Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1515

November 14, 2013

Your Genes May Predispose You to Claiming Too Many Sick Days

A study of more than 2,000 Swedish twins reveals that people’s approval or disapproval of everyday dishonest behaviors has a genetic component, says a team led by Peter J. Loewen of the University of Toronto. For example, genes accounted for 26% of the research participants’ views on the acceptability of illicitly avoiding taxes and 42.5% of their attitudes toward claiming unnecessary sick leave. Other factors affecting the participants’ attitudes included their individual experiences and environments, the researchers say.

Understanding Chinese Consumers

After spending 15 years in North America, I returned home to China and found some fascinating phenomena. A bottle of 2006 Penfolds Bin 389 cabernet, which costs $37 in the U.S., is about $77 in Beijing. Huggies diapers cost about the same in the U.S. and China, but the ones in China are of lower quality. Why are these global brands using different marketing strategies in the U.S. and China? Why did eBay, so successful in North America, fail miserably in China? The key to answer these and many other questions lies in the understanding of Chinese consumers, their characteristics, and their changing needs. Below are just a few considerations:

Chinese Consumers Are Price Sensitive, but Brand Conscious

Although this seems to be a puzzling mix, the price-sensitive but brand-conscious Chinese consumer reflects an important duality. Price wars occur on a regular basis. This is clearly hurting companies, but nobody can afford not to participate in a price war, as price is often the determining factor for Chinese consumers when making purchase decisions.

At the same time, the Chinese are very brand conscious, as is shown by their fondness of luxury brands. According to Bain & Co., the luxury sales market in greater China is expected to grow by 6-8% this year, to exceed $35B — making it second only to America.

Why are the Chinese price sensitive and brand conscious at the same time? The key to understanding this puzzle is to appreciate the Chinese culture, where face and social status are crucial. If a brand can signal a higher social and/or economic status, Chinese consumers would be happy to pay a premium. If it doesn’t, they become very price sensitive.

For brands that can signal status, such as luxury watches and wine, the price is usually at least two times more in China than it is in the West. However, for brands that people use in private, and thus do not have the signaling function, MNCs are producing comparably priced items for the Chinese market, yet with lower quality than those sold in the West. Glad’s Press’n Seal plastic wrapping paper costs about the same in the U.S. and in China. However, in China, you can press, but it doesn’t seal! In the short run, these global brands can still profit in China, but such a myopic strategy will eventually damage the brands as consumers in China become more informed.

There’s a Lack of Trust in China

EBay requires buyers to pay first and then wait for the item to be delivered. This model works in a society where the trust level is high. However, there is a serious lack of trust in China right now, so to ask buyers to pay first without seeing the product is a hard sell. That’s why eBay failed so miserably in China. Taobao, on the other hand, came up with a different model. It introduced a third-party payment system, namely AliPay. Buyers will pay the money to this third-party account owned by Alibaba (Taobao’s holding company), and only after they have confirmed receiving the products, Alipay will transfer the money to the seller. This model effectively solved the trust issue, and was immediately successful.

Food safety is another big concern in China right now. For example, the Chinese do not trust local milk brands due to the notorious milk contamination incident in 2008. As a result, there is a high demand for foreign milk brands. In China, I pay double the price of what I used to pay for milk in North America.

China’s One-Child Policy Means Kids Play a Central Role

Due to the one-child policy, many young Chinese families now have one child surrounded by two parents, four grandparents, and often times a nanny and a driver. Thus, the entire industry providing kid-related services is growing at an unprecedented speed, and parents are usually much less price sensitive when buying for their kids than for themselves. For example, a one-hour art or sports class for a 4- to 10-year-old costs around RMB200 (about $33) in Beijing, a price much higher than what parents would be willing to pay for themselves. Similarly, Best-Learning English, an after-school program that has American teachers teach English to school-age kids, can cost up to RMB28,000 ($4,700) per year per child. And the demand is so high that the school now has six centers in Beijing alone, and 24 in China. Tuition at established international schools in Beijing costs twice as much as those in the West, yet the demand far exceeds the supply. Understanding what parents want for their kids, be it English education and creativity cultivation, would be crucial for MNCs to compete in China.

Chinese Consumers Are Becoming More Informed, More Sophisticated, and More Active

In 2012, Chinese took 83M foreign trips, up by 18.4% from the previous year. These experiences, along with technology development and social media channels, have helped Chinese consumers become more informed and sophisticated. For example, many Chinese travel overseas to buy branded products, as it is much cheaper than in China. Similarly, Chinese are now looking for subtler ways to signal their status by avoiding brands that have loud logos.

At the same time, Chinese consumers are becoming more active in protecting their rights. In 2011, some consumers discovered a problem with a Siemens refrigerator, and started to complain to the company. However, Siemens refused to acknowledge the problem at the beginning. Then Luo Yonghao, a celebrity in China, organized various activities to boycott the brand, which caused a crisis for Siemens, and they eventually had to acknowledge the mistake and apologize. But the damage had already been done.

China has changed. It’s no longer just a place for companies to outsource their production. The market is big, diverse, and has tremendous potential. Thus, “Made in China” is being replaced by “Made for China”. In order to really thrive in this market, foreign companies have to truly understand the needs and changing characteristics of Chinese consumers, and build quality products and services to meet these needs.

China’s Next Great Transition

An HBR Insight Center

China’s Bad Bet on the Environment

Jack Ma on Taking Back China’s Blue Skies

What Business Can Expect from China’s Third Plenum

The Three Reforms China Must Enact: Land, Social Services, and Taxes

November 13, 2013

Research: Cubicles Are the Absolute Worst

My work station is an invading overlord. Belongings march across the long desk I share with several other editors, spilling out of my space and incurring into the neutral zones abutting my colleagues’ work areas. To the east, legions of books, papers, and sticky notes advance, led by a squadron of glass paperweights. To the west, my cotillion of tote bags, receipts, and forgotten coffee mugs blocks any retreat.

But fortunately, thanks to recent research by Jungsoo Kim and Richard de Dear at the University of Sydney, I know that my mess probably doesn’t bother my coworkers all that much. In fact, of all the myriad annoyances of office life, workspace cleanliness bothered scarcely 10% of workers — although workers in offices like mine, where there are no partitions, were bothered slightly more. (Perhaps because there is no Great Wall to contain the advancing hordes of a colleague’s stuff.)

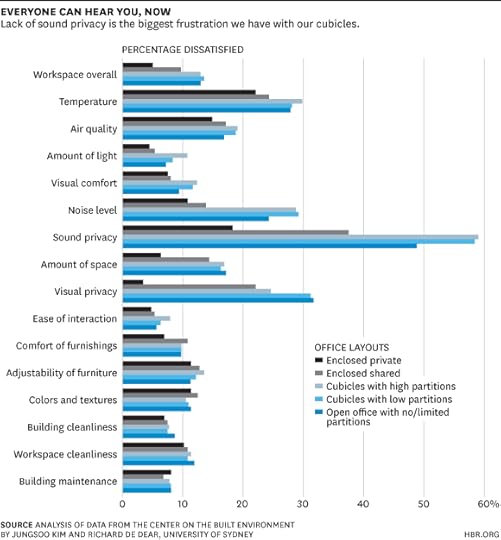

What probably gets under my colleagues’ skin much more is how noisy I am: the muttered curses when my computer gives me the blue screen of death or the impromptu phone calls with authors that end up lasting an hour (sorry guys!). A full 30% of workers in cubicles, and roughly 25% in partitionless offices, were dissatisfied with the noise level of their workspaces.

The worst part, according to the data, is that these office workers can’t control what they hear — or who hears them. Lack of sound privacy was far and away the most despised issue in the survey, with 60% of cubicle workers and half of all partitionless people indicating it as a frustration. (Researchers guess that the partitionless people are slightly less bothered by it because at least they can see where the noise is coming from, which gives them a sense of control — no matter how illusory. Based on my own partitionless office, I’d also guess a lot of those workers are listening to music on headphones to block out distractions.) Other frustrations included lack of visual privacy and temperature. There was no data collected for intrusive smells.

Given that other studies have shown we only spend 35% of our time at our work stations, though, I it seems reasonable for a cost-minded manager to assume that we should just abolish the office, despite its popularity with workers. Make everything modular. Let the collaboration flow.

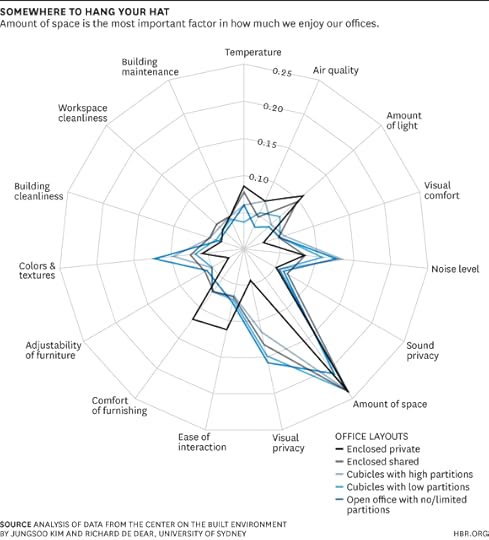

Not so fast. Previous research, cited by Kim and de Dear, has already shown that “the loss of productivity due to noise distraction… was doubled in open-plan offices compared to private offices, and the tasks requiring complex verbal process” — the most important tasks, you might argue — “were more likely to be disturbed than relatively simple or routine tasks.” In this paper, Kim and de Dear show that this loss of productivity is not offset by increased collaboration. “Ease of interaction” was barely an issue — less than 10% of all office workers cited it as a problem, no matter what kind of workspace they had. In fact, people in enclosed offices found it even less of an issue than workers in cubicles and workers in open layouts. (Perhaps because enclosed offices obviate the all-too-common challenge of finding a private place to talk.)

And when the researchers looked at the data a different way — using a regression to calculate what was not only most frustrating, but how important each frustration was to a worker’s overall satisfaction — the single most important issue was a lack of space. That held true no matter what kind of office you had — an enclosed office, a cubicle, or an open layout.

The bottom line: workers in enclosed offices were by far the happiest, reporting the least amount of frustration on all 15 of the factors surveyed. Workers in cubicles with high partitions were the most miserable, reporting the lowest rates of satisfaction in 13 out of those 15 factors.

I’m left with the conclusion that Virginia Woolf was right: what one really needs is simply a room of one’s own. Stained coffee mugs, teetering stacks of books, and all.

High-Stakes Decisions Are Rarely Dispassionate

One day this month, the first Tuesday of November, brought plenty of news for students of decision-making to ponder. There were big election results in the US: new mayors in New York and Boston, one governor newly elected in Virginia and another re-elected in New Jersey. Meanwhile, in business, BlackBerry’s CEO stood down as an offer to rescue the ailing company fell through, while a high-profile investor, Bill Ackman, posted strong returns even as one of his most notable investments — taking a short position on the nutrient supplier Herbalife — garnered controversy.

At the heart of all these events were decisions made by people. One day’s news serves to show how much decisions can vary — and how different some of them are from the sorts of decisions so often studied in laboratory research.

As I discuss in more depth in an article in the current issue of HBR, much of what we know about decision making comes from neatly devised experiments, where subjects make choices between clearly identified alternatives. Would you pick the 12-month subscription for $24.95, or the 24-month subscription for $39.95? That’s a fine way to capture the dynamics of consumer choice, where shoppers respond to the options placed before them. We also know a lot about the way people make judgments under uncertainty, like predicting the movement of a stock price or the performance of their favorite football team. For these and many other judgments and choices, we know that people make common errors. The lesson, by now repeated over and over, is to beware of common biases and to avoid them. Nothing good comes from wishful thinking.

That’s fine for many ordinary examples of choice and judgment, but it falls far short of grasping the nature of so many consequential decisions, whether in business or politics.

Let’s come back to the examples above. If you’re casting a vote for governor or mayor, you’re making a choice much like a shopper selecting this or that item. You pick from the options on the ballot, but — other than a casting a write-in vote — can’t change the options on the ballot. Just as important, you can do no more to improve the quality of the candidate you select than you can change what’s inside the box you put in your shopping cart. You hope Bill de Blasio will be a good mayor, but if you’re one of the one million New Yorkers who cast a ballot, you can’t do much to influence his performance in office.

For the newly elected mayor, the reality is different. The decisions he will make in office are not simply about things he cannot influence. The nature of political leadership is about getting things done. As the late Richard Neustadt, Harvard professor and expert on the presidency, once advised: The power of the presidency is the power to persuade. No political leader, not even the president, can lead by decree or executive fiat. It’s imperative to mobilize others to get things done, and that calls for effective persuasion. In turn, persuasion depends on projecting confidence and inspiring others. An entirely objective and sober assessment is insufficient. It’s also crucial to infuse others with optimism, and even to hold beliefs that may seem somewhat unrealistic – but which if believed can be brought to fruition.

What then, is the distinctive decision making skill of the successful politician? It’s the ability to recognize how decisions vary and to respond appropriately to each. When it comes to making assessments about things we cannot change, like economic trends or an approaching storm, this means taking a dispassionate view. When it comes to running a successful campaign, it means incisively appraising rivals, staking out positions that will be attractive, warding off rivals. And perhaps most importantly, when it comes to leading others, it means charting a course that infuses confidence and inspires supporters to achieve desired ends.

As for the business examples noted at the outset? The decisions they make, too, are considerably more complex than the simple choices so often studied in decision research. As CEO of BlackBerry, Thorsten Heins did not merely need to choose a viable strategy based on an accurate, unbiased appraisal of BlackBerry prospects. For his decision to turn out to be the “right” one, he had to inspire others to make that potential materialize. Decisions by his predecessors about product features and software standards had led to a deterioration of US market share from 50 percent to just 3 percent in four years. The performance of any decision by Heins depended on his ability to reassure customers about the viability of his product, by now far behind rivals like Apple and Samsung, and to boost investor confidence for the future. Alas for Heins, it proved to be too great a task.

A different kind of decision faces Bill Ackman, a Harvard Business School graduate of 1992 and lead investor of Pershing Square Capital Management. Most investment decisions involve taking positions in assets — whether equities or bonds — that we cannot directly influence. That’s the nature of portfolio investment. Ackman’s fund, on the other hand, is an activist investor that seeks to influence the management of companies in which it invests. Often these are long positions, where Ackman bets that underperforming assets can be more efficiently managed, perhaps through seats on the board and influence over management. At times, Ackman’s fund takes short positions, where he may not have direct influence on the company but through public pronouncements raises questions that may lead the share price downward — indirect influence but a powerful force nonetheless. Either way, the essence is to influence outcomes, not merely make decisions akin to consumer choice or buying a share on the open market.

Decisions run the gamut from discrete judgments and choices where the emphasis is on accuracy and objectivity, to instances where we can and must exercise control over outcomes. Research has taught us a great deal about many kinds of decisions, but we should be careful not to apply the lessons elsewhere without appreciating the differences. In particular, we should recognize that, for a newly elected mayor, or the chief executive of a troubled firm, or an activist investor, the task is to shape outcomes, often by shaping perceptions and mobilizing others. And in such cases, effective decisions involve much more than the exercise of dispassionate judgment.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Making Decisions Together (When You Don’t Agree on What’s Important)

Stop Worrying About Making the Right Decision

Managing “Atmospherics” in Decision Making

The Six-Minute Guide to Making Better High Stakes Decisions

Three Questions to Consider Before Deciding Where to Locate Your Start-Up

About twice a month I get the opportunity to sit in on Seed and Series A stage startup pitches in Washington DC. However, the unfortunate truth is that those talented founders I see aren’t generally in the right city to build their businesses. In the first article in this series, I showed some striking numbers to stress what many inferred: there are real costs to locating operations outside of a startup super-hub (San Francisco Bay, New York, or Boston). The short version: it’s just plain harder to get funding, sell your business, or simply survive outside of the super-hubs. In the second article of the series, James Allworth and I proposed some solutions for policy makers.

But this noticeable bias in outcomes, however significant, is not going to stop ambitious entrepreneurs from building businesses where they live today. There are many good reasons to do so: family roots, a sense of neighborhood responsibility, existing professional networks, and more.

There are also great success stories to encourage us. In the past few years alone we’ve seen Zappos flourish in Las Vegas, Sendgrid experience massive growth in Colorado, and RightNow put Bozeman, Montana on the start-up map with a $1.5 billion dollar sale to Oracle.

Being disadvantaged in pursuit of your goal is not the same as resigning yourself to failure. So the question is, if things are naturally skewed against your favor, what can you do to improve your chances? I can’t give you an answer — every city and every company are too different — but I can suggest three questions can help you figure it out for yourself.

What’s your city’s advantage? No entrepreneur should start a business because he’s interested in being an entrepreneur. He should start a business because he’s found a real problem in the world and desperately wants to solve it. But with that in mind, you can look for the problems you’re better positioned to solve because of — not in spite of — your location.

Today, Silicon Valley is the consumer and enterprise software capital of the world. Fortunately for would-be entrepreneurs everywhere else, the Valley doesn’t hold that claim in every industry (yet). Finance has homes in New York, Hong Kong, and London. Energy is still the domain of Houston and Dubai. The Fashion landscape is dominated by European firms. The list goes on and on. Most cities have something that they are particularly good at.

For entrepreneurs starting up outside a super-hub, understanding where their geography has an advantage is key. For instance, in the DC area, we have an immense number of security and intelligence experts working for the government. The talent pool is better than anywhere else in the world. So for would-be entrepreneurs in the area, pursuing an opportunity in that leverages that expertise becomes more and more appealing.

When you focus on your area’s advantages, you’ll find it’s easier to overcome some of the challenges I’ve discussed previously. You’ll find your existing professional network is more valuable in helping get your business off the ground. You’ll not only find customers and employees more easily, you’ll likely find funding as well. For DC’s cybersecurity entrepreneurs, venture funds like In-Q-Tel & CORE Capital have emerged to fund such endeavors. They have specific expertise that allows them to compete with the likes of the Silicon Valley elite for a narrow subset of deals.

How can you get exposure? Finding talent and financing isn’t the only hurdle to overcome on the road to startup success; it’s the first of many. Exposure is another key ingredient. Exposure to customers, incumbents, and competitors all drive success. Exposure to customers helps us understand the job we’re trying to complete and guides us towards building the right solutions. Exposure to incumbents helps us understand what we’re competing against and also facilitates the relationships that ultimately drive acquisition.

And most importantly, exposure to competitors instills fear. The fear that you’re falling behind. The fear that your products are inferior. The fear that you’re two heartbeats away from obsolescence. That fear is the motivator that keeps you driving forward. As Paul Singh, one of the early partners at 500 Startups said, “[entrepreneurs] want the urgency that comes with feeling just a little behind other entrepreneurs near [them].”

In superhubs, this sort of exposure tends to be common. Outside of superhubs, it’s less readily available. The good news is that the world is an increasingly small place. It’s possible to bridge your startup with communities in California, New York, and Boston. Companies including (Paul’s) Dashboard.io., Angellist, Crunchbase, and more all help entrepreneurs stay connected to each other even when at distance. The proliferation of startup conferences facilitates networking. And plane tickets to San Francisco or New York aren’t that expensive. If you take advantage of everything at your disposal, you can make certain you’re well exposed.

What will set your business apart? Entrepreneurship is one of the hardest challenges you’ll ever pursue. There will be elated highs and devastating lows. All along the way you’ll be scrambling to move faster than your competition. Being in a superhub helps you to maintain pace because of your access to resources. When you’re outside of a superhub, ask yourself what edge you can create for your business that others in the valley can’t replicate?

For example, Tony Hsieh built a family at Zappos. From engineer to call center employee, people loved being at Zappos. That culture and a sense of ownership caused his employees to work harder, stay longer, and be kinder to customers than any other competitor. It was a painstakingly thoughtful endeavor, but it paid off. The question I would ask is whether that’s possible in the Valley today. Maybe, but there is no doubt that an embedded engineering hierarchy and an intrinsic appreciation for jumping ship to pursue the next big idea will make it more challenging.

If you’re outside of a super-hub, ask yourself what you can do to sprint faster. Maybe it’s culture. Maybe it’s public-private partnership. Maybe its offering more complete service and maintaining profitability because you’ll tap into lower wages and taxes. No one can tell you want to do to create your edge, but it is important that you figure out how you can. Your competition has too much tailwind to sit idly by.

One bonus question: Are you sure you don’t want to move?

Moving might not be easy. But it is one of the simplest things you can do to improve the odds that your business takes off. If you’re about to devote your professional life to building a business and ready to sacrifice the blood, sweat, and tears it requires, seriously consider the last question. It’s easily one of the most important.

Fix the Handful of U.S. Hospitals Responsible for Out-of-Control Costs

In May 2013, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released CMS Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) inpatient data that contain discharge information for 100% of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries using hospital inpatient services. This data shows what more than 3,200 hospitals in the United States were being paid for the most frequently performed 100 inpatient procedures. The variations were extraordinary. Some hospitals in the New York State were being paid 40 times as much as the world-famous Mayo clinic for some treatments.

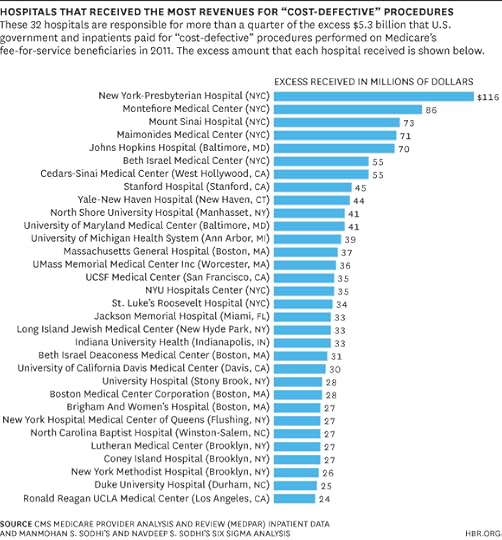

This kind of variation is understandably a huge cause of concern at a time when health care costs are widely seen to be spinning out of control. Our research suggests, however, that the data contains a silver lining: The bulk of excess costs to CMS and inpatients for all the procedures — a total of $5.3 billion above the average across all hospital by procedure — are highly concentrated in just a small number of hospitals.

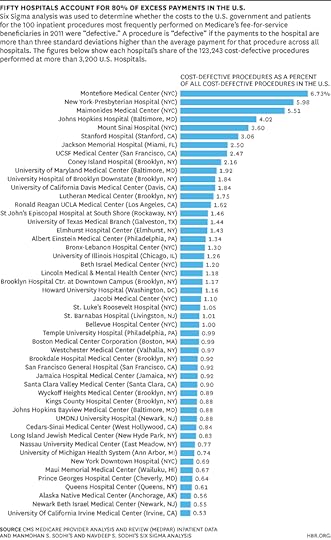

When we applied the techniques of Six Sigma analysis to the CMS data, we found that just 32 hospitals — less than 1% of the hospitals in the data — accounted for about 25% of the excess accepted charges. (Hospitals determine what they will charge, or bill, for items and services, and CMS then decides how much of that amount is appropriate and will be paid.) A handful of hospitals in New York State accounted for nearly half of them. Add some hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland, and some in the cities of San Francisco, Stanford (Palo Alto), and Los Angeles in California, and the figure goes to nearly 80%. If the excess is that highly concentrated, it is likely that significant efficiency gains can be achieved with relatively little effort.

The discipline of Six Sigma measures the variability of a process attribute, say, costs or prices, in terms of number of standard deviations away from the average. Indeed, the term Six Sigma refers to the three standard deviations (or “sigmas”) below and three above the average for the bell-shaped normal distribution. In this context, the definition of a ‘defective’ cost to patients and CMS is being a statistical outlier: that is, a procedure at a hospital is cost defective if the portion of the charge the CMS and patients paid is more than three standard deviations higher than the average across all hospitals for that procedure.

The CMS data provides summary information on nearly 7 million records of the top 100 most frequently performed procedures performed in 2011. Of these 100 procedures, the top two types alone account for more than a tenth of all procedures performed: major joint replacement (6.1%) and septicemia (4.6%). With such high frequencies, one would expect a more-or-less standard cost to CMS and patients across hospitals. However, for major joint replacement (procedure 470) the cheapest hospital received $9,000 per treatment on average while the most expensive received $39,000; for septicemia (procedure 871), total accepted charges ranged from $7,500 per treatment on average in the lowest-cost hospital to about $44,000 in the highest-cost one.

By carrying out this analysis on the full dataset, we found that fewer than 2% out of the nearly 7 million procedures — 123,243 to be precise — were ‘defects’ in the sense that the average total payment received per procedure in a particular hospital was a statistical outlier across all hospitals for the respective procedure. This means the amount paid to the hospital for the procedure was more than three standard deviations higher than the average payment for that procedure across all hospitals. Note that the standard deviation is already quite high as reflected in the wide variation in costs to CMS and patients; so to be an outlier is quite something.

(A simplifying assumption necessary for using the CMS data is that each hospital charges the same amount for any particular procedure for each time it carried out this procedure was carried out in this hospital in 2011. Getting rid of this assumption by dealing with all procedures at a given hospital individually would not change the overall results, though.)

The exhibit below shows the 50 hospitals responsible for 80% of the total 123, 243 cost-defective procedures across all hospitals in the United States in the CMS data. As a result, these hospitals received extra revenues.

The exhibit below lists the 32 hospitals (less than 1% of all the hospitals in the data) responsible for more than a quarter of the $5.3 billion extra paid for cost-defective interventions and the excess amount for those procedures that each received.

Owing to the skewed distribution, a majority of the hospitals in the country have below-average accepted charges. Moreover the providers with the most egregious costs to CMS and patients are concentrated in such locations as Brooklyn (nearly 15% of all defects), Bronx (about 9%) and New York City (slightly less than 9%). Providers in New York State alone are responsible for half of all the cost-defective procedures followed by California (about 18%) and Maryland (about 11%).

The conclusion we draw from this is that before fretting about fixing the health care system in general, the U.S. government and the hospitals themselves should consider engaging in a Six-Sigma-type analysis every year for continuous improvement. They can identify the tiny minority of hospitals — or areas within a hospital — that are enormously expensive across many procedures they perform and need better understanding of what is behind their extraordinarily high accepted charges. It may well turn out that many of these excess charges levied by these few hospitals can be significantly reduced simply through better management.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Saving Academic Medicine from Obsolescence

Liberating Patients from Mechanical Ventilation Sooner

Constraints on Health Care Budgets Can Drive Quality

A Role for Specialists in Resuscitating Accountable Care Organizations

Southwest May Start Charging for Baggage, and That’s a Good Thing

Southwest Airlines has long been a darling of consumers. With low fares, a fun inflight experience, and an irreverent corporate attitude, what’s not to love? And while most airlines now charge for baggage, in its maverick way Southwest makes the fact that it allows 2 free checked bags per passenger the centerpiece of its advertising campaign.

So it came as a surprise when its CEO, Gary Kelly, recently hinted that it may join the pack and start charging for baggage. While this is a big change for the airline, more importantly it signals a new pricing strategy trend for the future. After all, if the airline that many consider to be a consumer champion can get away with nickel-and-diming consumers, why shouldn’t other companies do so, too?

Nickel-and-diming customers (or as I prefer to call it, a la carte or unbundling) is by now a pretty standard way airline companies can unleash new profits. All of the ancillary fees related to flying from one location to another (telephone reservation, baggage, early boarding, preferred seats, food, pillows/blankets) really do add up. IdeaWorks, an airline revenue consultancy, estimates that consumers will pony up $42.6 billion worldwide for these extras in 2013.

A close friend recently shared his feelings about all of these extra fees. “I’d rather just pay one price for everything – I hate feeling gouged for every little thing,” he complained. And while I’m sure many travelers share his feelings, it’s also important to consider the alternative. I recently booked an impromptu round trip flight from Boston to Los Angeles for $300 – that’s incredibly reasonable. If airlines were to bundle all of these extra services into one base fare, my ticket price would have been significantly higher for things (like pillows) I may not even want.

In reality, a la carte pricing provides a low cost option to enjoy a product as well as allows customers opportunities to pay if they want more. On my trip to Los Angeles, for instance, I have the options to pay a one-time fee of $25 for a telephone reservation as well for each segment of my flight: $60 for 2 checked bags ($120 roundtrip), $99 for a “choice seat” ($198 RT) $10 for priority boarding ($20 RT), and $10 for an on-board meal ($20 RT). That adds up to $383 roundtrip!

When it comes to a $300 build-from-a-base fare vs. a $683 all-inclusive price – I’ll take a la carte pricing every day.

After several years of being cautious with their pricing, companies are now trying to charge more. A la carte pricing is a key strategy to consider as it provides two important benefits:

Broadens a Customer Base. A draconian across-the-board price increase forces customers to make an uncomfortable “take it or leave it” buying decision. Inevitably, some customers will decide to “leave it” – resulting in a loss of sales. The beauty of a la carte pricing is if a price boost is too much, customers can make it more affordable by foregoing a few options. The result is a more robust customer base ranging from the thrifty (those who just buy the base product) to high rollers (“I’ll take every single extra you offer”).

Compassionate Messaging. During this era of economic struggle, consumers are sensitive to price increases. As a result, the message supporting a price increase rollout is critical. It’s important to offer both the full bundle (at a premium) as well as a la carte prices. By offering both, you are communicating to customers that while prices have to go up (for the full bundle), you are being respectful of their financial circumstances by providing choices to reduce price. I’ve found this simple message engenders goodwill with customers and as a result, reduces the risk of backfire.

Of course, there’s a fine line in deciding how many services to make a la carte. One such company that may have ventured too deeply to the dark side is Spirit Airlines. In 2012, for instance, Spirit’s average ticket-revenue-per-passenger was $75 while the average a la carte fee it collected per passenger was $51.39. This focus on collecting extra fees has generated considerable consumer ire. That said, the financial results are impressive: Spirit’s revenue increased by 88% from 2009 to 2012.

Whenever I pitch the notion of a la carte pricing to managers, the reaction is predictable: palpable fear and groans of nickel-and-diming customers. But this strategy actually has plenty of upside benefits. And let’s face it: If Southwest Airlines can move to a la carte pricing, your company can too.

What Problem Will You Own?

On the days I’m smashed up against an assortment of characters on the New York City subway, I sometimes play a game.

I imagine someone yelling, “What’s your problem?!” It’s a question I’ve heard in this situation plenty of times before but instead of causing a kerfuffle, I picture a different reaction: An elderly gentleman across the aisle uses his cane to stand up and proudly declares, “I’ve dedicated my life to addressing poverty.” A young woman raises her hand, clears her throat, and announces, “I care about gender inequality.” A teenager pulls out his ear buds and says, “My problem is racial profiling.” Soon, everyone around me has announced a problem that they are personally dedicated to.

The world would look drastically different if we spent more time identifying a problem to own, rather than fighting for more space, more time, or more money in our own little part of the world.

At Echoing Green, a nonprofit organization that supports young people to dedicate their lives to improving the world, we’ve learned that if you want to make a difference, you need to own a problem. You must make it yours to solve.

There are three steps to doing this: identify your problem, prioritize it, and then work to solve it with the resources you have.

Identify

Of course, many of us care about multiple issues, and can’t pick just one. Problems, after all, are interconnected. But sometimes you have to dive deep into a specific one if you want to solve it.

How do you know what is your problem to own? The answer is, well, you just know. Your heart, not your mind helps you identify it. You feel it before you know it. You have a visceral reaction when witnessing the problem: Your skin crawls, your hair stands, your eyes twitch, or you feel unimaginable empathy for those affected. Or rage. Or elation when there’s progress. And you can’t let it go.

It creeps up on you when you’re daydreaming, or keeps coming up in conversations with friends.

Unfortunately, we haven’t been taught to spot these moments of connection so, more often than not, we let them go by.

But that wouldn’t happen in a world where we all own a problem.

If you’re not sure, try filling in this simple sentence: _____ is what matters. Think of the moments when you feel great emotion experiencing, learning about, or witnessing a particular problem. Fill it in with just one problem: Education. Sanitation. Prison reform. Gender equity. One that matters the most to you.

Prioritize

To truly own a problem—you need to prioritize it. After all, saying “yes” to what matters most always means saying “no” to other things. For instance, if you want to make a real difference in the lives of homeless youth, you may need to make some tough choices — cutting out weekend activities so you can volunteer or upsetting your boss when you tell her that you have to leave work on time to attend a fundraiser. Owning a problem means it’s part of who you are and it’s what you do. It doesn’t need to be a full-time job. It just has to have significance in your life.

Solve

To fully own a problem, you can’t just care about it and prioritize it. You have to do something about it.

If you don’t know what role you might play in solving something as big as gender inequity or poverty, you can start by asking yourself: What resources do I have access to that can help solve this problem?

The way in which you own a particular issue can evolve over the years; in fact, it should.

Take Raj Panjabi, CEO of Last Mile Health. The problem that really matters to him is health inequality in his home country of Liberia. Here’s how he came to own this issue.

He experienced a moment of obligation when he was a child. As Liberian rebels neared his town, his mother, his sister, and he rushed to a plane and escaped, but he watched as many of Liberia’s poor, including mothers with children on their back, were fought back by soldiers as they tried to get on the plane. This image of those left behind — almost certain to die — stuck with him. He knew this was his problem to own.

As the war raged in Liberia for 14 years, he worked hard, trained as a doctor, and ultimately joined the faculty of Harvard Medical School. He could have led a comfortable, successful life, totally disconnected from Liberia. But he knew he had go back to his home country — now desperately trying to heal post conflict — to address the inequality he saw as a young boy. So he gave up the life of a high-achieving doctor and returned.

Of course he saw many problems when he arrived but there was one that he had the resources and the know-how to address — health. There were only 51 doctors to care for the entire country. If you got sick in a city, you stood a chance. But if you got sick in a remote village, hundreds of miles from the nearest clinic, you could die anonymously. He felt his expertise in health and his empathy from knowing the problem could help solve this particular aspect of the inequality. So he worked with local experts to create Last Mile Health, which gives village health workers the training, equipment, and support they need to save lives. These workers have carried out over 100,000 patient visits bringing health care to rural Liberians in the most remote villages — the majority of whom would not get care if Raj hadn’t owned this problem.

Next time you’re squeezed in between strangers on public transportation try playing your own game. Imagine who on the bus will own which problem and what impact that may have on your city, your country, the world. And don’t forget to ask yourself one key question: What will you say when you stand?

Are You Among the 14% Who Always Tell the Truth?

In a laboratory experiment to test people’s willingness to lie to a partner in a game, 14% of people always chose to be truthful, even if lying would have benefited them, and 14% chose to lie whenever they stood to gain, according to a team led by Uri Gneezy of the University of California, San Diego. The rest reacted in variable ways to incentives, sometimes lying and sometimes not, except for one participant who always lied, regardless of circumstances.

What Strategists Can Learn from Architecture

Managers routinely claim that their strategic planning process creates large, detailed documents, but often little else. It’s as if the process serves no purpose other than to create the plan, and execution is somehow separate.

An approach that we think might work better would be to treat strategy making as if it were a design process. We’re not the first to propose that strategy borrows from design; in HBR articles, Henry Mintzberg drew the analogy with the potter throwing a bowl and Roger Martin has made an explicit connection with design. But the aspect of design we want to focus on here is a bit different.

The key feature of the design process that interests us is the concept of “levels of design”, a notion that the creation of a design goes through a series of levels of increasing complexity and detail.

When an architect designs a new house, for example, he does it in stages of increasing detail. At the first level, he sets out a few basic principles that he and the client agree on: the kitchen should face east to catch the morning sun, the car port should be close to the kitchen to help unload groceries, the patio should face the South, there should be three reception areas on the ground floor, etc.

At Level 2 he draws a rough sketch of the building. It might include a basic plan for each floor, a plan of how the building might sit in its plot and a view from each side.

Level 3 is a scale blueprint with accurate measurements, detailing invisible but essential aspects, such as which walls are load bearing, and how the plumbing and wiring will be routed. It might include suggested positioning for the main bits of furniture and some important material choices, such as clay roof tiles or a wood floor in the living area.

Level 4 is the quantity surveyor’s list of materials and quantities: the number of clay tiles needed or the yards of copper wire. Final decisions are made about power points, about the taps in the bathroom and the colour of the kitchen wall, often delegated to lots of different specialists.

Level 5 involves the many issues that come up as the new house is being built. An extra power point is needed for the wi-fi router. The chosen wood-fired burner requires a bigger alcove than planned.

If we used the concept of “five levels of strategy”, we might be less likely to find ourselves with fancy plans and little action. We would still need strategic planning documents, but we would recognize them for what they are: rough sketches at Level 2. If we decide not to follow the strategy, we can leave it at this level. But, if we want to execute the strategy, we will realise that we need to develop plans at Level 3 and Level 4.

A Level 3 plan identifies the main organizational units responsible for different parts of the strategy and the operating model that links these organisational units together. For each unit, the plan specifies the outcomes expected, the timeframes, the way the unit will work with other units, any constraints on the unit and the resources available. The sum of outcomes at Level 3 will achieve the objectives defined at Level 2.

A Level 4 plan specifies the people, the money and the time needed for each sub-task within each unit. It also explains how units will continue with existing activity and the sequence to take on the extra tasks required by the strategy.

Just as the work of the quantity surveyor often throws up issues for the architect to resolve, so too will Level 4 plans raise issues to be resolved at Levels 2 and 3. Strategic planning should, therefore, include an iterative process for dialogue between levels. This requires a concept of levels of strategy and clarity about the work at each level. In the military, the dialogue process is called back-briefing. Interestingly, in strategy work, we do not have a good label for this activity.

Finally, Level 5 planning is about the inevitable adjustments that need to be made as events unfold. The money is not available when expected. Critical people leave with little prior notice. The competitor reacts aggressively to the plan. A supplier is late.

Sometimes events cannot be handled by adjustments at Level 5. Changes are needed at Levels 4 or 3 or 2. This is when clarity about levels is again helpful. Knowing when events require a Level 5 or a Level 2 response ensures that strategies do not wander off course unnecessarily or fail to correct course when circumstances demand it.

Maybe, just maybe, an awareness of levels of strategy work will help organisations do better strategic planning. It can’t very well do a lot worse.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers