Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1510

November 21, 2013

Reduce Stress with Mindfulness

Maria Gonzalez, author of Mindful Leadership, explains how to minimize stress – not just manage it. Contains a brief guided breathing exercise.

Bangladesh’s Garment Factories Still Aren’t Safe

In April 2013, over 1,100 workers died in Bangladesh when a garment factory complex called Rana Plaza collapsed. Are workers in that country or other emerging markets any safer today? That’s the discussion I moderated on November 18, 2013, at the Boston Global Forum.

There’s no dearth of candidates to share the blame for the accident. Building codes were inadequate, inspections were infrequent, and the enforcement of the law was lax.

Moreover, Rana Plaza is the tip of an iceberg. Bangladesh’s $20-billion garment industry has expanded rapidly in the last 10 years primarily because of low labor costs. With almost 5,000 factories in the country, over two dozen members of parliament among the owners, and with corruption rampant, weak enforcement of the law is inevitable.

Contrary to popular perception, Western governments and international organizations can exert little influence on the Bangladeshi government or companies. World Trade Organization members cannot discriminate against each other, so no country can legally subject garment exports from Bangladesh to quotas or additional tariffs to ensure that the state enacts or enforces laws. In addition, 20 million people, mainly women, earn their livelihoods by working in the garment industry in the country. Any ham-fisted corrective action would leave them unemployed.

The World Bank deflects all labor issues to the International Labor Organization (ILO), whose conventions focus primarily on the rights of labor to organize and to strike for better conditions. While the ILO has promoted workplace safety in recent times, its regular budget doesn’t support hiring on-the-ground inspectors even if the Bangladeshi government would allow them to inspect factories and monitor the enforcement of safety regulations.

That leaves two forces that can improve workplace conditions: Pressure by consumers of Made-in-Bangladesh garments and the responsibility that companies placing orders on Bangladeshi factories may feel because of the efforts of consumers and employees.

The problem is that the bulk of the country’s exports are low-price, low-quality items that are often sold unbranded or as private label products. The low-income consumers who buy these garments are price sensitive and most likely, unwilling to pay even a little extra to correct workplace conditions in a country they have never heard of. Consumer interest is easier to muster among high-income buyers of products such as premium coffees.

Many major retail brands, such as Europe’s H&M and Zara and the U.S.’s Wal-Mart and The Gap, source garments from Bangladeshi factories. To the surprise of many, these companies have stepped up to the challenge. Over 100 European companies have signed a legally binding accord that involves funding the inspection and upgrading of the 1,500 plus factories they use in Bangladesh. Over 25 American companies have signed a non-legally binding agreement that will do much the same for another 620 factories, and they will offer factory owners up to $100 million in low-interest loans.

In addition, a re-energized ILO, with financial support from the U.K. and Dutch governments, has pledged over $24 million to support inspections, training programs, and improvements at the roughly 2,500 high-risk factories that aren’t covered by the Accord or the Alliance.

Such collective action is essential. Bangladesh’s factory owners, who operate with tight margins in a highly competitive industry, find it tough to invest in improvements. Although those investments would attract people, retain workers, and improve long-term productivity, the short-term increase in costs would mean lost orders. Likewise, if Wal-Mart were to unilaterally impose its conditions in Bangladesh, its costs and retail prices would increase sharply.

However, if the major players that source the bulk of Bangladesh’s exports follow through and implement their agreements, conditions for workers could well improve. The fact that there are two groups complicates implementation, but friendly competition and coordination between them could lead to faster and more sustainable results.

Workplace safety isn’t the only issue confronting workers in Bangladesh. Despite support from nongovernmental organizations, organizing unions has proved difficult in the country. Thousands of garment workers went on strike in October 2013 to demand an increase in wages from $40 to $100 per month. Such a large increase might risk the loss of some jobs to Myanmar and other low cost countries, but the sheer scale of the Bangladeshi garment industry cannot be quickly replicated in another country.

Should the responsibility of Western retailers and manufacturers extend beyond workplace safety to the human rights of workers in the factories of their contractors and subcontractors? In a globally integrated economy, Western multinationals have the ability to exert more influence as a force for good than do any other stakeholders. The question therefore is not whether they should, but how quickly and effectively multinationals can work with factory owners, managers, and worker organizations in Bangladesh to implement improved safety and workplace conditions.

The Job Market for MBAs is About to Take a Hit

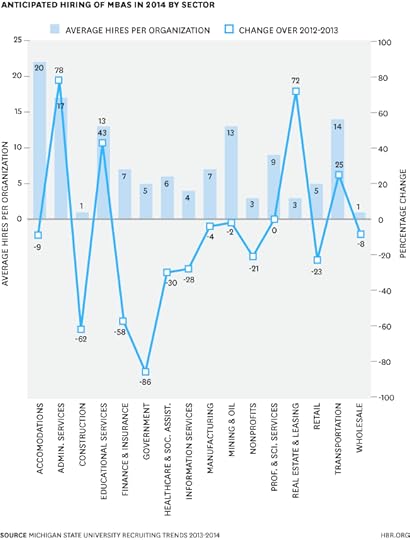

If you’re graduating from business school this spring, you might want to be sitting down for this: the job market for recent MBA graduates looks poised to get a lot worse in 2014. That’s based on an annual survey conducted by Michigan State University, released yesterday. Though not random, it samples nearly 6,100 employers who recruit across 300 U.S. colleges and universities, asking about their anticipated hiring in the coming year, as compared to their actual hiring this year. The news is positive for those about to graduate from college, but potentially distressing for soon-to-be MBAs.

First the good news: Hiring of college graduates is expected to increase three percent in 2014, with some sectors doing even better than that.

“Strong demand for accounting, marketing, computer science, engineering, human resources, public relations, and the inclusive ‘all majors’ group will increase hiring for Bachelor’s degrees by seven percent,” writes lead economist Phil Gardner. The overall number would be even higher, in double digits, except that the normally robust financial services sector seems to have lost its appetite for hiring. Which brings us to MBAs:

The market for new MBAs has been hit hard. Since January, finance institutions have been shedding jobs by the thousands and curtailing hiring targets for new graduates. The federal government also expects to hire far fewer MBAs this academic year. Professional and scientific services, mining and oil, and manufacturing do not expect to change their hiring levels. The total contraction in the market for new MBAs will approach 25 percent.

The decline in government hiring is attributed to sequestration, the shutdown, and debt limit “brinkmanship.” As for finance, the survey cites news reports which attribute the sector’s contraction to a variety of factors, including a slump in the mortgage refinancing industry.

The report notes that some employers, concerned over economic uncertainty, planned to replace MBA hires with Bachelor’s candidates to cut costs.

The news comes as the number of newly minted MBAs continues to increase, as noted by the report. While graduates of top programs will likely be fine, Gardner cautions that “MBAs with little professional experience may have more difficulty landing a job commensurate with their education.”

Still the Sexiest Profession Alive

In a week when People magazine announced its annual “Sexiest Man Alive,” I can’t help recalling an HBR article Tom Davenport and I published last year that was titled along similar lines. We called it “Data Scientist: The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century.”

The headline got some laughs, but no one seriously debated the point once they understood how we were defining “hot.” Data scientists are very much in demand as companies grapple with the challenge of making valuable discoveries from Big Data. They’re often exotic, coming from data-oriented scientific backgrounds rather than MBA programs. And they tend to be mavericks, moving between business and IT colleagues and challenging the perspectives of both.

But a year has now passed. Do they still, as a group, deserve the honor?

First, let’s be clear—data science is still sexy. There continues to be a huge appetite on the part of businesses to find the treasure in large, unstructured datasets, and a widespread understanding that not just anyone can do it. The qualities we outlined in the original article are still very much part of the profession. Great data scientists are not only adept at coding but have creative intelligence, and a knack for storytelling, both verbally and visually.

But, as when any profession is declared the next “hot job,” the composition of the group is changing fast. As the field grows and evolves, the first generation of highly trained, highly passionate young data scientists is being joined by others who hopped on the bandwagon as a simple career move, responding to market demand and hoping for steady employment. It’s turning into a mixed bag.

Of course it’s a good thing to see the growing availability of data science programs in academia. As recently as 2011, there were next to no formal training programs. Now, there are solid data science or advanced analytics programs in place at Columbia’s Institute for Data Sciences and Engineering; UC Berkeley’s iSchool; Carnegie Mellon University; Illinois Institute of Technology; Imperial College, London; North Carolina State; Syracuse University; and the University of Tennessee.

Meanwhile, companies like IBM are partnering with universities to close the Big Data skills gap. And there are pioneers from early data science groups at Yahoo! and LinkedIn now scattered throughout the tech world, dedicating themselves to training and inspiring the next generation of data scientists. The Insight Data Science Fellowship Program started by Jake Klamka is a prime example. Insight is an intensive six-week postdoctoral training fellowship bridging the gap between academia and a career in data science and data analytics. It takes 20 Ph.D.s, trains them, and places them into the top companies. Competition is fierce. For each class there have been over 200 applicants, and 100 percent of the fellows have been placed into organizations (the majority after receiving multiple offers).

All of these efforts are exciting. It’s fantastic that academia and big business are teaming up to offer coursework and training to budding data scientists. (Meanwhile, looking at the gap from the other side, I have also tried to address the shortage by drawing up specific descriptions of what hiring managers should look for in recruits as they build their data science teams.)

The question, though, is how to preserve the excitement of the field and continue to attract the best and brightest to its fascinating questions even as we bring more structure and standardized training to the profession.

What really matters, in my opinion, is that we don’t lose sight of a basic truth: that the most important qualities of a great data scientist aren’t capabilities that can be taught in a classroom. They are traits that are part of a person’s makeup, and may even be innate. Appropriately, as individuals decide to enter the field, and as businesses choose among candidates, they should look beyond the obvious data points.

It will pay to remember that no matter what the setting, the difference between sufficient and sexy isn’t competence as much as curiosity. And what makes someone hot isn’t professionalism. It’s passion.

The Metrics Sales Leaders Should Be Tracking

As an executive vice president for sales, I spent countless hours reviewing, examining, and analyzing the sales forecast for my company. I required the managers who reported to me to do the same. And that’s what they asked their reps to do, too. We weren’t alone. Conversations between sales leaders, sales managers, and sales staff frequently focus only on numbers: Did you make them? Will you fall short? How much do you think you can sell in the next quarter? The result is an inordinate amount of time spent on inspection and reporting of numbers that are, speaking frankly, out of the control of any sales leader.

In a recent study, the Sales Education Foundation and Vantage Point Performance identified 306 different metrics that sales leaders used in their efforts to manage their business. These metrics fell into three broad categories: sales activities (things like the number of accounts assigned per rep, the number of calls made per rep, and percentage of account plans completed), sales objectives (like the number of new customers acquired, the percentage share of customers’ wallet, and percentage of customers retained) and the subsequent business results (revenue growth, gross profit, customer satisfaction).

Even though managers were spending more than 80% of their time focused, as I had been, on the second two categories, the report found that sales management could affect only the first – the sales activities. The other two couldn’t be directly managed since they’re outcomes, not the process by which the outcomes are gained.

Which sales activities should sales leaders be managing? In their book, Cracking the Sales Management Code, Jason Jordan and Michelle Vazzana break down sales activities into four discrete categories: call management, opportunity management, account management, and territory management. Different organizations might need to focus on one or another of these more intently, depending on both the nature of what they sell and where their organizational weaknesses lay. So depending on the needs of your sales organization or team, here’s a way to map the various sales activity metrics to the challenge at hand:

Sales leaders who need to improve call management — that is, the quality of the interaction between individual salespeople and prospects or clients — should focus on such metrics as call plans completed, coaching calls conducted, or even the number of calls that are critiqued and reviewed. Coaching in the area of call management is particularly valuable when the seller need make only a small number of calls to greatly affect the outcome of a given deal. In selling professional services, for example, the ability to create value in one or two interactions with a senior executive often makes or breaks the deal.

Sales leaders who need to improve opportunity management – the ability of their salespeople to vet, pursue, and close a multistage sale — should focus on the number of opportunity plans (outlining the actions required to move through the stages of the sales cycle) completed or the percentage of early-stage opportunities qualified — that is, fully vetted to confirm you are really reaching the right customers, that these customers have the potential to generate a reasonable amount of business for the effort it will take to gain it, and that they are in fact willing to budget sufficient sums to purchase your offering. Identifying bad deals in this way and getting them out of the way early may be the simplest way to increase your odds of success. Most companies I have worked with don’t want their sales teams pursuing every opportunity possible. Instead, they want to put their maximum effort on the opportunities that match some kind of ideal client profile.

Sales leaders who need to improve account management – the ability to enhance the long-term value of a single client – should focus on working with reps to develop and adjust account plans so that they define an overall strategy for the customer. This is also when it would be fruitful for you to spend time creating and monitoring standards for important client-facing activities like establishing peer meetings between your organization and the customer (by, for instance, arranging meetings between your CEO and the client’s CEO) or getting the customer to sit on your organization’s advisory council to provide feedback to your business. I have a high-tech client that tracks the amount of time executives spend each month with a single account that generates $65 million a year. Account management metrics are vital when a substantial portion of your organization’s revenue is concentrated in small number of key customers.

Sales leaders that need to concentrate on territory management – on how you allocate sales reps’ time among all the customers in a given territory — should focus on metrics like the number of customers per rep, number of sales calls made, and even sales calls to different types of customers. By managing the process of selecting, prioritizing, and meeting with target customers you can maximize the use of your sellers’ most precious resource — time.

Many sales leaders have been inadvertently micromanaging through revenue or profit numbers, which is counterproductive. This is your chance to provide your sales team with a new context to succeed in. By closely managing the things you can control, you will give your organization the best chance for success.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

You’ve Got the Information, But What Does It Mean? Welcome to “From Data to Action”

To Avoid the Customer Recency Trap, Listen to the Data

Are You Ready for a Chief Data Officer?

Does Your Company Actually Need Data Visualization?

November 20, 2013

Hierarchy Is Overrated

Maybe you’ve heard the old cliché – if you’ve got “too many chiefs,” your initiative will fail. Every time I hear it, I wonder, “Why can’t everyone be a chief?”

For instance, the Second Chance Programme is a group that raises money to help reduce homelessness among women here in Southeast Queensland. It’s achieved impressive results since being founded in 2001, and is run by a committee of about ten people. In the early days, a management consultant used the familiar chiefs/Indians line to predict they’d fail.

This kind of thinking assumes:

You need a hierarchy to succeed.

The people that do the work are of lower status than those that decide what work to do.

Organizations that don’t follow the norms are likely to fail.

I think that all of these ideas are wrong. Second Chance has certainly been very successful with their flat, non-hierarchical structure. They have achieved a great deal, while keeping their overhead close to $0. If the structure of the management committee was a problem, they would have failed by now.

But maybe this kind of structure only works for not-for-profits?

Nope. About 20% of the world’s websites are now on the WordPress platform – making it one of the most important internet companies. And yet, Automattic, the firm behind WordPress, only employs a couple hundred people, who all work remotely, with a highly autonomous flat management structure. GitHub is another highly successful firm with a similar structure.

So, maybe this structure only works for not-for-profits and software firms with open source platforms?

Well, Valve is a gaming company that makes Half Life, Portal and many other popular games. Their software is proprietary. And they are famous for not having bosses at all. And 37Signals has a structure that looks a lot like Automattic’s, while building software that enables distributed collaboration, such as Basecamp and Ruby on Rails.

Ok, then, flat structures work for not-for-profits and software startups. But you surely can’t run, say, a big manufacturing firm like this, can you?

Actually, you can. Take a look at W.L. Gore. Gore is one of the most successful firms in the world. They have more than 10,000 employees, with basically three levels in their organizational hierarchy. There is the CEO (elected democratically), a handful of functional heads, and everyone else. All decision-making is done through self-managing teams of 8-12 people: hiring, pay, which projects to work on, everything. Rather than relying on a command-and-control structure, current CEO Terri Reilly says:

“It’s far better to rely upon a broad base of individuals and leaders who share a common set of values and feel personal ownership for the overall success of the organization. These responsible and empowered individuals will serve as much better watchdogs than any single, dominant leader or bureaucratic structure.”

They’ve had challenges in maintaining their structure as they’ve grown, but the remain one of the most innovative and most profitable firms in the world.

But all of these examples have had flat structures from the day they were founded – you couldn’t do something like this in a firm that has been operating for a while with the normal hierarchical structure, could you?

That’s exactly what Ricardo Semler and his team at Semco did when he joined the firm in 1983. In the 30 years since, the Brazilian conglomerate has continually worked at distributing decision-making authority out to everyone. One of the firm’s key performance indicators is how long Semler can go between making decisions. The time keeps getting longer, while the firm has maintained around 20% growth for nearly 30 years now.

All of these are examples where everyone is a chief. The flat organizational structure can work anywhere. This works best when:

The environment is changing rapidly. Firms organized around small, autonomous teams are much more nimble than large hierarchies. This makes it easier to respond to change.

Your main point of differentiation is innovation. Firms organized with a flat structure tend to be much more innovative – if this is important strategically, then you should be flat.

The organization has a shared purpose. This is what has carried Second Chance through their tough times – their shared commitment to the women they are helping. While the objectives may differ, all of the firms discussed here have a strong central purpose as well.

There is a growing body of evidence that shows that organizations with flat structures outperform those with more traditional hierarchies in most situations (see the work of Gary Hamel for a good summary of these results). But while we are seeing an increasing number of firms using flat structures, they are still relatively rare. Why is this so?

It’s not because people haven’t heard of the idea. There have been more than 200 case studies of Gore and Semco alone, and I would bet that nearly every MBA program in the world includes at least one case study looking at a firm with this kind of structure. But there are other obstacles:

Many people don’t believe in democracy in the workplace. Even people who adamantly oppose small amounts of central planning in government are perfectly happy to have the strategy of even very large firms set by just a handful of people.

Even if you do believe in democracy, it can be hard to imagine work without hierarchy. The “normal” structure is so deeply ingrained, and so widespread, that it can challenging to even think of an alternative in the first place. That’s why these case studies are so important.

Fear of the unusual. John Maynard Keynes said, “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” Unfortunately, this is still largely true today.

It’s hard to change organizational structures. Despite the positive example of Semco, in reality it is very hard to change organizational structures. Even with Semco, it took a financial crisis to trigger the change in thinking. It takes a strong belief in democracy in the workplace along with a resistance to criticism to stay the course and execute such a change.

However, as digital technologies make it easier to work in a distributed manner, and we enter the social era, flat structures will become increasingly common. There are sound business reasons for treating people with dignity, for providing autonomy, and for organizing among small teams rather than large hierarchies.

It’s time to start reimagining management. Making everyone a chief is a good place to start.

How Korea Can Avoid Japan’s Economic Mistakes

Around 20 years ago, Japan’s middle-income class started to collapse. Up until the 1980s, Japan had boasted of its “100-million population, all middle-class society.” Afterwards, it was forced to admit that this had degenerated into a “society of disparity.” While 80% to 90% of the Japanese population considered themselves middle class in the 1980s, according to a Seoul University study, this plunged to less than 30% by 2007. The underlying causes of this collapse offer lessons for South Korea, which is now undergoing a transition similar to Japan’s at the start of the 1990s.

There were three major reasons for the profound change in Japan’s economic and social makeup:

During the “lost two decades” starting in 1990, Japan’s economy either shrank, or inched up by just 1% or 2%. Sluggish domestic demand, an aging demographic and a strong yen, and the undermining of the competitiveness of Japan’s exports, all took their toll on growth rates.

Political uncertainties and the absence of strong leadership contributed to social fragmentation. There have been as many as 16 prime ministers in Japan since 1990, while the average term of each prime minister has been just around one year. This instability meant that Japan was unable to iron out a national consensus on its reform plan, or implement reforms in the long run.

The persistent low growth meant many domestic companies struggled or went bankrupt. Massive layoffs ensued, and the labor market turned flexible far too rapidly, with many formerly middle-class workers losing permanent contracts and reliable salaries. Despite high unemployment rates and increasing numbers of irregular workers, the Japanese government failed to overhaul the country’s welfare system so that it would be better able to prevent the dismantlement of the middle class. The Japanese welfare system was poorly suited to the task because it was led largely by corporations. The government’s welfare spending was too small to dole out benefits to those who lost jobs during business restructurings. Even though the Japanese government dared to take deficit financing in order to boost the economy, it mostly injected money into building infrastructure, but didn’t expand spending on welfare much.

In this regard, it is reasonable to worry about the future of Korea, because much of what occurred during Japan’s lost 20 years is currently happening there.

Korea has just entered a low growth stage. The Korean economy is increasing at a rate of less than 3% for the third consecutive year in 2013 – far below its potential growth. The aging demographic is making its economy lose steam, while sluggish domestic demand has continued for over 10 years, since the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Korea differs from Japan, however, in that its exports have been buttressing its growth. But the outlook for the country’s exports isn’t bright due to the strong won, and the slower than expected recovery of the global economy.

Korea is also following Japan’s footsteps in increasing the use of irregular workers, while its lack of a welfare system is stoking social unease and eroding economic vitality.

Both countries’ uncertainties in political leadership are also alike. Conflicts between the ruling and opposition parties are intensifying. The conservatives and liberals are becoming extremely polarized. The president’s leadership is weakening, too. Society hasn’t reached consensus on reform. And even if consensus had been reached, it would be impossible to make consistent efforts to pursue reform due to the current situation of the country.

Given these similarities, how can Korea avoid repeating Japan’s economic mistakes and failures?

Reinstating political leadership is the most crucial factor. Social consensus can only be forged when there is a strong leadership that can broker a grand compromise between the ruling and opposition parties, conservatives and liberals, and employers and laborers. That leadership, at the same time, should be capable of sustaining the consensus and making consistent efforts to do so.

Second, Korea must find a way to pull out of its current low growth trend. Its most urgent task is to invigorate investment. The government needs to encourage businesses by easing regulations, restoring entrepreneurship, and pacifying anti-business sentiment.

Third, Japan’s case should remind Korea of the fact that the rapidly aging Korean society is a critical cause of its lackluster economic growth. The country should come up with long-term and multifaceted measures to raise its birth rate, which is currently the world’s lowest. In addition, Korea needs to revise its immigration policies.

Fourth, while Japan mainly invested in its social infrastructure to boost its economy, Korea needs to focus on its highly educated human capital.

Finally, it is right to increase welfare spending, but the focus should be on a productive welfare system centered on active labor market policies such as supporting training programs for those who change jobs.

If these measures are taken, Korea will still be able to avoid the specter of two lost decades.

Get the Strategy You Need — Now

Two uncomfortable strategic truths face the vast majority of executives and companies – and probably you, too. First, you don’t have a powerful strategy. And second, you aren’t doing much about it.

Though both statements may sound extreme, they are the clear implication of new McKinsey research on how companies create value and allocate resources.

The widespread absence of a powerful strategy is clear from our recent study of 3,000 of the world’s largest companies, which finds that just 20 percent in that group create 90 percent of its total economic profit. The rest of the companies, more than 2,400, simply do not have a strategy that effectively outperforms the market.

A second new McKinsey study delves into the question of what executives are doing about their strategic shortfall, and concludes that most are not doing enough.

While they should increase investment in the parts of their business with the best shot at creating value and cut investment in business lines that are tapped out, they don’t. Instead they divvy up their corporate resources in the same way year after year, giving businesses, whether great or weak, essentially the same slice of corporate resources they had the year before.

Of 1,500 multi-business companies examined each year over the course of two decades, only a minority actively shifted a substantial share of their resources to their most high potential growth businesses. Even between 2007 and 10, when tough external conditions should have forced hard internal choices, leaders remained stuck in their tracks. A great opportunity for change was wasted.

Inertia is expensive. The corporate minority that actively reallocate their resources do much better financially than those that don’t. These “dynamic reallocators” produced a median total return to their shareholders of 10 percent per year between 1990 and 2010. That is far ahead of the 6 percent return earned by the companies which rarely reallocate – the “dormant reallocators.” And while resource dynamism made a big difference, the bar we set for it was not extraordinarily high: Companies moving just 41 percent of their capital base between businesses or to new business areas over a 15 year period made the cut.

Warren Buffett once said, “I was wired from birth to allocate capital.” Lucky for him! What should the vast majority of executives who aren’t genetically endowed like Warren do to boost their odds of identifying good strategic bets, and then putting their money where their strategy is?

1. Retool your strategy development process. Good analysis in the hands of smart managers does not automatically yield great strategy. The process of developing that strategy is critical. Unfortunately, nearly eight in ten executives surveyed by McKinsey describe the strategic-planning processes at their companies as more geared to confirming existing hypothesis than to testing new ones.

There are techniques to fix that problem. Among them: foster debate, create ‘challenger roles’ to institutionalize give and take and cut through the politics, and seek external perspective, even if it’s as simple as using outside analysts’ market predictions or making customer visits. Create a corporate-resource map that is granular enough to show specifically where resources are currently deployed. This data will enrich discussion and help make the case for reallocation even to powerful division leaders who don’t benefit from it themselves.

2. Test your new strategy. Strategy is not a procedural exercise, but a way of thinking. To stimulate strategic thinking, answer this question honestly: When you look objectively at your assets, capability and market position is there any reason to believe you can create disproportionate value?

One way to look at competitive advantage is to define it as an imperfection in the market, something which stops competitive forces from sucking away profit. Such advantages are scarce and often fleeting. Does your strategy tap a true source of advantage? Put you ahead of trends? Does it rest on unique and proprietary insights?

How confident are you that you can ‘beat the market’?

3. Execute decisively. Speed may be scary but one thing leaders need not worry about is reallocating too much. McKinsey research finds no evidence that the rewards of greater reallocation taper off. Managers appear to be most at risk of doing too little, not too much.

How much reallocation is needed varies, of course. Some successful reallocators enter and exit businesses entirely. But many more make less dramatic changes, shifting resources, year after year, to build up the best part of their business, and simultaneously pruning their less successful lines.

Whatever the degree of change required at your company, make it. Companies run by decisive CEOs rack up more economic profit — what’s left of operating profit after the cost of capital is subtracted – than competitors do. Returns to shareholders of reallocating firms are strong. It’s not just business, it’s personal: the CEOs willing to make the tough tradeoffs also have longer tenures in their jobs than those who are slow to shift assets. A better company, richer shareholders, and more job security are the rewards for being bold enough to build a powerful strategy and translate it into a real reallocation of resources.

Retool. Test. Execute. These are the priorities for leaders concerned that their strategy is undifferentiated or isn’t backed and implemented with sufficient resources. While change is never comfortable, our research suggests the bigger risk for many companies is not facing up to their strategy problem—or doing nothing about it.

Social Capital Is as Important as Financial Capital in Health Care

For a discipline so fundamentally altruistic, health care is oddly dysfunctional around relationships. That’s changing fast, of course, as providers are finding that cooperation is as critical to caregiving as cutting edge tests and therapeutics. But effective cooperation, particularly in a setting as complex as health care, requires more than a resolve to play well together; it requires leadership to explicitly recognize the need to build social capital across the organization, and implement a strategy accomplish it.

Yet building social capital — the trust and reciprocity among individuals and between groups — is rarely a specific focus of organizational leaders, though we believe it is as essential as financial resources for health care delivery systems. More than a decade of research on social capital in healthcare has found that higher levels are associated with improved coordination, increased job satisfaction and greater commitment among the staff, faster dissemination of evidence-based medicine — and better patients outcomes. As high performance on these measures is as important to organizational health as having a solid bottom line, leadership needs to invest in social capital and cultivate its growth with the same focus and discipline that it has applied to financial capital in the past.

Our full article describing social capital, its roles in health care, and strategies for building it in health care organizations is available here (PDF). The paper draws on the broad social capital literature and the toolkit for building social capital developed by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. The strategy at its core depends on nurturing five features of high-social-capital organizations: trust, reciprocity, shared values, shared norms, and openness. Among the tactics leaders can use to encourage these are communicating honestly (which should go without saying, but doesn’t always), building opportunities for interaction, establishing formal statements of responsibility and reciprocity, creating incentives for working together, establishing shared processes, engaging the staff in developing a statement of shared values, and using powerful stories about successes — and failures — in patient care to motivate staff and reaffirm organizational values.

To give just one example of storytelling, consider how the Cleveland Clinic made its decision to ask every patient seeking an appointment whether they would like to be seen today. That policy did not come from the marketing department, even though it is prominently advertised today. It came from one patient who sought an appointment, was given one in two weeks, and ended up in the emergency department that night. The patient didn’t die, and wasn’t harmed in terms of any of the classical “outcome measures.” But the leadership of the Cleveland Clinic had enough of a sense of “we” that they could decide “we find this intolerable,” and they began asking every patient if they wanted to be seen that day. You can only make this kind of decision if you have social capital in the bank.

Ultimately, the key to success is authenticity. Though social-capital building can be nurtured, it can’t be mandated. As Don Cohen and Laurence Prusak, former director of the IBM Institute for Knowledge Management, wrote in their book In Good Company: How Social Capital Makes Organizations Work, “Social capital thrives on authenticity and withers in the presence of phoniness or manipulation…[Leaders’] interventions must be based on a careful understanding of the social realities of their organizations and (even more difficult) a willingness to let things develop, even if the direction they take is not precisely the one envisioned.”

Our more detailed paper provides a framework organizations can use to begin building their social capital.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

When M&A Is Not the Best Option for Hospitals

The Big Barrier to High-Value Health Care: Destructive Self-Interest

A Framework for Reducing Suffering in Health Care

Fix the Handful of U.S. Hospitals Responsible for Out–of–Control Costs

To Avoid the Customer Recency Trap, Listen to the Data

A lot of stories emerge from customer data. The trick is figuring out which story to listen to.

Companies that are planning marketing campaigns typically look at their data on past responses to figure out which customers are most likely to react favorably, and they spend their marketing dollars accordingly. That makes perfect sense — it’s obviously more profitable to send an expensive catalog, for instance, to just those people who are the likeliest responders.

But this type of thinking can lead you into the recency trap.

It’s well known that a customer’s likelihood of buying declines as time passes since her last purchase. The effect can be dramatic, as you can see from the exhibit, which is based on data from a meal-preparation service provider in a study I conducted with Gail Ayala Taylor of Dartmouth, Kimberly D. Grantham of the University of Georgia, and Kimberly R. McNeil of North Carolina A&T State University.

Because a customer who hasn’t bought in six months, say, is an unlikely prospect, you don’t target her; receiving no communication from you, she continues to stay away. As this process continues, eventually the customer’s chance of buying falls virtually to zero — the customer is lost to the company. You’ve slid down the curve into the recency trap.

However, even if the customer hasn’t purchased in a long time, it could be worth investing in her. By sending her that expensive catalog, you may prompt her to buy something now. She then moves to the left along the curve and is more likely to buy again.

So which story is the right one—the one that tells you not to waste your money on a lapsed customer, or the somewhat counterintuitive one that tells you to invest in her?

In the case of the company we studied, it was clear that the extra marketing expense would be beneficial. Our mathematical model, which is based on a well-accepted understanding of the effect of recency of purchase on likelihood to buy, demonstrated that the company could increase customer value by hundreds of dollars per customer. The value of customers who otherwise would have been lost to the company could increase from nearly zero to roughly $150 per person, on average.

Reasonable people can reasonably disagree on which data story is the one that matters most. I can’t guarantee that our recency-trap-avoidance strategy works every time, particularly for companies in turbulent markets. In fact, one might argue that the recency curve is really a satisfaction curve. Customers will continue buying at regular intervals if they’re satisfied with your product. So if a lot of time has passed since their last purchase, that may mean they’re dissatisfied — they don’t like you anymore — and there’s little you can do to bring them back.

But sometimes customers stop buying even if they still like your products. They get out of the habit. They get distracted. They forget. But if you treat them as lost, they’ll become lost.

It’s all too easy to reject ideas that sound counterintuitive. However, you can take a counterintuitive idea and put it to the test. Companies that excel at database marketing are compulsive testers. They know that testing isn’t very expensive, and it can yield valuable results. They accumulate data of all kinds, and they become adept at listening to the surprising stories that sometimes emerge.

Your company should do the same: First, tap your company’s data to create your own version of the recency curve, plotting purchases against time since last purchase. Then establish a control group and a test group consisting of customers drawn from the middle of the curve who ordinarily would be ignored. See what happens if you market to the test group, but make sure you evaluate the test on a long-term basis, at least long enough for the customer to buy not only in this period but in subsequent periods as well. A successful test provides you with a road map for how to avoid the recency trap.

From Data to Action An HBR Insight Center

You’ve Got the Information, But What Does It Mean? Welcome to “From Data to Action”

Are You Ready for a Chief Data Officer?

Does Your Company Actually Need Data Visualization?

Nate Silver on Finding a Mentor, Teaching Yourself Statistics, and Not Settling in Your Career

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers