Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1500

December 9, 2013

Dan Ariely on 23andMe and the Burden of Knowledge

News broke Friday that 23andMe, the provider of genetic testing services built around a $99 kit you can use at home, would cease providing health information to consumers while the product underwent a Food and Drug Administration approval process, because the FDA considers the test a medical device that requires regulatory review. While the FDA reviews the product, 23andMe will continue to provide customers ancestry data and raw data.

Coincidentally, right when the news was posted, I was speaking with celebrated behavioral economist Dan Ariely about 23andMe. Ariely saw an ad for the kit and his curiosity prompted him to take the test. When he got the results, he knew he wanted to direct a researcher’s lens on it, because “this was standard, classic, even an exaggerated case of information overload. I wanted to analyze it from the point of view of what we can do with this information, and what should we do. I also had the thought, maybe we could use it for our research on decision making.” So Ariely got kits for all of the researchers on his staff. He spoke to me about the results of that experiment, and how he hopes products like 23andMe could improve based on behavioral science.

What was it about the results that made you think that the 23andMe service warranted more attention?

So I got all these results about my future health and illness, and didn’t know how to digest them. It was overwhelming, and not necessarily useful information. I was also anxious about it. I found myself wondering how my kids were doing. So I also got kits for my family. And then I also got the kits for everyone in my lab.

What was the reaction to the kits in the lab?

One person did not take the test, because she didn’t want to know. Most of the other researchers reacted negatively to the information they received. And in particular they didn’t like that the system did not help you separate things you could do something about from those you couldn’t. If, for example, I know that I might have a chance of high cholesterol, maybe there’s something I can do about it. On the other hand, if I’m likely to have colon cancer, I don’t know what I can do about that. After the initial trial, as far as I know, no one from my research lab went back to the website to get more information. Curiosity drove the initial use, but there wasn’t much interest afterward.

So it was dissatisfaction with the presentation of results.

It was more than that. People were sort of frightened, and we’re a lab of people who work on decision making. On the other hand, they highly valued the family finder aspect — where do you fall on the family tree and what’s your ancestry and who you’re related to. For me it was great to realize my kids were 99.7% mine [LAUGHS].

You said people were sort of frightened. Do you think 23andMe is scaring people to sell their product?

No. But I do think it relates to what psychologists call the burden of choice. If a doctor tells you that you have to make a decision about what to do about a very sick child, that choice becomes a burden in itself regardless of the results. You wake up every day wondering if you did the right thing. If the doctor says “here’s what I think you should do,” the doctor takes on the burden. In the 23andMe case, I think there’s similar thing happening but it’s a burden of knowledge. If you know even possible future illnesses based on genetics, are you already paying a price just by having that knowledge?

I’ll give you a personal example of the burden of knowledge. When I was 25, doctors found out I had Hepatitis C. One of my doctors told me that my life expectancy was 30 years. Later, I found out that wasn’t true and since then I’ve been treated with Interferon and I haven’t had the disease for many years now. But that number, 30 years, stayed with me. It never went away. I have that burden of knowledge. In this case with 23andMe, the test service is creating a burden right now, and not helping to reduce it.

Does 23andMe have an obligation to be better with the information.

I think that they want to get better at it. It’s their mission to get people to make better decisions. In the realm of information that is frightening and worrisome, that’s not an easy thing to do. I met people in 23andMe and they are interested in the well-being of their users. When we did the tests with the people in my research lab I sent a report to them with our thoughts. My sense is that their heart is in the right place. From my perspective, doing the right thing and profiting form it is perfectly fine. It’s a simple starting point they began with: just give people the information and they’ll be better off with it. Now 23andMe need to refine their use of data. They have to have behaviorists on their staff and use them to make the information more useful. If you think you can just give people information and expect good response, no way. It’s way too much information and it is too expensive emotionally.

So how can they start to get better?

If I were their advisor I would make decisions for people. If the test reveals that you have a relatively high chance of colon cancer, but you can’t do anything about it, maybe we don’t even tell you that, but for sure not lead with this news front and center. But, if results suggest that you have a moderate chance of diabetes that you can control by changing behavior, I would emphasize that. I would lead with the family history and genetic mapping. It’s popular and less controversial. Next I would offer information and general suggestions for how you could improve life expectancy and quality of life, based on results that are actionable. Then, I would create another layer that would cost more to access and in that layer I would give all of the detailed information, including information about things that are largely out of your control. I would make that layer cost more because I want people to make an active choice to get that level of information. I basically want to make sure that people who go for that level of information want to invest in the burden of knowing. Even with all of this, I still think that the information communicated has to be better.

We know from research that most people are innumerate when it comes to risk. It’s not easy for us to understand what it means that you have a one in a thousand chance of something happening to you. How can you communicate risks like the chances you’ll get breast cancer in a way that doesn’t frighten people?

This is a really complex issue. If it says you’re likely to get Alzheimer’s–what does likely mean? And at what age? And how severely? There’s also something called focalism. Even if it’s an outcome that’s far away, by reporting it, you make a person focus on it and then they will exaggerate its likelihood or importance. Are you making people miserable, worried and upset for nothing? That was a big missing link for me in the results.

It sounds like this maybe shouldn’t be a consumer product yet?

I’m a big believer in technology and I think if it’s done right 23andME is a great product. I worry a lot that people don’t think about the future enough, and the lack of thinking about the future is a big part of my research. I think the ability to get people to look at the future in a meaningful way and help them shape it, could be very powerful. The promise is tremendous, the execution right now is not my favorite. I don’t’ want people to have the burden of information. I don’t want to frighten people. I don’t want to make them unnecessarily worried. And I suspect that simply giving people all the information will get them to act in all kinds of ways that aren’t optimal.

You said you were surprised by the one researcher who never used the kit. That seems to me to be, maybe not an optimal choice, but a very human one.

This person was thinking that there’s not much she would be able to do about most of what she would learn so the test would just reduce her enjoyment of living. That’s perfectly valid. We know many people get tested for dire diseases all the time and never pick up their results. It is a human response. We researched this general topic once. We asked people on a hot summer day at a local pool, what are the odds that someone had peed in that pool at some point earlier in the day, and the results came back where most people say something close a 100 percent, it was virtually certain that some kid peed in the pool. But people still used the pool. Then we asked them to imagine someone peeing in that pool right there while they were there watching, and asked how they would feel about going in after? You can figure out what they said. Sometimes a little ambiguity makes life much more bearable.

Why Japan’s Talent Wars Now Hinge on Women

“The majority — 65 percent — of our new recruits are women,” said the head of a foreign multinational I was working with in Japan last week. “We’re just going for the best, and the women are better educated and more mature.” Many foreign multinationals operating in Japan are beginning to understand that gender balancing historically male dominated workforces is proving an effective way to leverage both halves of the university educated talent pool – while shaking up traditional cultures with new, more ‘performance-oriented’ influences.

Still, how do you start to get older men to accept young female bosses in Japan? The HR Director explained how she focused on simply accelerating the already shifting ethos from tenure-based hierarchies to more performance and leadership-based priorities. Women served as leverage to make it happen, and then prove the benefits.

Foreign firms have recently figured out that proactive gender strategies offer a significant competitive edge. Especially as most smart, ambitious Japanese women would now rather work for a foreign company than be asked to serve tea in the seemingly-unchanging corporate cultures of Japanese firms. And most smart, ambitious men would still prefer the high-status boost of a big local brand.

In fact, Japanese companies seem to drive women away, in contrast to many countries where the gender balance is slowly but surely improving. According to data tracked by the OECD, Japanese women are among the least equal of women in any developed country. The WEF ranks Japan’s gender parity between Cambodia’s and Nigeria’s. But it’s not just kids and care-giving keeping them out of the workforce. A recent survey said the ladies are pointing at unsupportive managers and work environments that offer only dead-end part-time jobs. That has resulted in Japan having the developed world’s record (battling it out with South Korea) for the lowest number of women in management, around 10%.

A majority (68%) of Japanese women who identified themselves as career-minded or ambitious said they believed foreign companies are more woman-friendly than Japanese firms.

Too few Japanese companies are pushing for change, and even then usually at the behest of a foreign CEO. NISSAN is a good example, with Carlos Ghosn declaring he is “glad to be the poster boy of women’s empowerment… It’s not only about women but about men. I think there is a lot of wasted talent that the world cannot afford to waste.” The company’s hottest-selling car in Japan, the Nissan Note hatchback, is the result of a team led by a woman.

Even so, Nissan’s goals are somewhat modest: they aim to increase their ratio of female managers from 7 to 10 percent by 2017. That puts them well ahead of countrymen and competitors Toyota and Honda, for whom only 1% of managers are female. But it puts them very much behind US automakers, whose managerial ranks are 33% female, despite having no subsidized childcare or guaranteed maternity leave as Japanese women do.

Now the government is getting in the game, and the gender issue has become a part of Abenomics, the Prime Minister’s push to revitalize the Japanese economy. In a recent speech to Wall Street, he declared that “If these women rise up, I believe Japan can achieve strong growth”.

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is also recognizing the increasing power of women, reporting that “three out of every four big-ticket purchasing decisions are made by women alone or jointly with their husbands.”

Abe’s economic plan includes financial incentives for companies to promote women, expanded maternity leave, and increased day-care funding in an effort to get more women, especially mothers, back into the Japanese work force.

He’s even working on social norms by pushing dads to deliver at home too. If Abe’s plan works, Japan could add as many as 8 million workers to its slowly declining workforce.

But given the size of the challenge at hand, my bet is that Japan will be talking gender quotas in the coming decade. (Seem extreme? No one thought that Germany would get there either, and yet this is now a major negotiating point in Merkel’s new government formation.)

Japan needs more women working and more babies (yes, these two are mutually reinforcing) to counter an aging workforce and a flaccid economy. Japan may be the only OECD nation where the number of pets (25 million) exceeds the number of children (18 million under the age of 15). Facing this type of talent shortage, employers can play a key role in getting more women into every office. Will foreign companies show them the way? Or simply hire the best women, and leave Japanese firms in their male dominated status quo?

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

Research: Recession Grads May Wind Up Happier in the Long Run

Ten Essential Tips for Hiring Your Next CEO

Hiring and Big Data: Those Who Could Be Left Behind

How to Use Psychometric Testing in Hiring

Capitol Hill’s Productivity Problem

“This Congress Going Down as Least Productive,” blared the headline on the front page of Wednesday’s Boston Globe. As a productivity expert, my take on this is that it’s primarily a result of procrastination — one of the worst enemies of productivity.

Like most people, Senators and Representatives tend to procrastinate when confronted with difficult decisions such as raising the debt ceiling and passing the federal budget. Because Democrats and Republicans have such conflicting positions on these issues, they tend to make decisions only when coming up against a deadline.

Congress is now facing a series of deadlines over the next several months. Some of these are beyond Congress’s ability to control, notably the debt ceiling, which we will hit when we hit it. Others, Congress itself created, in particular the December target for agreeing this year’s budget. Indeed, Congress has often met a deadline by creating another one in the near future — ”kicking the can down the road.”

Missing deadlines is always bad, but not always catastrophic. If Congress is late on passing the federal budget, for instance, most of the federal government closes down for a few days or weeks. This result is bad, but not disastrous, for the American economy. By contrast, if Congress does not raise the debt ceiling on time, the result would be catastrophic. Such a “default”, even if temporary, would undermine global faith in US Treasury bonds for years to come. So Senators and Representatives should be careful not to procrastinate too long on really critical issues.

Unfortunately legislative inertia gives a tremendous advantage to the political party that benefits most when Congress does nothing, which only encourages procrastination. At the end of 2012, for instance, if Congress did nothing, all the Bush tax cuts would have automatically expired. Most Republicans were appalled by this possible outcome, although it was not so disturbing to most Democrats. As a result, Republicans were forced to cave into many demands of Democrats, who would have been relatively better off if Congress had done nothing on the Bush tax cuts.

We should expect, therefore, that Congress will continue to set deadlines, and wait until the last minute to meet them, as long as there is such a wide ideological gulf between Democrats and Republicans.

Sadly, this divide is likely to persist. Most House seats are “safe” for one party because Congressional districts have been gerrymandered by state legislatures. In the 2014 election, for example, there are only 36 “competitive” seats out of a total of 435 House races. So most Representatives have no political incentive to take moderate positions or compromise on legislation.

Much the same is true for Senators. Candidates are usually chosen in separate statewide primaries, where party faithful dominate the voting. Party faithful tend to represent the wings of each part: the right wing for Republicans and the left wing for Democrats. For example, Senator Robert Bennett, a staunch conservative but pragmatic legislator, lost the Utah Republican primary by a few votes in a low turnout primary to a Tea Party candidate.

In short, the low productivity of Congress is the result of significant structural flaws with our political system. If we want more productivity and less procrastination in Congress, we will have to change the redistricting process and primary system in most States.

Five Ways to Learn Nothing from Your Customers’ Feedback

I have studied a lot of customer feedback systems in the 25 years I’ve spent working with companies on customer strategy. Many of them leave me sad and befuddled. So many companies make the same mistakes over and over.

The leaders of these companies seem to want to hear from their customers — that’s why they spend so much money on elaborate “voice of the customer” and other feedback systems. But the approach many of these companies take to implementing such systems seems almost as if it were designed to ensure nobody in the organization will actually learn anything from what they hear. And if employees don’t learn anything, how can they take action to make things better?

If I were writing a “how-not-to” manual for customer feedback — a manual that would guarantee your feedback system taught your employees nothing about how to delight customers and earn their loyalty — here are the five rules it might include:

1. Aggregate the feedback into scores, percentages, and averages — and stop there. This common mistake completely obscures any individual customer’s voice and prevents employees from linking the feedback to a particular event, behavior, or action they can remember. Yet there’s something irresistibly seductive about numbers that seem so rigorously mathematical. “Congratulations! Customer satisfaction increased 0.431% this quarter! Great job!” Of course, most companies try to figure out what drove the improvements by breaking down each summary score into dozens of “drivers,” but the typical result is that employees get lost in a sea of analysis and numbers. In fact, this becomes much worse when scores decline. That’s when the analysis really gets overwhelming.

2. Hold the feedback. Many companies distribute summaries of what they hear from customers six, eight, or even 12 weeks later. This is a byproduct of the first rule because turning customer feedback into statistics usually requires aggregating it for several weeks in order to collect enough observations. All that analysis and reporting takes time to assemble, too. How well do you remember each of the many conversations and interactions you had six weeks ago? Chances are your employees don’t either — which makes it awfully tough for them to remember what they did that might have contributed to variations in their customers’ feedback.

3. Eliminate the human voice. How often have you taken a company’s survey because you wanted to register your annoyance (or delight) with the company’s actions, only to discover that none of the questions seemed like they really addressed the issue on your mind? Too many companies ask customers to rate their performance on a predetermined list of factors — typically offering many prompts covering every conceivable element of the company’s product or service. Multiple-choice questions are convenient for your company to process and analyze, but they impose a burden on your customers. More importantly, they don’t give customers a chance to share their feedback in their own words. Do you know better than your customers exactly what issues they face and how they should describe them?

4. Ensure that there’s a lot at stake. If you want your employees to focus maniacally on customers, what better way than to put money at stake, right? But tying people’s compensation and promotion prospects to changes in your customer-satisfaction metric doesn’t focus them on customers; it focuses them on a number. And, as I’ve discussed before, that can lead to a lot of behaviors that might be maniacal but are not customer-focused. More often than not it leads to begging customers for higher scores or discouraging angry customers from providing feedback. It’s also likely to prompt debate about the basis for the score every time employees or departments are off-track for meeting their goals.

5. Never close the loop with customers. Historically, the vast majority of customer feedback was anonymous. It was collected in a “market research mode,” which meant no one could follow up with individual customers to address their issues directly. The flawed logic behind this was built on a belief that customers would not share honest feedback unless their identity was kept secret. That might be true in some circumstances, but in my experience, it’s rare. Anonymity in customer feedback is, frankly, overrated. People want to be heard. They want their feedback to be acknowledged. They want to know that the time they invested sharing feedback meant something and was acted on. Closing the loop is essential to building lasting customer relationships, and it is an invaluable opportunity to dig more deeply into the details of what delighted or enraged them. It offers an opportunity to begin digging into the root causes of customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction to uncover policy problems, issues with product design, or other pesky issues that require cross-functional collaboration.

Of course, no company intentionally follows this “how-not-to” rulebook. And yet, like me, I bet you have seen at least one company that follows all five of these rules, and maybe more.

The truth is, creating an organization that really listens to its customers — what many call a customer-centric culture — is difficult. That’s why so many companies have moved from traditional customer satisfaction approaches rooted in a “market research mode” to customer feedback systems deeply integrated into daily operations. Real-time feedback from “voice of the customer,” the Net Promoter SystemSM, or other feedback mechanisms can deliver customer responses directly to the employees who need to hear them, soon after they took the actions that generated them. This sort of closed-loop feedback makes it easier to learn from experience. I dare say that a good deal of what accounts for the popularity of these approaches is the frustration many leaders feel about how little their employees have been learning from customers.

If you want employees to learn from customers, don’t follow the traditional approach to customer satisfaction measurement. Make feedback a part of your daily operations. Deliver the feedback directly to the employees who need to hear it. Focus your company’s customer listening efforts not on measuring more precisely, but on learning more effectively.

How to Fund Indian Start-Ups

Even though interest in entrepreneurship is at its highest in India, the country has a nominal seed capital infrastructure. India has numerous small retailers and service providers who are shining examples of scrappy entrepreneurship at its best, but the information technology startups that are my primary interest typically require outside funding.

With that in mind, how do we find new ways to fund India’s tech startups and build global businesses?

India has done well in the last twenty odd years to build its technology industry through services. Today we’re seeing a maturing of the industry, and entrepreneurs now want to build products as well. Or they want to build online businesses: e-commerce, mobile apps, so forth. Sometimes they want to build hybrid businesses–both online and physical. Or they want to combine products and services.

As far as I am concerned, all those permutations and combinations are fine. However, in today’s India, building capital-intensive businesses is difficult. Even more difficult is to build a business that requires capital out of the gate.

If you can bootstrap your way to validation and revenue, ideally, to profitability, then there is plenty of capital available. However, if you need capital to validate, you are operating in a zone that will be full of very dark hours.

All risk capital in India is in effect growth capital. You will need to absorb the risks yourself, and present a growth opportunity to angels and VCs. If you can bootstrap your way to, say, $1 million in revenue, there is enough capital out there to give you $5 million or $10 million to get to the next level.

But if you need funding in the seed stages, before validation, there is very little capital in the system.

My friend Sharad Sharma, an active angel investor, sums up the situation well:

“The US does more seed deals by 11am in a single day than India does in a year. I haven’t dug up the 2012 numbers. But in 2011, $30 billion was invested by angels and $24 billion by Series A venture capitalists. If one assumes each angel deal was $300,000 per deal, then about 100,000 deals were done in 2011. That is about 500 deals per working day. In India, Indian Angel Networks did 13 deals last year, Mumbai Angels about a similar number, Harvard Angels did three, Chennai Angels did six, etc. The optimistic number for the number of angel deals would be 100. Even the most optimistic observer who’d count every informal deal would not put it past 200. So the Indian seed stage ecosystem is really small. This is not what the media makes it out to be.”

More recently, there is an over active incubator network that has taken hold. The Indian government is offering money for people to set up incubators, which has led to a lot of clueless people setting up incubators. They promise seed funding to naïve entrepreneurs who, more often than not, are entirely unfundable. They lack the experience or skills to mentor entrepreneurs and teach them what needs to be taught. Several VCs, who for obvious reasons do not want to be quoted, have complained to me that “incubators” and “advisors” in India are dishing out bad advice to unsuspecting entrepreneurs. Some even run scams like asking for 5-10% equity to “introduce” founders to angel investors. And most claim to “graduate” entrepreneurs from their programs in 3-6 months with nothing to show.

Given this rather messy environment, entrepreneurs have a few pragmatic choices on how to navigate the seed stage bottleneck:

Bootstrap with Services: Many Indian IT entrepreneurs come from the services industry background. Using IT services to generate cash and develop customer intimacy, it is entirely possible to build products. We have numerous case studies of this being a tried and true procedure, and recommend it strongly.

Bootstrap with a Paycheck: Many aspiring Indian entrepreneurs are currently sitting on the sidelines, not yet ready to play. I suggest you hold on to your paycheck, and start validating your idea. Learn what it takes to build a business. There are concrete, defined ways in which you can do so. Especially if you are building online businesses, this is an excellent strategy. Quit your job only AFTER your fledgling business achieves a certain level of validation.

Friends and Family: Historically, in India and elsewhere, entrepreneurs have built businesses with the backing of their friends and family. The biggest difference between professional investors and friends and family is that the latter cares about YOU.

The Indian market is a slow adopter of new technologies. As such, you cannot expect to be able to get to a product-market fit in three months. It may be 18-36 months before your venture really starts to find its stride.

Until then, you are better off sticking to one of the three above principles of bridging your capital gap.

In summary, there is a miniscule pool of seed money in action in India currently. Most of this money will go to validated businesses, not to concepts, and not to entrepreneurs experimenting with concepts.

Stop wasting time chasing capital unless you have reached sufficient maturity.

In India, by and large, the definition of seed capital is misunderstood by naïve entrepreneurs. They think entrepreneurship is sexy, and investors are sitting around, waiting to write checks for them to start their businesses.

This expectation needs to change.

As angel investor Nandini Mansinghka puts it, “Seed capital needs to return to its old-fashioned definition of people who know you putting in money in your venture, because they believe in you rather than your core idea. The only difference as we mature as an ecosystem, is these known people will not just be family, but the extended network built both personally and digitally.”

And if you don’t have such friends and family to help you get off the ground, then focus on the other two options: bootstrap with services, or bootstrap with a paycheck.

In India as it exists today, those are your options.

Pilferage from Mail Remains Significant Problem in Emerging Countries

One of the developmental barriers faced by emerging economies is the unreliability of local mail. For example, a team led by Marco Castillo of George Mason University discovered that more than 18% of envelopes sent from the United States to households in Lima, Peru, didn’t arrive at their destinations, and envelopes containing money were 50% more likely to be “lost” than others. “Clearly, those who handle the mail are looking for clues that might suggest that an envelope holds something of value,” the researchers say.

Big Data’s Biggest Challenge? Convincing People NOT to Trust Their Judgment

Here’s a simple rule for the second machine age we’re in now: as the amount of data goes up, the importance of human judgment should go down.

The previous statement reads like heresy, doesn’t it? Management education today is largely about educating for judgment—developing future leaders’ pattern-matching abilities, usually via exposure to a lot of case studies and other examples, so that they’ll be able to confidently navigate the business landscape. And whether or not we’re in b-school, we’re told to trust our guts and instincts, and that (especially after we gain experience) we can make accurate assessments in a blink.

This is the most harmful misconception in the business world today (maybe in the world full stop). As I’ve written here before, human intuition is real, but it’s also really faulty. Human parole boards do much worse than simple formulas at determining which prisoners should be let back on the streets. Highly trained pathologists don’t do as good a job as image analysis software at diagnosing breast cancer. Purchasing professionals do worse than a straightforward algorithm predicting which suppliers will perform well. America’s top legal scholars were outperformed by a data-driven decision rule at predicting a year’s worth of Supreme Court case votes.

I could go on and on, but I’ll leave the final word here to psychologist Paul Meehl, who started the research on human “experts” versus algorithms almost 60 years ago. At the end of his career, he summarized, “There is no controversy in social science which shows such a large body of qualitatively diverse studies coming out so uniformly in the same direction as this one. When you are pushing over 100 investigations, predicting everything from the outcome of football games to the diagnosis of liver disease, and when you can hardly come up with a half dozen studies showing even a weak tendency in favor of the clinician, it is time to draw a practical conclusion.”

The practical conclusion is that we should turn many of our decisions, predictions, diagnoses, and judgments—both the trivial and the consequential—over to the algorithms. There’s just no controversy any more about whether doing so will give us better results.

When presented with this evidence, a contemporary expert’s typical response is something like “I know how important data and analysis are. That’s why I take them into account when I’m making my decisions.” This sounds right, but it’s actually just about 180 degrees wrong. Here again, the research is clear: When experts apply their judgment to the output of a data-driven algorithm or mathematical model (in other words, when they second-guess it), they generally do worse than the algorithm alone would. As sociologist Chris Snijders puts it, “What you usually see is [that] the judgment of the aided experts is somewhere in between the model and the unaided expert. So the experts get better if you give them the model. But still the model by itself performs better.”

Things get a lot better when we flip this sequence around and have the expert provide input to the model, instead of vice versa. When experts’ subjective opinions are quantified and added to an algorithm, its quality usually goes up. So pathologists’ estimates of how advanced a cancer is could be included as an input to the image-analysis software, the forecasts of legal scholars about how the Supremes will vote on an upcoming case will improve the model’s predictive ability, and so on. As Ian Ayres puts it in his great book Supercrunchers, “Instead of having the statistics as a servant to expert choice, the expert becomes a servant of the statistical machine.”

Of course, this is not going to be an easy switch to make in most organizations. Most of the people making decisions today believe they’re pretty good at it, certainly better than a soulless and stripped-down algorithm, and they also believe that taking away much of their decision-making authority will reduce their power and their value. The first of these two perceptions is clearly wrong; the second one a lot less so.

So how, if at all, will this great inversion of experts and algorithms come about? How will our organizations, economies, and societies get better results by being more truly data-driven? It’s going to take transparency, time, and consequences: transparency to make clear how much worse “expert” judgment is, time to let this news diffuse and sink in, and consequences so that we care enough about bad decisions to go through the wrenching change needed to make better ones.

We’ve had all three of these in the case of parole boards. As Ayres puts it, “In the last twenty-five years, eighteen states have replaced their parole systems with sentencing guidelines. And those states that retain parole have shifted their systems to rely increasingly on [algorithmic] risk assessments of recidivism.”

The consequences of bad parole decisions are hugely consequential to voters, so parole boards where human judgment rules are thankfully on their way out. In the business world it will be competition, especially from truly data-driven rivals, that brings the consequences to inferior decision-makers. I don’t know how quickly it’ll happen, but I’m very confident that data-dominated firms are going to take market share, customers, and profits away from those who are still relying too heavily on their human experts.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

Small Businesses Need Big Data, Too

How to Get More Value Out of Your Data Analysts

Big Data Demands Big Context

How a Bathtub-Shaped Graph Helped a Company Avoid Disaster

December 6, 2013

Who’s Hiring (and Who Isn’t) in Five Charts

Five years after the start of the worst six months for the U.S. labor market since the Great Depression, we learned Friday that 203,000 new jobs were created in November and the unemployment rate dropped to 7%. Discussion in the immediate aftermath of the news centered on whether the report marked more of the ho-hum same or a sign that, after three years of puttering along, the economy might finally be preparing for a return to something approaching prosperity.

We won’t know who’s right about that for months, maybe even years. So let’s look back instead. First, briefly, back to November 2008. U.S. employers had been shedding jobs for a few months already, but in November it turned into a mass defenestration: 775,000 jobs lost. And it went on like that for five more months. March 2009 was the worst, at 830,000 jobs lost. (These numbers, as with all those that I’ll cite here, are adjusted to iron out seasonal factors such as the customary rise in retail employment before Christmas and bust soon after.) The total for the six-month period: 4.5 million jobs lost. For the entire two-year-long contraction: 8.6 million. And we still haven’t gotten those jobs back. At 136.8 million jobs in November, civilian nonfarm employment in the U.S. is almost 1.3 million below its January 2008 all-time peak.

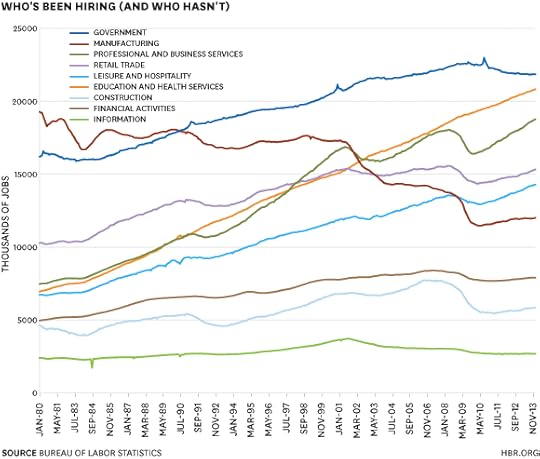

That’s not true of every industry, though. A few kept setting new employment highs even during the recession; others have kept declining even during the recovery. Cyclical fluctuations have a big impact on employment, and the worst recession in 75 years has an especially big impact. But over time it still pales next to secular shifts in the economy. And secular shifts make for cool charts! To start, here’s how things have gone for the main broad job categories (and three smaller ones of interest: finance, construction, and information) since 1980:

The most remarkable line in the chart is education and health services, which just keeps rising and rising, paying no mind whatsoever to the rest of the economy. This is mostly about health care, which accounts for 70% of the jobs in the category and has been adding them much faster than the educational sector. It’s also an understatement, as employment at public schools and government-owned hospitals shows up in the government category.

The government employment line is interesting, too. The number of government jobs peaked in April 2009 at almost 22.7 million, and while it seems to have stopped declining in the past few months, it isn’t really rising, either. This has been mostly a phenomenon of local governments, which account for 64% of government employment in the U.S. and were hit hardest by the decline in tax revenue in the aftermath of the housing crash and recession. Federal government employment, if you don’t count the once-in-a-decade binges of Census hiring (the funny little spikes in the government line), actually peaked back in the late 1980s. To repeat, the U.S. government has fewer employees now than it did in 1989. This doesn’t count non-civilians such as soldiers, CIA agents, and NSA snoops, but there’s no way that even big increases in employment at the latter two would make up for the 500,000+ decline in active-duty military personnel since 1990.

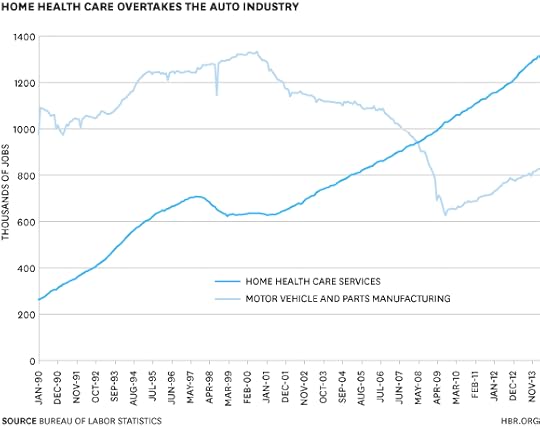

Beyond that, the chart mainly shows the already flogged-to-death contrast between rising service industries and declining manufacturing. Yes, manufacturing employment has been rebounding since bottoming out in 2009, but it’s from an awfully low base. For a more dramatic version of this, here’s the once economy-dominating auto industry plotted against an especially fast-rising category: home health care services:

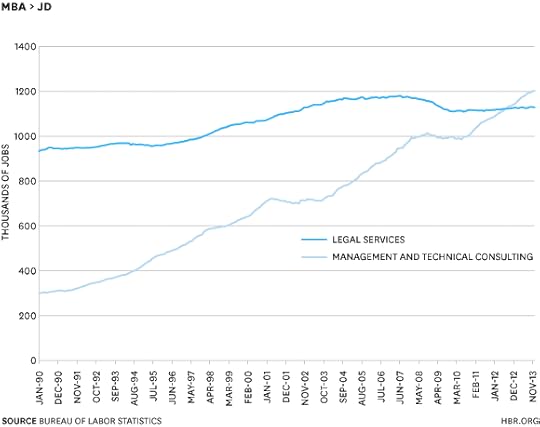

The average hourly wage in the home-health-care sector, in case you were wondering, is $18.90. Among motor vehicle and parts workers it’s $24.06. That’s actually not as big a gap as I expected, but it does fit the oft-decried model of better-paid fields losing ground to worse-paid ones. Still, not every tale of changing fortunes in the workplace has such a discouraging ending. The average hourly wage in management and technical consulting is $37.44; in legal services it’s $37.07. And look who’s winning that jobs race:

As for the headline, yeah, yeah: most of the people in “management and technical consulting” jobs probably don’t have MBAs. But the chart does pretty dramatically illustrate the tough times the legal profession has been going through for the past decade. And while Clay Christensen, Dina Wang, and Derek van Bever say the consultants are next, it’s not showing up so far in the jobs numbers.

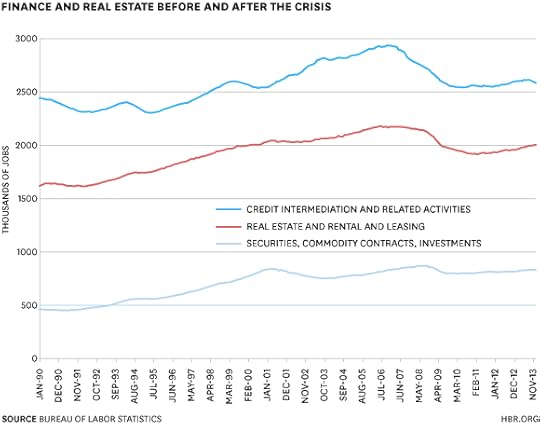

One sector that was booming up until the crisis and then tanked spectacularly was of course the financial-real-estate complex. One thing that’s a little surprising to see, in the first chart of this post, is that finance isn’t one of the really big job categories. True, there’s a bunch of real-estate-related jobs outside the category (construction, home-improvement retailers), but for all its impact finance itself just isn’t that big an employer. As for what’s been happening within the sector, credit intermediation (banks and other lenders) took a really big hit and seems to have started shedding jobs again, real estate has held up a bit better, and “securities, commodity contracts, investments” (Wall Street, more or less) has held up best of all. The dot-com bust appears to have hit it harder than a global financial crisis did:

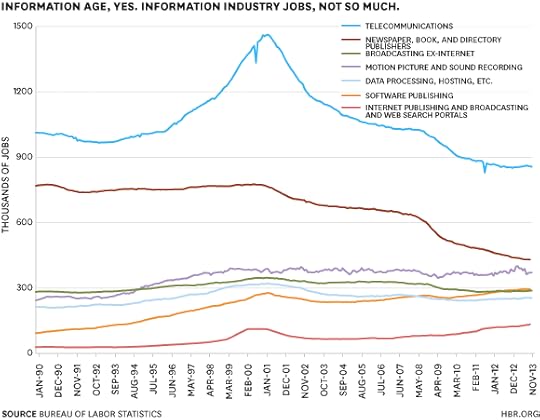

The average hourly wage in that last sector is $48.82, by the way. Which is a lot higher than the $27.49 hourly wage at newspaper, book, and directory publishers (which includes magazines). We all know it hasn’t been going well for old media, as my final chart clearly shows. What’s interesting, though, is that information industries in general haven’t really been contributing to job growth. The growth in software and Internet publishing is nice, but they just don’t account for all that much employment, yet:

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

Research: Recession Grads May Wind Up Happier in the Long Run

Ten Essential Tips for Hiring Your Next CEO

Hiring and Big Data: Those Who Could Be Left Behind

How to Use Psychometric Testing in Hiring

Get More Value Out of Social Media Brand-Chatter

It’s becoming commonplace for consumer companies to listen to what their customers are saying on social media, but the big question is: What do they do with the results? In a lot of cases, managers merely circulate them within the marketing department—after marking them with a prominent “FWIW.”

That’s because they don’t know what this information could be worth.

Companies don’t realize that with proper care and handling, insights harvested from social listening can become as robust a source of strategic inspiration as any must-have diagnostics on the dashboard.

Social listening is inexpensive too, in the sense that it has a high insight-to-dollar ratio. That’s because you don’t have to survey or interview anyone—unsolicited comments from engaged customers are already out there, waiting to be analyzed. And social-media data are continuous—you don’t have to depend on quarterly or annual consumer surveys that are out of date before they’re even analyzed.

To tap social listening’s potential as a source of strategic inspiration, think like a market researcher and follow these sensible steps:

Make sure the quality of your social-listening data is good. Like all data, the information you glean from social media should be subject to market-research protocols for reliability and validity. Ask the same kinds of tough questions you’d ask about any research project. Are the data drawn from the entire social-media landscape? Is the sampling of comments statistically sound? Is the system of data classification, in terms of topics, themes, and sentiments, accurate? Does your automated coding allow for idiomatic meanings, as in “This brand is the s—t”? The insights you get from social media are only as good as the data set you create.

Don’t make your social-media data stand alone. Information from social listening must be correlated with other streams of data that the company is using. For example, in an analysis we performed for a transport company, we found that complaints shared on daily Twitter feeds tracked 90% with the content of customer-service comments registered by phone or mail. Linkages like this go a long way toward speeding the adoption of social-media data as a valid strategic-insight source.

Sometimes the correlations are low between what you think you know and what social listening reveals. But that doesn’t mean you should jettison the listening data; it just means you need to consider both sets of findings simultaneously to decipher the true story.

In collaboration with a beer manufacturer, we conducted a brand-positioning analysis of three leading brands. Conventional wisdom at the company dictated that differentiation based on taste was not an option. Studies had demonstrated, time and again, that consumers could not pick out their favorite beer in blind taste tests. This finding had underpinned positioning and communication decisions for years.

But online comments revealed a different picture: Consumers went deeply into stories about the taste and sensory experiences of not just the beers they loved, but also of those “watered-down, hangover-inducing” beers they disdained. It turned out consumers thought they could pick their favorite beers out of a lineup. And perception, not reality, was what mattered in this space. The social-listening data allowed a marriage between the quantitative and the qualitative. Customer stories illustrated the insights, and the raw numbers (thousands of online statements) validated the insight, allowing the company’s conventional wisdom—and the branding programs guided by it—to slowly change.

Think about “impact” and not just ROI. Marketing managers tend to take too narrow a view of social listening, seeing it merely as a way to measure the return on investment of specific marketing campaigns. For example, an electric-toothbrush maker that had launched a campaign to woo “non-electric” brushers was dismayed to learn that the resulting burst of social-media activity came mostly from existing users. It branded the campaign a flop and moved on.

In so doing, the company overlooked the value of what it had found on social-media sites. Users were sharing positive stories, advocating electric brushing, and in some cases expressing their love of the company’s brand. The company was getting a rare unfiltered look at how consumers were living the impact of the company’s strategies and brands.

Be sure your social-listening analyses make their way out of the marketing-research department and into the wider organization, including leadership circles. Don’t let the information stay bottled up in the departments that collected and “own” the data. That means establishing a common analytical currency and language throughout the company so that managers can take action and be held accountable. One company we worked with created a Center for Digital Excellence to coordinate data on a vast brand portfolio. The company tied the digital indicators to bonus compensations, signaling C-level commitment to the program. It’s that kind of high-level integration that enables companies to focus efforts and resources effectively, creating value for the firm.

It’s not simple to turn large volumes of unstructured data into analyzable formats and insights. But it can be done. And it must be done—social listening is too valuable to be relegated to the “for what it’s worth” category.

Happy Workaholics Need Boundaries, Not Balance

Success is typically a function of our passion for work and accomplishment—my clients and students are generally “happy workaholics” who love what they do and wish there were more hours in the day to get things done. (I view myself this way as well.) The concept of life/work balance isn’t that helpful for us, because there’s always more work to do, we’re eager to do it, and we wouldn’t have it any other way. In some cases, particularly in junior roles early in our careers, this tendency can be exploited by a dysfunctional culture or an uncaring manager, and at those times we need to protect ourselves to avoid burnout. But as we advance professionally we’re less subject to those external forces, and we need to protect ourselves primarily from our own internal drive.

Here’s one way to think about protecting yourself. Years ago my colleague Michael Gilbert suggested that we substitute “boundaries” for “balance”: while balance requires an unsteady equilibrium among the various demands on our time and energy, boundaries offer a sustainable means of keeping things in their proper place. Gilbert drew upon his training as a biologist in his definition of healthy boundaries: “Just as functional membranes (letting the right things through and keeping the wrong things out) facilitate the healthy interaction of the cells of our bodies, so do functional personal boundaries facilitate the healthy interaction of the various parts of our lives. Bad boundaries lead to either being overwhelmed or withdrawal. Good boundaries lead to wholeness and synergy.”

What does this look like in practice? What types of boundaries do we need?

Temporal boundaries designate certain times exclusively for family, friends, exercise, and other non-work pursuits. Note that I’m talking not about balance but about boundaries; the amount of undisturbed time we preserve for certain activities will vary and may be quite small, but what matters is that we create and maintain a functional boundary around that time.

Physical boundaries ensure that we get out of our offices and workplaces at regular intervals and create actual distance between us and our work (which includes not only the office itself but also all our professional tools and artifacts–laptops, tablets, phones, papers, everything.) Again, the question is not about balancing the two worlds, but establishing boundaries to create the needed separation.

Cognitive boundaries help us resist the temptation to think about work and focus our attention on the people or activity at hand. This is by no means an easy task, particularly given that so much in our work environment is designed to capture our attention (email alerts, message reminders, innumerable blinking lights and flashing icons). Recognizing when our attention is being held hostage by work and turning it elsewhere requires persistent, dedicated effort, but it yields substantial rewards, in part because our focused attention is one of our greatest resources. (And one reason I often recommend meditation is an improved ability to control where we direct our attention.)

This subtle shift – eschewing balance and establishing boundaries – isn’t easy work, but it’s worthwhile in trying to protect us from ourselves.

Many of my executive coaching clients and MBA students at Stanford are going through a transition that involves a step up to the next level in some way. They’re on the cusp of a big promotion, or they’ve launched a startup, or their company just hit some major milestone. Very few, if any, of these people would say that they’ve “made it”; they’re still overcoming challenges in pursuit of ambitious goals. And yet their current success has created a meaningful inflection point in their careers; things are going to be different from now on. The nature of this difference varies greatly from one person to another, but I see a set of common themes that I think of as “the problems of success.” You can read my first post here.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers