Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1489

December 30, 2013

The Flow of U.S. Manufacturing Jobs Now Goes Both Ways

Over the past four years, companies have created more than 80,000 manufacturing jobs in the U.S. by moving production to America from abroad, according to a Wall Street Journal report that cites figures from the nonprofit Reshoring Initiative. The U.S. continues to lose manufacturing jobs to offshore plants, but those losses are now being offset by inflows. An example is Whirlpool, which is moving some of its washing-machine production to a plant in Clyde, Ohio, from one in Monterrey, Mexico, mainly to take advantage of lower energy and product-transportation costs.

Why Talking About Employee Poverty Makes Us Uncomfortable

Earlier this month, I asked a simple question about an apparent change in the social contract at work: Do employers care if their employees are paid so little that they require government assistance to get enough to eat?

The response was overwhelming — close to 600 comments on the HBR website, and the discussion was picked up by The Huffington Post, MSNBC, and other outlets.

What can we learn from those comments about the answer to that question?

We might expect that the readers of HBR are interested in and sympathetic to the problems facing businesses that directly affect the average person. Given that, it may be surprising that a majority of the comments thought that employers were wrong to pay poverty-level wages. But there were also many who did not believe that such low wages were a moral dilemma for companies paying them, and their arguments fell into three general categories.

One camp simply denied that low-wage workers and their families are truly in need, typically based on heroic assumptions about how little it actually costs to live. Whether or not we personally believe these workers are poor enough to merit attention, however, the U.S. government has determined that the roughly 10 million working poor are paid too little to make it without government help.

A similar assertion was that the working poor are there by choice. It is certainly true that individual responsibility has a profound influence in determining one’s life circumstances, but the idea that poor workers could solve their financial needs themselves by moving up to better jobs represents a fallacy of composition: Yes, a low-wage worker who really applies themselves can probably move up to a better job, but there are nowhere near enough of those better jobs for every low-wage worker to get one. The commentators who feel that they pulled themselves up by their own bootstraps should be the most aware of how difficult that was to do, and if they are honest, they also know that different circumstances could have stymied them as well.

The third theme was to assert that employers do not have any moral responsibility for what their employees are paid. A crude version of this argument is that employees are just like any other commodity and that squeezing down their costs was a perfectly acceptable thing to do. As someone who has studied human resources for decades, I have never met an employer who actually held this view. Employers want their employees to look after the interests of the business, and it is almost impossible to secure that behavior with an approach that says, “We have no responsibility to you.” As my colleague Christopher Kulp notes, even if one believes that business has no responsibility to employees, employers are people, too, who are also citizens, parents, and community members. In those roles, it would be surprising if they did not care about poverty, whatever the cause.

Clearly, these three assertions do not hold up to careful scrutiny, and it is tempting (and concerning) to see them as efforts to rationalize away uncomfortable facts.

The last argument in particular does not deny that low wages are a problem, but asserts that in practice, there is nothing that employers can do about that because low-wages are simply the result of the market, and tampering with the market will cause worse problems: Higher wages will lead to layoffs, inflation, and businesses failing.

If business success is that sensitive to wages, then employers have been getting quite a break in recent decades, because the minimum wage has declined about 40 percent in real terms since its peak value in 1969. Earnings for the hourly paid in general have also declined since their peak in 1972, about the point when wage increases stopped keeping up with productivity increases. On the other hand, wages have been rising sharply for executives and managers, and commentators have not complained that these increases would kick off inflation, cause layoffs, or force companies out of business.

Nevertheless, it is certainly true that there is no free lunch and that higher wages — no matter who gets them — have to be paid for in some way. It is also true, though, that there are benefits to individual employers who pay higher wages. Paying more gets better workers with lower turnover and better job performance, which offset some or perhaps even all the costs of higher wages. Given this, it is surprising how few employers seem to ask themselves whether they would be better off paying their low-wage workers more.

If all employers raised their wages for low-paid jobs, many of the benefits of being a better employer would go away. But so too would the potential problem of having higher costs than competitors — after all, most low-wage jobs are in retail, hospitality, and food service, where there is no foreign competition. And when it comes to the argument that higher wages would lead to layoffs en masse, my read of the evidence on changes in minimum wages, which raise the floor for all employers, is that any effects are small: a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage reduces jobs for low-paid workers by maybe one percent.

In the end, we are left to ponder why so many successful companies set pay so low that their employees need government assistance to eat. At least part of the cause has to be decisions made inside companies. What changed in the companies over time to make this happen? Perhaps this is a question that does not get asked because the answers are uncomfortable.

December 27, 2013

Out with the Old (but Really Great Business Stories), in with the New

For a few days last August, it was one of the most talked-about business stories in America: Tim Armstrong, the CEO of AOL, fired someone abruptly during a meeting. A recording of the incident went viral. What made the typically affable Armstrong snap? In this massive piece, Nicholas Carlson analyzes Armstrong's rise from his days as the owner of a strawberry business, uncovering a leadership trajectory that culminated in a proxy war with an activist investor and a final realization that his baby — local-news and listings provider Patch — needed to be trimmed, or else.

Armstrong told his board he could make Patch profitable within a year, but it didn’t happen. Last August, feeling awful, he knew he had to face the consequences and make unpopular choices. "For so long, it was a price he had never had to pay," writes Carlson, and offers ample evidence that the exec was more comfortable in the role of the golden boy than of the guy who had to make tough decisions. Eventually, Armstrong became so emotional about doing the latter that it didn’t take much to provoke him. And we all know what happened next. (October 2013)

The Dark Side of Generic Drugs Dirty Medicine Fortune

Generic drugs can be inexpensive and effective alternatives to their branded counterparts. But according to this devastating Fortune investigation, they can also be useless on a good day and deadly on a bad one — that is, if they were manufactured by Ranbaxy, an Indian drug maker. In this epic piece, Katherine Eban uncovers downright fraud in how generics were tested (or, rather, weren't) and exposes a corporate culture so steeped in greed and dysfunction that fistfights were known to break out during executive meetings. Although concerned employees tried to alert the FDA and other regulatory agencies to the company's behavior, progress in stopping the distribution of potentially dangerous medications crawled along at a turtle's pace. Sure, the company was eventually both punished and sold (it’s now one of the fastest-growing pharmaceutical businesses in the U.S.). But when FDA inspectors were asked whether they would be comfortable taking a Ranbaxy-made drug, such as a generic cholesterol medication, "like eight out of eight" said no. (May 2013)

Lunchables Are All About PowerThe Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk FoodNew York Times Magazine

The success of Lunchables derives from a combo of a high-fat food and a message that is "about kids being able to put together what they want to eat, anytime, anywhere." Oh, and: the optimal crunching pressure of a potato chip for is four pounds per square inch. This New York Times Magazine piece by Michael Moss is packed with such details, which I found just as addictive as a bag of Lays. In it, he traces the intersection of science and marketing that's made junk food so delicious, so profitable, and so very bad for you. The story starts at a secret meeting among the CEOs of America's largest food companies in 1999, at which some execs tried to veer the industry along a healthier path (using the dreaded comparison of Big Tobacco), only to be shut down by the head of General Mills. What comes next is a detailed look at how brands like Dr Pepper, Oscar Mayer, and Frito-Lay hired sought-after experts to make their food taste just so, combining the taste perfection with psychologically effective marketing. (February 2013)

By the People, Not For the PeopleMaximizing Shareholder Value: The Goal That Changed Corporate America The Washington Post

In 1963, IBM CEO Thomas J. Watson published A Business and Its Beliefs: The Ideas That Helped Build IBM. The text listed the company's values in the following order: respect for the employee; a commitment to customer service; and achieving excellence. By 1994, when Louis V. Gerstner Jr. headed the company, he orchestrated an epic turnaround, putting shareholder value and customer satisfaction at the top of the list. Employees and community were at the bottom. The most recent two CEOs placed investor returns at the top of their priority lists.

So how did the company go from extolling and supporting employees to slashing jobs in order to make money for its shareholders? Jia Lynn Yang explores this trajectory, focusing on the 1970s explosion of free-market scholarly thought that has become the baseline for running a company in the twenty-first century. This, of course, has led to the implicit notion that CEOs work for the short-term benefit of their investors, not their employees, and will be rewarded with piles of cash and stock options in the process. But is it actually working? Many people, it seems, are concerned that we've adopted a mantra as fact without considering its long-term consequences for the health of the American workforce. (August 2013)

When a Website Literally CrashesThe Strava Files Bicycling Magazine

What responsibility does the maker of a fitness social network have for the safety of its users — and the general public? This lengthy investigation by David Darlington takes a close look at Strava, one of biking's most successful sites and apps, which does exactly what a good social tool should: It allows you to track your athletic progress and compare it with others’, all the while tapping into curiosity, self-interest, and social competition — three of the brain's chief dopamine drivers. But after two people died in connection with the site — a cyclist was killed while attempting to reclaim what's known as King of the Mountain [KOM] status as the fastest rider for a given route, and a pedestrian was struck and killed by a speeding biker two years later — the cycling, start-up, and legal communities were forced to take a close look at whether Strava was creating and reinforcing competition at society’s peril. I won't give away the end of the piece, which involves a potential legal nightmare for any company that asks users to hit an "Agree" button after reading terms and conditions. But the Strava case is prescient as we continue to develop digital technologies that influence the emotions and impulses that make us so darned human. (October 2013)

Nice Try, Though You Didn’t Make the Harlem Shake Go Viral — Corporations Did Quartz

Remember the Harlem Shake? It doesn't have much to do with Harlem, according to real people who actually live there, and it doesn't have much to do with the power of crowdsourced virality either. In this smart takedown of the meme, Kevin Ashton recreates the timeline of the dance's popularity to reveal exactly how, in the wake of Oreo's Super Bowl "win," corporations pounced on the video's potential to make money. The Harlem Shake itself, writes Ashton, "originated with a drunken man named Albert Boyce dancing at Harlem’s Rucker Park basketball court in 1981." It then inspired an unsuccessful song, until a student named George Miller used it in a video. A few people copied him, and a version found its way onto Reddit, which prompted someone at Maker Studios to recognize its "pre-viral" potential. So began its "rapid replication," which "was driven by media and marketing professionals, led and orchestrated by three companies: Maker Studios, Mad Decent, and IAC." And as more people clicked, money flowed from Google's ad structure, "where more searches and more views mean more dollars." (March 2013)

You'll Never Buy Anything the Same Way AgainThe Secrets of Bezos: How Amazon Became the Everything Store Businessweek

Ever wondered what it's like to work at Amazon? Or to be one of its competitors or potential acquisitions? Or even to be related to founder Jeff Bezos? Look no further than this lengthy piece by Brad Stone. On my first question, Bezos isn't a particularly nice boss. Amazon's culture is "notoriously confrontational," with Bezos regularly embarking on what employees call "nutters," which largely consist of him shooting off phrases like "Are you lazy or incompetent?" "I'm sorry, did I take my stupid pills today?" and "If I hear that idea again, I'm gonna have to kill myself." And yet many people who work there thrive in this environment and generally find that Bezos is right on target when he flippantly dismisses an idea or prioritizes a customer complaint over being civil to his underlings. As for my second and third questions, you're going to have to read the article. In particular, what happens when Stone tracks down Bezos's biological father is astonishing. (October 2013)

BONUS BITSDon't Fret! Here are Some Brand New Stories, Too

The Corporate "Free Speech" Racket (Washington Monthly)

Jesse Willms, the Dark Lord of the Internet (The Atlantic)

The Shape of Things to Come (Foreign Affairs)

To Optimize Talent Management, Question Everything

Should you hire as if your workforce will stay a month, a year, or their entire career? The answer makes a big difference in the qualifications you set, how well candidates must “fit” with the job, the team or the organizational culture, and the “deal” you offer. A traditional employment model may work for some, while a model based on short-term employment may work for others. At the extreme, it may be best never to “hire” your workers at all, or to “fire” and “hire” them several times. Leaders need solid principles to build talent strategies that fit the situation, with an optimization approach. Too often the necessary principles for optimization are lost in the chorus of divergent views and pithy examples. This chorus can also obscure the need to question long-held assumptions. Letting go of those assumptions may be the key to seeing new options that make optimization possible.

To see examples of the dilemma, you need look no further than this website and its Insight Center on Talent and the New World of Hiring. The website features a blog by Wharton labor economist Peter Cappelli, suggesting that U.S. companies return to the “Organization Man” model, right next an article by Reid Hoffman (cofounder of LinkedIn), Ben Casnocha and Chris Yeh, three entrepreneurs who say that the 20th century compact is gone, and instead recommend short-term “tours of duty.”

Cappelli states, “Is it time to bring back the Organization Man? In that model, which drove the US economy for most of the last century, employers made longer-term commitments to employees, where they invested in development to fill jobs, and where employees responded with commitments of their own in terms of performance. Jobs were filled internally with people prepared to do them, skill shortages were unknown, and employees were engaged with the needs of their employer,” and concludes, “what won’t work is pursuing this model half way, giving some employees some development opportunities but then still filling more senior vacancies from the outside. Why would someone wait around if it looks as though opportunity will not come?”

Hoffman and colleagues argue just as passionately that employment contracts should carry a short and defined endpoint (two to four years), “An employee who is networking energetically, keeping her LinkedIn profile up to date, and thinking about other opportunities is not a liability. In fact, such entrepreneurial, outward-oriented, forward-looking people are probably just what your company needs more of.” They imply that contracts could have different features for different employees and that encouraging employees to leave and return may be preferable to having them waiting around.

These are just two examples. They are widely divergent views, each punctuated by compelling examples, and each potentially optimal, but only for some situations. Of course, organizations need future skills and workers may desire predictability in their development. But fast-changing global product and labor markets can make it prohibitively risky for any organization or individual to try to see that far ahead. What will drive a more “optimal” decision framework?

It will require emancipation from fundamental assumptions, such as “employment” and “organization.”

“Employment” will not be the only way organizations engage people. You can already see this in internet-based labor brokers such as oDesk, which deconstruct projects into small components and match each component to a contractor who will never be employed by the organization. Crowdsourcing routinely gets work done by people who never even get paid, let alone become employees. Even when people do become “employees,” trends suggest shorter tenure, lower loyalty and employment “deals” designed to last just a few years. Once you rethink the idea of employment as the engagement model, the options for optimal hiring expand immensely.

The “organization” or “corporation” will not be the only collaboration model. Alumni networks allow rehiring former employees after they gain valuable experience in other organizations. In Transformative HR, we described Khazanah Nasional, a Malaysian Government investment body, which brokers well-structured “trades” of future leaders among companies, to build more well-rounded future leaders as a national resource. Also, the concept of an “organization” hardly applies to the community of video gamer volunteers that solved a riddle about the structure of the AIDS virus, which had eluded organizational R&D scientists.

We need a useful and lively debate about the future of hiring, and the future of work that it represents. No doubt optimal solutions will be as diverse as the Organization Man and Tours of Duty. Yet, the answer to optimized talent management requires more, including questioning assumptions. Savvy leaders will avoid being too quick to jump from one pithy example to another, and instead question assumptions to find the solutions that will optimize their choices.

Talent and the New World of Hiring

An HBR Insight Center

Make Sure Your Dream Company Can Find You

Never Say Goodbye to a Great Employee

What Boards Can Do About Brain Drain

How an Auction Can Identify Your Best Talent

The Secret to Delighting Customers

What motivates employees to go above and beyond the call of duty to provide a great customer experience? Disney tells a story about a little girl visiting a theme park who dropped her favorite doll over a fence. When staff retrieved the doll, she was covered in mud, so they made her a new outfit, gave her a bath and a hairdo, and even took photos of her with other Disney dolls before reuniting her with her owner that evening. The girl’s mother described the doll’s return as “pure magic.”

The theme park team didn’t consult a script or seek advice from managers. They did what they did because going the extra mile comes naturally at Disney. Such devotion to customer service pays dividends. Emotionally engaged customers are typically three times more likely to recommend a product and to repurchase. With an eye to these benefits, many companies are making customer experience a strategic priority. Yet they are struggling to gain traction with their efforts.

Why is customer experience so difficult to get right? The main hurdle is translating boardroom vision into action at the front line. That’s even more important in an era when optimizing individual customer touchpoints is no longer enough —when you have to focus on holistic customer journeys, instead.

There’s only one way to create emotional connections with customers: by ensuring every interaction is geared to delighting them. That takes more than great products and services — it takes motivated, empowered frontline employees. Creating great customer experience comes down to having great people and treating them well. They will feel more engaged with the company and more committed to its goals.

The best companies make four activities habitual:

Listen to employees. Want your employees to take great care of your customer? Start by taking great care of them. Treat them respectfully and fairly, of course, but also get involved in tackling their issues and needs. Establish mechanisms to listen to concerns, then address them.

When Disney first opened its Hong Kong resort, employees had to pick up their uniforms from attendants before every shift. With up to 3,000 people arriving at once, waiting in line could create frustration and delay. So leaders responded by pioneering a new approach using self-service kiosks. Employees pick up a uniform, scan the tag and their ID at a kiosk, check the screen display, and walk away. Result: a smoother start to the day that frees frontline staff to focus all their energies on customers. The new approach was so effective that Disney rolled it out across all of its parks and cruise ships.

Hire for attitude, not aptitude — and then reinforce attitude. To get friendly service, hire friendly people. Airline JetBlue has embedded this philosophy in its hiring process. To recruit frontline staff with a natural service bent, it uses group interviews. Watching how the applicants interact with one another enables hiring managers to assess their communication and people skills to an extent that wouldn’t be possible in a one-to-one setting.

Having hired people with the right attitudes, leaders need to ensure they reinforce the behaviors they want to see. Although Disney hires janitors to keep its parks clean, everyone else in the organization knows that they share the responsibility for maintaining a clean and pleasant environment. Asked why he was picking up paper in the restroom, one leader replied, “I can’t afford not to.” Leaders’ actions are visible to all. Or as Disney puts it, “Every leader is telling a story about what they value.”

Give people purpose, not rules. Rules have their place, but they go only so far. To motivate employees and give meaning to their work, leading companies define their “common purpose”: a succinct explanation of the intended customer experience that resonates at an emotional level. When people are set clear expectations and trusted to do their jobs, they feel valued and empowered. They choose to go that extra mile through passion, not compliance.

For Chilean bank BCI, common purpose is about developing trust-based customer relationships that last a lifetime. Leaders at the bank tell a story about a lottery winner who was deciding who to entrust with his prize money. Asked why he chose BCI, he said advisors didn’t just sell him products, but tried to satisfy his needs. Some of them traveled regularly on the bus he drove, and he thought they seemed just as genuine in their free time as they were in the branch.

Tap into the creativity of your front line. Giving frontline employees responsibility and autonomy inspires them to do whatever they can to improve the customer experience. When they see a problem, they fix it without waiting to be asked. Frontline staff are also a rich source of customer insights. They can help leaders understand what customers want without the time and expense of market research.

Take Wawa, a US convenience-store chain. One enterprising manager decided his customers would like a coffee bar and a bigger choice of fresh food. When customer traffic and profits soared, head office noticed and dispatched a team to find out why. With facts in hand, the company quickly developed a plan to replicate the innovation across its network.

Technological advances have made it much easier for companies to understand customers on an individual basis. Even so, engaging with customers is still undertaken largely through personal contact. Building a relationship of trust happens at the front line, one interaction at a time. So to create an emotional bond with your customers, start with your employees.

Why Small Businesses Aren’t Hiring… and How to Change That

Despite the economic progress driven by business performance since the recession, the country has not recovered jobs at the same pace. Job growth, while improving, is slow by post-recession standards: The New York Times reported last year that percentage change in payroll, from business cycle trough to business cycle peak, averaged from all previous recessions, is 15%. For the current recovery it is 2%. By contrast, in an average recovery, corporate profits rise 38 percent from trough to peak. In this recovery, they have risen 45 percent. We have better than average profitability and much, much lower than average job growth.

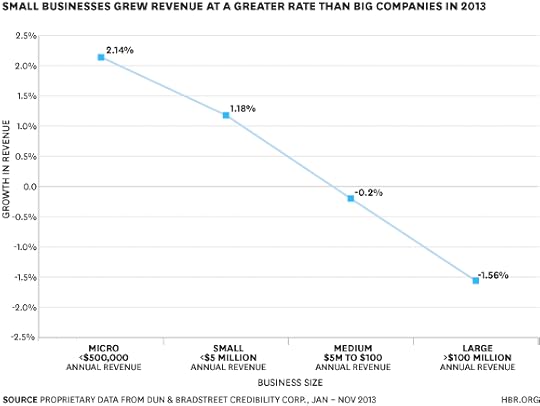

For their part, small businesses are growing revenues faster than larger businesses. D&B Credibility Corp. proprietary data shows that the smallest businesses have been growing revenues the fastest: In 2013 alone, micro business revenue on average grew by 2.14% while small business revenue grew by 1.18%. Yet medium business revenue stayed relatively flat, losing 0.2% overall. The large businesses on average in our data decreased revenue by 1.56%. (Microbusinesses are defined as those earning less than $500,000 in annual revenue, small businesses earn less than $5 million, medium-sized businesses earn between $5 million and $100 million, and large businesses earn over $100 million.)

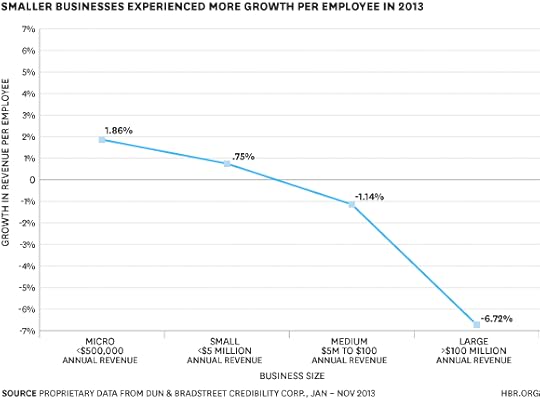

While the smallest businesses are growing revenues the most quickly, they are adding jobs the most slowly: From January to November 2013, micro businesses experienced 1.86% growth per employee, small businesses 0.75%, medium businesses -1.14%, and large businesses -6.72%. Strong sales and greater productivity, without employment growth, yields a jobless recovery.

Why aren’t successful small businesses adding more jobs?

We tend to equate job growth with business success but the reality is far more nuanced than that. Adding jobs is a capital investment, not a cash flow issue. In other words, crude as it may sound, additional employees are hired for future growth, similarly to the way business owners purchase computers, software, and other capital goods. For large businesses, the cost of employment is relatively low, so this point becomes largely academic. As revenues and profits rise, the largest businesses simply dip into their capital reserves to hire more people and grow their businesses. But small businesses do not have reserves significant enough to support new employment growth. It is a far bigger investment for a small business to hire an additional employee than for a larger business to do so.

Today, access to capital for small businesses is a significant problem. The largest businesses are able to secure financing with relative ease and on strong terms, including historically low interest rates. But as business size gets smaller, access to capital shrinks dramatically. For example, a recent Pepperdine University study showed a large discrepancy in bank loan approval rates: 75% of medium-sized businesses that sought a bank loan were successful, compared with 34% of small businesses and only 19% of microbusinesses.

Without capital, small businesses are not in a position to increase employment. This explains why even though small businesses have increasing revenues and remain optimistic, they are still not adding jobs.

This is alarming because small businesses drive economic recoveries. They not only employ almost half of the private sector, but they are also responsible for the lion’s share of new jobs created. In the past 20 years, about two-thirds of all net new jobs were created by small businesses. SBA data show that small businesses (those with 500 or less employees) amount to 99.7% of all businesses and employ 49.1% of private sector employment. Clearly, small business job growth is critical after a recession.

It’s not that the banks aren’t lending. Banks actually increased large business loans (defined by the FDIC as loans over $1 million) by 23% from 2007 (pre-recession) to 2012 (post-recession). Unfortunately they decreased small business loans (defined by the FDIC as loans $1 million and under) by 14% during the same time period.

In 2011, Vice President Biden and former U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) Administrator Karen Mills announced that 13 of the nation’s largest banks would increase small business lending by $20 billion over three years. In September, the SBA announced that the banks had already increased their small business lending by $17 billion, putting them on track to meet their goal by the end of 2014. This is great news, but there is a caveat. The banks were allowed to form their own definition of “small business.” And many of the banks consider a small business as having up to $20 million in revenues. And there is incentive for banks to lend towards the higher end of the scale.

In general, the larger the business, the less likely it is to default. Hence, banks tend to focus on lending to larger businesses. The government has tried to stem this trend with positive results by providing backstops through the Small Business Administration. (The SBA currently guarantees 85% of the value of loans up to $150,000 and 75% of the value of loans of more than $150,000.) While this has had a positive effect on small business lending, there may be greater benefit in having that distinction be focused, not on loan size, but on business size. For example, the SBA could guarantee 85% of the loan value for microbusinesses, 75% for small businesses, 50% for medium-sized businesses, and zero for larger companies. This would effectively tier the risk for banks and incentivize them to lend to the smallest businesses.

Businesses at every stage, whether start-ups or the largest companies, need access to capital to grow, but the risks of lending that capital vary widely. If the SBA were used to level the playing field, more small companies could get the access to capital they need to add jobs.

For more about this topic, see my testimony given before the House of Representatives Committee on Small Business on December 5, 2013.

The Unionization-Inflation Connection

In a study of inflation peaks that preceded monetary-policy adjustments in 21 nations between 1974 and 2004, Tony Caporale of the University of Dayton found that higher peaks were linked with higher levels of unionization. Specifically, a 1-standard-deviation increase in the percentage of public and private employees who were members of unions was associated with an 8.5% higher inflation rate at the peak before monetary adjustment. High levels of unionization can lead to wage inflexibility, which can contribute to consumer price increases.

Should Leaders Focus on Results, or on People?

A lot of ink has been spilled on people’s opinions of what makes for a great leader. As a scientist, I like to turn to the data. In 2009, James Zenger published a fascinating survey of 60,000 employees to identify how different characteristics of a leader combine to affect employee perceptions of whether the boss is a “great” leader or not. Two of the characteristics that Zenger examined were results focus and social skills. Results focus combines strong analytical skills with an intense motivation to move forward and solve problems. But if a leader was seen as being very strong on results focus, the chance of that leader being seen as a great leader was only 14%. Social skills combine attributes like communication and empathy. If a leader was strong on social skills, he or she was seen as a great leader even less of the time — a paltry 12%.

However, for leaders who were strong in both results focus and in social skills, the likelihood of being seen as a great leader skyrocketed to 72%.

Social skills are a great multiplier. A leader with strong social skills can leverage the analytical abilities of team members far more efficiently. Having the social intelligence to predict how team members will work together will promote better pairings. Often what initially appear to be task-related difficulties turn out to be interpersonal problems in disguise. One employee may feel devalued by another or think that she is doing all the work while her partner loafs – leading both partners putting in less effort to solve otherwise solvable problems. Socially skilled leaders are better at diagnosing and treating these common workplace dilemmas.

So how many leaders are rated high on both results focus and social skills? If this pairing produces especially effective leaders, companies should have figured this out and promoted people to leadership positions accordingly, right? Not hardly. David Rock, director of the Neuroleadership Institute, and Management Research Group recently conducted a survey to find out the answer. They asked thousands of employees to rate their bosses on goal focus (similar to results focus) and social skills to examine how often a leader scored high on both. The results are astonishing. Less than 1% of leaders were rated high on both goal focus and social skills.

Why would this be? As I describe in my book, Social: Why our brains are wired to connect, our brains have made it difficult to be both socially and analytically focused at the same time. Even though thinking social and analytically don’t feel radically different, evolution built our brain with different networks for handling these two ways of thinking. In the frontal lobe, regions on the outer surface, closer to the skull, are responsible for analytical thinking and are highly related to IQ. In contrast, regions in the middle of the brain, where the two hemispheres touch, support social thinking. These regions allow us to piece together a person’s thoughts, feelings, and goals based on what we see from their actions, words, and context.

Here’s the really surprising thing about the brain. These two networks function like a neural seesaw. In countless neuroimaging studies, the more one of these networks got more active, the more the other one got quieter. Although there are some exceptions, in general, engaging in one of the kinds of thinking makes it harder to engage in the other kind. Its safe to say that in business, analytical thinking has historically been the coin of the realm — making it harder to recognize the social issues that significantly affect productivity and profits. Moreover, employees are much more likely to be promoted to leadership positions because of their technical prowess. We are thus promoting people who may lack the social skills to make the most of their teams and not giving them the training they need to thrive once promoted.

How can we do better? For one, we should give greater weight to social skills in the hiring and promotion process. Second, we need to create a culture that rewards using both sides of the neural seesaw. We may not be able to easily use them in tandem, but knowing that there is another angle to problem solving and productivity will create better balance in our leaders.

Finally, it may be possible to train our social thinking so that it becomes stronger over time. Social psychologists are just at the beginning stages of examining whether this kind of training will bear fruit. One exciting prospect, one that would make the training fun, is the recent finding that reading fiction seems to temporarily strengthen these mental muscles. Wouldn’t that be great — if reading Catcher in the Rye or the latest Grisham novel were the key to larger profits?

December 26, 2013

Where There’s a Why, There’s a Way

At least once a week, I hear my son, a junior in high school, say, “What is the point of school? I am never going to use [insert subject] again.” He may or may not, depending on his chosen profession. My counter-argument tends to be, “You may not use all of it. Some of it you will. Regardless, good grades get you into college, and knowing how to work gets you into a happy life.” On days when I’m desperate, or just exasperated, I huff (and I puff): “Do it because I said to.” At which point I lament aloud, “Why doesn’t he have a vision for what his future might hold?”

In her provocative piece, “The Last Thing You Need Is Vision,” Jesse Lyn Stoner explores the question of whether vision is overrated. Her conclusion: in the case of a foundering business, you may need to start with clearing the decks and patching the leaks, but ultimately, you can’t expect to get anywhere without a vision. Her piece started me thinking about the discovery-driven approach I emphasize in my work on dreaming and disrupting, versus embracing a vision at the outset.

Disruption is, by its very nature, discovery-driven. You can’t see the end from the beginning when you play where no one else is playing — so you simply start. You move out of your comfort zone, away from the known, and at every step you have to stop, reevaluate, and recalibrate your course. “Vision” implies you have a view of exactly where you want to go and you chart a course accordingly, like plotting a journey on a map, a straightforward road with no distractions, roadblocks or alternate routes.

So what place does vision have in the midst of disruption? When you are young, or when your why is non-existent or has gone missing, which happens to most of us at some juncture in our business or career, it may be that you just need to move forward. Or as David Brooks has written, “most people don’t form a self and then lead a life. They are called by a problem, and the self is constructed gradually by their calling.”

Despite these realities, I’ve come to believe that vision is imperative to staying the course when disrupting. A would-be disruptor who hasn’t defined their “why” will easily be enticed back into the safety of the known. Compare Abraham Lincoln to Ulysses S. Grant, says negotiating expert Jim Camp. Lincoln had a vision of saving the Union at any cost. As a general of the Union troops, Grant hewed without hesitation to Lincoln’s vision. “But as a president, Grant was a failure, taking bad advice, making bad decisions, mainly because he didn’t know why he was president and what he hoped to accomplish.” If you don’t have a powerful answer as to why you are disrupting, you can easily get distracted and lose your way. Paraphrasing Proverbs, Where there is no vision, we really do perish.

Trish Costello, founder of Portfolia, knows her “why”: assist starts-up in growth and financing. Her “how” has morphed over the past two decades. Costello founded and led for twelve years the prestigious Kauffman Fellows program, one of the world’s most respected private training programs for venture capitalists. Then, in 2013, she launched Portfolia, a platform that allows start-ups to raise money from the crowd, whether family, friends, or professional investors. Different methods, same purpose.

Salesforce.com founder Marc Benioff also displays a clear why: make it easier to serve the customer. CRM started as a simple-to-use, cloud-based (read: low cost) sales data warehouse. His “why” intact, but with a change in “how,” Benioff launched Chatter in 2010, a platform that supported collaboration within the enterprise – to better serve customers. Then in 2013, he made a big gamble on a how. He allocated 50% of his software development time to make Chatter the primary interface (analogous to the Twitter and Facebook activity streams) in Salesforce.

I’ve been grappling with this personally, as I have pursued two important goals for 2014: to run a marathon and to organize a conference on pursuing dreams. Both goals spring from my “why”: I want to make it possible for individuals everywhere, including myself, to dream big and actually start taking steps toward realizing their dreams – especially the dreams that seem unattainable. Before last year’s Boston Marathon bombing, I didn’t consider myself an athlete or a runner. I haven’t yet secured a bib. And, if I do, I will need to raise $7,500 for charity in order to get a spot.

And yet in some ways, this is a fairly comfortable “disruption” for me — I know how to raise money and just last weekend I ran 14.5 miles as part of my training. However, the investment of time needed to keep pursuing this dream might just thwart my conference-organizing goal. The “how” of launching a conference is far more challenging and outside of my established skill-set. The details are daunting, but with my vision of daring others to dream firmly before me, I am pressing forward, discovering my way one step at a time.

Once you know your greater purpose, there are lots of roads that will take you there. As Amar Bhide writes, 70% of all successful new businesses end up with a strategy different than the one they initially pursued. There are a gazillion methods and tactics, but there are very few whys. When we have a vision and believe in it, instead of seeing drudgery, we see discovery. Instead of aimless wandering, we see ourselves at the low-end of our personal growth curve. Once we know our why, there will be a how.

The Condensed January-February 2013 Magazine

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers