Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1518

November 11, 2013

Indies Need to Push Back More on Amazon

Amazon — the king of e-books and deep discounts — has offered an olive branch of sorts to indie bookstores via its new Source program. It works like this: If stores agree to sell Kindles, Amazon will offer them a 10% commission on every e-book a customer purchases on a device bought at the store for the next two years. It’s a tempting deal for indies, for sure, but it’s far from ideal. The biggest problem is the two-year commission window. That’s too short. It should last as long as the device does.

November 8, 2013

Stop Worrying About Making the Right Decision

Much of my work as a coach involves helping people wrestle with an important decision. Some of these decisions feel particularly big because they involve selecting one option to the exclusion of all others when the cost of being “wrong” can be substantial: If I’m at a crossroads in my career, which path should I follow? If I’m considering job offers, which one should I accept? If I’m being asked to relocate, should I move to a new city or stay put?

Difficult decisions like this remind me of a comment made by Scott McNealy — a co-founder of Sun Microsystems and its CEO for 22 years — during a lecture I attended while I was in business school at Stanford: He was asked how he made decisions and responded by saying, in effect, It’s important to make good decisions. But I spend much less time and energy worrying about “making the right decision” and much more time and energy ensuring that any decision I make turns out right.

I’m paraphrasing, but my memory of this comment is vivid, and his point was crystal clear. Before we make any decision — particularly one that will be difficult to undo — we’re understandably anxious and focused on identifying the “best” option because of the risk of being “wrong.” But a by-product of that mindset is that we overemphasize the moment of choice and lose sight of everything that follows. Merely selecting the “best” option doesn’t guarantee that things will turn out well in the long run, just as making a sub-optimal choice doesn’t doom us to failure or unhappiness. It’s what happens next (and in the days, months, and years that follow) that ultimately determines whether a given decision was “right.”

Another aspect of this dynamic is that our focus on making the “right” decision can easily lead to paralysis, because the options we’re choosing among are so difficult to rank in the first place. How can we definitively determine in advance what career path will be “best,” or what job offer we should accept, or whether we should move across the country or stay put? Obviously, we can’t. There are far too many variables. But the more we yearn for an objective algorithm to rank our options and make the decision for us, the more we distance ourselves from the subjective factors — our intuition, our emotions, our gut — that will ultimately pull us in one direction or another. And so we get stuck, waiting for a sign — something — to point the way.

I believe the path to getting unstuck when faced with a daunting, possibly paralyzing decision is embedded in McNealy’s comment, and it involves a fundamental re-orientation of our mindset: Focusing on the choice minimizes the effort that will inevitably be required to make any option succeed and diminishes our sense of agency and ownership. In contrast, focusing on the effort that will be required after our decision not only helps us see the means by which any choice might succeed, it also restores our sense of agency and reminds us that while randomness plays a role in every outcome, our locus of control resides in our day-to-day activities more than in our one-time decisions.

So while I support using available data to rank our options in some rough sense, ultimately we’re best served by avoiding paralysis-by-analysis and moving foward by:

paying close attention to the feelings and emotions that accompany the decision we’re facing,

assessing how motivated we are to work toward the success of any given option, and

recognizing that no matter what option we choose, our efforts to support its success will be more important than the initial guesswork that led to our choice.

This view is consistent with the work of Stanford professor Baba Shiv, an expert in the neuroscience of decision-making. Shiv notes that in the case of complex decisions, rational analysis will get us closer to a decision but won’t result in a definitive choice because our options involve trading one set of appealing outcomes for another, and the complexity of each scenario makes it impossible to determine in advance which outcome will be optimal.

Two key findings have emerged from Shiv’s research: First, successful decisions are those in which the decision-maker remains committed to their choice. And second, emotions play a critical role in determining a successful outcome to a trade-off decision. As Shiv told Stanford Business magazine, emotions are “mental shortcuts that help us resolve trade-off conflicts and…happily commit to a decision.” Going further, Shiv noted, “When you feel a trade-off conflict, it just behooves you to focus on your gut.”

This isn’t to say that we should simply allow our emotions to choose for us. We’ve all made “emotional” decisions that we later came to regret. But current neuroscience research makes clear that emotions are an important input into decision-making by ruling out the options most likely to lead to a negative outcome and focusing our attention on the options likely to lead to a positive outcome. More specifically, research by Florida State professor Roy Baumeister and others suggests that good decision-making is tied to our ability to anticipate future emotional states: “It is not what a person feels right now, but what he or she anticipates feeling as the result of a particular behavior that can be a powerful and effective guide to choosing well.”

So when we’re stuck or even paralyzed by a decision, we need more than rational analysis. We need to vividly envision ourselves in a future scenario, get in touch with the emotions this generates and assess how those feelings influence our level of commitment to that particular choice. We can’t always make the right decision, but we can make every decision right.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Managing “Atmospherics” in Decision Making

The Six-Minute Guide to Making Better High Stakes Decisions

Learning From Bad Decisions in “Disaster Lit”

That Hit Song You Love Was a Total Fluke

China Can’t Be a Global Innovation Leader Unless It Does These Three Things

When the Chinese Communist Party’s central committee wraps up the Third Plenum on November 12, 2014, a shift from efficiency to innovation will likely be one of the major planks in its vision for China. The government’s imperatives are clear: It wants to double incomes by 2020 in the face of a declining population of working-age; an appreciating currency, and, relative to other emerging economies, high and rising wages. Promoting innovation is also one of the eight key reform priorities in the “383” plan being circulated by the State Council’s Development Research Center.

Trouble is, realizing the objectives around innovation will be not be easy in China, and will require the Chinese government to surmount a number of formidable hurdles.

Some argue that China is already well on its way to becoming a global innovation power that will rival the US and Europe. The “input” indeed appears impressive: China’s R&D expenditure increased to 1.6% of GDP in 2012 from 1.1% in 2002, and should touch 2.0% by 2020, according to the World Bank. China’s share of the world’s total R&D expenditure grew to 13.7% in 2012, and was second only to that of the US, whose share was 29% in 2012.

At first blush, even the output looks impressive. China is well on its way to doubling the number of patent applications filed with the State Intellectual Property Office, from 1 million in 2010 to 2 million by 2015. However, the vast majority of these applications are for utility model patents that undergo a preliminary examination for formalities rather than substance — a concept that does not exist in the US. According to a Shanghai-based patent attorney quoted by the Economist: “Patents are easy to file but gems are hard to find in a mountain of junk.”

Other measures suggest that the productivity of China’s innovation system is low. In 2012, the share of China-based inventors in patents granted by the US Patent and Trademark Office and the European Patent Office was 1.8% and 1.2%, respectively, versus 20.0% and 19.6% in the case of, say, Japan. Thomson Reuters’ 2013 ranking of the world’s top 100 innovators doesn’t include a single company from China. As Lee Kai-Fu, one of China’s best-known venture capitalists and former president of Google China, recently pointed out, what Chinese entrepreneurs do today is iterative innovation; that is, borrowing an existing idea and tweaking it for the Chinese market.

China accounts for 20% of the world’s population, 11% of the world’s GDP, 14% of the world’s R&D expenditure — but less than 2% of the patents granted by any of the leading patent offices outside China. Further, half the patents that originated in China have been granted to subsidiaries of multinationals. Similarly, China awards more doctoral degrees every year than any other country: Over 60,000 in 2012, up from 12,000 in 2000. What isn’t so well known is that in China, the average time required to complete a doctoral degree is just three years, about half that of the US, and most candidates’ dissertations don’t require the approval of a committee of professors.

Why is there such a big gap between China’s standing on the input versus the output side of the R&D equation? With rare exceptions such as Huawei and ZTE, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) rule the corporate landscape in China. Their primary goal is employment and job creation, not disruptive innovation that may be risky but could create shareholder value. They enjoy privileged access to inputs and don’t have to face much competition, so innovation is not a top priority. That’s also why, other than Huawei and ZTE, there is no Chinese equivalent of an IBM, a GE or a Honeywell.

The allocation of the Chinese government’s R&D funds depends far more on whom you know than what you know. As Yigong Shi and Yi Rao, deans of life sciences at Tsinghua and Peking Universities, respectively, observed in an editorial in Science magazine, when it comes to government grants, “it is an open secret that doing good research is not as important as schmoozing with powerful bureaucrats and their favorite experts… China’s current research culture… wastes resources, corrupts the spirit, and stymies innovation.”

China’s R&D culture suffers from a focus on quantity over quality, the use of local rather than international standards to reward research productivity and grant patents, and a continuing weakness in the enforcement of laws to protect intellectual property. The result is not just a focus on incremental advances, but also the duplication of proven knowledge.

China’s educational system emphasizes rote learning rather than creative problem solving. As Lee Kai-Fu noted: “The Chinese education system makes people hardworking, teaches people strong fundamentals, and makes them very good at rote learning. It doesn’t make them creative, original thinkers.” Iconoclastic minds either are channeled into conventional thinking or “become outcasts and their parents would think they’d gone crazy.”

Innovation thrives in a culture of diversity where people don’t feel the compulsion to fit in and where those with strong backbones are likely to be viewed as heroes. Unlike the US, especially Silicon Valley, which thrives on a diversity of ethnicity, national backgrounds, cultures, and languages, China is largely a sea of homogeneity.

Many Chinese executives seem to recognize the challenges. Over the last two months, we conducted workshops for three groups of senior executives from some of China’s largest state-owned enterprises. An anonymous survey shows that over half the executives believed that China would have a bigger economic power than the U.S. in 2025. However, only 13% believed that China would have overtaken the US on the technology frontier by then.

The desire of the new Chinese leadership to make the country a global leader in innovation is laudable, but to ensure that happens, they must focus on three areas:

Allow top-tier scientific panels rather than bureaucrats to allocate government funds for R&D.

Force SOEs to face the winds of competition more fiercely than in the past, and

Recognize that while a weak intellectual property regime may provide some help in the transfer of technology from abroad, it creates a serious disincentive to genuine innovation by top Chinese talent.

The issue then is whether the Chinese government will be able to bring about those reforms soon or whether they will have to wait for another generation of leaders.

China’s Next Great Transition

An HBR Insight Center

The Three Reforms China Must Enact: Land, Social Services, and Taxes

Is It Time to Be Skeptical on China?

Do You Really Want to Bet Against China?

China’s Impending Slowdown Just Means It’s Joining the Big Leagues

What Really Led to Last Summer’s Most Notorious Firing

For a few days last August, it was one of the most talked-about business stories in America: Tim Armstrong, the CEO of AOL, fired someone abruptly during a meeting. A recording of the incident went viral. What made the typically affable Armstrong snap? In this massive piece, Nicholas Carlson analyzes Armstrong's rise from his days as the owner of a strawberry business, uncovering a leadership trajectory that culminated in a proxy war with an activist investor and a final realization that his baby — local-news and listings provider Patch — needed to be trimmed, or else.

A thread running through the story is Armstrong's likability and loyalty. He was the "golden boy," so well-liked that he was able to overstep boundaries. At Google, he knew he needed to simplify his huge sales staff, but instead of making hard choices that could damage friendships, he put off any decisions and later left for AOL.

There's so much more in the full article, particularly about Patch, which was supposed to be AOL's savior and instead became an even bigger elephant in the room than Google's complex sales arm. Armstrong told his board he could make Patch profitable within a year, but it didn’t happen. Last August, feeling awful, he knew he had to face the consequences and make unpopular choices. "For so long, it was a price he had never had to pay," writes Carlson. Armstrong was so emotional that it didn’t take much to provoke him. And we all know what happened next.

Networking with NobodiesStroke of Luck: How Entrepreneurs Can Increase Their Chances Australian School of Business

Hoping for a little luck in your efforts to become an entrepreneur? There are things you can do to put yourself in luck's way, says Martin Bliemel of the Australian School of Business. Such as search harder for sources of inspiration. Instead of monitoring the media for new ideas, attend trade shows and conferences and go to talks in areas that are out of your area of knowledge. Also, ask for more than you can reasonably expect. “Don’t be afraid to tell others what you are looking for, even if you think it would be foolish for them to help you,” he says. And network with people – even those who don’t seem to matter. Many entrepreneurs have found opportunities through serendipitous connections. Entrepreneurs have to hone their ability to extract good ideas from surprising sources and turn them into something no one else has thought of. —Andy O'Connell

The Highest StakesLead or DieFast Company

Lt. Col. Phil Treglia wasn't your typical management adviser. A Marine with years of combat experience, he'd never actually advised anyone before. But he volunteered to lead a team to help the Afghan Army transition to self-reliance in advance of the U.S. military withdrawal. Treglia's mission, as handed down from the higher-ups, was to use his large team to work side-by-side with the Afghan Army — military helicopter parenting, so to speak. The team was given no deliverables; the only end-game message was vague: Give Afghans the ability to be independent after the U.S. leaves.

Treglia decided that, due to this open-ended goal and the difficulty of getting the Afghan Army to learn to do things on their own amid a swarm of advisers, he would go over the heads of his superiors and craft a strategy that relied on a few key takeaways. One: In the long term, soft skills such as mentoring, inspiring, and “selling” (of concepts and goals) would be much more effective than combat drills. Another: Afghan soldiers needed to learn how to be confident in their skills — and that couldn't happen with tons of advisers looking over their shoulders. So he drastically reduced the numbers on site. Lastly: If you're in a big bureaucracy and you're making changes to what's happening on the ground, pretend everything's normal and no one will notice until your plans succeed. "By the time staffers at the regional command fully grasped the change, the program had been humming along for two months and showing good results." And it still is: the British have taken notice of Treglia's methods, and the team he advised is now a model case.

The Most Boring Plotlines Are Our LivesYour Phone Is Ruining You For UsThe Awl

Robert Lanham, a fiction writer and satirist, refuses to set his stories after 2002, roughly the time when our daily activities and emotions started revolving around our smart phones. If he were to write about the present, he’d have to show how boring and uninspired we’ve become, staring minute after minute at those shiny devices. That would make for mind-numbingly dull reading. Even the concept of "unplugging" for a night or a weekend is boring. "Digital detoxes lack passion," he writes. "They're pretentious. They're the commitment equivalent of the hedge funder who uses LED light bulbs on his private jet to be 'environmental.'" Even our outrage is boring — we become insipidly incensed about "some guy who had his phone up in the air for, like, 20 seconds during the glockenspiel solo" of an Arcade Fire concert.

"We need to be embarrassed,” he says. “We need to be mortified by how monotonous we've become." So maybe we should turn our phones off until we actually need them: "Who knows who you've actually become while you were desperately not paying attention?"

GiddyupToyota Made a 4-Wheeled Segway That You Bond With Like a Horse Wired

It has always seemed sad to me that after thousands of years of being bonded with horses, humans have largely lost that relationship. But now there's Toyota’s FV2, a hybrid vehicle that you drive standing up. In that sense, it’s like a chariot, but you're supposed to bond with it, just as you would with a horse. It's controlled like a Segway — there's no steering wheel. To make it move, you shift your body forward, back, left, or right. Funnest of all, the machine uses facial-expression recognition to determine your mood, and the exterior changes color accordingly, says Wired. —Andy O'Connell

BONUS BITSSome Companies You May Have Heard Of

Dell Officially Goes Private: Inside the Nastiest Tech Buyout Ever (Forbes)

The Hidden Technology That Makes Twitter Huge (Businessweek)

Blockbuster Video: 1985-2013 (Grantland)

Is It OK to Yell at Your Employees?

Steve Jobs. Jeff Bezos. Martha Stewart. Bill Gates. Larry Ellison. Jack Welch. Successful. Visionary. Competitive. Demanding. And each with a well-deserved reputation for raising their voices. They yelled. Yelling was an integral part of their leadership and management styles.

Is that bad? Is that a flaw?

Harvard Business School recently published and popularized a case study of Sir Alex Ferguson, Manchester United’s recently retired manager and the most successful coach in English Premier League history. Ferguson was a fantastic leader and motivator. But Sir Alex was particularly famous for his “hair dryer treatment”: When he was angry with his players, he shouted at them with such force and intensity it was like having a hair dryer switched on in their faces.

Does that make Sir Alex’s leadership less worthy of study and emulation?

Of course, that’s sports. Elite coaches worldwide are notorious for yelling at their talented athletes. Vince Lombardi, Mike Ditka, Bela Karolyi, Pat Summitt, and Jose Mourinho were comparably effective at raising their voices to command attention and results. They inspired great performances and even greater loyalty.

High-decibel intensity is similarly found in special forces training and commands in the military. Yelling is intrinsic to elite military unit culture. It’s expected, not rejected. But perhaps the inherent physicality and emotional stresses of those fields make yelling more acceptable than in more creative and aesthetic endeavors.

But wait: Even the seemingly genteel world of classical music evokes clashes other than cymbals. The world’s best and most highly regarded conductors are frequently famous for raising their voices even higher than their batons. Arturo Toscanini, Herbert von Karajan, and even Daniel Barenboim had reputations for making sure their sharper words were heard above the flatter music. For world-class symphony orchestras, world-class conductors’ critiques are seldom sotto voce.

There’s surely never been a shortage of movie and theater directors who emphatically raise their voices to raise the level of performance of their actors and crew. Neither Stanley Kubrick nor Howard Hawks, for example, were mutes.

What’s true for the collaborative arts holds true for the collaborative sciences, as well. Nobelist Ernest Rutherford was a force of nature who rarely hesitated to firmly and loudly make his questions and concerns known during his astonishingly successful tenure running Cambridge’s Cavendish Lab. His Cavendish was arguably the most important experimental physics lab in the world.

To be sure, yelling doesn’t make someone a better leader or manager. But the notion that raising one’s voice represents managerial weakness or a failure of leadership seems to be prima facie nonsense. The empirical fact pattern suggests that in a variety of creative and intensely competitive talent-rich disciplines around the world, the most successful leaders actually have yelling as both a core competence and brand attribute. These leaders apparently benefit from the acoustic intensity of their authenticity and the authenticity of their intensity.

But is that a good thing? Or a necessary evil?

Stanford Professor Bob Sutton, who authored the managerial cult classic The No Asshole Rule is not quick to condemn leaders and managers who raise their voices with intent.

“To me it is all about context and culture,” he told me via email, “and the history of the relationship. So in some settings, yelling is accepted and is not viewed as a personal insult, but an expected part of leadership. The National Football League is an example… I once tried to teach the ‘no asshole rule’ to a group of folks from NFL teams, and in that context, many of the behaviors that might be shocking in a school, company, or hospital were normal. Much of it comes down to intent and impact, so does it leave the person feeling demeaned and de-energized? Or is it taken as acceptable and expected, and even as a sign of caring?”

Exactly. Would you pay more — and better — attention if you were being yelled at by someone who cares as much about the quality of your work as you do? Or would you find it demotivating? Conversely, if — or when — you raise your voice to a colleague, a boss, or a subordinate, do they hear someone whose passion matters more than their volume?

When I look at the organizations that seem to have the greatest energy and drive, the conversations aren’t whispered and the disagreements aren’t polite. Raised voices mean raised expectations. The volumes reflect intensity, not intimidation.

In other words, yelling isn’t necessarily a bug; it can be a feature — a poignant one.

Sutton concluded his email as follows: “Remember the late and great J. Richard Hackman from Harvard? He yelled at me now and then — I mean yelled, swearing, calling me an idiot — when I was about to make some bad career choices. I appreciated it at the time and have loved him more for it over the years. I knew he was doing because he cared and wanted to make sure I got the message. I wish he were here to yell at me right now.”

If you’re yelling because humiliating and demeaning people is part of who you are, you’ve got bigger professional issues than your decibel level. Your organization needs a quiet conversation about whether your people should work a little louder. But if raising your voice because you care is part of who you are as a person and communicator, your employees should have the courtesy and professionalism to respect that.

What Men Can Do to Help Women Advance Their Careers

Over the past few weeks, I have been talking — a lot — about the themes of women and work. About how women haven’t even come close to reaching the heights of professional power that many of us once predicted would shortly come to pass; about how women today remain oddly chained to an expanded and wholly unrealistic set of expectations. And I have also been talking, more than I had imagined I might, about what men can do to address this set of issues.

The good news here, I think, is that there is a lot of good news. Once upon a time — say, maybe 50 years ago — there was undeniably a mindset among many men who, for a variety of reasons, firmly believed that women could never make it in their world. They were men (joined usually by a supportive chorus of women) who thought that women were not competitive or strong enough for the world of work. They claimed women didn’t have the inner fiber and inherent smarts; that a woman’s job was to be home taking care of the children.

These days are now long past. Most men — or at least most of the ones I encounter — are firmly committed to advancing the careers of women around them. They want their wives to succeed; they want their daughters to succeed; they want their female friends to succeed; they want to reap the rewards of investing in the trajectories of female employees and co-workers. The problem is that they just don’t know how. And why should they, given that women themselves are having so much difficulty identifying possible solutions to their plight?

So here, humbly submitted, are five simple things that men can do to help women advance in their careers and their lives.

Do your part on the “second shift.” The home front remains a critical piece of the problem facing working women. So do the laundry. Or the grocery shopping. Or the scheduling of dental appointments. Seriously. Studies (like this one) make clear that while men are doing an increasing amount of work on the home front, they are still leaving the bulk of that work to women, burdening them with the well-known problem of the “second shift.” Men need to increase their share of the daily, mundane, chores. The dishes. The carpools. The packing of lunches and scheduling of play dates. And they need, critically, to take responsibility for whatever tasks fall upon them. Action driven only by nagging isn’t good for anyone.

Take a female colleague to lunch. One of the subtle problems that confront many young female employees is that their male colleagues are scared of them. Scared, that is, that being seen with them will constitute some violation of policy, or at least propriety. The result is that women are often left out of the casual social interaction that provides the bedrock for many professional relationships. Invite women for lunch, or golf, or whatever outings constitute the norm in your organization. And if all your office socializing takes place after-hours, try to come up with activities that fit other schedules, like alternating after-work drinks with before-work breakfasts. Behave appropriately, of course, and make junior women part of a larger group, if possible. But don’t ignore the social side of workplace relationships.

Don’t be afraid to criticize. This, too, is a problem caused by fear. All too often, men in positions of power are afraid to give their younger female colleagues tough feedback. Instead, they waffle and demur, resorting to vague niceties rather than specific criticism. Which means, of course, that the women aren’t getting the advice they need to improve and, eventually, succeed. This doesn’t imply that male bosses should make a habit of yelling at their female subordinates, or that they should rush to give negative feedback. But they should be careful to give young women the same kind of feedback — honest, fair, tough, and specific — that they provide to their male counterparts.

Show up and ask questions. One of the best indicators of an organization’s commitment to diversity is who shows up at diversity-themed events. All too often, only women engage in conversations about balance or family or flexible modes of work. And if the discussions do not extend beyond this population, and outside the realm of women-only functions, then nothing will ever get done. Men who want to help need to be part of the dialogue, and present at those conversations.

Give credit where it’s due – and check if you’re not sure. Every working woman has faced this situation: she offers a point or suggestion in a meeting; watches the conversation move on without notice; and then hears her precise point being echoed five minutes later by a man, whose views are then repeated and praised by the others. So pay particular attention to who is talking during a meeting, and who gets credit for these words. Try to call women participants out by name (“As Sally said just a few moments ago …”) and reference them later in the conversation (“Joe, your idea reminds me of the argument Sally was making earlier…”). Go out of your way to call on quiet people — regardless of their gender — and take the time to learn who really contributed to joint projects or presentations. These practices aren’t just good for women. They are good management, too.

By themselves, of course, these five suggestions will not fix the “women’s problem” that continues to plague our organizations and our society. Bringing men into the conversation, though, and engaging their skills and energies, is an important part of the puzzle.

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

The United States spent 17.9% of the GDP on healthcare in 2012. Academic medicine, which makes up, approximately, 20% of these costs ($540 billion), is under profound threat. Teaching hospitals and medical schools are faced with declining clinical revenue, dwindling research dollars and increasing tuition costs. To meet these challenges, we believe academic medicine must embrace disruptive innovation in its core missions: educating the next generation of health professionals, offering comprehensive cutting-edge patient care, and leading biomedical and clinical research. Medical schools and academic health centers will need to significantly adapt in each of these areas in order to ensure the long-term health of the medical profession. The following are a few examples of disruptive innovations Tulane School of Medicine has embraced.

Medical information doubles roughly every five years, making it impossible for physicians to stay current. Computing power has also increased to the point that machines like IBM’s Watson, first programed to play chess and Jeopardy, are now used to diagnose and recommend treatment for patients. Mary Cummings, one of the first women aviators to land a plane on an aircraft carrier, faced a similar situation when she left the navy; a computer was replacing many of the skills she had acquired in order to fly. Today, as the Director of the Human and Automation Lab at MIT, she poses an important and related question: “Are we in Medicine teaching the next generation of physician’s skills or are we teaching them expertise?” If we are teaching the former, then academic medicine faces obsolescence. However, if we emphasize the latter, our mission is durable. Skills equip people to respond to specific well-understood circumstances; expertise provides the capability to respond to highly complex, dynamic and uncertain environments.

At Tulane University School of Medicine, we believe that the focus of medical education should be on how we teach; because what we teach will be largely out of date by the time students finish their training. The expertise required for the next generation of physicians is to be lifelong learners, team players, educators and problem solvers. We teach expertise through an “inverted” learning model. Students are expected to have reviewed the subject material before class. During class-time the students work in small groups to solve problems and explain to their colleagues issues they did not understand. Master teachers are still needed to facilitate students’ synthesis of material in a collaborative discussion-oriented environment, but this structure has the advantage of allowing investment in the areas where hands-on teaching adds value while providing cost savings in the areas where it does not. The organization that is likely to play a major role in providing on-line medical education is the Kahn Academy under Dr. Rishi Desai. A newly established three and a half year program for medical students with PhDs in the biomedical sciences leverages these adult learning principles. This program shortens the time to get a degree and so reduces the cost of tuition.

Business models for patient care, a key source of revenue for medical schools, are also undergoing enormous change. Driven by the need to lower costs, and aided by new technologies, patient care is moving from the hospital to the outpatient setting and ultimately to wherever the patient happens to be located. For example, when the ACA (Affordable Care Act) is fully implemented in 2014 with a substantial increase in Medicaid recipients, the need for more primary care, as experienced in Massachusetts, will overwhelm the available capacity to provide such care.

One solution to this problem is moving the majority of primary and secondary healthcare delivery into the community. After Hurricane Katrina, Tulane partnered with a network of Federally Qualified Health Centers in order to provide services to low and middle-income patients in community-based clinics designated as medical homes. These not only provide less expensive care, but also provide the kind of experiential learning necessary to teach expertise to trainees. Expansion into telemedicine, which has been shown to reduce the cost of Medicaid in California and has had a dramatic impact in the United Kingdom on patients with diabetes, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, will further reduce costs while improving the quality of care.

Yet another driver of disruption in academic medicine is the changing nature of how research is performed. It has been estimated that for every research grant dollar received by an academic health center, the institution must spend an additional 25 to 40 cents to support that research. Given declining clinical revenues and the relative flattening of the NIH budget, the ability to garner research funding is increasingly competitive and difficult to sustain. For most medical schools, this makes traditional research models inefficient and some institutions that have traditionally been primarily research focused will have to change their emphases.

An additional disruptive technology in research is using “big data,” large data sets that can be analyzed in distributed and cloud computing environments. In 2011, the 3-dimensional structure of a retrovirus protease was finally determined after eluding scientists for over a decade. The configuration was not discovered by a computer, by a single scientist or even by a group of scientists working in a laboratory. Rather, the structure was determined by a group of gamers working in the cloud with a program called Foldit that was developed by computer scientists at the University of Washington in only three weeks. The ability to collaborate without physical interaction using a variety of skill sets challenges the definition and funding models of research (not to mention who gets credit), but has vastly superior economies of scale.

Disruptive technologies threaten every mission of the academic health center. Examples from business have taught us that companies that survive disruption do so by being agile, experimental, problem driven and solution agnostic. Only through embracing coming and inevitable changes head-on rather than remaining entrenched in traditional structures, culture and processes, can academic health centers maintain their pre-eminence and viability. Building on inherent strengths while morphing to embrace change, disruptors can help ensure relevance and maintain competitive advantages.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

Make Physicians Full Partners in Accountable Care Organizations

Employee Engagement Drives Health Care Quality and Financial Returns

The First Step to Being Powerful

“I am such a big failure. I can’t believe that I’ve made this mistake and it’s cost me months and months of time. I might never recover…What an idiot to not see that one coming.” On and on, he went. In distress, my colleague was clearly suffering because of a recent fiasco.

Seeking counsel, he had come to me supposedly to problem solve. But all he could focus on was how this incident made him a failure. I got frustrated listening to him. Not at his words, but at how vicious he was being to himself. In the end, my advice was not as cogent and articulate as I had intended — I used a popular vernacular term for bovine droppings — but I stand by it.

Talking to yourself like you are worthless is not helpful. Yes, mistakes mean you might be in hot water, or that there is a lesson to learn. But there is a huge cost to telling your story in such a limiting way. You give away your power. When you define your “I” as what I call a “weak I” you have lost your ability to effect change.

Sometimes it’s less important to know how to learn specific things, than how growth itself works. You cannot change anything unless first you believe in your ability to drive change. That’s what lets you start to engage ideas, problem solve, enlist others, and focus your energy. In other words, to have an impact, you need to think of yourself with a “strong I”, not a “weak I.”

Most of us talk to ourselves in ways we’d never talk to anyone else. More than likely, you are unkind to yourself when you’ve had a failure. You expect yourself to “get it right” — every single time. More often than not, you hold yourself responsible for the whole of the failure. You believe you should have seen it coming. As if somehow you can actually control everything. But, let me ask you – would you speak to someone else this way? Would you talk to them in an unforgiving, demanding, and invalidating way? Likely not. Were you to say it to someone else, you would almost see him or her shrivel up from the inside. A label given to another person can transform a person’s sense of self and their ability to contribute and create. So can a label you give to yourself.

This is a not about self-help, though it might help you. This is an opportunity to talk about the role of narrative power, through the form of “weak I” and “strong I,” and how it affects our entire economy.

Talent of all sorts is valuable to an organization only when people feel free to bring their differences to work. But all too often, difference is not seen, nor valued. Instead, our difference makes us unseen. I myself fell for this, when someone powerful told me “as a brown woman, the likelihood of you being seen in the world is next to nothing.” I wrote about that experience in a piece on cultural bias. But what I didn’t share then is how much it formed a new weaker narrative in my mind. The “you’ll never been seen” narrative changed my power from a “strong I” to a “weak I” because of the societal group I belonged to. I was a mess for many months. When I didn’t get the role I wanted on a particular board of directors, I thought to myself, “Yes, there! That’s proof that he’s right!” And I started to step back, to stop trying, to deny my own creativity. I had so easily adopted his frame of the world, as my own. It was disempowering, and debilitating.

When I share this personally awkward story in public, I do it to point out a truth about unlocking our economy. New ideas and sources of innovation are abundant. Right, in fact, in front of us — and often hidden in plain sight.

The problem is when those who do not see (the ideas right in front of them, but different than what they expect), believe this means the unseen is not actually there. The argument goes – for example– if there were strong women leaders, OF COURSE we’d see them, maybe even put them on our board. We can’t see them so, of course, they must not exist. (As Claire Cain Miller pointed out of Twitter’s all-male board, this is ridiculous.) Or, when Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos list of favorite books includes only books written by men, some folks online posit that women must not have written important works. To which one might want to look up circular logic.

The debate that often arises when the topic of not-seeing comes up is this: Maybe the people — those not being seen — haven’t not done enough, accomplished enough, or tried hard enough. And unfortunately, this “not enough” narrative plays to some fears on the part of the people not being seen. Me, included. I convince myself that this is something I can control with an action plan. It’s just a matter of jumping a higher hurdle. The thinking goes… once that is done, then I will finally be seen.

But that puts the power of your being seen in someone else’s hands, doesn’t it?

What if the first step in being seen is learning to see ourselves? What if, in our desire to fit in and be seen, we have forgotten how first to belong to ourselves? The more you believe in yourself, the less you need others to do it for you. This doesn’t mean that I deny the role of structural power or cultural power that limit many from being unseen. To make all power about the individual is to privatize power, and to imply that if an entire group of people is unseen, or less seen, that it’s somehow “their fault.” (I’m reminded of the term for bovine droppings, again!)

Yes, it is hard to silence that inner critic — especially if outer critics are also chiming in. If you can’t silence it, make peace with it. I have a standing appointment with fear, where I listen to it and make a plan based on what I learn. In return, fear has learned manners and keeps quiet until our next appointment, thus allowing me to get to work.

You can’t ask other people to make a “weak I” go away. Only you can live your life. And only you have lived the life you’ve lived thus far, only you can have the dreams you choose to have. By asking someone else to validate that, you are not only giving away your power, you asking someone to validate something that they can’t possibly understand. Each of us is standing in a spot only we are standing in; it’s a function of our history and our vision. Until you own this spot – your onlyness — in the world, you will never stand in your power. Without it, you will never fully own your “strong I”. Until you celebrate who you already are, you will always be hustling your way to worthiness, as notable researcher and storyteller Brene Brown would say. She defines hustling as the need to please, perfect, pretend, and to prove your worth. All this is an effort to show the world what you think it wants, not what’s really happening because you don’t believe that your experience, your reality is already good enough.

Professor Amy Cuddy of Harvard knew of research that powerful people have powerful body language—taking up more physical space–and thus appearing more confident to others. She proved that the reverse is also true: just doing powerful poses can actually create the feeling of power. Similarly, I’d argue that by doing the work you’re called to do and by owning your difference, you own your narrative power – and owning it is what lets you create the future.

You do not need to “be seen” before pursuing your ideas. Enjoy yourself. Work. Create. Add value. Do what you can, consider everything an experiment to be held lightly, and then see what it leads to. Trust that in the doing, you are learning and growing, and being powerful. While it is quite possible you will be left “unseen” by some of society, at least you’ll see yourself. In this way, power stretches to become dignity.

Own your story, and you own your life, Justine Musk recently wrote. Talk to yourself as a friend, not an enemy. And remember, you cannot change anything unless you first see your own self as powerful enough to act. The way we talk of ourselves and to ourselves grants power – narrative power — to what happens next.

The Threat of Dismissal Shakes Up Chicago Public Schools

After the Chicago teachers’ union signed a 2004 contract allowing principals to bypass a cumbersome dismissal process and fire recently hired teachers for any reason, faculty absences fell by about 10% and the prevalence of educators with 15 or more annual absences declined by 25%, according to a study by Brian A. Jacob of the University of Michigan. The effect was driven by the voluntary departure of certain teachers after the new policy was announced, he says. Nevertheless, principals were reluctant to enforce the policy: 40% of schools, including many that were low-performing, didn’t dismiss any teachers.

Three Creativity Challenges from IDEO’s Leaders

People often ask us how they can become more creative. Through our work at the global design and innovation firm IDEO and David’s work at Stanford University’s d.school, we’ve helped thousands of executives and students develop breakthrough ideas and products, from Apple’s first computer mouse to next-generation surgical tools for Medtronic to fresh brand strategies for the North Face in China. This 2012 HBR article outlines some of the approaches we use, as does our new book, Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All. One of our top recommendations? Practice being creative. The more you do it, the easier it gets.

Of course, exercising your mind can sometimes feel more daunting than exercising your muscles. So we’ve developed ten creativity challenges to jump-start your practice. Some you can do by yourself; some require a team. Some seem incredibly simple; others you might find more challenging. Three are presented below; we hope you’ll try at least one.

CREATIVITY CHALLENGE #1: PUSH YOURSELF TO THINK DIVERGENTLY

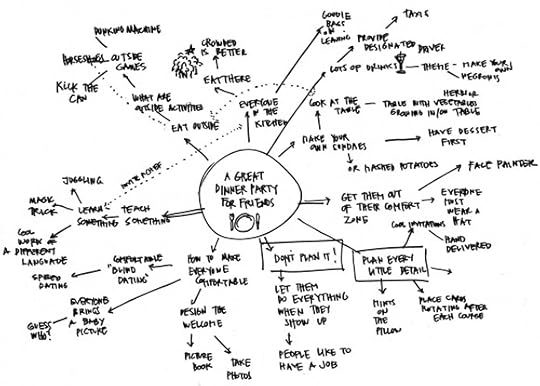

Mindmaps are a powerful way to overcome fear of the blank page, look for patterns, explore a subject, come up with truly innovative ideas, record their evolution so you can trace back in search of new insights, and communicate your thought processes to others. While lists help you capture the thoughts you already have, mindmaps help to generate wildly new ones. They are extremely versatile, and we use them all the time, not only at work but also at home, for example, to come up with dinner party ideas. (See illustration.)

TOOL: Mindmap

PARTICIPANTS: Usually a solo activity

TIME: 15–60 minutes

SUPPLIES: Paper (the bigger the better) and pen

INSTRUCTIONS:

On a large blank piece of paper, write your central topic or challenge in the middle of the paper and circle it.

Ask yourself, “What else can I add to the map that is related to this theme?” Write down ideas, branching out from the center, and don’t worry if they feel clichéd or obvious. That happens to everyone.

Use each connection to spur new ideas. If you think one of your ideas will lead to a whole new cluster, draw a quick rectangle or oval around it to emphasize that it’s a hub.

Keep going. As the map progresses, your mind will open up, and you’ll likely discover some wild, unpredictable, dissociative ideas .

You are done when the page fills or the ideas dwindle. If you’re feeling warmed up but not finished, try to reframe the central topic and do another mindmap to get a fresh perspective. If you feel you’ve done enough, think about which ideas you would like to move forward with.

CREATIVITY CHALLENGE #2: JUMP-START AN IDEATION SESSION

We learned this 30 Circles exercise from David’s mentor, Bob McKim. It’s a great warm-up and also highlights the balance between fluency (the speed and quantity of ideas) and flexibility (how different or divergent they are).

TOOL: 30 Circles

PARTICIPANTS: Solo or groups of any size

TIME: 3 minutes, plus discussion

SUPPLIES: Pen and a piece of paper (per person) with 30 blank circles on it of approximately the same size.

INSTRUCTIONS:

Give each participant one 30 Circles sheet of paper (see example) and something to draw with.

Ask them to turn as many of the blank circles as possible into recognizable objects in three minutes.

Compare results. Look for the quantity or fluency of ideas. Ask how many people filled in ten, 15, 20, or more circles? (Most people don’t finish.) Next, look for diversity or flexibility in ideas. Are the ideas derivative (a basketball, a baseball, a volleyball) or distinct (a planet, a cookie, a happy face)? If people were drawing their own circles, did anyone “break the rules” and combine two or more (a snowman or a traffic light)? Were the rules explicit, or just assumed?

CREATIVITY CHALLENGE #3: LEARN FROM OBSERVING HUMAN BEHAVIOR

You’ve gone into the field in search of knowledge, meeting people on their home turf, watching and listening intently. Now synthesize all that data by creating an “empathy map”.

TOOL: Empathy Map

PARTICIPANTS: Solo or groups of two to eight people

TIME: 30–90 minutes

SUPPLIES: Whiteboard or large flip chart, Post-its, and pens

INSTRUCTIONS:

On a whiteboard or a large flip chart, draw a four-quadrant map. Label the sections with “say,” “do,” “think,” and “feel,” respectively.

Write down each of your key observations from the field on one Post-it note and populate the “say” and “do” quadrants. Try color-coding, for example, using green Post-its for positive statements and actions, yellow for neutral, and pink or red for frustrations, confusion, or pain points.

When you run out of observations (or room) in those quandrants, begin to fill the “think and” and “feel” sections with Post-its, based on the body language, tone, and choice of words you observed. Use the same color coding.

Take a step back and look at the map as a whole. What insights or conclusions can you draw from what you’ve written down. What seems new or surprising? Are there contradictions or disconnects within or between quadrants? What unexpected patterns appear? What, if any, latent human needs emerge?

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers