Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1498

December 11, 2013

An Unexpected Lesson from Mandela: Why Context Matters

During this time of global contemplation on the deep legacy of Nelson Mandela, I realized I have my own connection to this “giant of history,” which traces back to those heady days of South Africa in 1994. What did I learn from him? Business cannot be left alone to be just business, and, as I learned in Pretoria nearly 20 years ago, leaders ignore this bigger picture at their peril.

From 1994 to 1995, I was traveling across Africa, exploring interest among various governments and telecommunications service companies in investment in the continent’s first undersea fiber-optic network. This would be a breakthrough communication technology, with the power of connecting an excluded and fragmented continent with itself, with the world, and to this newly emerging phenomenon — that none of us quite understood at the time — called the Internet.

Given its economic heft, South Africa was among my first ports of call. Those were exciting times for the country. The ANC had just assumed power and Mandela had made history as the country’s first black president. The world was suddenly considering how to connect to this hitherto isolated country and embracing a potential economic and political powerhouse.

I made what I thought was a brilliant presentation to senior bureaucrats and technologists. In my view, I had quite convincingly made the case for South Africa to be the key anchor for a fiber-optic ring that would encircle the continent with branches taking off toward other continents.

Turns out, my case wasn’t as rock solid as I had imagined. A senior minister took me aside the next day and asked if we could scrap the plans for a ring around Africa and just do a single cable that linked South Africa to …. Malaysia. That’s it. Just Malaysia. But that makes no business sense whatsoever, I protested. The minister explained that Mandela had visited Malaysia the previous year and had struck up a close friendship with Prime Minister Mahathir. The two had agreed on cooperation on many fronts. Most significantly, Malaysia had pledged help in providing voter education to South Africa, a country where nearly 18 million out of the 20 million citizens would cast their ballots for the first time, with half of the 18 million illiterate. And now, post-election, it was critical that the bonds be strengthened further.

“But consider the economics,” I continued. “A single link to Malaysia would be frightfully expensive and would not have the traffic to justify it. You would forgo the chance to connect with the rest of Africa.”

The minister politely, but firmly, let me know that while I seemed smart enough, I was not as clever as I thought I was. “You do not argue with Nelson Mandela,” he said.

Trained as an economist, this was my first small step toward an appreciation for contextual intelligence. The linear logic of business and all its analysis could not — and should not — ignore the momentum of emerging geopolitical alliances. Malaysia was already among the first of South Africa’s allies; there was a stronger relationship to be built. Mandela had personally asked for this cable as a symbol and a conduit.

Still frustrated, I walked the corridors of South Africa Telkom and ran into the old guard. These were engineers and network planners; surely, they understood economics and net present value analysis. I told them my story. They agreed that the Mandela proposal was nonsense. What was needed was a fiber-optic link directly connecting South Africa to Northern Europe. “What about the connectivity to rest of Africa?” I asked.

“Who cares about the rest of Africa?” was the universal opinion.

This was my second lesson in contextual intelligence. The old guard was all white. They were frightened about what was going to come next as their secluded reality had come to an end. While their argument was couched in business terms (after all, Northern Europe was where the business would be), their real reason was in history: They desperately wanted a conduit back to the old days and to some semblance of a world that they had known all their lives. They were ready to make a “business” argument that was, in reality, an agenda that harkened back to a colonial legacy.

Yes, I was there at a true inflection point, armed with the finest analysis possible, elaborate layers of spreadsheets, and well-crafted presentations. However, real decisions are based on a myriad other factors. In this case, there was, first, a big future envisioned by a master politician — and already a living legend — who could imagine the unimaginable. And second, there was a past that, while it had become politically irrelevant, still had the technocratic expertise to exert a pull in an opposite direction. If South Africa was to develop, it could not afford to ignore the technocrats entirely.

I re-did the analysis. We modeled-in the geo-political assumptions, accounted for different connectivity scenarios and their socio-political ramifications as well as economic impact. We resumed the debate in a more holistic manner. Context is, indeed, king. You should embrace it, understand it, and make it central to your business model analysis; most importantly, you should not ignore or fight it.

There is a larger lesson here for today’s business leader. With half the world’s output and two-thirds of the world’s growth coming out of countries that are still “emerging,” it is important to recognize the centrality of context. The context in these countries is complex and different from what we are familiar with in the industrialized west. It is bound to emerge at an even slower pace. We should factor-in how business decisions connect with non-business factors, such as politics, history, and the human condition.

I have taken this lesson to heart, so much that I now run an institute whose mission is to help tomorrow’s leaders make these connections. I now know the importance of contextual intelligence in a business leader. And it all started with an unexpected lesson from Mandela.

10 Charts from 2013 That Changed the Way We Think

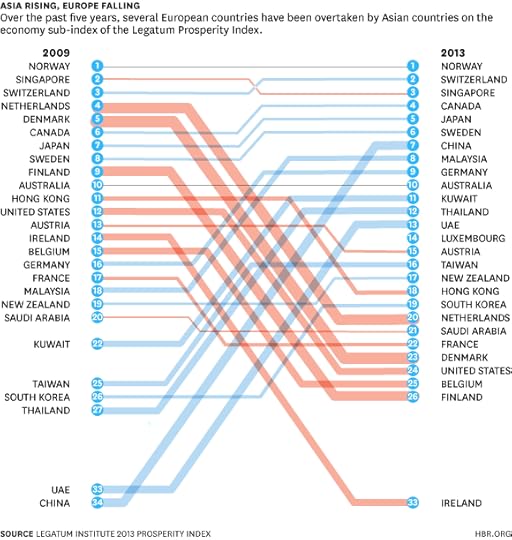

1. Asian countries are overtaking European countries when it comes to prosperity:

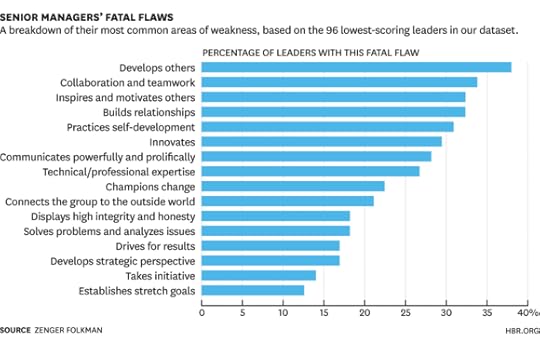

2. The most common area of weakness for ineffective senior leaders is their ability to develop others, followed by their ability to collaborate (but research shows it’s entirely possible to reverse these bad habits):

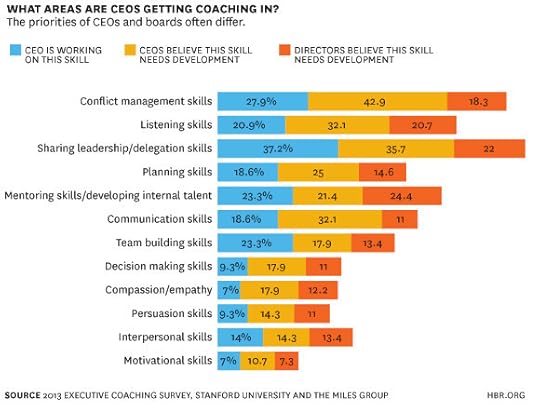

3. Here are the areas CEOs are getting coached in — but priorities differ depending on who you ask:

4. Go ahead, expense that chicken:

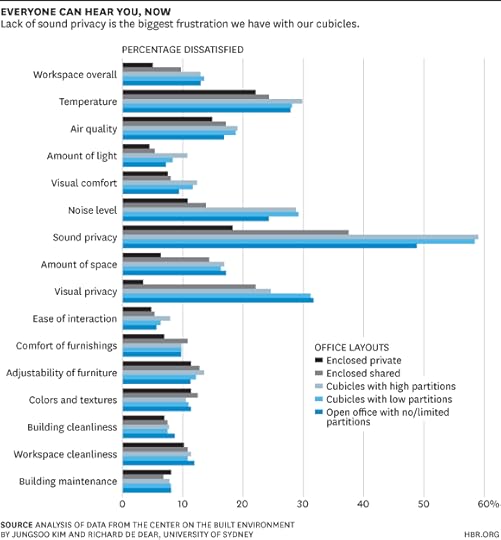

5. Cubicles are the absolute worst, in part because they’re so darned noisy:

6. What percentage of U.S. mothers work 50 or more hours a week during the key years of career advancement? Most people say half — and they’re wrong:

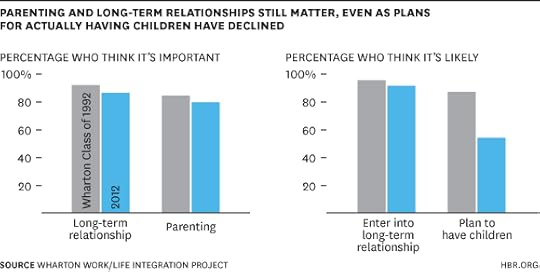

7. Even though recent Wharton grads say that parenting still matters, fewer and fewer think they’ll end up having kids:

8. It may be a good time to invest in Africa, which is more stable than you’ve been led to believe:

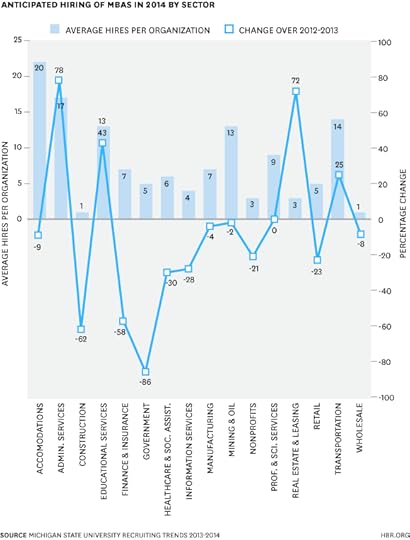

9. You’re probably in good shape if you’re set to graduate from a top-tier business school. If not, there’s reason to worry due to these hiring patterns:

10. And, just in time for bonus season, you may want to forgo those involving cash if your goal is increasing productivity:

Case Study: When the Twitterverse Turns on You

Charlene Thompson reached for her phone on the nightstand. It was still before 6:00am, so the iPhone’s glow was the only light in the room. Her husband, James, turned over and groaned.

“That’s a horrible habit,” he said. “You should always have coffee before checking your inbox.”

“This is important, honey,” she whispered. “I need to see what’s happening with the contest.”

(Editor’s Note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.)

Charlene was the head of public relations for Canadian Jet. Yesterday, with the help of the company’s PR firm, Wrigley & Walters, the airline had launched its first Twitter contest: The person who posted the most creative tweet using the hashtag #CanJetLuxury would win two round-trip tickets to any of the company’s destinations.

For Charlene, who had led the airline’s communications for 15 years, this campaign was critical. Six months before, a third of Canadian Jet’s fleet had been grounded for a week owing to some engine safety concerns, causing a slew of cancellations and delays. There had also been some negative press about the airline’s approach to labor relations following a threatened strike by the ground crews. The team at Wrigley & Walters had designed this campaign to restore Canadian Jet’s image as a preferred carrier.

“Shoot. This isn’t good,” Charlene said as she scrolled through an endless string of tweets.

“What? It’s not catching on?” James asked groggily.

“Just the opposite. But not in a good way.” She read a few of the tweets: “’Getting to my destination without the engine catching fire #CanJetLuxury’; ‘Being stranded 3,000 miles from my family for two days straight #CanJetLuxury’; #CanJetLuxury is getting away with not paying employees fairly.’”

“Ouch,” James said.

This is completely backfiring, Charlene thought as she got out of bed.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

“I need to call Jerry.”

7:30am

Jerry Schneider, Canadian Jet’s CEO, was tapping his fingers on his desk while he and Charlene waited for the others to arrive. He hadn’t said much yet, but Charlene could tell that he was feeling the stress, too.

Tim Powell, Charlene’s director of social media, showed up with Andrea Kemp, the company’s account manager from Wrigley & Walters. Both looked flustered.

“Sorry,” Tim said. “We had trouble getting Andrea’s pass.”

Andrea shook Jerry’s hand and started speaking before she sat down.

“OK, so we knew this was a risk going in, right? People love to complain on the internet, especially when they can essentially be anonymous like this.” Charlene knew Andrea’s fast talking wasn’t a sign of nerves. She was just the sort of person who was energized by a crisis. And she was right — throughout the planning process, she’d reminded Charlene and her team that critics could use social media campaigns like this one to bash the company. JPMorgan Chase had been a recent victim of hashtag backlash after launching a well-meaning Twitter Q&A, she told them, and she had sent around a Forbes.com article about how one of McDonald’s campaigns has resulted in a “bashtag.” She reminded them now of these other cases.

“I’m not sure knowing we’re in good company is any comfort right now,” Jerry said. He asked Tim for an update.

“They’re still coming in: 200 more tweets with the CanJetLuxury hashtag since 6am. The majority are fine — good, even — but there are some doozies.”

Jerry rolled his eyes. “I don’t even want to hear any more.”

“And we’ve started trending, which isn’t great, given the circumstances,” said Tim.

“How do we stop trending?” Jerry asked. The CEO was three decades removed from the Millennials, and although he did his best to keep up with social media, he wasn’t as savvy as Tim or Charlene.

“We could change the hashtag and get people to start using a new one,” Tim suggested. “Other companies have done that.”

“And it’s worked,” Andrea noted. “By focusing people on the new hashtag, you draw attention away from the one that was causing problems, and people are less inclined to throw in their own witty insults. It could take a few days for the old hashtag to peter out, though.”

“That sounds like a solution,” Jerry said. “That way we save the contest and let this whole mess blow over.”

“Or we could just end the contest altogether,” Charlene offered.

“Yes, you might remember that’s what JPMorgan did,” Andrea said. “When people hijacked the hashtag to tweet about ‘capitalist pigs,’ they canceled the Q&A.”

“And they came off looking like the arrogant jerks everyone was claiming them to be,” Tim said.

Andrea nodded. “Let’s not jump the gun here. Most of these tweets are positive. They say some lovely things about customers’ experiences with Canadian Jet. If you cancel, you may end up alienating the people who sent in genuine entries and are hoping for those round-trip tickets. It may be better to ignore the bashes and focus on the good publicity you’re getting.”

“And when the press starts calling?” Charlene asked. She worried it was just a matter of time before she would have to start fielding questions.

“You take the high road and say how pleased you are with the positive responses,” Andrea suggested.

“So far I’m not loving any of these options,” Jerry said.

Tim cleared his throat. “We could apologize. It’s worked for us in the past.” Three years back, one of the operations VPs had come up with the idea to make buttons with “We’re sorry” in big black letters and have flight attendants, pilots, and airport staff wear them whenever a flight was delayed or canceled, even if it wasn’t the airline’s fault. Customer response to the tactic had been overwhelmingly positive. It had even helped win the airline an industry customer service award.

“But what exactly are you apologizing for here?” Andrea asked. “You just launched a contest. You didn’t exploit political events like Kenneth Cole did or pull a Home Depot and send out a picture that people thought was racist. It makes sense that those companies said they were sorry, but you haven’t done anything wrong.”

“That’s not what these people think,” Charlene said, pointing to her iPad. She read a few of the latest tweets. “’Arriving a day late to your daughter’s wedding #CanJetLuxury,’ ‘Screwing your workforce #CanJetLuxury.’”

“Enough,” groaned Jerry, holding his head in his hands. The room was silent.

“I’m willing to take a stab at an apology,” Charlene said. “I’m not sure exactly what it’s going to say, but give me an hour.”

8:30am

Charlene stared at the blank Word document on her screen. She typed:

“On behalf of Canadian Jet, I’d like to apologize for the feelings that this contest brought up.”

She deleted it.

“We at Canadian Jet are sorry for disappointing our customers. We’re committed to…”

“That doesn’t work, either,” she said out loud to her computer, pressing the backspace button. She tried a more direct approach.

“We’re sorry that our planes sometimes break, that you think we treat our employees unfairly, and that you don’t like our contest.”

Her assistant poked her head in the door, “I’ve got Carrie Schultz on the line.” This ought to be fun, Charlene thought as she picked up the phone.

Carrie, a blogger for PR News, explained that she was working on a piece about social media gaffes and wondered if Charlene wanted to comment on the crisis in progress.

“I wouldn’t call it a ‘crisis.’ A handful of people poking fun at your business doesn’t constitute a crisis.”

“Are you willing to explain on the record why you’re ignoring the responses? You keep sending out tweets as if everything is going smoothly.”

Charlene quickly pulled up the airline’s Twitter feed and saw that a tweet had gone out at 8:00am: “Keep the responses coming. At this rate, it’s going to take years to judge this contest!” She put her phone on mute and yelled to her assistant to get Tim.

She could hear him running down the hallway. He looked ashen reading the tweet on Charlene’s screen. Charlene pointed to the receiver and mouthed “Carrie Schultz.”

She took the phone off mute. “We’re not ready to comment just yet, Carrie.”

“You better get ready,” she responded. “You’re trending, you know.”

9:00am

“Never mind arrogant. We look completely tone deaf at this point,” said Jerry, his face completely red.

Tim was about to say something when Andrea cut in. “I’m sorry. This is our agency’s fault. We wrote the tweets yesterday and scheduled them to go out throughout the day. We were trying to save some time.”

“Jerry, we’ve turned off the automatic tweets,” Charlene assured him. “But still — we’ve got to figure out what we’re doing. And fast.”

“What about the apology?” Tim asked.

“Andrea was right,” Charlene sighed. “It’s hard to know exactly what we’re apologizing for. The only thing I can think to say is, ‘Sorry we’ve disappointed you in various ways over the past ten years.’”

“What’s wrong with that?” Tim asked. Charlene looked over at him to see if he was joking. He wasn’t smiling.

“We look like chumps, that’s what,” Jerry said, his voice rising.

“So, are we pulling it?” Tim asked. They all looked at Jerry.

“What else have we got for this year?”

“This is our biggest social media campaign,” Charlene replied. “We’ve planned a few other things, but nothing on this scale.” She tried not to look at Andrea. Her agency was as much on the line as Canadian Jet.

“This is not a lost cause,” Andrea said, still utterly composed. “It’s been less than 24 hours. I’m telling you, this thing may die down as quickly as it heated up.”

“I understand why you want to save this, Andrea. But we need to be cautious here,” Charlene said. “Canadian Jet can’t suffer another PR problem.”

Jerry sat down heavily in his chair. “I know we normally take your firm’s advice on these things, Andrea. You’re the experts here, but you’re also the ones who got us into this mess.” He turned to Charlene. “As our spokesperson, I’d like you to make the call.”

Question: Should Canadian Jet cancel the contest?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

Are We Networking, or Is This a Date?

I go out on a lot of “dates” with all people of all ages. Sometimes groups of them — lunch dates, “mind meld” dates, coffee dates. Couldn’t tell you what we’re melding; it’s mostly a brainstorm with more jargon thrown in. But it’s fair to say most of my “dates” are about work. Or so I think.

In this new economy of the personal brand and doing your own thing, everyone is constantly working the room. But it can get confusing as both a single woman and an entrepreneur who works in communications. There are times when I find myself getting drinks or dinner to “talk shop” – but I cannot, for the life of me, figure out: am I on a date?

When you’re in business on your own and shilling your wares around town, the lines between work and play get blurred. Like the time I went out for what I thought were work drinks and the guy planted one on me as I got into a cab. Or the time I wanted, desperately, for a brilliant and handsome mutual friend to assume that our dinner was something more. He didn’t get the memo, and I got cold feet. The confusion swings the other way, too: I have friends who have met professional partners on the dating-app Tinder.

These blurred lines raise a lot of questions, such as: Am I going to this festival to run around half naked and watch burning things or am I here to meet and talk business with a Winklevoss if I can find him? Am I at this happy hour to express my enthusiasm for gin or to meet potential new clients and raise my Klout score? Is this cute entrepreneur flirting with me or just being nice? Should I be giving my elevator pitch? Am I just really bad at signals?

When you’re one on one and the lighting is dim, I couldn’t tell you if we’re talking angel investing as friends or as something more. And how is one supposed to clarify? It would be a lot to presume that this person who wants to “grab drinks sometime” wants to take me on a date. But it looks like a date. It feels like a date. It walks like a date…so is it a date?

If you ask to clarify and it is a date, you’re OK. But if you ask and it’s not, it’s very awkward. Very, very awkward. I don’t want to act unprofessional. But what does “professional” mean any more in world where casual Fridays are more like casual Monday-through-Fridays, and beer carts and whiskey nights pervade office life? You log a lot of hours together, probably in a wall-less office, you’re friends on Facebook. Is making it clear you’d like a date really so bad?

The stigma against office dating may be fading — and in start-up land, many founders are also romantic partners – but there’s one taboo I’d like to keep firmly in place. That’s what I call the “ninja set-up. “Basically, a friend introduces two people under the guise that they will “have a lot to talk about” or “get along.” Then you are being ninja’d into a date. I promise. I’ve tried to find ways to clarify, and once I flat-out asked a guy after we went out a second time (that was definitely a date) about whether or not the first date was a date-date.

He told me he wasn’t sure either.

At least I’m not alone in my confusion. But perhaps the bottom line is this: chemistry is hard to find and shouldn’t be ignored. While we could all analyze body language or texts until we’re blue in the face, maybe we should all just grow up and ask for what we want. You know, like professionals.

Change Your Company with Better HR Analytics

You’re probably a little tired of hearing about Big Data. While you would expect online giants like Amazon and companies like Netflix to be early innovators in the use of data to recommend products or movies, you only care about the answer to one question: what does big data mean for the everyday employee and how can regular businesses extract real value from it?

The good news is that Big Data is making a difference in places and ways you might not expect, particularly in human resources. Companies are analyzing their employee data with workforce analytics to answer a variety of critical questions: Why does one sales person outperform his peers? What is the impact of learning programs on company results? How long does it take for new employees to be productive? Why do certain leaders succeed and others fail?

Black Hills Corp. is one of those companies. A 130-year-old energy conglomerate, Black Hills doubled its workforce to about 2,000 employees after an acquisition. Like many energy companies, a combination of challenges — an aging workforce, the need for specialized skills, and a lengthy timeline for getting employees to full competence — created a significant talent risk. In fact, forecasts showed that, within five years, the firm could lose 8,063 years of experience from its workforce.

To prevent a massive turnover catastrophe, the company used workforce analytics to calculate how many employees would retire per year, the types of workers needed to replace them, and where those new hires were most likely to come from. The result was a workforce planning summit that categorized and prioritized 89 action plans designed to address the potential talent shortage.

For other firms, more effectively using talent data is a key component of an HR transformation, one that seeks to improve the function’s role as a true business partner. In their 2012 book, Transformative HR authors John Boudreau and Ravin Jesuthasan detailed a case study of Ameriprise Financial, a diversified financial services company spun off from American Express in 2005.

When the newly-formed firm began delivering a set of HR activities such as onboarding, training and performance reviews, employee feedback rated the quality of these services as “poor.” Furthermore, Ameriprise Financial had no framework for allocating HR time to talent issues with highest impact.

To improve their HR functions, Ameriprise began to integrate workforce and financial data to align talent investments with business results, and more proactively develop data-driven insights used to predict turnover, reduce new hire failure rates, and manage persistent poor performers. Employee feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with HR transforming from “order taker” to “key business contributor.”

All of this goes back to a prescient observation Murray Gell-Mann, a Nobel physicist, made in an interview with Harvard professor Howard Gardner in the 1970s. He predicted that the trait most valued in 21st century companies would be the capability for synthesizing information. The skill of synthesis is particularly crucial for corporate leaders, given that the decisions they make are fraught with big-picture complexity and the consequences of those decisions are often momentous.

But because leaders sit atop more information sources than most people, there is an inherent risk of information overload. This is compounded by the traditional way in which data is often presented: voluminous spreadsheets containing hundreds of data-points that do little to connect talent metrics to the recipient’s business priorities or decisions.

As such, in the rush to deliver Big Data, organizations should also consider how they can provide better data to their managers to enable higher levels of utilization and faster synthesis of key insights. Consequently, your analytics must be:

Relevant. HR analysts need to apply data to the business issue (a top-down approach), rather than using an unnecessary amount of resources for bottom-up data mining.

Valid. The quality of data is important, along with the way leaders are educated about the credibility of talent metrics.

Compelling. Of the hundreds of HR leaders I speak with each year, one of the most common goals of analytics is to tell a better story with data. HR can’t just present raw numbers and expect the recipient to identify the correct message. Analysts need to understand their audience, create a plot of related storylines, and deliver conclusions that tie together the principal facts.

Transformative. Ultimately, actionable analytics have to change a leader’s behavior. A leader should be able to change his or her thinking and make better, faster decisions as a result of talent data.

There are still obstacles to adopting workforce analytics: Less than half of the global companies use objective data when making workforce decisions, and fewer than 20 percent were satisfied with the ability of their current data management systems to manage talent data, according to an SHL global assessment report published in February. But armed with actionable analytics, leaders and managers have immense opportunities to use talent data in reducing workforce costs, identifying revenue streams, mitigating risks and executing business strategy. As David Crumley, Vice-President of HRIS at Coca-Cola Enterprises, says, “this is where it gets really exciting.”

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

Learn How to Spot Portable Talent

Why Japan’s Talent Wars Now Hinge on Women

Research: Recession Grads May Wind Up Happier in the Long Run

Ten Essential Tips for Hiring Your Next CEO

Just Adding a Chief Data Officer Isn’t Enough

The proliferation of C-suite roles is an indication of the increasing strategic and operational complexity organizations face. Heightened expectations of expertise are also part of the picture — for instance, GE’s recent transition from asking executives to focus on breadth to focus on depth.

One of the newest additions to the C-Suite is the Chief Data Officer. Thomas Redman wrote in October about the increasing value of a CDO and how to know whether such a role might be good for your organization. If you’ve decided to move ahead, then the next step is to effectively build that role into the rest of the top management team. To do so, you need clarity around how the CDO will work with the rest of the top management team as well as incentives that support collaboration across the top executives and senior managers — something that goes beyond equity compensation.

Research shows that you can’t just add a new member to a team without renegotiating the roles and relationships. Members need to know who already knows what, who should know what, and how to coordinate — and that all varies by the particular people in the team, not just their role. For instance, the person who was once the best at analytics may no longer hold that position if a Chief Data Officer is brought in. Brown, Court, and Willmott provide an excellent starter list for the issues to address: Establishing new mind-sets around the value of data; defining a data-analytics strategy; determining what to build, purchase, borrow, or rent; securing analytics expertise; mobilizing resources; and building frontline capabilities.

Brad Peters, CEO of Birst, a business intelligence company, raised the issue of incentives and structure with me in an interview at Saleforce.com’s Dreamforce conference. He said that without changes in incentives, as well as a change in the structure of the C-suite, broad-based roles like Chief Information Officers, Chief Marketing Officers, and Chief Data Officers are hampered in their effectiveness. Alignment with specific business goals is important to all senior executives, of course, but it’s especially true for those who may be in service roles to the business units of the organization.

David Aaker’s helps explain why in his book, Spanning Silos: The New CMO Imperative. Though he was writing about Chief Marketing Officers, his advice is equally valuable here. When incentives are focused on rewarding silo behavior and performance — as so many incentives are — it is a struggle to take advantage of a boundary-spanning executive position. Instead, organizations need cross-silo incentives and initiatives to support behaviors that leverage the skills of the new executive. (Chief Operating and Finance Officers side-step this issue given the broader power-base of their positions.)

The top management team should approach the role clarification and incentive alignment as a negotiation. While it is likely that the entire executive suite would be involved in a decision to bring in a Chief Data Officer, it is important that the process goes beyond involvement. Negotiation, with its norms of agreement to an explicit deal, means that the new role, its responsibilities, and its rewards, are fully integrated into those of the rest of the top management team.

Have this negotiation as part of the new Chief Data Officer on-boarding. Lay out major roles and responsibilities to highlight places where data and other roles intersect given the expertise of the particular people on the top management team. Use Brown, Court, and Willmott’s six tasks of data-focused activities to start developing the issues to have the on the table. Add incentives to the mix by setting goals around the collaborative activities. Morten Hansen argues that you don’t need to overhaul an entire incentive structure — you can focus on special incentives for silo-spanning collaborations.

The whole top management team must collaborate both in fact and incentives. There must be something that rewards cross-silo efforts. To effectively make use of data’s insights, executive teams need more than goodwill and a new hire.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

Is There Hope for Small Firms, the Have-Nots in the World of Big Data?

Big Data’s Biggest Challenge? Convincing People NOT to Trust Their Judgment

Small Businesses Need Big Data, Too

How to Get More Value Out of Your Data Analysts

Five Signs that Your Mentor Is Giving You Bad Advice

Not long ago, I attended the “Forever Green Leadership Gala” in Menlo Park, a fundraiser for The Girl Scouts of Northern California. The event honored two women with impressive accomplishments: Noosheen Hashemi, who earlier in her career spent a decade at Oracle and was instrumental in its 1991 financial turnaround, and who has spent the past decade leading The HAND Foundation; and Cisco Systems‘ Chief Technology & Strategy Officer Padmasree Warrior, one of the most powerful engineers in Silicon Valley, often included in lists of the most powerful women in business, and a persistent advocate for bringing more women into science and technology. The keynote speaker was Sheryl Sandberg, famous both for her role as Facebook COO and for her advice to girls and women to “Lean In.”

There was a lot of discussion of mentoring that night, and the virtues were demonstrated by the accomplishments of three impressive Girl Scouts. We were all taken by Varsha’s story about how her mentors at Girl Scouts guided her as she implemented an astounding Gold Award project: raising the funds for a maternity ward and getting it built in a remote village in India. Maddy told us all about how adults and older girls played key roles in Space Cookies, an award-winning all-girls robotics team with over 80 members from 25 high schools. Most of all, we in the audience were moved by Larissa’s story of how her involvement in a range of Girl Scout programs helped her develop skills, confidence, and a social network that enabled her to make better choices. Larissa had been removed from her parents’ home – both were drug addicts — and placed in foster care. She explained how, by interacting with adult and peer mentors in Girl Scouts, she changed her path and became a good student on track to graduate early from high school and planning to major in social work in college. In turn, Larissa is committed to helping her brothers and sisters lead successful lives and to helping her mother – who has been clean for two years and now lives with her kids again – stay on track. Larissa was especially proud of the role that she now serves as a mentor in Girl Scout programs to other girls who, like her, are at risk.

I was at this inspiring event (about which you can read more here) thanks to my wife Marina Park’s work — she is CEO of the Girl Scouts of Northern California — but couldn’t help making the connection to my own. Huggy Rao and I, as research for our forthcoming book Scaling Up Excellence, have spent the past several years studying what it takes to get constructive beliefs, actions, and skills to spread. The powerful mentoring that these girls have received through Girl Scouts, and that they now provide for other girls, is a version of a process we saw in many of our success stories. If you can “connect people and cascade excellence,” better ways of operating have the best chance of taking hold.

But listening to the comments from the stage that night also made me see a new twist on the “connect and cascade” advice. This time, it was something that Sheryl Sandberg said during the panel conversation after her speech. She told us that, although mentors played a key role in her success, she learned not to believe everything they told her. It was a warning to all present that, even when someone wants to help you, they still can give you bad advice. So it is your responsibility, both for your own good and that of others, to think critically about what you’re told, and at times, choose to ignore it. Sheryl’s own examples were that mentors had advised her not to take the job as an executive at Google and not to take the job as Facebook COO – the very roles that have made her rich and famous.

What does this have to do with scaling? There’s a lesson for those who are struggling to take something that works well in one place and replicate it elsewhere. It just might be that people who are ignoring or rejecting the beliefs and behaviors you are trying to spread are not wrong. They may be doing what Sheryl did: considering your advice and concluding that, while it might have been good for others, it would be bad in their situation. This kind of constructive defiance might even be helpful to you, if what you’re trying to scale is actually very context-dependent, or is a bad idea you’ve got irrational faith in. As Huggy and I like to say, to spread excellence, the first order of business is to make sure that you’ve get some actual excellence to spread!

There is another lesson, of course, for the recipient of advice — and it’s the point Sheryl Sandberg was making. Even if you have the best of mentors, that does not relieve you of the task of figuring out your own best course of action. Mentees have to play an active role in judging the advice they get. With that in mind, and with reference to some applicable research, I’ll offer five signs that maybe you need to think harder about the advice your mentor is giving you:

1. Are you straying from the path that your mentor has taken? Piles of research on “social similarity” or “similarity-attraction” effects suggest that most mentors will have a positive reaction to paths you take that are reminiscent of their own and a negative reaction to paths that clash with their past choices. So if your mentor spent a year working in, say, China as part of his or her career and you are about to turn down a similar opportunity, don’t be surprised if he or she sees it as a mistake.

2. What is in it for them? Will some of your choices benefit your mentor more than others? The answer might be fairly obvious, but still be something that you (and your mentor, who will have imperfect self-awareness) don’t realize is subtly guiding the advice offered. For example, if you work closely today with your mentor, and make his or her life easier and more successful, that usually helpful and objective party might have a hard time giving you the best advice about an opportunity that will put you in a different role. I get annoyed by economists and other behavioral scientists who claim that self-interest is behind every human word and deed – yet there is no denying that it affects every one of us, and more often and more deeply than we realize.

3. Is your appetite for risk drastically different from your mentors? If you are more comfortable with risk than your mentor, he or she may caution you against that crazy new startup or bold new project. I suspect that this was part of the story for Sheryl ; both Google and Facebook were high-risk adventures when she joined. Mismatches also go the other way. As Huggy Rao observes, if your mentor is a skydiver, races motorcycles, and has a history starting risky projects or doing big risky acquisitions – but the very thought of such things keeps you up at night and makes you physically ill – then you might not want advice from that person on taking a risky job or making a risky decision.

4. Do you know more than they do? Just because someone is older and more experienced than you are does not mean that they know more about the particular decision you are making. The more distant they are from the work you do and the business you work in, the more wary you should be. I suspect, for example, that Sheryl understood Facebook’s potential more than older mentors or those who weren’t so heavily steeped in the industry.

5. Do your peers — and those you lead or mentor — know more about you than your mentor does? There is a structural problem with many mentor-mentee relationships that I have implied in past writings: A large body of research shows that, in pecking orders of any kind, the people (and in, fact, animals) who have less power attended more closely to and understand those with more power than the other way around (see here and here). This so called “asymmetry of attention” means that you probably know a lot more about your mentor (who is likely more powerful than you) than your mentor knows about you. Consider some implications. You may be overestimating how well your mentor knows and understands you as a result (and thus putting too much faith in his or her advice). Such asymmetry also suggests that your peers, our better yet, the people who you lead and mentor, may give you the best advice. Indeed, I have argued (going back for some 30 years) that reverse mentoring is underappreciated and underused by both organizations and individuals.

Of course, I am not implying that your default posture toward a mentor’s advice should be skepticism and rejection. As those Girl Scouts’ stories demonstrated, when someone knows you and wants to see you succeed, anything they think you should know is worth listening to — and some of it may be essential to your subsequent success and happiness. But if you want to get the most out of mentoring, don’t take it as marching orders. For you and your mentor, the greatest success comes when you decide wisely for yourself.

Wage Inequality Rises in Europe as Workplaces Become Americanized

As European countries have tried to restore competitiveness, the decline of unions and the easing of worker protections such as restrictions on dismissals have helped “Americanize” workplaces there, says The New York Times. One consequence has been an increase in wage disparity. In Germany, for example, the richest 10% of people earned 26% of the nation’s income in 1991; by 2010 they took in 31%. Over the same period, the proportion of the nation’s income earned by the bottom half of the population fell from 22% to 17%.

Teslas Catch Fire Less Often than Gas-Powered Cars

Tesla has gotten significant negative press coverage because of accidents involving fires. In Washington and Tennessee, fires resulted after cars ran over debris on the road that pierced the battery compartment. These incidents have caused the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to open a formal investigation into the safety of the Tesla Model S electric car. (A third fire happened in Mexico after a driver drove through a wall and hit a tree.)

Tesla’s stock has already rebounded, after an initial plunge, after a German safety inquiry said it found no mechanical defects with the $70,000 cars. But consumers may be tougher to win back than investors. The images of burning Teslas will be hard to overcome in the minds of potential buyers.

Tesla needs to reframe the discussion away from the safety of Tesla alone and shift the conversation to a comparison between the safety of gasoline-powered cars and the subcategory of high-powered electric cars for which Tesla is the exemplar brand — and, in fact, the only brand.

Tesla should take a page out of political contests and draw attention to the negatives of their competitors — in this case, gasoline-powered cars. The statistics are powerful. Last year there were 172,000 gasoline-powered car fires, a little-known fact. Given that some 240 million cars are registered, that means a fire for every 1,300 or 1,400 cars on the road. Compare that to three fires from some 20,000 Tesla cars. The fire incidents are over four times as great in gasoline-powered cars.

The death statistics are even more compelling evidence that gasoline-powered cars are unsafe compared with Tesla cars. Since the Model S went into production in the middle of last year, there have been over 400 deaths and 1,200 serious injuries in the United States alone due to gasoline car fires, compared to zero deaths and zero injuries due to Tesla fires anywhere in the world.

The surge in publicity over the Tesla fires could provide an opportunity for Elon Musk’s company to make the car fire safety issue more important in people’s minds and to communicate the fire risks of gasoline-powered cars. For some drivers, a more visible fire risk might create a reason for a car buyer to say no to the gasoline-powered subcategory. It could also provide the Tesla brand with an advantage over other battery-powered car brands.

In taking this opportunity, it is important to recognize that Tesla is managing a subcategory rather than a brand. True growth nearly always happens at the level of subcategory competition rather than the “my brand is better than your brand” level, because is where market structure changes occur, as I’ve discussed elsewhere in more detail.

To take the fight to the gasoline-powered subcategory, though, there are two other assets that Tesla should be sure to bring into play. First, they should continue to deploy Elon Musk to tell their story. He is charismatic, credible, and a classic innovator. Second, in part through social media, Tesla needs to engage its passionate fan base, which goes way beyond its 20,000 car owners.

Few brands, particularly those under attack, have such assets that they can bring to bear.

December 10, 2013

Mary Barra and the New General Motors

It is now official. Girls like cars. And car companies know how to be driven by women.

The appointment of Mary Barra as CEO-to-be of General Motors is a signal to car-lovers everywhere that the company is serious about its products and vehicle innovation. An engineer with a diemaker father who worked in a Pontiac plant, Barra is a 33-year company veteran. In her current job as executive vice president of global product development, she is responsible for the lineup of the future and the components that will make cars greener, safer, more user-friendly. The centrality of innovation to the future — electric cars, hybrids, self-driving cars, and beyond — makes her experience pivotal. This is a new GM.

Barra began her career at the old GM as a young student engineer. Around the same time, I first visited GM executive floors and factory floors throughout Michigan as a young professor and consultant. My book Men and Women of the Corporation, which looked inside an anonymous industrial corporation (not GM) had recently been published, and I was in demand to explain to executives why their corporate structures and cultures set some people on a path to success (generally men who resembled the other men in power) and systematically ignored others equally talented.

I came to know most of the significant large companies of that time. The old GM was the most macho and woman-unfriendly of them all.

This situation was untenable. American manufacturing companies were falling behind because of hidebound, privilege-laden bureaucracies that squashed new ideas, failed to listen to voices from below, behaved arrogantly toward customers, and generally stifled innovation. GM was trying to change its culture (and I credited the company for that in my book The Change Masters). But it was too insular to make much progress. GM’s way of change was to leave the mainstream establishment untouched while setting up a separate unit to try to do it all differently – NUMMI, a joint venture with Toyota in California, or the now-defunct innovative Saturn subsidiary.

Meanwhile, GM was nurturing female talent in its classrooms. Little did any of us know then, but two of the world’s most powerful future CEOs – the future heads of Fortune 20 companies — were getting their engineering training at General Motors Institute — Ginni Rometty, CEO of IBM, and Mary Barra.

“What’s good for General Motors is good for America” has been derided endlessly as a joke of a slogan from the military-industrial complex – but this time I sincerely mean it.

Mary Barra is good for GM first and foremost because she’s an engineer who cares about cars. She is good for GM because she reflects the new culture of teamwork and collaboration. She knows the people side as the former head of HR. She is a clearly a team player with the support of her peers, such as CFO Dan Ammann, promoted to president working with Barra. In July, Barra and Amman came together to a high-level executive program at Harvard Business School, Leading the Global Company, which I taught with several colleagues. In both of them I saw the listening-learning embrace-differences style of leaders of the future, and no traces of the arrogant know-it-all attitude from GM’s Detroit-centric days.

It’s good for America for GM to have a CEO who is a car and truck person and who also happens to be a woman. It’s good for America to inspire more students to find opportunities in vehicle engineering rather than financial engineering. It’s good for America to encourage young women to study STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math), and then to seek careers in manufacturing industries that lose their men’s club taint. The nation desperately needs more STEM graduates, and the pool must be enlarged to include women.

Barra has been named CEO because she earned it, by demonstrating technical and managerial competence over 33 years. I’ll bet she doesn’t want to be a symbol, that she just wants to do her job and grow the company to which she has dedicated her life. But like it or not, as the head of one of the world’s largest auto companies, her very presence sends messages that will reverberate around the world. (For Saudi Arabia, for example, the message is that women belong in the driver’s seat.)

The idea of a woman CEO of an auto company will reverberate at home too. It means one more barrier broken, one more sign that women can be and do anything. And for all the parents who are wondering what gifts to get their daughters for the holidays, I say the more toy cars, the better. Start early, and go far. It works. Barra is one more proof that girls, too, like cars.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers