Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 508

December 10, 2012

The Fairtrade Façade

“Trade not aid” – if you’ve been paying attention to the discourse on how to improve living standards for the world’s poor, it’s a familiar phrase. Over the past decade especially, armchair development experts (and, you know, “actual development experts”) have criticized aid for its failure to bring fundamental change. Meanwhile, virtually anywhere you turn, someone extols virtues of fair trade. But what happens when trade fails in the same fundamental ways as aid?

“Trade not aid” – if you’ve been paying attention to the discourse on how to improve living standards for the world’s poor, it’s a familiar phrase. Over the past decade especially, armchair development experts (and, you know, “actual development experts”) have criticized aid for its failure to bring fundamental change. Meanwhile, virtually anywhere you turn, someone extols virtues of fair trade. But what happens when trade fails in the same fundamental ways as aid?

Take, for instance, the well-known Fairtrade program, which provides a baseline price for crops, allowing farmers protection against price manipulation and encouraging more democratic access to global markets. Criticism of the program has come from all directions; radical leftists revile its acceptance of and reliance on markets, while free-market conservatives dislike the distortions it brings.

These criticisms arise out of the biases of those making them. As far as criticisms based on actual results, economists and others have warned of the program’s ineffectiveness and potential to do harm. Most of the available studies in English have focused on South America, which accounts for over 90% of U.S. coffee purchases. However, a new study by the Forum for African Investigative Reporters (FAIR) confirms that Fairtrade really ain’t so fair for farmers in West Africa either.

According to FAIR, cocoa growers participating in Fairtrade programs in Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire see little of the additional money paid by Western consumers for Fairtrade certified chocolate. They are left in the dark about world market prices by the Fairtrade cooperatives meant to inform them of such things. For many, the membership fees they must pay to participate outpace the premiums they can earn.

In Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, Fairtrade has become linked with the “cocoa mafia” and the historically corrupt state Cocoa Board, respectively. When FAIR team member Selay Kouassi first attemped to report that story, he was threatened and eventually forced to go into hiding. All this suggests that Fairtrade is not just ineffective; rather, it has been subjected to and complicated by the realities of the post-colonial African economy, namely elite dominance and the inability of the state to fully establish a legitimate monopoly on violence.

But the report’s most damning finding is that, of everyone involved with the Fairtrade program, Fairtrade itself walks away with most of the money. In the Netherlands, for example, for each chocolate bar sold for $2.50, Fairtrade earns about six cents of the fair trade premium. West African cocoa farmers, on the other hand, earn only 2.5 cents. Over the course of 2009, this meant Fairtrade earned $520,000 from chocolate sales in the Netherlands, while the coffee growers themselves earned only $218,750. This is obviously deeply problematic, and though FAIR’s study focused only on cocoa, and only on Max Havelaar – the Dutch incarnation of Fairtrade – its account is another piece of evidence in a case increasingly stacked against Fairtrade.

Why would FAIR’s Selay Kouassi face threats if Fairtrade were not benefitting powerful actors above and beyond the farmers it was meant to help? What are we to do, as Western consumers, if Fairtrade is little more than a marketing gimmick? Contra the prevailing logic, should we avoid products marked with its logo? Are we being conned?

While aid often fails to achieve its goals, caught up in processes endemic to the post-colonial state, the same can be said of trade – at least in this case. But it’d be naïve to assume we’re talking about a unique case.

December 7, 2012

#GhanaDecides Playlist

Results of today’s parliamentary and presidential elections in Ghana are expected at the earliest by Sunday. (BTW, in areas where “the biometric verification machines did not work” voting has been extended till tomorrow.) Once you’ve checked out our elections preview (yes, our Dennis Laumann predicts incumbent President John Dramini Dramani Mahama will win a tight election), keep up with the elections through this bunch of sources: Al Jazeera English; the BBC (check out their Ghana elections FAQ); the crowdsourced (Ushahidi-clone) Ghana Votes 2012, which provides raw reports from polling stations; and the consortium of bloggers at Ghana Decides (though their site can take a while to load; they’re also posting videos on YouTube). Someone even created an exit poll on Google docs. If this is all too much work, just follow the #GhanaDecides hashtag on Twitter or befriend a Ghanaian on Facebook. Oh, and we have a playlist of fifteen songs (embedded above) to keep it Ghanaian.

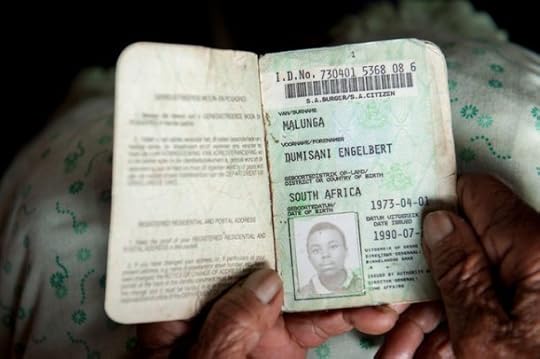

The New York Times reports on political violence in South Africa

The New York Times correspondent Lydia Polgreen’s report, earlier this week, on the murder of an African National Congress (ANC) candidate for a local town council in South Africa’s Kwazulu-Natal province in September this year has cast the spotlight on how local struggles for resources and power underpin the most recent spate of “political violence” in KwaZulu-Natal. The murdered candidate, Dumisani Malunga, was running as a ward councillor in Oshabeni, and was shot on his way back from a political meeting. Polgreen reports that in KwaZulu-Natal alone, “nearly 40 politicians have been killed since 2010 in battles over political posts.” Polgreen’s article focuses on intra-ANC political violence, but it is worth noting that there has been a significant increase in such killings since a new party, the National Freedom Party (NFP), broke away from the ANC’s rival Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in January 2011, claiming the lives of at least 30 IFP and NFP supporters and nearly 40 ANC officials.

Stakes are high in KwaZulu-Natal.

The ANC has less of a monopoly on control of local councils in the province than it does elsewhere in the country (with the exception of the Western Cape). As IFP members defected to the NFP led by Zanele Magwaza-Msibi (a former top IFP official), it quickly became clear that competition for local resources trumped serious ideological contestation. NFP members were targeted in the run-up to the May 2011 municipal elections when I was conducting historical research in communities around the Table Mountain area of KwaZulu-Natal. The NFP won 11% of the votes in KwaZulu-Natal, damaging the IFP’s already dwindling support and enabling the ANC to make significant gains. The new party split the IFP’s support base and the NFP later signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the ANC in at least 20 municipalities where there was no clear majority. But the coalition struggled at the microlocal level, where NFP leaders occasionally cooperated with IFP officials to overthrow ANC mayors. The most recent clashes erupted in KwaMashu near Ethekwini (Durban). The IFP retained control of KwaMashu after by-elections held there on Wednesday this week proceeded peacefully.

What media reports of these “political murders” in KwaZulu-Natal tend to overlook is the need to situate them in a larger historical context. Despite the New York Times’ claim to the contrary, South Africa’s transition was far from bloodless. Violence monitors conservatively estimate that nearly 12,000 people died between 1985 and 1996 in KwaZulu-Natal alone. This regional civil war, known in isiZulu as uDlame, left thousands more injured and displaced. Homes, cars, and other personal possessions were looted and destroyed. The international media labeled it “black-on-black” and “tribal” violence, especially in Gauteng where reports categorized the conflict as one between the Zulu ethnic nationalist IFP and the rest (Xhosa, Sotho, etc) under the ANC. While the most commonly cited explanation for the transition-era violence roots it in this struggle for political supremacy between the ANC and IFP, fueled by the apartheid state’s covert activities, there was often a disjuncture between the national political parties and local actors. From Table Mountain and Durban’s Molweni and Inanda areas to the East Rand townships, “political violence” was inseparable from conflict over the control of local resources, ranging from land and housing to taxi routes. And everybody involved in the conflict spoke Zulu. Some of these struggles, particularly those I studied in rural Table Mountain, were deeply influenced by the legacy of colonial and apartheid land, administration, and employment policies that created chiefs, boundary lines, and rural reserves.*

As apartheid gave way to democracy, many observers credited President Jacob Zuma (then first an ANC official and briefly as provincial government minister of the province) with brokering the cessation of violence in KwaZulu-Natal. It will be interesting to see whether or not Msholozi (as Zuma is popularly known) heeds the call to return as negotiator. Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini, loathe to address the persistence of staggering inequalities that foments the current competition for resources, recognizes the continued impact of tensions held over from transition-era conflicts. The Zulu king recently suggested the solution to the bloodshed lies in an umkhosi woswela, a ceremony to cleanse Zulu men of the lingering “evil spirits that breed violence.” President Zuma and King Zwelithini attended a similar reconciliation ceremony in November 2010 in Vulindlela, an area of Pietermaritzburg devastated by the wars of the 1990s.

While these rituals can be important to the healing of still deeply divided communities, the lack of political accountability, access to land, and decent jobs is likely to continue to spark vicious struggles like that which killed Dumisani Malunga. The connection between the contemporary political violence and material deprivation and inequality is undeniable; but these conflicts are not new and are deeply rooted in colonialism and apartheid.

By the way, much of contemporary historical work has overlooked this relatively recent painful era, but for those wanting to learn more about the transition-era violence one might start with Mario Krämer’s Violence as Routine; Gary Kynoch’s “Crime, Conflict and Politics in Transition-Era South Africa”; and Philip Bonner and Vusi Ndima’s “The Roots of Violence and Martial Zuluness on the East Rand” (in Zulu Identities). Not so good would be the work of Anthea Jeffery.

* Jill Kelly is assistant professor of history at Southern Methodist University.

“This is not Pantsula”

I got a treat when I was in Johannesburg recently. I was about to jump into a cab when this van pulls up and out piled these colorfully clad kids. With their exit came the loud blasting house sort of music; then the dance moves, taunting, shouting matches, some alcohol, and street fashion…but at the end of the day, it was about the dance. I was mesmerized to say the least. A quick enquiry informed me that the phenomenon I was witnessing is called “sbujwa” — apparently not a new sight in the city. It is described as “a dance that requires every muscle in your body to work in order to complete moves” plus lots of creativity. There are differing views as to its origin, as seen here and here. Wherever it might have originated from, it was a delight to watch:

I got a treat when I was in Johannesburg recently. I was about to jump into a cab when this van pulls up and out piled these colorfully clad kids. With their exit came the loud blasting house sort of music; then the dance moves, taunting, shouting matches, some alcohol, and street fashion…but at the end of the day, it was about the dance. I was mesmerized to say the least. A quick enquiry informed me that the phenomenon I was witnessing is called “sbujwa” — apparently not a new sight in the city. It is described as “a dance that requires every muscle in your body to work in order to complete moves” plus lots of creativity. There are differing views as to its origin, as seen here and here. Wherever it might have originated from, it was a delight to watch:

I found a short documentary on sbujwa on YouTube:

And here’s another example:

I’m hoping some “anthropologist” might be interested in researching and explaining this and other street dancing phenomenons in Johannesburg. You’ll find the rest of my photos here.

December 6, 2012

10 African films to watch out for, N°14

Documentary filmmakers are better at spreading the word about their new work on the web compared to fiction directors, or there’s just more documentary films being made. (Or I’m looking in the wrong places.) Here are ten more films to watch out for. First, four fiction features: A Menina dos Olhos Grandes (“The girl with the big eyes”) is based on a popular story from Cape Verde: a “creole girl” returns from Europe to her homeland due to the sudden death of her father where she will come up against an unfamiliar reality and ghosts of her past. Trailer above. (Also check this older trailer to get another feel of the film.)

Tourbillon à Bamako (“Swirl in Bamako”).

Tourbillon à Bamako (“Swirl in Bamako”).

Synopsis:

A wild chase in search of a lottery ticket through the streets of Bamako.

Film Details:

Country: Mali

Director: Dominique Philippe

Production: Babel Films

Cast: Chek Oumar Sidibé, Mama Koné, Fatoumata Coulibaly

The film’s Facebook page has a trailer.

A Lovers Call is a short film by Najma Nuriddin about Aasim, a young single Muslim man living in Washington DC who falls for a poet named Kala. The film is filed in the portfolio of Nsoroma Films, a US-based production house “of the African diaspora … dedicated to telling organic stories.” Here’s a trailer:

Elelwani is a new film by South African director Ntshavheni wa Luruli (whose film The Wooden Camera was awarded the Crystal Bear for Best Youth Feature at the Berlinale in 2004). Selling-line: “the world’s first Venda film”:

And six documentaries (made/in-the-making):

The Engagement Party in Harare is a 35mins documentary film by British/Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Piotrowska “about post-colonial identities at the Harare International Festival of the Arts in Zimbabwe.” The film features the HIFA organizers as well as Zimbabwean artists such as Raphael Chikukwa (photo left) and Tsitsi Dangaremba. No trailer yet.

The Engagement Party in Harare is a 35mins documentary film by British/Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Piotrowska “about post-colonial identities at the Harare International Festival of the Arts in Zimbabwe.” The film features the HIFA organizers as well as Zimbabwean artists such as Raphael Chikukwa (photo left) and Tsitsi Dangaremba. No trailer yet. Rwagasore: Life, Struggle, Hope is a film by directors Justine Bitagoye and Pascal Capitolin and producer Johan Deflander about Burundi’s struggle hero Prince Louis Rwagasore who became the country’s first Prime Minister, and was murdered a few days after the formation of his government, on October 13, 1961. According to the film’s website “the film [was] shown during the [2012] cinquentenaire festivities on July 1st at the Burundi embassy in Moscow. This mainly for the Burundese diaspora in Russia.”

Rwagasore: Life, Struggle, Hope is a film by directors Justine Bitagoye and Pascal Capitolin and producer Johan Deflander about Burundi’s struggle hero Prince Louis Rwagasore who became the country’s first Prime Minister, and was murdered a few days after the formation of his government, on October 13, 1961. According to the film’s website “the film [was] shown during the [2012] cinquentenaire festivities on July 1st at the Burundi embassy in Moscow. This mainly for the Burundese diaspora in Russia.”

Here’s a first trailer for I Sing the Desert Electric, a short film about electronic based musical phenomena occurring from Mauritania to Northern Nigeria. Cue sahelsounds:

Underground/On the Surface revolves around a new underground musical genre known as Mahraganat Shaabi which despite being rejected by the mainstream has become very popular with the youth in the streets of Cairo:

(Related: don’t miss Afropop Worldwide’s recent feature on Cairo’s musical “underground”.)

Mother of the Unborn is Nadine Salib’s first feature length documentary and looks at the challenges faced by Egyptian women unable to conceive, and subsequently face rejection by their families and stigmatization by their communities. The film tells stories of several childless women who navigate their world of rural Egyptian myths, legends, habits and traditions surrounding childbearing and infertility:

And in 1962: De l’Algérie française à l’Algérie algérienne (“From French Algeria to Algerian Algeria”) Malek Bensmaïl and Marie Colonna revisit French and Algerians’ moods and expectations during the seven weeks that separated the official France-Algeria cease-fire on March 19, 1962 from the first elections for the National Algerian Assembly. The film’s website has a trailer.

And in 1962: De l’Algérie française à l’Algérie algérienne (“From French Algeria to Algerian Algeria”) Malek Bensmaïl and Marie Colonna revisit French and Algerians’ moods and expectations during the seven weeks that separated the official France-Algeria cease-fire on March 19, 1962 from the first elections for the National Algerian Assembly. The film’s website has a trailer.

Foreign correspondents and false notes

Two things I’ve learned about the popular press in the last few months: you don’t get to pick your own headline, and you don’t want anyone thinking that the inevitable picture of the guy with a machine gun is the author photo (not the one above, although strictly speaking, if his face is hidden, it might be hard to prove he’s not you). On the other hand, reporters writing in places like The Globe and Mail do get to write sentences in which they express astonishment at the presence of “mud huts,” goats and chickens on military bases, and at the sewage flowing in the roads of the garrison town of Kati. (Note to journalist: I really doubt that was raw sewage, but wuluwuluji. Ask someone.)

Two things I’ve learned about the popular press in the last few months: you don’t get to pick your own headline, and you don’t want anyone thinking that the inevitable picture of the guy with a machine gun is the author photo (not the one above, although strictly speaking, if his face is hidden, it might be hard to prove he’s not you). On the other hand, reporters writing in places like The Globe and Mail do get to write sentences in which they express astonishment at the presence of “mud huts,” goats and chickens on military bases, and at the sewage flowing in the roads of the garrison town of Kati. (Note to journalist: I really doubt that was raw sewage, but wuluwuluji. Ask someone.)

Local color and snide observations aside, anyone who can keep shining light on the intertwined dangers of an undisciplined army and the bugbear of ethnic militias—as the author of “the West’s Latest Afghanistan” does, and as Tamasin Ford and Bonnie Allen have done—is making a contribution.

So is it the editors who are ginning up and cashing in bad analogies at will? Who wants us to believe that Mali is like Afghanistan?

This is not a new trope: the BBC peddled the same comparison back in June; so did NPR two months later; PressTV, aka “the Iranian CNN,” also ran with it; and more recently, even Immanuel Wallerstein jumped on it as a headline for a blog post on his website. We’re told Mali is a –stan (Africanistan? Sahelistan?), but as Andrew Lebovich and I have argued, it really isn’t. Those who make the analogy almost uniformly leave out what Mali and Afghanistan might actually hold in common—narco-trafficking and the possibility for the countries of the global North to cock the place up completely—in favor of more superficial similarities, like the guys who show up where the author photo is expected to be. Others want to tell us Mali’s like Somalia, a comparison that makes even less sense, unless you’re Africom Commander General Carter Ham. But General Ham means the comparison militarily. In Somalia, the U.S. got Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda do the hard fighting, at heavy cost to them—including attacks on civilians back home—but at little cost to the U.S. Nice solution for the Americans, but a little less appealing to the African neighbors, one would think. The point is that weak analogies taken out of context don’t help our understanding, and when journalists resort to them they often cloud up what’s worthwhile in the reporting itself.

Take it from another angle. If Mali’s great musical tradition can help interest outsiders in the country’s plight, that’s a good thing. These are tense and troubled times for musicians as for everyone else. Writing in the Washington Post, Sudarsan Raghavan gets at that nicely. Still, it’s more than a little jarring to see Tinariwen—vocal supporters of the rebellion that spawned this disaster—presented in a slide show as simple victims. The writer doesn’t get to pick the photos, but they do shape our understanding. A little context, please?

As Raghavan shows, many of Mali’s musicians are in a terrible bind. Even those who aren’t living in fear in the North or exile in the South are suffering from the crisis. In Gao, musicians are hiding, and one of Mali’s great composers and instrumentalists told me the other day that even in Bamako many musicians are afraid to perform for fear of attacks. None have happened, but a recent story in the Malian press about tens of Islamists infiltrating Bamako stoked fears they might, along with a joke from a Malian wag about them joining the tens of thousands who live there already. Not funny at all is a series of kidnappings and arbitrary arrests carried out by the former junta. The arrest of two al Jazeera journalists provoked a justifiable reaction from the hard-working Mohamed Keita at the Committee to Protect Journalists, but soldiers have also hauled off prominent Malian business people in recent weeks. This has also got people on edge, and everything points to a long and grinding period of anxious waiting.

Foreign journalists—and yes, there are some good ones working in West Africa—would do well to get their heads around Mali’s crisis, because all signs are that it will be around for a while. More on that later. It looks like there’s plenty of time.

Zulu Metrosexuals

Lately, we’ve been hearing a lot about “Black Dandies” and the presence of new academic identities in US institutions. But anyone hear about Zulu Metrosexuals, and the ways in which the Zulu—men in particular—have similarly used dress to expand definitions of “Zuluness,” playfully unsettling colonial constructions and modern pressures alike? At the recent Distance and Desire symposium at NYU (that’s a link to my previous post on the symposium), my interest was piqued by one of the speakers, Hlonipha Mokoena describing the manner in which Zulu identity was formulated—via the aid of 19th century colonial-era photography, as well as imagined depictions of Shaka and his warriors.

Lately, we’ve been hearing a lot about “Black Dandies” and the presence of new academic identities in US institutions. But anyone hear about Zulu Metrosexuals, and the ways in which the Zulu—men in particular—have similarly used dress to expand definitions of “Zuluness,” playfully unsettling colonial constructions and modern pressures alike? At the recent Distance and Desire symposium at NYU (that’s a link to my previous post on the symposium), my interest was piqued by one of the speakers, Hlonipha Mokoena describing the manner in which Zulu identity was formulated—via the aid of 19th century colonial-era photography, as well as imagined depictions of Shaka and his warriors.

Mokoena, who teaches anthropology at Columbia University, points out that despite the plethora of romantic pictures of Shaka, intended to preserve and recreate the romantic primitive, the only thing we know about him to be true is a fragment of his costume: the crane feather that topped his head, adding to his legendary height. The rest is pure conjecture and fantasy. His unknowability meant that he became a “cipher,” Mokoena stated, whose finery blinded Europeans, who couldn’t see past the finesse of Shaka’s costume to note anything about his character, political strategy, or psychology. In turn, twentieth century historians, too, have been guided by these received notions of Shaka, who ignore the fact that Shaka himself was engaged in the process of self-invention—in the same way powerful, self-fashioning, subject-sacrificing rulers do, like Elizabeth I, her father, Henry VIII in England, or Emperor Asoka, in the vast swathe of land around Orissa in north eastern India.

But never mind Shaka—how does the image of the Zulu, in general, enter the consciousness of the global imaginary? Photography works on the premise of presences and even greater absences, while often denying those absences. What’s missing in the production of photographs with Zulu subjects? The manufacturing hand of the photographer in constructing these embodiments of Zuluness, as performed and posed by European image-makers who are themselves informed by their European settler/tourist audiences’ expectations of Africa in general and Zuluness in particular. These images maintain the African as a static entity, aiding useful colonial notions of black Africa as a place that contacted no one, borrowed nothing, shared ideas with no others: such notions helped encourage separations that later developed into apartheid.

No doubt, the Zulu captured Europeans’ attention: the archive contains a plethora of photographs and postcards—sent by visiting Europeans to their friends. In addition to the chiefs and warriors, there were Zulu “belles,” brides, and mothers carrying the requisite babies on slings (photographed in profile, in order to highlight, for the European audience, this particular method of keeping a child close to the body). There are no names or differences in identity permitted: the people pictured are framed by the photographer’s or postcard maker’s captions, typified by being placed in categories, branded before that became a thing to do on purpose.

Whatever we picture of when we think “Zulu” is conjured up by the same machinery of calculating colonial crazy that constructed their colonised subjects as representatives of the anteriority of capitalist modernity. Remember Oprah Winfrey’s claims about being Zulu? She should realise that for every card-carrying romantic warrior-type invented by missionaries’, explorers’, and settlers’ narratives—from North America (Apaches and the Sioux) to South Asia (Sikhs in the north west, and the Coorgs in the south) to Africa (Maasai, Nuba, and of course, the Zulu)—there’s an accompanying fear of the over-sexualised destructive native who wasn’t too well-endowed in the intellectual arena—and thus, had to be contained because of his proclivity towards marauding and raping. (Hilariously, the British, French et al. didn’t see their own marauding, raping generals and armies in the same light; and judging by the rhetoric surrounding the Global War on Terror and the Muslim Other, still don’t.)

Mokoena says that historically, the Zulu came into being under Shaka (there had been no other “king” of the Zulu before him); it is necessary to begin theorising about being Zulu as an encounter with “pictorial fantasies,” endless documentaries (often inaccurate and racist) and “historical” re-enactments on film and television mini-series. What it means to be Zulu in the twenty-first century is a kaleidoscope of refractions and reflections, informed by performances of performances.

She herself has a commanding sartorial presence—right down to the Modernist-inspired brooches, earrings and impeccably tailored suits. No wonder Mokoena is beginning a research project on the meaning and symbolism of clothing in nineteenth-century colonial Natal:

The availability and desirability of clothing is often associated with the arrival of missionaries who depicted clothing as the antithesis and an antidote to the ‘adornment’ associated with indigenous cultures. My research focuses on how nineteenth-century Africans made sartorial choices that blurred this line between clothing and adornment and how these choices were captured in paintings and photographs.

Post-Shaka, King Cetshwayo kaMpande (Shaka’ nephew, and the first African King to travel to England to meet Queen Victoria, on his own terms), Mokoena points out, was “well aware that clothing bestows advantage”: during his trip to England, his stately figure was covered not in beads and skin, but in a fine woollen great coat. The English didn’t have to take him on tours of the woollen districts in order to get him to comprehend the “value of clothing,” as, apparently, there is a record of them trying to do. One notices that Cetshwayo was topped not only by his proud stature, but his headring, which he maintained: heavy is the head that wears the crown, remembers the contemporary viewer of his visage. And like any modern self-fashioner (and Vogue.com’s style advisors), he knew exactly what ‘ethnic’ detail he should maintain, without looking out-dated, ‘too-much’ or, god forbid, weak and out of place. Instead, he signals his difference, and différance: his right—and royal ability to—to defer and to differ.

Post-Shaka, King Cetshwayo kaMpande (Shaka’ nephew, and the first African King to travel to England to meet Queen Victoria, on his own terms), Mokoena points out, was “well aware that clothing bestows advantage”: during his trip to England, his stately figure was covered not in beads and skin, but in a fine woollen great coat. The English didn’t have to take him on tours of the woollen districts in order to get him to comprehend the “value of clothing,” as, apparently, there is a record of them trying to do. One notices that Cetshwayo was topped not only by his proud stature, but his headring, which he maintained: heavy is the head that wears the crown, remembers the contemporary viewer of his visage. And like any modern self-fashioner (and Vogue.com’s style advisors), he knew exactly what ‘ethnic’ detail he should maintain, without looking out-dated, ‘too-much’ or, god forbid, weak and out of place. Instead, he signals his difference, and différance: his right—and royal ability to—to defer and to differ.

Not everyone appreciated the power of self-fashioning. In The Rebel, Albert Camus contended,

The dandy creates his own unity by aesthetic means. But it is an aesthetic of negation…Profligate, like all people without a rule of life, he is only coherent as an actor. But an actor implies a public; the dandy can only play a part by setting himself up in opposition. He can only be sure of his own existence by finding it in the expression of others’ faces…The dandy, therefore, is always compelled to astonish…Perpetually incomplete, always on the fringe of things, he compels others to create him, while denying their values. He plays at life because he is unable to live it.

Is that true for the self-aware as Cetshwayo? Or his fellow Zulu, bricoleurs who adopted and adapted, as any people do upon contact, creating pleasing assemblages like any London dandy of the same time period? I doubt that the archival images of young men playing with style are really doing it to “astonish” the European; rather, they seem to be doing it for each other. We forget to note that looking at each other was more important than the presence of the colonial gaze. We also fail to see the dandy in them, because we are trained to look for the native, that Zulu in our imaginary. We erase the presence of self-fashioning already evident in these photographs, overlooking the ways in which Zulu men and women have charted the sartorial traditions that captured their imaginations. These conversations with difference made uneasy entries into their daily repertoire.

Thus was born what Mokoena calls the “Zulu metrosexual,” long before young men in New York put on ironic brainy spectacles and sported tight re-constructed versions of their grandfathers’ stovepipes to display their slim legs, and their ability to be plugged into powerful circuits of consumption (here, consuming clothing and style communicates access, rather than food consumption—which, in the West, is too abundant to serve as a display-vehicle of power). Mokoena is a generous enough scholar to trace the provenance of the term “Zulu metrosexual”: while at a conference in Durban, she heard students from the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal using it as a translation of the Zulu descriptor igeza lensizwa (“beautiful young man”). In particular, Simphiwe Ngwane’s Honours thesis, “From igeza lensizwa to a black flâneur: South African black masculinity in transition” (University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2012) explored the idea.*

Where can the American and European spot this Zulu metrosexual? He’s unrecognizable if you’re looking for feathers and plastic beads. He’s busy contending for space with the monolithic hand of Zuluness as constructed by Zuma et al., who’s made things difficult for Zuluness quite a bit, going whole hog with prolific, irresponsible sexual choices (not that erstwhile National Party leaders from the apartheid era didn’t have many a bizarre retinue of sexual skeletons in their collective closet).

Don’t be mistaken: clothing and style are not the only cynosure of the Zulu Metrosexual’s ambitions; it is simply a reflection of the ability of the modern subject to be playful, aware, and mobile. These are things that often make the European (and American) worry—if the ‘natives’ don’t remain fixed, they become dangerously ‘slippery’; and the ‘Westerner’ wouldn’t have the corner on modern subjectivity cornered. But if you are man enough, what you’ll see are young people making self-directed, self-conscious choices about adornment, traversing through time periods and locations, mapping visual and intellectual routes. These fine young men don’t look too weighted down by the weight of the archive, or the proliferation in contemporary media of restrictive versions of what they should be. Instead, they look like they are having a whole lot of fun reaching for something: imagined, aesthetic geographies, displayed on the shifting gallery of the body.

* Also see: Mxolisi Mchunu’s chapter, ”A Modern Coming of Age: Zulu Manhood, Domestic Work and the ‘Kitchen Suit’” (p. 573-582) in Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, edited by Benedict Carton, John Laband, and Jabulani Sithole. Mokoena’s book on the Zulu and kholwa intellectual Magema M. Fuze (the author of Abantu Abamnyama Lapa Bavela Ngakona (1922) / The Black People and Whence They Came (1979)) is titled Magema Fuze: The Making of a Kholwa Intellectual. (University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, 2011).

December 5, 2012

Literary Sudans: A Warscapes Retrospective

Francis Mading Deng, Leila Aboulela and Tarek Eltayeb.

Guest Post by Bhakti Shringarpure

In the past decade, not many places have been as over-represented or as under-understood than Sudan and the newly formed South Sudan. From a barrage of news articles to a flurry of op-eds, from millions of dollars spent on advertising and brand-management for Darfur activism to insipid, shallow visits from Hollywood celebrities to troubled areas, not a stone has been left unturned in the media hype that is called Sudan. This is not to say that there is nothing going on, but simply to posit that rarely does one see a well-rounded, comprehensive or non-ideological approach to the crises that have been transpiring there since the late eighties. In the face of the one-note depiction of Sudan merely as a place of war and atrocities, then, I spent much time over the past months putting together a Warscapes retrospective, “Literary Sudans”. The online retrospective is intended to highlight the two Sudans as sites of literature and culture.

I began by seeking out Leila Aboulela, one of the best known Sudanese writers working today. She was on board from the get-go and provided invaluable contacts and suggestions, especially for writers based in South Sudan. Over the course of a few months, David L. Lukudu, who had been previously published on Warscapes, spread the word about this project and I was flooded with submissions from writers from all over South Sudan who were eager to tell their version of the story and of the conflict. The original retrospective included poets and artists but it became untenable and we narrowed it down to fiction where Sudan emerges as an energetic and complex place filled with people leading lives that range from the ordinary to unique. New fiction that is not anchored in its literary history can feel very rootless.

Though it would be tough to go as far back as I would wish, I was glad to include an excerpt from Francis Mading Deng’s 1987 novel Cry of the Owl. Deng is currently South Sudan’s Ambassador to the UN, but his now forgotten novel was one of the first to explore the fragile mythology of identity politics that has torn the North and South apart. Tarek Eltayeb’s 1992 novel Cities Without Palms, originally written in Arabic, has also been excerpted here. Eltayeb’s trajectory is particularly cosmopolitan and his hero Hamza’s journeys from a small village in Sudan to Vienna is unique and perhaps representative of many in the Sudanese diaspora.

This special Warscapes issue spans narratives of return home from exile in the West to migratory journeys within Sudan and war’s impact on women and children. Leila Aboulela, author of Lyrics Alley and Minaret, has a new short story, Souvenir. Yassir visits his family in Khartoum after five years abroad. It is a bittersweet return, one replete with the epiphany that neither he nor his Scottish wife and daughter could ever fit into the space he once called home. Also touching upon the themes of exile is trilogist extraordinaire Jamal Mahjoub (Navigation of a Rainmaker, Wings of Dust, In the Hour of Signs) and he offers a sampling from his moody 2006 novel, The Drift Latitudes which is, in his own words, “a position of uncertainty” and “a sense of belonging to more than one country.”

This special Warscapes issue spans narratives of return home from exile in the West to migratory journeys within Sudan and war’s impact on women and children. Leila Aboulela, author of Lyrics Alley and Minaret, has a new short story, Souvenir. Yassir visits his family in Khartoum after five years abroad. It is a bittersweet return, one replete with the epiphany that neither he nor his Scottish wife and daughter could ever fit into the space he once called home. Also touching upon the themes of exile is trilogist extraordinaire Jamal Mahjoub (Navigation of a Rainmaker, Wings of Dust, In the Hour of Signs) and he offers a sampling from his moody 2006 novel, The Drift Latitudes which is, in his own words, “a position of uncertainty” and “a sense of belonging to more than one country.”

Two young new voices from South Sudan offer suspenseful and filmic short stories. Edward Eremugo Luka, a practicing doctor in Juba, gives us Casualty. In this deceptively simple tale, young kids stumble upon relics from an old civil war as they play in the field, with disastrous consequences. And in Seiko Five by David L. Lukudu, a spirited woman, Fatna, makes a living in an Omdurman slum by brewing and selling some of the best liquor in town. The tension becomes palpable as the corrupt and brutish cops turn her place upside down for evidence of illegal activity.

Mahmood Mamdani writes that, “History is important because it permeates memory and animates it, shaping the assumptions that we take for granted as we act in the present.” Though the two Sudans occupy a space that has been heavily politicized, their culture and arts have not had much breathing space precisely because of this politicization. Literature might help to arrive at a better understanding of the place. So let’s enjoy this rich outpouring of stories, characters and imaginations from the two Sudans.

* Bhakti Shringarpure is the editor of Warscapes.

Ghana’s elections: Back to the future

The critically-acclaimed documentary “An African Election” is an excellent primer for Friday’s elections in the small, but pivotal West African nation of Ghana. Directed by Jarreth Merz, the film chronicles the final month of campaigning in Ghana’s December 2008 presidential elections which led to a hotly-contested nation-wide run-off later that month, followed by a cliff-hanger vote in a single rural constituency one week later. The film seems to focus on the specters of violence, intimidation, and fraud that hung over the elections like dark clouds, but Ghana’s reputation as a relatively stable, peaceful and democratic nation — within a region characterized by coups, rebellions, and fraudulent polls — emerged intact. Though much has changed in Ghana over the past four years, including the start of off-shore oil drilling, most of the same issues and personalities that feature in the 2008 elections dominate this week’s vote, too.

The 89-minute documentary is largely comprised of contrasting scenes of massive campaign rallies — during which the two main presidential candidates offer endless lists of locale-specific promises met with thunderous approval by throngs of supporters — and analytical commentary by mostly partisan scholarly “experts” and political leaders.

The film succeeds in portraying Ghana as a lively if imperfect democracy where ordinary voters freely share their strong opinions on camera. While the filmmakers briefly provide some historical context, particularly on Ghana’s first decade after independence in 1957, more attention to the ethnic rivalries, regional differences, and ideological divides in Ghana would help viewers better understand the election’s dynamics.

The foremost presence in the film, even more so than the two presidential candidates themselves, is J.J. Rawlings, Ghana’s larger-than-life former long-time leader. Dismissed by his mainly reactionary opponents as an authoritarian demagogue who came to power through “the barrel of the gun,” he is hugely popular amongst ordinary Ghanaians (as evident in many scenes in the documentary) and widely credited with transforming Ghana into the success story it is today.

When he came to power during the 31st December Revolution of 1981, Rawlings represented a new kind of Ghanaian ruler — a member of a minority ethnic group, not connected to any of the country’s elite families, and willing to get his hands dirty participating in voluntary labor projects. He presided over essential economic and political reforms, first as a revolutionary leader in the 1980s, then as a democratically-elected president and founder of the social democratic National Democratic Congress (NDC) in the 1990s.

In the film, we watch Rawlings stride triumphantly onto campaign rally platforms in far-flung towns, drive his own car through the busy streets of Ghana’s capital of Accra while offering a critique of western imperialism, and receive international election observers at his private residence where he issues dire warnings about the incumbent government’s attempts to steal the election.

In 1998, at the end of his constitutional two-term limit, Rawlings handed over power to John Kufuor, then leader of the opposition right-wing New Patriotic Party. The example Rawlings set – giving up power after nearly 20 years and then staying in the country as his opponents took over — was admired by Africans across the continent who also marveled at Ghana’s economic and political strides during his tenure.

Kufuor’s administration was generally unremarkable, except that it was rife with corruption and ethnic favoritism and very closely allied with the U.S. administration of George W. Bush. The elections documented in the film come at the end of Kufuor’s two terms and while he barely makes an appearance on screen, Kufuor played a key role in maintaining peace during the fervent final days of the extended campaign.

The election pitted the NPP candidate Nana Akufo-Addo, who served as Attorney General and Foreign Minister in Kufuor’s administration, against the NDC’s John Ata-Mills, Rawlings’s former Vice President and a law professor.

The elections, like all of Ghana’s elections every four years, were a re-match between the two dominant parties who claim divergent political lineages and constituencies. The NPP has always been an elitist party of reaction — opposed to Ghana’s founding President Kwame Nkrumah’s demand for independence from British colonial rule in the 1950s, for example — with electoral support almost exclusively limited to the Akan ethnic group. In contrast, the NDC is a national party, drawing support from within and outside the majority Akan areas, and encompassing adherents of the Nkurmah and Rawlings leftist traditions.

When neither candidate received the constitutionally-required “50 + 1” percent in the polls, a run-off election was called by Dr. Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, the extraordinarily serene and composed Chairman of Ghana’s Electoral Commission, another star of the documentary.

After another inconclusive result – and viewers are treated to spellbinding scenes in the election commission’s “war room” where representatives of the two parties trade accusations and threats – Afari-Gyan orders a re-vote in the Tain constituency where it was determined there had been problems with ballot distribution.

To say that all eyes were on Tain is an understatement, as the Ghanaian media descended on the remote district where the NDC had an electoral advantage. After the special vote, Afari-Gyan declared Mills the winner by less than 1% and NDC supporters hit the streets in ebullient celebration.

Behind the scenes, and the film suggests this, sources claim Akufo-Addo refused to accept the result. It was then that his former boss, outgoing President Kufuor, convinced the NPP flagbearer to gracefully accept defeat and concede to the Mills. Thus, even his opponents conceded that Kufuor emerged as a true statesman at the end of his tenure, if only because he was fearful his party’s notorious “macho men,” taking their cue from Akufo-Addo, would incite violence and thus tarnish Ghana’s image.

Remarkably, this week’s elections were supposed to be an exact re-match of the 2008 race, pitting Mills against Akufo-Addo once again, but the Ghanaian president tragically died in July. Mills’s Vice President, John Dramini Mahama, who was sworn into office as president hours after Mills’s death, now faces Akufo-Addo in Friday’s polls.

Like the recent American elections, the Ghanaian media claims the vote will be too close to call, but NDC supporters are hopeful Mahama will prevail since support is particularly strong in rural areas that have benefited from aggressive development programs over the past four years. Polling by neutral bodies suggest Mahama has a slide lead over Akufo-Addo.

In many ways, Akufo-Addo is the Mitt Romney of Ghana: he has been running for president for years, his support base is very limited, and he represents the interests of the wealthy.

Regardless of political affiliation, Ghanaians are hoping for a “one-touch” result, meaning one candidate wins outright this Friday thus avoiding a run-off, and most importantly, a peaceful election.

To get a crash course in Ghana’s politics, and to appreciate why Ghanaians want to avoid a repeat of the 2008 elections, “An African Election” certainly is an entertaining and informative documentary.

* Dennis Laumann is associate professor of history at the University of Memphis.

The “legacy” of Mwai Kibaki

We know journalists will soon begin to obsess over what is the legacy of Mwai Kibaki, Kenya’s 3rd President since Independence. Kibaki has to stand down next March (when elections are scheduled in Kenya) after two terms in charge (including a disputed December 2007 re-election). It’s hard to make sense of the politics around Kibaki’s “legacy.” Legacy truncates. Legacy is very often mis-remembering. I mean, anyone who’s ever gone to a retirement party can attest to this. Retirement parties also remind me of funerals: eulogies remain the best lies we tell (ourselves) about ourselves. Legacy is the same, so that Rosa Parks is not months and months of community organizing and preparedness, and broad base movement building, and political action, and coordinated effort and sacrifice, but rather that lady who refused to surrender her seat. This is legacy, which is why I’m not certain it is important.

Kibaki’s legacy is that he represents schooled/rational violence. Kibaki is our London School of Economics guy. Unlike Daniel arap Moi the unschooled dictator, Kibaki is a dependable neoliberal technocrat. His legacy is clear: be it the disarticulated neoliberal expansion that he is praised for, or the normalization of state violence through the “rational” deployment internally of the military and the police to subdue and torture for the peace. And sure, Kibaki’s legacy can be reduced to post-election violence, even as I am uncomfortable with the singularity of post-election violence.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers