Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1517

November 12, 2013

Yes, It’s Worth It to Work Those Long Hours

For young, highly educated workers who usually put in long hours, working 5 extra hours per week is linked to a 1% increase in annual wage growth, according to a study of thousands of U.S. workers by Dora Gicheva of the University of North Carolina. The finding holds only for those who work at least 48 hours per week; when hours are lower than that, there’s no correlation between additional work and wage growth. Males’ willingness or ability to work long hours accounts for some, but not all, of the gender difference in wage growth, Gicheva says.

November 11, 2013

When a Company Is No Longer That into You

Companies are often better at romancing than they are at long-term commitment.

I entered a relationship with Lowe’s almost four years ago. Sure, we’d been acquaintances. I’d seen it when I went to the store next door. I even visited once to buy a hard-to-find light bulb.

But then I bought a house.

Suddenly, Lowe’s was there for me. Before long, I found myself there every weekend — buying everything from plumbing supplies to paint to appliances. When I had an issue, Lowe’s had the answer in stock. And, after a year, I was ready to take our relationship to the next level: a backyard fence.

Lowe’s listened to my needs. They understood what I wanted and offered to help. And, when I decided to buy, the salesman even came to my house on a Sunday afternoon to seal the deal. Soon, they were in my backyard, installing the fence. And Lowe’s offered to answer any questions I had. “Be sure to give us a call if anything ever goes wrong,” they cheerfully told me as they drove away.

It was around a year later that I had to make that call, when my gate opener quit working. Lowe’s didn’t come running immediately like before, but I understood. They had other customers, too. A few days later, someone was out on my property to check things out.

I was in luck. I was in the grace period of my warranty, so Lowe’s would cover the repair completely. I was grateful.

First, we resolved a paperwork issue. Then some weeks passed by.

Every time I looked outside, I thought about Lowe’s, but I knew they’d call soon. Finally, after the weeks had turned into multiple months, I called them. The company that made the gate opener was no longer one of Lowe’s suppliers, but they were figuring out how to get in touch. More months pass. I called again. They had sent an order out to the company, but it was rejected. They were going to resubmit, since it was a warranty replacement. They’d call when they had news.

More months. More calls. The part was in, and a repairman was scheduled to come over. When he did, though, they noticed that the gate’s hinges were breaking and the battery was dead. Not to worry: they’d fix both.

More weeks. Then months. I called. No one answered. I left messages for the department manager. No one called back. Finally, I talked to the store manager. He said he’d get to the bottom of it. No one ever called back.

Just when I’d almost given up, I got through. They’d taken so long, I was told, because the hinges I had were no longer being made. I’d take any hinges they had in stock, I told them, even in a different color. He said they’d replace it in short order.

Days. Weeks. A month. I called. The manager wasn’t in. So I went in person. The team seemed surprised they’d never fixed it. So they walked me over and showed me the hinges they had in stock. They said they’d have a repairperson over later in the week. I called the next day and was again assured it was a priority.

Last month, the one-year anniversary of my broken gate came and went. I didn’t even get a phone call from Lowe’s. Perhaps I could get the store to fix it if I wanted to take some time off work and hang around outside their place until they have time to talk to me. But I don’t want to become “that guy.”

The deterioration of my personal relationship with Lowe’s points toward a larger issue companies face: companies struggle with relationship management. In my situation, the salesperson was great. The install/repairperson seemed helpful and dedicated. The department manager seemed to genuinely want to help. But if this is a hardworking team trying to do a good job, then, how could my experience have gone so wrong?

Communications is not considered an important part of the work flow. For this team, communications is not a primary job function. Even when they were working diligently on my behalf, I wasn’t kept in the loop. From their perspective, they may have been working toward a resolution of my problem at many points along the way. But that was rarely translated to me.

The infrastructure is designed from the company’s perspective rather than the customer’s. The company is most interested in the customer touchpoints at which it derives the most immediate value. The department that sold me the fencing is called “installed sales.” When I encountered a problem, the department I had to take it up with was, again, “installed sales.” I feared I wouldn’t be a priority from the moment I figured that out.

Success is measured primarily by sales. My guess is that this “installed sales” team at Lowe’s is measured–and rewarded–by, well, sales. By that logic, I can’t blame the professionals on that team for putting me at the bottom of their to-do list. From what I could tell, their schedule stays busy, selling and installing.

A sale is the climax for the company but often a milestone in an ongoing relationship for the customer. For most companies, the focus is on driving the customer to the point of purchase. Little emphasis is placed on that customer as a human being with an ongoing relationship beyond those purchases. Yet, the relationship Lowe’s had been building with me would likely have led to loyalty as my go-to resource for home improvement.

Service and communication throughout the customer experience is key to building sustained relationships and driving customer recommendations. Companies often don’t realize the impact their philosophy on relationships has on customers’ lives and the company’s reputation over time. Only when serving the customer who has made a commitment becomes as significant a priority as driving the customer to that choice will a company be able to sustain the sort of customer loyalty it seeks.

7 Policy Changes America Needs So People Can Work and Have Kids

We are in the midst of a revolution in gender roles, both at work and at home. And when it comes to having children, the outlook is very different for those embarking on adulthood’s journey now than it was for the men and women who graduated a generation ago.

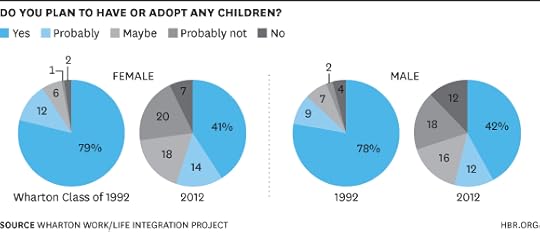

I recently published research from the Wharton Work/Life Integration Project, comparing Wharton’s Classes of 1992 and 2012. One of the more surprising findings is that the rate of Wharton graduates who plan to have children has dropped by about half over the past 20 years.

It’s worth noting that these percentages are essentially the same for both men and women, both in 1992 and in 2012. The reality today is that Millennial men and women are opting out of parenthood in equal proportions.

This change in Wharton students’ plans for parenting is part of a larger trend; a nation-wide baby bust. In 1992, the average U.S. woman gave birth to 2.05 children over the course of her life. By 2007, this number had crept up slightly, to 2.12. But, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the average number of births per woman declined during each of the four years following 2007, dropping to 1.89 (preliminary estimate) — below replacement rate of 2.10 — in 2011. The decline we observed in the Wharton study was more pronounced. While the average 1992 graduate expected to have 2.5 children in his or her lifetime — well above the U.S. mean at the time — the average 2012 graduate planned to have only 1.7.

These numbers are a bit deceiving, however, in one important way: Among those respondents in both 1992 and 2012 who planned to become parents, the number of expected children remained stable at 2.6. What caused the average of the expected number of children to plummet was the sharp decline in the portion of people who planned to have any children, through birth or adoption.

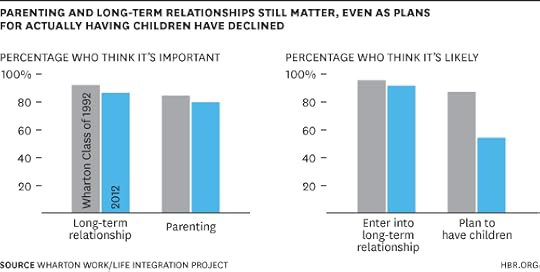

We know, of course, that not everyone wants to be a parent, but the majority still do. The percentage of people who said that being a parent is important in judging the success of one’s life declined only slightly over these two decades, from 84% to 80%.

My research, and that of others, increasingly points to the fact that the thwarting of young people’s aspirations is the result of external pressures that make having both a successful career and a child seem impossible.

Our current capacity to meet this challenge is cause for very serious concern. But there is no one solution; partial answers must come from various quarters. Here are seven ideas for action in social and educational policy, based on my own research — described in Baby Bust: New Choices for Men and Women in Work and Family — and what others have learned:

1. Provide World-Class Child Care. Children require care, yet the U.S. ranks among the lowest in the developed world in the early childhood care we provide. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in a study conducted by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the majority of American day care providers ranked fair or poor and only 10% were deemed of high quality. Yet Americans spend more on child care than other developed countries, and many of those countries are able to provide excellent child care. In addition, the cost of care has doubled since the 1980s, according to the Census Bureau.

Just as bad, if not worse, the K–12 education we offer falls far short of our aspirations and of global norms, and the results are distressing.

A massive overhaul could start with labor market compensation practices. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, child care workers earn even less than home health care workers. A smarter approach would be to treat those who care for children as professionals and to invest in the training and licensing requirements that would be needed to justify much higher rates of pay for those who care for our youngest citizens. High-quality child care not only helps children but enables their parents — mothers and fathers — to engage fully in the workforce without unnecessary distraction and worry.

Our 2012 respondents were attuned to the fact that children require a caring person tending to their developmental needs. This was true the men as well as women. If Millennials want children – and realize wisely that children need to be cared for and that often both parents work outside the home – then we need to step up, as other countries have done, and invest in nurturing our young.

2. Make Family Leave Universally Available. Family leave, including paternity leave, is essential for giving parents the support they need to care for their children. Right now, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics only 11 percent of U.S. employees receive paid family leave from employers. The one public policy that covers time off to care for new children, the Family and Medical Leave Act, laudable though it is, still excludes 40 percent of the workforce. And millions who are eligible and need leave don’t take it, mainly because it’s unpaid, but also because of the stigma and real-world negative consequences.

We need to expand who’s eligible for FMLA and make it affordable; the more people who use it, the less there will be stigma, and a virtuous circle will be created to replace the vicious cycle we have now, wherein parents opt out of work and young workers opt out of parenting. Now, FMLA applies to all public agencies, all public and private elementary and secondary schools, and companies with 50 or more employees. But the rest of American workers are not eligible for the 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave. In other developed countries, family leave is available and it is paid.

The Millennials in our study, including young men, wanted to be engaged, loving, and present parents, but they could not see how they could make this work economically. FMLA is a resource that can provide them with the support they need.

3. Revise the Education Calendar. The standard school day is based on an outdated schedule. Other countries have children in schools for longer days and for a greater part of the calendar year, providing support for working parents and enrichment for children. Friedman’s The Measure of a Nation indicates a correlation of nearly 90% between the number of school days and the results on a world-wide measure of reading, math and science. Revising the school calendar would be a benefit to children, to working parents, and to organizations that would, in the long run, have a better prepared workforce. Having children in school longer hours and for a greater part of the year is yet another way we as a society can help support young dual-career families so that they can envision a way of having their family and work lives in harmony rather than in perpetual discord.

4. Support Portable Health Care. In our study, the anticipated financial costs of childrearing negatively affected Millennials’ plans for becoming parents. Given the rising costs of health care, working parents benefit greatly from health care policies that don’t punish them for taking time off or moving. The Affordable Care Act is a step in this direction. It helps families obtain care while avoiding crippling debt as both parents might now have to navigate careers in which they move from job to job. And preventive care reduces the need for time off due to health problems that afflict workers and their children. This is yet another way that we can ease the burden for those young couples who want to have children and two careers.

5. Relieve Students of Burdensome Debt. Many young people simply can’t envision a future in which they can afford to support children because they are carrying high levels of student debt. Skyrocketing interest rates on student loans and the increasing cost of higher education result in debt burdens are too onerous. Chris Christopher, senior economist at IHS Global Insight, calls student debt “a real monkey wrench in the works of our families and economy,” adding that if college costs and student debt continue to rise, the nation’s low birthrate may become the “new normal.”

Nobel-laureate economist Joseph E. Stiglitz concurs. “Those with huge debts are likely to be cautious before undertaking the additional burdens of a family,” Stiglitz writes. What’s true nationally is also true of the Wharton men we surveyed in 2012. Those men who told us that they had financed their undergraduate educations through employment during school, private loans, government loans, and scholarships and grants were significantly less likely to plan to have children.

6. Display a Variety of Role Models and Career Paths. In our sample, we found that career paths have narrowed because students believe that they must earn money quickly and that only a few options offer this. One man from the Class of 2012 said, “Career paths today seem to be pushed upon students too quickly, or students find themselves in paths they don’t feel are expressing their true selves but are ‘stuck’ due to financial reasons.”

The more that young people hear stories about the wide range of noble, and economically viable, roles they can play in society, the easier it will be for them to choose the roles that match their talents and interests. Young adults would benefit from exploring as wide an array of career alternatives as possible, including and especially those that allow them to have the kind of autonomy and flexibility required to be engaged in both their careers and in their roles as parents.

7. Require Public Service. Our study found that young people today, especially women, want to do work that helps others, despite their expectation that they will not be well compensated for it. And young women who expected their jobs 10 years in the future to provide the chance to serve others were significantly less likely to plan to become mothers.

Young people are yearning to do work that benefits others. Our society could channel that enthusiasm and idealism by requiring a year of public service for postsecondary school youth, which would not only improve our workforce but would help all of us recalibrate what’s really important. And it might help those young women who, as we observed, now foresee a tradeoff between social impact via one’s career and motherhood, to envision instead a life in which they can serve both the family of humanity and a family with children of their own in the scope of their lifetimes.

Of course, there are a lot of unknowns about what our current birthrate means for business. Some argue that in our neo-capitalist society, based as it is on information and finance, there is need for a smaller but more productive labor force. Families no longer need their children for farmhands and so society, and our increasingly automated manufacturing sector, no longer has the same demand for labor. On the other hand, an aging population with fewer workers could mean trouble sustaining social-security programs, projecting military power, and maintaining a high degree of innovation.

But what we do know is that families centered on a single-earner father are no longer the norm. And yet our current institutions are still based on this outdated model. We, as a nation, need to focus on what children in our society require — nurturing. How can they get it if we do not provide the essential social and educational support that working parents need?

Integrating Maintenance of Board Certification and Health Systems’ Quality-Improvement Programs

Health care systems are transforming themselves to deliver the “Triple Aim” of providing better care and a better patient experience, improving the health of populations, and lowering the cost of care. With this in mind, the American Board of Medical Specialties and its 24 member boards in 2006 adopted new standards for physician certification and maintenance of certification (MOC). Meeting MOC requirements is applicable to all board-certified physicians and has four parts that physicians complete every three to 10 years: Part I: Licensure and Professional Standing; Part II: Lifelong Learning and Self-Assessment; Part III: Cognitive Expertise; and Part IV: Practice Performance Assessment.

Part IV of the MOC requirements addresses physician competence in quality improvement. Most physicians complete quality-improvement projects individually by completing modules provided by the specialty certification boards to collect, analyze, and improve quality on subsets of 25 to 50 patients. The boards set the standards and decide whether the physicians have completed this requirement based on the results submitted to them. This approach presents a problem for integrated, multi-specialty systems such as Mayo Clinic and other organizations that are adopting team-based, collaborative models for delivering care: It neither recognizes team-based, multi-specialty projects that physicians are already doing nor promotes organizational effectiveness and efficiency (such as optimizing team-based initiatives instead of having 20 physicians working individually to improve diabetes care).

To address this shortcoming, Mayo Clinic formed a partnership in 2009 with the American Board of Family Medicine, the American Board of Internal Medicine, and the American Board of Pediatrics to create a pilot program: the Multi-Specialty Portfolio Program for Part IV MOC. The pilot has allowed Mayo to oversee and award Part IV MOC to its physicians engaged in frontline as well as institutional efforts to improve patient outcomes, safety, and service.

Mayo was the first care-delivery group to receive this delegated authority. But the program has proven successful and has been expanded to include other specialty certification boards and health care organizations.

Authority and Structure

The ongoing program has allowed Mayo to do the following:

Review and approve (or reject) quality-improvement projects (QIPs)

Develop standards for QIPs

Develop standards for meaningful participation by individual physicians

Distinguish QIPs from clinical research

The initiative consists of three elements:

1. Review and approve QIPs. A quality review board assesses QIPs. It includes five health system engineers, five administrative staff, and 15 physicians representing multiple specialities as well as Mayo Clinic sites in Minnesota, Arizona, Florida, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Georgia. Each QIP is submitted via a web-based portal, evaluated by two members of the quality review board, discussed at biweekly meetings, and assessed for quality-improvement method and meaningful-participation standards. If a QIP is approved, physicians may claim Part IV MOC and continuing medical education (CME) credit; non-physician team members may claim CME credit. Here’s an example of a QIP submission.

2. Quality Improvement Method Standards. Mayo Clinic utilizes the Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control framework as internal standards for quality-improvement methods. Each QIP submitted to the quality review board is required to document the rubric shown in Table 1 and scored accordingly. These standards were developed in partnership with the Mayo Clinic Quality Academy, which oversees teaching, training, coaching, and supporting Mayo’s 60,000 staff to improve patient outcomes, safety, and service. The Mayo Quality Academy offers 30 courses, ranging from Lean and Six-Sigma to Human Factors and Change Management. As of 2012, over 30,000 Mayo staff members had achieved the introductory certification level for competence in knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

3. Meaningful participation standards. In addition to disclosing conflicts of interest, physicians attest to participating in the QIP and report their roles (see Table 2). They also complete a reflection survey: an 18-question instrument to assess critical reflection. As an example, one question asks, “As a result of completing this quality improvement project, I have changed my normal way of thinking about things.” A five-point Likert scale from “definitely agree” to “definitely disagree” is used to record responses from each team member.

Results

From January 2010, when the quality review board became operational, to December 2012, 230 QIPs were reviewed and 168 (73%) of them were approved for Part IV MOC. There were 848 physicians (representing 22% of the 3,800 Mayo physicians) who meaningfully participated and were eligible to claim Part IV MOC and CME. Furthermore, 1,115 allied staff team members participated in these QIPs and were eligible to claim CME credits. During 2011-2012, 14 additional specialty certification boards and 14 health care organizations (including University of Michigan Health System, Partners HealthCare’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, and Kaiser Permanente) have joined this pilot program. (Table 3 lists the certification boards and the health care organizations.)

The types of projects approved by the Mayo quality review board reflect the broad spectrum of quality-improvement activities across Mayo Clinic, ranging from those in small work units to projects sponsored by divisions, departments, and the institution. Teams have included an average of 10 to 15 members (range: 2 to 70) and have been interprofessional (physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, social workers, technicians, managers, and health care engineers). Many projects have been multidisciplinary, involving departments such as Cardiology and Emergency Medicine, Oncology and Radiology, and Surgery and Pathology. Projects have utilized quality-improvement methods, including Lean, Six Sigma, Failure-Modes-and-Effects Analysis, Plan-Do-Study-Act, Run Charts, pre- and post-comparison of bundled interventions, simulation, human factors, and change management.

Assessment of meaningful participation has revealed important insights about teamwork and organizational culture. Here are some comments that people have made:

“As a clinical assistant, I have never presented in front of a group physicians before and this project allowed me to share my ideas and thoughts with them.”

“I understand the bigger picture and see how important standardization and process are to improving patient care.”

“I developed a stronger understanding of the work completed by other disciplines and how to pull everyone together for the best needs of our patients.”

This figure near the bottom of this document shows a “Wordle” of the reflection surveys and sample comments from team members.

Moving Ahead

This pilot program has successfully integrated Mayo Clinic’s ongoing initiatives in quality, safety, and service with the MOC requirements of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Consequently, Mayo Clinic physicians who are actively engaged in QIPs can submit these projects to the Mayo quality review board to be considered for MOC credit. This has transformed MOC into a lifelong learning activity.

The following steps would help accelerate the optimal implementation of this pilot program and expansion to other health care systems:

Get all 24 certification boards to adopt uniform standards for MOC (such as number of points needed each cycle as well as the cycle time to complete those points)

Develop and support learning networks that allow health care systems to share the lessons they have learned and mentor each other in order to elevate the relevance of MOC and overcome common barriers to adoption

Undertake scholarly research on the impact of participating in MOC for physician competence and patient outcomes in order to provide assurances that MOC is meeting the certification boards’ stated mission to serve the profession and the public.

The future model for MOC must strive to achieve the aims of better physician competence, better system competence, and lower cost over time. Mayo Clinic’s partnership with American Board of Medical Specialties and the specialty certification boards is an important step in that journey.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

Liberating Patients from Mechanical Ventilation Sooner

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

Sustainable Business Initiatives Will Fail Unless Leaders Change Their Mindset

Ten years ago, sustainability issues were not considered business issues. But today, most major corporations have a sustainability function. Increasingly, companies are applying data-driven methodologies such as carbon footprinting, product indexing, lifecycle analysis, and ecosystem services valuation to support smarter decision-making and business innovation.

Yet, if the ultimate goal is to bend the arc of unsustainable business practices enough to make a crucial difference, we still have a long way to go.

The accumulating scientific evidence regarding climate change, ecosystems loss, water shortages, and other changes is disheartening. And business leadership knows it. In a recent survey of 1,000 CEOs of large companies in 27 industries across 103 countries, only 32% believed that the global economy was on track to meet the sustainability needs created by a growing population and rising environmental and resource constraints. Far from scaling back on resource use, we’re consuming more resources than ever – even as sustainability mainstreams.

Why?

Some explanations are simple: Gains in efficiencies are almost always offset by increased consumption. The system changes required to make value chains sustainable require unprecedented levels of trust and cooperation among economic actors. Our current tools, methods, and models for sustainable business are not being adopted at the scale and speed needed to shift the numbers noticeably.

We helped create these tools and we have observed the challenges first hand. We have come to realize that these explanations don’t tell the whole story.

A fundamental and often overlooked cause is a leadership mindset that takes only a partial view of the multifaceted relationship between business and nature. This partial view sees business’s relationship to nature as separate, instrumental, and reducible to market transactions alone. This isolated mindset blinds leadership to the necessary innovations required to profitably address the great systemic challenges before us.

With an isolated mindset, leaders focus mainly on the portion of the business-nature relationship that can be quantitatively analyzed. Less tangible social and ecological factors are considered as context – something that is nice but not essential to the decision-making calculus because it is not measurable.

And yet we know that reasoned analysis alone does not always lead to the right set of actions. This is no less true of sustainable business initiatives, where success depends crucially on how effectively a company engages with stakeholders in two kinds of initiatives: non-corporate stakeholders (such as local communities and NGOs) in sustainable development initiatives, and corporate stakeholders (such as employees or suppliers) in corporate sustainability initiatives. In both cases, the success of sustainable business initiatives is driven not just by the extent to which the company can engage the stakeholders’ reason, but also their emotion and other affective drivers.

To do so effectively, corporate leaders need a different mindset. This new mindset would see business, civil society and nature as deeply and existentially interconnected, acknowledging the limitations of what can be formally analyzed or valued in the marketplace. We call this the integrated mindset because it integrates analytical focus with contextual insights.

First, let’s consider sustainable development. To see why the integrated mindset works better, consider the particular case of a global corporation evaluating the sustainability of major projects in developing countries. Business leaders with an isolated mindset would typically emphasize the economic valuation of natural capital, laws and regulations regarding biodiversity and ecosystems preservation, the availability of economic incentives for sustainable development, return on investment of sustainability efforts, and other factors amenable to quantitative analysis. To such leaders, these are the kinds of factors that will determine the success of their sustainable development efforts.

Leaders with an integrated mindset would consider both the above factors and contextual factors — such as the existential value of nature for many local and indigenous people, the customary rights to ecosystems that are not encoded in the legal systems, the considerable risks related to land tenure and property rights, local perceptions that can damage a corporation’s “social license to operate,” and the impact of poor local and regional governance on sustainable development. While these contextual factors are harder to measure and model, they are nonetheless crucial to engaging effectively with local communities in project design and implementation.

An integrated mindset is especially critical for land-intensive industries like extraction and mining, agriculture, and construction. As the Munden Project reports, the mining giant Vedanta ($12 billion in 2012 revenues) had to abandon bauxite operations in Orissa, India because it did not pay sufficient attention to non-quantifiable contexts. Indigenous groups and other local communities felt shut out of Vedanta’s agreements with the regional government, which agreed to restrict access to land traditionally considered by them to be of cultural and religious importance. The opposition by these local groups led to the abandonment of the project.

And then there is the infamous Madagascar Daewoo project. In late 2008, the South Korean industrial giant Daewoo signed an agreement with the government of Madagascar to eventually lease over 1 million hectares of land to grow food for export. But Daewoo had failed to see the effect it would have on its business context, especially the public perceptions of its project. A new government came to power in early 2009, fuelled by public anger that the agreement would deprive Madagascar of its ability to feed its own people. The incoming president promptly cancelled the agreement by declaring it to be unconstitutional. The largest farmland deal of its kind in the world at that time, it unraveled in just a few months and destroyed Daewoo’s “social license to operate” in Madagascar.

Second, lets consider corporate sustainability efforts, where stakeholders such as employees and suppliers need to be fully engaged. The hard reality is that there are only a few prominent companies that are embracing corporate sustainability practices as a central tenet of their business. This is despite a decade-long effort to demonstrate the business case for sustainable business through the many isolated-mindset-based tools and methods useful for formal analysis. Given this lack of progress, an integrated mindset would go further, and ask the following questions:

What are the insights and practices that will allow us to scale inspiration and commitment to sustainable business inside our company, industry, and value chain?

What are the insights and practices that will encourage a critical mass of corporate coalitions to work together to create a sustainable value chain?

How can we create compelling narratives that combine the head and the heart and inspire employees and business partners to embrace sustainable business practices?

Only by integrating our dominant use of analytical tools, methods, and models with the less measurable, more qualitative insights from contextual understanding can we truly tackle the massive challenge of sustainable business in a profitable way. In the absence of an integrated mindset for sustainable business, we will continue to pursue partial solutions that are bound to fail — and lose a lot of shareholder money along the way.

To create truly sustainable businesses, business leaders must evolve to more effectively integrate focused analysis with contextual understanding. As Proust famously said: “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.”

Managing Complexity Is the Epic Battle Between Emergence and Entropy

The business news continues to be full of stories of large companies getting into trouble in part because of their complexity. JP Morgan has been getting most of the headlines, but other banks are also investigation. And many companies from other sectors, from Siemens to GSK to Sony, are under fire.

It goes without saying that big companies are complex. And it is also pretty obvious that their complexity is a double-edged sword. Companies are complex by design because it allows them to do difficult things. IBM has a multi-dimensional matrix structure so that it can provide coordinated services to its clients. Airbus has a complex process for managing the thousands of suppliers who contribute to the manufacturing of the A380.

But complexity has a dark side as well, and companies like JP Morgan, IBM, and Airbus often find themselves struggling to avoid the negative side-effects of their complex structures. These forms of “unintended” complexity manifest themselves in many ways – from inefficient systems and unclear accountabilities, to alienated and confused employees.

So what is a leader to do when faced with a highly complex organization and a nagging concern that the creeping costs of complexity are starting to outweigh the benefits?

Much of the advice out there is about simplifying things – delayering, decentralizing, streamlining product lines, creating stronger processes for ensuring alignment, and so on. But this advice has a couple of problems. One is that simplification often ends up reducing the costs and benefits of complexity, so it has to be done judiciously. I have written about this elsewhere.

But perhaps the bigger problem is this advice is all offered with the mentality of an architect or engineer. It assumes that Jamie Dimon was the architect of JP Morgan’s complexity, and that he, by the same token, can undo that complexity through some sort of re-engineering process.

Unfortunately, organizational complexity is, in fact, more complex than that. To some extent, organizations are indeed engineered systems – we have boxes and arrows, and accountabilities and KPIs. But organizations are also social systems where people act and interact in somewhat unpredictable ways. If you try to manage complexity with an engineer’s mindset, you aren’t going to get it quite right.

I have been puzzling over complexity in organizations for a while now, and I reckon there are three processes underway in organisations that collectively determine the level of actual complexity as experienced by people in the organization.

1. There is a design process –the allocation of roles and responsibilities through some sort of top-down master plan. We all know how this works.

2. There is an emergent process – a bottom-up form of spontaneous interaction between well-intentioned individuals, also known as self-organzsing. This has become very popular in the field of management, in large part because it draws on insights from the world of nature, such as the seemingly-spontaneous order that is exhibited by migrating geese and ant colonies. Under the right conditions, it seems, individual employees will come together to create effective coordinated action. The role of the leader is therefore to foster “emergent” order among employees without falling into the trap of over-engineering it.

3. Finally, there is an entropic process – the gradual trending of an organizational system towards disorder. This is where it gets a bit tricky. The disciples of self-organizing often note that companies are “open systems” that exchange resources with the outside world, and this external source of energy is what helps to renew and refresh them. But the reality is that most companies are only semi-open. In fact, many large companies I know are actually pretty closed to outside influences. And if this is the case, the second law of thermodynamics comes into effect, namely that a closed system will gradually move towards a state of maximum disorder (i.e. entropy).

This may sound like gobbledegook to some readers, so let me restate the point in simple language: as organizations grow larger, they become insular and complacent. People focus more on avoiding mistakes and securing their own positions than worrying about what customers care about. Inefficiencies and duplications creep in. Employees become detached and disengaged. The organization becomes aimless and inert. This is what I mean by entropy.

The trouble is, all three processes are underway at the same time. While top executives are struggling to impose structure through their top-down designs, and while well-intentioned junior people are trying to create emergent order through their own initiatives, there are also invisible but powerful forces pushing the other way. The result is often that everyone is running very fast just to stand still.

So let’s return to the leader’s challenge. If these three processes are all underway, to varying degrees, in large organizations, what should the leader do? Well, sometimes, a sharply-focused and “designed” change works well, for example, pushing accountability into the hands of certain individuals who are much closer to the customer.

But more and more the leader’s job is to manage the social forces in the organization. And based on the points made above, it should be clear that this effort can take two very different forms:

Keeping entropy at bay. This is the equivalent of tidying your teenager’s room. It involves periodically taking out layers of management, getting rid of old bureaucratic processes that are no longer fit for purpose, or replacing the old IT system. It is thankless work, and doesn’t appear to add any value, but it is necessary.

Inspiring emergent action. This is the equivalent of giving a bunch of bored teenagers a bat and ball to play with. It is about providing employees with a clear and compelling reason to work together to achieve some sort of worthwhile objective. It isn’t easy to do, but when it works out the rewards are enormous.

And here is the underlying conceptual point. The more open the organization is to external sources of energy, the easier it is to harness the forces of emergence rather than entropy. What does this mean in practice? Things like refreshing your management team with outside hires, circulating employees, making people explicitly accountable to external stakeholders, collaborating with suppliers and partners, and conducting experiments in “open innovation”.

A lot of these are initiatives companies are trying to put in place anyway, but hopefully by framing them in terms of the battle between emergence and entropy, their salience becomes even clearer.

The Value of Being the “Weird” Job Candidate

In the 1930s, Hedwig von Restorff, a German psychologist, made an important, though not very counterintuitive, discovery: things that somehow stand out are remembered more easily than typical things. Suppose we read the following list to a group and then asked them to recall it:

apple, truck, necklace, tomato, glass, dog, rock, umbrella, butter, spoon, Lady Gaga, pillow, pencil, chocolate, desk, banana, bug, soup, milk, tie

One doesn’t need to be a German psychologist to see that “Lady Gaga” will be more easily remembered than, say, “butter.” In the context, “Lady Gaga” is atypical, and that’s why she’d be remembered more easily. That’s the von Restorff Effect in action.

Now think about a typical hiring process. A company makes an announcement for a position opening; many people apply; a subset of applicants get interviews; and after the interviews, a group within the company decides whom to hire. Anyone who’s been involved in the hiring process knows that a lot of the discussion around hiring depends on what people “remember” about the interviewees. Of course, there are concrete things to consider (e.g., CVs, psychometric test scores, etc.), but people’s recollections also play a big part:

“I remember that guy was quite arrogant.”

“Actually, I thought he was extremely polite.”

“Didn’t he consistently interrupt you when you were asking him questions?”

“No, he had fantastic manners. He was the last in and last out of the elevator every time — a true gentleman.”

“Okay — maybe it was one of those other guys I had in mind. Did the elevator guy keep making weird jazz references?”

“That’s him.”

“Oh, I liked him. He was cool.”

In a crowded field — and it feels right now that most fields are crowded — the most disadvantaged people to be in this situation are those “other guys,” the ones who cannot be recalled vividly.

After talking with many hundreds of MBA students searching for jobs, I’ve learned many things. One is that people (or at least MBAs) looking for jobs tend to become quite risk averse. When interviewing, they don’t want to do anything “strange.”

But if you take Frau von Restorff’s findings on board I think you’ll agree with me that the conservative folks are making a tactical mistake.

Oscar Wilde, speaking through the character Lord Henry in The Picture of Dorian Gray, understood this: “It is silly of you, for there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

In the pile your file is in, probably most people went to similar schools, have quite similar CVs, and so on. But what will make people remember and talk about you? How are you atypical? It’s not that you have 10 rather than 12 years experience. It’s not that you managed 32 rather than 16 people. How are you really atypical? How will you be remembered in that hiring meeting? Will you be remembered or just be one of those other guys?

Like Oscar, Lady Gaga gets this, and she’s been hugely successful as a consequence. In The Fame she tells us: “I’m obsessively opposed to the typical.” And of course “Lady Gaga” isn’t a typical name. (Does anyone here remember that Stefani Germanotta?)

So when the files are discussed, how will you be separated from the other guys? Maybe it’s because you cited Jay-Z rather than Warren Buffet (Jay’s buddy, actually) as the reason you wanted to go into private equity. Maybe it’s because you had a spider tattoo on your thumb. Maybe it’s because you worked as a bartender in Cambodia for two years after college. Maybe it’s just because you were you and didn’t try to be the McHire-Me you thought they wanted.

Perhaps you can leverage the Lady Gaga Effect: be opposed to the typical. Don’t be afraid to be weird (you probably are) — at least you’ll be remembered. And you know the only thing worse than being remembered…

Jack Ma on Taking Back China’s Blue Skies

Despite the incredible transformation China has gone through over the last several decades, we face tremendous challenges going forward. Issues such as economic reform, social inequality and environmental problems are becoming mind-boggling.

Chinese people used to feel a sense of pride for being the world’s factory. Now, everyone realizes what it costs to be that factory. Our water has become undrinkable, our food inedible, our milk poisonous, and worst of all, the air in our cities is so polluted that we often cannot see the sun. Not long ago, a couple of my friends celebrated a day of blue skies in Beijing on Weibo. It was as if they had just claimed their year-end bonuses. Sadly, something that used to be part of our normal, everyday life has turned into a surprising, all-too-infrequent gift today. Meanwhile, cancer — a rare word in conversation thirty years ago — is now an everyday topic. China must seek to change all of this, but the challenge is huge.

Still, when I think about where we are heading, I am optimistic — because in less than one generation, the Internet has revolutionized how Chinese people live, learn, work and play. We trust each other more. And this is only the beginning.

I feel fortunate to be part of the Internet Age, and to have had the opportunity to build a business along the way. The most enjoyable part of building a business, at least for me, is that it allows us all to contribute to the future. It’s not just about making money. It’s about making “healthy” money — sustainable money that’s not only good for shareholders and employees, but is also good for society, as it enables people to live better lives.

It’s easy to see what I’m talking about by observing changes in Chinese retail, the industry currently most affected by e-commerce. Traditional retailers must guess how much demand the market will create for their goods. Overestimating creates excess stock which must be sold later, while underestimating leaves customers unsatisfied. E-commerce is already allowing Chinese manufacturers to accurately predict demand by improving communication throughout the supply chain, so retailers have less and less inventory sitting idle. Clearly, this helps producers and consumers, but taken as a whole, society is more efficient and everyone is better off. Someday soon, we may even be able to do away with idle stock altogether. This “healthy” business would have been impossible in China before e-commerce.

Just as the Internet is revolutionizing retail, we at Alibaba believe it will eventually do the same to fundamentally information-driven industries such as finance, education, and healthcare. Once this change happens — once we are all connected — I believe the spirit of equality and transparency at the heart of the Internet will make it possible for Chinese society to leap-frog in its development of a stronger institutional and social infrastructure. That’s why we built Alibaba as a “social business” from Day One. Companies in the 21st century need to solve social problems, not just make money — which brings me to my next point: Chinese society needs to rebalance its development priorities to focus more on sustainability. It may take the better part of the next generation, but I believe the Internet has a critical role to play in this discussion by bringing facts to the table and by gathering disparate voices.

We as Chinese citizens must raise awareness as much as possible about our environmental crisis. I am hopeful that the government will become more involved. I actually see the haze in Beijing as a catalyst for change. Before, no matter how hard we appealed to the privileged and the powerful for attention on water, air and food security issues, nobody wanted to listen. The privileged still got their privileged water and privileged food. But everyone breathes the same air. It doesn’t matter how wealthy or powerful you are, if you can’t enjoy the sunshine, you can’t be truly happy.

I believe Chinese society is making progress. Citizens now realize that they can’t wait for the government to take action. Business people are beginning to pay attention to — and take action on — social issues, including the environment. We’re not doing it for PR, but because we know of no alternative. Without progress on the environment, we will find ourselves, our children, and our families hurt even more. Why complain about what government should or should not do while remaining passive? Everybody can make his or her own small contribution. People can look at their own communities, their own neighborhoods, their own nearby lakes and rivers, and try to help.

Small is beautiful. We can do simple and easy things that don’t require money, but will as a whole make a big difference. The more we educate people about the issues, the more progress will be made. I see hope in young people: as more of them become active in our society, in both the public and private sectors, they will bring an understanding of the importance of the problem and force change. It is their job to influence and eventually change the whole system.

Alibaba was founded with a simple mission to help small business owners make money. But our next challenge is to join forces with the people of China and beyond to build an ecosystem that can help even more people make a decent living and push for change that benefits everyone. Twenty years ago, people in China were focusing on economic survival. Now, people have better living conditions and big dreams for the future. But these dreams will be hollow if we cannot see the sun. Therefore, we will continue to build the knowledge and technology to solve our many problems, because the price of failure is simply unbearable.

If we do overcome these problems, the most populous country on earth will make a tremendous contribution to the world. We strive so that when the sun rises tomorrow, we will all be able to enjoy it.

China’s Next Great Transition

An HBR Insight Center

What Business Can Expect from China’s Third Plenum

The Three Reforms China Must Enact: Land, Social Services, and Taxes

Is It Time to Be Skeptical on China?

Do You Really Want to Bet Against China?

Friendly Social Ties Between Merging Companies Can Spell Trouble

Firms are more likely to merge if their directors or senior executives are connected socially, but these friendly ties are associated with lower value creation for shareholders after the merger, according to Joy Ishii of Stanford Graduate School of Business and Yuhai Xuan of Harvard Business School. A 13% increase in the extent of social connections decreases the cumulative abnormal return in the three-day period around the acquisition announcement by about 1 percentage point. Moreover, the presence of social connections between an acquirer and a target makes it more likely that the purchased company will be sold off and that the acquisition will be considered a failure, the researchers say.

Real Men Go to Sleep

The two largest time commitments for most adults on this planet — sleep and work — too often make uneasy bedfellows. The proliferation of nonstandard work schedules and, for many, the outright abandonment of schedules have made traditional daytime-weekday patterns less common. Approximately one in five American workers now functions under some variety of nonstandard schedule. Meanwhile, about half of the nation’s night-shift workers sleep six hours or less per day. The demands of other unconventional arrangements, such as multiple job-holding and independent contracting, have also contributed to the sleep deprivation that plagues much of the workforce.

Add it all up and roughly thirty percent of working Americans survive on less than six hours of unconscious rest a day. They exist on the groggy side of a sleep divide, at an uncomfortable and unhealthful distance from the relatively well-rested majority of employees. Lost sleep impairs decision-making capability, undercuts productivity, and contributes to expensive adverse health effects, including elevated risks of cardiovascular and gastrointestinal conditions.

Unfortunately, a deeply embedded American cultural tradition dismisses sleep as a waste of time. At least since General Electric founder Thomas Edison declared sleep “an absurdity, a bad habit” a century ago, many successful business leaders have promoted a virtual cult of overextended wakefulness, often amplified by considerable media attention to their behavior and commentary. From the Wall Street dynamos monitoring and mastering global financial markets at all hours of the day and night to the NFL coaches living all season in their offices, a sizable contingent of self-disciplined professionals in positions of authority continue to perpetuate unhealthful patterns by pushing themselves and others under their control to turn work into a restless marathon.

The primary message — sometimes implicit, often boastfully announced — is that extended sleeplessness represents a form of masculine strength, leaving those taking a moderate amount of rest as effeminate weaklings destined to lose out in fierce marketplace competition. As one corporate executive put it not long ago, “Sleep is for sissies.” Senior partners in high-powered law firms ask striving young associates preparing for a big case whether they would rather sleep or win.

This dangerous attitude has come under mounting criticism. Journalist Edward Helmore captured the shifting climate of opinion at the dawn of the new millennium, dismissing Donald Trump (perhaps too hastily) as “the last cheerleader of sleeplessness” and presenting as a substitute role model Albert Einstein, who dozed ten hours a day. An abundance of scientific findings, many from research sponsored by the military and NASA, has led many executives to abandon the quest to minimize sleep unreasonably. Some prominent figures, like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, openly embrace and advocate a moderate alternative. Moreover, the growing ranks of proponents of work-life balance have tied male champions of heroic wakefulness to outmoded standards that took little or no account of time-consuming domestic duties.

The heartening result is that there is a growing appreciation of the value of sleep-promoting policies and practices within the business community. Arianna Huffington is a role model in this regard. Beyond raising the visibility of the problems stemming from chronic sleep deprivation and shaping the public conversation about it, she has instituted practical reforms in her own company. The state-of-the-art nap rooms at the New York offices of the Huffington Post allow employees a productivity-enhancing respite. Other major employers permitting and even encouraging napping on their premises include Nike, Google, and Time Warner.

Other commonplace efforts at workplace health promotion promise to pay dividends for sleep health, even as they rein in health benefit expenditures. Obstructive sleep apnea has reached epidemic proportions, sending countless men and women to work in an unrested or underrested state. Obesity sits at the top of the list of risk factors for this sleep-wrecking disorder. Human resource managers and other managerial decision makers have seized on their numerous opportunities to intervene to promote employee weight loss. Provision of either onsite fitness facilities or subsidies for membership in offsite fitness centers is a well-established benefit at many companies. Many worksite vending machines now stock more healthful offerings than the fattening fare that has long predominated. Wider recognition of the link between excess body weight and sleep disruption should help to diffuse further these health-promotion initiatives.

There is another major change, however, that more companies should be making – and that to depends mostly on their resolve. Rearrangement of work schedules virtually always lies within the realm of management prerogative. Some enlightened employers have retreated from use of the most physiologically unnatural schedules, such as rapidly rotating shifts. Some have granted varieties of flexible working time that give the employee considerable discretion in finding sufficient time to sleep. More radical possibilities might extend to reassessing more fully the real costs of graveyard shifts and other nonstandard schedules.

That firms would curtail or eliminate sleep-disrupting work schedules is admittedly an improbable move – it would certainly go against the grain in our nonstop 24/7 world. But such measures would aid significantly in bridging the growing sleep divide in working America.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers