Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1508

November 26, 2013

Be Grateful More Often

Although I didn’t move to the United States until I was an adult, every year I look forward to one of the most American of holidays: Thanksgiving. Turkey, pumpkin pie, long hours of cooking and relaxing with family and friends make the day a particularly fun one. I also look forward to Thanksgiving for another important reason: it is a day that reminds us of the importance of expressing gratitude.

Even though many of us have numerous occasions to feel grateful in both our personal and professional lives, we often miss out on opportunities to express gratitude, especially at work. A recent survey of 2,000 Americans released earlier this year by the John Templeton Foundation found that people are less likely to feel or express gratitude at work than anyplace else. We are not even thankful for our jobs, which tend to rank dead last when asked to list the things we’re grateful for in our lives.

Failing to express gratitude when we can is a missed opportunity for at least two reasons. First, feeling grateful has several beneficial effects on us: gratitude enables us to savor positive experiences, cope with stressful circumstances and be resilient in the face of challenges, and strengthen our social relationships. Psychological research [PDF] has shown that writing letters of gratitude once a week over a six-week period leads to greater life satisfaction as compared to simply recording ordinary life events.

Counting our blessings doesn’t just cheer us up; it can also improve our health and well being. In a series of well-known studies [PDF], psychologists Robert Emmons and Michael McCollough asked participants to keep weekly journals for ten weeks. Some were asked to write about five things or people they were grateful for each week, some were asked to write about five hassles that they experienced during the week, and a third group was asked to write about any five events that occurred during the week. Participants asked to list hassles included the following: hard-to-find parking, spending their money too quickly, and burned macaroni and cheese. Those who listed blessings mentioned experiences such as the generosity of their friends, learning something interesting, and seeing the sunset through the clouds. Those in this gratitude group scored higher on measures of positive emotions, self-reported symptoms of their physical and mental health, and they also felt more connected to others as compared to those who made routine notes about their days or wrote about hassles.

A second reason to pause to express gratitude is that even simple expressions of gratitude can have powerful and long-lasting effects on those who receive them. In our research [PDF], Adam Grant and I found that expressions of gratitude increase prosocial behavior by enabling people to feel socially valued. In one study, participants edited a student’s cover letter and then received either a neutral message from the student (i.e., “Dear [name], I just wanted to let you know that I received your feedback on my cover letter”) or a grateful one (“Dear [name], I just wanted to let you know that I received your feedback on my cover letter. Thank you so much! I am really grateful”). The student sending the message subsequently asked for help on another cover letter—well after the experiment had ended and participants had no obvious incentives to help. Among those who were thanked, 66% were willing to provide further assistance, as compared to just 32% of those who had not been thanked.

In a second study, we found that participants who helped a first student (“Eric”) and then were thanked were more likely to help a different student (“Steven”) later on. Only 25% of participants who helped Eric and received a neutral note decided to help Steven; by contrast, 55% of those who helped Eric and received a thank-you note from him decided to help Steven. Thus, receiving expressions of gratitude made people feel socially valued and motivated them to help other beneficiaries.

These simple expressions of gratitude are quite powerful in the context of helping, but their effects are even broader. In one experiment, we divided 41 fundraisers at a public U.S. university who were soliciting alumni donations into two groups: the “thanked” and the “unthanked.” The thanked received a visit from the director of annual giving, who told them: “I am very grateful for your hard work. We sincerely appreciate your contributions to the university.” The other group received daily feedback on their effectiveness, but no expressions of gratitude from their director. The result? The weekly call volume of fundraisers in the thanked group increased by 50% on average the week after the intervention took place, all because the director’s expression of gratitude strengthened the fundraisers’ feelings of social worth.

Thanksgiving is a great time to think about gratitude, but a dive into the research around giving thanks makes it clear that we should be doing more of it throughout the year.

November 25, 2013

Why Walmart’s Senior Execs Need to Be on Twitter

It’s been a rough month in the media for Walmart.

Last week, Walmart found itself in a Twitter tussle with actor Ashton Kutcher over the company’s controversial low wages. Pictures of food drive collection bins — to benefit Walmart employees — in one of its stores went viral. Kutcher tweeted at the company, saying “Walmart is your profit margin so important you can’t Pay Your Employees enough to be above the poverty line?” with a link to a post on The Wire about the employee food drive. The Walmart PR account tweeted back, saying, “It’s unfortunate that an act of human kindness has been taken so out of context. We’re proud of our associates in Canton.” Throughout the back-and-forth, Walmart came off as defensive and tweeted facts that some have recognized as a bit murky: “We think you’re missing a few things. The majority of our workforce is full-time and makes more than $25,000/year.” About an hour after the exchange, Kutcher tweeted, “Walmart should be the leaders not the low water mark” along with a link to an article about UC Berkeley’s Institute for Industrial Relations study, “The Hidden Cost of Wal-Mart Jobs”, detailing how low wages for California’s Walmart employees cost state taxpayers $86 million each year in healthcare and welfare programs like SNAP.

This exchange comes amid growing chatter about Walmart’s low wages and other controversial practices. On Monday the National Labor Relations Board had announced it “would prosecute the retailer for illegally firing or disciplining 117 striking workers… many [stemming] from last year’s Black Friday protests,” according to Forbes. Another round of strikes have been organized for this year’s Black Friday, at the end of this week. Walmart has also been firing back against criticism about the store starting Black Friday earlier on Thanksgiving Day, and their CEO has just announced he’ll step down in the wake of a bribery scandal. Oof. (Disclosure: WalMart was my client when my team advised them to launch the company’s first blog in 2005, chronicling Walmart’s recovery efforts post-Hurricane Katrina.)

Fortune 500 companies want to use social media to be more transparent, responsive and authentic. They want to show customers and shareholders what’s great about their brands. That’s why most have invested in robust social media programs, and responsive Twitter accounts. But the same flow of conversation, images, and ideas that make social media such a powerful storytelling tool also make it extremely dangerous for brand and reputation management. I see two main problems that contribute to this: 1) that social media managers don’t spend more time preparing for negative coverage, and 2) that social media conversations aren’t being heard by the people with decision-making authority.

Frontline communicators in the communications or digital marketing department sign up to manage these sudden social media fires, but not all of these conflagrations are created equal. Some are helpful (generating heat and light) while others are negative (difficult to control and potentially very destructive). Today, many public relations departments actively want to “light brush fires” — the positive kind — on social media. They want to connect with various influential people or networks online and allow them to cascade a news story into the public consciousness (think of viral ads like Dove’s Real Beauty sketches or any of the marketing around Google’s Project Glass). But the problem with fire is that once one ignites, it’s difficult to control. And despite their interest in lighting positive brush fires, too many firms are caught off-guard when the flame turns destructive.

Too many digital marketers spend far too much time trying to come up with clever digital gimmicks they hope will go viral and not enough time laying down the communications basics to respond to negative feedback. Cute marketing cannot sugarcoat bad products or, in Walmart’s case, labor practices.

Communications departments have often been left to explain flawed policies or products to the public — that is nothing new. But it is more challenging to do so instantaneously, authentically, and in 140 characters in a forum where the public can also respond immediately. It’s always difficult to make the call as a communicator in the moment. The impulse is to quickly extinguish a negative fire before it spreads, but that can often exacerbate the problem. Would it have been better to wait a bit and formulate a more measured response to Kutcher’s first question about the company’s profit margin? The days are gone when we had hours to put out a statement; Walmart took 14 minutes to fire back. Speed, today, is table stakes.

And so the key is not immediacy, but seniority. Think how differently this might have unfolded if a senior executive actually responsible for labor practices had read and responded to Kutcher’s comment — and all of the other tweets that stemmed from the exchange. Yes, that’s extremely unlikely to happen — and JPMorgan Chase’s recent unfortunate experience with a Twitter chat ensures even fewer executives will take to social media on behalf of their firms.

Instead, we are left with half-truths driving the corporate use of social media. Nominally employed to foster transparency, frontline communicators are actually there all too often to form a barrier between the public and corporate executives. Consumers don’t know if our social media feedback gets any higher than the online newsroom, and no one on either side ever really feels satisfied with corporate responses.

So even if today’s digital teams could prepare for every possible negative brush fire waiting to flare, social media’s real potential won’t be realized until the senior executives in charge of product and policy are part of the conversation. Ultimately, social media is about give and take, questions and answers. Companies that only participate in the half of that exchange — or limit their participation to the PR department — are truly playing with fire.

Reduce Your Stress in Two Minutes a Day

Bill Rielly had it all: a degree from West Point, an executive position at Microsoft, strong faith, a great family life, and plenty of money. He even got along well with his in-laws! So why did he have so much stress and anxiety that he could barely sleep at night? I have worked with Bill for several years now and we both believe his experience could be useful for other capable, driven individuals.

At one time, no level of success seemed enough for Bill. He learned at West Point that the way to solve problems was to persevere through any pain. But this approach didn’t seem to work with reducing his stress. When he finished his second marathon a few minutes slower than his goal, he felt he had failed. So to make things “right” he ran another marathon just five weeks later. His body rejected this idea, and he finished an hour slower than before. Finally, his wife convinced him to figure out what was really driving his stress. He spent the next several years searching for ways to find more joy in the journey. In the process he found five tools. Each was ordinary enough, but together they proved life-changing and enabled his later success as an Apple executive.

Breathing. He started small by taking three deep breaths each time he sat down at his desk. He found it helped him relax. After three breaths became a habit, he expanded to a few minutes a day. He found he was more patient, calmer, more in the moment. Now he does 30 minutes a day. It restores his perspective while enabling him to take a fresh look at a question or problem and come up with new solutions. Deep breathing exercises have been part of yoga practices for thousands of years, but recent research done at Harvard’s Massachusetts General Hospital document the positive impact deep breathing has on your body’s ability to deal with stress.

Meditating. When Bill first heard about meditation, he figured it was for hippies. But he was surprised to find meditators he recognized: Steve Jobs, Oprah Winfrey, Marc Benioff, and Russell Simmons among them. Encouraged, he started with a minute a day. His meditation consisted of “body scanning” which involved focusing his mind and energy on each section of the body from head to toe. Recent research at Harvard has shown meditating for as little as 8 weeks can actually increase the grey matter in the parts of the brain responsible for emotional regulation and learning. In other words, the meditators had increased their emotional control and brain power!

Listening. Bill found if he concentrated on listening to other people the way he focused when he meditated his interaction immediately became richer. The other person could feel he was listening, almost physically. And when they knew he was listening they formed a bond with him faster. Life almost immediately felt richer and more meaningful. As professor Graham Bodie has empirically noted, listening is the quintessential positive interpersonal communication behavior.

Questioning. This tool isn’t about asking other people questions, it’s about questioning the thoughts your mind creates. Just because your mind creates a thought doesn’t make it true. Bill got in the habit of asking himself “Is that thought true?” And if he wasn’t absolutely certain it was, he just let it go. He said: “Thank your mind for coming up with the thought and move on. I found this liberating because it gave me an outlet for negative thoughts, a relief valve I didn’t have before.” The technique of questioning your thoughts has been popularized by Byron Katie who advocates what she calls “the great undoing.” Her experience and research show there is power in acknowledging rather than repressing negative thoughts. Instead of trying to ignore something we believe to be true, questioning allows us to see our thoughts “face to face” and to discredit them because they are untrue.

Purpose. Bill committed to living with purpose. Not so much a Life’s Purpose — it was easier than that. He committed to purposefully doing whatever he was doing. To be doing it and only it. If he decided to watch TV he really watched it. If he was having a meal he took the time to enjoy the meal. There is research to support Bill’s experience. In “A Pace Not Dictated by Electrons: An Empirical Study of Work Without Email” Gloria Mark and Armand Cardello cite evidence to suggest knowledge workers check email as much as 36 times an hour. The result is increased stress. Giving each activity your undivided attention ensures you’re in the moment and fully living that experience.

An important key for Bill in all of this was starting small—very small. It’s important because you can’t take on stress in a stressful way. Often we try to bring about change through sheer effort and we put all of our energy into a new initiative. But you can’t beat stress using the same techniques that created the stress in the first place.

Instead, the key is to do less than you feel you want to. If you feel like breathing for two minutes, do it for just one minute. If you are up for a day of really listening to people deeply, do it for the next meeting only. Leave yourself eager to try it again. What you want is to develop a sustainable habit: a stress-free approach to reducing your stress.

How CMOs Can Get CFOs on Their Side

Marketing is in the midst of an ROI revolution. The arrival of advanced analytics and plentiful data have allowed marketers to demonstrate return on investment with a degree of precision that’s never been possible before. The opportunity is enormous. In our experience, companies that adopt this marketing analytics approach can unlock 10–20 percent of their marketing budget to either reinvest in marketing or return to the bottom line.

To date, however, the reality of marketing analytics has fallen short of the promise. Just 36 percent of CMOs, for example, have quantitatively proven the short-term impact of marketing spend, according to the 2013 CMO Survey (and for demonstrating long-term impact, that figure drops to 32 percent). That means that almost two out of three CMOs are using qualitative measures to show impact, or aren’t measuring impact at all. Moreover, the previous year’s survey showed that 63 percent of projects do not use analytics to inform marketing decisions.

This lack of an analytical approach has traditionally formed a barrier between marketing and finance. One financial services CMO told us how CFOs typically perceive his function: “We’re going to give a certain amount of dollars to those guys. They’re going to make ads and do whatever it is they do. And let’s hope it generates demand.’”

To reverse this perception and to get greater bang for marketing’s buck, we believe that CMOs must become true collaborators with CFOs and adopt a marketing ROI approach that’s driven by analytics.

It doesn’t need to be complicated; in one company, a marketing department saved 20 percent after simply benchmarking the money they were spending on external agencies. And at another — a consumer packaged goods company — a series of strong brands had evolved in separate silos. Only when they began to really analyze their marketing costs did the company realize that it was spending three times the industry benchmark on coupons and 50 percent more on research. It was also using more than 50 different market research companies to conduct similar tasks.

Without a strong business case built on analytics, marketing too often is seen as a cost rather than an investment, despite marketing’s ability to drive above-market growth.

In our work with clients across dozens of sectors over more than five years, we have found that the strongest CMO/CFO partnerships develop when both parties undertake five actions:

1. Use consistent language across departments – and within them.

CMOs need to start building this relationship by having a clear understanding of what CFOs expect. CMOs do have plenty of data, of course, but it’s often not the data that the CFO is looking for. For instance, CMOs often focus on brand awareness, TV ad impressions, or share of voice in the market, which do not easily translate into financial impact. CFOs are more interested in capital investment estimates, net present values, and a clear outline of the trade-offs of any investment.

But it’s no good speaking the same language as the CFO if marketing itself is a Tower of Babel. CMOs have typically found it hard to say what the actual marketing spend is (by product, by market, by strategic intent), how much is spent on customer-facing (creative) initiatives and how much is spent on enabling (IT); how much is focused on different parts of the consumer decision journey; what is the spend on digital and social media (and what is it worth); and how much is spent on non-advertising activities (sponsorship, promotions, trade events).

Why is this so challenging? One reason is that different regions often allocate the same spend to different categories. For example, trade fair expenditure might fall into short-term spend in one market, but the long-term brand-building budget in another. The difference may seem trivial, but they will give the CMO a headache when answering basic questions about where and how marketing dollars are spent. Adding to the complexity is marketing’s increasing need to integrate with other functions in the organization to discover relevant insights from data, design products and offers, and then deliver them to the marketplace.

Creating transparency into its operations is the starting point for marketing to help CFOs understand where and how value is being gained or lost, which makes budgeting discussions much more productive. Bringing everyone into line is essential, but not necessarily easy or quick.

2. Focus on the metrics that matter.

Shareholders don’t care about fans or followers unless those numbers can be tied to profit. CMOs must demonstrate and track marketing’s impact by focusing on key performance indicators (KPIs) that are important for shareholder value such as strong cash flow, cost of capital, return on capital, and operating margin. Marketing KPIs that don’t directly address shareholder value and the company’s objectives don’t tell the CMO or the CFO where marketing efforts are having the most impact.

Together with the CFO, the CMO must develop a set of objectives that directly deliver on financial objectives and business goals. Marketing KPIs need to incorporate customer acquisition and retention targets and costs. It’s the CMO’s job to make sure that metrics reflecting the health and value of the customer base –net present value, lifetime value, return on loyalty, cost per acquisition – get on the balance sheet.

For instance, at one automotive company, the CMO and CFO worked together with their teams to draw up a global set of financial and non-financial metrics for the short and long term. Financial metrics would typically include obvious numbers such as sales, return on investment, and cost per customer. Non-financial metrics included the numbers of people visiting dealers, or long-term indicators of the health of the brand such as number of customers considering the brand.

We’ve often found it helpful to create a chart that cascades out from business and financial goals at the top, to marketing KPIs that align to each of these goals, to tactics and strategies that can deliver on those KPIs, and finally to those metrics that measure the effectiveness of those strategies or tactics.

Although the metrics matter, what matters more is that the CMO and CFO agree on them. They should also agree and commit to regular meetings to assess progress on these KPIs. These meetings should review activities and results using simple charts and graphs that use the same vocabulary and methods used to measure financial goals.

3. Help CFOs focus on the long term.

CFOs often feel like they are under pressure to focus only on short term metrics when in fact value creation for shareholder is driven by generating superior growth and return on invested capital over the long term. As a long-term asset of significant value, the brand should be part of those calculations. Over the past decade, for example, the total return to shareholders of companies with strong brands has consistently been 31 percent higher than benchmarks such as the MSCI World index.

Too often, the brand is perceived as a “fuzzy” asset that’s hard to quantify. CMOs need to redress that misperception and help CFOs understand how critical the brand is to financial impact by providing estimates of brand worth and investment proposals that build the brand based on hard data. CMOs can use advanced analytics and judgment to manage the trade-off between short-term spending to boost sales and longer-term brand building to support the health of the company.

Long-term brand performance is affected by many factors, so determining the spend/impact relationship is challenging. However, calculations that separate short-term effects from long-term benefits can isolate those marketing activities that truly build brand equity.

To give an example, a consumer food brand developed an advertising program combining digital and social media initiatives that ended up delivering sales results similar to traditional marketing at a fraction of the cost. The brand therefore considered massive marketing budget cuts to TV and print advertising in favor of more spend on social media channels. However, when they included long-term effects in their calculations, they realized that digital marketing would deliver only half what they expected. Online displays and social media advertising couldn’t deliver the emotional connection needed to build brand equity that TV advertising could.

4. Get more for the money

CFOs don’t look just at the ROI of the creative process; they want to know the money is being spent wisely. Marketing could certainly take a long hard look at its procurement. In our experience, marketing can shave a significant 5 – 10 percent off of the budget.

Something as simple as benchmarking marketing’s spend on external agencies and developing a deeper understanding of an agency’s true cost to serve the client can reveal astonishing cost saving potential, up to 20 percent in one case.

At a consumer packaged goods company, a series of strong brands had evolved in separate silos, which meant total marketing spend was very inefficient. By analyzing its costs more closely, the company came to understand that it was spending three times the industry benchmark on coupons and spending 50 percent more than the industry average on research and over-testing TV commercials without improving them. It was also using more than 50 market research companies to conduct similar tasks.

5. Ask for the CFO’s help.

As obvious as it may seem, CMOs should invite finance to participate in marketing’s planning process to build bridges and to benefit from financial expertise.

The experience at one global insurance company is illustrative. The company’s CMO found himself under pressure from the board to demonstrate the value of marketing activities—while at the same time, the company’s competitors were massively outspending it. With his budget at risk, he recognized that he needed to quantify marketing’s financial impact.

To build support for his effort, the CMO invited the CFO among other leaders in the business to help him adopt a more investment-oriented approach to marketing. After frequent meetings, they agreed on three goals: to better clarify the role of marketing to the business; to provide coordinated input on requirements and assumptions to better inform the analytics; and to tie the resulting analysis to financial impact. The CFO appointed a representative from finance to join the effort—and the CMO agreed, up front, to discontinue any activities that proved uneconomic.

In the end, the CMO was able to demonstrate quantitatively the impact of marketing on business goals and save his budget. Moreover, in the process, he had developed an analytical approach to show where his next marketing dollar should go and what he could expect in return. This allowed for the CMO to follow an investment-oriented approach to marketing decisions and provided the Finance department with confidence that marketing was investing wisely.

* * *

An analytical approach to marketing doesn’t mean an end to the creativity required to touch people’s emotions. It only means using data to better define when and where marketers should target audiences with which messages—and to demonstrate the value in doing so.

This may not mean an end to difficult CMO-CFO conversations. But we believe it will mean the beginning of a powerful alliance based on trust and a shared understanding of marketing’s role in driving real business value.

Imagine a Future Where Africa Leapfrogs Developed Economies

Dreaming about the future creates dissonance. On one hand, we like to imagine a future utopia: the world is at peace, the moon is colonized, cats and dogs get along, and we all travel to work via hover cars or teleportation. On the other hand, we are disheartened by more realistic thoughts in which the world of the future is pretty much as it is now, just with cooler gadgets and a faster Internet. But what if there were changes taking place, visible changes today that we all see and comment on, which, together, carry enough momentum to utterly change the way we do business 25 years from now?

In 2012, the Industrial Research Institute (IRI) commissioned a foresight study into the future of R&D management called IRI2038. After gathering “signals” about a variety of future and emerging trends, the project leadership generated several plausible scenarios about the future of R&D worth exploring further. In one scenario, Africa leapfrogs the developed world to become a manufacturing and economic powerhouse. Given where we are today, how will this come to pass?

For starters, we have to consider the impact that current sustainability and environmental protection sentiments have on our collective identity. In this scenario, such post-modern values gradually result in ever-stifling regulations to limit how much a company can affect the natural world, eventually granting equal rights to Mother Nature. Seem far-fetched? Ecuador and Bolivia passed such laws in 2008 and 2010, respectively.

As natural resources become further constrained, R&D innovations focus more and more on process and efficiency as the world moves deeper into a zero-sum competition over materials. This gives impetus to a movement already gaining strength: 3-D printing. By streamlining the use of raw materials, and re-using materials from old goods, a zero-waste society emerges.

Cradle-to-grave responsibility over raw materials from company products becomes an asset instead of a burden, and expected legislation shifts material ownership from cradle-to-grave to cradle-to-cradle. This change then produces a flexible, decentralized, 3-D printing black market where goods are capable of being produced quickly, outside the control of large companies, and using resources near at hand. Additionally, the growth of a hyper-competitive churn for new products, which is already taking hold in today’s markets, pushes many companies out of public status — and its requirement to report on all activities and maintain standards dictated by investors. They opt instead to rely on this flexible manufacturing network and be privately held.

Suddenly the world of manufacturing and big business is gradually undermined as free agency gains prominence, natural resources become difficult to obtain and expensive, and consumers expect a faster churn of new products. Africa, with its plethora of lush farmland, petroleum reservoirs, and large mineral deposits, becomes ripe for rapid growth in such a world where the 3-D printing black market feels right at home.

Recognizing the value of their natural resources and with a young, well-educated population (thanks to the rise of online courses), African nations start a process of resource nationalization. Chinese and American interests are suddenly locked out of their previous ability to exploit Africa for its raw materials and African countries unite to develop a “resource empire” under a “Greater Federal Africa,” using a single currency. Unsaddled by legacy power grids and factories, Africa then leapfrogs the rest of the world in the development of a new economy and leads the 21st century in growth and innovation.

We try to anticipate how changes in manufacturing, labor organization, environmental regulations, IP law, product development, and consumer behavior might affect the way we work, but we can never be certain. If one were to say to you today that they expect Africa to rise, unite, and then dominate the global economy sometime in the next three decades, would you believe them? Take a walk through our scenario reports and then ask yourself that question again. Many of the trends that are just emerging today carry with them small kernels of change. Taken together, they represent a complete transformation.

Are you ready for a not-so-far-fetched future led by Africa?

The Pace of Technology Adoption is Speeding Up

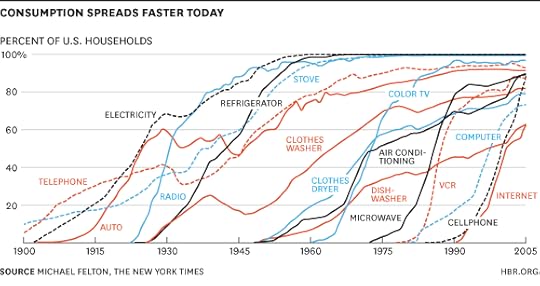

Many people suggest that rates of new product introduction and adoption are speeding up, but is it really, across the board? The answer seems to be yes. An automobile industry trade consultant, for instance, observes that “Today, a typical automotive design cycle is approximately 24 to 36 months, which is much faster than the 60-month life cycle from five years ago.” The chart below, created by Nicholas Felton of the New York Times, shows how long it took various categories of product, from electricity to the Internet, to achieve different penetration levels in US households. It took decades for the telephone to reach 50% of households, beginning before 1900. It took five years or less for cellphones to accomplish the same penetration in 1990. As you can see from the chart, innovations introduced more recently are being adopted more quickly. By analogy, firms with competitive advantages in those areas will need to move faster to capture those opportunities that present themselves.

This second graph, by Michael DeGusta of MIT’s Technology Review, presents similar results. It took 30 years for electricity and 25 years for telephones to reach 10% adoption but less than five years for tablet devices to achieve the 10% rate. It took an additional 39 years for telephones to reach 40% penetration and another 15 before they became ubiquitous. Smart phones, on the other hand, accomplished a 40% penetration rate in just 10 years, if we time the first smart phone’s introduction from the 2002 shipment of the first BlackBerry that could make phone calls and the first Palm-OS-powered Treo model.

It’s clear that in many arenas things are indeed speeding up, with more players and fewer barriers to entry.

How is Big Data Transforming Your 80/20 Analytics?

Even today, most organizations technically struggle to answer even the simplest 80/20 analytics questions: Which 20% of customers generate 80% of the profits? Which 20% of suppliers are responsible for 80% of customer UX complaints? What 20% of customers facilitate 80% of the most helpful referrals? Indeed, even organizations where top management keeps their eyes glued to KPI-driven dashboards have trouble agreeing on what their Top Ten Most Important Customer/Client 80/20 analytics should be.

That’s not good because Big Data promises to redefine the fundamentals of the 80/20 rule. What happens to innovation and segmentation when serious organizations are challenged to assimilate and integrate 10X, 100X or 1000X more information about customers, clients, prospects and leads? Should management refine and dig deeper into existing 80/20 KPIs? Or do those orders-of-magnitude more data invite revising and reframing a new generation of 80/20s? In other words, how much should dramatic quantitative changes inspire qualitative rethinking of the vital few that generate disproportionate returns?

At one travel services giant, 100X more data in less than two years utterly transformed the enterprise conversation around “loyalty.” Where repeat business and revenue had once been the dominant loyalty metrics, the firm began analyzing the overlaps and intersections between its “best” customers and social media and web comments about the company’s service. The company quickly adjusted its operational definition of “loyalty” to explicitly embrace and reward its “digital evangelicals” — customers who had enough of a virtual presence to be influencers. These customers were given perks, privileges and the power to offer certain promotions. The apparent result? A few hundred customers out of hundreds of thousands generated several millions dollars of additional top-line revenue. A digital presence 80/20 “cult” culled from the larger 80/20 loyalty “flock” yielded disproportionate profits remarkably fast.

Conversely, after identifying key traits of its breathtakingly wealthy private client practice, a global financial services firm spent millions seeking private clients with similar traits from their direct competitors. The combination of digital due diligence, processing power and predictive profiling required several terabytes — far more than the bank’s internal systems could handle. Reportedly, two pirated clients were all it took to repay the entire investment within a year. This Bigger Data venture profitably answered the question, “If this is what our 80/20 clients look like, who should we be targeting at our rivals?”

Of course, subtler and more nuanced 80/20 KPIs can be winkled out from expanding data sets. Remote diagnostics and maintenance networks empower industrial equipment firms to simultaneously ask and identify which 20% of its customers generate 80% of the most interesting and/or unexpected uses for the equipment? Might some of that novelty be patentable or protectable under some intellectual property regime? Simply by seeking to create, measure and assess 80/20 value creating segments, firms can harness 100X more information to new strategic thrusts. Instead of “data being the plural of anecdote,” 80/20 anecdotes emerge from the data: that is, committing to 80/20 KPIs inspires new analytic narratives.

For example, brand managers and advertising agencies alike increasingly make sentiment analysis part of how they assess public perceptions. So which 20% of external tweets, posts and presences account for 80% of sentimental shifts? Similarly, what sponsored content links to that vital 20%?

Marrying Moore’s Law to the Pareto Principle transforms Big Data into more actionable analysis. The best way to digitally discipline dataset mash-ups is identifying the 80/20 dynamics that the organization wants driving its differentiation. “What 80/20 analytic will matter most tomorrow?” is the challenge top management needs to both ask and rise to.

The most intriguing consequence I’ve observed is an emerging tension between managers and marketers who want to use Big Data and analytics to better customize their offering versus those who see 80/20 as a powerful segmentation exercise. Segmentation vs. customization seems destined to become one of the most interesting cultural, organizational, operational, marketing and innovation debates this decade. Ironically but appropriately, the best answers will be found in the fusion of Big Data and 80/20 analytics.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

You’ve Got the Information, But What Does It Mean? Welcome to “From Data to Action”

To Understand Consumer Data, Think Like an Anthropologist

To Avoid the Customer Recency Trap, Listen to the Data

Are You Ready for a Chief Data Officer?

Sometimes We Crave Attractive Leaders, Because They Look Healthy

In U.S. Congressional districts where life expectancy was 1 standard deviation below the mean, 2010 vote totals for physically attractive candidates were 3 percentage points higher than for unattractive candidates, on average, whereas in districts with high life expectancy, attractive candidates had no advantage, says a team led by Andrew Edward White of Arizona State University. A low life expectancy indicates a relatively high “disease threat” in a district, and an evolutionary perspective suggests that people facing disease threats show a greater preference for attractive, and thus healthy-looking, leaders.

Performance Management and the Pony Express

Microsoft has decided to dump the practice of rating individuals’ performance on a numerical scale – a decision I applauded in a recent post. I argued that such rating systems don’t accomplish the task managers expect from them, which is to accelerate the performance of their people. At best, they serve other goals: allocating compensation fairly, and aligning each individual’s goals with the values and strategies of the company.

However, even if these were sufficient goals, managers would still be frustrated by how poorly ratings-based Human Capital Management (HCM) systems achieves them. Here are the two intractable problems with today’s approach.

False Precision

All current HCM systems are based on the notion that a manager can be guided to become a reliable rater of another person’s strengths and skills. The assumption is that, if we give you just the right scale, and just the right words to anchor that scale, and if we tell you to look for certain behaviors, and to rate this person a “4” if you see these behaviors frequently, and a “3” if you see them less frequently, then, over time, you and your fellow managers will become reliable raters of other people’s performance. Indeed, your ratings will come to have such high inter-rater reliability (meaning that two managers would give the same employee’s performance the same rating) that the company will use your ratings to pinpoint low performers, promote top performers, and pay everyone.

Unfortunately there is no evidence that this happens. Instead, an overwhelming amount of evidence shows that each of us is a horribly unreliable rater of another person’s strengths and skills. It appears that, when it comes to rating someone else, our own strengths, skills, and biases get in the way and we end up rating the person not on some wonderfully objective scale, but on our own scale. Our rating of the other person simply answers the question: “Does she have more or less of this strength or skill than I do?” If she does, her rating is high; if she doesn’t, it is low. Thus our rating is really a rating of us, not of her.

Some companies have tried to neutralize this effect by training the manager how to look for specific clues to the desired strength or skill. This may result in managers becoming more observant, but it doesn’t turn them into better raters. This inability to rate reliably is so entrenched that even when organizations spend millions of hours and dollars training up a roster of experts whose only job is rating, they still don’t get the reliability they seek.

As an example, over the last few years every US state has done precisely that. Each state created a cadre of experts to evaluate, in extraordinary detail, the performance of teachers. One would have expected variation, with some good teachers, some not so good, and some differently good reflected in a range of ratings from the experts. But as The New York Times reported earlier this year, the results of these ratings have revealed alarmingly little variation. These expert raters are simply not very reliable.

Scour the literature and you will discover similar studies all confirming our struggles with rating the strengths and skills of others. Our ratings of others certainly look precise. They look like objective data. But they aren’t. They offer precision, but it is a false precision. So when we decide to promote someone based upon their “4” rating, or when we say that a certain choice assignment is open only to those employees who scored an “exceeds expectations” rating, or when we pay someone based on these ratings, or suggest a particular training course based upon them, we are making decisions on bad data. Earlier this month, in a spirited defense of the forced curve, Jack Welch advocated rating people on lists of competencies so that you can, in his words, “let them know where they stand.” This is a worthy sentiment, but given how poor we are as raters, competency ratings will only ever serve to confuse people as to where they stand. As they say in the data world: “Garbage in, garbage out.”

Bad practice, streamlined

We know how great managers manage. They define very clearly the outcomes they want, and then they get to know the person in as much detail as possible to discover the best way to help this person achieve the outcomes. Whether you call this an individualized approach, a strengths-based approach, or just common sense, it’s what great managers do.

This is not what our current performance management systems do. They ignore the person and instead tell the manager to rate the person on a disembodied list of strengths and skills, often called competencies, and then to teach the person how to acquire the competencies she lacks. This is hard, and not just the rating part. The teaching part is supremely tricky — after all, what is the best way to help someone learn how to be a better “strategic thinker” or to display “learning agility?” In recognition of just how hard this is, current performance management systems attempt to streamline the process by supplying the manager with writing tips on how to phrase feedback about the person’s competencies, or lack thereof, and then by integrating the competency rating with the company’s Learning Management System so that it spits out a training course to fix a particular competency “gap.”

The problem with all of this is not just the lack of credible research proving that the best performers possess the entire list of competencies, or any showing that if you acquire competencies you lack, your performance improves – or even that, as I described above, managers are woefully inaccurate at rating the competencies of others. No, the chief problem with all of this is that it is not what the best managers actually do.

They don’t look past the real person to a list of theoretical competencies. Instead the person, with her unique mix of strengths and skills, is their singular focus. They know they can’t ignore the individual. After all, the person’s messy uniqueness is the very raw material they must mold, shape, and focus in order to create the performance they want. Cloaking it with a generic list of competencies is inherently counter-productive.

Some say that we need to rate people on their competencies because this creates “differentiation,” a necessary practice of great companies. Of course they are right in theory — companies need to be able to differentiate between their people. But the practice is outdated. Differentiation cannot mean rating people on a pre-set list of competencies. These competencies are, by definition, formulaic and so they will actually serve to limit differentiation. True differentiation means focusing on the individual — understanding the strengths of each individual, setting the right expectations for each individual, recognizing the individual, putting the right career plan together for the individual. This is what the best managers do today. They seek to understand, and capitalize on the whole individual. This is hard enough to do when you work with the person every day. It’s nigh on impossible when you are expected to peer through the filter of a formula.

Telegraph Trumps Pony Express

In 1850 it took the average piece of mail five weeks to travel from St. Joseph, Missouri to the California coast. This was frustrating, since in 1848 somebody had discovered gold in the California hills and the wild and crazy rush was on. America was moving west and needed a much more efficient, streamlined way to communicate with its West Coast, full of riches. The Pony Express was the answer. Four hundred horses. A hundred and fifty small wiry riders. Two hundred stations, and the innovation of lightweight, leather cantinas to carry the mail westward. It was a fantastically complicated arrangement requiring careful forethought, detailed planning, and not inconsiderable daring. And, having woven together this complicated system, the inventors managed to streamline the process so well that, on its very first journey, what was once a five-week trek turned into a ten-day sprint from St. Joe to Sacramento. Speeches were made, fireworks fired, a great innovation was celebrated.

And then, Baron Pavel Schilling destroyed it all.

He didn’t do it deliberately of course. But he did invent the telegraph. And with that one invention, that one concept, he created a new worldview, one that rendered obsolete the entire system that they had worked so hard to streamline.

Our current performance management systems are the Pony Express — worthy efforts to streamline a labor-intensive, time-consuming, and unnecessarily complicated process. Who is our Baron Schilling? Well let’s give that role to Microsoft’s Lisa Brummel, the executive who declared “no more ratings.”

And then there’s the biggest question. What’s the telegraph? A topic for the next post.

November 22, 2013

Five Sources of Start-up Ideas

Does anyone dispute that 2013 has been the year of the tech company? LinkedIn has surged over 100%. Twitter and Zulily popped more than 70% and 80% respectively on the day of their recent IPOs. Even Facebook’s stock, once completely out of favor, has doubled in value over the past six months.

As prices of internet bellwethers reach stratospheric levels, more people are being enticed to start companies than ever before. Just one example: Roughly 16% of Stanford’s MBA Class of 2011 chose to start their own companies at graduation, eclipsing the previous high of 12% during the dot-com bubble.

That’s great for them. But as I’ve discovered recently, there are still countless more would-be entrepreneurs looking for a lightbulb moment before beginning their quest for fulfilling work, an independent agenda, and the potentially life-changing financial outcome that a start-up promises. In fact, when I interviewed my peers looking to become founders, the number one reason holding people back was the lack of a suitable idea. One remarked, “I have been working all my life, so funding isn’t a problem. I just don’t have any good ideas.” Said another: “I would start my own company tomorrow if I had an idea worth quitting my job for.”

To inspire the idealess, I’ve spent the past month investigating exactly where successful founders got their revelations. I surveyed 50 entrepreneurs at three different stages (pre-funding, growth, and acquired/gone public) and conducted detailed follow-up interviews with 15. Given that 90% of all ideas raised fit into one of the categories below, there’s a pretty good chance your next big thing will appear in the list.

Here are the top five sources of start-up ideas:

1. I experienced a pain point in my life and wanted to solve it. By far the most popular source of ideas among respondents was a frustration that the founder experienced in his or her personal life. Ever wonder how much your own problems might be worth? Ask Kent Plunkett, who founded Salary.com when hiring a secretary and finding himself unsure of what to pay. After building the world’s largest compensation information database, Kent eventually took the company public in 2007 at a valuation of $175M.

2. I met someone talented, and we started a company together. If you’re interested in starting a company, look at those around you, specifically at your workplace or school. Others have cautioned against starting companies with business school friends as a strategy for eventual success, but the data care to differ. Of the 39 companies started since 2003 and valued at over $1B by private or public market investors, almost half were started by founders who met at school. Close proximity of like-minded individuals seems to be a key catalyst for surfacing new ideas. Cofounders Corey Capasso, Andrew Fereneci, and Dan Reich first met at the University of Wisconsin, starting Spinback together many years later before the company was acquired by Buddy Media in 2011.

3. I have a special skill or passion, and I turned it into a business. Spend an hour conducting a written personal skills and passion inventory, and your next idea might be staring back at you. The founders in this category were intensely self-aware and looked for innovative ways to turn their work experience and hobbies into full-fledged businesses. Alexa von Tobel combined her passion for helping Millennials with her skill of articulating complex financial matters to start and raise more than $40M for LearnVest, an online financial planning company.

4. After working in an industry for a long time, I saw a customer need. Think your years slaving away at a corporate job will amount to nothing but a partially adequate 401(k)? If you use the experience to think hard about your customer’s unmet needs, you might be on the road to riches. The founders in this category worked in or around an industry for many years before starting a company directly related to that industry. Francois de Lame and Jennifer Fitzgerald amassed extensive experience in, and knowledge of, the personal insurance industry before starting KnowItOwl, an innovative online personal insurance navigator.

5. I researched many ideas and eventually narrowed it down to one. Savvy individuals are leveraging new sources of information, such as Quora and Hacker News, to conduct “top-down” research and use a data-driven process of elimination to arrive at a single business idea. Many were also very sophisticated in tracking proven business models and companies, with the goal of identifying breakout hits and applying them to new geographies. Founders Kimball Thomas and Davis Smith saw the value of taking the Diapers.com model to Brazil. Their latest goal? To hit $1B in revenue in the next few years.

So what does this mean for your inner “wantrepreneur” looking to hit it big? If you’re stuck pining to start, stop. Instead, extract start-up ideas from the fertile sources around you, and begin conducting small experiments to validate your hypotheses. Keep your head down and your momentum up, and with a little luck, you might just be onto the next big thing.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers