Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1511

November 20, 2013

How Chinese Companies Can Develop Global Brands

China leads all emerging markets with 89 companies on the latest Fortune Global 500 list of the world’s largest. Yet it does not have a single representative on Interbrand’s list of the top 100 global brands. Also, while China’s outward-bound foreign direct investment (FDI) has grown from an annual average of below $3 billion before 2005 to more than $60 billion in 2010 and 2011, only one third of Chinese companies have seen international revenue meet expectations, according to Accenture.

To many skeptical consumers in developed markets, Brand China still means lower quality. As has been the case elsewhere in Asia, companies in China traditionally focused on asset-intensive industries and low-cost manufacturing and paid little attention to intangibles such as brands and human capital. To become major branded players away from home, Chinese companies must address their challenges in three strategic ways.

1. Seek partnerships with Western brands. Whether through joint venture, merger or acquisition, the right partnership can give a boost to a brand’s tangible offering or intangible appeal. A significant part of telecom equipment maker Huawei’s leap from regional player to global leader, for example, was due to its partnerships with Motorola in 2000, 3Com in 2003, and Symantec in 2008. Western brands also want access to China and recent global market turmoil has exposed many targets for astute Chinese brands.

2. Redesign the organization. Hierarchies can be debilitating when those at the top of the pyramid do not understand the challenges of those on the ground. A local, adaptive culture, not just presence, is vital for Chinese brands to make the right decisions overseas. Beijing-based telecom security company NQ Mobile has gone so far as to create a separate headquarters in Texas for its developed-market business, managed by an American co-CEO and entirely comprised of American employees. Hiring foreigners in high-profile roles, such as former Google VP Hugo Barra at the helm of electronics company Xiaomi, can also create a more open line of communication with governments who must be won over as well.

Boardrooms at home in China must also begin to reflect a cross-section of cultures and skills. Since positioning is vital in new markets, today’s boards must include Chief Marketing Officers, not just directors with operations or finance backgrounds.

3. Rebrand from the inside out. “Branding” is a widely misused and misunderstood term in China (and Asia), where most executives believe it refers to how a company uses its logos, packaging, and advertisements. Not that a simple redesign or name change can’t do wonders for a Chinese brand overseas. Since messaging app WeChat was re-branded from Weixin to appeal to international audiences, it doubled its overseas users in just six months and parent company Tencent holdings became the fastest-rising Chinese brand, according to Interbrand.

If they intend to flourish overseas in the long-term, however, Chinese brands must pursue more than just superficial redesigns. When Accenture asked 250 senior executives of Asian companies expanding overseas to compare their source of competitive advantage today and in three years, 55% cited high quality products and services, while 47% cited high-value innovation. Only a small minority thought low-cost operations would be an advantage in three years’ time.

Chinese firms must shift toward high-value, high quality, innovative products and services – a path that requires patience and persistence as Japanese and Korean firms spent many decades cultivating their international brands. Samsung is one of the best examples.

Overcoming China’s own barriers. The Chinese government also sometimes stands in the way of building brands overseas. Politicians in the U.S. have effectively barred Huawei from bidding for telecom contracts there, claiming that Chinese authorities could commandeer its equipment for cyberespionage. That may say more about the xenophobia of U.S. politicians than anything else, but other obstacles are more clearly Beijing’s doing.

Government measures intended to cool an overheating economy, such as tightening loans and freezing IPOs, are holding back companies that need capital to grow. Some have turned to overseas exchanges — like 58.com (China’s Craigslist) which recently went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

Chinese marketers also know that building a global brand in the social age requires a presence where they can reach overseas consumers — yet popular global social media sites such as Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook remain blocked by the Great Firewall. As a result, more Chinese companies are requesting special permission to create Facebook pages which will only be seen outside the mainland.

Chinese businesses are slowly becoming more attentive to the power of branding in capturing consumers and returning larger profits on their investments. Instead of wearing themselves down on razor-thin margins to compete with the next supplier, firms are looking to increase returns by investing in their brands. To remedy the knowledge gap and transform their image abroad, successful Chinese brands must seek help from the outside through foreign partnerships, decentralizing and diversifying leadership, and cultivating a new perception of Brand China.

China’s Next Great Transition

An HBR Insight Center

The Chinese Steamroller Is Already Sputtering

The Politics of China’s Economic Adjustment

China Needs a New Generation of Dreamers (and New Dreams)

Understanding Chinese Consumers

Cherish Your Ever-so-Slight Dissatisfaction

People who are just slightly dissatisfied at baseline might have an advantage over others in getting themselves out of negative situations such as unemployment, suggests Annabelle Krause of the Institute for the Study of Labor, in Germany. For example, she found that highly happy and unhappy people were about 40% and 17% (respectively) less likely than their average-happiness peers to have found new positions one year after losing their jobs, possibly because these personality extremes can lead to loss of resilience and motivation in adversity. A slight dissatisfaction, by contrast, can serve as a motivator to achieve more and earn more money.

What to Do When Good News Makes You Anxious

No one in a position of responsibility wants to confess to “the jitters” or “sweaty palms.” Dislocate a shoulder and you can cry for sympathy all you want. But if you’re worrying incessantly about the quality of your work, letting on about it can feel risky — and generate even more anxiety.

In my experience with executives, nothing about anxiety is as disruptive as its propensity to pop up when least expected, or in contexts where anything but anxiety seems appropriate: after a positive outcome like a promotion, a plum committee assignment, or stellar quarterly results. Unfortunately, those who don’t know how painful these bouts of anxiety are usually trivialize them: Women suffering anxiety after success were, until recently, diagnosed with a “fear of success.” When men suffered these symptoms it was called “happiness anxiety.” Actually, it’s neither.

People forget that good news is often a double-edged sword, stroking egos and enhancing status (not to mention financial rewards) with one edge, while imposing performance demands and social isolation with the other. I’ve seen newly promoted managers declare they will stop climbing the career ladder rather than risk falling victim to The Peter Principle – their pay-packages be damned.

Over 2,000 years ago, a brilliant Greek philosopher identified the cause of most anxieties and mood disorders: “Men are disturbed not by things, but by the views they take of them.” The approach of this early “therapist” — the ancient Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus — today might be classified as “Cognitive Behavior Therapy” (CBT), a highly effective treatment for pit-in-the-stomach malaise and comparable symptoms. Knowing, for example, that a recent promotion has you fretting about every piece of work you do, a therapist certified in CBT can help you “think straight” about performance expectations and rid yourself of anxiety.

Another approach is adaptive therapy, where behaving in adaptive ways converts negative thoughts into positive ones. Interventions of this sort are as grounded in empirical science as CBT is: The so-called James-Lange theory of emotion, developed independently by two 19th century psychologists, William James and Carl Lange, demonstrates that emotional reactions are responses to a behavioral experience, not the cause of them. The classic example: “I know I fear the bear because I’m running away from it.” Or, to take a work example that stems from good news: “I know I’m afraid of my new boss because ever since I got this promotion, I always go to lunch from 1:30PM-2:00PM when he does his daily walk around the office, so that I don’t have to deal with his drop-in.”

Acting in non-anxious ways can help you conclude “I’m capable of handling this.” For instance, you might confront your fears with a determined “game face” — holding your head high with a laser-focused gaze, or assuming a power pose. Once you learn to do this across a variety of situations, your emboldened behavior will not only lead to diminished anxiety but, in addition, yield myriad interpersonal rewards from colleagues who appreciate these manifestations of strength.

Forcing yourself to live through — in your imagination — the worst possible consequences of your fears is another tactic for reducing anxiety born of irrational fears. Take that new boss you hide from by planning your lunches with NASA-like precision. You’re avoiding a feared encounter with imagined negative consequences. But avoidance doesn’t improve your ego strength or on-the-job competence.

A more adaptive approach would be to address your anxiety as follows:

Grab a pad and provide as many answers as possible to the question, “What would happen if my new boss drops into my office?”

Don’t stop “answering” until you have 5 possible consequences.

For each outcome you’ve listed, do the “yes, but” test to see if it’s real or a fantasy. For example, you tell yourself, “Well, he could tell me my new team has been complaining about our revised budget goals, and he’s really disappointed in me…” Using a “yes, but” counter-argument you would be forced to say, “Yes, he could be disappointed, but even if he is, isn’t it better to know it now than to find out later?”

If you repeat this over and over – listing fears and “yes, butting” them out of your life— you might never look forward to a drop-in from the boss, but you’ll be able to eat with colleagues and not get ill in anticipation of an unwanted visit.

Another self-help technique you can use to rid yourself of “crazy” anxiety is to put yourself back in control with the, “Who’s to blame?” test. It works like this:

You know you act in a manner that others call “paranoid”— you worry that important people dislike you or are out to get you. Perhaps you reached out to said boss about said budget revisions and he hasn’t replied to your calls and emails. Now you’ve got the “no news is bad news” jitters big time. When you are feeling anxious about an ambiguous situation, go through this checklist that I call S.T.O.P.:

S. Who do you know who feels the same as you do? Most of us would be anxious in this situation. Realizing that can help allay your concerns. Conversely, you might realize that you’re worrying about something not a lot of people would fret over, which can also help you gain perspective.

T. Are you torturing yourself over this issue? Ask yourself if the amount of energy you’re expending worrying over the issue is proportionate to the seriousness of the issue itself. If you’re not sure, ask a trusted friend for a reality check.

O. Is this anxiety ongoing? Is there a pattern here? Do you always freak out when you don’t get immediate feedback? If so, you bring anxiety to your interactions with the person you want to hear from. He is not doing a thing to upset you.

P. Do you pester people to allay your fears? If so, this is a likely reason why they do not communicate with you in ways you want them to (i.e. quickly).

If you reach letter “P” in this analysis, you’ll likely be in a position to start asking yourself, “Why am I doing this to me?” which will position you to stop needless worry about this issue. To address others, just extrapolate from this model to fit the instigator and content (e.g. “Co-workers think I’m stupid”) of your anxiety.

The beauty of these techniques — essentially mechanisms for helping you realize that you are catastrophizing about events— is that they work infinitely better than “self-talk” in which you tell yourself you are strong and can cope. The reason why is that such self-assurance often feels disingenuous. Analyzing realistic worst-case scenarios and assessing the level and source of your anxiety is a logic-driven method for concluding, “I’m making myself go mad!”

Mark Twain once observed, “I’ve had thousands of problems in my life, most of which never actually happened.” Take an active approach to relieving anxiety, and you’ll stop being haunted by problems that will likely never come to pass.

November 19, 2013

When the Truth Is Your Only Chance

A few months ago, Paul Franco* took a job working part-time for a company in the healthcare industry. At the time, Paul told me he thought the company had tremendous potential, both in the marketplace and for him personally.

So I was a little surprised when he called me, exasperated. “I think I’m going to quit,” he told me.

So we discussed it. The pros for staying were plentiful: he is free to work on his own time, from wherever he wants, doing what he loves, towards a goal about which he cares. Also, he’s making good money and a difference — both of which matter to him.

Sounds great, right? So what are the cons? There’s only one, really: His boss, the CEO/founder.

“He’s all over the place,” Paul told me. “Shifting from one vision to the next. He’s unfocused, unclear, unrealistic, and, most disturbingly, he’s burning bridges with potential investors as well as colleagues. He even reneged on a commitment he made to me, which I had already extended to other people. He’s hurting the business and I’m worried about my reputation by affiliation.”

Should Paul quit? Even with all the seductive pros, the answer seems glaringly obvious: Of course he should quit. And not just because the CEO is unfocused. He should quit because no opportunity — no matter how badly you need the money — is worth losing your reputation.

I was itching to share my advice but I held back long enough to ask one last question:

“Have you told the CEO what you’ve told me?”

He hesitated. “Not really. Not so clearly.”

Now my answer was very clear though not the one I had planned. “Leaving now,” I said to him, “is a big mistake. I have a much better idea.”

Paul is in a situation I see all the time: An organization or a relationship is either stagnating or deteriorating and no one knows what to do to fix it. Just in the last week alone I’ve heard people talk about unsatisfying managerial relationships, languishing business results, and unhappy marriages. The only two choices seem to be to live the depressing reality of an unpleasant rut, or leave.

Instead, I suggest a third option: risk truth.

Remember when you were a kid, playing ball, and the ball got stuck up in a tree? At that point, you had three options: You could stare at the ball, with growing frustration (stay in the job), you could walk away and play a different game (quit), or you could find a stick long enough to reach the ball and knock it out of the tree.

Think of the truth as that stick.

If Paul doesn’t risk the truth, nothing changes. If he leaves, he will end up in a similar position again — we always do — and then he’ll leave again. The ball will remain stuck in the tree.

But that stick of truth shakes things up. He’ll have to stretch beyond his own comfort to share his observations with the CEO. He’ll have to think about it, work on it, take his share of responsibility, and communicate carefully.

But however uncomfortable that is, it’s not the scary part. The scary part is the uncertainty of the CEO’s reaction. The CEO might lash out. Or sit in denial. Or fire Paul.

Here’s the crucial thing though: There’s no real risk for Paul, because he was going to leave anyway. Paul has nothing to lose.

And the upside? It’s limitless. He might be able to turn around the company. He might develop a deeply trusted relationship with the CEO. He will undoubtedly increase his ability to engage in difficult conversations. He will know he did what he could for the benefit of the company. And, most of all, he will shake things up.

Anything else he tries — political maneuvering, avoidance, stepping cautiously around the CEO’s challenges, speaking poorly about the CEO behind his back, defending the CEO even though he doesn’t believe it, living with things as they are — is soul-sucking and will maintain the status quo.

The truth is his only chance. Not talking about something keeps the ball in the tree.

This is true of any stuck situation. Languishing business results? Asking the hard questions and getting to the uncomfortable truth of the obstacles – whether the truth leads to people or process or something else — is the only chance we have of stimulating a turnaround. The unhappy marriage? Share the truth and either things will get better or worse — but at least they’ll move.

The biggest problem most of us have isn’t that things are bad, it’s that they’re not changing. The truth changes things.

The hard part is moving through the mystery of what will happen when the truth is on the table. It’s that fear of the unknown — the risk it represents — that leads us to keep the truth hidden.

So how do we get over that fear? It’s simple and hard: courage.

First, you need to ask yourself the hard questions about what you really see, think, and feel. Are you projecting? Blaming someone else for your issues? Or seeing things as they really are? In other words, seek the truth. Be honest with yourself, first.

Then, once you feel confident about what you believe — or even if you don’t — tap into your compassion and care for the other person and be direct. Don’t sandwich your truth with apologies, soft-pedaling, and contradictions. That would be hitting the tree so softly that the ball never comes out. On the other hand, don’t whack the tree so violently and indiscriminately that all the branches break off. Share your perspective as “Here’s what I see, feel, think.” Be clear and own it. Then leave time and space for the other person or people to respond.

Finally, let go of your need to have the other person reply in any particular way. You’ve done your part by being clear, compassionate, and honest. You can’t control the rest. But your stick of truth will have shaken the ball free of the tree.

I recently got a call from Paul who sounded more excited about his work than I had heard in a long time. He had spoken with the CEO. “This is what I see you doing that is making my job harder,” he told him. “This is what I hear you saying and how it feels to be on the receiving end of it. This is what I saw you do last week that hurt the company’s reputation.”

Initially, Paul was disheartened. His boss received it well but Paul felt like it was all talk. Not much changed.

Now, though, a month later, things do seem to have changed. Some of it was the CEO — he seems to know more about his limitations and is sticking closer to what he does well.

But it’s not just that. Paul has changed too.

Speaking the truth loosened him up. He’s not as frustrated as before. He’s more committed, more willing to take risks with the CEO and in other areas of his job and life. Courage begets courage. That’s one of the gifts of speaking the truth.

“Today was an amazing day!” he told me on the phone. “The CEO is setting up great meetings for me and I’m doing really well in the meetings. We’re both in our sweet spot.”

*Names and some identifying details have been changed.

Defend Your Research: Working Long Hours Used to Hurt Your Wages — Now It Helps Them

Youngjoo Cha, an assistant professor at Indiana University, and Kim Weeden, professor at Cornell University, report in a new paper that the wage premium for working long hours is on the rise – and that rise is perpetuating the wage gap between men and women.

But doesn’t it make intuitive sense that those who work longer hours would get paid more money? Hasn’t that always been the case?

Professors Cha and Weeden, defend your research.

Cha: In the first 15 years of the period we studied, from 1979 to the mid-1990s, labor force survey data [from the Bureau of Labor Statistics] show a wage penalty for working long hours, even after adjusting wages for education and experience. Workers who put in 50 or more hours per week earned less, per hour, than comparable workers who worked a standard 40-hour workweek. This makes sense if you think about salaried workers, who are not directly paid for overtime: if you are putting in longer hours at the same salary level as a coworker, you’ll be paid less per hour. You may be rewarded indirectly, if working long hours puts you at the head of the line for a promotion or if you get non-monetary benefits out of your job. But in much of the 1980s and early 1990s, long work hours did not necessarily translate directly into high hourly pay.

Weeden: One of our key findings, though, is that this overwork penalty decreased over time. By the mid-1990s, overworkers received higher wages per hour compared to full-time workers with comparable levels of education, experience, and other attributes. By the end of the 2000s, overworkers earned about 6% more per hour than their full-time counterparts. This shift from wage penalty to wage premium implies that overworkers experienced a much sharper increase in their hourly wages than regular full time workers.

OK but… doesn’t it make sense that if you work longer hours, you’d get paid more? Could it be that we’re now just paying people for the overwork they’re putting in?

Cha: Remember, we’re talking about hourly pay, not total pay. We are now at a point where each hour of labor by an overworker is paid more than an hour of labor by a comparably educated full-time worker. Is that fair? That’s a bit of a philosophical question, and it depends on whether these workers are truly more productive on an hourly basis than their full-time counterparts, or whether employers are using long work hours as a way to rank workers or as the basis for assumptions about how much a worker is contributing to the bottom line. In the new knowledge economy, particularly where work is organized in teams, productivity can be very hard to observe directly. In the absence of direct measures of productivity and contributions, employers may use the number of work hours as a signal.

What if the people who are overworking are changing – becoming more educated or more productive – relative to those who only work full time? Would that explain why they are earning more, on an hourly basis?

Cha: The changes in the attributes of people who work long hours today versus 30 years ago may be part of the story, but it’s not the entire story. First, all our models adjust for education and labor force experience, and some of our models adjust for occupation as well. The rising wage returns to overwork are not solely due to, say, the fact that today’s overworkers are more likely to be highly educated or to work in high-skill occupations than overworkers in the past.

Second, in our data, we see that the overwork wage premium is larger in the occupations where overwork is more common. This pattern is consistent with the argument that in some occupations, workers are expected to put in extremely long hours, and people who fail to meet this expectation are penalized in their relative hourly pay.

What kind of occupations are we talking about?

Weeden: Overworkers today are concentrated in the so-called “greedy occupations,” which was [sociologist] Lewis Coser’s term for occupations that require undivided attention, loyalty, and time commitments from their members. The standard examples of “greedy occupations” are doctors, lawyers, engineers, even academics. Our data show that the increase in overwork through the 1980s and 1990s, and the increase in the hourly wages for overwork, was most pronounced in these types of occupations.

Cha: Managers also fit into this category. They are also under pressure to work longer hours, to demonstrate both professional competence and loyalty to the company. More generally, the steepest increase in overwork in the 1980s and 1990s occurred in highly skilled professional and managerial occupations. In these occupations, the culture is such that employers and employees alike buy into the notion that the “the ideal worker,” to borrow Joan Williams’s term, is someone who works all the time, as if family life doesn’t exist.

That’s a good segue to the major finding in the paper: that this wage premium for overwork is part of the reason that women still make less money than men do. Walk us through that connection.

Cha: Even as the percentage of workers who put in 50 or more hours per week rose through the 1980s and 1990s, the gender gap in overwork – the difference between the percentage of men who overworked and the percentage of women who overworked — was fairly stable. Men continued to overwork at higher rates than women, and so the rising wage returns to overwork disproportionately went to men, pushing apart men and women’s average wages. Our analysis shows that if the hourly wages for overwork had stayed the same throughout the period, the overall gender wage gap would have decreased by about 10% more than it did.

Weeden: This overwork effect, in an accounting sense, was quite large. In fact, it was strong enough to offset the countervailing effect of women’s rising educational attainment. The end result was that the gender wage gap didn’t narrow as much as you might expect if gender differences in education and labor force experience alone affected it.

Cha: Another interesting piece of the story is that professional and managerial women are less able to take advantage of overwork wage premiums than their male peers. As I showed in an earlier paper, professional and managerial women are especially likely to have overworking spouses. These spouses’ long work hours limit their contributions to housework and caregiving. Although these couples may earn enough money to hire others to do some of these tasks, there’s still a very strong culture of intensive mothering in the US. Professional and managerial women are in a bind, in that they can’t be both ideal workers who put in long work weeks, and ideal mothers, at least as our culture defines them.

If the wage premium for overwork has gone up over time, then why do we see a drop-off in the amount of people working more than 50 hours a week during the 2000s?

Cha: We don’t have a clear answer for that. It could an effect of the “jobless recoveries” of the last two recessions. Other survey data show that many workers in the low-wage labor market would prefer to work longer hours than they do, but can’t find jobs that offer longer hours. Or, it could be that attitudes toward work hours are changing, particularly among younger workers, and more employees are seeking some balance between work and family life. But this pattern certainly needs to be studied.

How does this fit into the broader story of widening income inequality across the economy?

Weeden: Well, some of the growth in income inequality is due to three interconnected trends: the decline of manufacturing, the growth of the service sector, and the waning power of unions. As a consequence, there are fewer opportunities for workers in manual and service occupations to earn overtime. Instead, low-wage workers have to cobble together multiple part-time or full-time by low-paying jobs, working longer total hours in order to earn the same wages.

It’s possible that overwork also played a role in the growth of income inequality between the top and the middle of the wage distribution. As the wage returns to overwork increased, particularly in the professions and managerial occupations, the workers who are able to put in long work hours pulled away from their full-time counterparts. In a counterfactual world where men and women are equally likely to put in long work hours, this could have increased overall wage inequality without affecting the average gender gap in wages. Our paper, by contrast, shows that this change in how we reward long work hours had a marked effect on the gender gap in wages.

The Chinese Steamroller Is Already Sputtering

For his new book The Myth of America’s Decline, Josef Joffe spent a lot of time studying and thinking about China — the current leading challenger to U.S. economic and political supremacy. While many portray China’s economic and political ascent as an epochal event, Joffe sees the country as yet another “fast riser” following a path previously traveled by Germany, Japan, and the Asian “tigers.”

What that means, in Joffe’s view, is that however impressive China’s rise has been, the country now faces many of the same hurdles that slowed down the other rising nations — plus some obstacles of its own making. Joffe is the publisher-editor of the German weekly Die Zeit and a faculty member at Stanford University. I talked with him earlier this month; what follows are edited excerpts from our conversation.

What does China have in common with Germany, Japan, Taiwan, etc.?

These models across cultures are uncannily alike. They all obey the same three or four principles: Overinvestment, the counterpart of which is oversaving; export über alles; underconsumption; and an undervalued currency. Plus collusion between state and the economy in various ways.

These countries all had amazing growth rates in the beginning — the Germans up to 8%, the Japanese even higher — then they all came down. So I had to ask myself what was happening here, and I concluded that in all cases that famous old law of diminishing returns begins to bite and every additional unit of fixed investment yields less additional revenue.

That is the case in China too. Lo and behold, the growth rate is down from 12% to 7%. Part of it may be cyclical, but the other part is structural. I mean, look at the other Asian countries. They came down from double digits to zero in the case of Japan. High flyers always come down to a normal rate.

A pretty obvious difference between Japan and China is that for Japan to become the world’s leading economic power, it would have needed a per capita income twice that of the U.S. With China there is a reasonable argument that even if they remain much poorer than the U.S. they’ll eventually have a similar-sized or larger economy.

But that means you have put together 1.3 billion very poor people. And look at the demographic curves these guys are facing. The United States is going to be the youngest country 40 years out, save for India. A young country means you’re going to be more economically dynamic — old people don’t bust ass. I think by 2020, the Chinese are going to account for one-fifth of the world’s population and one quarter of the world’s pensioners.

But at some level, this catchup story, it is a success.

Damn right.

All these countries went from being poorer to much more affluent. You look at Korea or Taiwan, and if China is even able to keep going at 7% for a couple of decades …

But there’s a tipping point, if you look again at those little tigers, when growth suddenly flattens. That’s what we call the middle-income trap. All kinds of things happen when you’re in the middle-income trap. You have a rising middle class, and the rising middle class no longer allows you to extract so much surplus from it for the benefit of the state. Investment goes down, social security begins to move to the fore, etc.

Singapore has escaped the middle-income trap …

You cannot generalize from small countries. You know about the PISA tests? The hype is that the U.S. is not doing so well. Actually they’re not doing badly. They’re in the upper bound of the middle. Who’s on top? Shanghai. China as such chose not to be tested like all the others. So you take a choice apple and test it against the barrels of everybody else. But if you were testing Palo Alto or Bethesda or Cambridge, Mass., against Shanghai, guess what would have happened? I want to see Shanghai competing with Palo Alto High.

You say in the book that going forward it’s a lose-lose situation for the Chinese regime.

Democracy or enduring authoritarianism is not good for growth — for different reasons.

An authoritarian regime is good for catch up …

Very good at the beginning — Stalin, Hitler, they were great.

When you look at China, what do you see as the best plausible outcome — for China?

They’re caught in this double bind, which we just mentioned. Certainly the regime does not want to be unseated. So they’re going to hold on to power. Especially since they had that traumatic experience of the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen. At the other extreme, in order to maintain growth in this post-industrial knowledge-based economy they have to loosen the reins. They have to allow for freedom of expression and freedom of research. But that’s very hard to do. You’re talking about the one-party system.

I think they’re going to do dilemma management, and keep their fingers crossed that they’ll have enough economic performance to maintain legitimacy. But I’m now at the point where I’m with Yogi Berra: “Never make predictions. Especially not about the future.” All I’m saying is that the streamroller is sputtering already.

None of this says anything about grand strategy, international behavior. That is a very subtle contest between the United States and China. It’s not like against Russia or Nazi Germany. China is not a revolutionary power. It’s a revisionist power. Revisionists just want a bit more for myself, or a lot more for myself. Revolutionaries want to overturn the table.

I’m also looking at sources of future strength. What’s enduring? Demography is one thing, and that’s where the Chinese are really in bad shape, whereas the United States is getting younger. Why? Immigration, plus whatever else makes Americans procreate more often. Immigration, it turns out, is probably the single most important asset you can acquire in our world. It’s no longer coal or even oil. And there the U.S. at this point beats everybody hands down.

China’s Next Great Transition

An HBR Insight Center

The Politics of China’s Economic Adjustment

China Needs a New Generation of Dreamers (and New Dreams)

Understanding Chinese Consumers

China’s Bad Bet on the Environment

You’ve Got the Information But What Does It Mean? Welcome to “From Data to Action”

“The numbers don’t lie.”

You hear that all the time. Even if it’s mostly true, the numbers can be slippery, cryptic, and, at times, two-faced. Whether they represent findings about your customers, products, or employees, they can be maddeningly open to interpretation.

With big data getting ever bigger and infiltrating more and more parts of your business, the need for ways to understand the numbers’ meaning is becoming more acute. As Tom Davenport of Babson College and MIT writes in the current issue of HBR, companies must “fundamentally rethink how the analysis of data can create value for themselves and their customers.”

In this series, “From Data to Action”, researchers and practitioners explore the fast-changing landscape of data, show how you can learn to tune out most of the noise to focus on the all-important signal, and translate your new knowledge into bottom-line improvements. Scott A. Neslin of Dartmouth’s Tuck business school puts it perfectly when he says the numbers tell you a lot of stories simultaneously—the trick is figuring out which one really matters.

Neslin’s case in point concerns customers who haven’t bought for a while—one set of data tells you they’re not worth pursuing, while another says they are; which story is right? Susan Fournier of Boston University and Bob Rietveld of analytics firm Oxyme ask a related question: Is big data enough? Aggregate numbers can tell you a lot, but they say very little about how individual customers are thinking and talking about your products.

In a business-to-business context, Joël Le Bon of the University of Houston takes the question further, pointing out an often-overlooked, small-data source of useful information about your competitors’ plans and schemes: Your sales reps. He explains how to cultivate a strong flow of intelligence that can have a powerful impact on strategy.

In other articles, we’ll move beyond specific cases to get at the broader question of how managers can learn to pick the most important kernels of knowledge from the rush of data. Is it critically important for companies’ consumer-data teams to have someone who truly understands statistics in a leadership position, or can an untrained manager learn to be more discerning about data?

And are there times when you should completely ignore the data and go with your gut?

After all, if companies often fail to analyze data in ways that enhance their understanding and neglect to make changes in response to new insights, as Jeanne W. Ross and Anne Quaadgras of MIT and Cynthia M. Beath of the University of Texas say in the current HBR, then what’s the point of paying big money for big data?

While recognizing companies’ struggles to make sense of information, Ross et al argue that what really matters more than the type and quantity of the data is establishing a deep corporate culture of evidence-based decision making. That means establishing one undisputed source of performance data, giving all decision makers feedback in real time (or close to it), updating business rules in response to facts, and providing coaching for decision makers. It also means encouraging everyone in the organization to use data more effectively.

The sentiment about including everyone in the company in the use of data is echoed by McKinsey: When business-unit leaders invest in training for managers as well as end users, “pushing for the constant refinement of analytics tools, and tracking tool usage with new metrics,” companies do eventually transform themselves, bringing data-driven thinking into all aspects of the business and fulfilling data’s vast potential.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

Are You Ready for a Chief Data Officer?

Does Your Company Actually Need Data Visualization?

Nate Silver on Finding a Mentor, Teaching Yourself Statistics, and Not Settling in Your Career

Stop Assuming Your Data Will Bring You Riches

Who Wants to Work for a Woman?

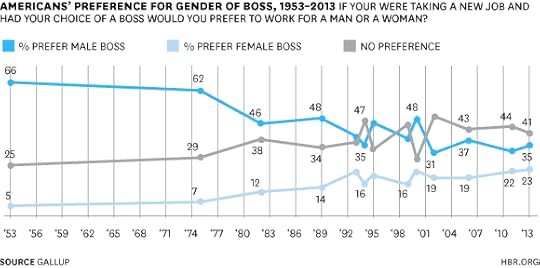

The year my husband was born (1953), only 5% of Americans preferred a female boss. That number has climbed to 23%, according to a new Gallup survey. The proportion of people who prefer to work for men fell precipitously, from two-thirds in 1953 to about one-third today.

Perhaps even more important is the sharp rise in Americans who expressed no preference, even when cued to care. Gallup’s question asked, “If you were taking a new job and had your choice of boss, would you prefer a man or a woman?” Only 25% of Americans expressed no preference in 1953 but today it’s 41%. More good news: more people judge their bosses not by their gender, but as people. This is more likely to be true the higher the level of the job. Only 36% of those with high school or less, but 46% of those postgraduate degrees, expressed no preference.

Male privilege, you might say, ain’t what it used to be.

Once we scratch the surface, though, the news is nastier. Americans who currently work for men are twice as likely to prefer to do so. Only 16% of Republicans prefer a woman boss. American women still face a steep uphill climb, something the pipeline won’t fix: young people (18 to 34) are more likely to want a male boss and less likely to express no preference than Americans aged 35 to 54.

Most striking is that a much higher percentage (40%) of women than men (29%) prefer to work for a man. Women also are more likely than men to prefer to work for a woman: 27% of women versus only 18% of men.

Both these statistics are puzzling, but I may have an explanation for each.

Women might prefer to work with women for two reasons. They might, first, feel this offers them some protection from gender bias, including sexual harassment. Second, women without college degrees typically are in pink-collar jobs that have a distinctly feminine feel a male boss might disrupt.

How about the women who prefer a male boss? Have they just been burned by Devils Wearing Prada?

They may have experienced workplaces where gender bias pits women against other women, a pattern The New Girls’ Network calls the “Tug of War.” An important 2010 study of legal secretaries by law professor Felice Batlan illustrates this dynamic, as does my own research. Batlan surveyed 142 legal secretaries and found that not one preferred to work for a woman partner (although, importantly, 47% expressed no preference).

Why did many secretaries prefer male bosses? Simple: they aren’t dummies. In most law firms, most people who hold power are men. Women stall out about 10 to 20% of the time in upper-level management in professional fields like business and law, so if you’re aiming to hitch your wagon to a shooting star, men are a better bet. This is one way gender bias pits women against women.

Another is when women stereotype other women. “I just feel that men are more flexible and less emotional than women,” one secretary said, while another described women lawyers as “too emotional and demeaning.” The stereotype that women are too emotional goes back hundreds of years.

But “demeaning”? That’s interesting. Her boss may just be a jerk — some people are — but perhaps she was just busy. While a busy man is busy, a busy woman, all too often, is a bitch. Because high-level jobs are seen as masculine, women need to behave in masculine ways in order to be seen as competent. But if they behave too much like men — watch out.

This no-win situation fuels conflict between women who just want to be one of the guys and those who remain loyal to feminine traditions. “Secretaries are expected to engage in traditionally feminine behavior such as care giving and nurtur[ing], where[as] women attorneys are supposed to engage in what is stereotypically more masculine behavior. Given these very different expectations and performances of gender that occur in the same space, the potential for conflict is enormous,” Batlan concludes. Indeed, many professionals find themselves expected to do what Pamela Bettis and Natalie G. Adams, in an unpublished paper, call “nice work”: being attentive and approachable in ways that are often time-consuming and compulsory for women but optional for men.

Conflict also erupts due to Prove-It-Again problems: women managers have to provide more evidence of competence as men in order to be seen as equally competent. This pattern again pits women against their bosses. “It would seem as if female associates/partners feel they have something to prove to everyone,” noted one secretary. “Females are harder on their female assistants, more detail-oriented, and they have to try harder to prove themselves, so they put that on you,” said another.

But it’s not just female assistants who voice concerns about their bosses.

The interviewees for my forthcoming book What Works for Women at Work, co-written with my daughter Rachel Dempsey, illustrate yet another dynamic: some admins make demands on female bosses that they don’t make on men. And like many types of gender bias, this one’s inflected by race. One black scientist I interviewed felt her relationship with white administrative assistants was strained because, she said, she didn’t share their habit of bonding by sharing personal information (what Deborah Tannen called “troubles talk”). Black admins “just do not expect me to want to know anything about their personal business,” she said with some relief.

Women bosses also often feel that admins prioritize men’s work. One scientist I interviewed noted that administrative staff took longer to complete work given by women than men. Another agreed: “My stuff won’t get done first.” “They say the bosses are too demanding,” said a third, recalling a conversation with admins who worked with her. She had responded, “Well, the boss that you had before was equally demanding. The guy that you were working under was equally demanding.” The admins’ reaction: “Yeah, but that’s different.” Again, the secretaries know which side the butter’s on. And the female scientists I interviewed typically felt less powerful than their male counterparts.

As usual, gender dynamics are far from simple. The Gallup study confirms the eternal story: when it comes to gender flux, the glass is half full — employees now are more comfortable with female leaders and are more likely to simply treat people as people, leaving traditional gender stereotypes behind. But the glass is also resounding, maddeningly, persistently half empty. I read the evidence that more women than men prefer to work for women as evidence of persistent gender bias. And I read the evidence that more women than men prefer to work for men the same way.

Trouble with the Curve? Why Microsoft is Ditching Stack Rankings

“No more curve,” said Lisa Brummel, Microsoft’s EVP of HR last week, curtly dismissing Microsoft’s much-derided but iconic practice of ranking each team member on a forced distribution. This was big news, the lead of many a business section. After all, this practice of “stack ranking,” of being forced to rate every single one of your team on a bell curve from excellent to poor (even if the whole team had, in fact, performed excellently) has been singled out by everyone from HBR to Vanity Fair as one of the reasons for Microsoft’s inability to foster high-performing teams, a major cause of its “lost decade.”

And not just big news, but welcome news for anyone who has ever struggled to keep a straight face while telling a direct report that a “3” really isn’t that bad, that it truly does mean “meets expectations,” and that, hey, sixty percent of the company gets that rating, so don’t be too down on yourself.

However, welcome as it is, Microsoft’s ditching of stack ranking isn’t the big news—according to a Corporate Executive Board survey, only 29% of companies use a forced curve in their performance management system. No, the big news came in the next paragraph of Lisa’s email:

“And no more ratings,” she said.

No more ratings? According to the CEB study, more than 90% of all companies surveyed use some kind of rating system to measure performance. Every single one of the big Human Capital Management (HCM) software companies, from Oracle to CornerstoneOnDemand to SuccessFactors, uses ratings as the lynch pin of its platform. These ratings—of overall performance, and of the many competencies that apparently combine to create overall performance—are the raw material for everything else that the company does to and for its people. These ratings feed compensation. They guide succession planning. They pinpoint performance gaps and then trigger the necessary training and learning interventions. These ratings are the lingua franca of performance, and are so central to performance management that HCM software providers are competing with each other to see who can help managers generate them faster, explain them better, and display them ever more graphically. All systems are designed to produce something. For HCM systems, that something is ratings.

So, if Microsoft is ditching ratings, if they are saying that ratings hinder performance rather than help it, what does that mean for the 90% of us who labor every six months to generate them for our teams? And what does it mean for the software providers whose systems compel us to do so?

Hard to say, of course—after all, on the day Microsoft announced its rejection of ratings, Yahoo was publicly struggling with the fall-out from its botched re-launch of stack rankings. Nonetheless, when Microsoft throws out ratings, and on closer scrutiny one discovers that in the last year many other companies, such as Adobe, Medtronics, Kelly Services, NY Life, and Juniper have done the same, it’s time to sit up and pay attention. Performance, how we manage it, measure it, and reward it, is changing. And so now is an excellent time to ask ourselves “What is the world we are leaving behind and where precisely are we headed?’

The world we are leaving behind is unquestionably a deeply unpopular world—not only do most managers dislike their performance management system, but most human resources professionals don’t like theirs, either. One cause of this dissatisfaction is a misunderstanding of motives: managers think that their performance management system is designed to help them accelerate the performance of their people. I would argue that a performance management system should be designed primarily for this purpose, and indeed some purport to be—but scratch the surface and you quickly learn that they aren’t.

Instead the purpose of these systems is twofold: first, to allocate compensation fairly; and second, to align each individual’s goals with the values and strategies of the company. These aren’t nefarious purposes—they are actually rather sensible—but they are clearly secondary or at least tangential to helping employees become more productive.

Companies could probably alleviate some of the current dissatisfaction by being more straightforward that the performance management system is not for you, the employee; it is instead a company system, designed to ensure a bell curve of compensation, and alignment to company goals. Not a particularly uplifting positioning, I grant you, but at least employees and managers would be able to judge it on its own terms.

Of course, this wouldn’t fix the underlying problem of ratings – which is that, for a variety of reasons, they turn out to be bogus (a topic I will address in a follow-up post). Perhaps most managers have long suspected this. Perhaps their dissatisfaction with performance management systems stems from this suspicion. Either way, Microsoft’s rejection of ratings has done all of us a service. It shines a harsh spotlight on the approach that defines performance management today, and helps others see that it is seriously overrated.

A New Model for Innovation in Big Companies

It seems we’re all racing to get more entrepreneurial. Increasing creativity and innovation is not only on the priority list for start-ups; it’s also a strategic goal for CEOs of small, medium, and large-sized companies. Despite this growing obsession, however, big companies are still not very good at it. How many times have you had a strategy meeting that gathered a smart, enthusiastic team to generate interesting ideas and debate their merits, yet after the meeting… nothing… much… happened?

Studies show that efforts to stimulate intrapreneurship — entrepreneurship within an established company — more often than not fall flat. According to my current research at Harvard on innovation models in global companies across diverse sectors, these types of projects fail between 70% and 90% of the time.This should be a deeply troubling, motivating statistic. And it’s one that stems from a very human problem in most big organizations.

“There are lots of things that can be done in large organizations but simply aren’t because nobody has the time or resources.” Call it a grim view, but this quote from my research summarizes a pattern I see frequently. This participant — the CEO of the India and South Asia division of a global firm — continues: “To actually get something going in a large organization, you need the ideas and you need the people who believe in them, but the people who are actually capable of these things are the good ones, and they are already stretched by their work in the corporate environment…. It [becomes] impossible for them to pull it off.”

As companies grapple with long odds on innovation like these, they are also looking for ways to improve the likelihood of their intrapreneurial success. Internal innovation presents a number of challenges, including but not limited to the inherent risk of promoting new ideas; complacency and attachment to the status quo; and the actual amount of capable people with the time to effectively build new ideas into workable products.

Traditionally, companies have found ways to navigate these challenges internally, in research and development (R&D) divisions like the famed Xerox PARC, founded in 1970, or through programs that encourage employees to dedicate a small percentage of their time to side projects, as 3M began doing in 1948. Many companies, including Google, follow similar models today.

Since the 1990’s, however, more and more large companies have been outsourcing their intrapreneurial efforts. They pay upwards of $300K to $1 million to consultancy firms that conduct market analyses and in-depth need-finding, identify new opportunities, generate promising ideas, and, often, develop ideas into working prototypes. The client company then refines these concepts and prototypes and takes them to market. Innovation consultancies tend to have a preferred methodology for working with their clients, such as human centered design (also called ‘design thinking,’ popularized by IDEO, Continuum, Frog Design and others), Lean Start-up, or analytical models used by large management consulting firms. Results from these business-to-business collaborations have at times been phenomenally successful, as was the case with the Bank of America Keep the Change program (IDEO) and the Swiffer (Continuum Innovation).

Undoubtedly, not all inventions from these collaborations achieve equivalent fame, or we likely would have heard about them. It is difficult to say whether the success rate of clients working with innovation consultancies is radically above the 10-30% success rates for intrapraneurship projects, but there is some indication in my research that design firms indeed provide their large company clients with ideas promising enough to improve on these odds. In addition, an often-underappreciated factor influencing how successful the design team to client handoff will go is whether the client is set up organizationally to deliver the product. And this brings us back to the question of whether the people required to do this internally have the time and resources to pull it off.

All of this can make clients, who are paying high fees for innovation consulting, nervous. And it seems to be opening the door for new options that emphasize a deeply pragmatic approach to innovation, including mixing entrepreneurs and corporations.

A Different Approach

Remo Masala, Chief Marketing Officer at Kuoni, is one of the executives taking his company in a new direction. Masala has been at Kuoni, a leading travel services company, since 2007, and is known for frequently shaking things up. He even sees this as a fundamental part of his job: “You need to understand as a company, to be different means also to start to act differently.”

So nobody was shocked when, for a recent strategy project, Masala passed over many well-known consultancies that he viewed as having already “made a science out of their way of thinking of restructuring.” He was looking for an outside team to help Kuoni approach this question, but there were a few ground rules. He wanted them to be open to multiple methods. He was especially sensitive to the human side of how this would get approved and implemented internally. Masala also wanted everything to happen quickly — for the teams to work within very tight time and budget constraints, produce fast results, quantitatively analyze them, and to help Kuoni make the decisions required to take the ideas forward.

That’s when Masala met Hamish Forsyth, Co-Founder of OneLeap, a UK-based innovation consultancy with a rather unusual background. OneLeap began a platform enabling aspiring entrepreneurs from around the world to contact high profile investors, corporate leaders, and partners to help grow their start-ups. As they built up a unique network of thousands of entrepreneurs across 35 countries, they started to see that there was a lot of demand in reverse — companies kept asking them for advice on how to become more entrepreneurial instead of wanting to simply connect with entrepreneurs. This led the organization to start experimenting with ways that companies could learn directly from their network of entrepreneurs.

Instead of bringing teams of multi-disciplinary designers into large companies as other consultancies have been doing, OneLeap began bringing in teams of diversely skilled entrepreneurs. On the surface, this may sound similar to other innovation consultancies. But beyond the surface, there are several core differences.

OneLeap’s entrepreneurs remind big companies of their riches, and to take nothing for granted. Large companies often think they’re strapped for resources, but entrepreneurs can’t believe how many resources they have. For example, Dorjee Sun, one of the entrepreneurs brought in to Kuoni, has been starting companies since he was 19. This Singapore-based entrepreneur has had multiple exits in tech and education, and was recognized in 2009 by Time as a ‘Hero of the environment’ for his work in the Carbon Conservation business. While working on the project, Sun kept emphasizing possibilities: “If I had 2 million people coming through my 500 stores, and I had this many thousand people working for me, and I had a 160 year history, of course I would do that. If Instagram and AirBnB and Kayak and Hipmunk can start with zero, just think what they would have done if they had had your distribution pipe!” Entrepreneurs, says Sun, can help remind companies to value what they might take for granted by asking, “Why don’t you do this? How can you not [do this]?!”

Entrepreneurs help large companies to combine relentless focus, expansive search and a bootstrapping mentality. In a start-up, if entrepreneurs don’t focus relentlessly on the core of their idea, the results can be devastating. Related to this radically resourceful view, research shows that, compared to more established, well-resourced companies, entrepreneurs and companies with entrepreneurial management practices are innovative in part because of their resource constraints. Constraints encourage them to focus on their existing advantages and remain experimental. Instead of investing primarily in maintaining the familiar, as those with excess resources tend to do, they invest heavily in active search for unmet needs, creative ways to recombine knowledge or resources, and new opportunities to apply their competitive advantages.

OneLeap thus starts the process of working with large firms with a systematic analysis of the company’s advantages conducted by a group of diversely skilled entrepreneurs. This can provide a useful contrast to blue sky innovation sessions, where ‘no ideas are bad ideas’ and many ideas are so outside of a company’s core competencies that they aren’t remotely actionable.

Entrepreneurs can help big companies try on a bootstrapping mentality, where there is no time or budget to lose focus. This may seem counterintuitive in a larger organization. After all, big companies have the luxury of experimenting broadly, right? While that may be true in terms of financial luxury, this perception can also be misleading. It can take the perceived pressure off, while underestimating the fact that it takes dedicated time and human resources to build a promising idea into a viable product, and those resources are often already accounted for on other projects.

Tailored short-term teams with radically diverse yet relevant skills help identify opportunity areas quickly. OneLeap does not employ entrepreneurs; they employ facilitators, and are essentially a network of, and platform for, entrepreneurs to engage with large companies. This means their entrepreneurial teams are not coming from the same consultancy. Rather, they are one-time teams of proven entrepreneurs, hand-picked from an active network of thousands of them, and brought together on a case-by-case basis for each client project. This means the client can specify the skills they need, and OneLeap can compose a group that has them.

Once this team is confirmed, OneLeap works with their client to set up a semi-autonomous unit of entrepreneurs inside the large company for about six weeks. OneLeap structures and manages the engagement between the entrepreneurs and client internal management according to research on key differences between start-up and established company approaches to innovation.

OneLeap’s partnership with Kuoni began with selecting the right entrepreneurs for the project. They were selected based on the following criteria: experience, recognition (objective awards, financial exits, other recognition), peer referencing, geographic representation (entrepreneurs had experience living and operating in markets of interest to Kuoni), sector expertise and variety (some expertise in travel, but also in sectors from which recombinant innovation was possible — e.g. food, retail services etc), and functional variety, with strong digital representation (entrepreneurs are naturally multi-functional, but may have specific areas of domain expertise). On this project, an exploration of B2C opportunities in a market beset with digital new entrants, digital was important. However, OneLeap always tries to include a good digital representation because digital entrepreneurs are comfortable with seeing how a product can be quickly prototyped.

Facilitated internal hackathons help companies get past slow decision-making and embrace competition. The entrepreneurial teams work with the client teams to build real prototypes on-site. And they don’t leave until it is done. One of the entrepreneurs, Sun, describes it as: “a workshop… turned into a hackathon. By having these internal hackathons, it is like replicating a Facebook culture, where basically Timeline was developed in 24 hours as people just went about it.” In essence, OneLeap runs something like an accelerated competition and incubator inside the company. OneLeap and the entrepreneurs help the company select the top ideas for prototyping.

OneLeap helps companies test prototypes quickly with real customers to get the right data to decide whether to keep or kill ideas. The prototypes then move through an intensive analysis phase. OneLeap has built ways to test prototypes first within the company and then with real consumers, and analyze the results with the objective of preparing the company to make an informed decision on what to take forward, how to get buy-in and out how to scale it. The prototyping and analysis process is highly data-driven and can wrap up in as few as six weeks. To do this, OneLeap built a simple white-label prototype and tested it with several thousand of Kuoni’s existing customers. The prototype was very light, but explained the concept using a mockup of the fully functional product, and tested varying levels of commitment through signups, a basic diagnostic, and social shares. While not yet proof that the product would succeed, it gave Kuoni the data it needed to discuss the concept and engage the board. And subsequent access to OneLeap’s resources can help maintain momentum.

Several months after the program, I interviewed Masala again, this time to ask about his return on investment. He articulated two lasting benefits: organizational and product-related. First, he said, you “have to fix the basics.” His experience with OneLeap provided assurance that what they were trying to do made sense, and they have since begun to structure themselves differently. The organizational return was a shift to a more entrepreneurial and experimental mindset in the daily business. The experience “left a good feeling in the company, we were very, very satisfied, and OneLeap will be back with us.”

Beyond the organizational returns, Masala is thinking long term. “We were lucky to have many ideas, but if Kuoni starts a business from one of the ideas that emerged from working with OneLeap’s entrepreneurs, judging the ROI is different.” He compared it to assessing ROI with any method: if you build an idea out to delivery, you still have to find the right people and you still have to deal with risk. When determining his returns so far from working with OneLeap, he “would have to compare this cost-wise to building it out on a green meadow.” In the end, he assumed the cost would be similar. But for him, the key question is: in which version are you more successful? “In the end it is about the people doing it.” That is, Kuoni and Masala are serious about allocating resources — people, time and funding — so that ideas developed in the workshop have a fighting chance to succeed.

Although companies seldom address it head on, between idea and implementation often lurks the ‘I will if you will’ attitude that avoids a real discussion of time and resource investment into the innovation pipeline and breeds diffusion of responsibility and complacency. This tricky mentality is enough to suck the air out of even the most promising ideas. OneLeap and Kuoni present a provocative case for a new form of organizational collaboration that uses entrepreneurs to stimulate and sustain innovation in large companies.

Instead of the typical meeting to generate and debate ideas that then languish thereafter due to lack of sufficient investment and time and resources, your next innovation project could have one key difference: a forceful group of successful entrepreneurs from selected fields participating in the sessions. They’re not only contributing ideas and mocking them up, but also — importantly — they are asking tough questions that just might help big companies kill the dreaded ‘I will if you will’ dynamics that can stymie the development of promising ideas.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers

![paidmore2[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385023222i/7048026.png)

![longerhours2[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385023222i/7048027._SX540_.png)