Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1505

December 2, 2013

If You’re in Over Your Head at Work, Try an S.O.S.

“I’m in over my head.” How often this thought has crossed my mind.

If you’re ambitious, this will happen to you a lot. It has with me: in every single job.

You reach a plateau. You are no longer enjoying the feel-good effects of learning so you jump from one learning curve to the next. And at first, your progress is slow: everything’s coming at you way too fast. What was I thinking? you wonder. Say hello to risk-taker’s remorse.

In most instances, if you give yourself six months, which the 10,000-hr rule suggests you need, you should find yourself happily afloat.

But what if you really are in over your head? Really.

Maybe your ego cashed a check your skills couldn’t cover; or you looked the part, so you got the promotion. Perhaps the problem you were hired to fix is much bigger than anticipated, or you’ve jumped into what you thought was a fresh-water lake only to discover you are swimming with sharks.

Before you drown, send out an SOS: stop, organize, secure. Regardless of how you got here, do not make it worse by acting without thinking and moving uncontrollably, such as sending out e-mails you haven’t slept on or vetted thoroughly. As uncomfortable as it may feel, don’t just do something — stand there. When you stop, you conserve emotional and physical reserves and preserve your political capital. Next, organize, assessing the situation and appraising what you need to do to regain your buoyancy. How far are you from the shore? How deep is the water? How close is that thunderstorm? Do you need swimming lessons, or a lifeguard?

As for securing what you need to succeed, in the best of situations, you’ll be able to ask for and get the help you need. When I started in equity research, I didn’t know how to craft a persuasive investment thesis or build a financial model. In retrospect, I was flailing (working all the time even when I wasn’t working, for example) but there were lifeguards on duty – in a supportive boss, colleagues that were ceaselessly helpful, and salespeople who were confident that I would be a rock star analyst. They threw me a lifeline every single day, and I eventually figured it out. Provided you have a team that wants you to succeed, it will take hard work but you can keep your head above water.

Even in a less trusting work environment, help from the right people and the right places can make a difference. This is what happened to me at one bank where I worked as an analyst – my skills were there, but I had colleagues who for their own reasons did not want me to succeed. The combination of an internal sponsor and an external coach made all the difference.

But there will be times when you won’t know how deep or choppy, or shark-infested the water is. No matter how good a swimmer you are, when the sharks are circling, you are dead meat. Sometimes then, the only way not to drown is to get out of the water. I’ve had that a time or two in my career – we all have. It’s just part of an ambitious career.

To paraphrase T.S. Eliot, if you aren’t in over your head, you can’t know how tall you are. The best will dive where no one is swimming — or wants to swim. Swimming in unexplored waters means you will sometimes get in over your head. Like I am right now with the D^4 conference I’m planning for 2014. I announced it before I even had a venue. I haven’t ever put on a conference of this magnitude before. Which has left me gasping and thrashing. Fortunately, I’ve swum a lot of laps, and I’ve got the one essential safety device for explorers in deep water: the life jacket of a network, whom I will humbly ask for help.

Living an ambitious life means being perpetually in over your head. You’ll be fine as long as you keep your S.O.S. at the ready.

The Human Brain Is Too Weak for Gossip

William Shakespeare, speaking through one of his characters in The Comedy of Errors, articulated a very important psychological insight: “Ill deeds are doubled with an evil word.” Words act as multipliers — they’re powerful. And if the Bard had wanted to give management advice, he’d certainly have warned us about the pernicious impacts of gossip in the workplace.

Gossip is evaluative talk among familiars about a third party who is not present. Surely it is a bit of stretch to characterize gossip as “evil.” Yet a number of the world’s most prominent religions and philosophies explicitly have dissuaded their adherents from engaging in the activity — sometimes even characterizing it as sinful. In Leviticus, one finds, “Thou shalt not go up and down as a talebearer among thy people.”

Similar remarks are found the Koran. Confucius, in The Analects, is reported to have said, “To engage in gossip and spreading of rumors is to abandon virtue.” The same sentiment appears in the writings of ancient Stoic philosophers and in modern-day self-help books. The thought is everywhere — and for good reason.

The old philosophers and sages understood instinctively what contemporary psychology is more formally demonstrating: our beliefs are not always established and maintained in the most rational ways. To begin with, when we encounter new information, there is good evidence that our mind’s default mode is first to assume it is true. Only when the receiver has sufficient motivation and time to reflect on the information, will it potentially be tagged in the memory as false. Until then it’s stored as if it were true. With gossip, that’s clearly dangerous.

Gossip becomes even more worrisome when one starts to appreciate other ways in which our mind is fallible. For instance, we sometimes mistake the source of our memories and the context in which they were encoded.

I recently told a class about my vivid recollection of the day the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded. I vividly remember my elementary school gym teacher gently breaking the news to my fellow six-year-old classmates and me. After I recounted this story, one student commented that I looked rather old for my age. It turns out that the Challenger exploded in 1986 when I was twelve years old and in middle school. (It took a bit of Googling to convince me that my memory was mistaken.) You could just as easily “remember” something you overheard from the office’s arch-gossiper as coming from a truly credible source.

The multiplying effect of gossip gets more troubling when beliefs formed through it shape subsequent perceptions. Our minds attend selectively to information that supports already existing beliefs, and to discount information that goes against our beliefs. That phenomenon — confirmation bias — has been documented in countless psychological studies. (Mind you, anyone who’s witnessed discussions around contentious political issues — e.g., gun control or Obamacare — should have more than enough data to conclude that people selectively choose their “facts.”) By implanting beliefs, therefore, gossip can dangerously shape subsequent perceptions.

Gossip may provide momentary entertainment to some people. That part is clear. What is less apparent to them, I suspect, is that it also can alter their minds and hence their realities. Gossip can blow up start-ups and corrode morale in large companies. It is, as Shakespeare might say, a most calamitous evil.

Factory Workers Are More Productive When Managers Can’t See Them

In a factory where mobile data cards were being made, hanging a curtain to conceal workers from managers’ view increased production by 10% to 15%, according to an experiment by Ethan S. Bernstein of Harvard Business School. The curtain prevented distractions and allowed workers to test productivity-boosting ideas before explaining them to managers. Managers need to consider not only their individual workers’ privacy on the job but also group privacy, Bernstein says.

Why China Loves the Internet

The size of the Chinese Internet is staggering. There are almost 600 million Internet users in China now, more than in any country in the world — next highest is the U.S, with 254 million. That’s just 44% of the Chinese population compared to 81% in the U.S., so this gap will continue to grow. For example, if every province in China achieves a 50% penetration rate, 135 million new Internet users will come online. 78.5% of Chinese users access the web from their mobile devices (compared to 63% in the U.S.), and many of the most popular services, like WeChat, exist only as a mobile application.

Chinese users are also more engaged than Americans are. Already in 2011 the Chinese spent more time on the Internet than watching TV, while in the U.S. this crossover is predicted to happen only this year. More than 75% of them regularly contribute content online, but only less than a quarter of Americans do. And users in China are probably going to spend more money on e-commerce in 2013 than Americans will. A recent online shopping holiday brought in more than $5.75 billion in one day, compared to last Cyber Monday’s $1.5 billion.

There are many reasons China outdoes the rest of the world in online use. The first set is related to what is happening in the offline world there:

Existing media are weak. Because their media are censored, people in China turn to the Internet to get a deeper understanding of what’s going on in the country and see what other people think. Also, if you ask an average Chinese person about TV, you will often hear: “Oh, it’s really boring. There are so many channels, but often there is nothing to watch.” So, they turn to the Internet for their entertainment.

People are on the move. In 1990 only a quarter of the Chinese population lived in cities. Today, half does. This means that over 300 million people moved far away from the people with whom they grew up, and the Internet is critical to reconnecting them with their roots. This will only continue. The Chinese government plans to move 250 million rural residents into newly constructed towns and cities by 2025.

Income inequality is growing. China’s economy is growing really fast and so is inequality. For example, in 2013 there were 315 people in China who had more than a billion dollars, up from zero in 2003. Those who have grown wealthier than their peers in a short period of time want to establish relationships with others of similar economic stature, and to do that they often turn to the Internet.

Kids are lonely. The one-child policy has been around for over 30 years. Most kids grow up without siblings. They come home from school and the only people they see are their parents. They want to hang out with people their own age, so they are glued to the Internet.

And some adults are lonely too. Due to the one-child policy there are many more men than women in China, particularly in rural areas, so competition in the marriage markets is intense and some men have to work really hard to find a spouse. The Internet offers a great opportunity to do that.

Second, people in China are drawn to the Internet because they have so many choices of engaging sites and services. Even though they cannot access Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, many blogging services, and some Google services, they can access multiple Chinese equivalents. In the U.S. people pretty much only use Facebook to interact with friends, but in China they can choose between QQZone, WeChat, and Renren, to name a few. To interact with celebrities and strangers, Americans tend to go to Twitter. In China, people can choose to go to Sina Weibo, Tencent Weibo, Alibaba Weibo — as well as a ton of little Weibos. The same goes for social gaming — Tencent, Netease, Sina Weibo, and others provide many social games for users to play. There are also many sites for which there’s no equivalent in the U.S. For example, there are sites such as 9158.com or yy.com where you go and sing for or with other people. Such sites provide much-needed entertainment and allow people to connect with others easily.

The third set of reasons why the Internet is so big in China is that it connects shoppers to businesses in unique ways:

You can find a large selection at low prices. In China, the five largest retailers account for only 10% of the total retail market, so most customers have to buy items in mom-and-pop stores. Since these do not offer great variety, or low prices, customers go on the Internet to get what they need.

Brands are weak. Some China specialists I interviewed in the country estimated that 330,000 new products are introduced every year in China. Most of them are unbranded, and most of them fail. Consumers don’t have enough information about these products, so those who can are turning to the Internet to discuss these products with others online. In fact, More than 40% of Chinese e-commerce shoppers first saw information about a product on a social media site before buying it.

TV advertising is expensive. Since the state has a monopoly on television — and on TV advertising rates — companies often complain that it is too expensive. The Internet often offers a more cost-effective advertising solution. Firms not only advertise online, but they also pay online opinion leaders to drive their product reviews.

Same-day delivery is common. E-commerce really works in China largely because in many of the 160 cities with populations over one million, you can get extremely cheap same-day delivery. Buying online is so much more fun when the item you ordered in the morning is already on your doorstep in the afternoon. This will only get better as some Chinese startups are gearing up to deliver products within 24 hours to any city in China within the next eight years.

We should expect the Chinese Internet to continue to draw vast numbers of additional users in, while finding many more ways to engage them more deeply. Chinese companies will accelerate this by constantly trying something new—often in partnership with each other. This is partly because engineering costs are low and partly because there is less of a fear of failure. If Chinese Internet companies introduce something and it does not work, they just scrap it and move on. I believe this approach will allow them to innovate far beyond what American companies like Facebook and Twitter are doing right now.

And if these trends do continue, it will not be long before we see broad adoption of Chinese Internet products in the U.S. and around the world, just as we saw with non-digital products in the past. With such innovation and variety, that can only be a good thing for consumers.

China’s Next Great Transition An HBR Insight Center

If You Want to Change the World, Partner with China

Ten Predictions for China’s Economy in 2014

How Chinese Companies Can Develop Global Brands

The Chinese Steamroller Is Already Sputtering

November 29, 2013

I Wasn’t Hiding From You, Boss. I Was Just Being Productive.

I'm sitting here, alone, in HBR's library, writing about how my decision to relocate from my open workspace is making me much more productive. It's not merely because it's quieter; research from Harvard Business School professor Ethan S. Bernstein suggests that employees can actually be more productive when they're outside the gaze of their managers — and that being outside this gaze can, in the end, make your company more transparent. In one study, Bernstein hired Chinese-born Harvard undergrads to embed themselves as workers on a Chinese manufacturing floor. When managers were around, the frontline staff did everything by the book. When they weren't, employees showed the Harvard students tricks they had developed to work faster, more easily, or more safely. Why didn't they show their bosses these shortcuts? They didn't want to rock the boat or take precious time away from doing the work in order to explain the work. "Everyone is happy," explained one worker. "Management sees what they want to see, and we meet our production quantity and quality targets."

In another study, "simply hanging a curtain increased production by 10 to 15 percent." And while Bernstein is careful to say that companies shouldn't just go around building walls, he does urge managers to note that "this race to full observability of everything can have unintended consequences."

Managing the End of PolioThe SurgeWired

Oh, you think you have a management challenge? This remarkable and inspiring article by Matthieu Aikins follows a group of World Health Organization workers who are on a quest to eradicate polio — a disease that afflicted 223 people last year, down from 350,000 cases in 1988. Sure, it may seem as though they're close to achieving their goal. But then there's the small issue of trying to vaccinate children in the region where Afghanistan meets Pakistan, an area that’s tightly controlled by the Taliban. While Taliban leaders in Afghanistan have been more amenable to the program, those in Pakistan have not — 22 people have died after attacks on the vaccination program. Aikins traces both the history of how diseases like smallpox were eradicated amid Cold War tensions and the unique issues facing vaccinators today, including the hurdles that a 25-year-old woman named Rana faces as she manages seven teams charged with vaccinating 13,962 children during National Immunization Days.

Cats Squeezing into Tiny Boxes and … Javad Zarif?This is Bigger Than a Nuclear Deal The Atlantic

Uri Friedman looks at the nuclear deal with Iran and sees a new era in Iran-U.S. relations, a development made possible not just by diplomatic negotiations, but by…YouTube? His argument is worth hearing out. Coming after decades of failed attempts at communication — including prank phone calls, snail mail, faxes (remember those?), and even a bizarre case in which a senior Iranian commander texted the Iraqi president and asked that the phone with the text message be handed to a senior member of the U.S. military – the disintermediating power of the internet has finally reached into the halls of power. Theoretically, governments already possessed the power to speak to their people. It was the first Roosevelt, after all, who called the U.S. presidency a bully pulpit. But today, when an Iranian leader can speak directly to the American people on YouTube, those international messages are less likely to get lost in translation. —Sarah Green

Oh, This Is RichClinging to Outlook, Only 25% of Yahoo Employees Willing to Eat Mail "Dogfood"AllThingsD

Enjoy this leaked email from Yahoo that begs – nay, pleads with, in rollicking and at times painfully annoying language — employees to please finally switch from Outlook to a Yahoo mail product for job-related work. The urgency? The company asked workers to make the move earlier this year and a mere 25% did, a fact that doesn't bode well for the company and one of its signature products (email). After mocking Outlook — "it doesn't feel like we are asking you to abandon some glorious piece of communications nirvana" – execs Jeff Bonforte and Randy Roumillat offer Outlook defectors the promise of early access to features. "Feeling that little tingle? Take a deep breath, you can do this," the duo implores. Kara Swisher at AllThingsD finds the memo utterly delightful. Others declare it to be "rambling" and "one of the finest examples of interoffice literature ever leaked." Get ready, Katie Couric.

To Tweet During or After Twerking?What Pepsi Discovered by Monitoring Millennials During the VMAsAdWeek

Everyone knows there’s a big difference between someone who's 12 and someone who's 34, or even between an 18- and a 28-year-old. But for many marketing purposes, they all get lumped together as millennials, presumably more similar to one another than to Gen Xers or Baby Boomers. When Pepsi took a more-detailed look at millennials’ behavior during the recent MTV awards, though, it found a marked difference between the 18-to-26-year-old crowd and the 27-to-36-year-olds. The younger group shifted immediately from the TV to their smartphone screens during Miley Cyrus’s "twerk-tastic" duet, while their older counterparts just kept on watching, waiting until after the show to go on social media (perhaps suggesting that not all millennials make it a habit to carry their phones in their hands at all times, or maybe indicating something about how the romance of multitasking wanes with age).

Perhaps more important, Pepsi’s marketers discovered that the show’s appeal ebbed and flowed at different times for different groups, holding or failing to hold people’s attention in varying degrees. The lesson: It’s important to maintain a brand message throughout a show, rather than just in the traditionally more valuable (and pricier) beginning and end slots. —Andrea Ovans

BONUS BITSBlack Friday, from the Archives

Crush Point (New Yorker)

I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave (Mother Jones)

Black Friday Is a Bunch of Meaningless Hype, in One Chart (Washington Post)

How to Start Thinking Like a Data Scientist

Slowly but steadily, data are forcing their way into every nook and cranny of every industry, company, and job. Managers who aren’t data savvy, who can’t conduct basic analyses, interpret more complex ones, and interact with data scientists are already at a disadvantage. Companies without a large and growing cadre of data-savvy managers are similarly disadvantaged.

Fortunately, you don’t have to be a data scientist or a Bayesian statistician to tease useful insights from data. This post explores an exercise I’ve used for 20 years to help those with an open mind (and a pencil, paper, and calculator) get started. One post won’t make you data savvy, but it will help you become data literate, open your eyes to the millions of small data opportunities, and enable you work a bit more effectively with data scientists, analytics, and all things quantitative.

While the exercise is very much a how-to, each step also illustrates an important concept in analytics — from understanding variation to visualization.

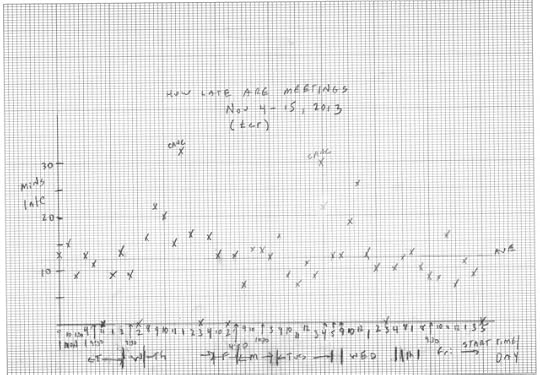

First, start with something that interests, even bothers, you at work, like consistently late-starting meetings. Whatever it is, form it up as a question and write it down: “Meetings always seem to start late. Is that really true?”

Next, think through the data that can help answer your question, and develop a plan for creating them. Write down all the relevant definitions and your protocol for collecting the data. For this particular example, you have to define when the meeting actually begins. Is it the time someone says, “Ok, let’s begin.”? Or the time the real business of the meeting starts? Does kibitzing count?

Now collect the data. It is critical that you trust the data. And, as you go, you’re almost certain to find gaps in data collection. You may find that even though a meeting has started, it starts anew when a more senior person joins in. Modify your definition and protocol as you go along.

Sooner than you think, you’ll be ready to start drawing some pictures. Good pictures make it easier for you to both understand the data and communicate main points to others. There are plenty of good tools to help, but I like to draw my first picture by hand. My go-to plot is a time-series plot, where the horizontal axis has the date and time and the vertical axis has the variable of interest. Thus, a point on the graph below (click for a larger image) is the date and time of a meeting versus the number of minutes late.

Now return to the question that you started with and develop summary statistics. Have you discovered an answer? In this case, “Over a two-week period, 10% of the meetings I attended started on time. And on average, they started 12 minutes late.”

But don’t stop there. Answer the “so what?” question. In this case, “If those two weeks are typical, I waste an hour a day. And that costs the company $X/year.”

Many analyses end because there is no “so what?” Certainly if 80% of meetings start within a few minutes of their scheduled start times, the answer to the original question is, “No, meetings start pretty much on time,” and there is no need to go further.

But this case demands more, as some analyses do. Get a feel for variation. Understanding variation leads to a better feel for the overall problem, deeper insights, and novel ideas for improvement. Note on the picture that 8–20 minutes late is typical. A few meetings start right on time, others nearly a full 30 minutes late. It might be better if one could judge, “I can get to meetings 10 minutes late, just in time for them to start,” but the variation is too great.

Now ask, “What else does the data reveal?” It strikes me that five meetings began exactly on time, while every other meeting began at least seven minutes late. In this case, bringing meeting notes to bear reveals that all five meetings were called by the Vice President of Finance. Evidently, she starts all her meetings on time.

So where do you go from here? Are there important next steps? This example illustrates a common dichotomy. On a personal level, results pass both the “interesting” and “important” test. Most of us would give anything to get back an hour a day. And you may not be able to make all meetings start on time, but if the VP can, you can certainly start the meetings you control promptly.

On the company level, results so far only pass the interesting test. You don’t know whether your results are typical, nor whether others can be as hard-nosed as the VP when it comes to starting meetings. But a deeper look is surely in order: Are your results consistent with others’ experiences in the company? Are some days worse than others? Which starts later: conference calls or face-to-face meetings? Is there a relationship between meeting start time and most senior attendee? Return to step one, pose the next group of questions, and repeat the process. Keep the focus narrow — two or three questions at most.

I hope you’ll have fun with this exercise. Many find a primal joy in data. Hooked once, hooked for life. But whether you experience that primal joy or not, do not take this exercise lightly. There are fewer and fewer places for the “data illiterate” and, in my humble opinion, no more excuses.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

You’ve Got the Information, But What Does It Mean? Welcome to “From Data to Action”

How is Big Data Transforming Your 80/20 Analytics?

To Understand Consumer Data, Think Like an Anthropologist

To Avoid the Customer Recency Trap, Listen to the Data

Tackling the “Hotspotter” Patient Challenge

A fascinating business dynamic will unfold as health care providers in the United States shift from a reimbursement system that has historically paid for procedures performed to one that rewards population health — providing the total care of a community at a fixed cost and improving its members overall health. This means that to a significant degree historic areas of revenue generation will become generators of losses. While it’s common in most for-profit and nonprofit businesses for centers of revenue generation to fluctuate in their productivity, a shift of this scale represents a sea change for the health care sector that it must face head-on. The concept is especially applicable to high-cost patients, sometimes referred to as “hotspotters.” In the United States, the top 1% of high-cost patients consumes a disproportionate 28% of total health care costs, and the top 5% of high-cost patients consumes more than 50%.

One reason for this phenomenon is that these patients, while costly, are also the source of a substantial amount of revenue and contribution margin. In today’s health care market, providers — hospitals, physicians, surgery centers, clinics — are paid for volume. And this comparatively small subset of patients is the source of extraordinary amounts of volume. We know, for instance, that hotspotters visit our system 41 times over a five-year period, on average, compared to six times for the average patient. As health care reform rolls forward and provider incentives move towards fixed payments, these high-cost and high-utilizing patients will become the five-alarm fire for all care providers for one simple reason: There will be no commensurate revenue offset. In the foreseeable future, what was once a profitable or breakeven proposition will become a significant financial liability.

At Intermountain Healthcare, we are proactively changing the way we provide care for high-cost patients. A nonprofit serving Utah and southern Idaho, Intermountain has a network of 22 hospitals and 185 clinics and employs 1,000 physicians and more than 34,000 employees in total.

Although we have much ground still to cover, we have vastly improved our understanding of high-cost patient characteristics, accumulated extensive knowledge of hotspotter perceptions from a comprehensive survey that we recently conducted, and learned about optimal organizational structures required to realize change.

As the largest health care provider in Utah, Intermountain has always had an enhanced commitment to population health. The answers to these core questions serve as our compass: What is best for our patients and the community we serve? And, how can we provide the highest quality care at the lowest appropriate cost?

These questions are at the heart of why Intermountain is so interested in addressing the current challenges of high-cost patients, and we have invested substantive efforts and resources in learning more about them. Our findings include the following:

One percent of Intermountain’s patients used 24% of the total amount we spent on patient care between 2008 and 2012.

Five percent of Intermountain’s patients consumed almost 51% of our total costs over the same time period.

High-cost patients experience high rates of turnover. Less than 10% of the top 1% of high-cost patients remain in that category the following year, and less than 0.5% of these same patients remain in that category for five consecutive years.

The top 1% of high-cost patients has a 75:25 split of adult:pediatric patients. (Intermountain has an entirely different team looking at high-cost pediatric patients.)

The top 1% of high-cost patients experiences a mortality rate of 26% over a five-year period.

The unfortunate reality is that despite all the frequent and costly care these patients receive, they’re not necessarily always getting well. While clearly a work in progress, here are some lessons learned about our top 1% of high-cost patients:

Understanding the patient perspective is an essential part of identifying potential solutions. Over the past six months, we completed a comprehensive survey of our high-cost patients to learn and understand more about their experiences and perceptions. Some of the findings were expected, but others were surprising.

Among the expected findings were the following: Patients said their care is not well coordinated and that they need more help to understand and follow up on their complex care plans. Although grateful for the care they received, they most often described their quality of life as fair to poor.

We were surprised to learn that by almost a 2-to-1 margin patients attributed themselves, not the care they received, as the more significant impediment to their improvement. Fifty-seven percent indicated lack of self-care as a contributing factor, and an even higher percentage (63%) identified depression or other mental health concerns. The findings reveal the critical need for self-care educational and motivational assistance in addition to improvement of system structure and processes.

The good news is we can analyze our care for these patients and develop ways to improve their care while potentially reducing its costs — which is precisely what we are attempting now. Almost all of our high utilizers have a chronic disease and many have several:

Seventy-seven percent have at least one of these chronic conditions: cardiovascular, mental illness, lung disease, renal disease, diabetes, liver disease, cancer, stroke, or some kind of paralysis;

Forty-six percent have two or more of those conditions;

Twenty-three percent have three or more of those conditions.

For almost all of them, a major problem is following the ever-growing list of recommendations from all the specialists they see; it is more than most can do.

Numerous and varied targeted interventions will be required to address the different subgroups of the top 1% of high-cost patients. The organizational challenge we face is that the top 1% of our patients represents about 20,000 patients — a large population to tackle at once.

We know, for instance, there were 89 patients who remained in our top one percent of high-cost patients for five consecutive years. Those 89 patients consumed approximately $40 million in care. Almost $11 million, or over a quarter of the total, was related to renal care. We learned that three clinic sites in the system providing dialysis care were responsible for the majority of cost.

This kind of analysis provides actionable information, which can result in changes to the provision of care. In addition to bringing transparency to the care and disproportionate costs associated with a small number of patients, the analysis triggered in-depth case management review, which revealed some waste as well as confirmation of appropriate care. Some patients had numerous attending physicians whose care was poorly coordinated between providers. In some cases, there was no point person or coordinator and specialists were not communicating sufficiently. In other cases, data revealed that costs were driven by extraordinarily high medication costs that were medically necessary and represented life-sustaining treatment.

Surprisingly, end-of-life care was not a significant factor, accounting for approximately 8% (last six months of life), and 12% (last year of life), respectively, of all costs incurred by the top 5% of high-cost patients.

Appropriate organizational structure is imperative to realizing change. We learned more about the organizational structures required to implement change across a large, integrated, health care operation. Each hotspotting committee has a charter, which is a frequently updated document that describes its purpose, participants, scope, decision-making authority, and objectives.

Initially, we created a steering committee comprised of key stakeholders, including representatives from our central headquarters, senior doctors from our medical group, officials from SelectHealth (our integrated health insurance provider), and leaders of various operating areas. This committee provides valuable input into our efforts as well as vital channels for information sharing across the system. The sheer number of concurrent system initiatives addressing the redesign of care requires extensive coordination and collaboration. Without it, we duplicate resources, waste time and confuse patients with overlapping programs. This group has provided us greater uniformity in how we approach the complex challenges of improving care for high-cost patients.

Soon thereafter, we established a “hotspotting” executive committee, which provides executive sponsorship, direction, and orchestration of analysis and implementation efforts system-wide. This committee is comprised of a half-dozen senior leaders, including Intermountain’s vice president for health care transformation and vice president of clinical operations, who is also our chief nursing officer. One of the revelations of the first year of our efforts was that executive ownership and sponsorship are essential to making substantive change. In this era of reform, there are so many competing programs and initiatives for limited resources that programs lacking executive sponsors often can’t warrant the attention necessary to succeed.

Finally, we created a “hotspotting” analytics committee — comprised entirely of analysts — to broaden our understanding of how the high-utilizing patient population is being served: the characteristics of their health conditions; the nature and extent of their care (including where it was provided and by whom); and the effectiveness of its coordination. The contributions of these analysts to our efforts to redesign care processes cannot be overstated. They provide the bulk of support for complementary committees across the system dedicated to redesigning care processes. Their expertise is helping to generate uniquely valuable insights. (For example, the coding we use to identify high-cost patients and subsets of that segment is pages long.) Our analysts maintain data integrity across the organization and prevent the respective committees from duplicating efforts.

We now have two pilot projects in the works that will help us better serve the 5% of our patients who use so many services.

An integrated-care-management pilot will aid us in refining our overall strategy for managing adult care. It will help us use best practices more effectively, improve the way we manage transitions and handoffs between providers, prevent unnecessary emergency department admissions, and increase our coordination with community resources.

A special-care-clinic pilot located centrally in Salt Lake City is designed to assist the whole person and not just specific medical conditions. The clinic will provide personalized adult primary care to help high-utilizing patients increase their access to services like primary care, home health, mental health, and medication management.

We anticipate launching additional pilot projects designed for future hotspotter subgroups.

We’ve demonstrated historically that when we implement evidence-based practices, we not only improve clinical outcomes but also do so at a lower overall cost to the community. That’s the key to making reimbursement for population health work. It’s not restricting care to reduce costs, because restricting care leads to worse outcomes. It’s focusing on the outcomes.

In a very real way, those who were initially seen as the problem, point the way to making population health work. The key is outcomes, which is what health care should have been about all along.

China’s Economy, in Six Charts

China’s economy has entered a critical phase. Since the country opened its doors in 1978, the economy has witnessed tremendous growth. Its gross domestic product has surged from less than $150 billion in 1978 to $8,227 billion in 2012 (see “China’s GDP” chart below). In the process, more than 600 million people have escaped poverty. This is a marvelous achievement for any country, let alone one as geographically large and populous as China.

China’s business landscape has also undergone a transformation. It boasts 85 companies in the Global Fortune 500 list of the world’s largest corporations. Foreign investors have flocked to the country’s shores as many of the world’s largest manufacturers have established operations there. Many iconic brands dot the shopping districts of the major cities. Despite these impressive achievements, there is still plenty of room for catch up, with China’s per capita GDP only a fifth of the U.S. level (see “GDP Per Capita” chart below).

China’s growth has come largely from a rising labor supply and rapid capital accumulation. While these factors will remain important, in the next decade China must put greater reliance on productivity growth — the ability to get greater output from existing labor and capital stocks. The government has emphasized the need to rebalance growth, focusing on raising domestic consumption and living standards. However, transitioning to a more economy, while maintaining current growth rates, will not be easy.

Decomposing China’s GDP growth over the last three decades, we assessed the drivers behind it such as labor, capital, and total factor productivity (TFP), which is a more precise measure of efficiency in the use of inputs other than labor and capital. As shown in the chart “China’s Sources of Growth” below, capital has been the key driver of China’s growth over the last three decades. Capital accumulation accounted for 6.9 percentage points of the 10.5 percent average annual increase in GDP in the last decade, 5.7 percentage points of the 10.1 percent average annual increase in GDP in 1990 to 2002, and 7.2 percentage points of the 9.7 percent average annual increase in GDP in 1979 to 1989.

Meanwhile, the contribution of labor to GDP growth is decreasing. It contributed 1.4 percentage points of GDP growth in 1979-1989, 0.5 percentage points in 1990-2002, and 0.3 percentage points in 2003-2012. Because of the one-child policy, China’s population growth is slowing. Moreover, the population is aging and the size of the labor force is set to plateau in 2016 (See “China’s Labor Market” chart below). A shrinking labor force will be a drag on growth. In fact, China is already experiencing a labor shortage: Wages are rising and it is losing its labor-cost advantage to other developing countries.

During the last decade, China relied increasingly on investment to boost its economy. This was obvious during the financial crisis in 2008, when the government invested about 4 trillion RMB to enhance growth. Such investments might not be sustainable in the long term. Policy makers and scholars generally agree that China must rebalance its economy toward a consumption-driven development model. This is the overarching goal of China’s 2010-2015 plan.

China will find it hard to sustain rapid rates of economic growth in the future. Our research suggests that if China wants to lower the investment ratio to below 40% of GDP by the end of next decade, while keeping the rate of economic growth above 8 percent (essential for maintaining full employment), it must improve the growth rate of productivity. In the most optimistic scenario, where GDP growth during the next decade is sustained at the same rate as during the last decade (10.5%), annual productivity growth would need to jump from 3.3% to 5.6% (See the “How Much Productivity Is Needed to Drive Future Growth?” chart below).

Since China opened up, the nation has travelled through different stages of development. As the impact of the labor bonanza and capital-led phases begins to fade, productivity growth in China must increasingly come from the quality of innovation and management expertise at the organizational level. Witness the rapid growth in US productivity levels in the 1990s and 2000s in sectors such as retailing. That growth was driven largely by the increased use of information technology in customer analysis and supply chain optimization.

China, too, needs more technological innovation. China has almost tripled the share of its GDP devoted to R&D over the past 20 years, from 0.65% in 1993 to 1.97% in 2012 (See the “R&D Expenditure in China” chart below.) although it still remains below that of the US. This is attributable to China’s national technology strategy of “market access in exchange for technology.” The strategy stems from China’s desire to acquire new technology through technology transfer or foreign direct investment, and assimilate it through learning, imitation and other means. The ultimate goal is the ability to innovate independently. Chinese firms have realized that they cannot just purchase core technologies; they must create them on their own.

Franz Kafka once said that productivity is about being able to do things that you were never able to do before. By addressing the productivity imperative now, China, too, can continue doing things it has never done before.

China’s Next Great Transition An HBR Insight Center

If You Want to Change the World, Partner with China

Ten Predictions for China’s Economy in 2014

How Chinese Companies Can Develop Global Brands

The Chinese Steamroller Is Already Sputtering

Making #GivingTuesday a Movement

Most of the traditions we associate with the holiday season – stuffing turkeys, decorating trees, burning candles – are rituals that have taken hold over decades if not centuries. Some, like Black Friday and Cyber Monday, are habits gained more recently thanks to the power of consumer goods advertising. But what if people decided they’d like to have a new tradition, and one not centered on shopping but in the deeper, soul-satisfying spirit of the holidays? Could we start a movement to create one?

Some of us decided to try, and last year for the first time we put out the idea of “Giving Tuesday” – or, more properly styled for the age of social media, #GivingTuesday. The point is to follow the binge-buying of the Friday and Monday after Thanksgiving with a day of gift-giving to charities.

Within just 70 days, a coalition of nonprofit and corporate entities came together to agree on the mission and create a communications infrastructure, and more than 2,700 organizations, representing all 50 US states, registered as partners on the #GivingTuesday website. By signing on, partners were committing to launch some kind of initiative under the #GivingTuesday banner, and gaining resources from the site to help them do that.

The leaders of these organizations immediately got the concept that the philanthropic community stood to benefit by converging on a day like this, in the same way that retailers (even though they compete aggressively) all take part in and benefit from Black Friday. With every project, they are spreading the word through their networks, and the connection to #GivingTuesday becomes more valuable. At the same time, they appreciated that their participation did not require them to spend on messaging over and above what they had been planning. Because the timing and tagline of #GivingTuesday can easily be incorporated into existing campaigns, even thinly-stretched charities can use it to refresh their message and increase awareness.

It wasn’t only the charitable institutions whose attention was captured. In the latter half of November 2012, there were more than 800 media hits for #GivingTuesday. On Twitter, the hashtag trended to number one on Tuesday, November 27. (Not bad for a movement that had first said hello to the Twitterverse in August.) Across all kinds of platforms, individuals from nonprofit development staff to celebrities to CEOs helped spread this compelling idea.

And most importantly, more giving took place. Many partners reported higher donations – several said their online giving was up by 50 percent on #GivingTuesday. There is not a development team or nonprofit board in the world that wouldn’t perk up at that number.

My organization, the National Philanthropic Trust, has held a series of events in Philadelphia for fundraising organizations who want to learn more about how to benefit from #GivingTuesday. We were pleasantly surprised when approximately 50 percent of the people we thought to invite to the first session showed up – a rare turnout. Six months later, the number of attendees was almost triple, as regional nonprofit and community leaders caught wind of the movement.

Everyone connected with #GivingTuesday is happy to see excitement growing as our next big day –December 3, 2013 – grows near. Signs are promising that this is a happening more people want to participate in, and that might just take hold as a lasting tradition. At the same time, we know a new movement requires constant infusions of fresh energy to build its momentum. As our partners leverage the power of #GivingTuesday to capture the public’s imagination and lend excitement to acts of generosity, here are a few things we’re working to do:

Make it easier. With the benefit of time, hindsight, and sustained enthusiasm, #GivingTuesday has expanded its resources for partners. This year, there are training and workshop opportunities, online tools and kits, compelling videos, and sample Tweets. #GivingTuesday has made the “lift” as light as possible for organizations that want to tap into the movement to amplify their normal year-end activity.

Take it global. International giving by US-based donors is the fastest-growing piece of the giving pie, according to Giving USA. As international charitable organizations learn about #GivingTuesday and try to leverage the idea with their stakeholders, they’re not just attracting US donors who are aware of the movement, but raising the profile of #GivingTuesday regionally and around the world. Already, communities in Canada, Australia, and Mexico have launched efforts to spread #GivingTuesday particularly in those countries.

Encourage innovations on the theme. The point of #GivingTuesday shouldn’t be to hand partners a playbook and insist they follow it to the letter. We know creativity inspires creativity—and saw that when individuals, families, charities, and businesses grabbed this idea and ran with it. One of my favorite variations came from Dress for Success, a charitable organization that gives lower-income women professional clothing so they can walk into job interviews and office settings more confidently. Playing on the name #GivingTuesday, they staged a #GivingShoesDay. As for this year, rumor has it we’ll see some famous couples spending #GivingTuesdates together, taking money they could have spent going out and instead staying in, and giving it to a favorite charity.

Learn from experience. #GivingTuesday developed case studies and metrics to capture what happened in 2012. As that effort continues, the objective will be to share what works throughout the network and collectively build on the gains being made. They say “a rising tide lifts all boats” and that is what #GivingTuesday aims to be.

The beauty of #GivingTuesday is this: you can make it whatever you want it to be. It is decentralized and therefore adaptable to existing or new efforts. It is a charitable organization’s online fundraising campaign and an opportunity to talk to your children about philanthropy; it is a grant from a Fortune 500 company and a bake sale to benefit a community theater; it is a simple act of kindness to a neighbor or stranger. #GivingTuesday only has to be about giving — people sharing what they have to help others and build stronger communities.

It’s part of American life that, as soon as Thanksgiving is over, it dawns on us all that there are gifts to be given. Probably it is inevitable that we will feel compelled to swing into action, and be drawn by the promise of bargains. Perhaps we just have to accept that Black Friday and Cyber Monday will be frenzied. But wouldn’t it be nice if, before getting any deeper into the holiday season, we could re-set the tone? Why not spend a day reflecting on the bounty we have, and enjoying the kind of giving that does our souls good?

The second #GivingTuesday will happen on December 3, 2013. For updates and related news, follow @GivingTues on Twitter.

Reasons to Gloat If Your Credit Score Is High

People with higher credit scores tend to be less impulsive, better at delaying rewards, and more trustworthy than those with lower scores, according to a study of 63 university students and employees by Shweta Arya, Catherine Eckel, and Colin Wichman of the University of Texas at Dallas; the study included a survey and a set of tasks and games. Thus “it is not too much of a stretch” to say that credit scores might be a useful tool for screening job candidates or potential partners on a dating web site, the authors say. Fair Isaac credit scores are calculated on a scale from 300 to 850, with the U.S. average being 680. In general, a good credit score is anything above 700.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers