Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1514

November 15, 2013

The Cadillac Tax: A Game Changer for U.S. Health Care

While the current debates over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) revolve around the individual mandate and the exchanges, one of the most important features of the law doesn’t take effect until 2018: the so-called Cadillac tax. This tax represents a key public policy innovation that is a rare win-win: it will hold down health care costs while raising substantial tax revenues.

The ACA is fundamentally a compromise between those who would rely on our existing private insurance system and those who would implement broader public sector involvement. The compromise resulted in major financial investments and regulatory interventions in the market for individually purchased insurance, with more modest interventions in the much larger employer-sponsored insurance sector. As a result, in the near term, the ACA will have minimal impact on employer-sponsored insurance (ESI).

My estimates, as well as those of the Congressional Budget Office, suggest that the effect on employer-sponsored insurance will be relatively modest: the number of individuals with employer-sponsored insurance will decline by about 3%. This modest impact reflects fairly sizable dropping of insurance among smaller firms, offset by large influxes of individuals in large firms who were previously eligible for insurance but who now take it up because of the mandate. While this is a nontrivial effect, it is fairly small relative to the 18% decline in employer-sponsored insurance we have seen over the past 15 years. The CBO also preliminarily estimated that premiums on average will not significantly change for either small or large firms; that was also my assessment for small firms in states I have studied, as well.

In the long run, cost controls included in the ACA will have a more fundamental impact on ESI. The primary mechanism for doing so will be the Cadillac tax.

Under current U.S. tax law, workers are taxed on their compensation that comes in the form of wages, but not on their compensation in the form of health insurance. So if MIT pays me $1,000 in wages, I take home less than $600; but if MIT pays me in health insurance, I get the full $1000 in insurance. Economists call this a “tax subsidy” because it is equivalent to the government’s giving me a check for 40% of the costs of my insurance; either way insurance is 40% cheaper than wages because wages are taxed and insurance is not.

This tax subsidy to ESI has three costs. First, it is incredibly expensive: the annual cost of this tax break is about $250 billion, or about twice what it would cost to cover every uninsured American with insurance. Second, it is regressive: the richer you are, the higher your tax rate, so the bigger the tax break you are getting. Third, it is inefficient: since individuals are buying health insurance with tax-subsidized dollars, they buy too much insurance, which in turn leads to too much health care. Economists have for years pointed out that this tax break is a major driver of high and rising health care costs in the United States.

The ideal solution to this problem would to treat health insurance like wages, addressing all three of these issues. One alternative that has frequently been proposed is a “cap” on the tax break, so that health insurance is only taxed like wages above a certain threshold. The Cadillac tax is an indirect means of accomplishing this same policy goal. Insurers will pay an excise tax at 40%, approximately equal to the top income tax rate, on policies above a certain threshold (which should amount to about the top 10% most expensive insurance plans). Insurers will quickly pass this cost on to consumers, and it will serve to counteract the existing tax break – so effectively this operates in a similar way to just ending the tax break itself.

The Cadillac tax begins in 2018 and will affect only a minority of firms. But over time the tax threshold is indexed at the overall rate of price inflation, which is typically well below health premium inflation. As a result, more and more firms will be subject to this tax. The tax will lower the rate of health care spending growth and substantially reduce employer health insurance spending. At the same time, it will raise substantial new revenues for a cash-strapped federal government. Indeed, the rising Cadillac tax revenues are a major reason why the ACA overall is greatly deficit reducing over the long run.

Usually, when discussing new sources of revenue, society faces a tradeoff: higher taxes mean more distortion to economic activity. Slowly removing the tax subsidy to employer-sponsored insurance presents a rare win-win solution that doesn’t involve this tradeoff: revenues go up and economic efficiency improves because we no longer subsidize the purchase of expensive health insurance.

The Cadillac tax is not ideal. A flat 40% tax does not precisely offset the tax subsidy to insurance for individuals who have different tax rates, so a better solution would be to simply treat health insurance like wages, including health insurance spending on the W-2 and taxing it as earnings. My recent estimates for the Bipartisan Policy Committee suggest that replacing the Cadillac tax with a policy that included in taxable income the top 20% of employer health insurance spending would raise more than $250 billion over a decade. But the Cadillac tax remains better than the alternative, a continuation of our existing open-ended insurance subsidy.

The ACA includes other provisions that should further help control the costs of employer insurance: the insurance exchanges should introduce competition into insurance markets that will bring down premiums; research on comparative effectiveness will help us assess the lowest-cost options for treating disease; and alternative reimbursement structures such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) will coordinate care across providers and lower costs as a result. It is difficult to confidently project the impact of these changes on costs, but taken together they represent the best collective thinking on how to “bend the cost curve.”

When all is said and done, the ACA will really not matter much in the near term for the majority of Americans who have ESI. In the longer term, it can benefit that majority through combatting the insatiable rise of health care costs.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Fix the Handful of U.S. Hospitals Responsible for Out–of–Control Costs

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

Countries with Better English Have Better Economies

Billions of people around the globe are desperately trying to learn English—not simply for self-improvement, but as an economic necessity. It’s easy to take for granted being born in a country where people speak the lingua franca of global business, but for people in emerging economies such as China, Russia, and Brazil, where English is not the official language, good English is a critical tool, which people rightly believe will help them tap into new opportunities at home and abroad.

Why should global business leaders care about people learning English in other parts of the world?

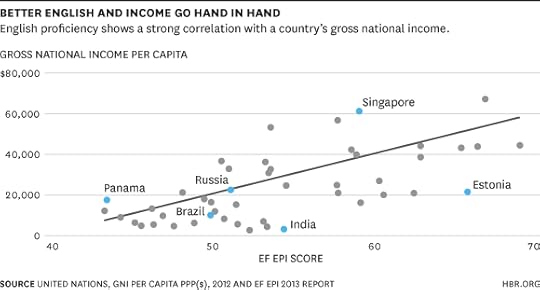

Research shows a direct correlation between the English skills of a population and the economic performance of the country. Indicators like gross national income (GNI) and GDP go up. In our latest edition of the EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI), the largest ranking of English skills by country, we found that in almost every one of the 60 countries and territories surveyed, a rise in English proficiency was connected with a rise in per capita income. And on an individual level, recruiters and HR managers around the world report that job seekers with exceptional English compared to their country’s level earned 30-50% percent higher salaries.

The interaction between English proficiency and gross national income per capita is a virtuous cycle, with improving English skills driving up salaries, which in turn give governments and individuals more money to invest in language training. On a micro level, improved English skills allow individuals to apply for better jobs and raise their standards of living.

This is one explanation for why Northern European countries are always out front in the EF EPI, with Sweden taking the top spot for the last two years. Given their small size and export-driven economies, the leaders of these nations understand that good English is a critical component of their continued economic success.

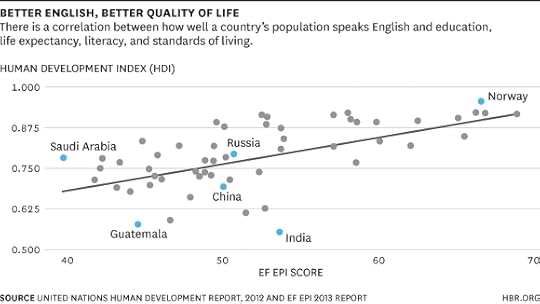

It’s not just income that improves either. So does the quality of life. We also found a correlation between English proficiency and the Human Development Index, a measure of education, life expectancy, literacy, and standards of living. As you can see in the chart below, there is a cutoff mark for that correlation. Low and very low proficiency countries display variable levels of development. However, no country of moderate or higher proficiency falls below “Very High Human Development” on the HDI.

For business leaders, knowing which countries are investing in and improving in English can give valuable insight into how a country fits into the global marketplace and how that might affect your company’s strategy. Here are just a few of the questions you might consider:

Which countries are aggressively improving their English proficiency in an effort to attract businesses like mine?

Where could poor English hinder the growth of emerging economies?

In which countries should I target my international recruitment efforts?

As we think about expanding globally, where will my existing, native English-speaking employees find it easiest to relocate?

Business leaders who understand which nations are positioning themselves for a smoother entry into the global marketplace will have a competitive advantage over those who don’t. Your company needs to know how the center of English language aptitude is shifting. Because knowing English is not just a luxury—it’s the sina qua non of global business today.

Job Candidates Should Be Less Risk Averse

Candidates like to employ a play-it-safe strategy during job interviews. They offer conservative answers. They avoid saying anything atypical. They let their credentials do the talking. But in this hyper-competitive market, a risk-averse approach may not be the way to go. When it comes down to it, hiring committees talk about what they remember most about a job candidate. Experience and credentials are important to them, of course. But so, too, are lasting impressions. So perhaps candidates should stop worrying about fitting in, and start trying to find ways to separate themselves from the pack.

November 14, 2013

Get a Dysfunctional Team Back on Track

Roger Schwarz, author of Smart Leaders, Smarter Teams, explains how to build trust and accountability on your team.

Does Your Company Actually Need Data Visualization?

Data visualization – and I hate to admit this, because I make my living from it – is not for everybody. My client work and research suggest that, loosely speaking, organizations selling ideas rather than products stand to benefit the most. Frankly, with few exceptions, if this doesn’t describe your organization, then don’t bother.

Data visualization can be expensive, especially if it involves large amounts of data and complex algorithms or deep interactive experiences. So how do you decide whether your company should invest in it? If you’re selling straightforward solutions to simple problems, data visualization is probably not worth the money. For example, consumer packaged goods firms Coca Cola and Nestle don’t need interactive graphics to explain their products, just as Playboy and Playgirl don’t need to educate the opposite sex much about their centerfolds. Such products more or less speak for themselves. (Now here’s the key caveat – sometimes product companies do have more complex and nuanced stories to tell, in which case they should be using visualization. For instance, I would love to see a data visualization explaining the environmental benefits of the Coca Cola’s PlantBottle sustainable packaging.)

On the other hand, if you’re selling a complex answer to a complex problem, you should be embracing data visualization with gusto. Non-governmental organizations, charitable and advocacy groups, and publishers have wisely jumped on board. Financial services companies have a myriad of offerings helping you see where your money is going, and companies like General Electric are devoting entire websites to visualize their data. Professional services firms are also hopping on board, offering online tools for digging into research results and making them meaningful.

Explaining a complex idea to an online audience requires a level of personalization, detail, nuance and openness that only an interactive visualization can provide. (Keep on charting, New York Times.) These organizations need to let their audience play with their data to make their findings more useful and convincing. That, of course, is the bottom line – such experiences have to give your users value, hopefully resulting in returned value to your organization in the form of sales and referrals.

Data visualization can produce big benefits, some of which are subtle yet powerful. One of the biggest benefits is personalization – e.g., enabling potential customers to estimate the value of a complex solution to their challenges. In 2010, BCG and the World Economic Forum wanted to demonstrate the economic benefits of employee wellness programs. They created an interactive graphic that lets executives calculate in 90 seconds roughly how much their companies could save by instituting such a program (based on the statistical data of other companies’ wellness programs). After filling in a few blanks – number of employees, how many are in the U.S., Europe and Asia-Pacific, and average regional salaries – the interactive graphic produces a series of 5-year projections for costs and potential savings from wellness intervention programs. After introducing it at the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos to great success, another partner company on the project continues to use it as a sales tool to model similar savings opportunities for entire cities.

Another way data visualization can help is by enlisting your audience to do the analysis you don’t have the time, manpower or editorial space to do yourself. Booz & Company has done this with mergers and acquisitions data. It published an interactive data visualization graphic that lets companies determine how easy (or hard) it is in eight major sectors to make acquisitions that enhance shareholder value. Published alongside an article in its thought leadership magazine strategy + business, this interactive graphic revealed insights and details on all 300+ deals (which couldn’t have been included in the article, of course). Booz & Company’s web analytics show that the viewers of this graphic stay longer on the website, engage more with the content, and come back to it over a longer time period than its average website viewer.

Companies like Booz & Company have studies with deep statistical data – more data than they have the time to chart, analyze and write about in their reports. Interactive graphics (when designed well) shift some of the data crunching and analysis to viewers who want a layer of depth that the company can’t provide through traditional publishing.

Data visualization can also help organizations whose products or services involve numerous steps to implement or many comparisons to consider that may differ from person to person. For example, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation recently sponsored a data visualization challenge, asking entrants to visualize hospital pricing data to bring transparency to a highly opaque market. An article summarizing this data would have to concentrate on statistical averages and give at most one or two examples. But in an interactive experience, you can click into any of the 300+ regions of the U.S. and look up pricing averages and per-hospital pricing for 100 conditions. In other words, you can quickly and easily browse over 165,000 rows of data to find out where is the best place to get a procedure done based on price, quality and experience at over 3,000 hospitals across the country.

Lastly, data visualization can also help organizations whose solutions go against conventional wisdom. Allowing your online viewers to plot the data lets them come up with the big “ahas” themselves. For instance, using the hospital pricing visualization above, you will find that pricing for most medical procedures in Boston, despite having among the top median incomes in the country and a reputation for some of the best hospitals as well, is actually well below average. While an article on the subject might have revealed this, unless Boston were the focus of the piece, odds are it would not have. Would an article reveal that Birmingham, Ala., has eight of the top 100 hospitals in the country that treat kidney infections, measured by overall quality scores from Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services? Perhaps not. And a Birmingham journalist, coming across this interactive, might naturally examine local pricing, discover this gem and write about it, spreading the word beyond the initial reach of the organization – all because of insights that would have otherwise been buried.

Companies selling complex solutions to complex problems should embrace the power of data visualization. Marketing and sales executives need to decide early whether their companies need it, because the learning curve is steep. And getting really good at it takes time, skill and money — for technology, training and high salaries to attract professionals with currently rare skills. For some companies, the investment is worth it. The rest should avoid the bandwagon altogether.

A Framework for Reducing Suffering in Health Care

Patients suffer — predictably and so obviously that they bring clichés to life. They wince with pain. They shudder with fear. They lose sleep because of anxiety and confusion. And, as they suffer, they turn to medicine for help. But medicine, increasingly, has not provided them with relief.

A century ago, little could be done to alter the course of disease, but clinicians understood suffering and their role in addressing it. They acknowledged it, they gave drugs to relieve pain, and they took the time to bear witness to what their patients were enduring. But in recent decades, spectacular medical progress has made many diseases treatable, and some even curable. Super-specialized physicians learned how to attack disease in various organs systems, and fatalism has gone out of fashion. Much good has resulted from that aggressiveness and the narrowed focus of clinicians — but patients’ suffering has been pushed from center stage into the background. Suffering still goes on, of course, but it is often overlooked. Perhaps it is overlooked because clinicians are so busy focusing on the technical details of care, or perhaps it is due to their uncertainty about how to respond. In fact, the profession so systematically avoids acknowledging suffering that medical journals don’t even use the term to describe a patient’s experience. Compliance rates may be said to “suffer,” but not patients. (See Thomas H. Lee’s essay “The Word that Shall Not Be Spoken” in the November 7, 2013 New England Journal of Medicine.)

The time has come to deconstruct suffering — break it down into meaningful categories that reflect the experience of patients and help caregivers identify opportunities to reduce it. Just as medical science has broken down patients’ clinical needs and created corresponding specialties, we propose a framework for major types of patient suffering so that health care providers can organize themselves to address suffering more effectively. Our hope is that this framework will show that suffering is neither too vast nor too vague to be measured, and that reducing suffering can thus serve as an overarching performance goal for providers.

We believe that a comprehensive approach to measuring and reducing suffering is not just an ethical imperative; it makes strategic sense for health care organizations. Those that can accurately categorize, measure, and mitigate their patients’ suffering most effectively will be rewarded with greater market share as well as the loyalty and retention of clinicians and other personnel. These personnel will take pride in and be motivated by the shared purpose of reducing suffering — more than is possible with financially driven goals alone. From our experience in direct patient care and measuring the patient experience, we believe that when you deconstruct suffering — that is, tease it apart to reveal underlying distinct and addressable components — instead of deconstructing patients by reducing them to the sum of a set of diseases or symptoms, you have a chance of leaving the patient whole, and delivering care that is truly patient-centered.

Types of Suffering

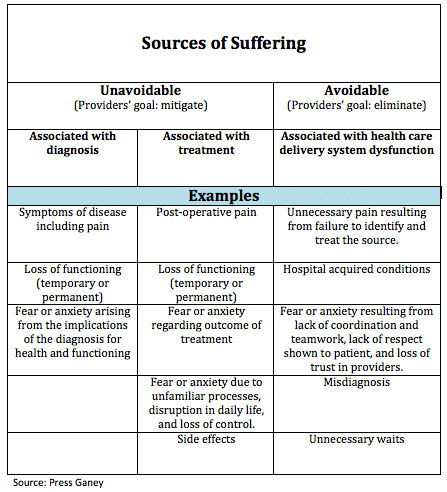

For any categorization framework to be useful, it must logically lead to distinct and effective responses. As the table below shows, we begin by dividing suffering into that which is unavoidable (e.g., pain caused by a disease) versus that which can be avoided (e.g., delays and confusion before or after the diagnosis is made). For suffering that is unavoidable, health care providers should organize themselves to anticipate, detect, and mitigate patients’ distress. For suffering that is avoidable, providers should perform these same roles, but also have a duty to measure and implement strategies that prevent the dysfunction that causes the suffering.

Unavoidable suffering

Unavoidable suffering is divided into two major types — suffering due to disease and suffering due to treatment. Before and after diagnosis, patients may have unavoidable suffering directly due to the specific condition they are experiencing. The disease or its complications may cause pain, other symptoms, or reduced function. Beyond such clinical issues, knowing their diagnosis often creates anxiety and fear, or a feeling of loss of control. It can challenge relationships and alter life plans.

Once patients begin to receive treatment for their illness or condition, they often experience unavoidable suffering arising from that treatment. Treatment may cause side effects, pain, discomfort, or loss of function whether it ultimately leads to recovery or only slows their decline. Additionally, patients may feel confused and anxious about having to navigate unfamiliar territory — both the physical structures and often arcane processes of the health care system. And treatment itself can be frightening.

Though these two types of suffering may be unavoidable, they are not untreatable — and, in fact, addressing them constitutes the agenda for many, if not most, interactions between patients and clinicians. In those interactions, physicians in particular tend to focus upon clinical suffering — reducing symptoms, treating the underlying illness and managing side effects. But all clinicians have additional opportunities to mitigate psychosocial suffering by providing information, orienting patients to the foreign environment, acknowledging and helping to reduce their anxiety and fears, showing compassion, and establishing trust.

Avoidable Suffering

The third category of suffering — the avoidable suffering that comes from dysfunction in health care delivery — is a type that patients do not anticipate but is often accepted by care givers as “part of life.” Preventable complications are one cause of such misery, but others are in fact much more prevalent. Patients endure waits for appointments, test results, and explanations, and even for their caregivers to communicate with one another about their care. Poor coordination leads to confusing communication with patients. Rocky transitions and hand-offs, or an apparent lack of concern about safety, erode patients’ trust. All of this can feed anxiety, frustration, and fear. That “special” patients, such as the family and friends of clinicians, often speed through the system without delays shows that such waits and dropped balls are indeed avoidable sources of suffering.

Measuring Suffering

The first step in reducing suffering must be to measure it. Today, our patient-experience data show that contrary to earlier assumptions, patients have always placed non-clinical offerings such as hospitality amenities or service interactions such as good food and parking in perspective; they matter somewhat, but not nearly as much as quality of care, control of pain, clarity of communication, emotional support, shared decision-making, and coordination of care. These factors are essential in building trust and confidence, which are in turn essential for reducing suffering. To be sure, soothing environments, exceptional courtesy and responsiveness, and even amenities designed to distract patients from their worries can help reduce suffering — but what has changed is the reliance on such tactics as the main focus for improving care. What has also changed is the understanding that defects in care do indeed exist. Before transparency, improvements in patient experience were often described as attempts to “delight” or “wow” patients because an implicit assumption had been made that care was already uniformly good. With the advent of publicly reported data, it’s now clear that significant opportunities exist to remedy deficits in care.

One fundamental and measurable issue that cuts across all three types of suffering is pain, the unavoidable cause of which may be the patient’s disease (e.g., cancer) or treatment (surgery). However, pain that is undetected (because clinicians did not ask) or under-treated it represents avoidable suffering. The pain itself is not the only form of suffering; if patients are not responded to with empathy and a sense of urgency, caregivers increase their anxiety and fear, while eroding their trust.

Another measurable source of avoidable suffering is patients’ experience of staff coordination. Patients’ experience of poor handoffs, lack of consistent knowledge of their treatment plan, conflicting opinions, or less than collegial behavior among their caregivers creates anxiety. In fact, patients’ evaluations of the degree to which staff worked together to care for them represent the strongest single correlate of their overall evaluations of the hospital (correlation with HCAHPS rating of the hospital is .90).

As insight into the importance of patients’ reports of their experience has grown, providers have realized that they need reliable data — and more of it, so they can analyze improvement opportunities at more granular levels. Thus, providers need enough data so they can segment analyses on the basis of patient characteristics and provider variables — down to the level of the individual physician. Segmenting by geography (i.e., patient care unit), shift or day of the week helps organizations pinpoint when and where dysfunction may be causing patients’ suffering. Ideally, patient evaluations of their experiences and other outcomes should be continuously collected for all patients as part of their care and to support organizational improvement.

Linking episodes of care, gathering real time assessments from patients and fully understanding the risk or resiliency patients bring to the care experience will transform our understanding of the suffering that exists and the suffering that we inflict through dysfunction. Future quality measures may expand on the concept of suffering to incorporate measures of disparity in suffering across patient populations.

Reducing Suffering

Reliably providing evidence-based clinical care is essential to reduce patients’ suffering — but it is not the only way. Indeed, excellent clinical care is “necessary but not sufficient”. As discussed, care givers must also build trust and relieve anxiety.

Skeptics may wonder if qualitative improvement in the control of anxiety, confusion, and fear is possible. In fact, such improvement is already well underway, as demonstrated by patient experience data collected from patients receiving care from hospitals, ambulatory groups, and other providers. This progress seems to be driven in particular by improvement in nurse communication, pain control, and care coordination. Nevertheless, these data also demonstrate marked variability among providers in these measures, and opportunities for improvement for all.

Ironically, this variability is a cause for optimism as it reveals that that improvement is possible. The patients who touch us, who become our favorites, or who, as friend or family have VIP status and for whom we therefore go far out of our way, help us to understand what addressing suffering means. The gap between how we treat them and how we treat everyone else demonstrates the distance we need to travel and the opportunities to improve.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Fix the Handful of U.S. Hospitals Responsible for Out–of–Control Costs

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

IT Can No Longer Afford to Ignore Its Users

The history of enterprise technology has been fairly unforgiving to the people intended to use it. For the past half-century, most information technology models propagated two unassailable truths: that enterprise technology was purchased by a select few, and the technology was bought for the company. As for the delight of the individuals using the technology itself? They’ll deal.

It was a clear, if inelegant approach. But it was an approach that worked for a period when information technology was relatively scarce, cumbersome, and often extraordinarily expensive. During these decades, IT organizations retained nearly complete control of the technology architecture, and with little to challenge them. Bob in Finance simply didn’t bring his own mainframe to work. Sure, end-user software would occasionally go viral (Visicalc, anyone?), but no matter how easy it was to buy a computer at your neighborhood CompUSA (R.I.P.), the complexity and cost of enterprise software ensured that the IT model remained enterprise-centric.

Fast forward to today, and several trends are upending the traditional IT approach. People who have been using computers since before they could walk are now entering the workplace by the millions, employees of all ages are bringing their own devices and software into the office, and cloud adoption is shifting computing workloads out of the enterprise’s data center.

New workers. New devices. No more servers. Usually a single inflection point is hard to grapple with. Today’s enterprises have three.

The old model is no longer sustainable. Work is changing, and IT needs to change along with it.

It used to be that the IT department’s job was to define and standardize on a set of systems, processes, architectures and technologies for the organization. But how can an enterprise standardize on a dimension like mobile that’s always one hardware cycle away from changing dramatically? Or how can an enterprise implement a mobile strategy leading with iPads, but continue to support software vendors that don’t play well with Apple?

Some call this “consumerization of IT”, but this descriptor mostly misses to the point. It’s not about consumer apps being used for work, and it’s not just about enterprise apps taking on more consumer-like characteristics.

The enterprise architecture of the future needs to invert traditional thinking. Instead of looking at the world as a series of systems, networks, and data schemas from an enterprise top-down view, start looking at the users’ needs first and expand outward from there. Geoffrey Moore describes the need for a “social contract” between IT and end-users, one that’s built on a foundation of fundamental principles: applications must run on any device, identity can extend anywhere, and data is always accessible.

In this new world, IT organizations focus on enabling productivity. User interfaces are no longer regarded indiscriminately, but weighed heavily. Control of information is no longer prioritized over making sure the right people can access it. CIOs who don’t empower their workforce become disempowered.

This is going to be a hard change to swallow for many IT groups, with new skills to learn, strategies to develop, and processes to implement. But there are many examples of it paying dividends. Ralph Lora, the CIO of Clorox, riffing off the antagonistic concept of “shadow IT,”, has implemented an approach he calls “Shallow IT.” This allows for the wide testing and nurturing of consumer-grade and adopted solutions in the enterprise, done in a calculated but flexible way, proving out all new enterprise apps to help power the $5.5B company. Eduardo Conrado is shifting Motorola Solutions toward User-centric IT, distinct from a traditional operationally focused view. Mike Kail, the CIO of Netflix, leads his organization by focusing on what IT can provide, instead of what IT can control.

And as the IT function evolves, technology vendors must keep pace to remain relevant. When decision-making power was concentrated at the top of an organization, software vendors reflected this reality by prioritizing features and functionality designed to be “bought” instead of “used.” But today, users and individuals have more influence over the technology they will use than ever before.

Today, a new set of companies are flipping legacy thinking, with Workday, Salesforce, Zendesk, GoodData, Asana, ServiceNow and others delivering simple, open, and platform-agnostic solutions. Vendors that don’t support the multi-platform world we live in with a user-centric mindset will be locked out. Software that isn’t used gets shut off.

For those leaders and organizations that do make the leap, IT will become more competitive and valued than ever before. Fewer user complaints, server reboots, and compatibility issues. Employees get the tools they need, the enterprise gets massive productivity gains, and the cycle repeats. Ultimately, there may be little choice in the matter. With the technology inflection points we’re facing today, the IT organizations that will thrive going forward will be those that can navigate these shifts by putting the user at the center.

Don’t Start a Company with Your Business School Pals

If you’re thinking about co-founding a company with your B-school buddy, break it off right now.

This is the “Cool Kids Start Companies” syndrome. But for every Warby Parker or Rent the Runway, there are hundreds more that quietly combust in the background without fanfare or notice. And as I’ve argued before, it’s certainly tempting to imagine that your Batman-and-Robin duo might be the team to beat the odds but it’s just not going to happen (at least for 99.998 percent of new entrepreneurs).

The first issue is sharing the same blinders. Business school often attracts people with similar personality types and perspectives. Seeing the world through the same lens means you can’t anticipate critical questions, factors and influences that should be considered as you think about the market, the product or service you’ll offer, and how to pivot intelligently as your company faces new or unexpected pressures.

Sharing the same strengths is just as risky as sharing the same weaknesses. All too often, MBA students’ previous work experiences center on investment banking, private equity, financial services, consulting, etc – in fact, about 56 percent of Wharton’s 2015 incoming MBA program participants fall in these categories. But a successful start-up requires a technologist – someone with the intelligence and technical skill to, you know, actually build a worthwhile, sellable product – and a product person, one with accurate perspective and a solid handle on penetrating the market you’re hoping to capture.

At the same time, your shared experience is no guarantee that you share the same values. When you go to business school with someone, it’s so tempting to think you hold similar values. After all, you get along so well – all those great memories made hanging out in Cambridge or bonding over living at Schwab. But again, unless you’re asking each other very tough, pointed questions, the way you each perceive and live your values is shrouded in mystery. But rest assured: you’ll almost certainly see reality at precisely the worst possible moment for you and the company. Maybe it’s learning that your co-founder is prepared to work with the wrong venture fund or that they’re actively willing to hide bad results from your board. Whatever the case may be, there is no more fertile ground for conflict than a fundamental mismatch of the values that make you who you are.

Finances make people twitchy – and are another source of conflict. It’s easy – too easy! – to assume that your business school colleague mirrors your perspective on financial issues. False. Each of us comes from different financial backgrounds; just because someone carries a Fendi doesn’t mean she shouldn’t really be driving a Ford. We can have stratospherically different levels of tolerance for risk. Your co-founder may go home, look at her bank account or see his kids’ faces, and succumb to perceived financial pressure to look for a so-called “real job.” We may intellectually understand what’s required of us as co-founders but it may feel very different when we’re in the blood-and-guts of daily decision-making. That especially is true in times of business uncertainty, which is omnipresent in start-ups.

Finally, you just don’t know this person as well as you think you do. Business school relationships are forged in a highly artificial environment – where socialization with others is notoriously cocktail party superficial. You can’t be confident that these people are capable of stepping up to the plate outside the carefully constructed constraints of a hyper-achieving educational environment. It’s like marrying the person you met on vacation under the stars and palm trees. The harsh light of everyday life often reveals a completely different person. Someone who copes just fine with a professor’s deadline or creating a mock business plan could crumble under the pressure of your first pitch to a VC.

Can B-school partnerships ever work? I’m sure there are some exception cases to the rule. But by and large, it’s not a sustainable strategy for long-term success.

The Five Traps of High-Stakes Decision Making

At some point most executive teams will make a bet-the-company decision. Sometimes they’ll make the right one and will be handsomely rewarded. Southwest’s decision in 2007 to hedge against increases in the price of jet fuel proved remarkably prescient. But sometimes the big decision will go horribly wrong. In 2007 AOL and Time Warner finally pulled the plug on the $350 billion 2001 merger that Time Warner chiefs Jeff Bewkes and Gerald Levin later called “the biggest mistake in corporate history.”

In the popular mind, there’s a lot of luck and inspired leadership behind successful choices like Southwest’s. But if you look closely, that really isn’t true. The leadership teams at AOL and Time Warner were hardly boneheaded. To be sure, luck does play a role, but then many companies have enjoyed a quite remarkable run of it, far longer than you might expect if success really is all about luck.

I’ve been studying decision-making at the top for many years and what I’ve found is that the truth is far more prosaic. Good decisions, like Southwest’s, nearly always result from robust decision processes. Similarly, decisions that go wrong, like Time Warner’s, nearly always stem from procedural or organizational failures. In fact, when I and my colleagues at Bain & Company conduct post-mortems into decisions, we find that just five mistakes account for the vast majority of poor decisions:

An unrealistic search for silver-bullet solutions. Most business problems are complex. But many executives badly want a silver bullet — a simple action that will leapfrog the competition or supercharge an organization’s performance in one fell swoop. One example is the corporate reorganization. Nearly half of CEOs reorganize their company in the first two years of their tenure. Many preside over multiple restructurings. Yet fewer than one-third of these moves produce any meaningful improvement in performance. Chrysler reorganized three times in the 36 months prior to its sale to Fiat. Each time, management claimed the reorganization would turn around the ailing automaker. Each time, no turnaround materialized.

So the next time someone asks, “Is there a simple solution to this problem?” be prepared to answer, “Probably not.”

Failure to consider alternatives explicitly. Business is a game of choices, and you can’t make good choices without good alternatives. But most organizations do not explicitly formulate and evaluate alternatives in making big decisions. Imagine what might have happened if the team at Time Warner had considered other alternatives for expanding into the online world: strategic partnerships, joint venture arrangements, even accelerated development of the company’s own capabilities. The act of formulating and evaluating explicit alternatives invariably improves the quality of decision making.

The next time someone recommends a course of action, ask two simple questions: “What alternatives did you consider and reject?” and “Why?”

Too many people involved. Important decisions are hard to make in large groups. Sensitive issues don’t get thoroughly discussed. Personalities interfere with reasoned argument. In fact, our research highlights the “Rule of 7”: for every individual you add to a group beyond seven, decision effectiveness declines by 10%. The success of Apple Computer and Facebook stems in part from their highly streamlined decision-making models. At Ford Motor Company, the senior leadership team addresses the company’s most important decisions in “special attention” meetings limited to a small group of executives.

The next time you receive a meeting request with more than 15 invitees, ask yourself: “Are we really going to be able to make significant decisions in this forum?”

Failure to consider opportunity cost. The decision to start doing something new is only one form of high-stakes decision. Another—often with equally big consequences—is to keep doing something you’re already doing. The decision not to shut down an uncompetitive product line or exit an unprofitable market can consume as much scarce management time and other resources as any merger. Yet few executives appreciate the opportunity cost associated with continuing with a losing venture. Blockbuster’s failure to shut down its legacy bricks-and-mortar operations and shift attention to home delivery and digital downloading doomed the once-powerful retailer.

The next time you are contemplating maintaining a troubled operation, ask yourself: “Where else could we invest the resources that this business is consuming?”

Underestimating the challenges involved in execution and change management. The complexities associated with a big-stakes decision rarely end with the decision itself. Indeed, recent Bain research indicates that only 12% of large-scale changes are executed as intended. That’s because change is hard — and the bigger the change, the bigger the risks. The recent launch of Healthcare.gov may be an example of underestimating implementation difficulties. While the risks associated with the website were predictable, they appear never to have been elevated to the level that demanded action. As a result, responsible officials didn’t take the necessary precautions, and the website all but collapsed during the weeks following its launch.

The next time you are thinking through a big-stakes decision ask yourself: “What happens first thing Monday morning? What behaviors will have to change?”

Big-stakes decisions are just that — big. When they go awry, it is typically because the organization has fallen victim to one or more of these failures. Avoiding them won’t guarantee you success — but it will greatly increase the chance of a better decision.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Making Decisions Together (When You Don’t Agree on What’s Important)

Stop Worrying About Making the Right Decision

Managing “Atmospherics” in Decision Making

The Six-Minute Guide to Making Better High Stakes Decisions

Dave Eggers Wrote the Best Business Book of the Year

Though it’s a work of fiction and not a guidebook full of practical checklists, Dave Eggers’ The Circle may be the most provocative business book you’ll read this year. It challenged me deeply, especially in the areas I’ve focused on for HBR—auto-analytics, wearable computing, and social technology. All feature prominently in The Circle, and not necessarily in the positive way that I view those technologies. But that’s what a good business book should do: challenge your assumptions, and make you think in new ways.

The book surfaced several themes for me that I think are relevant to most managers. Here are a few of them.

The new workplace is abstract (and a bit lonely). The foundation of personal and business relationships has always been face-to-face interaction. The main character, Mae, begins her journey this way, through her personal connection with her former roommate Annie. Annie is an executive at the Circle, a giant company that’s something like a mashup of Google and Facebook. Annie gets Mae a job there.

Mae quickly finds out what many of us in the real world have discovered—that work is focused on digital interactions rather than physical ones. The Circle’s workplace practices are harbingers of this new reality. Facial recognition becomes an act best performed by software, smiles and frowns are done by emoticons, and candid conversations only occur in adjacent bathroom stalls, where faces are walled off. Mae’s old boyfriend Mercer complains: “Every time I see or hear from you, it’s through a filter. You send me links, you quote someone talking to me, you say you saw a picture of me on someone’s wall…It’s always a third-party assault.”

Putting into words what many of us intuitively sense, Eggers demands us to confront the now well-researched idea that increasing digital connectedness is actually making us more isolated.

But maybe this loneliness implies new possibilities too. Maybe, in the real world, a new source of competitive differentiation might come from the oldest one: reestablishing physical contact between people.

Your digital brand isn’t you. My research has looked primarily into the performance benefits of using personal data as a source of private reflection and decision making. By comparison, Eggers’ novel sketches the potential risks of unguardedly making personal information fodder for public consumption.

In an effort to become “transparent,” Mae wears a “life-logging camera,” and turns her job into an Internet reality show. With this she feels increasingly compelled to curate her online presence, to entertain, to engage, and to manage her brand. As Mae’s transparency increases, she quits being herself. Her passion for kayaking withers. Her family identity decays. Even brushing teeth becomes a histrionic act.

Here The Circle poses the question to all those prolific Tweeters and LinkedIn profile micromanagers out there: Do you perhaps see a bit of yourself in Mae?

Measuring knowledge work isn’t easy, and isn’t always equally applied. The story deals extensively with the ambivalence knowledge workers often harbor toward both technology and management-led productivity measures.

Like all members of the Customer Experience (CE) group, Mae’s career develops in step with the number of open windows on her computer she can attend to: “Before the third screen, there had always been a lull, maybe 10 or 12 seconds, between when she’d answer a query and when she knew whether or not the answer had been satisfying…But now that had become more challenging,” as new screens featuring ever more data and customer performance scores .

Toward the end of the story, Mae’s managing nine screens simultaneously.

Yet, even as every aspect of a Circle workers’ lives become ranked and gamified, the work of the Circle’s top executives—“the Three Wise Men”— often remains cloaked in mystery. This inconsistency gives pause to any employee pondering the benefits of having her cognitive contributions quantified on a curve relative to colleagues. Why is it that those that really have a choice decide against transparency for themselves?

What, exactly, is free time? Except for Mae’s Luddite ex-boyfriend Mercer, The Circle’s characters excel at using new technology, not at reflecting on its ensnaring paradoxes. As suggested above, technological self-fashioning is a mode of self-concealment, and multiple open screens designed to create wellsprings of productivity disperse thinking into a bunch of shallow puddles.

The take-away: Big Data won’t necessarily result in deep thinking, at least for most workers.

In particular, Eggers draws attention to how participating in corporate social networks during free time transforms leisure into unpaid labor. Early in her tenure at the Circle, Mae is told by HR that she’s “such an enigma” because she wasn’t posting data and details of her weekend kayaking excursions or trips to visit her struggling parents. That’s a wake-up call for Mae, who resolves to turn every free moment into an opportunity to comment on walls, post updates, engage followers and “watchers,” and improve her “PartiRank”, the Circle’s social media participation ranking system.

This turnaround leads to a rather insidious “profound sense of accomplishment.” Mae gains rank, but she now lacks the leisure time to reflect on how the cost of outstanding social media metrics is leisure itself. (Here I encourage anyone inclined to post this article to their company’s Facebook page as they sit in a restaurant or a movie to reread the previous sentence.)

Management thinking’s long-held assumptions should be revisited. Literary theorists are familiar with the concept of “the hermeneutic circle,” which describes how any single part (a word, a line, a data point) of a book is best interpreted after completing the whole work. The whole explains the deeper meaning of the parts, though individual parts constitute the whole.

This conceptual conceit is in play throughout the novel. Executives seek “to complete the circle,” which means that by accessing the totality of the world’s data, the tech company can then offer a more profound interpretation of human meaning.

By comparison, it’s worth noting that management theory generally assumes that there is no whole—that no organization will have complete knowledge of its customers, employees, markets, and so forth.

However, with so much data flowing through just a few mega-tech companies, maybe it’s time to challenge this assumption a bit.

This is the biggest provocation of all in The Circle. It asks us to imagine an enterprise with the aspiration to know it all, but also forces us to ask whether we should want to play a role in making that happen.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers