Arabs’ across France, racist crimes and police brutality are inevitable. Youth from the Minguettes (a neighbourhood in Vénissieux, on the outskirts of Lyon), who are no better armed than the others, decide to stop “hanging out” and to do everything so as not to be considered as second class citizens. In the way of Gandhi, they have the idea of a great non-violent march. With the support of Christophe Dubois, the Minguettes’ priest, they start a ‘March for equality and against discrimination’. From Marseille to Paris.”

Joe Ouakam is a documentary by Senegalese director Wasis Diop about the painter, sculptor, actor and playwright also known as Issa Samb:

And there’s this short film by the directors of When China Met Africa: Madam President, a “behind-the-scenes access” to Malawi’s President Joyce Banda. Wonderful shot: Banda on a visit to Brussels, diving into the city’s tunnels. Quote: “I believe we have so much to learn from China. / How is China!? / We need to go to China!” Final shot: Malawi’s next elections are scheduled for 2014.

‘Race jokes’ in South Africa

South African advertising is known for its eagerness for political commentary; very little ends up being off-limits. Blink Stefanus, or BS Beer (the double meaning for ‘bullshit’ being an obvious choice) is no exception. In September this year the brand won a Pendoring, a local South African advertising award for TV and print campaigns in the Afrikaans language. The price rewarded the campaign for being crafty and different. The beer is not yet widely available, but seems to have some traction in white Afrikaans hipster circles. A few weeks after winning the award, Blink Stefanus released the above video ad.

The premise of the advert is obvious: it’s about race and sex (duh). It begins with a white woman, in her late thirties, looking into the camera. She has a baby in her arms, which is all covered in blankets (this doesn’t give the clue of the joke away at all). She speaks to us in an exaggerated Afrikaans accent:

My name is Mrs. Potgieter. I live here in Sandton. My husband Pieter is a pilot and he is not home very often. But now since I have had the baby I don’t feel so alone anymore. We didn’t think we were able to have children; my husband has had some problems in the past. But now, I think, you know, the Lord works in mysterious ways and now I’ve got a new baby. We named him after Pieter’s father Jasper Gerhardus. Pieter was a bit concerned, but I kept reassuring him maybe it takes a while to develop into their features so after a few months, you know, you could tell if he looks like the mommy or the daddy, but I think when he grows up and into his looks he’ll look like his father. [At this point, the camera zooms in on warthogs on the move.] Yes, I think he’s such a handsome boy. Look at the camera Jasper!

The punchline: the baby is black. And not too many kids named Jasper Gerhardus Potgieter in South Africa are black. You get the point.

Looks like the BS team wanted to be “different,” mixing it up with references to cuckolding/fears of white men’s impotency, and tired, old stereotypes about black virility. The advert speaks to the sexual fantasies that South Africans have about the “forbidden other,” and the continued attempts at denying those desires — even when presented with obvious evidence. But it also plays out apartheid-era propaganda about hypersexual black men, running about raping and impregnating helpless, hapless white women.

Welcome to the new South Africa, where a repackaging of dated colonial fears regarding race, sex, and reproduction can be used to sell beer–and win an award for being “different.”

We asked the man behind the BS beer himself to tell us why this was a winning strategy for selling beer.

To Stefanus, the video should to be viewed in the light of “its marketing philosophy ‘Drink BS, Talk BS.’” As a result, the video should be judged based on its intended meaning: as something “lighthearted and silly.” The crux of the joke and the BS is the secret affair that the woman has clearly had. For him, to suggest a connection between this video and the colonial habit of hypersexualizing the ‘black peril’ is not only oversensitive, it is outright silly (in the non-funny way).

For Stefanus, and many like him, there is no reason to politicize or ascribe additional layers of complication and race politics to a silly video-joke, which is built on a philosophy of tipsy talk and makes fun of something many drinkers identify with: bullshitting about erotic escapades. The joke (in that case) is about sex. Race’s only function in this amusing exercise is to make the sex bullshit visible. (Besides his apparent hyper-fertility, the advert does not attach any characteristics to the boy’s black father.)

But I’m going to have to call BS on this one. Do white guys in South Africa still need to use blackness to crack a sex joke for commercial gain? If all this is just a ‘nonpolitical, silly joke,’ why does so much still depend on race? To say it’s nothing but ‘Drink BS, Talk BS’ ignores those long years of drumming up fears over miscegenation. What is particularly interesting is that the child in the video does not look like it has a black father and a white mother — he is simply a black kid. The advert does not simply echo fears of miscegenation, but emphasizes the eventual erasure of white power: while daddy’s away, he’ll not only be replaced in bed (anyway, he already had problems), but replaced by the next generation — a generation he had nothing to do with begetting.

Woman of the Year

It’s been a busy year for Cameroonian lawyer Alice Nkom, but then again it’s been a busy year for the Cameroonian government, and its various allies, persecuting and prosecuting anyone it suspects of being gay, lesbian, transgender, of a sexuality, feminine, or different.

Alice Nkom was the first woman to become a lawyer in Cameroon. That was in 1969, and she was 24 years old, and she’s been kicking through ever since. Over the last four decades, Nkom has been a leading civil rights and women’s rights activist and advocate in Cameroon, and for the last decade or so has become famous, or infamous, for her defense of LGBTIQ persons, communities and rights.

In February 2003, Nkom established ADEFHO, L’association pour la défense des droits des homosexuel(le)s. The Association for the Defence of Homosexuals (its English name) has suffered threats, attacks, intimidation. Nkom has received death threats. She has been imprisoned. She has been threatened with being disbarred. And she persists and returns to court again and again.

This week, Alice Nkom once again was in the news when an appeals court upheld the three-year sentence of her client Jean-Claude Roger Mbédé, whose crime was sending another man a text message that read, “I’m very much in love with you.” In July, Mbédé was released provisionally, and so this sends him back to jail, to the harassment and assaults “at the hands of fellow inmates and prison authorities on account of … perceived and unproven sexual orientation”. He goes back as well to the general hellhole of Yaounde incarceration, a prison originally built for 600 that now houses 4,000.

In February 10 women were arrested on suspicion of being lesbians. No proof was given. No proof was needed. Suspicion is enough, when it comes to protecting the nation. Men have been arrested and imprisoned for hairstyle and for drinking Bailey’s Irish Cream. These crimes of fashion proved the men were feminine and thus gay and therefore worthy of incarceration. Perception is everything.

All of this is happening, as Alice Nkom has argued repeatedly and to varying degrees of success, in a country that has a modicum of respect for the rule of law, to the extent that it has codified due process. The law that authorizes the current abuses is Article 347, which, somewhat ironically, may not even exist. Again repeatedly and to varying degrees of success, Nkom has argued that the law never passed through the appropriate committees and procedures in the National Assembly.

No matter. Somehow this non-law law has authorized the State disruption of a seminar on HIV/AIDS education and prevention, because there was something in the air about empowering sexual minorities. Perception is everything.

It’s not easy taking the high human rights road to attack the State. In Cameroon those organizations that have argued and mobilized around health issues pertinent to same-sex relationships, and particularly to MSM communities, have fared better in the international sphere, vis a vis funding, and have even received some support from the Cameroonian government. But when Nkom received funding from the European Union, “she was immediately threatened with arrest and a fatwa by pro-government youth groups.”

Last year, when her own arrest seemed imminent, Nkom wrote to leading Cameroonian LGBT activists: “Do not worry for me. I believe I will be arrested in the coming days, but I will not lose sleep over this or, especially, abandon what we have begun together.” It’s been a busy year for Alice Nkom, a year of pushing on, pushing back, pushing forward. Nkom has heard the rumble of violence, menace and threat, and has a direct response: “Threats like these show us that the fight must continue.”

December 19, 2012

Os Kuduristas: Hip as Nationalist Project

Let’s say you’re the son of a very wealthy political leader, from a country that was fighting a long war for independence in the 1970s (remember, that war that’s been reduced to a subplot in a video game). Your father just offered to bail out its former colonial power. It might not have been a great policy move, given domestic demands for infrastructure and social services. But it’s a grand “fuck you” way to say “our economy is booming and you don’t own it anymore.” How do you carry that torch?

Zedu dos Santos (the Angolan president’s son and namesake) got into a music scene with international booty shaking appeal. Last week Os Kuduristas kicked off their first US tour in a packed South Williamsburg bar.

If you missed the pre-tour publicity (they’ve also been hitting Europe), here’s the promo video again:

Back to Williamsburg. The bar was their soapbox for big dance moves and big hair. They had the bartender nervously shoving glass candleholders out of the way when Fogo de Deus climbed up on the bar to do somersaults. Her eyes bulged when he launched into a straight-legged body drop and landed on his side with a straight face. They were very good.

Signs of a big budget do something strange to a dance style started in the musseques and shantytowns of Luanda. But the Kuduristas make no apologizes for their hyper-production. Theirs is an honest effort to package a fun and edgy dance born in Angola as a national product.

Apparently they hired the New York marketing groups Cunning Communications Inc. and Thought Bubble Concepts to do the promotion.

They might also have been responsible for the night’s t-shirt and hat distribution.

But I have to admit; I was a little distracted by the crew (promo team?) they had posted at the door, there seemed to be a lot of women dancing along in matching team jackets.

They greeted New York in Portuguese, saying, “this is Angolan Kuduro, coming to you straight from Angola.” (To which one confused fan cheered: “fuck yeah ethnic music!”) Loud music, aggressive rhythm. Tons of fun.

Their nationalist commitments are played up better on their website.

* In the next instalment Boima Tucker, who DJ’d at the event, gives his take on Os Kuduristas.

December 18, 2012

Redefining “Blackness”: An interview with Toyin Odutola

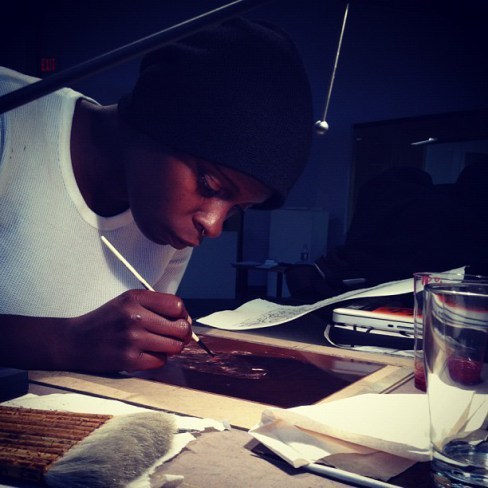

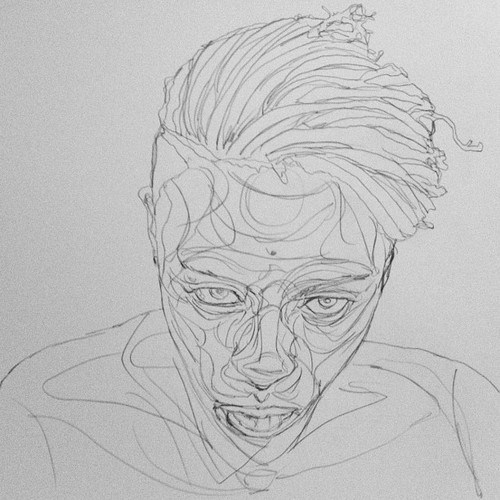

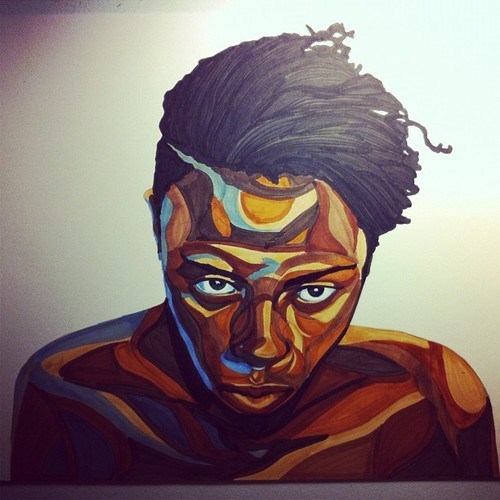

The richly layered portraits of Nigerian-American artist Toyin Odutola have been on the Africa is a Country radar for quite some time. Painstakingly created with marker and ballpoint pen, Toyin’s drawings have been making waves in the art world and across social media platforms. Aesthetically striking in their own right, Toyin’s unique style sparks important questions about the concept of identity. Her pieces tempt us to wonder about the identities that society projects onto us and more reflectively, how we have been sculpted by time into who we are at any given moment.

The richly layered portraits of Nigerian-American artist Toyin Odutola have been on the Africa is a Country radar for quite some time. Painstakingly created with marker and ballpoint pen, Toyin’s drawings have been making waves in the art world and across social media platforms. Aesthetically striking in their own right, Toyin’s unique style sparks important questions about the concept of identity. Her pieces tempt us to wonder about the identities that society projects onto us and more reflectively, how we have been sculpted by time into who we are at any given moment.

2012 has been an important year for Toyin’s progression as an artist. She received her MFA from California College of the Arts, published her first book of drawings — Alphabet, completed two residencies, including one at the legendary Tamarind Institute and exhibited works in numerous group shows including the “Fore” exhibition which is currently running at the Studio Museum in Harlem until March 10, 2013. With a major solo exhibition lined up at the Jack Shainman Gallery in April, the year 2013 is poised to be quite notable for Toyin as well.

We spoke with Toyin about her thoughts on post-racial aesthetics, perceptions of “African” art, androgynous figures and the nostalgic crystallization of past selves through portraiture.

Your predominant style of drawing involves creating a figure with many layers of ink, do the layers contribute to the mapping of the skin’s geography?

Absolutely, in the sense that the process of making layering, is, in essence, geography. I think a lot of people look at my style and they think it’s a means to an end, but honestly it’s the only factor. I think about what other people read in the work and it’s interesting, they find other things that they like, but for me it’s always been the skin. The skin is the most interesting thing. And it’s the reason I go into it as hard as I do. Many people will say “I really like the eyes,” or “I really like how you draw the hair,” but to me that’s embellishment for the skin. It all boils down to the skin. The whole geography of skin thing has kind of shifted I guess, with color — the sort of color pieces that I’m working on — because I think people are seeing that the language is expanding. So for them it’s like, well, are you trying to create a whole new geography, an imagined geography, as opposed to something that’s a little bit more personal to the subject or grounded to reality in any way. I never really was grounded to reality, at all. My work doesn’t look like anything in the real world. So for me it’s always been an abstraction — but it’s an abstraction that is the lie that creates the reality. In the abstraction something real comes forth.

From some of your earlier interviews and then through your book, the way you actually talk about the skin and blackness has evolved and shifted.

I definitely sense that, but I’m also a bit nervous about it, because when I started this whole thing — around 2009 — it was just a means of making me not go crazy, honestly. It was so immersive and I could just lose myself in the meditative form of repetitive archs and puzzle-like form that I would never pay attention to the fact I was homeless and I had no job and I was really depressed. From that really dark place, I gained sort of a thing. For me every time I see the transition I remember that dark place because it was the reason I started.

Discovering and finding comfort in your own identity is a major theme of your book Alphabet, how has your art evolved as your conception of your identity has evolved?

Alphabet was my thesis. The way you present a thesis in my school (CCA) is that you have to talk about everything that your work is about. The program was really immersive and so they wanted you to provide a thorough context for your work. Alphabet became an Oprah Winfrey session, where I just poured out everything and Alphabet, the book, was a much-abridged version of that. It was both cathartic and nice to get it published, like a form, and say: this is my life. On the one hand, I’m this black woman artist, but on the other hand I come from a very specific identity and a very specific string of events. Some of it is recognizable to people and some of it is not. Alphabet was a shift happening in me and I wanted to record it, and I did, and my work has changed with it.

Often in popular discourse, the term “African” is not simply a geographical descriptor, it comes with cultural projections, As a Nigerian-American artist, to what extent is your artwork labeled “African” and how appropriate do you find that branding?

Often in popular discourse, the term “African” is not simply a geographical descriptor, it comes with cultural projections, As a Nigerian-American artist, to what extent is your artwork labeled “African” and how appropriate do you find that branding?

I’m proud that it’s called “African”. And I’ll say that without having an illusion of what Africa is tied onto. Because my work and many works like it are whistleblowers to the illusion of Africa. I think there’s this idea that African artists have this soulfulness that is inherent in the continent and create these grand narratives. But what I’m doing is, literally, drawing people. In a very basic way. With a pen. And that sort of resourcefulness is very African I think. Because you take something that seems very rudimentary, and you really go ham on. That might be something that is distinctly African. On the other hand, I’m specific to being Nigerian, so when I hear “African” it just seems like they’re lumping me into something immediately and not taking the time to research me. It’s annoying because whenever people talk about art history they just talk about Europe; so when you hear artists say “I’m a European artist” people are like “Okay, but say you’re Italian.” They take the time to be specific with Europeans so why can’t they take the time to be specific with me? It just seems kind of lazy.

Sometimes it is a good tag. Sometimes it is not. It’s a love-hate thing. So, again, whenever I hear “African” I don’t really know how to respond to it. I feel very proud to be a part of something that up to this point has been used very negatively; something that has been excluded or omitted in the art world. So it’s really nice to be someone who comes from that continent and says, “Hey I have a voice and you better listen because I have a right to it.” On the other hand it’s getting old because it’s 2012 and people still don’t know where Nigeria is located. It’s always going to be a struggle, probably for the rest of our lives, sadly. Maybe when I’m 40 people will be like, “I totally know where Nigeria is, I totally know about this culture.” The way that they know about France.

As a follow up to that, what do you think when some exhibitions are curated as a collection of “African” artists and they box you in to being an “African” artist as opposed to being a simply an artist?

I just returned from a show of African-American artists [“Fore”] and that was really interesting. I think that was the first time in New York where I was with some high class African-American people. A majority. It’s fascinating to me because we need those things. That’s the sad thing. It’s because of our society that we need those exhibitions, even though they’re something of a double-edged sword in their own way: they’re limiting us to a very specific way of seeing the world — but what they’re aiming to do is bring that specificity for people to come in and they see our universe. But how many people are going to go in without some kind of preconceived notion?

I think whenever anyone lumps me into an African genre, again I’m proud to be in that show, I’m happy that that show even exists, but I don’t want it just to be black people coming to the show, or only Africans. Yes my work deals with that subject matter, but that doesn’t mean you can’t come and see it if you are Asian, Latino or Caucasian. It doesn’t matter to me. It’s the fact that you’re even allowing the time to investigate my work. That is why that African show is needed — often times a lot of black artists aren’t included in shows, unless you’re a super mega artist. If you’re an emerging artist, you need that kind of exposure early on in your career. Not everyone is Kara Walker or Glenn Ligon, for whom it of course also took a while to be who they are. I mean Julie Mehretu took a minute to be Julie Mehretu and she wasn’t even dealing with representational work. It is what it is.

Your works often explore elements of “blackness”, though your portraits depict people with a variety of cultural backgrounds; do you consider the redefinition of “blackness” in your work to be post-racial?

Your works often explore elements of “blackness”, though your portraits depict people with a variety of cultural backgrounds; do you consider the redefinition of “blackness” in your work to be post-racial?

Oooh. That’s such a dirty and weird word, “post-racial”. Thelma Golden is the one who started the idea of post-racial in the 90’s. I don’t think we’re post-racial, ever, until people stop thinking about race. Which is not possible. One of the things that I like about Hank Willis Thomas — the air I breathe — is that he is such a genius in undermining the ridiculousness of race. I posted a video where he boils it down, he says, “[race] has been the most successful marketing ploy in the history of the world.” I just love that. And it’s totally true. Because everything that we think about another race is false. It’s completely false. The whole thing about blackness for me is that I wanted to make the work as dark as possible when I started because I’m a dark person and I wanted to capture what it feels like to be black. And then it just evolved. I started thinking, what if I draw this Asian guy as dark as possible…what does he become? Does he become black because I draw it or because they think he’s black? I even did his hair the way he has it. And still people will be like, “Oh. What is she trying to say?” And I’m like, “No, it’s an Asian guy that I just drew this way.” Suddenly it’s about my experience and my blackness and it’s not about him at all anymore and that’s a really fascinating process for me to digest. I’m the devil’s advocate when it comes to blackness. It’s always going to fascinate me because I’ve been treated a certain way since I was a child because of my blackness, which has been imposed on me. So for me to explore that in my work is to question why I was treated this way and how people read other people.

To me the interesting thing about blackness now is the pen. When you see a black pen, it’s not black at all. I love the moment when people see my work in person and they’re like, “Oh, but it’s not really black?” Taadaa! That’s why I use pen. Because it’s not black. The ink is not black.

These days, if you draw a black figure, because you’re coming from a place where you’ve tried to understand blackness as a concept, are you drawing that figure with a narrative of blackness or is it simply to say this is a person and we don’t have to deconstruct a racial message?

Blackness was a concept in my earlier work. It didn’t have to do with the person, it had to do with the concept of blackness, literally, because I wouldn’t even give them names. I would call them “female this” or “boy that”. I didn’t really think about people until 2011. It was just: here’s a person who is black. And black in itself is twisted, because that is a material description. So before, I was definitely aware of the history of blackness in aesthetics, especially representational aesthetics. When you’re doing portraiture and you’re a black person and you’re portraying black figures, there’s always going to be a loaded history. I had to go through that to get where I am now, which is a very freeing place, where the black figures that I make can be various. The work isn’t limited to that history anymore. And I think it has to do with the time that we’re in. People are more free to be themselves and they’re black, whereas before you had to represent blackness so much and you had to sacrifice a little bit of yourself to do that. Now it’s more like I want to be me and me can be all of these things at once and have nothing to do with black social representation at all.

I actually am a super formalist — a dirty word in art school. No one wants you to be a formalist, you have to have a message. I look at Lucian Freud because he really was the embodiment of his craft being the message. The time it took, the labor, the way of looking at a person, that was the message. Because he drew predominantly white people so no one really assumed anything else. Take Elizabeth Peyton for example. The thing that really infuriates me is that I can’t be an Elizabeth Peyton: painting and drawing people in my life, who aren’t famous and who have no significance besides my connection to them, but I draw them in this way where I’m full-on adorning these people and all the public has to do is digest them as pretty. Peyton’s gotten a little more political recently doing portraits of Kanye West, but of course black people, they’re always political. That’s when her message shifted. I think for me the moment I came out to do the work it was considered political, because it’s the idea of seeing black men, black women, androgynous figures overall, being presented in this way was very different so of course I’m going to have to push a message with everything. But in the end I just want everybody to think “That’s a really pretty blue.” “I like that lash right there.” Because that’s what I see. I see the lashes, I see the fine points, but no one wants to focus on that because it trivializes a bigger issue and I understand that. The bigger issue is that we still have issues of representation in this country and that’s a fucking big problem. Sometimes it’s very frustrating to be an artist in that arena and you’re like, “I don’t want to always have to represent everyone.” But at the same time I have to, because no one else will. It’s the great burden of post-racial artists.

Do you think in your lifetime you’ll be able to get to a place where you’ll be able to transcend race with your art?

Do you think in your lifetime you’ll be able to get to a place where you’ll be able to transcend race with your art?

If you look at black history, especially women artists, usually the moment when they get famous for being what I’m seeking out is the moment they die. Think Zora Neale Hurston or Josephine Baker, women who were very specific about not looking just at race, just at social representation, but rather at the artform itself. Time had to shift. But then I think about people like Toni Morrison who in every essence created works where the foundation has been about blackness and black representation, but she’s transcended it completely. And she’s still alive and she’s still kicking it, but when people think about Toni Morrison, what’s the first think they think about? “Mmm hmmm Negro Spiritual” [singing]. And she’s more than that. So maybe when she passes away – and I don’t wish that upon her – but chances are, that’s when it’s gonna shift. Same with brilliant luminaries like bell hooks and Octavia Butler. I don’t know, maybe in my lifetime…I’m not holding my breath though.

Many of your drawings are self-portraits, what drives you to capture many different variations of your own image?

There’s a Romare Bearden quote that I posted on my website where he talks about how it’s always difficult to draw yourself because you’re always at issue, you’re always changing, especially if you’re an artist because you see everything. Observing yourself is very uncomfortable and you’re more attuned to a shift. It’s very difficult to draw yourself and think that’s it. A mirror isn’t the only form that can capture you, you can do it in so many different ways. Noah Kalina, the guy who takes his photograph everyday, is a brilliant example of that. The idea that you’re always at issue, you’re always changing even when you look exactly the same, with the exact same face, everything is shifting. I draw myself because I want to capture a shift. That’s why I always get tattoos, they’re temporal, they represent a time that’s passed. It’s a moment to take a break and look at myself properly. It’s not just how I look, it’s what has happened. As James Baldwin says, “Where I’ve been and what I’ve been.”

The reason I started doing self portraits in the first place was to see myself. Not just in a mirror or in a photo, To really take the time and look. Through that I’m getting at the psychology of looking, I’m really getting at what I was thinking, what I was feeling. There are moments when I think, “Oh my god I hate my face,” but I also have moments where I think — and it sounds totally narcissistic and it’s not meant to be — “I have a really interesting face.” It’s the same reason why I’ll draw my brothers ‘til the day I die, because they have the most interesting faces. Especially my youngest brother. He’s 6’7” and he’s got these huge eyes and he’s always looking at me with this look of incredulity. He’s like “Really?” I love that. He has so many variations of that “really?” He can do “really?” from the back. He can do “really?” from the side. He can do “really?” looking up.

You were born in Ife, Nigeria, but you have lived much of your life in California and Alabama, all very different cultural environments. How has this plural cultural experience shaped your artwork?

It’s helped in color. It’s helped in tone. It’s helped in creating puzzle-like forms. I always go back to memory when I work. For me it’s constant. They’re not even places I have lived in the past tense, they’re always relived in a way. I’m still there and they’re still shaping me.

Your drawings portray people not only as they are, but often as they were at some previous time; is there a certain nostalgia captured in your pieces for the selves of moments passed?

It’s all nostalgia. It’s all about time. The reason why I’m always obsessed with capturing myself is because I know I’m never going to be that way ever again. There’s this piece I did called All these garlands prove nothing (2012), which I made when I had super long hair. That piece got damaged in Hurricane Sandy and I was really bummed about it. It wasn’t the only one that got damaged, but it was the one that was hit the most. There’s a lot of emotion involved with the series I’m working on now. It’s the idea of literally something lost and what you do in response to that. So I started drawing all the hairstyles I’ve ever had. Which are a lot actually. I had this punk thing, I had an afro, I had long hair. You’d think I was schizophrenic, but it really was just me trying to discover myself and figure out what I can get away with. While I’m working on this piece, even though I’m spending a lot of time on the details, I’m aware that people are not going to see that or it has the potential to be gone. All that time I spent doesn’t matter anymore. The piece doesn’t exist in that same way again. That was a big wake up call recently. The amount of time I spend on my work and what it really means. Does the time spent equal the time that’s lost?

Some of the figures in your drawings appear androgynous, is there a message about gender that you are trying to convey through such pieces?

Some of the figures in your drawings appear androgynous, is there a message about gender that you are trying to convey through such pieces?

I am a huge fan of androgyny. I think more people should be androgynous in portrayals. I embrace the masculine and feminine side of myself and I like to explore that in my drawings. When I draw my brothers in particular, I exploit the feminine. I always give them huge lashes and I always capture them in poses that are not quintessential black male poses. There’s one piece that’s based on a photo I took at the Abuja airport, which is absolute chaos, where my brother’s head is cocked up and there’s a tinge of terror in his eyes. He was trying so hard to be this calm, cool black dude. I loved that. I called the piece Uncertain yet Reserved (2012) because he was reserving everything. He was trying so hard to hold onto his blackness, his maleness, but he was very scared and neither of us knew what was going on. It’s the slight sense of uncertainty where his eyes are wavering. I love that kind of portrayal. The whole point of exploiting that gender construct is to get at the person and not get at the label that society wants to put on them. It’s all about the social construct of an identity and the reality of a person, which are very different things.

I’ve always been some who’s been very androgynous. I’m glad I’m a woman. I love being a woman, but I’m also aware that I have very masculine sides to me. That’s something for black women that you don’t see a lot.

You are a prolific blogger and instagram user, documenting your artistic process and your musings, does interacting with your audience impact your pieces?

I remember when [blogging] was a really weird thing I did on my own and I had ten friends. It was really personal. It was me. I would go back and I would say, “What did I do with that piece again?” and I would literally go back into my archive and I would look it up and watch the different stages because I was so obsessive about documenting everything. I would watch how I had constructed it. No one else gets it but I do so I would look at those pictures and think, “I got it. I know how I did that piece, now I’m going to apply it to this one.” But then suddenly the audience also got involved. There would be questions and it turned into a dialogue. Back then it was a beautiful moment where there were these very cerebral questions that really made me take a step back. I often came up with rather long answers, but it was because I was thinking. What those questions did for me was provide questions for my thesis. Which is what Alphabet is about. That’s why I wanted to publish it — because it started on the blog. If I hadn’t had those questions I don’t think I would be eloquent enough to talk about my work. Dominick Brady would ask questions, and so would Derica Shields — people like that who were thinking as they were seeing my work. I received really hard-hitting questions where it took me three days to respond to. Now I get the questions where someone asks, “How do you figure out your color palette?” I want to say, “Figure it out yourself!” I’m not going to answer everything. There’s a lot of really young people that follow my blog now and I totally get that because when I was 17 I was also wondering, “What oil medium does Lucian Freud use? Does he use linseed oil? Oh my god.” Can you imagine if Lucian Freud had a blog? I would kill him with questions. Every time I get annoyed with questions I imagine Picasso having a Tumblr, I’m sure people would ask him the same thing. Or Matisse.

On your blog Obia the Third, you often share quotes that resonate with you from the likes of Zadie Smith and Virginia Woolf. How does literature inform your artwork?

Well, it’s really great for titles. I’ve always loved reading ever since I was a kid. I remember the first time I read a Zadie Smith book, who I adore. I think she’s the female literary equivalent of me as an artist because she’s always questioning herself and that’s something I do when I work. I love to read interviews with her equally as much as I love to read her books because they are such brilliant windows into her world. Same with James Baldwin. Interviews with James Baldwin are the Holy Grail. He’s so on it, he’s so aware. I’ve read Another Country 50 billion times.

We live in a world where we’re so inundated with visual language that people think they know what they’re seeing when they don’t. So you need literature to hone it into something very specific. I’ve noticed many times when I leave my pieces untitled, peoples’ imaginations will run crazy. So it’s about taking control of what I’m making and getting to a point where I’d like the audience to start from instead of just having them start from wherever they feel like. If you look at any major artist, they have to write something. We can’t just leave it at the art alone anymore. You have to write so you have to know what good literature is. My style is very much a reflection of people I read. Literature allows me to properly talk about my work. If I were ever to meet any of these people I think I would probably cry. I’m terrified too, because I would probably get a restraining order on myself.

But here’s a question, how accessible should writers and artists be? I always question that, especially with my blog. How much is too much? I’m getting to that point where I’m thinking I need to take a break because people start thinking you owe them something. No artist owes you anything. So how accessible do I want to be and how much mystery do I want to keep? I used think mystery was bad for a very long time. I thought I had to be as transparent as possible. And now I’m like, “No, I need to protect myself.” I’ve had a couple shows were people come up and they touch me. And I understand that because I was always someone who was a fan. But now someone is a fan of me, which I find incredibly crazy because I’m a crazy person. Online life and real life interaction is very different for me. If someone is going to message me online, there can be this tone of authority. That’s where I feel the access stops. But if you come up to me in person and you say you just want to talk to me for like 5 minutes, I’ll talk to you. Online it feeds into the fantasy of what I am, but if you talk to me in person you get to see that I’m just me and that I’m awkward and silly.

You’ve mentioned Hank Willis Thomas, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, Lucian Freud and Korehiko Hino among the artists you admire. Who would you most like to collaborate with?

You’ve mentioned Hank Willis Thomas, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, Lucian Freud and Korehiko Hino among the artists you admire. Who would you most like to collaborate with?

Hank is N°1 because he’s such a good collaborator. He’s the collaborator king. Kerry James Marshall too, but I’d be so terrified I probably would end up doing nothing, I’d just watch him the whole time. For a lot of these people I would just want to be in the same studio working with them, but not necessarily literally collaborating. I would love to meet Takehiko Inoue, the guy who did that Vagabond series that I love so much. I just want to be in his studio drawing with him. His energy to me is so inspiring. If you see him work he’s like a machine. He’s making these huge pieces. He’s the only reason that I think I have a possibility of doing large work because he’s doing ridiculous detail.

Hank Willis Thomas has been a part of your career from early on and has facilitated your development as an artist, he clearly digs your work, so what is preventing the Hank-Toyin collaboration from actually happening?

I feel like he’s just so busy, but it’s probably gonna happen. Knowing Hank, something’s gonna come up. The reason I studied at CCA was because of him. He graduated from that school and I thought if this guy went there and was able to make that kind of work, I am in. He’s the reason I’m even having this interview. I joke around a lot, but I owe him so much. He’s been so supportive. He’s the kind of person that you would want as a mentor because he’s honest, he just tells it as it is. In the art world, no one can prepare you for this craziness. It’s so nice to have someone to help you navigate because it is treacherous.

So someday. I hope so. Put it on blast. Say, Hank, I’m ready to collaborate.

You have a solo exhibition scheduled for April 2013 at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City, is there a theme that unifies the pieces you will show at that installation?

I’m trying. I’m all over the place because my interests have been all over the place. Ok, I’ll give you an Africa is a Country exclusive. Amber. That’s all I’m going to say. Every bit of the definition of amber is what I’m really interested in right now. And it’s been making sense for the color choices I’ve been making recently in the last few months. But it’s really hard for me to bring pieces together for a show. Even for [my previous show] MAPS it was like two separate shows. There was a lot of older work and then there was a lot of this new sequential work. At the end of the day it’s probably going to be that way. Two ways of seeing will definitely play into it. I have the whole gallery this time, which terrifies me. I’m excited, but I’m also dreading it a little bit because I really don’t know what people are thinking. At all.

There are a lot of people saying I should do a life-sized portrait. I’ve done full body before. For me whenever I introduce naked bodies it’s a whole other conversation. Do I want to have that conversation? I’ve had people be annoyed that I don’t do full bodies and I just say, “Trust me. There’s a reason I don’t do naked bodies.” I did it before and people think, “Oh my god those are her boobs!” First thing. And then of course it becomes this thing about slavery. People say I’m commentating on that, which I never am. I might do one and make it really uncomfortable for people. Something really inappropriate. And maybe then they will get off my back. But they’ll probably want more. They’ll say, “Why don’t you do 5 more of those pieces?” The full body thing is interesting in the sense of doing something like Laylah Ali’s Greenheads; something that deals with a narrative. If I present a naked body, it’s going to be a group of them doing something. And I don’t want it to be referring to some classical arrangement, I want it to be its own story, in its own world. And that takes time and planning and you really have to know what you want to do ahead of time, which I never do. So it’s not something that’s out of my purview.

In the letter A in Alphabet you describe the people you’ve been during your lifetime; who are you at this very moment?

Still trying to figure that out. I’d say I’m very indecisive. Unsatisfied. A completely self-indulgent draftswoman who came back to the South because she needs to find grounding at a crazy crazy time. Someone who’s questioning her very image and the mythology around people more than ever.

All these garlands prove nothing II (2012)

Toyin was born in Ife, Nigeria and raised largely in Alabama. Her self-published book Alphabet is available here. Find Toyin on Tumblr, Instagram and Twitter. As a tribute to the manner in which Toyin methodically documents her artwork on her blog, the images above illustrate the progression of how her portraits come to life. Some excerpts from the video interview can be found on YouTube.

December 17, 2012

We write what we like about Steve Biko

Had he not died, Steve Biko would have turned 66 years old today. But since the Apartheid police murdered him two months shy of his 31st birthday, we the living are left once more to think, through Biko, about what could have been. This has been a big year for “Bikoists,” as the Johannesburg-based commentator Andile Mngxitama describes himself and his comrades.

Two Biko biographies emerged—one, Steve Biko, is a short, Jacana Press/Ohio University Press pocket book by documentary filmmaker Lindy Wilson; the other, Biko: A Biography, is a greatly anticipated tome by the former director of the Steve Biko Foundation, “internationally respected political analyst and commentator” (in his publisher’s words) Xolela Mangcu.

Separately, Google’s new “Cultural Institute” collaborated with the Biko Foundation to put a “Biko archive” online and accessible to people with an internet connection. Finally, earlier this month, the Biko Foundation (founded by Biko’s son) celebrated the opening of the Steve Biko Centre in Ginsberg, the Black Consciousness leader’s hometown in the Eastern Cape, an event attended by luminaries ranging from Biko’s comrades like Mamphela Ramphele, to Mireille Fanon, daughter of the famed post-colonial theorist and Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s president. As the Biko Foundation put it in a tweet: “The crowd is chanting Biko!!! Biko!!! Biko!!!Biko!!! Ohhhhhhh you have to love Biko’s people. He Lives!” Indeed.

Yet what does it mean for a dead man to live through us, as we chant his name and claim him? Mangcu’s Biko: A Biography is a useful place to start.

Xolela Mangcu (who has a PhD in city planning from Cornell) is well known in South Africa for his columns in the Business Day newspaper and his prolific publications on the post-apartheid era. He also comes from Ginsberg and has close ties to the Biko family. Despite his legend, Biko has never had a full biography, and at over 300 pages, Mangcu’s volume attempts to satisfy that demand. Yet it is an exceedingly odd book.