Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1460

March 3, 2014

Reduce Stress by Pursuing Four-Way Wins

The pendulum is finally swinging back from the apogee of complete immersion in work as the business ideal. A great hue and cry now strains to contain our out-of-control culture of overwork. We know it reduces productivity, destroys civic engagement, and produces all manner of stress-related health problems.

The good news is that you can do something about it, for yourself and for your employees. You can be less stressed and more productive by spending less time on and less attention to work — while being more engaged with your family, your community, and the things you do for just you. You can take conscious, deliberate action to pursue four-ways wins: practical steps toward making things demonstrably better in all parts of your life — at work, at home, in your community, and in your private life.

For decades, I’ve been refining what is now a proven method for producing four-way wins that works because it’s customized for each person who takes up the challenge. But there is still a heaping helping of skepticism that greets me wherever in the world I go to talk about it. I can tell you that, while it’s not easy, it is possible, for I’ve seen success in just about every kind of setting, from retail to manufacturing to human services, and everything in between. If you’re like most harried business professionals, it’s more possible than you now think it might be. Ready to give it a try?

Diagnose. Start by taking a minute to explore your personal four-way view — what’s important to you, where you focus your attention (your most precious asset as a leader), and how things are going in each of the four domains of your life. (You can use this free assessment tool and guide for help in doing so.) Then begin generating ideas for experiments you can try to better align what matters to you with what you actually do. It’s likely that this will mean attending to a non-work aspect of your life you’ve been neglecting.

This might be initiating an exercise program for yourself, carving out protected evening time for your family, or devoting attention to a project for your community, to name a few simple examples. Most importantly, there must be a real benefit, even if indirect, for your work and career, too. An essential aspect of this approach is realizing that an experiment in one part of life affects the others. For instance, you might choose to diet to lose weight (for your own better health); then this has ripple effects in your home and community domains because you’re less grumpy and have more energy for your family and friends. And you increase your performance at work as a result of greater focus and stamina. Similarly, an experiment conducted with the aim of creating greater satisfaction with your family by turning off your smartphone in the evening has beneficial business impact; in taking a hiatus from work in the evening, you return refreshed and are more productive.

Dialogue. Talk to a few of the most important people in the different parts of your life about what you really need from each other. These conversations serve to build trust and strengthen your future together, while you refine and expand your initial ideas about experiments to make things better in all four parts of your life.

Discover. Design an experiment in which you are deliberately aiming to improve your performance and results in each of the four domains — not to trade them off or to balance one against the other, but to enhance all of them. If you’re stuck, think a bit harder: I have coached and taught thousands of people to do this, and I’ve never met anyone who couldn’t come up with one such experiment about which they were very excited.

Get Help. Share your idea with someone, not only to get their advice, but also to build in accountability pressure. Ask them to help you stay on track with your experiment by checking in with you for five minutes each week for the next month. Ideally this would be a person who believes they are going to benefit from this new action you’re going to take. Why, for instance, would your boss benefit from your exercising more?

Get Moving. When you take intentional action to do what matters for people who matter, then your stress goes down. You feel a greater sense of control, and you learn that you have more freedom than you thought you had. You see that you can exercise choice.

To overcome the guilt that often accompanies the desire for change, it’s crucial that your experiments are not selfish. They’re not about you — they’re about you and your most important stakeholders. You are producing benefits for others at home, at work, and in your community. So, if one of your experiments is to arrive at work a half-hour later or leave earlier to go to the gym, spend time with your children, or serve on a community project, and this experiment does not result in improved performance at work, then you adjust it so that it does produce some benefit for your work, too.

In decades of experience, I’ve seen all kinds of experiments not only sustain themselves but grow contagiously precisely because others are invested in what you’re doing and they want to see you succeed. There’s something in it for them. And, inspired by your example, they then initiate their own experiments designed to create four-way wins.

The worst that can happen is that you don’t achieve the result you’d hoped for. But, if you reflect on what did or did not work with your experiment in the laboratory of your life, you will gain what is even more valuable than the immediate result, that is, useful insight on what it takes to produce change that is truly sustainable — change that lasts because it’s good not just for you, but for your world.

This is the fourth post in a blog series on taking control of stress. Stew Friedman is a contributor to the HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work.

Read the other posts here:

Post #1: How Couples Can Cope with Professional Stress

Post #2: When a Vacation Reduces Stress — And When It Doesn’t

Post #3: The Best Way to Defuse Your Stress

February 28, 2014

In an Age of Self-Promotion, Celebrating the Invisibles

Among the films nominated for an Oscar this Sunday, I am rooting for one in particular. Morgan Neville’s“Twenty Feet From Stardom”, a contender in the Best Documentary Feature category, is an examination of pop music’s backup singers, and launches its subjects, at least briefly, into the limelight. These artists have made crucial contributions to the oeuvres of some of the biggest names in music – The Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Bruce Springsteen, Luther Vandross – but to most fans are completely anonymous.

While the press has made much hay, and rightfully so, about these talented singers finally getting their due, what hasn’t been emphasized is the film’s message about the nobility in doing unseen work.

I’ve spent the past two years interviewing and meeting with “invisible” professionals like this film’s stars. I sought out people who are highly skilled, whose work is critical to whatever endeavor they are a part of, yet who are rarely, if ever, thought of by the public. These aren’t downtrodden laborers sweeping factory floors; every one of the people I profiled has ascended to the elite echelon of his or her field. I wanted to know: In a culture where attention, even fame, is a prevailing goal for so many, what kind of person takes pride in being so integral to an enterprise, yet is satisfied – and often prefers – to stay out of the spotlight?

What I discovered is that Invisibles share a core of common traits. The primary one is a deep ambivalence toward recognition. Among other traits, they also are meticulous about their craft, and relish their behind-the-scenes responsibility. In my forthcoming book Invisibles: The Power of Anonymous Work in an Age of Relentless Self-Promotion I explore how these traits, especially the first one, represent essentially the opposite mindset of our attention-seeking ethos today. Yet, intriguingly, despite an environment where career advisors insist on the power of “branding” oneself in order to get ahead, compelling research from a variety of fields shows that their unique attributes have a strong correlation with business success and personal fulfillment.

* * *

Close your eyes and sing to yourself the blistering climax to the Rolling Stones classic “Gimme Shelter” –

Rape, murder!

It’s just a shot away!

The paint-peeling background vocal, the very essence of the track, was originally sung by a woman named Merry Clayton. We don’t often think of legendary rock ‘n’ roll songs as products of the workaday world. But just like the most successful outputs of companies and brands, they take work – and not only by lone geniuses, but by small armies of consummate, and mostly unseen, professionals. In Merry Clayton’s case, she received a late-night call, literally at the eleventh hour, from someone connected to the band. Pregnant, and already in bed, Clayton got dressed, and sped to the studio. She sang the part just a couple of times, nailed it, and went back home.

Another singer featured in “Twenty Feet From Stardom” is Darlene Love, who, in addition to backing Elvis Presley, and regularly working for producer Phil Spector, even has had some center stage success of her own. Neither Clayton nor Love lack ambition. But listen to their advice to one of the film’s younger subjects, Judith Hill, who has begun to make a name for herself. In a video interview with theLos Angeles Times, the two express views on work ethic and fame that are, appropriately, in harmony. “Don’t stop singing background. It’s not gonna hurt you,” Love warns. “[Judith] said she turned down a lot of background sessions. You don’t turn it down. Because, where are they gonna see you?” Love knows she garnered the opening slot for several artists on huge tours only because they’d heard her sing background for them and knew how good she was. The power of the Invisibles’ approach is that, even if the ultimate goal is visibility, the way to reach it is through a commitment to invisible work.

Love adds that it’s also foolish to walk away from a paycheck. “It’s good money,” she said. “And don’t care what people say about you. They used to say to me all the time ‘Oh, you back Dionne Warwick?’ I said, ‘she pays me five thousand dollars a week. So yes, I ooh and ahh for Ms. Warwick and I enjoy it.’”

When Clayton was asked in another interview if it was a letdown that she never made it as a solo artist she answered, “I was disappointed when that album didn’t take off, sure, but then I turn around and [go] to London to do Tommy.” Because she focused on her singing, not exclusively on pursuing fame, there was always “something wonderful for me to do,” she said. “And here I am doing something wonderful yet again.”

Mostly, they both just want to keep doing what they love – and they’ve managed to do it much longer than many who found fame but then turned into yesterday’s news. On this point, Love and Clayton are expressing an attitude that I’ve encountered in Invisibles again and again. Great heights of fulfillment and success can be achieved by focusing on the value of your work, not the amount of attention you receive for it. And often the best way to advocate for oneself isn’t to spend time on self-promotion, but to simply “do the work,” as Clayton puts it. It’s a message that Love is happy to back up. As she said, smiling, “here we are, 50 years later” still working.

Take a Step Back to Propel Your Career Forward

For my first real job after graduate school, I earned $26,000 a year as a full-time reporter. It wasn’t a handsome salary — in fact, I could barely live on it — but I was getting paid to write. That’s more than I can say about how I spend much of my time these days. For the launch of my first book, Reinventing You, I spent six months writing scores of articles and blog posts for various outlets, and giving talks at universities, bookstores, and businesses — a great deal of it for free.

And yet, despite the irony that, in some ways, I’m still doing my old job but without a paycheck, I’m now making (depending on the year) up to 10x more than my old salary. As Internet theorist Doc Searls has described, instead of making money “from” writing, I’m now earning it “because of” the exposure it provides me and the related opportunities generated in public speaking, consulting, and teaching executive education. On one hand, I’m moving backward: blogging (oftentimes) for free is pretty lame for a former professional journalist who has been writing for nearly 15 years. On the other, I’m more successful professionally and financially than I’ve ever been. What I’ve discovered in this age of disruption is that for many of us, the reason we’re not moving forward as fast as we’d like is, ironically, our fear of going backward.

If you really want to move forward successfully in today’s economy, it’s important to think long-term. In his recent bestseller about the hotel industry, Heads in Beds, Jacob Tomsky writes about his early days doing valet parking and other unskilled jobs. Thanks to cash tips, the money was good — the advancement potential, not so much. When he was tapped for a management position, he had a difficult choice to make. He’d be earning less money in the immediate future, but his long-term career prospects would dramatically improve. He ultimately agreed to move into the white collar ranks, but his dilemma highlights an important point.

The kind of dramatic professional advancement we’d all like to see — big promotions, the opportunity to work on high-profile projects, or access to interesting opportunities — only come around when we’ve made an investment in our careers. And that investment almost always involves foregoing short-term gratification and, indeed, appearing to take a step backward.

When it comes to moving your career forward, it’s important to set aside your pride. In Reinventing You, I profiled a successful retired HR executive named Deborah Shah. She had decades of experience behind her. But when she became interested in political campaigns, she was willing to start at the bottom, where the campaign needed her. She made phone calls so reliably and effectively, they soon recognized her abilities and asked her to become a regional field director, launching a new career.

You also need to weigh the opportunity cost. A consultant friend of mine spent months building relationships, doing research, and preparing a proposal to work with the UN. It’s a slow process and — if the contract failed to come to fruition — would have to be viewed as a massive waste of time and money. She was perfectly aware that time spent chasing this contract was time she wasn’t spending on other new business development. But she was willing to take that risk, because she knew that being able to claim such a prestigious global entity as a client would dramatically elevate her firm’s reputation.

We hear all the time from innovation and startup gurus that we have to be “willing to embrace failure.” What that really means is you must be able to afford to fail. Failure is expensive — in time, reputation, and money. But over time, the willingness to take chances (that may fail) is an investment in your future success. If you want to move your career forward, a long-term orientation, a willingness to subsume your ego, and a clear understanding of the choices you’re making will help you advance, even if — temporarily — it appears you might be falling behind.

Guess Who Doesn’t Care That You Went to Harvard?

Sorry, Ivy League-educated dilettantes: While that framed degree may look mighty fine on your wall, most business leaders aren't particularly keen on your academic credentials when hiring, at least according to a new survey from Gallup. Consider the proportion of respondents who ranked each of the following factors as “very important”: knowledge in the relevant field, 84%; applied skills in the field, 79%; college major, 28%; and place of education, just 9%. Additionally:

+ Everyone, including Gallup, points to Google when discussing the knowledge-over-pedigree issue; Thomas Friedman's recent column on the company's five hiring attributes is generating a lot of buzz, though there's a big distinction between "knowledge" and "expertise," the latter of which Google isn't interested in at all.

+ This brief write-up from Quartz reveals a related, and startling, fact: 96% of college provosts say students are prepared for the job market. Yet only 14% of the public and 11% of business leaders agree.

It All Started With MagnetsBuckyballs vs. The United States of AmericaInc.

Craig Zucker is an entrepreneur prone to making suggestive advertising puns about a simple product that made him millions — tiny, round magnets that stick together to form interesting shapes. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, or CPSC, is charged with protecting consumers against dangerous products. The CPSC decided that Zucker's Buckyballs are just that after several children suffered lasting intestinal damage from swallowing them. Zucker, in turn, provided clear warning labels on the packaging and didn't market his product to children. But that didn't stop the incidents, or the controversy.

The contentious litigation that's ensued — the CPSC eventually sued Zucker specifically, which is almost unheard-of — brings up complicated questions that bridge safety and entrepreneurship. "Every time a new product like Buckyballs arrives," writes Burt Helm, "a decision must be made. Do we keep this new thing and warn against the dangers — like we do with balloons, trampolines, and plastic bags? Or do we banish it?"

They Don't Involve Your Ego Leadership Skills for the Year 2030 The Washington Post

Perceiving that businesspeople are worried about such things as the accelerating pace of change, the consulting firm Hay Group did a study of the megatrends that will shape leadership over the next dozen-plus years, and in so doing they gave businesspeople plenty of new things to worry about. Such as: Are you too egocentric to succeed as a leader in the future? In a Q&A, a regional director, Georg Vielmetter, explains that what will be needed is altocentrism — focusing on others, being emotionally open, using empathy to lead, and not putting yourself at the center of things. You'll also want to develop personal relationships with crucial individuals, because the future will be all about networks. It's a world that will fit well with the attitudes of millennials, who are less interested than previous generations in managing people. That's perfect: The leaderless company, not-led by people who don't want to lead. —Andy O'Connell

Buses vs. Trains Are Women 'Forced' to Work Closer to Home?The World Bank

In the "This is fascinating but we don't quite know what it means yet or what to do about it" category comes new research from Shomik Mehndiratta at the World Bank: While the average commute time for men and women in Buenos Aires is almost identical — 47.47 and 47.10 minutes, respectively – a closer look reveals that men travel at faster speeds than women. This means that men cover larger distances, and, presumably, have broader swaths of employment opportunities, particularly compared to the women in the survey who have children. In fact, when researchers mapped their findings, they found that "in parts of the city, men with children have access to over 80% more jobs than their female counterparts."

What Are You Great At? Shedding the Shackles of Judgment for Better Decision-Making Insead

If you've been piling on the self-criticism in your efforts to get ahead, you're probably on the wrong track. Although many of us believe, deep down, that negative self-talk is what keeps us in line, research shows the opposite, writes Schon Beechler of Insead. It's the "learner" in us, rather than the "judger," who fuels our success, and we can choose which of these selves to invoke. Instead of looking at what you might be doing wrong or whether you're good enough for your job, ask, "What am I great at? What works? What are my choices?" Questions such as these help turn off the punishing self-talk that strips you of confidence. —Andy O'Connell

America's Gargantuan Share of Global Wealth, in One Map (Time)

Science Explores Our Magical Belief in the Power of Celebrity (Smithsonian Magazine)

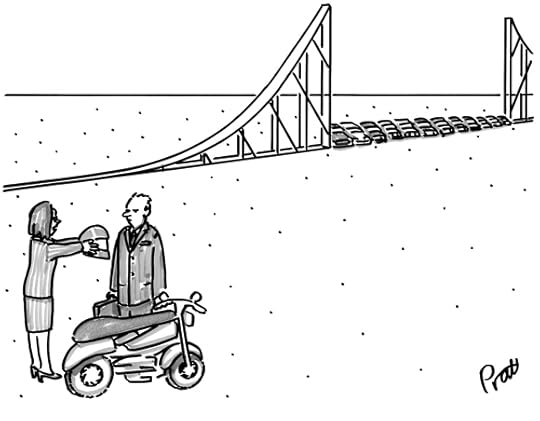

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the April 2014 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the April issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Cartoon Caption Contest at the bottom of this post. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in the next magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“This passive-aggressive stuff is getting to me.”

P.C. Vey

“I appreciate your concern, but I’ll be fine. I always leave a trail of breadcrumbs whenever I venture in there.”

Crowden Satz

And congratulations to our April caption contest winner, John Gregor of Edmonton, Alberta. Here’s his winning caption:

“Thanks for the dramatic reenactment of our quarterly growth chart, but you could have used PowerPoint.”

Cartoonist: Susan Camilleri Konar

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your own caption for this cartoon in the comments below — you could be featured in the next magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for the prize, please submit your caption by March 13.

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

Stop Pretending That You Can’t Give Candid Feedback

We’ve all heard the famous bromide that “honesty is the best policy.” But when it comes to performance feedback, honesty often falls by the wayside. Many managers hide behind performance management checklists or water down their feedback with generalizations. And on the other side of the equation, employees tend to position themselves in the most favorable light possible in their self-assessments, and avoid giving constructive feedback to the boss, even when it’s requested. The result is a lack of candid dialogue between boss and subordinate — which not only prevents the organization from improving, but also stymies individual development.

The odd thing about this phenomenon is that everyone knows that performance feedback should be more candid. There are hundreds of articles about the value of candid assessments and most supervisory and management courses include some variation on how to have “courageous” conversations (corporate-speak for “honest”). There also are some organizations, such as GE and (the new) Ford under Alan Mulally, that insist upon it.

Research also shows that employees are far more engaged when they receive honest feedback; and that leaders who rate highest in managerial effectiveness are those who most actively seek feedback from others. Yet performance feedback continues to look like the Emperor’s New Clothes, where everyone pretends that it’s different than it is.

The reality is that candid, two-way dialogues are intensely uncomfortable and cause anxiety on both sides of the table. The boss, for example, often worries that too much candor might be hurtful or damaging. As one senior manager said to me, “If I tell this person what I really think, it could destabilize her and make it difficult for her to do her job.” At the same time, the boss may also want to be liked by the subordinate and doesn’t want the relationship to deteriorate, especially if they have to work side-by-side. So it’s easier to pull punches than to say something that might damage the relationship.

On the other side of the ledger, subordinates worry that negative feedback will adversely affect their job continuation, career prospects, or earning power — so they may appear defensive or anxious, which makes it even harder to have an honest conversation. And if the manager asks for feedback, many subordinates will try to say nice things as a way of currying favor, or signaling a quid-pro-quo arrangement of “I’ll give you positive feedback if you give me the same.”

The net result of all this angst and (largely unconscious) anxiety is a stilted, pro-forma, ritualistic, and not very productive pattern of dialogue about performance. It’s a pattern that adds little value to the organization or to managers and employees.

Unfortunately, given the powerful nature of the underlying psychological forces, it is difficult to break this pattern. Most people believe Jack Nicholson’s line from the movie, “A Few Good Men,” when he shouted: “You can’t handle the truth!” That doesn’t mean that there’s nothing you can do. On the contrary, given the enormous value that more honest feedback can produce, here are three suggestions that might be worth exploring:

Acknowledge and discuss the difficulty of honest performance feedback. Whether you are the boss or subordinate, initiate conversation about the issue, the underlying psychology, and the value of getting it right. Use this blog post or other articles like it as a way to get the discussion started. The more you can build awareness of the dynamic, the better your chances of dealing with it.

Separate developmental feedback from job-security issues such as compensation and promotion. The easiest way to do this is to conduct these discussions at different times (even if your corporate process wants you to do them together). Doing this allows you to focus the conversation on how you and your subordinate can better accomplish key goals and projects — so the discussion is more work-related than “personal.” Making this explicit division removes some of the emotion from performance assessment and might free you up to be more candid.

Like any good skill, you need to practice. So don’t wait until the formal process kicks in and you’re under the gun to fill out forms and have a high-anxiety performance review. Instead, engage your people (or your boss) in a series of mini-discussions about how things are going and what can be done differently. The more frequently you have these conversations, the more comfortable they will become.

Honest performance feedback is not easy. But learning how to do it well can make a huge difference both for you and for your organization.

A “Bad Dream” Can Make for Great New Ideas

The CEO of an autonomous region for a multinational called with a problem. “We’re too successful,” he said. “We’re number one in the country, not only within my company but across the entire industry. Take your pick of the metric — profit, market share and customer satisfaction — we win.”

So what was the problem? Their current success was due to innovations and strategies put into place three years ago. Since then, everything had just purred along. Given that they were constantly lauded as examples of best practice, he was finding it difficult to motivate the senior managers to innovate for tomorrow’s success. In his words: “It is difficult to drive change when everybody is patting you on the back.”

Complacency like this is hard-won, but damaging and difficult to tackle. We began by talking with the CEO to identify the foundations upon which the company’s success was built – and discussing why these could ultimately lead to its demise. The CEO then agreed to leverage a classic tool – a disruptive scenario, but with a twist.

The CEO gathered twenty of his top managers at a secluded retreat, where he described how he’d received advance notice of a super-competitor’s imminent arrival. The tension grew as he described a competitive threat that targeted the heart of their business model.

Tension heightened as leaked advertisements and price plans were circulated. After a few moments of genuine panic, the CEO said: ”You are my top management team. We have a month. Tell me what to do.”

After the initial shock dispersed, (one participant actually said “this feels like a bad dream”), the managers formed cross-functional teams. Slowly solutions started to emerge. By the end of the day, there were many ideas, and some guarded optimism that the threat could be controlled.

As night fell, the CEO took the floor. I have two things to say. “First, the threat I told you about today is pure fiction. I made it up to provoke our thinking.” Confusion quickly gave way to relief. “Second, you’ve generated some highly innovative ideas. Which should we put into practice anyway?” Numerous initiatives emerged over the next twenty four hours. The shock of the “bad dream” had been central to helping the company extend its leadership for many years to come.

The CEO had taken a risk by not telling his team that the scenario he presented was fabricated — and in fact that it had been solely created to challenge his team’s implicit assumptions. And yet we have seen this approach work at multiple companies in different settings.

This “bad dream” approach works the best under these conditions:

First, the bad dream usually needs both outside input and senior management support. It is very difficult for an outside consultant to make the dream realsitic enough if the story is not championed by a high profile, embedded insider.

Moreover, the bad dream must be colorful. It must be embellished with personalities, quotations, documents, and other snippets of reality so that the participant feels that it is real. It must provoke an emotional reaction. Fear, excitement, shock, and desparation are vital to breaking sucessful managers out of complacency.

An effective bad dream is typically fairly complex, involving by multiple variables — consumer trends, emerging technologies, competitive threats, and regulations. After all, if the challenge is too straightforward, it doesn’t feel very challenging (or very realistic).

Typically, a bad dream is best placed in the medium term; one-to-two years horizon is best. This is near enough for the threat to feel real and disturbing, and yet not so near, that the actions are too tactical or knee-jerk.

Finally, this exercise works better when sprung upon managers with an element of surprise. This reduces the time they have to question the story. Instead they focus all available resources to innovate their way past the threat.

History suggests that the seeds of failure are often sown in times of great success. Little warning signs just off the main radar are too easily dismissed. This happens for many reasons; but a fundamental one is this: We are very good at lying to ourselves when it comes to our own success. We assume that if something good happened, we must have caused it — but dismiss setbacks as bad luck, a phenomenon that has been studied since at least the 1970s. We therefore miss the signals that we need to change. The bad dream is one of many tools that can help address this imbalance.

Can a President’s Happy Talk Hurt the Economy?

It’s known that fantasizing about an ideal future makes individuals decrease their effort, but can the same effect be seen on the scale of a national population? After studying U.S. presidential inaugural addresses, a team led by A. Timur Sevincer of the University of Hamburg in Germany concluded that the answer is yes: Positive thinking about the future, as expressed in these speeches, predicted declines in GDP over the subsequent presidential term. Happy talk may prevent people from preparing for difficulties, the researchers say.

February 27, 2014

Why So Many Emerging Giants Flame Out

John Jullens of Booz & Company says multinationals from China and other emerging markets must learn to innovate and manage quality while remaining nimble. For more, read “How Emerging Giants Can Take on the World.”

Take a Walk, Sure, but Don’t Call It a Break

Every weekday morning, I take a three-and-a-half mile walk around my neighborhood, in pretty much whatever weather my New England town throws at me. I split an apple and give half to each of the horses at the corner of Cross Street. The sounds of their chomps and slurps fill me with vicarious happiness.

When I was a kid I walked to school every day with John Flaherty, Doug Casey, and Rollie Graham. At the end of the day, after debate practice, Bill Bailey, Paul Salamanca, and I would walk home. We never stopped talking for a minute, and we could have used another hour each day to say all that was on our minds.

Part of the reason I created the Breast Cancer 3-Days, a charity walk, back in 1998, was to offer women with breast cancer and their supporters the luxury of having three days to converse, to daydream, and to imagine—without any of the aggravation of day-to-day life intruding.

But we’re wrong to think of walking only as a way to calm the mind, a source of exercise, or as a leisurely luxury. When it comes to work, walking can dramatically increase productivity. In a very real sense, walking can be work, and work can be done while walking. In fact, some of the most important work you may ever do can be done walking.

Last year I gave the closing talk at the 2013 TED Conference. The talk has been viewed nearly three million times and is now one of the 100 most-viewed TED talks of all time. I rehearsed the talk entirely on icy-cold morning walks over the course of about two months last January and February. Far from a luxury, I dreaded those walks, because my rehearsing was hard work. The productivity of that hour was so dense—it was mentally exhausting. Had I stayed home, chained to my desk, where most of us are taught that real serious work happens, the work would have been easier—but far less productive. I’d have gone online every few minutes to check a favorite news site. Grabbed a chocolate chip cookie or a glass of water. Checked my e-mail. Walking affords no such distractions. It’s just you and the work.

A 2013 study by cognitive psychologist Lorenza Colzato from Leiden University found that people who go for a walk or ride a bike four times a week are able to think more creatively than people who lead a sedentary life. The British Journal of Sports Medicine found that those benefits are independent of mood. Sunlight also boosts seratonin levels, which can improve your outlook.

These findings are absolutely true for me. The first mile of my walk is just a racket of competing voices of judgment and to-do lists. But after about two miles, no matter how low my mood may have been at the outset, those voices settle down.

Henry David Thoreau said famously, “Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.” The endorphin increase that comes with climbing hills makes the ideation that happens almost predictable. There are particular spots on my walks at which the ideas begin popping into my head, as if dropping from a magic tree on the side of the road there. Many refinements in essential phrases or visuals for my TED talk came to me at that spot.

But it’s work. The ideas don’t come unless I’ve engaged with the issue at hand. If I had U2 blaring in my ears, which would be a lot easier, they’d stay buried or just out of reach.

Last year my company, Advertising for Humanity, was up against a final deadline for a big branding assignment for a major client, and after months of work the idea just wasn’t gelling. On a morning walk it came to me. The new campaign has been a huge success. Our creative team did a walk together a few months back for another major assignment. The road seemed to be far more effective than a whiteboard for distilling the problem down to its essence. The clearing we created led to yet another big idea that has been a phenomenal success.

Walking is great for professional heart-to-heart talks. When I was running a large business in Los Angeles, I would often take employees on walks down Sunset Boulevard to talk things out. Biographer Walter Isaacson noted that walking was Steve Jobs’s preferred way to have a serious conversation. It’s not a break. It’s a change of scenery, but it’s work. The walking just makes it more productive work. The movement makes the conversation less stiff, more authentic, more responsible, even.

So, when you really need to get something done, get away from your computer and your conference room, and go for a long walk. It’s not a luxury. It’s work.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers