Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1501

December 6, 2013

The Customer Support Hierarchy of Needs

Almost five years ago, I was sitting in the conference room of one of the world’s largest insurance companies, trying to push the idea of social customer relationship management to their corporate marketing team. I showed them the power of Twitter and Facebook, and painted pictures of how they could get closer than ever to their customers with these then-new touchpoints.

Roughly 4 hours and 45 slides later, the CMO stood up, shook my hand, and told me how he realized going social and “being there” for his customers was important. And then he added that he just didn’t have the bandwidth for it. He explained why his company was just not ready to go social, and why he believed it would be far too risky to allow his customer service onto public forums or leave his brand open for user generated debate.

About six months later, a tweet from an angry customer went viral and brought the insurance giant’s stock prices down by 8%. In a mere two weeks!

Today, being on social media or providing customers an awesome experience at just about every touch point is not really a choice that businesses have anymore. In fact, delivering exceptional customer experiences is steadily becoming the new status quo. You need to be exceptional today just to keep your head above water.

This begs the question: Why did the CMO turn his back on going social, despite understanding the importance of it? Why didn’t they want to cover every base, be exceptional?

In retrospect, the answer was so simple, so literally basic, I could only hold it against myself.

In 1972, Clayton Alderfer, an American psychologist, proposed the “ERG model” as an improvisation on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Alderfer categorized needs into a simpler continuum. The most basic needs of a person are Existential, which then lead into Relatedness and finally to Growth needs. People do not aspire for a higher level of needs when the lower levels are not met.

If you view a company’s processes and maturity through the lens of Clayton’s ERG model, the insurance CMO’s decision becomes kind of obvious. He simply could not realize the importance of a higher level of support needs, like getting proactive on social media, before the more basic needs of his customer service were met.

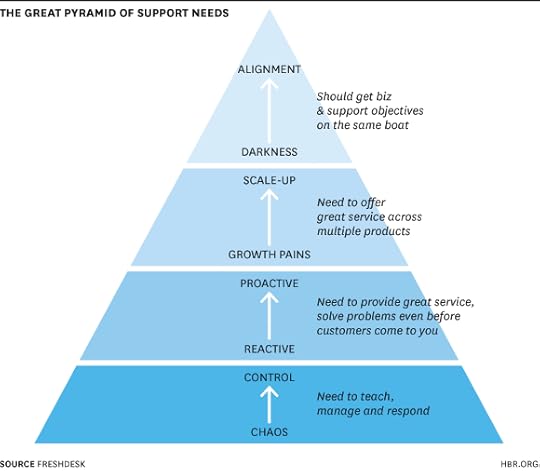

If you looked at how different organizations handled their customer support, the maturity of their operations, and the problems they were trying to solve, companies fall into 4 distinct strata — from a state of chaos, all the way up to the point where their support is perfectly aligned with their business goals. And as you move up the chain towards alignment, the number of companies in each strata steadily falls. I call this the Great Pyramid of Support Needs.

After helping over a hundred startups better focus on their customers, I’ve realized that Freshdesk isn’t really fighting for mindshare against sophisticated ticketing and support workflow tools in this market. We’re fighting against email inboxes and sticky notes. But there is a way up the pyramid — if you’re willing to take the right steps.

Ground Zero: From Chaos to Control. Most small businesses and startups often end up using email to support customers. Even larger businesses are tied with archaic issue tracking tools that do little to streamline support requests. So when the customer base grows and requests get more complicated, things quickly spiral into chaos.

Back then, the insurance giant was struggling to just keep up with their daily conversations, with zero visibility into their support processes. They relied on home-grown scripts from the “dot com” era, and every attempt to move away was struck down with cries of legacy data and sunken costs.

When your business is struggling to make sense of customers in this overbearing and noisy environment, the last thing you’re probably worrying about is adding another channel — no matter how critical it is. So, in a way, what the CMO said back then made sense.

Of course, what he should have done at this point is focus on getting his customer conversations under control. Just publishing a go-to email address, ticketing incoming queries and tracking conversations, could have cut down the confusion. And only then could he have evolved his team to the next stage.

Getting up: Moving from Reactive to Proactive. Luckily, a good chunk of businesses are able to streamline customer queries with the right processes, workflows, and tools. But just reacting to customer issues as they come in is hardly sufficient. This customer experience impact report from RightNow, for example, shows that 89% of customers discontinue transactions when they experience unsatisfactory support. Companies need to anticipate issues and start reaching out proactively to customers — even before the problem crops up.

But most customers wouldn’t hesitate a second to go on some social network to lament in public. Rows of call center agents patiently guiding customers through their scripted responses and canned email responses aren’t going to cut it, when your customers are on so many different channels.

And that’s what keeps many support teams at this stage awake at night — they need to figure out how to move from a reactive to a proactive support process.

It is only when businesses choose to make this transition that they start worrying about bringing in more communication channels between them and their customers. In most cases, their customers have already taken to Twitter and Facebook, so they realize it’s time they went there too.

The Run: Scaling Up and Ensuring Your Support Keeps Up. This is the toughest stage to be in. You have different products and a stellar team supporting in different channels and happy customers. But you’re also growing, and keeping your head over the water only gets tougher from here.

The difference between delivering exceptional experiences to a few dozen customers and continuing that level of service across tens of thousands of customers isn’t trivial. And to do that across channels and different products is a colossal feat. The structures and tools that made sense as a small business do not make sense at scale, and ideologies like “personalized service” start taking the back seat.

And as you acquire customers across geographies, your processes need to adapt to changing time zones and languages. Most companies at this stage start scrambling on their knees to get their support in order because most existing communication structures start to fall flat.

One solution is creating a rich, updated knowledge base like Google’s FAQs that can help streamline support issues by helping customers help themselves.

Successful businesses invest in scalable support channels right from the start. Apple, for instance, uses its wide customer base to its advantage through active user-driven communities. Customers help other customers by answering questions, sharing tips and suggesting workarounds.

As Apple has shown, an engaged community can drive the brand forward, even as the support load gets offloaded between customers. Every customer query becomes a useful resource for hundreds more.

Beyond Support: Aligning the Business with Customers. Quality starts at “conformance” and “zero defects”, and settles at “exceeding expectations.” Very few businesses have reached the peak of the pyramid, when their support structures are perfectly aligned with their business goals and customers. But that is not to say the peak is unattainable. Companies like Zappos have built their entire brand around the customer by obsessively keeping their service quality aligned with the business.

Since companies at this stage already have great processes and tools in place, their biggest threat is having their support representatives lose steam. The relationship between employee satisfaction and productivity is old, established and re-established. Apply that to support agents, the conclusion is obvious — if they aren’t happy, they aren’t about to make any customer happy. And customers can be very unforgiving about these things.

At this level, businesses need to invest on giving support agents more ownership at their jobs, and align business level KPIs like customer satisfaction, response time and accuracy to individual performance through game mechanics, and tangible or intangible rewards.

Solving your customers’ problems is every business’ duty and most do it acceptably well. But then again, most do it acceptably well. At this stage, what makes each support team different is going that extra mile. “Good” is hardly enough — businesses must be doing everything they can to get that “Wow.”

The Brief and Fascinating History of What You’re Wearing and Where It Gets Made

I admit it: The reference to Nixon and kimchi in the headline got me to read it, but this piece on how Bangladesh came to be a world center for apparel manufacturing held my interest. Back in the 1970s, the newly formed country of Bangladesh needed something —anything — to build an economy on, so Bangladeshi businessmen looked to South Korea, which had climbed out of poverty by manufacturing textiles. As people from both countries collaborated to build a textile industry in Bangladesh, most of the culture clash seemed to focus on food: Kimchi made the Bangladeshis vomit, and the South Koreans found the Bangladeshi food repellent. (Nixon's role in the story has to do with global trade limits, which favored Bangladesh once South Korea had hit an export quota.)

The happy ending — there are now more than 4,000 garment factories in Bangladesh — has a cautionary lining, though: A factory collapse that killed more than 1,000 workers this year shows that rapid growth has left many workplaces crowded and unsafe.

On a related note, Planet Money, curious about how T-shirts get made, recently pulled together a fascinating investigation by making its very own T-shirt. You'd better believe that Bangladesh is involved. —Andy O'Connell

Justin Bieber's Involved, of CourseThe Rise and Fall of BlackBerry: An Oral HistoryBusinessweek

For years, every CEO had a BlackBerry. Then, with the introduction of the iPhone, they didn't. While we're all familiar with the decline of Research in Motion, this oral history contains first-hand accounts of RIM's glory days of innovation, followed by inglorious missteps. It's worth remembering the revolutionary idea that started the whole thing: that people — executives in particular — would want to check their email away from the office, a notion that seemed preposterous until BlackBerrys were put into the hands of the likes of Michael Dell, one of the first people to order one. For a time, having a BlackBerry was the ultimate status symbol in business, as well as the ultimate addiction: One former global account manager recalls a CTO referring to the blinking red light as "digital heroin." Then came ill-advised decisions — like making a flip phone when market research showed that no one wanted flip phones — and an accretion of layers of management that operated by consensus. Oh, and an offer from then-up-and-coming star Justin Bieber to rep BlackBerry, an offer that was rebuffed by the marketing department.

"They said, 'This kid is a fad. He’s not going to last,'" recalls former senior business development manager Vincent Washington. "I said at the meeting: 'This kid might outlive RIM.' Everyone laughed."

My Patent Portfolio Is Bigger Than Your Patent PortfolioGoogle's Growing Patent Stockpile MIT Technology Review

Google, which is on pace to collect some 1,800 patents this year, appears to be committed to amassing one of the world's largest patent portfolios. The inventions, Antonio Regalado writes in Technology Review, range from automated cars to balloon-based data networks to images of keypads that can be projected onto a user's hand. Some of them have been filed by the company's founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

Google apparently believes it needs a lot of patents so that other companies will hesitate to sue, lest Google sue back, Regalado says. The company seems to be following the philosophy of Apple, which suffered a $100 million loss in an intellectual-property fight over the iPod in the mid-2000s and now believes in patenting everything. In public, however, Google disparages patent claims. A couple of years ago, when the first major patent lawsuits over smart phones were filed, then-CEO Eric Schmidt criticized certain competitors for relying on legal action out of an inability to "respond through innovations." And the company's top counsel, David Drummond, says a typical smart phone could be covered by as many as a quarter of a million patents, but like most patents they are "largely questionable" and for the most part "dubious." —Andy O'Connell

Too Good to Be True? Fist-Bumping While Rome Burns: The Seduction of Silicon Valley Disruption SalonSalon

First there was the GoldieBlox/Beastie Boys dispute over this terribly clever ad that just happened to result in bit of a legal mess. Then the FDA got all "You can't do that" on 23andme, a home DNA testing start-up that seems to have either ignored or moved too slowly on requests from the federal agency. All this, of course, happened during an almost bacchanal time for Silicon Valley and amid a dismal economy for pretty much everyone else. So Salon staff writer Andrew Leonard felt a little badly when he zipped around in a pink-mustached Uber vehicle to attend a food-networking event centered around making one's own bitters. "This is perhaps the one thing that I didn’t expect from the future: my inability to distinguish it from satire," he writes. But digging into the reasons why the above two controversies happened, Leonard points to how the ethos of the Valley — "Don’t ask permission, move fast, break things" — is finally percolating into everyone's lives: Because we're in a place where (unlike the first dot-com boom) the power of technology is not in its potential but in its reality.

So should we fight it — as is becoming more and more common — or play along? "There are definitely times when I witness the baroque excesses of the Bay Area in 2013… and it all feels like the blind, unconscious decadence of a great empire just before its final descent into madness and irrevocable decline," Leonard writes. "And then I take a breath and wonder if it is still all just getting started."

Take the Money and Run How IBM Bypasses Bureaucratic Purgatory Fortune

If you work at IBM and you have a great idea for an internal IT innovation, you can crowdfund it — with IBM's cash. At most big companies, would-be innovators have to submit their proposals to review boards and then wait months for funding. But at IBM, employees like Ryan Hutton can pitch ideas on the year-old iFundIT site, which is modeled on Kickstarter and is designed to bring out employees’ creativity. Hutton's idea was to build a cloud-based app that would give any employee real-time data about how his or her own apps were being used within IBM. Hutton’s proposal attracted 40 fans on six continents and soon passed the $25,000 threshold at which the company funds a project. Not bad for a 24-year-old who joined IBM straight out of college. —Andy O'Connell

BONUS BITSFamily Matters

You're Interviewing, and Pregnant (LinkedIn)

How Parental Leave Rights Differ Around the World (The Guardian)

Nine-to-Fiver or Workaholic? Either Way, It’s Your Parents’ Fault (Quartz)

Cherry-Pick Profitable Customers by Understanding Adverse Selection

Executives have valuable lessons to learn from the botched rollout of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and not just the fairly obvious point that you want to test your website carefully before you go live. Website functionality problems will pass, but their existence now could contribute to a longer-term and more serious danger to the ACA, a danger that all companies want to avoid.

The difficulties of signing up for insurance on healthcare.gov will deter some people from acquiring insurance. One worry is that people who are sickly, and who know that insurance is very valuable to them, will persevere in signing up while relatively healthy people will be particularly put off by the website hassles. This could tilt the risk pool of insured people towards a higher risk/higher cost group. Known to economists as “adverse selection”, the worst-case scenario is that this could effectively kill the ACA through what is known as a “death spiral.”

Just as bad risks lead to higher prices which lead to worse risks which lead to higher prices and so on in health insurance pools, some businesses have found that servicing high cost customers leads to higher prices, which lead to higher cost customers and so on. These businesses have learned the hard way about product death spirals.

A great example of this was American Airlines’ attempt to lock in its best customers when it introduced the AAirpass in 1981. Price at $250,000, the AAirpass offered unlimited first-class travel on the airline for life. For an additional $150,000, the buyer could bring a companion on any flight she took. To the most frequent of frequent fliers, it turns out that it is not all that hard to run through a few hundred thousand dollars of tickets at first-class prices. So, while the AAirpass purchasers were frequent fliers, they ended up being such frequent fliers that they saved a lot of money relative to paying for each flight. Some AAirpass holders flew so much in one month that buying the tickets would have cost $125,000.

Bob Crandall, American’s CEO for much of the life of the AAirpass, admitted, “We thought originally it would be something that firms would buy for top employees. It soon became apparent that the public was smarter than we were.”

So what did American Airlines do? They raised the AAirpass price. But then only people who used it even more than the original group bought it. The cost of serving the customers went up just as quickly as the price went up because the pool of customers just got more and more expensive. After several price increases topping out at $1 million for an AAirpass, they gave in to the inevitable death spiral and stopped offering the deal.

There’s a more positive side to adverse selection, though, if you can find a way to cherry pick the most profitable customers from competitors that cannot fine-tune their products enough. In fact, this strategy led Capital One’s credit card business to rise from a third-rate player to a market leader.

You may know Capital One as the company with the silly Viking ads. But the story of Capital One, now a huge provider of credit cards and other financial services, began as a lesson in using adverse selection to one’s own advantage. Capital One was founded in 1988, when Richard Fairbank convinced a small regional bank to experiment with its credit card unit. At that time, pretty much all credit cards issued in the United States had the same interest rate on unpaid balances. Annual fees were comparable across cards. Fairbank believed that he could generate higher profits by tailoring the fees and interest rates to the cardholder’s risk of default.

After several unsuccessful experiments, Capital One struck gold (and their competitors were stuck with adverse selection) when it offered the first balance transfer program. Capital One would pay off the person’s credit card debt and charge the new customer little to no interest for the first year (after which interest rates increased to market rate).

One important thing to know about the credit card industry is that the most profitable customers are those who carry balances and do not default. Balance transfers, at least in 1988, appealed to credit card customers who had both of these attributes. A customer would not have a balance to transfer if she did not carry one on her credit card, and wouldn’t bother transferring a balance she did not intend to pay off. As a result, Capital One was able to cherry-pick the most profitable customers from the other cards. Customers who paid their balances in full every month and those who were likely to default did not find Capital One’s balance transfers attractive. But those customers are unprofitable and the other banks were stuck with them — adverse selection at work.

There are probably some entrepreneurial health insurers out there trying to figure out how to cherry pick the good risks who aren’t bothering to sign up for health insurance on healthcare.gov. But the ACA has made that difficult. Rules such as the individual mandate and the fact that insurers cannot base prices on preexisting conditions are meant to specifically deter cherry picking and avoid a death spiral. Most businesses, though, are freer than health insurance companies to learn from the examples set by American Airlines and Capital One. Executives at those businesses can think strategically about how to cherry-pick the most profitable customers and how, at the very least, not to be particularly attractive to the most costly customers.

Four Ways to Scale Digital Capabilities Beyond Your Team

Digital today is part of everyone’s job — and many enterprise organizations are adopting strategic mobile, social, and cloud initiatives to educate and empower employees. But these organizations still face a daunting challenge in distributing digital expertise: how do you develop digital competency more broadly across a large organization?

Here are four ways I’ve seen this problem tackled effectively in my 17 years leading and consulting to digital teams across organizations large and small.

1. Make sure your guidelines align to business objectives

Bringing distributed groups up to speed with digital strategy puts you in the guidelines business. A Center of Excellence model, where an internal unit leads and convenes efforts, can be effective for crafting a digital strategy, driving innovation, and developing guidelines. Examples include: What are the standards for mobile user experience? What platforms are approved or recommended for social media? It’s easy to limit these guidelines to a general digital/mobile/social/video 101 that offers widely applicable, useful advice. But these efforts deliver significantly higher value to the organization when the guidelines are tailored to specific business objectives with tangible examples, like “video of this length performs better for conversion” or “this social content strategy is more effective for sharing to this segment.” General digital literacy programs are important in the enterprise but the bar for a Center of Excellence is higher – this group needs to tie the digital learning to the business benefit.

2. Develop complementary pathways to learning

Consider two paths to learning, with both playing a part in getting digital capability to scale.

The first is on-the-job learning — you have a project that needs resources, and people learn as they go with targeted, just-in-time training to advance the project. Types of new skills might include: shooting low-fi, short-form video; mastering the basics of audio editing; or entering content and metadata into a CMS. Learning this way may well add to the project timeline, but has the benefit of being assimilated “in the field.”

The second is dedicated training. I think of this not only as formal training, whether in-person, conference sessions, or Lynda-style videos, but the kind of focused peer-to-peer training that happens at brown bag lunches or on quiet afternoons. This kind of skill building is ideal when there is an entirely new methodology to be learned, like Agile, or an opportunity to take a skill to at the next level, like honing web analytics through the Google Analytics Academy MOOC.

Think of digital learning as a stairway: The treads are the on-the-job learning, and the risers are the dedicated training that take skills to a next level. The key to remember is that it’s an uneven stairway — on-the-job generally is more immediately practical than the dedicated training but could take longer, and the dedicated training can introduce entirely new skills and systems, but assimilation of skills will vary.

3. Reward digital knowledge sharing, not hoarding

The saying “culture eats strategy for lunch” is never truer than when applied to knowledge sharing. Does your organization actively reward people who are conveners and promoters of digital learning in others? Make your organization more effective by hiring people with the ability to explain the tools, value, and methods of digital strategy to people who otherwise may not use or fully understand them. And find ways to reward those behaviors, like spot bonuses, high profile projects, or formal recognition programs. You can also identify a knowledge sharing goal as a Key Performance Indicator (KPI) of project success, alongside on time and on budget. Ask, “How did people working on this project advance their digital capability?” Finally, remind the entire team that successful enablement is its own reward — the more digital skills are distributed, the more the digital team can focus on higher-value, forward-looking work. Digital leaders must make it clear that the days of the webmaster holding the keys to digital kingdom are long gone, and digital knowledge sharing is a driver of individual and collective success.

4. Clean up your language

It’s easy for many — OK, for me — to become so immersed in and enamored of the technical world that language becomes jargon. Make sure both your presentations and hallway conversations meet a high bar for clarity. Ask third-party listeners with less specialized knowledge to offer frank feedback by email after a talk — my solicited listeners have offered terrific guidance on assumptions or acronyms that can seem off-putting. Expressions like COPE (create once publish everywhere) or native application may be appropriate internal shorthand, but merit explanation. While it’s easy to lapse into jargon, using plain English and being explicit in tying digital’s benefit to the business will help people understand and engage with your content.

Family Businesses Shouldn’t Hunt for Superstar CEOs

It’s a dilemma that faces family businesses all too frequently.

We saw it recently when we worked with a $4 billion global manufacturing business in Hong Kong. The company was managed by the founder, who turned it over to his son when he retired. The two men had created distribution channels, built a supply chain, entered profitable new markets–and, just as importantly, held the family together, ensuring that family members were well taken care of and that family disagreements didn’t harm the business.

Now with the passing of the founder’s son, the third generation–a collection of cousins who are geographically dispersed, prone to disagreements, and lacking the experience necessary to run such a large and complex business–are trying to figure out what to do.

It’s a tough situation, and the third generation decided to look outside the family to find a successor CEO. They wanted someone who could reset the strategy; someone to grow the business again; someone who could broker an agreement between the factions of the family who favor reinvesting for growth versus those who favor high dividends.

They called this idealized new CEO “Mr. Wonderful.”

A worldwide search turned up two leading candidates–both of them superstars. But each person turned down the job. Neither thought the business was ready for a non-family CEO.

These rejections were traumatic, but they have proven to be a tremendous gift. No one could have done everything the third-generation cousins wanted. The candidates most likely to accept such a role would either be incompetent in not understanding the complexity involved (thus dooming the business to failure), or, even worse, they would see an opportunity to assume control and push the family aside.

The situation this family faces is all too common. They approached the problem of succession believing that what worked successfully in the past would work for their generation. It wasn’t until outsiders began rejecting the CEO position that the family realized that even the most wonderful person could not have managed a business that had now grown so complex. Certain systems and structures had to be put in place first. This was work that only the family owners could do.

Businesses don’t need to have billions of dollars in revenue before hitting this point–we see it happen to family companies of various sizes. What should you do if you find yourself in the situation of wanting to bring in an outside CEO? First you’ve got to make some changes yourselves:

Step up as owners. Even if you’re used to your parents running the show, it’s time to realize that you’re the owners now, and have the right–and the responsibility–to develop your identity as owners before an outside executive can come in. Part of the problem is that as members of the next generation, many of you have experienced “learned helplessness.” When, over years or decades, you’ve been shut out of decision making, you may not know how to call the shots, whether the patriarch or matriarch is still living–or not. So your first step is often the most difficult: assume psychological ownership.

Choose your ownership path. Once you’ve taken on the mantle of being owners, then you’ve all got to get on the same page about where the next CEO should drive the business. Know your agenda. Whether your goal is growth, liquidity, a turnaround, or employing more family members, your desired path dramatically affects what kind of person that you’re looking for, and the background and experience needed. The new guy can’t hit the ground running unless you reach a consensus about where you expect the business to go.

Fight the CEO’s fight. Clean up the messes that would hobble the new CEO. If there are family members all over the business that don’t belong there, get them out now. The worst thing that could happen is that Aunt Mary’s son Johnnie is high up in the business, and he’s incompetent. If you leave it to the new CEO to have to remove Johnnie, the leader will lose Aunt Mary’s 15 percent of the vote on the board. That’s a new CEO’s worst nightmare. You will also need to clean up the compensation system. One way patriarchs and matriarchs dominate family business systems for so long is that they buy people off. If someone has a special compensation deal, get rid of it.

Change the power structure. When you have a dominant patriarch or matriarch, the power structure typically gets overly centralized with the strong man or woman in the center sitting on the shareholders’ council, on the board, and running the business. It is impossible to have a successful non-family member CEO succession until this power dynamic changes. Appropriate checks and balances must be put in place. At the very least, you must clearly define and delineate roles for yourselves, the board, and the executive team. One client family reinvigorated their board in order to fill the gaps and correct the blind spots that they knew their CEO had. This strengthened the new guy and convinced the patriarch that it was safe to move aside.

Editor’s Note: Some names, locations, and other identifying details in this post have been changed to protect client confidentiality.

An Economist Finds That Many NFL Players’ Infractions Go Undetected

Officials in the U.S. National Football League detect just 60% of on-field infractions such as holding, according to a mathematical study by economist Carl Kitchens of the University of Mississippi. In analyzing play-by-play data for every regular-season game in the 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 NFL seasons, Kitchens found that being near an official greatly increases a player’s chances of being caught breaking a rule. In conclusion, he says, “there is plenty of reason for coaches to be screaming up and down the sidelines at officials for missed calls that potentially affect the outcome of games.”

Stop Me Before I “Innovate” Again!

The Wall Street Journal is out with a funny (and brutally honest) takedown of a word that has achieved almost-mythical status among business thinkers like me. That word is innovation, and it’s quickly losing whatever meaning it once had.

Journal writer Dennis Berman begins by citing Kellogg CEO John Bryant, the respected head of a well-run company, who was describing one of its “innovations” for 2013. What was the game-changing, head-spinning new offering that Kellogg unveiled? The Gone Nutty! Peanut-butter Pop-Tart. That’s right, a world that has had to survive for decades with Pop-Tart flavors such as strawberry, raspberry, and cinnamon, can now revel in the spirit of innovation that delivered a Pop-Tart with peanut butter.

Somewhere, Henry Ford and Steve Jobs are taking notes.

Now I would never dismiss the virtues of sugary breakfast foods, and it’s hard to argue with the business performance of Kellogg over the last ten years. But if the CEO of a major company can call Gone Nutty! an innovation, then what isn’t an innovation? What does the word even mean anymore? As Berman aptly puts it, “Next time your boss starts droning on about innovation, it might be helpful to stop and analyze: Is she talking about building the next iPod or the next Pop-Tart?”

Words matter — in business and in life. I’ve always found that companies that aspire to do extraordinary things, leaders who aim to challenge the limits of what’s possible in their fields, develop a “vocabulary of competition” that captures the impact they’re trying to have, the difference they’re trying to make, the future they’re hoping to create. Almost none of these companies and leaders use the word “innovation” to describe their strategy — implicitly or explicitly, they understand that it has been sapped of all substance. Instead, they offer rich and vivid descriptions of what they hope to do, where they hope to get, and why it matters.

Robert MacDonald, the most creative and opinionated insurance-industry executives I’ve ever met (yes, I know, he doesn’t have tons of competition), likes to say that the art of doing something new is a matter of “reminiscing about the future.” That is, conjuring up a set of ideas and practices that are so original that established companies can’t begin to make sense of them, let alone respond to them — and painting a vivid picture of what your organization can become if it delivers on its change-the-game agenda. That was the spirit behind LifeUSA, MacDonald’s memorable contribution to an industry whose record of innovation is pretty forgettable, and it’s a spirit shared by most of the genuine innovators from whom I’ve learned.

It’s also a spirit, oddly enough, best captured in a famous tribute to the Grateful Dead rock band. The Dead hold an iconic spot in the history of popular music by virtue of their unique sound, devoted fan base, and ahead-of-its time business model that generated almost all of its revenue from live performances rather than studio records—a model that bands, executives, and academics still learn from today. (One business-school professor actually wrote a book called, Everything I Know about Business I Learned from the Grateful Dead.)

Back when the band was at the height of its powers, Bill Graham, the legendary rock promoter, was asked why the Grateful Dead were so successful. “They’re not just the best at what they do,” he replied matter-of-factly. “They’re the only ones who do what they do.”

I can’t think of a better way to describe the mindset required to do something genuinely creative in business, whether it’s starting a cutting-edge insurance company or developing a truly new-and-better breakfast food, than Bill Graham’s insight about the Grateful Dead. Creativity guru Saul Kaplan, founder of the Business Innovation Factory, warns that too many competitors in too many fields are content with being “share takers”—tweaking at the margins to win a little more business. (That, to me, is what Gone Nutty! Pop-Tarts are all about.) Organizations that do something genuinely creative, he says, are “market makers”—they create a one-of-a-kind presence, a unique offering, unlike what anyone else can do.

That, to me, is what “innovation” is all about, and why the use of the word in everyday business life feels so empty. According to the Journal, Boston Consulting Group polled 1,500 executives about how innovative their companies were, and asked them to rank their organizations on a scale of 1 to 10. More than two-thirds of respondents gave themselves a 7 or higher. Seriously? I guess Ivy League schools are not the only organizations that engage in rampant grade inflation.

Meanwhile, the article continued, in a recent conference call with shareholders, Hewlett-Packard executives described the troubled company’s plans to cut costs, streamline the organization, and rejigger the product portfolio. During the course of the call, they used the word “innovation” 70 times! If there were a Lifetime Achievement Award for Buzzword Bingo, HP would have retired the cup.

So here’s my challenge as we approach the New Year: Why don’t we ban the word “innovation” from the business lexicon for 2014? Let’s force ourselves to be more authentic, more rigorous, more persuasive, as we describe new products, new business models, new solutions to old problems. Now that would be an innovation!

December 5, 2013

Find Your Inner Mandela: A Tribute and Call to Action

Don’t just mourn Nelson Mandela. Learn to be Nelson Mandela.

He was the consummate turnaround leader. As the first democratically-elected president of post-apartheid South Africa, he took on and reversed the destructive symptoms of decline, a larger version of what goes on in any organization or community sliding downhill – suppression of information, group vs. group antagonisms, isolation and self-protection, passivity and hopelessness. He began the turnaround with messages of optimism and hope, new behaviors at the top (he even cut his own salary), and new institutions that created more communication and accountability. He created a new constitution with a participatory process that included everyone. He reached out to former enemies, visiting the widow of a particularly odious apartheid leader for tea. He ensured diversity and inclusion of all groups in his Cabinet. He brought foreign investment back to South Africa and empowered the disenfranchised black majority to take positions in those enterprises.

He knew that he was an icon and shaped a culture for others. His goal was to change behavior, not only laws. The head of what was then Daimler Chrysler South Africa, who had returned to his native South Africa after apartheid ended, motivated a hostile, unproductive black work force by engaging with them in their dream of building a Mercedes for Mandela. This was all about culture, not about financial incentives. People raised their aspirations because Mandela encouraged them.

He also understood the power of forgiveness. Despite 27 years in prison, he emerged with his sense of justice intact — but no discernible bitterness. He maintained his faith in people no matter what, that people would come right in the end, he said. His Truth and Reconciliation Commission was a masterful organizational innovation, permitting people to come forward to admit atrocities and then go forward to make a fresh investment in future improvement. He made the rare transition from revolutionary to statesman. He resisted pressure to simply switch roles from oppressed to oppressor and instead focused everyone on pride in the nation they shared and on working together for larger common goals. His wearing of the colors of the formerly all-white rugby team in South Africa’s 1995 victory over New Zealand was a dramatic healing gesture.

He didn’t cling to power. He empowered. He announced during the election that he would serve only one five-year term – a remarkable action not only in Africa, a continent riddled with corrupt leaders who refuse to cede power, but also for someone who had waited so long and given so much to reach that position. Some observers faulted him for this, because his successors were no Mandela. But he made his point – that many must serve and become leaders, and that a nation is larger than any one person.

He continued to advocate for service after he left office. He asked former U.S. President Bill Clinton to help bring a national service program like AmeriCorps to South Africa. That was the start of City Year South Africa in Johannesburg, featuring young people working in schools to improve outcomes for those who had been left behind. As a City Year trustee, I saw firsthand the positive energy Mandela unleashed.

In a mere five years in office, he couldn’t transform everything. But he could start programs and create institutions that would shift other people’s actions to a more productive path. He could serve as a role model, conveying messages through his personal actions and his words about what kind of behavior, what kind of culture, would characterize the new South Africa he envisioned.

Mandela’s legacy is larger than racial justice and more widespread than his country or continent. His legacy lies in the lessons about leadership he left for all of us. We can pay tribute by channeling him: Discouraged because things don’t break your way? Consider Mandela’s 27 years in prison. Unwilling to give up the perqs of power? Recall Mandela’s no-more-than-five-years promise. Tempted to crush the competition, eviscerate enemies, or publicly humiliate those who make mistakes? Find your inner Mandela, forgive, and move on.

As children, many of us read the powerful, disturbing novel about the evils and tragedies of apartheid in South Africa, Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton. Now the beloved country cries for the death of the leader who ended apartheid. Imagine a Mandela for the Middle East, or multiple Mandelas in the U.S. Congress. There would be more collaboration, more truth and reconciliation, more focus on common goals rather than divisiveness. That would be a gift for the world. The best way to mourn Mandela is to start a movement to transform the culture of leadership, and ourselves.

New York’s Train Derailment is a Reminder of the Importance of Sleep Health Policy

It will take months for the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to examine all the evidence from Sunday’s fatal derailment on New York Metro North line in order to determine its cause. In the meantime, however, the press conferences, the media coverage, the statements by work colleagues and Union officials are giving us a picture that fatigue may have played a central role. One particular reported fact is of interest from the perspective of corporate sleep health policy: the Metro North train driver, William Rockefeller, changed from the afternoon shift to the day shift two weeks ago.

We will have to wait for the NTSB final report, of course, to know if this change was a contributing factor to the derailment. However, we do know that managing these kinds of shift changes with the tools of circadian biology can help avoid negative impacts on occupational performance. For example, we know from research that rotating shifts with the clock is better than rotating shifts against the clock. Mr. Rockefeller’s shift change was against the clock – afternoon shift to day shift rather than afternoon shift to night shift – which is associated with greater sleepiness and more frequent accidents. (Go here for more discussion on the sleep health aspects involved with the Metro North tragedy story.)

Whether or not sleep ends up implicated in this particular tragedy, its role in accidents more generally is beyond dispute, and not limited to railroads or to the transportation industry. Business professor Christopher Barnes reminds us that sleep deprivation was identified as a significant contributing factor in the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl disasters. The Exxon Valdez accident is also widely recognized as an incident in which sleep deprivation played a major contributing role.

In addition to sleep deprivation, diagnosable sleep disorders also impact business directly in terms of lost productivity, accidents, and healthcare costs. Ron Kessler recently reported that the cost of insomnia to the America economy is $63 billion annually. A meta study by McKinsey found that obstructive sleep apnea is responsible for a $65 bil to $165 billion hit annually to the American economy.

As sleep touches everyone, sleep health touches all businesses from the local pizza shop to global financial services. That is why we at the Harvard Medical School Division of Sleep Medicine are reaching out to corporations to collaboratively set standards for corporate sleep health policy. Low cost measures by companies such as requiring healthcare providers to include sleep health questions as part of employee annual physicals can ensure that sleep health is integrated as the third pillar of health and wellness, alongside diet and exercise.

The recognition of sleep’s importance as a matter of corporate policy won’t happen overnight, but it must happen. The result will be happier and more productive workers, more profitable companies, and fewer accidents.

The Mistakes Behind Healthcare.gov Are Probably Lurking in Your Company, Too

Post-launch fiasco, followers of the Healthcare.gov experiment seemed locked in a pointless pattern of irrational expectations, finger pointing, witch-hunts, and spasmodic new deadlines (i.e., more irrational expectations). Fortunately, in the news this week, the situation seems to be turning around (although some are still skeptical). What’s to be learned sorting through the wreckage? The failed launch points to four common mistakes leaders must strive to avoid.

Setting irrational expectations. To expect anything as complex as this particular project to emerge fully functional on day one was the first (and perhaps most important) failure. I’ve seen this mistake numerous times in other industries — from a customer service fiasco by a major telecommunications company that launched DSL at too large a scale to NASA’s failure to recognize the implications of a foam strike in the Columbia shuttle tragedy.

Like these other complex challenges, the more we learn about the process of building Healthcare.gov, the more we understand why the initial launch failed.Communications between the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the hired private IT company, Consultants to Government and Industry (CGI) were tangled and mistrustful, making simple requests for access and information cumbersome and time consuming. The two major players didn’t share priorities: CMS prioritized the October 1st deadline above operability. And the New York Times lists “weak leadership” at Medicare as another complicating factor.

Playing the blame game. The CMS monthly status reports leading up to October 1 (especially the report for August, 2013) reveal increasingly desperate language and blame shifting. Medicare officials, the New York Times reports, “began to suspect that staff members at CGI were intentionally trying to hide flaws in the system to cover up for their inability to meet production deadlines.” CGI staff members express barely concealed frustration with repeated requests for access and with constant heckling emails from CMS staff. Within CMS, Deputy CIO for IT Henry Chao’s group emails employed all caps and direct finger pointing, like this one dated 9/26: “I need Monique to get this in sync…ironed out now — I DO NOT WANT A REPEAT OF WHAT HAPPENED NEAR THE END OF DECEMBER 2005 WHERE MEDICARE.GOV HAD A MELTDOWN (THIS IS TO GET YOUR ATTENTION IF I DIDN’T HAVE IT ALREADY).”

Following old-fashioned buck-stops-here logic, post-failure investigations hoisted mangers like Kathleen Sebelius onto the chopping block, (unsurprisingly) failing to reveal any solutions for Healthcare.gov’s problems. Moreover, it’s simplistic (and just plain wrong) to seek a single culprit. As one computer expert with intimate knowledge of the project told New York Times reporters, “Literally everyone involved was at fault.”

Rolling out instead of cycling out. Healthcare.gov is a good example of the importance of learning small and fast, rather than rolling out a risky new product or service launch all at once. Cycling out in phases includes the expectation of early failures – and demands all hands on deck to learn from them along the way. A roll-out, in contrast, implies that something is all set, ready to go — like a carpet. All it needs is a bit of momentum to propel it forward. For complex initiatives, of course, this is simply not the case. Getting people motivated enough to change is not the real challenge; it’s getting them engaged enough to learn — to become part of a discovery process.

CGI and CMS, like countless organizations under pressure (deadline, bottom-line, or finish-line), employed an organize-to-execute mindset instead of an organize-to-learn mindset, which made it difficult for managers to change their approach, especially in the middle of a crisis. On-the-job learning is necessary to discover and use new answers simultaneously. Managers must make it clear that they understand that excellent performance does not mean not making mistakes — it means learning quickly from mistakes and sharing the lessons widely.

Losing sight of the big picture. Finally, in all of the hoopla over the website, many lost site of the original goal: affordable care for more Americans. For this goal, it seems there is reason for cautious optimism. In spite of the website fiasco, data released by the CMS Office of the Actuary in September, 2013 reveal significantly lowered per capita healthcare expenditures in all three payer categories (a growth rate of 1.3 percent vs. the long-term historical average growth rate of 4.5 percent).

These and other similar trends led columnist/economist Paul Krugman to predict improvements in healthcare spending, in part due to the Affordable Care Act: “The news on health costs is, in short, remarkably good,” he wrote. “You won’t hear much about this good news until and unless the Obamacare website gets fixed. But under the surface, health reform is starting to look like a bigger success than even its most ardent advocates expected.”

The predictable traps described above can be avoided with four leadership actions:

Set compelling, but realistic, expectations. Novel complex initiatives will encounter stumbles and falls along the way to success. Let people know to expect them. They’re an essential part of the learning process! The job is to work closely together to learn fast — and improve faster.

Identify lessons, not culprits. There’s always plenty of blame (i.e., factors contributing to a failure) to go around, and it’s almost always a poor use of time to seek out and punish culprits. Although satisfying to some, it distracts from the core work of learning and improving. Instead of “who did it?” ask, “What happened? What can we learn? What should we try next?”

Design learning cycles. For novel initiatives, design to identify intelligent failures (those that occur in novel territory at a small scale) quickly, then catch and correct them before the next cycle starts. Celebrate intelligent failures as a source of innovation. Recognize that the timeline for completion can be ambitious but it is necessarily uncertain; build in time for recovery.

Emphasize what’s at stake. Reminding people of the big picture helps them understand why it’s worth forging ahead through the trials and tribulations of learning.

Sometimes the best launch is a bit bumpy, a little less glamorous — and certainly more than a little frustrating — but, in the end, the best route to success.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers