Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1490

December 26, 2013

The Right Network Can Make or Break Your Project

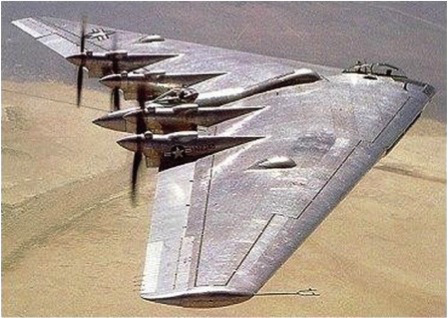

Does this airplane look familiar?

Source: Wikipedia

It should, because it’s a predecessor of the famous Stealth Bomber, a prototype completed by Jack Northrop’s company in 1948. In his time, Northrop — the inventor of the flying wing concept — was considered to be the aerospace genius, but he was not able to deliver on his promise to the U.S. military. The revolutionary airplane you never got beyond the prototype.

In 1980, Jack Northrop, then age 85 and confined to a wheelchair, visited a secure facility to see the first B-2 Stealth Bomber — the most advanced military aircraft capable of flying at extremely high altitudes and avoiding radar detection.

Source: Wikipedia

Even after 40 years of technological development and use of sophisticated computer design tools, the new bomber looked like a replica of Northrop’s original design for the flying wing. Reportedly, after seeing the aircraft, Northrop said he now realized why God had kept him alive for so long.

So why did one model fail and the other succeed? Part of the explanation can be found by comparing the different networks of alliances that Northrop’s company formed in the forties and in the seventies.

In 1941, his alliance network looked small and simple hub-and-spoke system. Otis Elevators worked on design, General Manufacturing and Convair provided production facilities. Notice that the partners don’t work with one another and the U.S. Army Corps was actually brought in to arbitrate a dispute between Northrop and Convair.

In 1980, the alliance network was more complex and highly integrated. Network partners worked with one another, jointly negotiating technical standards. Vought Aircraft designed and manufactured the intermediate sections of the wings, General Electric manufactured the engine, whereas Boeing handled fuel systems, weapons delivery and landing gear. In addition, each main partner formed individual ties with other subcontractors specific to their areas of responsibility.

As we discuss in our new book “Network Advantage”, networks like this have two main benefits. First, alliance partners are more likely to deliver on their promises. If information flows freely among interconnected partners, how one firm treats a partner can be easily seen by other partners to whom both firms are connected. So if one firm bilks a partner, other partners will see that and will not collaborate with the bilking firm again.

Second, integrated networks facilitate fine-grained information exchanges because multiple partners have relationships where they share a common knowledge base. This shared expertise allows them to dive deep into solving complex problems related to executing or implementing a project.

This is not to say that the hub-and-spoke network of the 1940s doesn’t have its uses. In fact, they are usually more effective at coming up with radical innovation than are complex, integrated networks. In a hub-and-spoke configuration it’s more likely that your partners will know stuff you don’t already know and combining new, distinct ideas from multiple spokes leads to breakthrough innovations for the hub firm.

But Northrop’s hub and spoke portfolio was not useful in 1940s, because he already had an innovative blueprint for the bomber. All Northrop needed to do was to build reliable manufacturing systems that would execute his ideas based on incremental improvements made by multiple partners at the same time. That scenario called for the integrated network of the 1970s.

The key to choosing between the two types of network is to ask: do you already have a final idea that needs to be implemented with incremental improvements? Is it important that all of your partners trust each other and share knowledge in implementing your idea? If so, then the integrated alliance portfolio is right for you. If you are exploring different options and it is not critical that your partners trust one another, work together to develop and/or implement them, then the hub and spoke portfolio is the best.

Can Groupon Save Its Business Model?

Not long ago, there was this multi-billion dollar company called Groupon that was going to revolutionize the business of bargains, whose founders turned down a $6 Billion offer from Google. Yet the revolution never came.

To turn its fortunes around after a long period of performing below (admittedly inflated) expectations, Groupon changed a core element of its business model sometime last year. The discounts available through Groupon coupons used to be subject to a host of restrictions, (e.g., “the deal is ON if at least 100 customers subscribe”), but now most Groupon coupons can be used any time, any day.

Will this change turn the company’s fortunes? Actually, it could turn out to be the nail in Groupon’s coffin. As we argue in a recent paper (and in this accompanying interview), behind Groupon’s spectacular rise and fall is a story of a business model that misaligned the incentives of Groupon and one of its key constituencies.

The sustainability of a business model depends on its ability to make all concerned parties better off. In the case of Groupon’s discounts, customers certainly get value by enjoying deep discounts and Groupon does well the more its discounts get used. A more interesting question is whether the merchants supplying the discounted goods and services also benefit: What do they get out of participating in a Groupon program?

Academic research has consistently found that running a deal using Groupon (or one of its competitors) has two main implications for a business: more customers in the short term but lower favorability ratings. Hence, short-term gains in traffic come at the expense of a lower future traffic and the overall value proposition to the merchant remains unclear.

Here is where restrictions come into the picture. Nearly all service businesses face seasonal demand (think of restaurants, theaters, museums) and are often unable to serve all customers in peak periods (e.g., weekends). Ideally, business owners want to restrict discounts to off-peak periods so that some demand shifts from peak to off-peak periods. And if demand in off-peak periods is too low, they will want to close down the business on these days.

With unrestricted discounts (as is now typical for Groupon) customers with discounts will come in droves during peak times, and the profit of the merchant may even decline since regular customers are substituted with coupon-bearing customers. Think about it: filling a restaurant’s capacity on Saturday evening with Groupon customers is probably not the savviest business decision.

But by having discounts limited to low-demand periods the merchant can be sure that no full-price paying customer is replaced, and by having an activation threshold, the merchant can be sure that the deal is active only when demand is high enough in an off-peak period to justify the business staying open. A win-win-win for all parties.

So why do most deals on Groupon and other similar web sites feature no time restrictions, and why are an increasing number of web portals removing activation thresholds? Because, unfortunately, what is in the interest of the business owner is not in the interests of Groupon and its competitors. Groupon and other web portals get a cut of total revenues channeled through the deal so Groupon gets nothing if the deal is not on. That is, with no activation threshold and with deals active always, Groupon itself gets the best deal… And the merchant gets a raw one.

But a business model that imposes this kind of misalignment is not sustainable. Unless Groupon restores the restrictions, the prospects for its long-term survival are dim, as the bigger, better-known merchants themselves can fairly easily offer structured discounts directly. Interestingly, there are signs that this might happen: time-restricted discounting has been reintroduced into Groupon Reserve.

This may seem like a backwards step. But the hard truth is that without restrictions, Groupon is definitely dead, if not today, then tomorrow or at some point in the not too distant future. Of course, it may not survive without restrictions either because perhaps this was just a revolution that was never meant to be.

Research: Most Large Companies Can’t Maintain Their Revenue Streams

My research finds strong evidence that the majority of large companies do not successfully maintain their current revenue streams, let alone grow them over time. My “growth outliers” project looked at publicly traded firms with market capitalizations of greater than US 1 Billion as of 2009, using data from Capital IQ. I found that in the period from 2000 to 2009, over half of the firms in the sample shrunk their revenue by 10% or more in at least one of those years, clear evidence of eroding competitive advantage.

In that same study, there is also striking evidence of the rise of global competition. In the 2004 sample, roughly 20% of the firms came from emerging markets. Just five years later, fully 38% of the sample was from emerging markets, with significant increases from companies based in South Korea, Israel, Brazil, Hong Kong and of course India and China. This trend has been underway for a while. As the Economist observed in a 2005 article,

Years ago, when products did not change much and companies largely stuck to their knitting, American and European consumers faithfully bought cameras from Kodak, televisions from RCA and radios from Bush, because those brands represented a guarantee of quality. Then the Japanese got better at what they made. Now the South Koreans are doing the same. And yet with many American and European electronics companies making their gadgets in the same places, even sometimes the same factories, as their Asian competitors, the geography of production has become less important.

Other researchers have found similar patterns. Richard Foster, an advisor to the consultancy Innosight, found that the lifespan of companies in the Standard and Poors 500 (an index chosen to represent the total economy) has been steadily shrinking for decades (Foster, 2012). In 1960, a typical S&P company had been around for 60+ years. By 2010, the typical S&P company was 16 or 17 years old. Further, the index is extremely dynamic. According to Foster’s research, a new firm is added and an existing one removed roughly every two weeks! Thus firms such as Express Scripts, Juniper Networks and Google enter the index while firms such as Sears, The New York Times and Radio Shack exit it.

Students Get Lower Grades in Online Courses

Although students who take online courses in community colleges tend to be better prepared and more motivated than their classmates, a study by Di Xu and Shanna Smith Jaggars of Columbia University shows that the online format has a significant negative impact on students’ persistence in sticking with courses and on their course grades. For the typical student, taking a course online rather than in person would decrease his or her likelihood of course persistence by 7 percentage points, and if the student continued to the end of the course, would lower his or her final grade by more than 0.3 points on a 4-point scale. Before expanding online courses, colleges need to improve students’ time-management and independent-learning skills, the researchers say.

If You Want to Change, Don’t Read This

There is a great scene in Godfather 2 where Kay (Diane Keaton) complains to husband Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) about his unfulfilled promise to make his business fully legit and quit being a mafioso. Michael responds that he is still working on it, reassuring Kay emphatically: “I’ll change, I’ll change — I’ve learned that I have the strength to change.”

Although most of us aren’t part of the mafia, we are still a bit like Michael Corleone in that we overestimate our capacity for change. In theory everyone can change, but in practice most people don’t… except for some well-documented changes that affect most of us.

For example, most people display antisocial tendencies during adolescence and slower thinking in late adulthood, but these changes are by no means indicative of a psychological metamorphosis. Rather, they are akin to common lifespan changes in physical traits, such as gains or drops in height during childhood and late adulthood, respectively — they occur to everyone. Likewise, there are typical changes in personality, even within 5-year periods. A seminal review showed that we become more prudent, emotionally stable, and assertive with age, while our energy and intellectual curiosity dwindle after adolescence. In other words, as we grow older we become more calm and mature, but also more passive and narrow-minded.

A more interesting question is whether categorical changes are feasible. Can someone be extremely introverted at certain age, but super outgoing at another? Can someone transition from being a self-centred narcissist to being a caring and giving soul? Or from being exceptionally smart to being incredibly stupid?

On the one hand, there is no shortage of famous case studies to illustrate radical transformations in people’s reputation (their public persona). Sometimes these changes — like Miley Cyrus’s transformation from innocent Disney star to tongue-wielding twerker — seem more like carefully planned PR campaigns than true psychological journeys. But others do make us wonder if there’s something deeper going on inside. Bill Gates started as a stereotypical computer nerd, then turned into a talented entrepreneur, then morphed into a ruthless empire-builder, and then became the most charitable person on earth, giving away most of his — and his friends’ — wealth. The late Nelson Mandela, perhaps the least disputed moral figure of our times, had an arrogant, aggressive, and antisocial youth before inspiring everyone with his path of nonviolent resistance.

And yet scientific studies indicate that categorical changes in character are unusual. When there is change, it usually represents an amplification of our character. In other words, even when our patterns of change are unique, they are predictable: we simply become a more exaggerated version of ourselves. This happens in three different ways. First, we tend to interpret events according to our own personal biases, which only reinforces those biases. For instance, pessimists perceive ambivalent feedback as criticism, which, in turn, enhances their pessimism over time; the opposite happens with optimists. Second, we gravitate towards environments that are congruent with our own default attitudes and values. Hedonists seek pleasure and fun-loving people, which, in turn, makes them even more hedonistic. Aggressive people crave conflict and combat, which only augments their aggression. Altruists hang out with caring people and spend time helping others, which enhances their empathy and reinforces their selflessness. Third, our reputation does truly precede us: others (including strangers and acquaintances) make unconscious inferences about our character in order to explain our behavior and predict what we may do next. These intuitive evaluations may be inaccurate, but they are still self-fulfilling. With time, we morph into the person others think we are; their prejudiced and fantasized representation of us turns real and becomes ingrained in our identity. Reputation really is fate.

As a consequence, deliberate attempts to change are far less effective than we like to think, which is why most New Year’s resolutions are never accomplished — and why our long-term happiness levels are fairly constant and relatively immune to extreme life events (whether it is a painful divorce or the joys of winning the lottery).

Needless to say, some people are more capable of changing than others. Ironically, those individuals tend to be more pessimistic about their very chances of changing. Indeed, neurotic, introverted and insecure people are more likely to change, whereas highly adjusted and resilient individuals are less changeable. Likewise, optimism breeds overconfidence and hinders change by perpetuating false hopes and unrealistic expectations.

So, how can we change? The recipe for self-change is fairly straightforward — it is just hard to implement. In order to change, we need to start by building self-awareness, which is best achieved by obtaining (and believing) honest and critical feedback from others. Next, we must come up with a realistic strategy that focuses on attainable goals, such as changing a few specific behaviors (e.g., more eye contact, less shouting, more smiling, etc.) rather than substantial aspects of our personality (e.g., interpersonal sensitivity, empathy, and sociability). Finally, we will need an enormous amount of effort and dedication in order to both attain and maintain any desired changes — or we will quickly revert to our old habits. In short, change requires self-critical insight, humble goals, and indefatigable persistence. It means going against our nature and demands extraordinary levels of willpower.

So think carefully before you promise to change. And if you have tried to change and failed — well, you’ve got lots of company.

December 25, 2013

Conflict Strategies for Nice People

Do you value friendly relations with your colleagues? Are you proud of being a nice person who would never pick a fight? Unfortunately, you might be just as responsible for group dysfunction as your more combative team members. That’s because it’s a problem when you shy away from open, healthy conflict about the issues. If you think you’re “taking one for the team” by not rocking the boat, you’re deluding yourself.

Teams need conflict to function effectively. Conflict allows the team to come to terms with difficult situations, to synthesize diverse perspectives, and to make sure solutions are well thought-out. Conflict is uncomfortable, but it is the source of true innovation and also a critical process in identifying and mitigating risks.

Still, I meet people every day who admit that they aren’t comfortable with conflict. They worry that disagreeing might hurt someone’s feelings or disrupt harmonious team dynamics. They fret that their perspective isn’t as valid as someone else’s, so they hold back.

Sure, pulling your punches might help you maintain your self-image as a nice person, but you do so at the cost of getting your alternative perspective on the table; at the cost of challenging faulty assumptions; and at the cost of highlighting hidden risks. That’s a high cost to pay for nice.

To overcome these problems, we need a new definition of nice. In this version of nice, you surface your differences of opinion, you discuss the uncomfortable issues, and you put things on the table where they can help your team move forward.

The secret of having healthy conflict and maintaining your self-image as a nice person is all in the mindset and the delivery.

To start shifting your mindset, think about your value to the team not in how often you agree, but in how often you add unique value. If all you’re doing is agreeing with your teammates, you’re redundant. So start by telling yourself “it’s my obligation to bring a different perspective than what others are bringing.” Grade yourself on how much value you bring on a topic.

Here are a few tips on improving your delivery:

1. Use “and,” not “but.” When you need to disagree with someone, express your contrary opinion as an “and.” It’s not necessary for someone else to be wrong for you to be right. When you are surprised to hear something a teammate has said, don’t try to trump it, just add your reality. “You think we need to leave room in the budget for a customer event and I’m concerned that we need that money for employee training. What are our options?” This will engage your teammates in problem solving, which is inherently collaborative instead of combative.

2. Use hypotheticals. When someone disagrees with you, don’t take them head on—being contradicted doesn’t feel very good. Instead, a useful tactic is to ask about hypothetical situations and to get them imagining. (Imagining is the opposite of defending, so it gets the brain out of a rut.) If you are meeting resistance to your ideas, try asking your teammates to imagine a different scenario. “I hear your concern about getting the right sales people to pull off this campaign. If we could get the right people…what could the campaign look like?

3. Ask about the impact. Directing open-ended questions at your teammate is also useful. If you are concerned about a proposed course of action, ask your teammates to think through the impact of implementing their plan. “Ok, we’re contemplating launching this product to only our U.S. customers. How is that going to land with our two big customers in Latin America?” This approach feels much less aggressive than saying “Our Latin American customers will be angry.” Anytime you can demonstrate that you’re open to ideas and curious about the right approach, it will open up the discussion (and you’ll preserve your reputation as a nice person).

4. Discuss the underlying issue. Many conflicts on a team spiral out of control because the parties involved aren’t on the same page. If you disagree with a proposed course of action, instead of complaining about the solution, start by trying to understand what’s behind the suggestion. If you understand the reasoning, you might be able to find another way to accomplish the same goal. “I’m surprised you suggested we release the sales figures to the whole team. What is your goal in doing that?” Often conflict arises when one person tries to solve a problem without giving sufficient thought to the options or the impact of those actions. If you agree that the problem they are trying to solve is important, you will have common ground from which to start sleuthing toward answers.

5. Ask for help. Another tactic for “nice conflict” is to be mildly self-deprecating and to own the misunderstanding. If something is really surprising to you (e.g., you can’t believe anyone would propose anything so crazy), say so. “I’m missing something here. Tell me how this will address our sales gap for Q1.” If the person’s idea really doesn’t hold water, a series of genuine, open questions that come from a position of helping you understand will likely provide other teammates with the chance to help steer the plan in a different direction.

Conflict — presenting a different point of view even when it is uncomfortable — is critical to team effectiveness. Diversity of thinking on a team is the source of innovation and growth. It is also the path to identifying and mitigating risks. If you find yourself shying away from conflict, use one of these techniques to make it a little easier.

The alternative is withholding your concerns, taking them up outside of the team, and slowly eroding trust and credibility. That’s not nice at all.

Leading by Letting Go

If you are running a large company anywhere in the world, you have almost certainly asked yourself some version of this question: “How can we get tens of thousands of employees to deliver memorable customer experiences that enhance our brand, all at a reasonable cost?”

The answer many have latched onto might best be called “Tightening the Grip.” This involves making it easier for employees to deliver in the same way every time by prescribing exactly what they should do in all circumstances. In a customer service center, for example, you would create scripts for every possible interaction. You’d ensure quality by listening to recordings and holding service representatives accountable for meeting detailed standards, such as using a customer’s name a certain number of times on each call. You would recognize high performers, and you would discipline reps who didn’t measure up. You would also monitor average call time closely for every representative. To keep costs under control, you’d set goals for reducing it every year.

Jim Bush had a different idea, which I have now come to call “Leading by Letting Go.” I’ve mentioned him before in my blog posts, but I haven’t really told the whole remarkable story.

Bush took over American Express’s far-flung service operations in 2005. He was suddenly responsible for many thousands of call-center employees. Even though American Express was well-known for its outstanding service, the company at the time regarded Bush’s organization purely as an expense, and it followed the conventional command-and-control model in its call centers. Leaders kept a tight rein on costs, with goals for reducing average call time, improving customer satisfaction levels, and driving more service volume to the Web. While customer satisfaction was at acceptable levels, competitors seemed to be catching up. Especially troubling to Bush, employee turnover was high, reflecting a long-standing decline in employee morale and imposing a huge burden on the organization.

Bush saw a way to change the game. Service at American Express, he argued, should not be treated as just a cost center; rather, it offered an opportunity to invest in building the sort of warm relationships between American Express and its customers that the venerable company’s brand had always been based on. Every interaction offered a chance to make people feel good about their relationship with the company. Every contact offered an opportunity to increase the likelihood that they would sing the company’s praises to friends. That kind of viral marketing would be invaluable in setting American Express apart from rivals and would power the company’s growth and profits.

The trouble was that the scripts, metrics, and rules were getting in the way. Heavily scripted representatives couldn’t form genuinely warm and empathic relationships. They sounded wooden and stilted. Real relationships are built on open, person-to-person communication, one caring human being to another.

So Bush decided to let go. He eliminated the scripts. He stopped focusing on call time and declared that from now on representatives would let customers set the pace, determining how much time they would spend on each call. He elevated the hiring process, seeking out people with the right personal qualities and values, often with experience in the retail or hospitality industries rather than in other call centers. (The centers’ high turnover helped him change things on this front pretty quickly.) He even changed the name of the job. He called the service reps customer care professionals and gave them business cards, along with higher pay and greater flexibility in scheduling their hours.

Then he created a system that enabled and encouraged these professionals to deliver outstanding service on their own, day in and day out. It depended upon four key elements:

A clear goal. American Express wanted warm, caring interactions with customers, unregulated by the clock or by scripts. The customer care professionals would see information about each caller on their screen, and they would get intensive training in the company’s products and policies. What they talked about was up to them — and to the customer. They would measure their success by the Net Promoter score — the percentage of customers who said, when asked, that they would recommend American Express to a friend.

Guardrails. People handling calls understood where they had latitude and where they didn’t. They knew they were accountable as teams for delivering the best possible service within the constraints of the company’s policies and in strict compliance with laws and regulations. Within those guardrails, however, they were free to exercise their judgment.

High-velocity feedback. The company began seeking feedback from a sample of customers after each transaction, asking them how likely they would be to recommend American Express to a friend and why. The resulting scores and verbatim comments flowed to frontline team leaders and customer care professionals every day, so they could see where they were succeeding, where they still had work to do, and what, specifically, the customers had pointed out.

Coaching and support. Supervisors and experienced customer care professionals were freed up from a number of other tasks so they could devote more time to coaching around the feedback. They helped new hires get up to speed. Trainers taught best practices and ways to improve. Teams shared with and learned from one another.

The results? Call-handling time edged up slightly at the very beginning, then dropped and kept falling. Likelihood-to-recommend scores doubled, indicating far more enthusiastic advocacy of American Express on the part of customers. Employee attrition was cut in half. Within just three years, the company saw a consistent 10% annual improvement in what Bush calls “service margins.” The company began to win the J.D. Power customer service award in credit cards year after year.

It is simply impossible for any leader to prescribe exactly what thousands of employees should do every day and in every circumstance. Even if it were possible, doing so would reduce their behavior to only what could be scripted and supervised. More importantly, the mere attempt to do so is dehumanizing and demoralizing. It drains the life and the initiative out of even the most highly motivated workers.

But when you set up a system that enables you to let go with confidence — to trust your employees to exercise their own judgment and learn from their experience — employees can become both self-directing and self-correcting. They become inspired, energetic, and enthusiastic. And the experience they deliver to customers is likely to be far better than anything you could ever control.

Get a Better Return on Your Business Intelligence

There is a lot of hype and buzz around business intelligence. Companies are investing millions of dollars in business intelligence technology. However, unless this is accompanied by the simultaneous creation of a strong foundation for taking intelligent business actions, they are unlikely to reap a good return on that investment.

An analogy might help explain what we mean by this. Imagine a plane heading from Dallas to New York. If that flight’s trajectory were just a degree off, it would end up in the ocean instead. The fact is that planes are more than a degree off 95% of the time, yet most planes land where they are supposed to. In spite of all the storms, the changing wind conditions, turbulence, and all the volatility and uncertainty they encounter along the way, they manage to land at their intended destination. Similarly, we believe the primary purpose of an investment in business intelligence should be to help companies reach their intended destinations in spite of all the storms they are likely to encounter along the way. So by learning how pilots are successful, leaders can get a much better return on their business intelligence initiatives.

How is the pilot successful? By managing six critical variables effectively. These variables are the essential ingredients for business success:

1. Starting Point. The pilot knows clearly that he is starting in Dallas. There is nothing clouding his understanding of the current reality as it is, not as he would like it to be, not as it appears to be, not as his copilot describes it to be. Similarly, there should be a good, data-centered understanding of the reality as it is — with holistic data across the functional silos, that is available in a timely manner, and which describes the current status of the business accurately.

2. Destination. The pilot can’t just land in a random location and declare, “You have arrived.” He must make proactive choices to reach a predetermined destination. Similarly, business intelligence must be viewed against the backdrop of a clear vision, goals, and strategy, and used as a means to getting there, rather than viewed in isolation or as a technology initiative. This vision should then be cascaded down so each decision maker has a clear idea of the destination they are working toward, while at the same time, ensuring that all these will add up to the same common goal.

3. The Plan. The pilot doesn’t take off until he has a clear flight plan, and he can understand how it will take him from the starting point to the destination. Similarly, business intelligence must be leveraged to create a plan that charts a path from where the organization is today to where it should be in the future. A visual way of depicting the plan — one that connects the starting point and the destination, and takes into account all the nuances of a business (more sales in fourth quarter, a spike in sales at month end and quarter end, etc.), seasonality, trends, etc. — will help with understanding the next variable, variation. In our experience, this element is weak in most business intelligence initiatives.

4. Variation. The pilot knows that he is going to be off 95% of the time. He expects variation from the plan and deals with it. Similarly, leaders need to anticipate variation. They should neither freeze in surprise when there is variation, nor should they create so much noise that the signal gets drowned out. Just like the pilot makes a calm assessment and operates the right levers, leaders need to create a climate and culture where people can make a calm assessment and fine-tune the right set of drivers. Without this one simple prerequisite, we have seen many business intelligence initiatives fail.

5. Act Early. When you are a degree off and you correct it early, it may be a matter of no more than a mile. Leave it for a while and it can compound quickly to hundreds of miles off course. The pilot has a cockpit full of tools that tell him where he is relative to where he should be and provide the visual cues he needs to act early and course correct often. Similarly, business intelligence must provide the visual and data-centered cues that show people the widening nature of the gap. For example, a bar chart by time period, one of the most common visual tools used, may not show the widening gap. However, a cumulative line graph can visually highlight the widening nature of the gap in a powerful way. Further, sales variation can get widened much more when it comes to financial variation because of fixed costs. It is not uncommon for a 5% drop in revenue to result in a 30% drop in profitability. Along the same lines, a 5% drop in revenue can result in a 50% drop in market cap. Such gaps must be exposed clearly and visually so employees understand the true impact of making decisions early.

6. Act Often. The pilot is making dynamic course corrections, perhaps every minute or so. He is not waiting an hour before deciding what to do. Contrast that with a typical business. A whole month goes by. A couple of weeks later the books are closed. Only then do leaders know where the business was last month. In addition, at best, this gives 12 opportunities for course correction over a typical annual cycle. If a plane were to attempt that Dallas–New York flight with just 12 course corrections, based on where the plane was at the time of the previous course correction, it will most certainly end up in the ocean. As volatility increases and uncertainty builds, the need for more frequent course correction accentuates. If there is only one thing a business intelligence initiative can focus on, we would say, put all that energy and focus on more dynamic, forward-looking course correction.

Unless a strong, intelligent, action-based foundation is in place to address each of these six critical variables, organizations are likely to get swept away by the buzz of business intelligence, become distracted by pretty charts on mobile devices, and end up landing where the winds take them. And when the external forces take charge, there is no guarantee it will be a safe landing. Instead, leaders must guide their companies safely toward their intended destinations.

Why Retail Clinics Failed to Transform Health Care

When retail clinics entered the U.S. health care market more than a decade ago, they were greeted with high expectations. The hope was their lower cost structure and focus on convenience and price transparency — two things sorely lacking in traditional health care — would engender radical changes. Retail clinics have demonstrated that they are a sustainable business model and clearly fit a patient need: Today, there are more than 1,600 clinics across the country, which have had a total of 20 million patient visits. Nonetheless, their performance has been disappointing: Their growth has been less than expected, they have not expanded care to underserved markets (namely, the poor), and their impact on health care spending — helping to lower it — remains unclear.

Understanding their disappointing performance is particularly important given that retail clinics are viewed as the prototypical example of how disruptive innovation can change the health care system for the better. The idea of disruptive innovation, a concept pioneered by the Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen and written about previously in HBR and in a book that one of us co-authored, is that industries are more commonly transformed by new entrants, rather than entrenched players. Disruptive companies get their start by offering affordability, convenience, and simplicity to previously neglected market segments that are too small and low margin for incumbents to pursue or aggressively defend.

Retail clinics fit this description to a tee. Because they employ nurse practitioners rather than physicians and offer care in locations such as pharmacies and grocery stores, retail clinics can provide services at a lower cost per encounter than traditional medical practices. In addition to lower cost, convenience has also been a key attraction, since patients are not required to make appointments and the clinics are often co-located with pharmacies. Most important, by focusing on a narrow set of simple medical conditions (10 conditions — including immunizations, strep throat, and ear infections — account for 90% of visits), retail clinics can deliver care that is equal in quality to that offered by incumbent providers.

Stalled Growth

Today, retail clinics nationwide receive roughly 6 million visits per year. However, the growth in the number of clinics has now plateaued, and they still account for less than 5% of the 100 million outpatient visits to physicians’ offices and emergency departments for simple acute conditions such as sinusitis and urinary tract infection, a number we might have expected to be higher by this point.

The disruptive-innovation model predicts that retail clinics would garner an initial following among “nonconsumers” — especially those without health insurance or who live in communities not adequately served by incumbent institutions. However, the convenience of retail clinics has been a selling point primarily in higher-income communities, where patients have health insurance and access to a physician. Although retail clinics are more affordable than physician practices, they have not been effective in attracting the largest population of nonconsumers: the poor, who paradoxically continue to rely on costlier sources of care such as emergency departments.

Reasons for the Limited Impact

The disappointing performance of retail clinics can be attributed to some perversities in regulations and reimbursement in the current health care system. First, the expectation based on the disruptive innovation model was that traditional providers would view the simple acute problems treated at retail clinics as low-margin services they would give up. However, due to a disconnect between reimbursement and actual costs of care, these incumbent providers view simple acute problems as high-margin work that offsets the losses from caring for more complex problems.

Second, these clinics are often staffed by nurse practitioners. But regulatory limitations on nursing scope of practice, which vary significantly from state to state, and regulation that fixes reimbursement to nurse practitioners at 85% of physician reimbursement for providing the same care, have impeded more rapid expansion of retail clinics.

Third, due to antiquated payment models, Medicaid plans that serve the poor have been reluctant to cover care in retail clinics and therefore shun the very market segment that may benefit the most from the convenience of retail clinics. Ultimately, as long as the U.S. health care system is driven by an administered payment schedule that bears little relation to the actual cost of care and allows some services to offset the costs of others, this system will always be prone to market irrationalities.

In summary, retail clinics exemplify both the potential of and challenges for disruptive innovators to improve value in health care. But clearly, the impact of such disruptive innovations will be limited unless the regulatory and reimbursement barriers are dismantled.

Shopping for Things Brings Emotional Benefits

Research participants who had viewed a movie clip of a sad scene (the death of a boy’s mentor in The Champ) registered a sadness decline of 2.28 points (on a 100-point scale) as a result of shopping for small quantities of office supplies such as ball-point pens, according to a study led by Scott Rick of the University of Michigan. The research underscores that making shopping choices helps to restore a sense of personal control over one’s environment and thus helps alleviate sadness, the researchers say.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers