Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1495

December 17, 2013

Four Keys to Thinking About the Future

A publishing company has discovered that one of its well-known authors has plagiarized. The publisher has pulled the title. But does the publisher’s responsibility end there? Does one disclose the transgression to the public? Or to the author’s university employer? Or insist that the author do so him/herself?

Dilemmas are situations that require us to make a choice between equally unfavorable options.

I recall an instance as President and CEO of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) when I was informed by my security chief — he and I both held top secret security clearances — that one of our journalists had once worked undercover for a hostile intelligence service. Mind you, while the discovery was recent, this transgression had occurred years ago. The intelligence service (and regime) had since ceased to exist. In the meantime, the journalist in question had become a respected colleague. What to do with the fellow? Dismiss him? On what grounds? And to what effect inside the company?

Confronting ambiguity is one of the issues that came up time and again in a symposium I had the pleasure of convening recently with the Harvard Business Review and the Sidney Harman Academy for Polymathic Study at the University of Southern California. The day-long symposium, called “The Next Big Thing: a Historical Approach to Thinking about the Future,” included a small, formidable mix of business leaders, technologists, historians, economists, defense experts, pollsters, and philosophers.

We all think about the future, but my first conclusion from this London gathering was that some people are better equipped than others to see it. Reflecting on the discussion, my own conclusion is that, if you want to become more prescient, you should do four things:

1. Enhance Your Power of Observation. For starters, be empirical and always be sure you’re working with the fullest data set possible when making judgments and discerning trends. Careful listening, a lost art in today’s culture of certitude and compulsive pontificating, can help us distinguish the signal from the noise.

In fact, read Nate Silver’s 2012 book, The Signal and the Noise : Why Most Predictions Fail – but Some Don’t. Also see psychologist Maria Konnikova’s 2013 Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes. Drawing on recent research from psychology and neuroscience, Konnikova presents ways to sharpen one’s methods of observation and deductive reasoning. I also recommend the essay “The Power of Patience” in the current issue of Harvard Magazine. Art historian Jennifer L. Roberts has her students spend what appears at first to be an excruciatingly long period — three hours! — with a painting in a gallery. “It is commonly assumed,” observes Roberts, “that vision is immediate. … But what students learn in a visceral way in this assignment is that in any work of art there are details and orders and relationships that take time to perceive.” Ditto in any shifting business environment.

2. Appreciate the Value of Being (a Little) Asocial. I had a colleague once, a distinguished China scholar, who eschewed conferences and professional gatherings. His logic was simple. He was convinced that this otherwise entirely pleasant socializing and socialization led invariably to a kind of groupthink among the community of experts. “Thinking outside the box,” is one of the most well-worn clichés in any business or creative endeavor. We all prize it. Yet how do you actually do it, when life and livelihood generally depend on operating inside a box?

I’m convinced that a company culture that encourages curiosity is vitally important. Read the essay by Rutgers historian James Delbourgo in The Chronicle of Higher Education on “Triumph of the Strange” and Brian Dillon’s volume of essays titled Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing. Curiosity keeps us learning and helps us, like the virtue of patience, to see the hidden, or understand the unexplained.

3. Study History. Do this not because history repeats itself, but because history often rhymes, as Mark Twain put it. The rhymes may be about social patterns, the impact of technology, or how nations tend to adapt. Charles Emmerson of Chatham House was a member of our roundtable. He’s the author of 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War, a recent book that depicts a civilization a century ago that was interconnected and fragmented, cosmopolitan and chauvinistic, prosperous, decadent, and in danger of decline. It sounds similar to the situation of the West today.

I think you study history to study human nature, the human condition, and human behavior. This is the realm of patterns, but also — frustratingly and fascinatingly — of infinite complexity and unpredictability. Apart from the intrinsic beauty, power, and simple enjoyment, it’s why reading great fiction is to be commended. HBR writers have more than once made the business case for reading literature. Training in emotional intelligence is life-long work, and most of us need as many tutors as possible.

4. Learn to Deal with Ambiguity. A banker in our group emphasized the importance of this. Whether it’s nature or nurture, most of us seem hard-wired to sort the world into simple binary choices. Alas, there’s often lots of grey out there. I’m not sure what the publisher ended up doing in the case I cited at the outset. Nor am I at liberty to reveal my own decision regarding that former intelligence officer. But those are matters of the past anyway. Thinking about the future, here’s a final reading tip. It’s the 1992 novel Einstein’s Dreams by MIT physicist Alan Lightman. I’m fond of this passage:

In this world, time has three dimensions, like space. Just as an object may move in three perpendicular directions, corresponding to horizontal, vertical, and longitudinal, so an object may participate in three perpendicular futures. Each future moves in a different direction of time. Each future is real. At every point of decision, the world splits into three worlds, each with the same people, but different fates for those people. In time, there are an infinity of worlds.

Consciously attempt to act on these four pieces of advice and I think you can only get better at anticipating the big things (and small things) that will come next.

Of course, the wisest among us will always hedge our forecasts with qualifiers such as “will likely” or “is apt to.” Life is seldom linear and best estimates frequently become undermined by those eternal “unknown unknowns.” But don’t let them stop you from preparing for an uncertain future by learning more from the past and present. Think long, think deep, think laterally — and brace yourself. 2014 is nearly upon us.

What Boards Can Do About Brain Drain

Not only are individual companies and industries battling for talent, but countries are, too. In the global competition for top talent, emigration of highly skilled workers —brain drain — can result in an especially pernicious drag on the source nations’ talent pools. Many countries are susceptible to flights of talent and experience its deleterious effects.

We wanted to take a deeper look at this phenomenon, so we chose a country that has been experiencing substantial losses of highly skilled talent for many decades: New Zealand. In fact, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that almost a quarter (24.2%) of all New Zealanders with university-level educations have emigrated. Among OECD nations, only Ireland has suffered as much brain drain.

Consider how the talent exodus is playing out New Zealand: between 2012 and 2013, the country’s researcher headcount (per million of the population) dropped by almost 11% and its ranking in the Global Innovation Index dropped four slots. Given that innovation can be a highly influential driver of competitive advantage, how can New Zealand build or maintain any advantage while losing so many of its best and brightest?

As labor markets continue to open up and nations and the corporations they house chase ways to stem the talent drain and retain their skilled workers, we wanted to know how those at the highest level of industry — corporate directors — viewed the problem and what, if anything, they were doing about it.

Global Disconnect

In 2012, we surveyed (in partnership with WomenCorporateDirectors and Heidrick and Struggles) more than 1,000 board members in 59 countries including New Zealand. To facilitate a deeper dive into corporate governance in New Zealand, we administered the survey to a second wave of New Zealand directors between December 2012 and March 2013 to increase the sample size. We analyzed the data along several dimensions and for this analysis compared a breakout of New Zealand directors with their global counterparts.

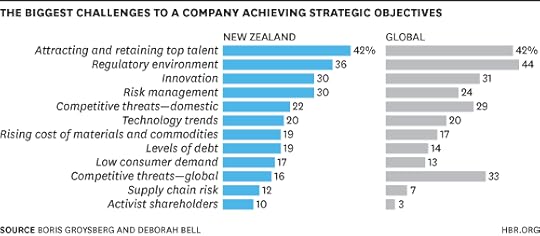

Our analysis found that “attracting and retaining top talent” was their number one strategic concern as it was for directors across the globe. “Innovation” and the “regulatory environment” were top concerns for both groups, but in what seems to be a strategic non sequitur New Zealand directors were substantially less concerned about global competitive threats than directors globally. We found this surprising given that brain drain leaves the flight country vulnerable to competitive threats.

One other difference of note: although risk management was somewhat more of a concern for New Zealand than global directors, a substantially smaller percentage of New Zealand board members (13% versus 29% globally) indicated that their companies had a Chief Risk Officer in place.

We also asked the directors to assess their companies’ performance on talent management by evaluating the following nine practices:

attracting top talent

hiring top talent

assessing talent

developing talent

rewarding talent

retaining talent

firing

aligning talent strategy with business strategy

leveraging diversity in company’s workforce

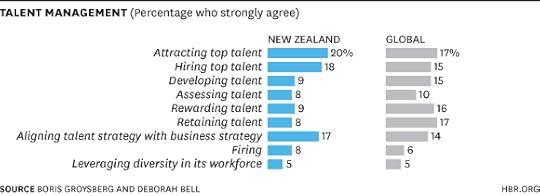

To gain advantage in the war for talent, companies should execute superbly on each of these dimensions, but when talent is fleeing outstanding execution is essential. Therefore, we were not interested in uncovering the percentage of directors who thought their companies were doing an adequate job but rather the number who could say their companies were doing a great job — those who “strongly agreed” their companies were performing each practice effectively.

Our analysis revealed very low scores for both New Zealand and global companies. In fact, not more than 20% in either group could say their companies were doing a great job on any one practice, and, further, the percentage of New Zealand directors who described their companies’ talent management as “great” was mired in the single digits for six out of the nine practices.

Although the New Zealand and global scores were similar for most practices, there were two with a noteworthy difference: retaining and rewarding talent. When we consider these differences within the context of the ongoing brain drain from New Zealand, they make sense. And although many factors influence the rate of talent flight, the lure of higher paying jobs and greater earning potential outside of the home country is a very important factor and has played a role in the emigration from New Zealand of its highly skilled workers.

Talent Trouble at the Board Level

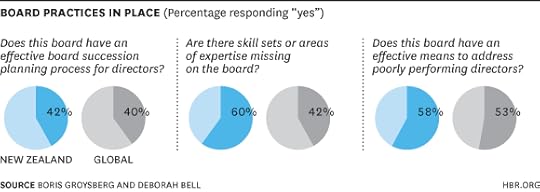

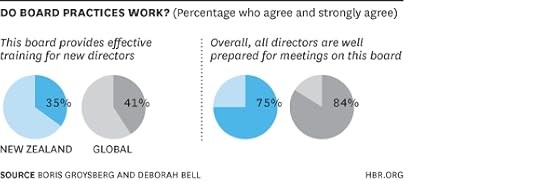

In addition to uncovering a considerable deficit of outstanding talent management practice in New Zealand companies, our analysis also revealed that New Zealand boards are not doing a great job managing their own talent. Fifty-eight percent said they did not have an effective board succession planning process for directors, fully 60% said there were skills missing on their boards, 42% said their board did not have an effective means to address poorly performing directors, 25% could not say that all board members were well prepared for meetings, and only 35% agreed that their boards provided effective training for new directors

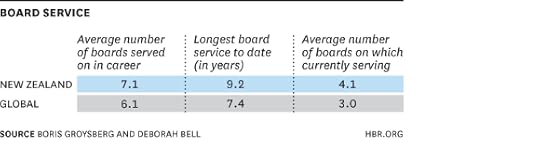

We also discovered that, on average, New Zealand directors served on more boards during their careers, sat on more boards concurrently and served for longer periods than their global counterparts. Although more research is needed to better understand the factors influencing board service, these differences might suggest that, in addition to closed networks, New Zealand boards are drawing from a smaller talent pool because of brain drain, that is, many New Zealanders who would be qualified to be directors have left the country.

In order to keep their companies viable and competitive, our research revealed that corporate directors in New Zealand, like their global counterparts, were most concerned about attracting and retaining top talent. Yet, as our data made plain, directors said their companies were not doing a great job on retention. Although the global scores for executing well on retention were very low (17%), they did not even reach double digits in New Zealand (8%), a country blighted by talent flight.

If one of the keys to successful hiring is successful retention, the key to implementing great hiring and retention practices is great corporate governance. But it is unlikely boards will be able to improve their companies’ talent management practices until they fix their own. As our analysis uncovered, boards need to improve many of their key talent practices, e.g., succession planning, identifying and appointing directors with the skills their boards need, effectively onboarding and training new directors, and managing board dynamics.

Change starts at the top and boards need to be the exemplars for their organizations by providing leadership, stability and effectively executing their own talent management practices. It seems that some boards may, unfortunately, not be offering solutions within the realm of their gigantic talent management problems, but rather, contributing to them.

Methodology

We surveyed more than 1,000 board members in 59 countries. Groysberg and Bell administered the survey to a second wave of New Zealand directors between December 2012 and March 2013. We analyzed the data along several dimensions including geography and specifically for this analysis we did a New Zealand and Global breakout.

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

The American Way of Hiring Is Making Long-Term Unemployment Worse

We Can Now Automate Hiring. Is that Good?

Learn How to Spot Portable Talent

Why Japan’s Talent Wars Now Hinge on Women

The Danger of Turning Cynical About Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is losing its luster, at least among elite opinion-makers. An increasing number of critiques have been mounted in publications as diverse as The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, and Wired (to name only a few) based on charges of sexism, conspicuous consumption, inequality, and an attitude toward government and social problems ranging from naivete to disdain. Reports of an entrepreneur trying to teach a homeless man to code and, most recently, of one ranting publicly against the homeless haven’t helped. Perhaps most damning to entrepreneurs, inclined to pride themselves on what they produce, is the charge that many of the products Silicon Valley has been churning out are trivial.

Most of these critiques have merit, particularly those based on gender. But the economic case against startups is prone to overreach and represents a dangerous kind of cynicism. Tech entrepreneurs are not merely akin to Wall Street bankers, a younger, less formal set of oligarchs in waiting. Startups are an engine of prosperity, albeit a highly imperfect one. And if America’s media and cultural elite choose scorn over engagement, the whole economy will suffer.

Perhaps the most complete case for the wave of media disillusionment with startups is a September article in The New Republic by Noreen Malone who asks whether “tech entrepreneurs [are] replacing Wall Streeters as the rich bad guys in the popular imagination.” While noting that this doesn’t seem to be the case with respect to the public — both the computer and internet industries poll favorably — she documents at length the rise of “tech hate” among journalists and other commentators, including HBR contributor Umair Haque:

“Tech is something like the new Wall St. Mostly white mostly dudes getting rich by making stuff of limited social purpose and impact,” economist Umair Haque argued on Twitter. Tech-world denizen Jesper Andersen tweeted a similar sentiment: “Change ‘startup’ to ‘hedge fund,’ ‘ecstasy’ to ‘cocaine’, and ‘douche-bag’ to ‘douche bag’ and you too can see SF is just another Wall St.” Or this, from Mother Jones’ Clara Jeffrey: “I saw the best minds of my generation building apps to send sexts and brag about fitness and avoid the poors.”

By this logic, there’s no reason to applaud the growing number of graduates from top universities opting for jobs in startups and tech rather than finance. This equivalence is too cynical by half.

Though venture capital funds account for only about 0.2% of U.S. GDP, according to Harvard Business School professor Josh Lerner, venture-backed companies made up more than 11% of public firms as of 2011, with a total market value of $25.9 trillion. Moreover, those public firms employed 6% of the public-company workforce. Compared to the small amount we invest in them, startups have an outsized impact on the U.S. economy and on employment.

Of course, Wall Street also looks pretty good when dollars are considered a proxy for value created; a growing line of research argues that the increasing financialization of the economy is holding back overall economic growth. Could the same be true of the entrepreneurial sector? Quite the contrary. Though economic growth remains a highly uncertain area of study, virtually all economists agree that technological innovation plays a central role.

Tech startups play a critical role both in driving technological innovation forward and in bringing it to market. As Lerner writes, “Venture funding does have a strong positive impact on innovation. On average, a dollar of venture capital appears to be three to four times more potent in stimulating patenting than a dollar of traditional corporate R&D.” And the level of entrepreneurship predicts economic growth at a city level, even after accounting for numerous confounding variables.

How does all this square with the intuition that products and services like Snapchat aren’t the most valuable use of the tech sector’s time?

Actually, one line of thinking suggests that typical economic indicators drastically underestimate the social value of cheap internet-enabled entertainment. But the simplest answer is that while consumer-facing apps get most of the press, they’re only one piece of the startup ecosystem. Last quarter, within the dominant “Internet” category, the most venture capital deals were done in the areas of business intelligence and analytics, followed by advertising, HR and workforce management, and customer relationship management — all ways of using the Internet to make other businesses more efficient. By contrast, only 2% of deals went to social companies. Even in the mobile category, the number of deals in photo startups trailed behind CRM, analytics, and payments. And while Internet and mobile have together accounted for the bulk of VC deals in recent quarters, healthcare still represents a substantial chunk — 13% of deals and 16% of dollars in Q3.

The positive economic impact of the startup sector in no way diminishes the merit of other critiques against it, but recommends an approach that seeks to improve the industry rather than discredit it. Addressing Silicon Valley’s gender and class problems becomes even more urgent when one realizes the outsized role that the ecosystem plays in defining our economic lives.

Building useful products may not be the same thing as saving the world, but neither is it the same as doing nothing. Let’s not lose sight of the difference.

The Three Pillars of a Teaming Culture

Building the right culture in an era of fast-paced teaming, when people work on a shifting mix of projects with a shifting mix of partners, might sound challenging – if not impossible. But, in my experience, in the most innovative companies, teaming is the culture.

Teaming is about identifying essential collaborators and quickly getting up to speed on what they know so you can work together to get things done. This more flexible teamwork (in contrast to stable teams) is on the rise in many industries because the work – be it patient care, product development, customized software, or strategic decision-making – increasingly presents complicated interdependencies that have to be managed on the fly. The time between an issue arising and when it must be resolved is shrinking fast. Stepping back to select, build, and prepare the ideal team to handle fast-moving issues is not always practical. So teaming is here to stay.

Today’s leaders must therefore build a culture where teaming is expected and begins to feel natural, and this starts with helping everyone to become curious, passionate, and empathic.

Curiosity drives people to find out what others know, what they bring to the table, what they can add. Passion fuels enthusiasm and effort. It makes people care enough to stretch, to go all out. Empathy is the ability to see another’s perspective, which is absolutely critical to effective collaboration under pressure.

The leader’s task is to model these behaviors. When leaders ask genuine questions and listen intently to the responses, display deep enthusiasm for achieving team goals, and show they’re attuned to everyone’s diverse perspectives no matter their position in the hierarchy, curiosity, passion and empathy start to take root in a culture. When you join an unfamiliar team or start a challenging new project, self-protection is a natural instinct. It’s not possible to look good or be right all the time when collaborating on an endeavor with uncertain outcomes.But when you’re concerned about yourself, you tend to be less interested in others, less passionate about your shared cause, and unable to understand different points of view. So it takes conscious work to shift the culture.

Consider the case of Julie Morath, a pioneer in launching an ambitious patient safety initiative at Children’s Hospital and Clinics in Minnesota, long before such efforts became widespread in the industry. To get employee attention, she gave speeches about patient safety and met one-on-one with opinion leaders throughout the organization. But still, staff resisted the change effort, confident that the hospital didn’t really have a problem. Instead of using her position to argue her position more forcefully, Morath responded to the pushback with questions. “What was your own experience this week, in the units, with your patients?” she asked thoughtfully. “Was everything as safe as you would like it to have been?”

This simple inquiry transformed engagement, and started to shift the organization’s culture to one in which people started teaming up to improve safety. Morath’s simple questions made the staff realize that most of them had been at the center of a health care situation where something did not go well and the hospital could indeed be doing better. She went on to lead as many as 18 focus groups to allow people to air concerns and ideas. As everyone began to discuss the incidents they’d experienced, it became clear that their experiences weren’t unique or idiosyncratic; many of them had similar stories.

In short, Morath’s display of curiosity helped others deepen their own understanding of the organization’s processes and results. She was passionate about patient safety, and her passion was infectious. Finally, her empathy was unmistakable, extending not just to the patients whose lives would be saved by higher quality care but also to the employees who needed to team up under pressure day in and day out.

Culture That Drives Performance

An HBR Insight Center

Three Steps to a High-Performance Culture

If You’re Going to Change Your Culture, Do It Quickly

As a Leader, Create a Culture of Sponsorship

Ferguson’s Formula

10 Sustainable Business Stories Too Important to Miss

Somehow it’s already year-end, a time to look back and try to make sense of what’s happened. Creating any “top” list of stories from 12 months is nearly impossible. But as I’ve done for the last 4 years, I’ll attempt to summarize some of the latest stories about the big environmental and social pressures on business, and how some innovative companies are dealing with them.

This year, like recent years, saw some continuation of big trends: with a few exceptions, the international policy community keeps failing to come to a meaningful agreement on climate change; carbon emissions just keep rising; transparency is increasingly unavoidable and keeps gaining technology-enabled traction; pressure from big companies on their suppliers keeps going up.

So what’s really new this year? Let’s dive in.

The Big Picture

1. The science of climate change gets clearer: the IPCC lowers our carbon “budget.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its wonky, but readable, Summary for Policymakers (a precursor to the full 2014 report). The report expresses “near certainty” that humans are causing climate change and calculates how much more carbon we can “safely” put in the atmosphere and hold to the 2-degree warming threshold that the world’s leaders have agreed to (and some scientists are suggesting that even the 2-degree threshold is too high).

The short story is that we have less room than before. PwC’s annual Low Carbon Economy Index report concluded that we must lower global carbon intensity (the amount of carbon produced for every dollar of GDP) by 6% per year until 2100, a percentage point lower than last year’s report recommended. On the upside, similar calculations from WWF and McKinsey suggests that this pace of change –they endorse a 3% reduction in absolute emissions per year through 2020 – will actually be very profitable.

2. The reality of climate change and pollution get scarier: Australian heat, Philippine devastation, and Chinese air pollution all break records.

The models and carbon budgets aside, the weather this year got even more extreme, helping make the case for action in a more visceral way. In January, Australia’s meteorologists had to add new colors to weather maps to deal with temperatures ranging up to 54 degrees Celsius (129 degrees Fahrenheit). And in November, after the Philippines faced the most powerful storm ever recorded to hit land, some climatologists suggested we add a “Category 6” to the top end of the storm scale.

While it’s impossible to tie any single weather event to climate change, the complicated correlation got clearer this year. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration concluded that “high temperatures, such as those experienced in the U.S. in 2012, are now likely to occur four times as frequently due to human-induced climate change.”

In parallel, China’s air became, at times, dangerous and unbreathable. Several cities experienced days with small-particle air pollution running 25 to 40 times higher than the World Health Organization’s recommended limit. This may seem like a regional story, but it has global ramifications for manufacturing, consumer goods, the energy industry, and much more. The world’s most populous country is taking increasingly drastic action, such as slashing Beijing’s new sales quota for cars by 40%.

3. The clean tech markets keep growing fast: three of the world’s biggest economies — the U.S., Germany, and Walmart — add lots more renewable energy.

In October, 99% of the new energy added to the grid in the U.S. came from renewables (solar alone was 72%). Germany keeps breaking its own records, with wind and solar providing 59% of the country’s energy one sunny day in October. And America’s wind power has quadrupled over the last 5 years; wind is now generating enough electricity to power the state of Georgia.

In addition, electric and hybrid cars are about 4% of US auto sales now, a doubling of market share in the last couple of years. Companies are increasing investments as well. Walmart, already the largest private sector buyer of solar power in the US (with more solar capacity than 38 U.S. states), committed to a 600% increase in renewable energy by 2020.

4. Deep concerns about labor conditions, wages, and equity take root: From tragedies in Bangladeshi apparel factories to minimum wages in the U.S.

Travesties like the death of more than 1100 workers at the Rana Plaza apparel factory in Bangladesh are increasingly unacceptable to the buying public. And it’s getting harder to hide how connected we all are to these workers. When the news hit about the loss of life, front pages around the world included the names of major brands that depended on the factory to make their goods. A startup called Labor Voices is now collecting information on working conditions in Bangladesh and elsewhere in a shockingly simple way: by giving workers a number to call from their cell phones, which everybody now has.

European companies are doing more than U.S. peers, at least publicly, to commit to higher safety standards. Swedish retailer H&M recently said it would pay a “living wage” to 850,000 workers in its supply chain by 2018 – a somewhat vague, but important announcement. And to be fair, while U.S. companies haven’t been as clear, Walmart has contracted with Labor Voices to gather data on its 300+ Bangladeshi suppliers and subcontractors.

On the other side of the ocean, though, Walmart, McDonald’s, and many others are facing increasing challenges about minimum wages. Watch this space, as it seems unlikely that this debate will go away.

5. Food and food waste gets more attention, debate, and innovation: Can cows save the world, or should we make meat in labs?

The level of concern about how we’re going to feed 9 billion people by 2050 is rising. Food waste also got more attention: a UN report estimated that the world throws out $750 billion worth of food annually. Food is too big a topic to summarize, but a few stories grabbed my eye this year. Fenugreen, a smart startup that won the Sustainable Brands Innovation Open in June, sells sheets of paper made with natural ingredients that fight food decay – they can keep fruit and veggies from going bad 2 to 4 times longer than they would last normally.

On a different front, Biologist Allen Savory made a splash with a much viewed TED talk about how grazing cattle in a way that fertilizes land and sequesters carbon can fight desertification and climate change. His theory is under attack, at least to the extent that his method could make a significant dent in our climate problem. Wherever the science on this ends up, it’s an important discussion that brings more focus to systems thinking and to the nexus of food, energy, and water. Finally, a quirky, totally different meat story was fascinating. Billionaires Bill Gates and Sergey Brin are funding experiments to grow meat in labs, a process that – once people get past any “ick” factor – could greatly reduce the footprint of producing meat-based protein.

What Companies Are Doing

6. (Some) businesses get off the sidelines in the climate policy fight: Hundreds of companies sign onto the Climate Declaration.

Started by the NGO Ceres, as part of its Business for Innovative Climate & Energy Policy (BICEP) initiative, the Climate Declaration is a broad statement of intent that acting on climate will be good for our economy and society. A large range of leading companies have signed on including Diageo, ebay, EMC, Gap, GM, IKEA, Intel, Microsoft, Nestle, Nike, Portland Trailblazers, Starbucks, Swiss Re, Unilever, and many more. The Declaration itself is directional and not as specific as what Ceres and a subset of these signatories advocate for as part of BICEP’s work (like pricing carbon and aggressive energy efficiency programs). But it’s a very good start and demonstrates that the business community is not against tackling climate change.

In related news, Accenture produced a fascinating survey of 1000 CEOs around the world, in which a surprising 83% agreed that government should play a critical role in enabling the private sector to advance sustainability. And 31% even supported “intervention through taxation.” In a world where business generally fights all regulations and government interventions, it’s astonishing that one third of global CEOs basically said, “tax us.”

7. Companies are aiming higher, for themselves and their partners: Dell, Coca-Cola, Lego, and many more set very aggressive environmental and social goals.

Goals are not the same as outcomes but they matter a lot – they set the bar within sectors, driving competition and performance. As part of its 2020 Legacy of Good Plan, Dell said that it’s aiming to get a 10-fold multiple of good (reduced footprint, for example) from its technologies versus the impacts of making them (mimicking BT’s earlier 3:1 “Net Good” goal). More specifically, the company pledged to reduce its greenhouse gases by 50% and product energy intensity by 80%.

Coca-Cola launched its own 2020 goals including reducing value chain carbon emissions by 25% (per drink), recovering 75% of bottles and cans, and replenishing 100% of the water the company uses. And Lego just announced its intention to use 100% renewable energy by 2016. A few companies have already made incredible progress, including Diageo, which, I reported earlier this year, cut its North American GHG emissions by nearly 80%.

In fact, 75% of the world’s largest companies now have multiple environmental and social goals in place (see my new website, www.pivotgoals.com, a searchable database of 2500 environmental and social goals set by the world’s largest companies). In addition, my research shows that more than 50 of the top 200 companies have even set carbon goals in line with PwC’s 6% per year reduction recommendation.

A few companies have begun to extend their goals to their suppliers, a form of what I’m calling “de facto regulation.” Walmart is phasing out 10 toxic chemicals in the products on its shelves, and HP set a carbon reduction goal of 20% for its supply chain.

8. Sustainable companies are winning the talent wars: Unilever ranks 3rd in LinkedIn’s list of in-demand employers.

Just consider LinkedIn’s top 20 most in demand companies (in order): Google, Apple, Unilever, P&G, Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, PepsiCo, Shell, McKinsey, Nestlé, Johnson & Johnson, BP, GE, Nike, Pfizer, Disney, Coca-Cola, Chevron, and L’Oréal. The tech companies make sense given the platform (and they’re cool brands). But the rest are perennially in-demand employers, such as big consumer brands and top destinations for MBAs (McKinsey) and engineers (Shell).

But what’s surprising is Unilever’s rank — for a company not nearly as well known as the others, it came in just behind two of the hottest, most valuable companies in the world, and ahead of much better known brands like Disney, Nike, and Coca-Cola. Executives at Unilever credit their ranking to the company’s known leadership on sustainability. It’s hard to argue the point.

9. Systems innovation starts to take root: NIKE, NASA, USAID, and the Department of State create LAUNCH.

LAUNCH is an initiative to identify and accelerate innovations that help solve global problems with water, health, energy, waste, and systems. This program is new so it’s unclear what the impact will be, but it’s an interesting and indicative story for two reasons. First, look at the partners — what a weird, wonderful mix of business, government, and scientific organizations. Second, the goal is really systems change, and if we’re going to solve the mega challenges in our midst, we need to work across value chains and traditional lines.

10. Better tools for companies to assess “materiality” get closer: SASB releases its first sustainability accounting standards.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board has been plugging away, drawing together executives from the world’s largest companies to develop the right sets of questions – specific to each sector – that will help leaders identify which environmental and social issues are really material to their business. We’re very early in this journey, but SASB produced the first set of guidelines for one sector (health care). Watch this space.

2014 and Beyond

Will the divestment movement continue to gather steam and put significant pressure, either financial (unlikely) or moral (much more intriguing), on fossil fuel companies?

Will all the talk about building a circular economy gain mainstream acceptance?

Will we get better at valuing natural capital (and will companies and markets care)? It certainly garnered lots of attention this year, with new estimates of the damage the global economy does to natural assets (trillions), new tools to measure natural capital, and an important new book from former Goldman partner and CEO of The Nature Conservancy, Mark Tercek.

Can challenges to our consumption-driven model go gain currency? Patagonia continues to launch programs like its Responsible Economy initiative and a backlash to Black Friday, “Worn Wear,” which suggests that we should enjoy what we already own.

Will the resilience push take hold? New York City released a $20 billion plan to get the city ready for more extreme weather — will companies embrace the risk-reduction benefits of different thinking and planning?

Finally, why haven’t more companies followed some of the recent sustainability leaders? Paul Polman at Unilever stopped providing quarterly guidance a few years ago so the company could focus on real value creation. And Microsfot and Disney remain really the only two big companies charging their own divisions a carbon fee (yes, as CDP recently reported, and the New York Times put on the front page, 29 large companies now use some kind of internal pricing for carbon. But most of these are “shadow prices,” in use for years, not actual fees. Why has the pace of change lagged the urgency of our mega challenges? Will more than a small number of companies embrace a much deeper change to business as usual?

So it’s been a mixed year, as I suppose all years are, but I remain optimistic that greater stories of change are coming. Have a very happy, healthy, and sustainable 2014!

Doing Less, Leading More

Our first accomplishments as professionals are usually rooted in our skill as individual contributors. In most fields we add value in the early stages of our careers by getting things done. We’re fast, we’re efficient, and we do high-quality work. In a word, we’re doers. But when we carry this mindset into our first leadership roles, we confuse doing with leading. We believe that by working longer, harder, and smarter than our team, we’ll inspire by example. Sometimes this has the desired effect–as Daniel Goleman wrote in his HBR article “Leadership that Gets Results,” this “pacesetting” leadership style “works well when all employees are self-motivated, highly competent, and need little direction or coordination.” But the pacesetting style can also carry a high cost – Goleman notes that it “destroys climate [and] many employees feel overwhelmed by the pacesetter’s demands.”

Instead simply doing more, sustaining our success as leaders requires us to redefine how we add value. Continuing to rely on our abilities as individual contributors greatly limits what we actually contribute and puts us at a disadvantage to peers who are better able to mobilize and motivate others. In other words we need to do less and lead more. Sometimes this transition is obvious and dramatic, such as when we’re promoted and obtain our first direct reports or hire our first employees. Suddenly we need to expand our behavioral repertoire to incorporate new leadership styles as a means of influencing others effectively. (“Leadership That Gets Results” provides a useful roadmap here, highlighting the styles that have the greatest positive impact or are used less frequently by managers.)

Subsequent transitions may be more subtle and nuanced, such as when we go from leading front-line staff to leading managers, who themselves must navigate this same transition. A coaching client realized that he was running his company as though he were the “Doer-in-Chief,” and this model of leadership had permeated throughout the organization and was holding everyone back. He revamped his role, delegating almost all of the tasks on his to-do list to his senior managers and had them do the same to their direct reports. Rather than simply creating more work for junior employees, this emphasis on leading rather than doing resulted in greater efficiencies throughout the company. In my client’s words, “We went from being firefighters to being fire marshals,” taking a more strategic approach to the business, redesigning inefficient systems, and solving problems before they became crises.

This emphasis on leading and not merely doing has had a profound impact on management education. In 2010 Dean Garth Saloner of the Stanford Graduate School of Business (where I’m an Instructor) told McKinsey that, “The harder skills of finance and supply chain management and accounting…have become what you think of as a hygiene factor: everybody ought to know this… But the softer skill sets, the real leadership, the ability to work with others and through others, to execute, that is still in very scarce supply.” We expect our students to have solid technical and analytical skills—to be effective doers. But we also expect that within a few years of graduation our students will be managing people who are even more technically and analytically capable than they are—and this requires them to be effective leaders.

Many of my executive coaching clients and MBA students at Stanford are going through a transition that involves a step up to the next level in some way. They’re on the cusp of a big promotion, or they’ve launched a startup, or their company just hit some major milestone. Very few, if any, of these people would say that they’ve “made it”; they’re still overcoming challenges in pursuit of ambitious goals. And yet their current success has created a meaningful inflection point in their careers; things are going to be different from now on. The nature of this difference varies greatly from one person to another, but I see a set of common themes that I think of as “the problems of success.” You can read my first and second posts on “the problems of success.”

Managing Designers on Two Different Tracks

Making creative expertise a lasting part of your company means more than just hiring a few designers. You also have to retain, direct, and eventually promote them — something that managers from other backgrounds can find daunting. Recommendations often fall into tired caricatures: creatives are temperamental, they demand constant stimulation, they should be indulged. Creative professionals do fare better when they’re given flexible schedules, meaningful work, and license to fail — but then, so do the rest of us.

Where they differ is in their long-term professional path. Or more correctly, their paths: in our experience at Ziba, we’ve seen two distinct career paths among creative professionals, each stemming from its own set of motivations, and demanding its own approach to management.

The Creative Director. More than money or recognition, what drives many top-notch creatives is the promise of perpetual newness. Modern design schools increasingly encourage this, demanding that graduates be familiar not just with a traditional creative skillset, but with ethnography, finance, coding, and a host of other competencies.

The good news is that the curiosity-driven creatives who come out of these programs can make excellent leaders, well-suited to the kinds of collaborative teams that spur innovation. Because they understand both the creative process and broader business considerations, they act as go-betweens, communicating requirements and constraints to creative team members, and championing creative work to clients and co-workers. Getting someone to this point, however, can take guidance that seems counter-intuitive.

For one thing, workers who seek the Creative Director path are often drawn to tasks that they’re not explicitly qualified for. As their manager, you should encourage this. Look for signs of interest outside their job descriptions, and give them expanded responsibility in those arenas. Acknowledge the possibility that they could be good at tasks that aren’t “creative,”and push them to oversee multiple facets of a project without losing their core competency.

J. Crew president Jenna Lyons exemplifies this path, having worked her way up from designing rugby shirts in 1990, until she elevated a formerly staid clothing brand into a high-margin force of fashion. A recent profile of Lyons, and her relationship with CEO Millard Drexler, depicts her poking fingers into every aspect of the business, from marketing strategy and manufacturing control to ensuring that photographers get the right jewelry for a shoot. Yet she is still emphatically a designer at the core, and respectful of the creative expertise around her. It’s a win-win situation for the company, bringing innovation and vision into its heart; it happened because she was given license to pursue her curiosity, and access to the broader organization.

The Master Craftsman. There are other creative professionals, though, who reject such breadth, wanting nothing more than to master the tools of their trade and solve the problems no one else can. At first glance, it might be tempting to dismiss someone with such narrow focus — shouldn’t all creative professionals eventually become directors? — but that would be a mistake. As fun as it is to try and spot the “trick” that brands like Virgin, Apple, or Target use to dominate their categories, the reality is that they all have cultures of perfect execution. They sweat out the details, making sure that every part of their offering is just right, and this takes obsessive craftsmen who won’t take “almost good enough” for an answer.

Managing these creatives means ensuring they have a clear way to advance without getting pushed into management. In practice, it often means defining a new position. At Ziba they’re called Principal Designers, but regardless of name, the position should confer status and authority on par with a Creative Director, so it becomes a target for continued improvement. Establishing this role also announces clearly, to the entire organization, that mastery is respected as its own form of leadership.

Creating a Master Craftsman path also challenges managers to formally encourage mentorship and evangelism. Principal Designers often relish working with less experienced counterparts to hone their skills, especially if it’s done with the blessing and support of the organization. Even when they’re not interacting with clients, they should advocate for the value of their craft, teaching non-designers how to leverage it for better outcomes.

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell argues (and defends in the New Yorker) that cognitively complex tasks take extensive practice to master — the well-known 10,000 Hour Rule. What sets Master Craftsmen apart is not innate talent, but fascination with that practice. Good managers value that fascination, and support it with professional tools, conferences, skill-sharing opportunities…and promotions. Craftsmen must know that as long as they keep improving, and helping others do the same, they’ll continue to advance.

When these two types of creative workers are combined, and supported equally through their career arc, companies are transformed. The tendency to seek out rockstar designers is gradually waning, but there’s a still a temptation to see lone genius as the source of innovation. Smart executives, on the other hand, know that creativity is nothing more — and nothing less — than consistent, highly skilled work. It should be managed that way.

The Fine Art of Tough Love

What does it take to achieve excellence? I’ve spent much of my career chronicling top executives as a business journalist. But I’ve spent much of the last year on a very different pursuit, coauthoring a book about education, focusing on a tough but ultimately revered public-school music teacher.

And here’s what I learned: When it comes to creating a culture of excellence, the CEO has an awful lot to learn from the schoolteacher.

The teacher at the heart of the book Strings Attached is on the face of it an unlikely corporate role model. My childhood music teacher Jerry Kupchynsky, who we called “Mr. K,” was strictly old school: A ferocious Ukrainian immigrant and World War II refugee, he was a tyrannical school orchestra conductor in suburban New Jersey. He would yell and stomp and scream when we screwed up, bellowing “Who eez DEAF in first violins?” His highest praise was “not bad.” He rehearsed us until our fingers were raw.

Yet ultimately he became beloved by students, many of whom went on to outsize professional success in fields from business to academics to law, and who decades later would gather to thank him.

My coauthor and I both expected pushback against Mr. K’s harsh methods, which we describe in unflinching detail. But instead, the overwhelming response from readers has been: “Amen! Bring on the tough love.” And nowhere has that response been stronger than in the business world, among corporate executives.

Indeed, Wall Street Journal readers responded in force to an essay I wrote about the book and Mr. K’s methods. “Time to move beyond the ‘self-esteem’ culture and get tough. The world is an increasingly competitive and dangerous place,” as one reader wrote, echoing many others. He added, “I have numerous advanced degrees, but the toughest and best education I ever had was from the Irish Christian brothers in high school. They did not take ‘no’ for an answer.”

Clearly, Mr. K’s demanding methods have tapped into a sea change that we’re just starting to detect in the culture, away from coddling of kids and the “trophies for everyone” mentality that has dominated parenting and education. It’s a shift that is equally evident in the workplace. But trying to offer more honest feedback, and set higher standards, at work is tricky. It’s especially difficult in the case of newer hires, those recent young college grads who were raised on a steady diet of praise and trophies and who never learned to accept criticism.

So, how best to put those “tough love” principles into action when it comes to inspiring excellence in the workplace? Mr. K’s methods offer an intriguing roadmap:

1. Banish empty praise.

Mr. K never gave us false praise, and never even used words like “talent.” When he uttered a “not bad” – his highest compliment — we’d dance down the street and then run home and practice twice as long.

It turns out he was on to something. Harvard Business Review readers will recall the landmark 2007 article written by psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, “The Making of an Expert.” That piece is most often cited for his pioneering work establishing that true expertise requires about 10,000 hours of practice.

But Ericsson also cited two other elements, both of which Mr. K seemed to know intuitively. One is “deliberate practice,” which requires pushing yourself beyond your comfort zone, as opposed to going through the motions. The other, as Ericsson wrote, is this : True expertise “requires coaches who are capable of giving constructive, even painful, feedback.” And “real experts … deliberately picked unsentimental coaches who could challenge them and drive them to higher levels of performance.”

2. Set expectations high.

There’s a tendency to step in when a less experienced colleague is having trouble. Sometimes it seems it’s just easier to do the work yourself. Or to settle for less.

Not in Mr. K’s world. His standards were uncompromising – and while at first we students found that intimidating, we ultimately understood it was a sign of his confidence in us. He never wavered in his faith in his students to achieve more and better. When he first began teaching me the viola, his most frequent admonition was “AGAIN!” most often marked in capital letters on my lesson assignments. But his students knew that he was hard on us not because we’d never learn, but because he was so absolutely certain that we would.

3. Articulate clear goals –and goal posts along the way.

Mr. K insisted that his students audition and perform constantly. He constantly kept us focused on the next challenge. How would we prepare, and what would we do to improve the next time? By articulating these intermediate goals, he encouraged us to continually stretch our abilities a bit further while reaching for objectives that were challenging, but ultimately achievable.

4. Failure isn’t defeat.

Mr. K never penalized us for failure. Sometimes we succeeded at auditions; sometimes we failed. But Mr. K made it clear that that failure was simply part of the process – not an end point, but simply an opportunity for us to learn how to improve the next time. And he transferred responsibility for figuring out the solution to the student. His favorite saying wasn’t “Listen to me!” It was, instead, “Discipline yourself!”

Years later, his former students – now doctors, lawyers and business executives – would credit that approach for instilling self-motivation. As one of his former students told me, “He taught us how to fail – and how to pick ourselves back up again.”

5. Say thank you.

This is the one we often forget. My old teacher had witnessed unspeakable horrors as a child growing up in Ukraine amid bloodshed and destruction during World War II. He didn’t reach the U.S. until after the war, as a 19-year-old who spoke no English and had never had the opportunity to learn to read music despite his passion for it. He never lost his sense of gratitude to this country for the opportunities he had, despite a catalog of horrors in his own life, including the disappearance of one of his beloved daughters. He passed that gratitude on to us, with a huge heart, empathy for the underdog, and a commitment to public service, taking us frequently to perform at hospitals and nursing homes and then insisting we stay to visit with the patients.

In the press of business, that sense of gratitude is often the first casualty. Recently I complimented a young journalist on a well-researched article, telling her, “You must have gotten great feedback.” She looked embarrassed, then confessed she had heard nothing from her boss. Her news organization, like so many others, has been financially hobbled, with a handful of reporters doing the work that was once shared by several dozen. Her supervisor is spread so thin that he is putting out proverbial fires all day. “He has the time to tell us what we did wrong,” she said. “He doesn’t have time to tell us when we do something well.”

* * * * *

Tough love has fallen out of favor, and it can be a jolt especially for younger workers. But properly applied – with high expectations along with a sense of shared vision and gratitude for a job well done — it is the highest vote of confidence anyone can offer. Mr. K’s old students ultimately figured that out too: At his memorial concert, 40 years’ worth of them – myself included, toting my old viola – gathered in my hometown, old instruments in tow, creating a symphony orchestra more than 100 members strong.

I asked many of those students why they had returned. They listed the qualities he had taught them: Resilience. Perseverance. Self-confidence. He didn’t just teach us in the classroom; he inspired us to strive for excellence in our own lives when he was no longer in the room with us. And that’s the mark of a true mentor: a leader who creates a culture of excellence, and whose confidence in us makes us better than we ever dreamed we could be.

December 16, 2013

How an Auction Can Identify Your Best Talent

My children go to public school in New York City. As in many school systems across America, parents help raise vital funding each year to complement the often scarce resources provided by the public school system. In my community, the biggest fund-raising event of the year is the annual school auction featuring live and silent bidding. The silent auction part is simple: Items donated by local businesses and generous individuals are displayed on a table next to a bidding sheet. Bidders compete by writing their names, paddle number, and price on the sheet. At the end of the night, the prize goes to the highest bidder.

Teachers like to contribute to this fund-raising event, too. But instead of donating an item, teachers donate their time, offering a shared experience with a student at places like the Museum of Natural History, Lincoln Center movie theater, or the Bronx Zoo.

I have attended the annual auction for years. While it’s always an enjoyable event, one particular aspect of the evening has always fascinated me — that teachers have essentially created an open marketplace with parents competing for their time in what is traditionally a closed system. When the auction ends and the silent bidding sheets are filled, a pattern emerges that identifies the “good” teachers: Teachers in high demand have numerous entries on their bid sheets, as parents are willing to pay the premium price for a coveted afternoon with the best teachers. Conversely, the teachers in low demand go for lower prices – with some not even receiving a single bid (ouch). Year after year, the same teachers are in high demand, selling for big bucks. As a consumer of the teacher’s services — at least, my children are — I use this market data to decide which teacher’s class I want my child in the next year. (In reality of course, I don’t get to select my children’s teachers. The school administration does. Nevertheless, I remain aware of which teachers continually get high marks in case I am ever given the choice.)

In reflecting on the teacher silent auction, I began to wonder why we don’t deliberately create markets within our corporations to set the conditions or incent the best service from corporate functions. We all know that options and competition in markets breed higher quality, lower cost, and greater innovation. Our entire economic system (as imperfect as it is) is based on this concept. However, there is one place where options and market forces tend to be absent — in the function departments of large corporations.

Let me explain. Typically, corporate departments operate as monopolies with no other options available to employees that use their services. Monopolies exist when a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular commodity or service, and are characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce the good or service and a lack of viable substitute goods. They are less efficient and innovative over time, becoming “complacent giants” because they have to be neither efficient nor innovative to compete in the marketplace. While it’s not their only role, corporate departments do provide services (finance, legal, information services, market research, and so on) to employees. They are the only service provider. If the employee doesn’t like the service from HR or the IT help desk, he can’t go to another service provider. Employees are required to use the mandated corporate departments.

However, what if corporations set up their work environments so employees had choices about how they wanted to work and from where they received their support? What if the corporate department had to compete for the business of the employee — every month, every week, every day or even on every project? What would happen? For instance, if an employee had the option of management training from the corporate HR (training) department or from the sales department in the business unit, each training provider would have to continually innovate the content, delivery and cost of their service in order to win customers (in this case, employees). Otherwise they’d risk going out of business (being eliminated). Each department would also have to be externally focused to ensure their offering was comparable or superior to management training available in the market or else risk the same fate.

I have seen only two companies institute a program that follows this model. In these companies, the employees have options about which provider they want to use for the services they consume, thus turning the system upside down and creating departmental competition within the corporation. In one of these organizations, two different teams offered similar services (market research, business analytics and secretarial support) – one team was in the corporate center and the other was part of a division that had brought the services in-house. Over time, employees began choosing the division provider, with its higher quality output, over the corporate center. The result? While employees received better, faster and less expensive service, the corporate center faced hard times. Several employees were redeployed and retrained to focus on niche areas, while others were let go and their positions taken as a cost savings by the company. Additionally, where the corporate department had been successfully using vendors to provide the same service, the vendors were told they must meet the new internal service-levels, cost, turnaround time, and quality — otherwise they would lose the contract. Ultimately one vendor did lose the contract and quickly went out of business while another accepted the new conditions and figured out a way to deliver under the more challenging requirements.

Creating competition in the work place can be a controversial practice. But if you think about it, we already have competition. We are so used to it being a regular part of corporate life that we typically don’t perceive it as competition. In fact, though, we compete for resources during the budgeting process, for a fixed bonus or merit increase pool, for promotions or new positions.

Market forces might not work inside every organization — but they just might work in yours. Wouldn’t you want to know whether your corporate functions are the star teachers or the duds?

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

The American Way of Hiring Is Making Long-Term Unemployment Worse

We Can Now Automate Hiring. Is that Good?

Learn How to Spot Portable Talent

Why Japan’s Talent Wars Now Hinge on Women

Even Small Companies Can Tap Big Data If They Know Where to Look

Small and medium-size businesses are often intimidated by the cost and complexity of handling large amounts of digital information. A recent study of 541 such firms in the UK showed that none were beginning to take advantage of big data.

None.

That means these firms and a lot of others are at a serious disadvantage relative to competitors with the resources and expertise to mine data on customer behaviors and market trends. What these data-poor companies don’t know is that it’s possible to get a lot of value from big data without breaking the budget. I discovered this while researching my book Too Big to Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data. In fact, the above UK study notwithstanding, I found that plenty of small and midsized companies are doing interesting things with data, and they aren’t spending millions on it.

True that in the past, companies seeking to tap into big data needed to purchase expensive hardware and software, hire consultants, and invest huge amounts of time in analytics. But trends such as cloud computing, open-source software, and software as a service have changed all that. New, inexpensive ways to learn from data are emerging all the time.

Take Kaggle, for instance. Founded in 2010 by Anthony Goldbloom and Jeremy Howard, the company seeks to make data science a sport, and an affordable one at that. Kaggle is equal parts funding platform (like Kickstarter and Indiegogo), crowdsourcing company, social network, wiki, and job board (like Monster or Dice). Best of all, it’s incredibly useful for small and midsized businesses lacking tech- and data-savvy employees.

Anyone can post a data project by selecting an industry, type (public or private), participatory level (team or individual), reward amount, and timetable. Kaggle lets you easily put data scientists to work for you, and renting is much less expensive than buying them.

Online automobile dealer Carvana, a start-up with about 50 employees, used Kaggle to offer prizes ranging from $1,000 to $5,000 to data modelers who could come up with ways for Carvana to figure out the likelihood that particular cars found at auctions would turn out to be lemons. For the cost of the prize money (a total of $10,000), Carvana got “a hundred smart people modeling our data,” says cofounder Ryan Keeton, and a model that the company was able to host easily and inexpensively.

Even a lack of data isn’t an insurmountable obstacle to harnessing analytics. Data brokers such as Acxiom and DataLogix can provide companies with extremely valuable data at reasonable prices. As Lois Beckett writes, “There’s a thriving public market for data on individual Americans—especially data about the things we buy and might want to buy.” For example, a marketing-services unit of credit reporting giant Experian sells frequently updated lists of names of expectant parents and families with newborns.

A number of start-ups are jumping into this space—open-database firm Factual recently closed $25 million in series A financing, led by Andreessen Horowitz and Index Ventures. The company is building datasets around health care, education, entertainment, and government.

Do Kaggle, Factual, and their ilk represent the classic business disruption that will turn the data industry upside-down and make consumer and market information available to every company, large and small? No—they don’t portend the imminent demise of corporations’ in-house data analysis or of high-priced analytics firms. But they’re providing attractive alternatives for companies that can’t afford to—or simply don’t want to—hire their own data scientists.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

Executives Ignore Valuable Employee Actions that They Can’t Measure

Big Data’s Biggest Challenge? Convincing People NOT to Trust Their Judgment

Small Businesses Need Big Data, Too

How to Get More Value Out of Your Data Analysts

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers