Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1502

December 5, 2013

Three Ways to Say No to a Reference Request

Christopher, a seasoned real estate executive, left his job in early 2013 to move to a competitor’s firm. Less than three months later, he received a call from his former boss Theo — in search of a reference letter himself. Christopher was dumbfounded — he had left his former firm precisely because of Theo, a terrible manager whom colleagues found intolerable.

How should Christopher respond? Could he, in good conscience, say yes to providing a letter of reference to someone he didn’t like or respect? Could he say no, and tell Theo off? Christopher listened politely, vacillating between surprise and schadenfrude, racking his brain for a way out of a seemingly no-win situation.

Saying “no” these days isn’t easy. Most of us are terrible at it. There are plenty of people who assure us we’ll be happier if we say no more often. The challenge isn’t entirely philosophical — we know we should say no more often. It’s tactical: how do you actually say no when you’re put on the spot?

If you find yourself in the unenviable position of being asked for a reference letter you have no interest in, or ability to write, there is a way out. In fact, there are three ways out — three excuses that are perfectly suitable. They include:

1. Not being willing or able to spend the time

2. Not knowing someone well enough

3. Not being able to provide a glowing review

Not willing to spend the time. It’s not that you don’t have a little extra time on your hands; it’s that you’re not willing to take the time from what’s important to you — whether it be mission-critical tasks at work or a spending time with your family. Steve Job was famous for saying “no” to 1000 things and using “no” as a strategic business decision. If the ultimate sign of success is an open calendar, think of this “no” as a move towards freeing up your most valuable asset. Play the travel card, the closing a deal card, or the family card — concede that you don’t have the ability to serve as a worthy reference or write an adequate letter of recommendation because it’s takes too much effort away from what you are truly focused on in the moment.

Not knowing someone well enough. The best references come from people who know you, your character, and your work product extremely well. If you’re asked to vouch for someone you don’t know well, the chances of you knocking it out of the park are extremely low. It’s in no one’s best interest for you to spend your political capital endorsing someone you don’t know intimately or can’t speak about genuinely.

So be honest, and decline on behalf of the other person’s best interests: “Medha, I wish I could help, but I really don’t think I know you well enough to provide as strong a reference as you probably need and deserve. I’d encourage you to reach out to someone who knows your work style/product/ethic better. As much as I’d like to help, I think you’ll be better served with someone else.”

Not being able to provide a glowing review. Finally, if you are Christopher and you simply can’t find enough (or any) good things to say about your former boss, it’s in everyone’s best interest to bow out early. Tell Theo that you’d love to help, but you recognize that the letter of reference you’d provide likely wouldn’t reach the level of praise he’s shooting for.

It makes for a tough conversation for sure. But ultimately, it shows that you have Theo’s best interest at heart. The option of saying yes and then badmouthing your boss isn’t really an option — that’s a below the belt tactic you should avoid at all costs.

So take the high road. Have the difficult conversation upfront, but know that your conscience stays intact and Theo’s future job prospects aren’t lampooned by you. It’s one thing to decline endorsing someone; it’s another thing entirely to say yes and then jeopardize their future.

Amazon Turned a Flaw into Gold with Advanced Problem-Solving

“It’s not that I’m so smart, it’s just that I stay with problems longer.”

– Albert Einstein

Several years ago, Amazon was struggling with scaling its e-commerce infrastructure and realizing that many of its internal software projects took too long to implement, a major pain point from a competitive standpoint.

Andy Jassy, acting as a chief of staff for Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, was assigned the task of figuring out why. What he realized was that what many of these teams were building wasn’t scaling beyond their own projects. For each new project, a team would have to reinvent the wheel.

Jassy and Amazon could have come up with a solution to this internal scaling problem and stopped there. But the team went beyond that, figuring that if they were having difficulty with certain technology infrastructure problems, it was highly likely that other companies were experiencing similar problems. Thus, if they could solve these issues for themselves, they could potentially also solve it for others.

So Amazon started to develop an architecture that could be re-employed over and over again by different engineering teams for different projects. These services allowed Amazon the retailer to move more quickly than it had previously.

But the company didn’t stop there, choosing instead to turn its solution into a new business line, offering cloud computing as a service. And so Amazon Web Services was born. Today, AWS generates roughly $3 billion in annual revenue and adds more infrastructure daily than it took to run all of Amazon in 2003 when it was a $5.2 billion retail business with over 7,800 employees.

The lesson of course is that Amazon didn’t stop by solving its problem, but found a “breakthrough solution” that opened up new business opportunities.

Eight Levels of Problem Solving

It’s not easy to create culture that, like Amazon, sees opportunities instead of problems. But it helps to start with a simple motivational framework to focus people on assessing their own problem-solving abilities. Even better is to begin to reward them as you see their problem-solving abilities progress.

What level problem solver can you be?

Level 0 – Can’t see the problem

Level 1 – See the problem and raise it

Level 2 – See the problem and define it clearly (a problem well defined is a problem half-solved)

Level 3 – See the problem, define it clearly, and identify the root cause

Level 4 – Plan ahead to avoid the problem or derivative problems re-occurring (prevention is better than a cure)

Level 5 – Find a practical and viable solution to the problem

Level 6 – Find a breakthrough solution to the problem (for example, one that saves more than it costs, or opens the way to other breakthroughs)

Level 7 – Take initiative to implement the solution or develop the breakthrough

Level 8 – Look beyond problem prevention – create new opportunities from continuous improvement (Think 3M, or the Amazon example above.)

Andy and the team could have stopped at Level 3, but instead, they did an internal assessment of their core competencies, which obviously included retail. But when the company dug deeper, it realized that it also had a competency in running infrastructure, backed by an extremely strong technology team. They were moving up to Level 5. By recognizing that others likely shared their need, they were thinking up to Level 8. The result was a new business opportunity – a breakthrough solution — now worth tens of billions of dollars.

For more, watch my interview with Amazon’s Andy Jassy.

The Best Morale Boost $3 Million Can Buy

The extravaganza takes place in the bathroom. A lady is crooning an ode to the “the only place where I can stay, making faces at my face; a special place where I can stay and cream, and dream.”

A gaggle of gentleman salesmen hang onto every word, erupting in applause.

This song, “My Bathroom,” was composed by Sid Siegel and was just one of the inspirational tunes featured in American-Standard’s 1969 stage and video show “The Bathrooms Are Coming!”

Performed at the company’s “Distributor Principles Conferences” in Las Vegas, the musical, as described by Steve Young and Sport Murphy in their book Everything’s Coming Up Profits, involved both a Greek goddess named Femma being “implored… to start a bathroom revolution” and references to a Cornell professor’s research on water closet ergonomics. (Spoiler: The professor’s work was sponsored by American-Standard.)

“The Bathrooms are Coming!” is one example of an industrial musical, an elaborate Broadway-style show that was commonplace at company conferences in the U.S. between the 1940s and 1970s.

When cost wasn’t an impediment, the performances were sometimes recorded, pressed, and distributed as souvenirs to “recreate the magic and reinforce the message back home,” writes Young. Independently, Young and Murphy began collecting the rare vinyl. I recently spoke with Sport Murphy over the phone.

“You start to think, my god, what were these people thinking?” True. “But the absurdity of these things is kind of like their way of bonding. You know: ‘I spend every day trying to convince people to buy this bathroom suite, and here’s this song that turns it into this big, lush cartoon.’ And they appreciated it because it’s something they could all relate to.”

Industrial musicals weren’t merely about camaraderie and a few chuckles. “There was a lot of minutia that had to be crammed into the shows,” says Murphy. “There were catchphrases that had to be hammered into the head of the employees, just like advertising does to the general public.” Songs were important devices for remembering a product’s key new features, like this one from the 1956 GE appliance show “It’s a Great New Line!”

“Ive Got a Wide Range of Features”

Or for improving sales techniques, per this 1959 gem from the Oldsmobile show “Good News About Olds”:

“Don’t Let a Be-Back Get Away”

They were also intended as a steam valve to acknowledge and dissipate on-the-job stress, like this one from 1961′s Coca-Cola show “The Grip of Leadership”:

And to complain about government policy and interference — a not-so-subtle point made by this number from the 1976 Exxon Convention:

Corporate musicals came to fruition in the wake of World War II, when there was a desire for, as Young writes, “lots of stuff, which American corporations were eager to supply.” The performances also arrived on the heels of story-driven shows like Oklahoma!, which debuted on Broadway in 1943. “It’s a genre that Americans associated with class and with prosperity, so that sort of aesthetic gave it its emotional hook” with big companies, Murphy said.

The U.S. was also feeling pretty darned united. “You’re talking about an entire generation that, between the depression and the war, had gotten into the mindset that we really need each other, we trust our leaders,” he explained. “And the least significant person in the organization is as important as the most prominent one.”

Of course, industrial musicals wouldn’t be an American story without enterprising businessmen looking to boost efficiency and increase profits. According to Murphy, the emergence of music in American corporations can be tenuously traced to National Cash Register at the turn of the 20th century and its founder James H. Patterson, who “had this very paternalistic ideal towards his company.” This ranged from creating more humane conditions for his factory workers and providing extensive training to his sales staff to demanding loyalty and exercising a maniacal sense of control, firing people left and right. Part of his strategy included what Murphy calls “pep talk shows.”

“They would show slides, people would sing songs, and they evolved into theatrical productions that were essentially intended to be morale boosters” while hammering home the company ethos and lauding efficiency in the workplace.

Patterson fired a certain Thomas J. Watson, who later went on the lead IBM for more than 40 years. Watson’s IBM also used music as a central component in company culture, perhaps most famously creating this epic songbook in 1935 that includes “Ever Onward,” the official IBM rally song, as well as odes to senior executives set to well-known tunes (listen to four of them here).

Murphy credits IBM’s use of music as a kickstarter for other companies, particularly those like Mary Kay Cosmetics and Fuller Brush Company that relied on salespeople who needed to stay motivated.

More complicated theatrical wonders like “The Bathrooms Are Coming!” were the achievement of ambitious producer Jam Handy. After swimming in two Olympic games (1904 and 1924), Handy became obsessed with the psychology of employee motivation during his time in the Chicago Tribune’s advertising department, says Murphy. This led to his association with James H. Patterson, who became a mentor.

Handy made a good living producing short films for companies like General Electric, Chevrolet, and Coca Cola in the 1930s, and shifted his focus to making military films during World War II. “After the war” writes Murphy, “the consumer boom opened numerous new opportunities for the company as more and more corporations and agencies sought the Jam Handy magic.” By the 1950s, Jam Handy Productions was “the nation’s largest employer of theatrical talent, producing as many as 20 sales conference shows yearly.” Other production companies followed suit. And as more big corporations started embracing the performances they orchestrated, the industrial musical as written about in Everything’s Coming Up Profits was born.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the whole phenomenon is how much money companies pumped into them. Steve Young notes that the first show composer Hank Beebe orchestrated in 1956, for the next year’s Chevy models, had a budget of $3 million, more than the half to three-quarters of a million that was spent on the average Broadway show during the same time period (the high price was largely due to the fact that the entire production bounced from sales conference to sales conference across the country). All shows weren’t necessarily as expensive, however; this 1955 Milwaukee Journal article covers a $250,000 Oldsmobile show that toured for 10 weeks and featured a storyline involving “an Arabian Nights used elephant dealer.”

Oldsmobile told the Journal almost every car dealer across the country saw the show, spreading a consistent message about new products nationwide. “They had a fine time, saw pretty girls and nice scenery and heard good songs and watched expert dances,” writes the article’s author. “But they also got a pretty strong, impressive sales message.” Indeed, most composers hired by companies had some flexibility in the music, but not in the messages themselves.

And while there isn’t hard ROI data on revenue made based on the content of the shows, according to Murphy it made a strange economic sense to those involved: salesmen were (hopefully) motivated to sell more, while actors, musicians, and composers got paid a union wage. Some, like Fiddler on the Roof co-composer Sheldon Harnick, wound up on Broadway.

Things began to fall apart when both business and popular culture changed dramatically between the 1960s and ’90s. For one, the shows struggled to retain their “cool” factor during the ’60s, often lagging a few years behind trends, and making a bit of a mockery of all things mod or psychedelic. “It would be these guys with very obviously long blonde wigs and granny glasses playing really bad simulations of The Birds,” says Murphy. And why would you stage an elaborate show with fake songs when you could just hire a famous musician to perform instead?

From a 1966 Chrysler Corporation conference, courtesy of Blast Books

From a 1966 Chrysler Corporation conference, courtesy of Blast Books

One can also imagine that the peculiar gender politics of songs like “My Bathroom” were starting to strike the nerves of an increasingly diverse workforce as time inched closer to the turn of the century and sales conferences weren’t merely boys clubs. (Though Mary Kay slowly developed its own quasi-religious conferences, complete with songs, by the 1980s.)

But perhaps the biggest reason industrial musicals crawled into historical oblivion has to do with a change in the employer-employee relationship (not to mention the place of the U.S. economy in the country’s culture).

“It was likely a chicken-or-egg situation,” Murphy theorizes. “The shows probably motivated people, but it was also coming from a corporate culture that felt a sense of belonging. In the bigger corporations, they had a real stake in keeping their employees happy and loyal. They would rather have a lifetime employee who really understood the business and believed in it, rather than a series of revolving door specialists who would come and go.”

In a letter Hank Beebe wrote to Murphy and Young upon the publication of their book, he remarked that the text brought to life “that [era's] civilization — its extravagance, its confidence, its belief that the future belonged to those who reached for it. Even the belief in the corporation as a force for good comes through, a belief that recent history has not exactly upheld.”

Whether or not you buy into this nostalgia, Thomas J. Watson’s lyrical approach would probably be lost on the IBM of today. As the Washington Post reports, Watson once listed the company’s values in the following order: respect for the employee; a commitment to customer service; and achieving excellence. By 1994, when Louis V. Gerstner Jr. headed the company, he orchestrated an epic turnaround, putting shareholder value and customer satisfaction at the top of the list. Employees and community were at the bottom. The most recent two CEOs placed investor returns at the top of their priority lists.

But I’m sure there’s a song for that somewhere.

Small Businesses Need Big Data, Too

If you run a small or medium-size business, chances are you haven’t felt a need to invest in extensive customer data, relying instead on your well-honed intuition to help you hold your own against data-rich, bigger competitors. A lot of small-firm owners and managers feel that way, and in many cases they’re justifiably proud of their competitive intangibles—a gut sense of the market and the flexibility to change quickly.

What you may not realize is that investing in data and learning how to use it might be transformative for your business. In research we conducted with Gillian Armstrong of the University of Ulster and Andrew Fearne of the University of Kent, we found not only that small businesses benefited from the precision offered by customer data, but also that exposure to data encouraged owner-managers to share insights with employees and get them involved in companies’ competitive thinking.

Of course, for the smallest businesses, access to extensive consumer data can be prohibitively expensive, a point we’ll address in detail in a subsequent post. But cost isn’t the only barrier. Small firms tend to find the whole concept daunting—they know they lack the expertise and the time resources to make good use of the information. Our three-year project was designed to build awareness among small firms about the value that data could have for their businesses.

Funding from a regional UK government agency enabled us to get over the cost barrier: It allowed us to provide loyalty-card information from supermarket giant Tesco, free of charge, to seven firms in the Northern Ireland region of the UK. These companies, ranging in size from seven to 45 employees, sell such things as dairy products, baked goods, vegetables, and desserts to Tesco and another grocery chain, Sainsbury’s (we tasted some pretty amazing soups during the course of our research—a tough job, but someone has to do it).

The data, provided by analytics firm dunnhumby, covered such things as consumer life stage and lifestyle, market-basket analysis, and best-performing stores for the small firms’ products.

The formalized structure of loyalty-card data within a statistical format requires firms to take a more formalized and structured approach to marketing planning—that’s a challenge for small companies. Owner-managers were encouraged to attend workshops, and one of us (Christina Donnelly), after being trained by dunnhumby, worked one-to-one with owners and managers to help them retrieve the most relevant data from the loyalty-card database and analyze the information, so that the companies could answer questions such as “How is my category performing?” “What is the most popular flavor of bread?” “What type of consumer buys a product similar to mine?”

We found that prior to being exposed to the loyalty-card data, the small businesses tended to be dominated by their owner-managers, who made decisions on the basis of their past experiences and any consumer information they could get their hands on. For example, one firm, having been asked by a retailer to produce a range of ready meals, simply looked at other products on the market and tried to imitate them. In other cases, the small firms followed guidelines laid down by the big retail buyers.

Once they were given access to loyalty-card data, most of the small firms took to it immediately. They were quick to adopt a more formalized approach to marketing planning. They were able to envision long-range innovations, rather than reacting to competitors’ or the retailers’ actions. One small-firm owner said the data had changed the company’s ideas about how to grow its consumer base. Another said, “Now we know precisely who our target consumer is.”

A yogurt maker, for example, learned by analyzing the data that older adults were a key market for its products, so when the company’s representatives visited supermarkets for in-store tastings, they no longer tried to entice younger shoppers and instead focused on older people. The tactic improved the events’ productivity.

But the small firms didn’t abandon their reliance on experience. Instead, the data complemented the owners’ and managers’ intuition, giving them new confidence.

Moreover, the data amplified the firms’ inherent entrepreneurial nature. Workplaces became more collegial: Most of the owner-managers shared the card information with their firms and encouraged employees to get involved and offer new ideas.

Big Data threatens to create a deep divide between the have-datas and the have-no-datas, with big corporations gaining advantage by crunching the numbers and small firms left to stumble in the dark. The small firms we worked with were well aware that they were at a severe disadvantage to big competitors that had the financial muscle to buy into loyalty-card data and the resources to use it.

Governments and universities can play important roles in bridging the divide, providing funds and expertise so that small firms can get access to, and learn to interpret, data. Our project is an example of a fruitful collaboration—among the University of Kent, the University of Ulster, dunnhumby, and the government funding body. The quality of the learning is important. A key reason why this project worked was the one-to-one help for the owner-managers. Data is only as good as the people who use it.

For small and medium-size firms that do manage to acquire consumer data, there’s still more work to be done: They need to be sure to encourage employees to participate in thinking about how to use the information competitively. We saw firsthand that inclusivity energizes firms, driving innovation.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

Are You Ready for a Chief Data Officer?

Does Your Company Actually Need Data Visualization?

Nate Silver on Finding a Mentor, Teaching Yourself Statistics, and Not Settling in Your Career

Stop Assuming Your Data Will Bring You Riches

How to Manage Impossible Clients

If you provide some kind of service to clients (as most of us do), you’ll know from experience that some of your beloved masters are easier to work with than others. Some are delightful, some forgettable, and a few you proclaim as downright impossible. Although your view of the client depends on a multitude of factors (such as your relative levels of experience, your disciplines, and the nature of the project), I will go out on a limb to say that there really is such a thing as an “impossible” client — someone who exhibits one or more “bad behaviors” that make the collaboration more difficult than it needs to be and frustrates your ability to perform the service you have been engaged to provide. For many of us, when clients act this way, our primal instincts kick in and we’re tempted to respond with even worse behaviors of our own.

There is a better way. Impossible clients can, in fact, be managed; but only if you resist the temptation to fight fire with fire. Instead, deliver — and let your talent speak for itself. If you fulfill your end of the bargain, it’s much easier to find positive outcomes when clients behave badly.

Here are four typical “impossible” behaviors, and ways of responding that I have found effective:

Impossible Behavior #1: Self-Barking (aka Micromanaging)

I worked in the United Kingdom for a couple of years, and there learned a favorite client-related expression: “You don’t hire a dog and bark yourself.” Unfortunately, that’s exactly what some clients do — insert themselves where unneeded, micromanage, sometimes even perform the work they hired you to do.

Temptation: Take offense. Start a pissing contest of competence display. Out-perform your client to demonstrate your superior abilities.

Better plan: Continue to do your work, unfazed. Wait for your (eventually desperate) client to ask for help when the going gets rough. Let your skill and talent speak for themselves.

If you are better at your job than your client (you are, right?), you can be content in doing your work, and then laugh and privately roll your eyes when your client inevitably says something like, “Well, I had to get the ball rolling…”

Impossible Behavior #2: Feedback Deluge/Drought

Either your client inundates you with feedback — I once developed a book with five authors and received a marked-up manuscript from each — or starves you and leaves you blindly wandering down a potentially wayward path.

Temptation: In the case of deluge, complain that you can’t possibly be mindful of so much criticism. In the case of drought, demand more input and refuse to continue until you get it.

Better plan: When deluged, negotiate a process in which the client’s feedback (no matter the amount) is pre-synthesized and delivered in digestible chunks, so as to be (or at least appear to be) more manageable. In the case of drought, don’t make any assumptions. Ask for feedback directly, early, and often.

You may not always be pleased with (or agree with) the feedback you hear — especially when you’re hearing too much of it or none at all. But keep in mind that your mission is to collaborate, and that your goal is not to train your client, but to do the best possible work you can. Feedback implies a discussion and a back-and-forth, and will always improve the outcome.

Impossible Behavior #3: Deadline Dichotomy

Impossible clients are careless about deadlines — they don’t necessarily deliver the materials you need on the agreed upon schedule (thereby delaying your process and disrupting the cadence of your work), but no matter how laggardly they may be, your deadlines do not budge. If you miss a milestone, the client hangs a millstone around your neck.

Temptation: Whine. Accuse the client of foot-dragging and being unreasonable. Plead/negotiate/demand more time.

Better plan: Create a realistic timeline to start. Overestimate how long it will take you to complete a task by a factor of two. Work late or on weekends when you have to.

I don’t let clients know exactly how long it takes me to do what I do. This is not to deceive them, but because my pace is born of decades of practice, and the amount of time spent is not equivalent to the amount of value delivered. (I realize this differs from profession to profession.) We once tried to develop a fast-track approach to the development of book proposals and found that, on average, it took twice as long as the standard process. Why? We were so focused on the deadlines we couldn’t focus on the work itself.

Impossible Behavior #4: Credit Grabbing/Blame Assigning

When the project is completed successfully, the impossible client takes credit for it and downplays your role. If the work falls short, the client makes sure you and your firm are prominently mentioned.

Temptation: When things go well, thrust yourself forward. Seek credit. When things go wrong, fade back. Place blame. Tell the “real story” behind your client’s back.

Better plan: Compose a written agreement that specifies exactly how you/your work will be acknowledged in public materials. Or, decide to keep a low profile, even remain anonymous. Let the work speak for itself. Let the client shine.

Everyone wants recognition for the work they do, but your main task is to fulfill your promise. If you do that, the chances are better (although not 100%) that the client will speak well of the work and of you, and that word will get around. Recognition is warming. More work keeps the heat on.

A final thought. In the study of resilience, there is an argument that holds that disruption and difficulty can bring positive outcomes and new opportunities. I have found this to be the case with impossible clients. They are, of course, not really impossible at all: just difficult, trying, exasperating perhaps. But in every engagement I’ve had with an impossible client, I have found or developed better ways to collaborate, communicate, and to bring impossibility back into the realm of the possible.

Would You Rather Have Brazil’s Economic Problems or America’s?

It’s been a great millennium for Brazil, so far. The country’s economy has boomed, wages have risen sharply, and joblessness has fallen to levels that economists deem pretty close to “full employment.” Government policymakers have kept deficits relatively low and inflation in check — at least by Brazil’s historical standards. And the World Cup and Olympics are coming! Yay!

But there’s trouble ahead — and not just because Brazil may not be entirely ready to host the World Cup and Olympics. Two of the main drivers of a country’s economic growth are the size of its workforce and the productivity of its workers. In Brazil, rapid growth in the working-age population and rising labor-force participation have been boosting GDP for years, but have now pretty much run their course. The country’s fertility rate has fallen from 4.1 births per woman in 1980 to 1.8 now, and that decline has meant fewer people entering their working years. And full employment means that labor force participation simply can’t go much higher.

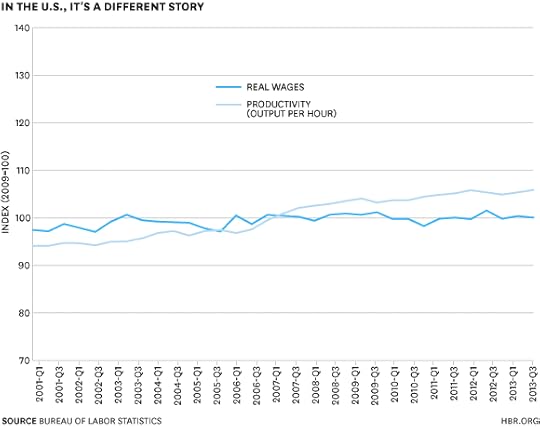

I heard these arguments from Marcelo Carvalho, BNP Paribas’ chief economist for Latin America, earlier this fall in São Paulo. He was speaking at an HBR Brasil conference on Brazilian competitiveness, and his message was pretty gloomy. The country’s only hope of continued economic success, he said, was strong productivity growth. But it hasn’t been getting that lately. To illustrate, Carvalho showed a variation of the chart below:

His message was that Brazilian workers have been getting a gift that can’t just keep on giving. My reaction, though, was that the chart looked awfully familiar, in an upside-down sort of way. As in, Isn’t this the exact opposite of what a chart of productivity and wages would show in the U.S.?

Sure enough, it more or less is. The lines are flatter in the U.S., as befits an already very developed, very rich economy. But in sharp contrast to the situation in Brazil, productivity has been rising faster than wages in the U.S. since 2001 — which lends a helpful perspective to the often downbeat discussion over the economic future here:

In fact, productivity growth has been outstripping wage growth in the U.S. for decades. Some of the gap has to do with our ever-costlier health-care system: Overall worker compensation has risen faster than wages, with health-insurance bills making up much of the difference. But labor has also lost ground to capital in divvying up national income. Millions of people have been dropping out of the labor force. And rising income inequality has been keeping productivity gains out of the hands of the typical worker.

So down in Brazil, productivity growth is economic problem No. 1. Up here, it’s not — or at least hasn’t been for the past 15-20 years, since the Great Productivity Slowdown of the 1970s and 1980s gave way to a modest but very real productivity boom. Productivity growth will be a problem if it stops, and every time it slows for a few quarters there are those who proclaim that the productivity dividend from the rise of computers and the Internet has already been paid out. I can’t shake the feeling, though, that we’re still in the very early stages of the digital reordering of everything. And the U.S. economy seems to be taking greater advantage of that reordering than any other, with the U.S. investing more intensively in IT than any other country, and U.S.-based companies at the forefront of most interesting digital developments.

I’m told that all articles on productivity must at some point recite economist Paul Krugman’s line from his 1990 book The Age of Diminished Expectations:

Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.

At the most basic level, then, the U.S. economy has been delivering the goods to raise living standards. It just hasn’t been delivering them to all the right addresses, instead funneling the productivity windfall into fortunes for a few and a lot of medical spending of dubious value. The former may or may not be a necessary accompaniment to economic disruption and growth; the latter definitely seems like a silly waste. What they have in common is that their solutions are at least as much political as economic. That doesn’t mean they’re easy solutions — if Eric Brynjolfsson and Andy McAfee are right and we’re all about to be replaced by machines, the political challenges will mount even as productivity skyrockets. But it still seems like it’s a much better position to be in than not having any productivity growth at all.

Back in Brazil, where productivity stopped rising in 2008, there doesn’t seem to be any simple prescription for getting things moving again. Carvalho talked about increasing investment (investment’s share of GDP is lower in Brazil than any other major Latin American economy), which would surely help. But productivity growth also comes from other, harder-to-pin-down sources — technology, government regulation, management techniques, education, societal norms. It’s the most important determinant of living standards, yet it’s really hard to manufacture on demand.

Reduce Stress with Mindfulness

Maria Gonzalez, author of Mindful Leadership, explains how to minimize stress – not just manage it. Contains a brief guided breathing exercise.

December 4, 2013

How to Argue Across Cultures

Do you tackle problems with colleagues, partners, and customers head-on? If so, chances are you’re from Western Europe or North America and, our research suggests, vulnerable to blind spots when working with people from other parts of the world. And if you’re from an East Asian culture, the subtle cues you rely on to signal your disagreement may be sailing right past Westerners.

In much of the West, it is considered maddeningly inefficient to talk around an issue, whereas East Asians tend to view direct confrontation as immature and unnecessary. That difference amounts to a frustrating cultural divide in how people solve problems at work.

Westerners prefer to get issues out in the open, stating the problem and how they’d like to see it resolved. People don’t expect their logically constructed arguments to be taken personally. Often, they describe problems as violations of rights and hold one another accountable for fixing them. In fact, they consider such behavior “professional.” But that same approach is an anathema throughout East Asia, where the overriding impulse is to work behind the scenes through third parties to resolve conflicts, all the while maintaining harmony and preserving relationships. When there is no third party to intervene, the professional approach to confrontation is to subtly draw attention to concerns through stories or metaphors, placing the onus on the other person or group to recognize the problem and decide how to respond. To convey disapproval, an East Asian might say, “That could be difficult,” without explaining why.

Why It’s Hard to Meet in the Middle

Although common sense tells us we should move past our own cultural preferences in a global business environment, it’s not easy to do. And many people don’t realize how pronounced the cultural differences are until they find themselves perplexed by a colleague’s behavior.

Recently, a Western manager spoke to us about the mysterious (to him) behavior of a high-potential East Asian he had been assigned to mentor during a three-month assignment at the company’s U.S. headquarters. He said, “Every time the East Asian manager disagrees with an American marketing manager he’s working with on a project, he comes to me to resolve the disagreement! Is he doing this because the marketing manager is a woman?” Gender probably has nothing to do with it, we explained. More likely, the East Asian manager worries that direct disagreement will damage their working relationship, so he’s involving a higher-level manager to preserve peace by adjudicating.

In avoiding direct confrontation, East Asians can appear to Westerners as unresponsive or even passive-aggressive. At the same time, Westerners who confront directly may come across to East Asians as aggressive and disruptive to traditional status hierarchies. And neither side recognizes its unintentional affront to the business relationship. The result of all this? Discord that could have been resolved escalates into a major conflict in which everyone stands to lose: Deals and long-term business relationships fall apart. Take, for instance, the now-defunct joint venture between French-owned Danone and Chinese owned Wahaha. Based on the results of an internal audit, majority owner Danone publicly accused the head of Wahaha—and his family— of siphoning off $100 million from the JV. That direct confrontation was followed by an epic corporate battle that ended, after years of public and legal fights, with the dissolution of the joint venture.

Here’s an example with a much better outcome: A Western entrepreneur had a contract to supply a German buyer with bicycles that he was having produced in China. When the bicycles were ready for shipment, he went to the plant to check on quality and discovered that they rattled. Rather than telling the plant manager that the rattling had to be fixed before shipment, he suggested that they take a couple of bikes off the line and go for a ride in the countryside. At the end of the ride, he mentioned that he thought his bike had rattled; then he left the plant and anxiously awaited news from the German buyer. Had he relied on his own cultural preferences, he would have told the plant manager up front that the rattling bikes had to be fixed before shipping. But because he was attuned to East-West variation in approaches to conflict, he knew that a direct confrontation could cause loss of face and retaliation might very well result in a shipment of rattling bikes. The plant manager apparently picked up on the entrepreneur’s culturally sensitive cues and assumed ownership of the problem, because the German buyer received a satisfactory shipment of bikes.

Adapting Your Style

The most effective global managers, like the entrepreneur in the bike story, develop the focus and control to shift from one style of confrontation to the other, depending on the situation. If you have little experience managing conflict beyond your cultural comfort zone, here are some suggestions for adjusting your style.

If you’re most familiar with the West:

Look for subtext. If you suddenly realize you’re listening to a story or a metaphor, that’s a signal. Think: Why this story? Why this metaphor? If you’re stumped, you might say, “How interesting. Why do you think the person in the story did that? What was she expecting others to do?”

Suggest a tentative solution. Express it as a question—“Could this be done?”—and not as a given. Listen for “that might be difficult” or a noncommittal “yes,” which may really mean “no” and certainly suggests that your approach isn’t optimal.

Don’t be put off by third-party intervention. Understand that by not confronting you directly, your East Asian colleague is treating you with respect, even while disagreeing with your approach.

If you’re most familiar with the East:

Brace yourself for direct behavior. When your Western counterpart directly challenges your assumptions, offers solutions, or asks you to take responsibility, it is unlikely to be an intentional attack on you. He is probably not questioning your status or authority, but rather questioning the situation. You’ll reduce the risk of losing face by arranging for a private meeting to discuss issues.

Ask follow-up questions to test for understanding. What seems clear to you may be lost on those more familiar with Western communication styles—even when spoken in their language.

Recognize that your counterpart will be surprised and possibly offended if you communicate your concerns through a third party rather than directly.

Of course, you don’t have to make all the concessions yourself. But you’ll need to make some if you want to resolve more cross-cultural conflicts than you create.

Ten Essential Tips for Hiring Your Next CEO

Selecting a new chief executive is critical because so much rides on a positive outcome. Is this the right person to lead the company in this particular business, at this particular time? Will he or she collaborate with the board, or fight it? Is there a process in place for cultivating, identifying, and appointing not just this CEO, but the one after that? From directors, executives, and specialists whom we have witnessed, worked with, and interviewed, and from our own search and consulting experience, we draw ten principles for executives and directors to guide the executive-succession process.

1. Remember that people set strategy. American baseball legend Yogi Berra warned, “If you don’t know where you’re going, you might not get there.” Berra was famous for his “Yogi-isms,” but this one contained an essential truth: inchoate strategies and ineffectual leadership generally go hand in hand. Conversely, directors and executives who know where the company should be going will be best equipped to guide it there.

2. Implement an evaluation methodology. Use an evaluation system that links the company’s strategic requirements with the prospects’ individual capacities and performance, with the latter focusing on their integrity and ethics, team building, execution excellence, shareholder return, and personal gravitas—and ability to work in the boardroom.

3. Include in the current CEO’s evaluation an assessment of how well the company is building a succession plan for the next generation of company leaders. When we asked the chief human resources officers at a number of major companies whether they had a coherent system in place to evaluate and compensate the CEO’s succession performance, most reported that their firm had none. And even those who did said that the reward system was still too weak to effectively guide the CEO’s actions. Do this now.

4. Place the board leader in charge. By tackling the job in partnership with a still-effective chief executive, the board leader can help root the process deeply in the company’s management development, preventing succession from becoming an event-driven crisis. It is also helpful to consider both short-term disaster scenarios—are one or two lieutenants ready now to replace the chief executive if an accident or illness suddenly disabled the top executive?— and long-term outcomes—will a handful of executives be ready candidates to replace the CEO after a planned exit five years in the future?

5. Retain a high-performing chief executive, but also work to keep capable successors. Able executives who have learned how to run an enterprise are likely to be itching for a CEO opportunity. Effective succession requires offering incentives to these potential chief executives—including extra compensation—to retain their presence as CEOs-in-waiting if a well-performing chief executive still has ample energy in the battery.

6. Seek candid comparative data on inside CEO candidates from those who had worked with all of them. GlaxoSmithKline’s 450-degree assessment, which confidentially vetted the views of all company executives who had worked with the three final candidates, is a useful illustration of this data-seeking process. Administered by either a trusted insider or a third party, the 450 yields comparative data on finalists, all of whom are obviously very strong leaders in their own right. Using such data sometimes yields surprising results. At GSK, the dark horse emerged as the best choice by a wide margin once the additional comparative data was compiled.

7. Make direct contact with both sources and candidates to verify information. Even when engaging a third party, boards cannot fully hand off the vetting process. Directors will want to personally check on referencing. A few trusted sources can yield far more useful data than a large number of less certain sources. In the absence of a trusted relationship, references can sometimes reveal limited inside information and even false information. As an example, one source claimed that a top candidate was an alcoholic, but when further vetting with more trusted sources confirmed no such behavior, the company chose the falsely accused candidate as its chief executive.

8. Review outside consultants carefully to prevent conflicts of interest. Intentionally or not, executive search consultants hired to help with a CEO search can sometimes offer an overly affirmative view of a candidate they have sourced or an overly skeptical view of one they have not had a hand in finding. In one instance, a board’s external search led directors to identify an executive at a Fortune 100 company who was ready to accept the job. As a final step in the process, the board retained an outside consultant to make one last evaluation of the candidate that the board had identified. The consultant, however, reported a serious defect in the candidate and urged against the executive’s appointment. When the board then turned to one of us, we found no evidence of the alleged shortcoming and recommended the executive’s appointment. We also found reason to believe that the first consultant had hoped for a new CEO search assignment if the candidate he opposed was rejected. The company finally went with its initial preference, and the new chief executive performed exceptionally well over the next five years.

9. Maintain confidentiality. We have seen stellar CEO candidates drop out of consideration when their identity is inadvertently revealed, especially if they are serving as a chief executive elsewhere. Journalists inevitably circle during a high-profile external search, and communicating orally and avoiding media contact can help preserve confidentially. One way to prevent a damaging revelation is to ask outside references for guidance on a candidate not for a CEO position but rather for a board seat. Now that boards increasingly partner to lead the enterprise, not just monitor management, many of the same leadership qualities that make for an effective director also make an effective chief executive. Thus, board-seat evaluations can provide a veiled but useful appraisal of CEO-related competencies.

10. Embed succession planning in corporate culture. Creating a culture entails many steps, including performance incentives for executives to build the system, a development capability that repeatedly reaches large numbers of managers, coaching and mentoring by both directors and executives, and an openness to both inside and outside candidates. Above all, it requires an active partnering between the directors and the chief executive to preemptively ensure that their pipeline is full and its occupants are developing in the upward direction.

When determining suitability to be CEO, companies will want to remind themselves of an obvious premise: No candidate is perfect. The goal is to understand the relative trade-offs among the candidates’ strengths and weaknesses, and to ensure that the prospects’ deficits are not in areas that are especially critical for company performance. The fate of the enterprise depends upon it.

Ram Charan, Dennis Carey, and Michael Useem are co-authors of the book Boards That Lead: When to Take Charge, When to Partner, and When to Stay Out of the Way, (HBR Press 2014).

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

Hiring and Big Data: Those Who Could Be Left Behind

How to Use Psychometric Testing in Hiring

A Fairer Way to Make Hiring and Promotion Decisions

Why HR Needs to Stop Passing Over the Long-Term Unemployed

How Black Friday Lost its Mojo

Black Friday 2013 turned out to be, well, a bit more like a Grey Friday. The National Retail Federation estimates that consumers spent $57.4B over the four-day Thanksgiving holiday weekend, a 2.7% drop from last year’s $59.1B shopping spree. This slide in sales is causing anxiety about the economic recovery possibly sputtering.

But retailers should forget about drawing conclusions based on Black Friday purchases. As a sales event and barometer of consumers’ fiscal health, this former indicator of holiday sales is losing relevance.

Last weekend’s sales drop shouldn’t be shocking –customers are simply shifting more shopping to the web. This results in a substitution effect: fewer sales on Black Friday and more on Cyber Monday. In contrast with the tepid Thanksgiving weekend brick-and-mortar numbers, IBM estimates that sales on Cyber Monday jumped by 21%. It’s not a big stretch to predict that buying on Cyber Monday will increase next year too, again at the expense of Black Friday.

While the rising popularity of Cyber Monday is one reason for Black Friday’s poor showing this year, another reason can be squarely laid on the doorsteps of brick-and-mortar stores themselves. They made the mistake of thinking that more was the same as better. This year, with Thanksgiving being so late on the calendar, U.S. stores started their “Black Friday” sales days or even weeks ahead of the actual Black Friday Some, such as Hugo Boss, hosted brief “private sales” claiming to offer the same discounts that would be available on Black Friday. Why fight the crowds if the same discounts can be garnered a few weeks earlier? These early sales caused yet another substitution effect – they siphoned off Black Friday purchases.

I’m reminded of some close friends of mine who host an annual, no-holds barred summer party. It’s a great party and because of its success, this year they decided to make it a three-day celebration. The idea sounded great in theory (more party! More friends! More food!) but it didn’t work out well in practice. While everyone was happy to see each other on Day 1, we all held back because we knew there were two more days to enjoy. Then by the time Day 3 rolled around, everyone was just tired. Spreading out the fun over three days had not resulted in more net fun — just fun diluted.

Similarly, retailers’ extended sales have dimmed the excitement of shopping on Black Friday – the chum that used to incite buying frenzies at malls. It’s hard to get jazzed about the Black Friday sale of “30% off everything in the store” at Ralph Lauren Outlet stores, for instance, when that sale had already been running for at least a week. This ho-hum shopping experience ushered customers home from the mall early.

But does it matter if Black Friday fades if the shopping season gets peanut-buttered around over several other days? I think it does. One side effect of all of this discount jockeying is that customers lose a call to action. In past years, shoppers could be confident that Black Friday deals were likely to be the best of the season. But this isn’t the case anymore. Dire discounts and once-taboo discussions over how early to open on Thanksgiving revealed that retailers are hungry. Rather than marking the starting point of the shopping season and the best deals of the year, this year Black Friday marked a “meh” sort of midpoint to a season that many consumers believe will yield better discounts by year-end.

Will retailers change their ways after learning this year that more is not better? Probably not. Retailers are now stuck in a discounting prisoner’s dilemma. It’s in the best interests of retailers to return to the practice of making Black Friday weekend a once a year blow-out event that provides the best discounts and generates purchase-propelling excitement. However, each retailer also has an incentive to “cheat” by offering discounts in advance. As a result, while Black Friday weekend will always be an important sales weekend for retailers, its mojo is fading.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers