Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1492

December 23, 2013

Parents May Be Your Secret Weapon For Recruiting and Retaining Millennials

A recruiter at a well-known Fortune 10 company told me this story: She was getting ready for a phone interview with a new college graduate. But when she dialed into the conference number at the scheduled time, instead of the candidate, there was an older woman on the line.

The female caller identified herself as the applicant’s mother and said, “I know you were expecting a call with John (not his real name), but he’s tied up in another interview at the moment. Fortunately, I know him so well that I can do the interview for him. Do you mind?”

The recruiter understandably replied that she did mind and asked John’s mom to have her son call when he was available.

If you suspect this conversation is an anomaly (and a shocking one at that!), think again. I speak with large groups of HR executives several times a month and when I ask the question, “How many of you have had a parent get involved in the hiring process?” at least half raise their hands, sometimes, two thirds.

I often follow up by asking how many have had a parent intervene in the performance review process. About a third raise their hands to this question. Rather than being surprised by all the hands in the air, the executives seem comforted knowing that others are in the same boat when it comes to recruiting and retaining Millennials.

This is a new reality: Parents are increasingly involved in their Millennials’ decisions. According to one study, more than a third of Millenials with a mentor say a parent fills that role. In another study, when asked to list the most influential people in their lives, 61% named their parents ahead of political leaders, news media, teachers, coaches, faith leaders, and celebrities. Pew Research reports that 36% of Millennials still live with their parents.

In a sense, knowing that a single group yields so much influence with Millennials makes your job designing strategies for attracting and retaining them easier. Parents may very well be your secret weapon in convincing Millennials to join or stay at your organization.

Here are five ideas for integrating parents into your talent strategy:

Invite parents in. College recruitment has long included parental visits and open houses the first week of school. Some Indian companies, recognizing the importance of family, are doing the same: welcoming parents to new employee orientation (a few have even taken it a step further and offer benefits to dependent parents, strengthening the employee bond). Why not invite parents to your employee orientation or onboarding program? You might let them visit during an open house or join a conference call to ask questions about benefits, understand the employee value proposition, and link them emotionally to your brand.

Offer free training for parents. Since mentoring is the number one way Millennials choose to learn, and the parent is frequently chosen as a mentor, consider preparing mom and dad for the role. Give them mentoring skills as well as training on problem solving, interpersonal skills, communication, leadership, or even the performance review process. The idea is that if you give parents these skills, they will hopefully transfer what they learn to their child — your employee.

Hold a “Take Your Parents to Work” day. LinkedIn held their first Bring in Your Parents Day this past November. It was “designed to help bridge the gap between parents and their professional children.” According to their research: 35% of the parents they surveyed are not completely familiar with what their child does for a living; 59% of parents want to know more about what their child does for work; and 50% of parents say they could be of benefit to their offspring by having a better understanding of their careers.

Use parents to recruit. Again, universities are already doing this, so it’s not new but consider interviewing parents and including their stories on your Facebook recruiting site (you do have one, don’t you?). Or put them on your open house agenda and ask them to share their stories as an employee parent.

Include parents in your communication strategy. Allow parents to subscribe to your newsletter or other communications that engage them in the company culture. All new Qualcomm employees are automatically registered to receive an online story each week for their first year. The stories start with the founding of the company and go all the way to present day, describing the history of the company’s technology successes and failures, as well as the rationale behind key decisions, all while memorably conveying the company’s culture. Parents might enjoy reading this as much as — or even more than — their children, and again they might use it while mentoring or advising their children.

None of these strategies are expensive and yet they can go a long way in attracting and retaining Millennials. Simply acknowledging the importance of moms and dads in their lives will help you stand out from other companies. Instead of shaking your head at this trend of increasing parent involvement in your employees’ work lives, embrace it.

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

Never Say Goodbye to a Great Employee

How an Auction Can Identify Your Best Talent

The American Way of Hiring Is Making Long-Term Unemployment Worse

We Can Now Automate Hiring. Is that Good?

What Would an Economist Give to Be Published?

Having heard an economist lament that he would give his “right arm” to be published in the prestigious American Economic Review, a team led by Arthur E. Attema of Erasmus University Rotterdam in The Netherlands set out to discover whether his colleagues would indeed sacrifice a limb for publication. The team asked, essentially, by how many years the economists would be willing to shorten their lifetimes in exchange for publication in the journal, then compared that with the participants’ answers to how many additional years they would accept in exchange for losing the thumb of their writing hand. Results from the 85 respondents imply that they would sacrifice more than half a thumb for an AER publication. At least one economist refused to answer on the grounds that the questions were ridiculous.

To Compete with E-Commerce, Retailers Need to Leverage Mobile

More and more shoppers are finding that online shopping offers greater convenience, lower prices, more information, and a more personalized user experience that makes buying online preferable to going to a store. And as free shipping becomes more common, one of the last remaining barriers to e-commerce is falling. The shift was reflected in this year’s Black Friday weekend numbers. Although sales were essentially flat overall, online sales grew as a share of total sales by 28 percent from the previous year.

In the physical world, retailers have become quite adept at following the relatively faint tracks shoppers leave in their stores, primarily through their participation in loyalty schemes. However, in most cases this data is leveraged only after shoppers have paid at the register. Retailers can’t tell what shoppers looked at but didn’t buy, or whether they forgot something that they likely needed. Digital engagement gives e-commerce sites a huge advantage. Shoppers leave digital footprints across websites, mobile apps, and social media. Innovative sites also leverage analytics to optimize the experience.

But mobile shopping also represents a rapidly growing share of e-commerce, accounting for more than 20 percent of e-commerce sales this holiday season. And mobile provides a unique opportunity to help physical retailers compete.

Shoppers already use their phones to access online product information such as reviews or to cash in digital coupons. And now, some retailers are using mobile to connect with shoppers even before they walk into the store. For example, some offer apps that help consumers find where they can buy a product, check that it is in stock, and locate it in the store itself. Walmart’s mobile app not only provides pre-store support via shopping lists, mobile ordering with site-to-store shipping and other features, but also allows consumers to switch into ‘shopping mode’ once they are in-store to access an array of tools including store maps. ‘Shopping mode’ also aids Walmart employees by enabling them to adjust the offers that shoppers are served at a store level.

While some shoppers do use their phones inside the store to order from a rival — think of a shopper who finds a book at a local bookstore but orders a discounted version on their Amazon app — some retailers are taking advantage of mobile to offer shoppers the ability to order from a broader assortment of their own products. Home Depot’s mobile app provides consumers with access to an ‘endless aisle’ of more than 400,000 products – a small selection of which is carried in its physical stores at any time.

Retailers can also upgrade their traditional loyalty programs using mobile technology. For example, Walgreens’ one-stop-shop app creates an integrated experience for health and wellness across consumer needs. Consumers can use the Walgreens app for prescription refills via barcode scanning, medication reminders, photographic orders and loyalty card point tracking. Solutions are personalized via activity and triggers captured through the app, driving high consumer stickiness. Mobile refills now represent 50-plus percent of all online orders, an increase from 10 percent in 2010. Highly engaged Walgreens customers spend six times more online, in-store, and mobile combined.

For physical retailers, tapping into the mobile opportunity requires focusing on new capabilities for analytics, content development, and social media management. But the key to capturing share and surfing the digital wave — rather than getting walloped by it — is keeping the focus on people, not technology. Designing and building human-centered digital experiences can help physical stores survive — and thrive. Mobile provides an opportunity to connect the product and services provided more closely to the pre-store experience and to enrich the experience during the store.

December 20, 2013

How to Lead During a Data Breach

In 2007, I wrote a case study for Harvard Business Review, “Boss, I Think Someone Stole our Customer Data.” Now six years later, an actual event has occurred that is eerily similar to that fictional scenario: a trusted retailer’s point-of-sale system security was breached and a large amount of customer data may be compromised.

In the current situation, the retailer is much larger as is the number of accounts affected. The New York Times reported that as many as 40 million customers may be affected by the data breach at Target. This makes it the third largest in history. The breach is reported to have started just before Thanksgiving and continued until December 15 – right in the heart of the most important selling season of the year. Full disclosure: Target executives have attended the executive education program where I am Director of Research. I worked with Visa on its Data Security Summit in 2007. I also hold a card that may have been compromised.

The investigation by law enforcement officials will determine who is to blame. Executives in any business, however, can learn valuable lessons in crisis leadership:

One critical concept that we share with the participants in the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative (NPLI) at Harvard is that every crisis includes many situations, each with different contingencies and considerations. In this case, they include security, legal, law enforcement, customer relations, media, shareholder, employee, the board, card issuers and providers, regulatory, and more. While there can be overlap, each of these situations has a distinct (and sometimes conflicting) set of stakeholders, power structures, priorities, perspectives, interests, requirements, and values. For example, Communications may want to be immediately open and transparent while Legal may want to wait to more fully assess the liability exposure that such a stance could create. They each have a legitimate case. Navigating this complex web of interdependent relationships is daunting in routine times. In a crisis of this magnitude, the added pressure and higher stakes can make it overwhelming. How can an executive successfully lead through such a complex morass?

The first step is to ensure certainty about the values that will drive decision making. In this case, trust should be the “true north” for Target in its dealings with its many stakeholders. The breach itself and the fact that the source of the disclosure was a blogger, not the company, were both hits to Target’s perceived trustworthiness. Company executives should recall the key lesson from the famous Johnson & Johnson response to the Tylenol scare in 1982: CEO James Burke saw that the most important objective was to restore the confidence of customers and other critical stakeholders, and moved aggressively to do that. If there is a short-term financial hit, take it and move forward. Clearly shared values among leaders in the business can help prevent or resolve conflicts as operational options and objectives are weighed.

The second step is to map the constellation of situations and their stakeholders. This can be done on a white board or sheet of paper. It doesn’t require a lot of detail; the purpose is to fix in your mind the awareness that you are dealing with a complex, dynamic problem. The angle you overlook in the crisis may be the one that causes the greatest damage in the end. Always remember that the original event – here, the data breach – is one crisis but the response may ignite a series of secondary crises if not handled well. (Remember Katrina.) This is particularly true in crises where the media takes an interest. Media stories will help shape the perceptions of many stakeholders and this, in turn, will set attitudes and interactions going forward. Many of these factors are beyond your control, but they are rarely outside of your sphere of influence.

With that situation map drawn, look for gaps in your crisis response: something not planned for or a need not met in the heat of action. After all, no action plan gets everything just right. It is critical to perceive the weak spots or holes in your efforts and take mitigating steps. Figure out who has something to give to close a gap – from tangible assets to moral and reputational support –and who needs to get something to do the same. Playing problem-solution matchmaker between “gives” and “gets” helps you to leverage and optimize resources in dealing with the many crisis situations.

The crisis will evolve over time and so must your perception of it. Target likely took action and had a disclosure plan prior to yesterday’s revelations in the media. However, an influential security blogger’s post followed by national and international media attention changed everything. The challenge for company leaders was then to re-orient the response to an increased pace with altered dynamics; control of messaging shifted from the company to news outlets. Embracing the patterns of this new reality, a leader must anticipate what is likely to happen next. Only then can he or she take the right steps. This is a continuous loop of adaptive thinking — perceiving, orienting, and predicting – and acting – deciding, operationalizing, and communicating.

The final lesson from this incident is “never say never.” Target is a company that takes security and customer trust seriously. The payment card industry has a rigorous set of standards, procedures, and protocols, and penalties for non-compliance, that are in use with virtually all major merchants in the United States. Yet breaches still occur. The United States is a particularly rich target because our credit and debit cards rely on magnetic strips rather than chips for validation; it is an old technology – though when paired with new fraud monitoring technologies it has kept actual fraud at bay. But these cards are easier for criminals to duplicate than chip cards, which makes them a more tempting target.

Your business or industry likely has corresponding vulnerabilities. In an increasingly complex and turbulent world, any day could be the one that your career or even your company depends upon your skill leading through a crisis. Are you ready?

The Organization of Your Dreams

We have known for about 150 years that people who enjoy their work are more productive. That is to say high satisfaction is correlated with high performance. And yet many organizations seem to go out of their way to make work alienating, frustrating, and unpleasant. This is evidenced in the depressingly low rates of employee engagement around the world. According to a recent AON Hewitt survey, four in 10 workers on average report being disengaged worldwide (three out of 10 in Latin America, four in ten in the U.S., and five in 10 Europe).

This finding resonates with our latest research. For more than four years now, we have been asking people what an “authentic” organization would be like – that is, one in which they could be their best selves. While individual answers vary, of course, we consistently find that they fall into six broad imperatives, which describe what we call “The organization of your DREAMS,” a handy mnemonic, whose components are:

Difference – “I want to work in a place where I can be myself.”

Radical honesty – “I want to know what’s really going on.”

Extra value – “I want to work in an organization that makes me more valuable.”

Authenticity – “I want to work in an organization that truly stands for something.”

Meaning – “I want my day-to-day work to be meaningful.”

Simple rules – “I do not want to be hindered by stupid rules.”

This may seem obvious. Who would want to work in the opposite kind of place — an organization where conformity is enforced, where employees are the last to know the truth, where people feel exploited rather than enriched, where values change with the seasons, where work is alienating and stressful, and where a miasma of bureaucratic rules limits human creativity and effectiveness? That’s the organization of your nightmares, not your dreams!

And yet we find that few organizations fulfill all the elements of this dream workplace.

Why? Our research indicates that many tackle these issues (and it’s not like they’re not trying to) far too superficially. They apply sticking plaster or Band-Aids to problems when they arise and seem unprepared to tackle fundamental underlying issues. What issues are these?

Let’s begin with Difference. For many organizations, accommodating differences translates into a concern with diversity, usually defined according to the traditional categories of gender, race, age, religion, and so on. These are, of course, of tremendous importance, but the executives in our research were after something subtler and harder to achieve – an organization that can accommodate differences in perspective, habits of mind, core assumptions, and worldviews. Indeed, these executives have actually become resistant to the conventional diversity agenda. We were recently in an organization that had produced a 142-page booklet called “Managing Diversity.” (We wonder how many people will actually read it.) And yet in all those pages, the crucial argument that creativity (a key index of performance) increases with diversity and declines with conformity is never really made.

What about Radical Honesty? Organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of communications – both internally and to wider stakeholders. One key indication of this is that we are now finding communications professionals at or near the summit of organizations. This is a step in the right direction, for we have all learned that reputational capital is becoming more and more important for high performance — and at the same time increasingly fragile. Think of Arthur Andersen, arguably the greatest professional services organization in the world, which ceased to exist within a month after the Enron scandal. Still, the growth of the communications profession is actually more evidence that companies are taking a superficial approach to the dissemination of critical information – the kind high performers need to do their jobs. The mind-set of so many communications professionals remains stubbornly connected to an old world in which information is power and spin is their key skill. Surely information is power, but companies need to acknowledge that they no longer have control of it. In a world of WikiLeaks, whistle blowing, and freedom of information their imperative should be to tell the truth before someone else does.

How can organizations create Extra Value? Elite organizations and professions — the McKinseys, Johns Hopkins Hospitals, and PwCs of this world – have been in the business of making great people even better for a long time now. Part of their pact with employees is “Join us and we will develop you.” But they deal with only a tiny proportion of the workforce. What about the rest of us? Our research shows that high performance arises when individuals all over the organization feel they can grow through their work — adding value as the organization adds value to them. And that means the administrative assistants and cashiers, as well as the executives and the shift managers. This is not impossible – if a company like McDonald’s U.K. finds it profitable to train the equivalent of six full classes of students every week to attain formal qualifications in math and English, surely other companies can do more.

What does it mean for an organization to be Authentic? This is a big question. We have developed three markers of authenticity. First, a company’s identity is consistently rooted in its history. Second, employees demonstrate the values the company espouses. And third, company leaders are themselves authentic. This is clearly not simple to achieve. Sadly, rather than rise to the challenge, in many organizations the task of building authenticity has collapsed into the industry of mission-statement writing. People we’ve interviewed despair as they tell us of mission statements rewritten for the fourth time in three years! Not surprisingly, this produces not high performance but deep-rooted cynicism.

The search for Meaning in work is not new. There are libraries full of research on how jobs may produce a sense of meaning – and how they can be redesigned in ways that produce “engagement.” But meaning in work is derived from a wider set of issues than those narrowly related to individual occupations. It also emerges from what we have called the three C’s – connections, community, and cause. Employees need to know how their work connects to others’ work (and here, too often, silos get in the way). They need a workplace that promotes a sense of belonging (which is increasingly difficult in a mobile world). And they need to know how their work contributes to a longer term goal (problematic, when shareholders demand quarterly reporting). If these issues are not addressed, engagement efforts will have only fleeting effects.

Finally, the organization of your dreams has Simple — and agreed upon — Rules. Many organizations display a form of rule accretion, where one set of bureaucratic instructions begets another, which seeks to address the problems created by the first set. In response to this, organizations have attempted a kind of radical delayering. This has at least addressed the problem of losing ideas and initiatives in a byzantine hierarchical structure. But that, too, is only a superficial fix. The company of our dreams is not a company without rules – it is a company with clear rules that make sense to the people who follow them, a much larger challenge, with a far greater payoff.

We used to think that high-performance organizations had “strong” cultures within which individuals did or did not fit. But the paradigm has flipped. In the new world, organizations must increasingly adapt to the individuals they wish to engage. This is at the core of the organization of your dreams. Sustained high performance requires nothing less than a reinvention of the habitual patterns and processes of organizations.

Culture That Drives Performance

An HBR Insight Center

There’s No Such Thing as a Culture Turnaround

The Three Pillars of a Teaming Culture

Three Steps to a High-Performance Culture

If You’re Going to Change Your Culture, Do It Quickly

Guess Who Got Rejected from Top B-Schools?

It's not especially surprising that there's steep competition to get into these two top business schools. But rejections of accomplished candidates without even an interview can be perplexing — especially for the rejectees. John A. Byrne of Poets and Quants, a web site focused on business education, asked Sandy Kreisberg, an MBA admissions consultant, to analyze why three particular people were left hanging. The first is an Indian-American who graduated from Wharton with a 3.45 GPA, worked at L.E.K. and Barclays, scored a 740 on the GMAT, and climbed Mount Everest. The verdict? He's a solid silver with a lowish GPA and experience at second-tier consultancies. "No surprise here," says Kreisberg. The second is a woman with two start-ups under her belt and a 3.5 undergrad GPA. "I believe you were rejected because of your lowish grades," speculates Kreisberg. Also, "schools are suspicious of start-ups because any moron can do one and many have."

The last candidate, a 26-year-old man with a 3.15 GPA and biomedical experience at Abbott Labs, is more of a puzzle for Kreisberg. While the candidate suspects his low GPA is the problem, the consultant points out that his 790 GMAT is strong and that Abbott Labs is "something, well, I have heard of." She suspects it's the small stuff that got him rejected — maybe the total package makes him seem like "a brainiac with limited social skills."

Epic Fails at the Worst TimeFrom Weight Loss to Fundraising, “Ironic Effects” Can Sabotage Our Best-Laid PlansThe Guardian

You’re in a meeting, making a mental note not to mention some politically sensitive topic, when you suddenly find yourself blurting it out. The “ironic effect,” as psychologists call it, is a very specific kind of mistake in which you fail not despite your best efforts but precisely because of them. Trying hard not to mess up doesn’t make you more vigilant. It increases your anxiety, which decreases your self-control. One particularly insidious form of the effect, called “motivated forgetting,” can make awareness campaigns backfire, according to new research forthcoming from the Journal of Consumer Research. In the study, students who had been made aware of their university’s poor performance were less likely to remember an ad for a discount at the campus bookstore. The anxiety induced by the negative message about the school’s reputation prompted the students to find a way to forget everything having to do with the school in order to retain their sense of self-control. This dynamic can undermine any campaign that focuses on the dangers of failing to take some course of action — such as, say, getting a flu shot or a cancer test. —Andrea Ovans

Everyone’s an EditorThe Ability To Edit Tweets Would Have Huge Implications For How Brands Use TwitterBusiness Insider

Dash off 140 characters on the spur of the moment and they live forever in cyberspace, perhaps endlessly retweeted. But what if you made a mistake, or circumstances change, or you said something you regret? Help may be on the way. Twitter is reportedly working on a feature that will let you edit a tweet after it’s published and instantly apply the edits to all the retweets. Maybe to limit the amount of revisionist history, Twitter will limit the time period in which you can change your tweet, and you’ll be allowed to edit it only once (so you’d better be more careful about those second thoughts than you were about the first ones). This is expected to be a boon to marketers (and drunken actors) wanting to correct a tweet that’s causing a PR disaster and to journalists needing to amend misleading breaking-news reports. But mindful of possible abuse, Twitter is also working on an algorithm to prevent enterprising businesses from recasting tweets of theirs that have gone viral into advertisements. —Andrea Ovans

Controlling the Beast An Emotional Approach to Strategy Execution Insead

Emotions tend to be taboo in the business world, but researchers at Insead are talking about them and learning how they affect strategy and operations. One of the more interesting strands of research is on "collective emotions" -- the combined feelings of a group, such as a unit or an entire workforce. If not well managed, a cluster of people who have nasty things to say about their company's direction can expand to become "a vast coalition of individuals sharing negative emotions about the strategy." Tides of emotions like this can prompt middle managers to sabotage the implementation of a strategy even if their personal interests aren't directly threatened. One way to stem the flow of negativity is to encourage people to talk about how they’re feeling, and why, in a climate of psychological safety, writes Quy Huy, an associate professor. Dealing with collective emotions requires an investment in “emotional capital” — an ability to read others' emotions and regulate one's own. —Andy O'Connell

No Sympathy for the Devil You Never Give Me Your MoneyNewsweek

Meet Allen Klein, an accountant who, according to an excerpt from a new book by John McMillian, is responsible for the following: negotiating a blockbuster contract for the Rolling Stones; using this contract to try to pressure the Beatles into signing with him; tricking the Stones into giving him rights to all of their songs recorded before 1971; and loudly proclaiming for all to hear that he would one day manage the Beatles. He eventually did (sort of) -- but only after exploiting a growing rift between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Klein proved ruthless in how he got Lennon on his side, reflecting on their similarly lower class upbringing, lavishing praise and false promises on Yoko Ono, and eventually winning over George and Ringo. "When John, George, and Ringo outvoted him three to one in favor of Klein, [McCartney stated that] it was 'the first time in the history of the Beatles that a possible irreconcilable difference had appeared between us.'"

So can you say that management, persuasion, and tough-as-nails negotiation broke up the Beatles? Not exactly — that would be a little too simplistic. But what a (sometimes disturbing) window into the business of rock 'n’ roll.

BONUS BITSFirst Impressions

The Science of Meeting People (Wired)

Should Your Credit Score Matter on Job Interviews? (Forbes)

Take the Bagel and Run (The Toast)

Algorithms Won’t Replace Managers, But Will Change Everything About What They Do

The labor market is about to be transformed by machine intelligence, the combination of ubiquitous data and the algorithms that make sense of them. That’s according to economist Tyler Cowen, in an argument spelled out in his recent book Average is Over. As Cowen sees it, your job prospects are directly tied to your ability to successfully augment machine intelligence. He writes:

Workers more and more will come to be classified into two categories. The key questions will be: Are you good at working with intelligent machines or not? Are your skills a complement to the skills of the computer, or is the computer doing better without you? … If you and your skills are a complement to the computer, your wage and labor market prospects are likely to be cheery. If your skills do not complement the computer, you may want to address that mismatch. Ever more people are starting to fall on one side of the divide or the other. That’s why average is over.

But what about management? I interviewed Cowen last month about his vision of the future, and where he sees managers fitting into it. An edited version of our conversation follows.

WF: What do you see as the main career lessons of the book?

TC: One thing the book suggests is that only being technically skilled may not be that useful, because those jobs can be outsourced or even turned over to smart machines. But people who can bridge that gap between technical skills and knowing some sector in a way that’s more creative or more intuitive, that’s where the large payoffs will come.

A classic example is Mark Zuckerberg with Facebook. Obviously a great programmer, but had he just gone out to be paid as a programmer he wouldn’t be that well off. He was a psychology major — he understood how to appeal to users, to get them to come back to the site. So he had that integrative knowledge.

For people who are not technically skilled, marketing, persuasion, cooperation, management, and setting expectations are all things that computers are very far from being good at. It comes down to just communicating with other human beings.

WF: Where does management fit into this?

TC: In any company, you need someone to manage the others, and management is a very hard skill. Relative returns to managers have been rising steadily; good managers are hard to find. And, again, computers are not close to being able to do that. So I think the age of the marketer, the age of the manager are actually our immediate future.

WF: I was talking recently with Andrew McAfee of MIT, whom you reference the book, and he mentioned the way software might even replace some pieces of management, though not managers themselves. Do you see algorithms and software encroaching majorly into that area?

TC: If it’s just measuring how hard people work, how long they’re at their desks, how good a job they do, how good a doctor or a salesman is adjusting for quality of customer, there’s a huge role there for software. But to actually replace managers, for the most part I don’t see that. At least not for the time horizon I’m writing about, 10 to 20 years out.

WF: One thing that McAfee talks about is the idea that people want to get their information from a human; they can be very distrustful of a computer just spitting out a recommendation.

Do you see that being true in a management context as well? That part of my job, if I’m running a company or division, is being able to understand machine intelligence and deliver it personally?

TC: That’s right. You will translate what the machine says and try to motivate people to do it. Professors and teachers will be more like coaches or tutors, rather than carriers of information. They’ll steer you to the program, tell you which classes to take, and be a kind of role model to get you excited about doing the work.

It’s a very important skill, and hard to learn. But I think you’ll see this kind of pattern again and again.

WF: How else do you see management changing?

TC: Management — for all the change we like to talk about — has actually been pretty static for a while. But smart machines and smart software are going to change management drastically, and in general we’re not ready for this. We will need truly new managerial thinking, not just new in the cliched sense of repackaging with new rhetoric and new categories.

WF: I wanted to ask you a little more about the machine-human teams. Freestyle chess — where human and computer teams play together, and outperform either on their own – is the example throughout the book.

What skills does the freestyle chess master have that the grandmaster doesn’t?

TC: The program, of course, does most of the calculations. The one skill the human needs when playing freestyle is how to ask the program good questions. Knowing what questions to ask is how you beat a solo program playing against you, and you don’t even have to be very good at chess. You need to understand chess at some core level, and you need to understand what different programs can and cannot understand.

It’s a kind of meta rationality. Knowing not to overrule the programs very much, but also knowing they’re not perfect, and knowing when to probe. And I think that, in management, those will be the important human skills.

WF: How do you determine where the line is between when the employee is able to add value above and beyond what computer intelligence is giving them, and when the software itself can replace them?

For example, I’m imagining some analytics software. Someone is very skilled at using it, they’re drawing some conclusions, they’re presenting them to people. But the next version of software may have built-in the ability to make those inferences. What skills keep that human from being replaced?

TC: People who can judge that there’s more to the matter than the software can grab; people who can judge the fact that there’s a need for a different kind of software for the problem; people who know when to leave the software alone and get out of its way.

Those are difficult to acquire and often quite intangible skills, but I think they’re increasingly valuable. You can think of other professional areas, like law or medicine, where you let the software do a lot of the work but you can’t uncritically defer to it. Software is bad at common sense in a lot of ways and it misses a lot of context. It’s people who can provide context.

WF: You have an interesting section in the book with respect to specialization in science. Do you see the path towards greater specialization as the path to career security? Or is there still a role for generalists?

TC: There’s a role for both, but you need to ask whether these terms lose some of their meaning. If someone says to you “I specialize in being a generalist,” it’s not actually a crazy claim. Most people cannot be a generalist, and you have to work really hard at a bunch of particular things to be good at it. You’re specializing in doing that. These are people who integrate and understand the contributions of others — that’s a lot like managing. So what you call generalists — I would not oppose them to specialists — there’s a big and growing role for them.

WF: You can’t go a day without seeing a story about who should learn to code or not learn to code. The same thing with respect to statistics. Given the way you see the labor market breaking out, are there specific things you advise people go out and learn?

TC: Statistics will be an increasingly big area. And even knowing a little can have a pretty high return. Coding’s tricky. If you can learn it, great. But if you can’t do it right, you really shouldn’t bother. There’s no half way.

But if you’re a manager or you work in health care, you might not ever be doing statistics, but if you can grasp some basic stuff that you can teach yourself, there’s a very high return. And it’s really quite feasible, unlike coding where it’s a major undertaking. If you’re a doctor trying to figure out which parts of the hospital are bringing in the money and someone hands you statistics — if you’re helpless, that’s really bad.

WF: One area that strikes me as one of the more difficult for machine intelligence is strategy. Where to position your business in a marketplace seems like on the far end of what machines can tell us.

TC: Yeah, that’s all humans, though you might consult machines for background information. But in no sense are machines close to being able to do that. That’s a very long way away.

All of our sectors are all on different paths, and the differential timing actually will be useful because we won’t have to figure it out all at once. We’ll get lessons from different areas sequentially and adjust. Humans will switch into the sectors they’re still good at in a rolling way. And that will make this socially more stable and better for most people.

If you woke up one morning and the machines were better than you at everything, that would be pretty disconcerting. That’s the science fiction scenario but it’s not that realistic.

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

How an Auction Can Identify Your Best Talent

The American Way of Hiring Is Making Long-Term Unemployment Worse

We Can Now Automate Hiring. Is that Good?

Learn How to Spot Portable Talent

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the January–February 2014 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the January–February issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Cartoon Caption Contest at the bottom of this post. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in next month’s magazine and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“Call me old-school, but if I don’t take notes in cuneiform, it goes right out of my head.”

Michael Shaw

Bob Eckstein

“I regret not taking management classes.”

Roy Delgado

And congratulations to our December caption contest winner, Kevin Thomas of Williamstown, Massachusetts. Here’s his winning caption:

“It still works in theory.”

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your own caption for this cartoon in the comments field below — you could be featured in next month’s magazine and win a free book. To be considered for the prize, please submit your caption by January 7, 2014.

Cartoonist: Paul Kales

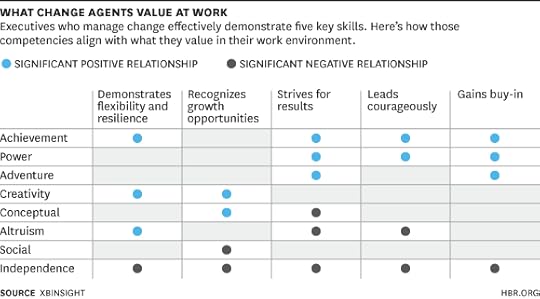

What Change Agents Value at Work

When it comes to change management, half the battle is making sure you have the right leaders in place. And that means looking carefully at their competencies, behavioral styles, and values.

To help with that challenge, my colleagues and I have created a change-agent profile. In our work assessing people for the right job fit, we’ve collected and analyzed extensive data on Fortune 1000 executives across a wide spectrum of industries. Here’s what we’ve discovered about change agents in that senior group:

They’re somewhat rare. Approximately 20 percent of senior executives scored high on five key competencies that correlate with effective change management.

Executives with those five competencies are more task-oriented than people-oriented.

They also appear to be motivated most by achievement. Power is a close second.

And here’s how we arrived at those high-level findings.

We analyzed competencies.

In our years of experience working with organizations in transition, we’ve identified the following strengths as key indicators of effective change management:

Demonstrates flexibility and resilience. Works well with a variety of individuals or groups. Adapts as the requirements of a situation change. Manages pressure and copes with setbacks effectively.

Recognizes growth opportunities. Looks for ways to improve. Demonstrates skill in minimizing others’ resistance to change.

Strives for results. Focuses on improving performance.

Leads courageously. Takes charge of initiatives and situations. Takes responsibility for making difficult decisions, even in the face of dissent. Shares feelings, opinions, and needs with clarity and conviction. Does not avoid conflict or differences.

Gains buy-in. Explores alternative perspectives and ideas to reach solutions that have support from others in the organization.

So after surveying more than 600 executives about their experiences dealing with a range of change-related business problems, we analyzed the data for statistical relevance to the competencies above.

We examined behavioral styles.

Next, we looked at the four behavioral styles from our own version of the DISC methodology personality assessment: driving (assertive, independent, driven to win, on the go), impacting (talkative, social, emotional, and spontaneous), supporting (empathic, accommodating, and trustworthy), and contemplating (reserved, analytical, quiet, and unhurried).

Even though the people-oriented “impacting” executives tend to implement change effectively, it turns out that the more task-oriented “driving” executives are even better at it. They score the highest, of everyone surveyed, on all five change competencies. They have a strong need to dominate, and they’re directive when they deal with problems. Decisive and results-focused, they are uncomfortable with the status quo and likely to be strong change agents.

We correlated competencies with values.

Finally, we looked at how executives with all five competencies scored on values, which helped shed light on the type of work environment they find most motivating and rewarding. We saw the strongest positive correlation with the desire for achievement, followed by the desire for power, adventure, and creativity, respectively. Leaders who scored high on independence and altruism tended to score lower on the five change competencies.

If your organization is facing transition, try evaluating people against our change-agent profile when hiring, assigning, or promoting them. During interviews, zero in on the key competencies, and ask how they’ve demonstrated the related behaviors in their current and previous roles. Further, ask yourself whether they show evidence of being task-oriented and are strongly motivated by achievement and power. The executives who do are the ones best equipped to make change happen.

The Seven Imperatives to Keeping Meetings on Track

There’s nothing more annoying than a meeting that goes on and on and on. As a manager, it’s your job to make sure people don’t go off on tangents or give endless speeches. But how can you keep people focused without being a taskmaster or squashing creativity?

What the Experts Say

The good news is that meeting management isn’t rocket science; you probably already know what you should be doing. The bad news is that keeping your meeting on track takes discipline, and few people make the effort to get it right. “The fact is people haven’t thought about how to run a good meeting, or they’ve never been trained, or they’re simply too busy,” says Bob Pozen, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School, senior fellow at Brookings Institute, and author of Extreme Productivity. “Organizations are moving faster and faster these days and few managers have time to think through their meetings in advance,” says Roger Schwarz, an organizational psychologist and author of Smart Leaders, Smarter Teams. But rushing now is only going to cost you more time later. So whether you’re getting ready for a weekly team meeting or convening a larger group to discuss your division’s strategy, it’s important to put in the effort. Here’s how to make your next meeting your most productive one yet.

Make the purpose clear

You can head off a lot of problems by stating the reason for getting together right up front. Schwarz recalls seeing a sign in a conference room at Intel’s headquarters that read: If you don’t know the purpose of your meeting, you are prohibited from starting. This is a wise rule. Send an agenda and any background materials ahead of time so people know what you’ll cover. Consider sending a list of things that won’t be discussed in the meeting as well. Schwarz suggests that you list agenda items as a question — rather than “Discuss video schedule” write “When will videos be completed?” to show what outcome you have in mind. Next to each item, you can also indicate participants’ roles — are they sharing information, contributing ideas, or making a decision?

Control the size

Meetings can get out of control if there are too many people in the room. “Chances are they won’t be attentive or take responsibility for what’s happening,” says Pozen. But with too few people, you may not have enough diversity of opinion. Only include those who are critical to the meeting. “Don’t feel you have to invite everyone who ever thought about the problem,” he says. “If you think someone might be offended, you can send out a memo and loop back with them afterward so they know what’s happening.”

Set the right tone

As a manager, it’s up to you to ensure that people feel comfortable enough to contribute. “You’re there to be a steward of all the ideas in the room,” says Schwarz. Set the right tone by modeling a learning mindset. Instead of using the time to convince people of your viewpoint, be open to hearing other’s perspectives. Explain that you don’t have all the answers, nor does anyone else in the room. Be willing to be wrong. Schwarz says you want “participants to see the team meeting as a puzzle — their role is to get the pieces out on the table and figure out how they fit together.”

Manage ramblers

“People often give speeches instead of asking questions,” says Pozen. It’s tough to cut a rambler off, but sometimes it’s necessary. Schwarz suggests saying, “OK, Bob, you’re absolutely right and is it ok if we talk about that later?” Getting his buy-in will ensure that he doesn’t return to his speech at the next opportunity. For someone who is prone to long-windedness, talk with her ahead of time or during a break, and ask that she keep her comments to a minimum to allow others to be heard.

Control tangents

Sometimes it’s not that an individual goes on too long but he raises extraneous points. “If two or three people bring up things that are contiguous but not really related, the meeting can degenerate,” says Pozen. Try to refocus them on the stated agenda. On occasion, someone may intentionally go on a tangent. Maybe he feels territorial about a decision you’re making or is unhappy with the direction you’re taking the conversation. “Rather than accuse the person of trying to derail your meeting, ask what’s going on. Pozen suggests you say something like, “You’ve diverted us several times. Is there something’s that bothering you?” Addressing the underlying issue head on can help appease the dissenter and get your meeting back on topic.

Make careful transitions

“Typically leaders go from topic to topic, moving ahead when they’re ready to,” says Schwarz. “But people don’t always move with you and they may get stuck in the past.” Before you transition from one agenda item to another, ask if everyone is finished with the current topic. “You need to give people enough air time,” says Pozen. This will help keep the conversation focused.

End the meeting well

A productive meeting needs to end on the right note to set the stage for the work to continue. Pozen suggests you ask participants, “What do we see as the next steps? Who should take responsibility for them? And what should the timeframe be?” Record the answers and send out an email so that everyone is on the same page. This helps with accountability, too. “No one can say they’re not sure what really happened,” says Pozen.

Principles to Remember

Do:

Make the meeting purpose clear and send an agenda out ahead of time

Talk to anyone who might monopolize meeting time before you get in the room and ask him to keep comments to a minimum

Send out a follow-up email after the meeting that lists next steps, who’s responsible for them, and when they’ll get done

Don’t:

Feel obliged to invite lots of people — only include those who are critical to making progress

Move on to a new topic until everyone feels they’ve been heard

Let the group get distracted by tangents — ask if you can address unrelated topics another time

Case study #1: Let everyone be heard

As the vice president of maintenance, repair, and overhaul at American Airlines, Bill Collins was tasked with improving the company’s relationship with unionized workers. To help facilitate conversation, Bill set up town hall-style meetings with Tulsa operation’s 6,500 employees. He quickly realized that these gatherings weren’t efficient or productive. “There hadn’t been town-hall meetings in 15 years and people had a lot of pent up anxiety that they wanted to get off their chests. They wanted to hang me,” he says. The meetings were scheduled for one hour but often lasted two.

Bill decided to make some changes. First, he made the meetings smaller by dividing them up by business and shift so that each only had about 250 people. “They still wanted to hang me but as least the conversation was manageable,” he says. Second, he changed the tone of the meeting by opening with a proposed agenda and asking for input. “I’d say, ‘Here’s what we want to discuss. What do you want to discuss?’” And if someone wanted to talk about something that wasn’t on the agenda, Bill would respond, “We’ll go to any level of detail you’d like on that topic during the Q&A. Is that OK?” He’d then wait for at least a head nod before moving on.

When Bill first described this approach to his fellow executives, many expressed concern that the meetings would take even longer if everyone had the chance to be heard. But he was invested in making it work. “The natural tendency for the workforce is to not trust management,” he says. “This process builds trust.” And, after the first of these newly revamped meetings, he had the proof he needed. “There were no raised voices,” he says. “It was calm, cordial, and it ended well. Leaders of the local union said it was the best meeting they’d been to.”

Case study #2: Actively manage disrupters

When Betsy Stubblefield Loucks took over as executive director of HealthRIght, a nonprofit focused on healthcare policy in Rhode Island, one of her responsibilities was to convene a monthly meeting with 20 people from various organizations with a stake in healthcare reform, such as labor, hospitals, insurers, and consumer advocates. The goal was to problem-solve and reach agreement about how the organization should approach different aspects of reform. In the past, the meetings were structured around specific topics but they didn’t have stated outcomes or a process for reaching resolution. As a result, participants would often just talk about issues they cared most about. “People had hot button issues and would make speeches about them,” she says.

Betsy decided to do something different with the agenda; she put the desired outcomes for each meeting at the top. This helped focus the conversation. She also made an effort to build relationships with people who tended to dominate the conversation. “Health care reform is a very broad — and deeply sensitive — topic. Our members are very passionate about their issues, and some people would have the same debates over and over because they didn’t feel heard,” she says. She set up meetings with these participants in advance of the monthly coalition meeting to let them vent to her personally and check her understanding of their perspective. Then when the group was together, she would represent that person’s opinion — with their permission — in a more concise way.

For particularly difficult people, she would assign someone to actively manage them during the meeting. “There was one person who would give the same stump speech over and over,” she says. So she asked a member of her executive committee to sit next to him, and when he started going on, to interrupt him. The executive committee member did this respectfully saying, “I think you’re making a great point,” and then would summarize his perspective. This helped the rambler feel like his point had been understood. It also helped Betsy keep focused on the meeting. “That way I wasn’t the only one playing traffic cop and he didn’t have to get mad at me,” she says.

Betsy uses these same approaches in smaller meetings as well. “Anytime I meet with more than one other person, I use these tactics. When I have the right people in the room, send out a clear agenda, and talk to any difficult people in advance, my meetings go much more smoothly,” she says.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers