Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1516

November 13, 2013

You Need More Sleep

Thomas Edison once declared sleep “an absurdity, a bad habit.” It seems that many of us agree: roughly 30% of American workers get by on less than six hours of sleep a day. From Wall Street to NFL offices, from big corporations to small businesses — wherever you work, there’s a good chance that you’re not getting enough sleep, and your work is suffering as a result. Thankfully, a lot of companies are trying to curb the trend with a variety of sleep-promoting policies. But it’s going to take more than naps and fitness plans to get the job done. How about more flexible work schedules?

November 12, 2013

How to Choose the Right Protégé

Ed Gadsden, former chief diversity officer at Pfizer, once asked his sponsor, the legal scholar and federal judge Leon Higginbotham, why he took such an interest in him, aside from the fact they were both African American. “You’re nothing like me, Ed,” Higginbotham told him. “The people you’re around, the things you see, what you’re hearing — you provide a perspective I wouldn’t otherwise have.” Now, as a sponsor himself, Gadsden has come to appreciate the perspective his own protégés provide: “They make sure I’m never blindsided,” he says.

Building a posse of protégés is one of the smartest things a leader can do. Protégés do more than protect you. They extend your capacity and influence. Consider how much more effective — and less overworked — you are as a leader if you have an A-team to turn to whenever a crisis looms, a deadline threatens, or a massive opportunity knocks. A network of protégés makes the impossible possible.

They also add rocket fuel to your career.

In earlier research, the Center for Talent Innovation explored the importance of finding the right sponsor. As I explain in my new book, Forget a Mentor, Find a Sponsor, just as “the sponsor effect” adds a quantifiable boost to a protégé’s pay, promotion, career satisfaction, and retention, “the protégé effect” leverages career traction for leaders. Caucasian leaders with a posse of proactive protégés are 13% more likely to be satisfied with their rate of advancement than leaders who haven’t invested in up-and-comers. Leaders of color who have developed young talent are 30% more satisfied with their career progress than those who haven’t built that base of support.

Consider how organizations assess leadership potential, and it becomes clear why developing a posse of protégés establishes you as “leadership material”: Helping junior people evolve into major producers for the firm is what leaders do. So if you’ve succeeded in grooming a number of people for your position, you’ve made it that much easier for your superiors to promote you, as you will not leave a vacuum they have to fill.

Naturally, good leaders attract a wide field of qualified candidates. How should you decide whom to invest your time in and endow with your knowledge and experience?

Seek loyal, high-potential individuals. Performance is the critical first deliverable. Not surprisingly, what marks an individual as “high potential” is typically his or her ability to deliver superior results consistently, no matter the challenges or circumstances. According to our research, a third of U.S. managers and nearly half of UK managers say they want to sponsor a “producer,” a go-getter who hits deadlines and offers 24/7 support.

Loyalty is even more important, with 37% of male managers and 36% of female managers saying that this is the key attribute in a protégé. A loyal protégé is well-attuned to the buzz and vigilant about keeping her sponsor apprised. As leaders move up the ladder, they’re increasingly removed from the action on the front lines of the organization. They need loyal lieutenants to bridge the distance and deliver a clear, unbiased, and timely report of what’s going on.

Avoid the mini-me syndrome. The reason most multinational leadership is predominantly white and male is that those in power tend to sponsor those who remind them of themselves or those with whom they have much in common. Sponsorship depends on trust, after all, and it is human nature to place our trust in people who share our ethnicity, our religious or cultural background, our educational experience, or our interests. Our research confirms this: When we asked sponsors how they chose their protégés, the majority — 58% of women, 54% of men — owned up to choosing on the basis of comfort.

But if you’re steering a corporation into the churning waters of global competition, you simply cannot afford to pick your first mates strictly on the basis of affinity. Just as companies need a diverse workforce to remain attuned to the needs of new and emerging markets and to develop innovative products that compete in a rapidly evolving marketplace, sponsors need protégés who mirror those markets. The more diverse your team, the more likely you’ll have the toolkits necessary to solve the challenges outside your experience — and the less prone you’ll be to the perils of groupthink.

Fill in your gaps. “The best piece of advice I ever got,” says James Charrington, EMEA chair of BlackRock, “was to have the courage to employ people who are better than me.” He advises in turn, “Recognize your own weaknesses and hire people to complement your strengths by addressing your weaknesses.”

Some protégés bolster your brand through their technical expertise or social media savvy, valuable skills in today’s ever more connected world. Others contribute fluency in another language or culture. Still, others may help you advance the organization’s goals through their ability to build teams from scratch and coach raw talent. The main thing to keep in mind: Shared values more than make up for dissimilar backgrounds.

Limit yourself to a select few. Sponsorship is a high-energy commitment. While it requires less face-to-face time than mentorship, sponsorship requires much more earnest behind-the-scenes work to provide the protégé with concerted advocacy, stretch opportunities, and the air cover necessary to make risk-taking safe. Of course, this investment more than pays for itself in terms of what the protégé returns. But it is an investment. Most senior leaders can effectively sponsor three to four individuals, tops.

Over-sponsoring has its own risks. If you’re hyperextended on behalf of the people who just don’t get the quid pro quo of sponsorship, you impair your ability to be effective. Furthermore, there’s the danger of losing track of your protégé as he gets promoted out of your line of sight.

Choose protégés you can trust. When a sponsor doesn’t really know the person he or she advocates for, his or her credibility in the organization can take a hit. If your protégé isn’t doing a good job, he reflects badly on you. “He’s walking around with your brand on,” said one senior executive. “If you can’t stay involved in his career path — don’t get involved in the first place. Your reputation is at risk.”

And not just your present reputation but your long-term legacy. “At some point, you recognize that your power isn’t about climbing the mountain — you’re already at the top,” observes Rosalind Hudnell, chief diversity officer at Intel. “Using your power is about developing others, helping them achieve their leadership potential. They’re your legacy, and where your influence can make a real difference.”

In today’s rapidly changing business environment, no one person can maintain both breadth and depth of knowledge across fields and functions. But with a pocketful of the right protégés, you can put together a posse whose expertise is just a quick call away, who will burnish your brand and build your legacy.

The “All or None” Team-Based Approach to Coronary Artery Disease

By simultaneously targeting nine goals for managing coronary artery disease (CAD), rather than addressing each one in isolation, Geisinger Health System has fostered team-based delivery of care and has greatly mitigated risk factors for its patients with CAD.

The Problem

Coronary artery disease (CAD), the number one killer of both men and women in the United States, is caused by a complex array of environmental, behavioral, and genetic risk factors. When we address only a subset of those factors as health care providers, we limit how much we can reduce a patient’s risk. But targeting all of the factors at once is logistically difficult, in part because each provider typically acts independently in delivering care to a patient.

The Solution

In 2006 we at Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System systematically reviewed evidence-based guidelines in cardiology to identify the most important health care goals for our more than 16,000 patients with CAD. In each category, goals are individualized to each patient.

controlling blood pressure

achieving a target LDL (“bad”) cholesterol level

using an angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor-blocker (ARB) medication

using a beta-blocker medication

using antiplatelet medications

routinely measuring body-mass index

getting immunized against influenza

getting immunized against pneumococcal disease

not smoking

Creating the list was the easy part. Actually addressing all nine goals for every patient was the tall order. We knew the solution would mean changing our workflows to enable each member of our care team to play his or her role in a comprehensive strategy for each patient — what we call our “All or None” approach.

The Implementation

The core idea behind our “All or None” initiative is to address the nine guideline-recommended goals as a bundle, not as discrete elements. Toward that end, we developed workflows that allow physicians to focus on complex medical decision making and to delegate simpler tasks to other team members, such as office staff, nurses, nurse practitioners, and even the patients themselves. For example, our office nurses now administer appropriate immunizations when prompted by the electronic health record. We also have protocols for nurse practitioners and pharmacists to adjust medication doses to better target a patient’s goals. This exhibit is an example of one our protocols.

The result is an approach to mitigating patients’ risk factors in which each member of the care team aids patients from a unique angle, but all are focused on the same broad goal of reducing risk for adverse health outcomes.

We also use our institution’s fully integrated electronic health record to alert each team member, at appropriate times during an office or telephone encounter with a patient, about the need to perform a necessary task, such as measuring the patient’s body-mass index or checking whether the patient is taking prescribed medications. In addition, each provider, clinic, and region (as well as the entire Geisinger system) receives monthly reports on how well their patients are reaching their goals.

As a result, at both a local and a system-wide level, we can quickly detect trends, successes, and shortcomings — and then intervene as needed. For example, we found that our successful offices often had the patient obtain laboratory testing before the office visit, so that the results could be reviewed and appropriate changes made on the spot. We have expanded such process improvements system-wide, thereby allowing us to track our patients’ needs for routine care, measure their vital signs routinely and accurately, review medication use, deliver preventive services in a timely manner, track the success of lifestyle interventions, and conduct and analyze necessary laboratory studies. Each improvement mutually reinforces the others.

The Results

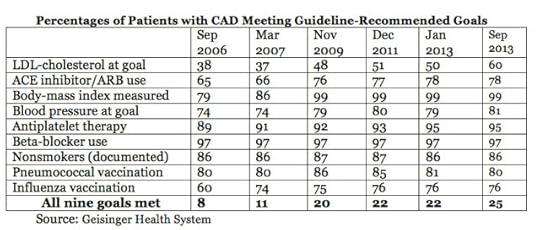

Since 2006 substantially larger percentages of our patients with CAD have managed to reach their goals. Indeed, the percentage meeting all nine goals has tripled, from 8% to 25%. Our track record on several individual goals has also improved dramatically: growth from 38% to 60% in patients reaching their LDL-cholesterol targets, from 74% to 81% in achieving adequate blood-pressure control, from 65% to 78% in use of ACE inhibitors or ARB medications, and from 60% to 76% in yearly influenza vaccination (see table).

[image error]The “all or none” approach has clearly improved the overall risk-factor profile of our population of patients with CAD. However, despite the broad effects of the initiative, we recognize several areas where we need to focus more. Here are a few examples:

Even with our success in getting patients to reach their LDL-cholesterol targets, enabling our providers to accurately identify the appropriate LDL target for each patient remains a challenge. (Those targets vary depending on the patient’s risk profile.) We are currently developing an alert within our electronic health record to identify whether each patient is at his or her accurate LDL target, whether a patient’s cholesterol has been measured during the past year, and whether the current dosing of cholesterol-lowering medications is appropriate.

We now routinely measure body-mass index for nearly every patient in our system. Initially, we had set a BMI of 25 or less as the goal. But we quickly saw that this goal is not appropriate for many patients and that the true goal is moderate, sustained weight loss. Measuring BMIs universally and having our electronic health record generate alerts for patients with high BMIs has led our patients and providers to discuss weight loss more frequently. We are getting better at recognizing what our health care team can and cannot control.

Our vaccination rates against influenza and pneumococcal disease have been almost stable for three years. We need to improve our ability to track when a patient has been vaccinated outside our organization and our capacity to offer vaccines not just at primary care clinics but also at specialty clinics.

Finally, we continue to look for novel ways to improve. These include engaging more patients, family members, and members of the health care team in our efforts, better integrating primary and specialty care, and optimizing our electronic supports.

Despite these ongoing challenges, our team-based approach to targeting all nine guideline-recommended goals for patients with CAD generated a large initial boost in our performance. Our aim is to build on our early success and take another large step in the right direction. Recent data from our parallel “All or None” effort for patients with diabetes show a dramatic reduction in heart attacks, strokes, and diabetic eye disease. We are in the process of reproducing the evaluation of these outcomes for our “All or None” approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

Make Physicians Full Partners in Accountable Care Organizations

When He Retires and She Still Works, What Happens?

My generation – the Baby Boomers – are beginning to retire, particularly the very successful ones who can afford to retire earlier. They have stayed at work late, risen early, traveled more than they wanted when their children were young, survived under different bosses, ascended through the ranks, and attained ever increasing responsibilities. Now, many of them have decided to slow down, play more golf or tennis, volunteer, and travel for pleasure. But that’s mostly just the men.

I’m seeing a surprising new phenomenon when it comes to career arcs and transitions, with women happily and successfully working longer than their husbands. As Julie, a high profile investment manager, told me, “instead of wives who raised children and managed the home waiting for their spouses to finally retire so they can travel around the world together, there are now a slew of husbands waiting for their wives to retire.”

How did that happen? In large part, this is both because the career path for women has been slower than that of their male peers and the fact that women have historically been younger than their husbands, although that is changing. A recent study of CEOs by Terrance Fitzsimmons of the University of Queensland found that male CEOs generally had full-time stay-at-home wives who could take primary responsibilities for the family and household, allowing the men to focus fully on their career. Not only did the female CEOs in the study report that they were the primary caregiver when their children were young, but that “their families took precedence over their careers.” Combining the longer time of ascent with their younger relative age can result in female executives often lagging several years behind their spouse in real career terms, hitting their professional peak when their husband has already retired or is scaling back.

This subject has been on my mind for years. At age 48, in 2004, I decided to leave my great job as a mutual fund manager to co-found an asset management firm. I was worried about how much more additional time I would need to devote to this enterprise. Our children were grown, but I was concerned about the impact of my busier work schedule on my husband. As our company expands, I occasionally revisit questions such as when I might slow down (not for quite a while!), how my husband will feel if he works less in a few years and wants me to travel and relax more. (What’s relax?)

And so I decided to ask a number of very successful women around my age, several of whom are CEOs of their companies, about this topic. I asked them to describe their husband’s work status, whether there was any friction around the amount they worked, their own plans for retirement, and what, if any, compromises they have made for their spouses’ sakes. All the women surveyed have children and almost all experienced some career interruption or slowdown when their children were young.

Sixteen women responded, and there were several common themes. All reported that their husbands were very proud of them, whether or not there was friction about their work schedules. As Alexa, the CEO of a health care services company, put it, “my husband doesn’t love when I travel and wants me to slow down, but he is really proud of me and I know he adores me.” There was a strong sense from all those surveyed that these couples had, over decades, reached a comfortable balance, where even men who had not originally expected their wives to continue to thrive professionally were now comfortable with this aspect of their marriage.

Some women had taken years off when their children were young and then gone back to full time work, with their husband’s support. As Naomi, a managing director of a major law firm, put it, “my husband totally supported my desire to work part time or not at all, and then my return to full time employment. He’s given me confidence to push ahead and tells me that he takes pleasure in my success.” Her husband also works full time and she feels no pressure to pull back her career now.

About half of the husbands were fully or semi-retired but, somewhat surprisingly, they did not exert more pressure on their wives to work less than the spouses of men who worked full time. Three common reasons emerged: they were extremely independent men; they had serious hobbies or non-profit affiliations; and they appreciated the value of their wives’ financial contribution. In all cases, whether it was a first marriage or a second marriage, these relationships had evolved over the years so that, as Clare, a CEO of a design company, put it, “We are well beyond the point of friction.”

All respondents who did feel pressure from their husbands to work less –slightly over half of my sample — said that they made compromises to accommodate their spouse. These included leaving the office earlier than they would otherwise, partaking in leisure activities that their husband chose, and making an effort to take off more time. All reported having primary responsibility for domestic tasks including groceries, cooking and cleaning, even if they had outside help fulfilling them.

Rather than resenting their spouse for interfering or being controlling, many women understood their husbands’ frustrations, perhaps recognizing the downsides of being driven. They acknowledged that non-work experiences with their spouses were important and necessary diversions, good for their marriages, and often intellectually broadening. As Trina, a senior executive at a service company, explained, “I am very sensitive about finding time with Rob (semi-retired). He encourages me to do many cultural events outside my comfort zone, which is really good for me.”

I had originally expected more women to report that their husbands, who were retired or semi-retired, would be very anxious for them to retire. What I found, however, was more negotiation and cooperation than conflict. As they move, even slowly, toward dual retirements, they seem to trust, respect, and mutually support each other, which, at least for the women, may be one contributing factor to their success.

A Three-Pronged Strategy for Avoiding Office Weight Gain

It starts with the bowls of leftover Halloween candy, brought in by colleagues too afraid of temptation to leave them lying around their own homes. What follows is a veritable avalanche of sweet and savory goodies – the seemingly endless supply of cakes, cookies, and treats that the holiday season always seems to bring to every office, everywhere.

As if it isn’t hard enough not to overeat during all those holiday parties and family dinners, how are you supposed to summon up the willpower to resist the diet-busting delectables that your coworkers insist on scattering about the workplace like landmines? In fact, it’s likely even harder to resist treats when you’re at the office: previous research has shown that when you’re using a lot of self-control to perform other tasks – something each of us routinely does while handling the stresses and challenges of work – there isn’t much left over for resisting Emily’s lemon bars or Doug’s glazed doughnuts.

If you have any hope of reaching 2014 in your current trouser size, you are going to need a strategy. Saying “I just won’t eat any of it” is not a strategy — if you leave this up to willpower alone, you will not succeed. It’s just the nature of willpower that no matter how much you start out with, its strength will ebb and flow as a function of the demands you put on it.

So try using the following research-tested strategies around the office this holiday season, and you might just be able to button your pants on January 1 without holding your breath.

Set VERY specific limits. Before you get anywhere near the cookie platter or the cheese plate, think about how much you can afford to eat without over-indulging. Decide, in advance, exactly how much snacking (if any) you will allow yourself at work that day, or at the holiday party.

The problem with most of the plans we make, including diet-related plans, is that they are not nearly specific enough. We say that we will “be good” or “not eat too much,” but what does that mean, exactly? How will you know when to stop? When you are staring at a table overflowing with delicious snacks, you are not going to be a good judge of what “too much” is.

An effective plan is one that is made before you stare temptation in the face, and that allows no wiggle room. Studies show that when people plan out exactly what they will do when temptation arises (e.g., “I will have no more than 2 cookies and nothing else”), are two-to-three times more likely to achieve their goals.

Decide what you will do instead. When you do reach your limit, what will you do then?

When you’re trying not to engage in Behavior X (where Behavior X is eating a holiday treat — or, incidentally, doing anything else you find tempting), studies suggest that one of the worst things you can do is focus solely on not engaging in X (e.g., “If want another cookie, then I won’t eat one.”) Unfortunately, this is exactly what most of us do.

In fact, researchers at Utrecht University in the Netherlands found that focusing on not doing X can result in a rebound effect, leading people to do more of the forbidden behavior than before. Just as studies on thought suppression (e.g., “Don’t think about white bears!”) have shown that constantly monitoring for a thought makes it more active in your mind, focusing on a suppressed behavior can create even greater longing.

To defeat the treat, the key is to decide in advance what you will do instead of eating it — or more generally, what you will do when temptation beckons (e.g., “If I want another cookie, then I will have a glass of water instead.”) By using water-drinking as a replacement for cookie-eating, you can move past the urge more easily.

Savor. Savoring is a way of increasing and prolonging our positive experiences. Taking time to experience the subtle flavors in a piece of dark chocolate, the pungency of a full-flavored cheese, the buttery goodness of a Christmas cookie — these are all acts of savoring, and they help us to squeeze every bit of joy out of the good things that happen to us. Avoid eating anything in one bite – you get all the calories, but only a fraction of the taste.

Try not to eat during meetings or other times when you’re interacting with colleagues. When we you are focused on conversation, odds are good that you will barely even register what you are putting in your mouth.

Eating slowly and mindfully, taking small bites instead of swallowing that bacon-wrapped scallop or stuffed mushroom whole, not only satisfies you hunger, but research suggests it actually leaves you feeling happier, too. And that, ideally, is what holiday feasting is all about.

Willpower is like any muscle – if you overtax it, it will fail you. But like a muscle, you can strengthen it gradually, over time. Strengthen your ability to resist office treats today, and tomorrow you might just find your increased willpower paying off in other areas of your work life: overcoming procrastination, keeping your temper in check, or resisting the distractions of the web when you’re tackling a particularly boring assignment. A little willpower training session now can leave you better positioned to tackle those New Year’s resolutions in January.

Inpatient Patient Navigator Program Reduces Length of Stay

At Mount Sinai Hospital, we implemented a Patient Navigator Program in our inpatient general internal medicine service as a means to help improve patient care.

The Challenge

Communication is essential for any successful relationship, including the one between a provider and her patient; however, social, economic, behavioral, and even care system barriers can weaken that connection, which may result in delayed or poor quality care. We need to adopt a measure that will enable patients to efficiently navigate through the complex health care system.

The Solution

To help circumvent these barriers, several institutions have implemented Patient Navigator Programs. Patient Navigators (PNs) are individuals who coordinate patient care, communicate with patients and their families, and oversee care transitions. There are no pre-specified training or degree requirements to become a PN — the role may be filled by registered nurses, educators who hold a Master of Science degree, and internationally trained physicians. Because PNs are not involved in the clinical care of the patient, they are available to act as the patient’s advocate and personal guide. Unlike other Patient Navigator Programs, which typically involve the management of cancer or diabetes outpatient care, we adopted a novel protocol that targets the management of complex inpatient care.

The Implementation

In June 2010, we instituted a Patient Navigator Program in Mt. Sinai Hospital’s 90-bed general internal medicine (GIM) service. Our PNs were fully integrated as members in each of our four interdisciplinary GIM teams.

PNs attended daily patient care rounds and expedited diagnostic testing, acting as a liaison between members of the diagnostic imaging, medical, and allied health teams, and the patient. PNs also made themselves available to patients and their families — they answered and clarified questions related to tests and consultations planned for the day, or reasons for patients’ admissions; PNs also coordinated discharge planning.

Under the umbrella of care transition assistance, PNs performed the following tasks:

Coordinated follow-up appointments;

Placed 48-hour post-discharge phone calls;

Provided contact information in discharge summaries (allowing patients to more easily contact a member of the care team for clarification of questions that occurred after discharge).

The Evidence

Between April 2011 and February 2012, our preliminary data suggest that patients cared for by a team with a PN (matched for age, case-mix group, and resource intensity level) experienced shorter actual length-of-stay (LOS)/expected LOS ratios compared to those not exposed to a PN. Specifically, GIM teams A and C reported an actual LOS/expected LOS ratio decrease of 0.6 % (from 89.9 to 89.3) and teams B and D reported an actual LOS/expected LOS ratio decrease of over 2 % (from 91.7 to 89.2). LOS is a common health care metric used in the evaluation of care transitions, particularly when combined with 30-day readmission rates, which we also measured. We are in the process of obtaining the data analysis.

We gathered data on patient satisfaction using the National Research Corporation Picker patient satisfaction survey data, which was mailed to patients between six and twelve weeks following discharge. We also employed a resident and staff satisfaction survey. We are still mining these data.

The Funding

The project was sponsored by a Mt. Sinai Hospital matching program, which is used to pilot and evaluate novel care delivery systems; the program is funded by physician donations, which are matched by the hospital. After one year of evaluation, the hospital deemed the project a success and allocated additional operating funds to the program.

The Next Steps

The Patient Navigator Program is still running in our GIM service. In fact, the program has expanded — it has also been adopted in cardiology, gastroenterology, and surgical oncology units. We are currently focused on evaluation of the impact of this program on patient outcomes, patient and staff satisfaction, and financial sustainability.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

Liberating Patients from Mechanical Ventilation Sooner

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

What Would Make You More Satisfied and Productive at Work?

Think about your typical workday. How often do you wake up in the morning, excited to get to work? How much time do you spend fighting traffic to get to the office? Do you run from meeting to meeting, with no time in between, as emails pile up unanswered in your inbox?

When was the last time you left your desk at midday and took an hour for lunch with a friend? How much energy do you have left for your loved ones when you leave the office at the end of the day? Do immediate demands overwhelm your capacity to do more creative and strategic thinking?

Or to put it more positively: If you felt healthier, happier, more focused, and more motivated at work, would you perform better?

Plainly, the answer is “yes,” for nearly all of us. But how much energy does your organization invest in insuring that you are healthy, happy, focused, and motivated?

Our goal at The Energy Project is to define a better way of working – in part by clarifying what isn’t working now. The assessment we’re asking you to answer here – “What Is Your Quality of Life at Work?” — seeks to understand how you’re feeling about work, what seems to influence you most, and what role your employer plays in your overall experience.

For years now, surveys conducted by firms such as Gallup and Towers Watson have shown that only about 30% of employees feel truly engaged and satisfied at work. What we want to know is: What would it take to change that, dramatically?

Our premise is that in a world of relentlessly rising demand, employers need to shift from trying to get more out of people to investing more intentionally in meeting their core needs. This means employees would be freed, fueled, and inspired to bring more of themselves to work.

I’m talking about very concrete needs: physical, emotional, mental, and even spiritual. If we are required to commute an hour or more each day during rush hour, it can’t help but take a toll on our productivity. If we work for a supervisor who doesn’t genuinely care about our well-being, much less one who manages by fear, we’re almost certainly going to feel more at risk, and less motivated.

If we’re expected to immediately answer every incoming email, we’re going to spend less time absorbed on more complex tasks and on thinking creatively and strategically. If we have no sense that the work we’re doing taps our strengths and our preferences, or provides us with a sense of meaning, we’re likely to be less engaged and productive at work. We may be relieved simply to have a job in a difficult economy, but that doesn’t mean we’ll bring our best efforts to it.

But which of these factors, and others, are most influencing our experience at work? That’s what this assessment is all about. By answering this set of questions, you’ll have a way of measuring your experience against others. We’ll ask you to evaluate yourself, your manager, and answer some questions about your habits at the office and at home. The results of the survey may provide a window for you, and your employer, into how specific organizational policies and practices influence employee satisfaction and effectiveness.

Over the coming weeks, my colleague Christine Porath, an associate professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business, and I will be analyzing the trends that emerge from your answers to this survey. We hope to identify some of the factors that most influence your experience at work. We’ll feed our conclusions back to you in posts on HBR.org.

Among the things we’re hoping to learn: The correlation, for example, between your ability to balance work and home life, and the level of satisfaction, engagement and positive energy you experience on the job. How much does the level of meaning you derive from work matter? What about the freedom to work from home, or flexibility in when you work?

What’s the influence of leaders and managers on your experience at work? And if you are a leader or a manager, what can you do better fuel your people? At the organizational level, what is the impact of the kind of space you work in, or whether or not you have the freedom to take renewal breaks or work out during the day? How does each of these factors influence your overall satisfaction and your likelihood of staying with your current organization?

Our goal, with this assessment, is to consider you as a whole person, by asking questions across multiple dimensions of your life. Through your answers, we hope to better define, for you and for your employer, the ingredients of a sustainably, highly-engaged, high-performing workplace. To make that possible, add your data to this effort and take this short assessment.

China’s Bad Bet on the Environment

It was a moment for the Chinese people to savor. For nearly two years, they had called on Beijing to take action on its air pollution crisis. Websites exploded with pictures and data, documenting the terrifying health and economic costs of the pollution: a drop in life expectancy of 5.5 years in the country’s heavily polluted north and an estimated $112 billion in labor and health care costs in 2005. Experts and citizens shared information, expressed views in polls, and demanded change. Finally, in September 2013, faced with mounting social discontent, Premier Li Keqiang announced a sweeping new plan to try to address the country’s air quality problems.

Environmental activism in China is not new. For almost two decades, the environment has been at the forefront of civil society development. There are more than 3,500 formally registered environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) — and at least that many un-registered — throughout the country. Chinese citizens routinely protest against local governments’ environmental practices. In 2013, the environment surpassed illegal land expropriation as the largest source of social unrest in the country.

Despite this history of citizen activism, however, Premier Li Keqiang’s policy announcement stands out as one of the first times that the central government has directly responded to popular pressure, and it may be one of the last for some time. It is far from certain that this victory for Chinese people power will be repeated in the near future.

Rather than embrace these signs of greater political participation, President Xi Jinping and the rest of China’s new leadership are working to constrain civil society. They have taken aim at the Internet, passing regulations to limit the ability of the Chinese people to share information and to undermine the influence of the country’s most popular billionaire bloggers (including some involved in clean air campaigns).

China’s leaders have also moved to contain the role of environmental NGOs by advancing an amendment to China’s environmental protection law that will bar those groups from bringing lawsuits against polluters. If it succeeds, only 13 organizations in the entire country will be able to launch environmental lawsuits in court. As China’s top environmental lawyer, Wang Canfa, has noted, the regulation is “driving public litigation into a dead end.”

This does not mean all civil society is dead. Environmental NGOs are continuing their work on a range of politically neutral issues like environmental education and energy efficiency. And the Chinese people are still taking to the streets to protest environmentally harmful projects. During the latter half of 2013, for example, Chinese citizens forced local governments to cancel a range of large-scale projects, including a 2000MW coal plant, a uranium processing plant, and an incinerator. As the new government chips away at the foundations of civil society, however, it is unclear how much longer officials will tolerate such demonstrations.

As China sorts out its path forward, the rest of the world will largely be a bystander — but not one without significant stakes in the outcome. There is excitement at the prospect that the new leadership recognizes the importance of the environment. This recognition could translate into greater opportunities for multinationals engaged in environmental protection work, new partnerships for international NGOs, and new commitments to global environmental challenges, like climate change.

But at a more profound level, China’s leaders appear to be betting that their approach to environmental governance — top-down, command, and control — can work. They’re also betting that developing the fundamentals of good environmental governance — transparency, rule of law, and official accountability — pose too great a risk. That has been the bet for more than 60 years. It is hard to believe that China’s leaders think that where they are now on this issue is where they really want to be.

China’s Next Great Transition

An HBR Insight Center

Jack Ma on Taking Back China’s Blue Skies

What Business Can Expect from China’s Third Plenum

The Three Reforms China Must Enact: Land, Social Services, and Taxes

Is It Time to Be Skeptical on China?

Increase Accountability Without Incurring Distrust

Introducing more accountability into an organization is never easy; all too often the people you are trying to make accountable interpret your initiative as a sign that you don’t trust them. It’s a problem I encountered frequently in the post-soviet companies that the private equity fund I advised invested in.

A particularly striking case in point was the experience we had with the local management of a large flour mill we had acquired in Romania in a privatization tender. They were suspicious from the get go; Western investors in post-communist countries were known for firing incumbent managers and installing their own people.

So although we left the old management intact they questioned the motives behind every organizational change we attempted. It was, however, the introduction of the standard internal auditing system used by our investment partners, the largest flour mill in Greece, that really got them going.

We tried in vain to convince the chief of the Romanian mill’s Accounting Department that the Greek Stock Market required its member companies to use the system. He just kept on insisting that we didn’t trust him and his team and the system was our way of ensuring that the locals wouldn’t cheat us.

The whole local management team shared this sense of humiliation and injury, and this was starting to have a serious impact on morale. No matter what we said, it was impossible for us to convince them that the auditing system we wanted to install was identical to the one used by the Greek flour mill and, therefore, had nothing to do with whether or not we trusted them. As a local friend expressed it: “the more you try to convince them with words, the more suspicious they become.”

So we stopped talking and started thinking and acting. I began by sharing with them my own monthly report on the flour mill’s performance to the fund’s management team in Greece. There, they read for themselves my assessment of their prospects and problems, along my proposals on how best to move forward. None of what they read was particularly surprising but they felt flattered that I would share such an important document. Most importantly, it made them feel trusted. Building on this, I started to ask for advice on what to put in the report, which they took, as intended, as a signal that I valued their experience.

After about four months, I took the three top managers in the Financial and Accounting Department to the Head Office of our partners in Piraeus for a week. There, they could see for themselves that the company did indeed use the system in all its mills and that auditors appointed by the Greek Stock Market Authority reviewed the results of every mill. We also asked the Greek mill’s financial managers to explain that accountability systems like this did not signify a lack of trust but actually served as a means of increasing it.

This visit not only enabled our Romanian managers to better understand the relationship between accountability and trust, it also fully convinced them of our sincerity. They appreciated the open, collegial, and hospitable way their Greek counterparts treated them. At the same time they gained a great deal of respect for their new owners’ large, modern, well-managed mill and started to feel pride in belonging to the same company. They came away convinced that we were determined to keep the local team on and to help them become an integral part of the larger group.

When we got back, I asked the local team to start submitting their reports to me along the lines of my own report. At first they found it hard to openly admit in writing their omissions and failures! Nevertheless, they made a start and over time they began to recognize the considerable gains they would derive from monitoring their own productivity in the reports. They learned that by looking at themselves in the mirror and seeing themselves as they really were, they would better understand what they needed to do in order to keep improving.

How Credit-Worthy Is America, Inc.?

Last month, the government was partially shut down for 16 days at a cost of $24 billion and we came within two days of running out of money to meet our debt obligations. The current government funding will run out in January. The American people and the wider world are skeptical that the US will be able to get its fiscal house in order.

But setting aside political brinkmanship, can we objectively analyze how the country is doing financially? Rather than looking at debt figures or dollars spent in a vacuum, we need to also judge the US economy on a relative basis. After all, businesses sit in markets, which means they do well or poorly only compared to others in the market, as well as the market in general. In financial terms, and especially with regards to credit, governments are no different. As the CEO of a credit business, I’m in a unique position to take a look at how the US actually stacks up.

We’re doing exceptionally well compared to other governments. Several agencies rank government creditworthiness, and according to all of them, the US is pretty darn good: Moody’s rates us at the top of the scale with an AAA rating. Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. to AA+ last year, but only two of the world’s ten largest economies rank better (Germany and the United Kingdom). The next two largest economies, China and Japan, are both ranked lower. In addition, Japan has roughly twice the debt to GDP ratio of the United States.

Of course, governments are notoriously inefficient, and many say that the United States would fare better if it were run more like a business. If the government were a business, how would its credit rating look? Many factors come into play to determine credit and credibility scores. Scale is important, measured by factors like annual revenues and number of employees. As a large entity, the United States would have high marks here. Longevity is also important. Its 237-year history gives the US an incredible legacy for a company (albeit less than most other nations). Late payments and defaults hurt a business credit rating most, but the US government has always paid its debt on time and has never defaulted, despite congressional posturing.

What about the amount of debt itself? When comparing the United States’ balance sheet to a household budget, as most politicians do, the government looks severely over-leveraged. But from a business perspective, it’s just not so. Many successful companies borrow money to fund growth. Sometimes, they borrow a whole lot of money. IBM borrows about 2x what it makes annually; GE and Dupont each borrow about 3x. JP Morgan Chase’s debt-to-income ratio is a hefty 50-to-1. The United States debt-to-GDP ratio, in comparison, is only about 1-to-1. The US is relatively unlevered.

As long as borrowed money is used to fuel growth, going into debt is usually considered smart business. In the United States, we have historically increased government spending (even if it meant borrowing) in times of depression or recession to fuel the economy. Some may argue that recent government borrowing was not spent in a way that promoted growth, but the bottom line is that increasing the national debt, in itself, does not create a credit problem. With the economy growing again, the US can sustain more debt.

How about credibility? Credibility scores use data other than financials to determine whether a business deserves the confidence of its partners and customers. The main components of these scores include stability, transparency, and trustworthiness. Generally, the United States would rank well on those components relative to other countries. But there is a fourth component where the government would fall short. It is sentiment, and it’s indicated by items such as ratings and reviews, news coverage, and other qualitative measures that determine what people think about an entity. This is where perception becomes an important reality, and the U.S. government clearly has a big perception problem.

This one negative point should not overshadow the larger reality. But it is something Congress might want to keep in mind as we approach the next round of budget negotiations.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers