Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1463

February 25, 2014

What Data-Obsessed Marketers Don’t Understand

Big data has become the X factor of modern marketing, the hero of every marketer’s story. But it’s a promise at risk of letting you down. You may be thinking that data will magically turn bush-league marketing into a winning “Moneyball” performance. But that’s an artifact of our big data obsession. Data, alone, isn’t what makes marketing move the needle for business.

Data can play a leading role in developing strategy and bringing precision to execution, but it does nothing — absolutely nothing — to stir motivation and create the desire that makes cash registers ring. Data is important, but it’s content that makes an emotional connection.

That’s why we believe today’s data-obsessed marketers are at risk of cultivating only half a brain. Marketing leaders must remember that true brand intelligence lives at the intersection of head and heart, where the emotional self meets the analytical self.

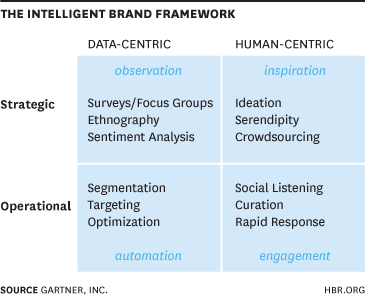

After working with numerous marketers, we developed the Intelligent Brand Framework to provide a structure for thinking about marketing investments across creative and operational disciplines, using a combination of data-driven and human-centric approaches. Its goal is to ensure that marketers don’t blindly focus on any one area without due consideration for the implications and tradeoffs to the organization’s broader goals. The goal is to help marketers find balance.

The Framework spans four domains representing basic marketing competencies:

Data-centric is where data sources come together to help us see patterns, make predictions, take action, measure results, and correct courses to optimize strategies.

Human-centric is where data may play a role, but patterns are discerned and action is taken primarily through human judgment, emotion, intellect, and moments of inspiration.

Strategic is the domain of the “what” and the “why,” where marketers use a combination of data- and human-centric practices to hone in on the best ideas.

Operational is the domain of the “how,” where marketers use automation and human beings to deliver the right offers and experiences to the right customer at the right time toward the goal of optimizing engagement and conversion rates.

But it’s the intersection of these domains that reveal the real strategic leverage points that represent the advanced competencies of the modern marketer. They are:

Observation is where customer behavior reveals new insights. These insights are found through traditional methods such as focus groups, surveys, panel and census data mining, and emerging approaches such as digital ethnography and text analysis.

Engagement is where impersonal brand messages become more authentic human dialogues. Here, marketers engage in social interactions to surprise and delight customers and, ultimately, to humanize a brand.

Inspiration is where moments of human genius are captured, indexed, and harvested for strategic advantage. Marketers use gamification, crowdsourcing, natural language processing, and collaboration to tap into the collective intelligence of human beings.

Automation is where machines allow us to achieve new levels of speed and precision by using data to target offers and experiences across channels and analytics to close the loop for continuous optimization based on measured effectiveness.

P&G, for example, is known as a pioneer in the observation category. It uses focus groups and advanced ethnographic techniques to tune in to the voice of the customer. IBM is a well-known example of an organization that harnesses inspiration with innovation jams that crowdsource the best ideas from the wisdom of crowds. Online retailers such as Zappos use automation to turn deep customer knowledge into personalized experiences as customers traverse the purchase path. Finally, companies such as outdoor retailer REI combine social listening with real-time engagement to build human-scale dialogues on the path to loyalty and advocacy.

Reflect on your collective capabilities as an organization. Where is your power center? Which quadrant represents your unfair advantage by way of capabilities, culture, and organizational maturity? Which quadrants reflect your organizational liability? Where are you weakest today? How are your competitors positioned, and where are they likely to grow and expand?

Begin to inventory your capabilities, investments, and challenges in each quadrant to reveal a picture of your current-state brand intelligence — and to create a playbook for your future-state brand leadership.

Critiquing your capabilities through the lens of the Intelligent Brand Framework helps keep you balanced in an age of short-term thinking and silver-bullet expectations. It’s designed to protect marketers from the unintended consequences of data-driven marketing — where an obsession with theoretical models can lead to misjudgments of human factors, such as overly familiar and frequent engagement or lack of authenticity in messaging.

If you are like most marketers, you may be at risk of becoming like the day-trader who is so dialed in to his data that he fails to see the patterns forming beyond the intraday trading bell. You may be at risk of simply asking too much of data.

February 24, 2014

The Best Way to Defuse Your Stress

I knew that I probably shouldn’t send the email I had just written. I wrote it in anger and frustration, and we all know that sending an email written in anger and frustration is, well, dumb.

Still, I really wanted to send it. So I forwarded it to a friend, who knew the situation, with the subject line: Should I send this?

She responded almost immediately: Don’t send it tonight. If you feel like you need to send it tonight, then I think it is for the wrong reasons. Make sense?

Yep, I responded. Thanks.

Three minutes later I sent it and bcc’d her.

She was flabbergasted: You changed your mind that fast?!?!?

Nope, I responded. My mind is in total agreement with you. But my mind didn’t send the email, my emotions did. And they feel so much better!

Most of the time, I’m professional, focused, empathetic, thoughtful, and rational. But that takes effort and, periodically, I lose that control. I might write an inappropriately aggressive email. Or raise my voice at my kids when they don’t listen. Or lose my temper with a customer service rep on the phone who seems to be missing my point.

It might look like I have an anger problem, but I don’t. I have a stress problem. I can be tightly wound. And, as a result, quick to anger.

In those moments when my stress erupts, my rational mind doesn’t stand a chance. It’s like trying to use intellectual arguments to talk down a stampeding bull.

Reason and stress speak different languages. Reason is intellectual; stress is physical. Reason favors words; stress prefers action. Our minds can advise us all they want, but our bodies have the upper hand. In fact, the more our minds try to curtail our stress, the more volatile it becomes.

If you pause to feel your stress, you will recognize it, quite literally, as energy flowing in your body. We live with that energy all the time, and, typically, it’s useful — it keeps us fresh, on our toes, and ready for action.

But, periodically — and I would argue increasingly — our stress levels rise well beyond useful. And, when that happens, we can easily lose control of our actions.

Think of stress as a monster, who lives in your body and feeds on uncertainty. The monster’s most satisfying meal starts with the sentence: “What will happen if . . . . ?”

What will happen if that presentation fails? What will happen if one of the projects I’m working on runs into objections? What will happen if I don’t have enough time to finish my budget? What will happen if my explanation doesn’t satisfy investors? What will happen if the company doesn’t get its financing?

As the uncertainty grows, so does the monster. Eventually, the pressure to escape the confines of your body proves too great. At that moment, you open your email, read something that annoys you and BOOM!

Here’s the interesting thing: after the explosion, we relax. Sending that angry email felt great. The monster escaped.

But not without consequences: The reaction of the person who received my angry email? That’s another story.

The question we need to answer is: How can I release the pressure without doing damage in the process?

Many of us try to manage or ignore our stress. We attempt to push it down, put it aside, breathe through it, or rise above it. But that’s a mistake. All those responses only encourage the monster to grow unfettered and, usually, unnoticed. Eventually, without fully understanding why, we get sick or explode or burn out.

There’s a better solution: Don’t try to manage your stress. Instead, dance with it.

The monster wants out? Let it out. But do so on your terms. You may need to cope for a moment, just until you can get to a place where you have privacy. Then, when you know there will be no adverse consequences, let the monster have you. Free yourself to kick and scream and punch. Feel what it’s like to completely lose control.

Recently I was having a hard time keeping it all together while I was in the car with my three children, whom I love to no end and who are also amazingly skilled at pushing my buttons. I held it together long enough to drop them off at our apartment. Then, when I was alone in the car, I let the monster take over. I yelled and cursed and screamed and hit the steering wheel over and over again.

It wasn’t pretty. Anyone looking at me through the window would have thought I was crazy. But by the time I returned to the apartment, I felt completely rejuvenated. And, most importantly, I was able to be a good parent.

I’ve yelled into the woods, repeatedly slammed my fists into my mattress, and jumped up and down stomping on the ground like an infuriated five year old. In places where people might be nearby, like office spaces, airplanes, or hotels, I’ve gone to the bathroom to have quieter hissy fits, jumping up and down and shaking without letting my voice rise to high.

If you really can’t get any privacy, then, instead of email, open your word processing program and write everything you’d like to say in that angry email. Let yourself go, punching the keys hard as you type, using all the pissy language you’d like to. Let the monster roam free.

Then delete the file, straighten your clothing, and be professional.

Stress is, ultimately, about trying to control that which you can’t. So trying to control your stress is one more thing that increases your stress. Physically releasing the stress on your terms helps. The point is to create an intentional and safe doorway for the stress to escape before it explodes.

It wasn’t long before I received a response from the person to whom I had sent my angry email, and she was clearly annoyed. I had flexed my muscles and she flexed hers back. This time, though, I was prepared. I went into another room, where I was alone, and shouted and jumped and punched into the air. After a few short moments, I felt powerful and balanced. Then I did what I should have done in the first place: I picked up the phone, called her, and had a reasonable conversation.

This is the third post in a blog series on taking control of stress. Peter Bregman is a contributor to the HBR Guide to Managing Stress at Work.

Read the other posts here:

Post #1: How Couples Can Cope with Professional Stress

Post #2: When a Vacation Reduces Stress — And When It Doesn’t

American Competitiveness Demands Immigration Reform

Most Americans — and both political parties — have come around to the view that attracting skilled immigrants is good for the U.S. economy. The Republican immigration reform principles released this month noted the thousands of foreign students studying at U.S. universities and called for retaining “these exceptional individuals to help grow our economy.” President Obama in his State of the Union address said, “when people come here to fulfill their dreams — to study, invent, contribute to our culture — they make our country a more attractive place for businesses to locate and create jobs for everybody.” The news that immigration reform may not be progressing this year is bad news for immigrants but even worse news for American companies.

There is wide recognition that we must fix our immigration system, but the many ways in which more open immigration would help build the economy are still not fully appreciated. Many immigrants are inventors or entrepreneurs, and the best ones excel at math and science at a time when companies are crying out for those skills. But the real secret sauce is the variety of experiences, language, and culture that recent immigrants bring to U.S. companies. In a global economy, it is increasingly clear that the country with the most educated, diverse pool of qualified talent will win. A more sensible immigration policy is critical for making that happen.

A strong and growing body of research shows that diversity on teams — especially at the leadership and decision-making levels — drives greater marketplace innovation and profitability. Not only does the conflict and intersection of different backgrounds, ideas, and perspectives create better business outcomes and solutions to almost any problem, they also ensure better understanding of customers and end users. The perspectives and intuitive customer insights that come from having diverse employees — particularly employees who share cultural connections with customers — is real competitive intelligence. Companies with employees that represent the end user are more likely to develop innovative products and services that meet the needs of customers in markets around the world. Having global, cultural, gender, and generational diversity is a serious business asset that confers significant competitive advantage in the global marketplace.

And it’s essential to the U.S. economy that American companies compete successfully in foreign markets. Exports have been among the strongest components of U.S. growth in recent years; they surged 11.4% in the fourth quarter of 2013. Many of America’s most profitable and important companies are heavily dependent on overseas revenue. Fifty-four percent of GE’s revenues come from overseas, as do 51% of Ford’s, 41% of Boeing’s, and 26% of Wal-Mart’s. Overall, about 46% of the revenues of S&P 500 companies (PDF) come from outside the United States.

Yet, as much success as American companies have had overseas, they also face huge challenges. U.S. companies have had some spectacular failures abroad — in Latin America, India, and especially China, where the enormous consumer market offers tantalizing upside. Apple’s smartphone share has been surging in China, but it still trails Asian companies like Samsung and Lenovo. Home Depot failed trying to bring American DIY sensibilities to China where there was neither the need nor the interest. eBay also missed the mark in both India and China by misunderstanding the nature of local relationship-driven transactional culture. Wal-Mart and others have struggled to succeed in Latin America.

Much of the insight and global perspective American companies need to be competitive can be found on U.S. college campuses. Last year, 70% of the graduate electrical engineering students in the United States were foreign-born, as were 63% of computer scientists and 60% of industrial engineers. This puts ready pool of highly-educated, English-speaking professionals from all over the world at our fingertips. Once hired, diverse foreign students bring both academic credentials and personal insights to the workplace. But without improved immigration regulations, some of these students would be headed home after graduation.

Consider the following example. At one major American healthcare company, a mid-level, Argentine-born manager was tapped by her peers in headquarters to turn around lagging sales in Latin America. It was immediately obvious to her that the company’s strategy left out local influencers in the academic world that would be critical to the sales process in the region. While her Latin America–based colleagues had been trying to push for a more local strategy for years, it took someone working within the U.S. headquarters to make a difference. After months of coordination and collaboration with the New Jersey–based leadership team, she was able to successfully persuade the company to allow a totally different, locally relevant sales strategy for Latin America. It wasn’t long before sales turned around and eventually soared.

This company was lucky to have such an employee. Then again, she had been lucky enough to get her green card years earlier after meeting her American husband at a prestigious American university. Had that not happened, she most certainly would have returned to Argentina and become a competitor, rather than a collaborator.

Most of America’s biggest companies across sector and industry, including GE, Exon, JP Morgan, Apple, General Mills, Goldman Sachs, Google, and EY, have large-scale focused diversity initiatives aimed to attract a globally diverse talent pool. But they are hampered in this effort by the current immigration system, which has high hurdles for even the most skilled foreign workers. As a result, many of the best foreign students and professionals with the skills and insights to make a real difference inside U.S. companies are forced to return to their countries with their newly minted American degrees. Tight quotas on green cards and limited numbers of temporary work permits mean that, as the House Republicans put it, “we end up exporting this labor and ingenuity to other countries.”

The immigration proposals on the table in Congress would do much to end this talent waste. They would lift the restrictive quotas on Indians and Chinese, increase the number of H-1B visas, allow spouses of H-1B holders to work (no small matter), and offer new visas for entrepreneurs. In short, they would allow American companies to field a diverse array of talent that no other country can match. In the economy of the twenty-first century, that’s an advantage we can’t afford to miss.

Why Is an App Worth as Much as a Small Oil Field?

Since Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp, commentators have debated whether the app was worth it or not. What if I suggested that the best place to look for answers could be the shale oil fields of North Dakota?

While on the surface, the dirty business of fossil fuels is nothing like Silicon Valley, many in the oil business have moved beyond the standard net present value (NPV) model for assessing the merit of investments. If you’re evaluating the rights to new shale oil reserves in a place like North Dakota, today you’d rely instead on a different economic model: option value.

I have to credit Rodrigo Canales of Yale for turning me on to the theory of option value, which looks at investments not based on revenue versus cost, but on how they increase the options available to an organization. Because this framework places a premium on investments that increase a firm’s options at the expense of their competitors’, it’s particularly suited to highly volatile industries.

So yes, Facebook has paid a lot for WhatsApp and its nearly half a billion users. But Facebook has also bought itself time to figure out how to extract value from that audience. And Google, widely rumored to be the other bidder, has lost those options and will have to settle for smaller reserves instead, perhaps acquiring one of the less-dominant players.

You can think about WhatsApp’s user base as a reserve, similar to the oil in a shale field: we know it’s there, but it is not yet clear how much value Facebook can recover. In both cases, technology increases the efficiency with which they can extract value out of this “deposit” should increase over time. In the oil business, this might mean something like fracking. In the tech business, the equivalent is mobile and increasingly contextual advertising, the primary source of value for titans like Google and Facebook. And, I would argue, it is also user experience – the ability to bring as much value to the surface of the product as possible. Whoever figures this out quickly has an opportunity to race quickly ahead in the mobile boom.

Consider the rapid progress Facebook has made on mobile, not only domestically, but in emerging markets. I just returned from a two-week visit to South and East Africa, where just a few years ago the business community was wondering whether Facebook would ever “get” mobile. And yet now, according to a number of experts I spoke with, FacebookZero represents more than 30% of the data traffic on many networks in the region. With the acquisition of WhatsApp, they are positioned to be the dominate player for years to come – giving them unheard-of leverage with the mobile operators who are the primary gateway to internet access for billions of people coming online for the first time. Talk about options!

I know that comparing social media to the oil industry is not going to make me any friends. And there would seem to be some critical differences, as there is a limited amount of fossil fuel in the ground, while new social networks and messaging services seem to be cropping up endlessly. But attention is quickly emerging as a scarce resource and Whatsapp seems to occupy a very strategic position in the communications landscape. Proximity is everything in both industries.

If you are willing to entertain this metaphor for a moment, it allows you to survey the online landscape with new eyes. Video, photo-sharing, gaming, internet radio and messaging represent massive reserves of attention. In most cases it seems that only a handful of platforms emerge with the ability to tap these reserves, largely based on the quality of their user experience.

And rarely do these platforms emerge organically from within a Google or Facebook these days.

So, to preserve their option value, the big players must invest before the valuations for Instagram or Youtube have stabilized. They are betting on the future value, not just of these platforms, but of the additional options that they will create for their organizations. We have seen this play out successfully with Youtube, whose value to Google extends beyond the video sharing service itself by increasing the value of Plus, Chrome, Android and many other properties.

So the big question is not is $19 billion too little or too much. The big question is: where are the biggest untapped reserves of attention online? Where would you drill if you had money to spare?

Understand the Sacrifices Before Launching a Start-Up

Making the decision to found your own business is a life-altering experience. Of course, it’s what comes after that breakthrough moment – how unique the idea, how quickly you move, how you continue to innovate – that ultimately separates the wheat from the chaff.

And whether you’re in the culinary arts, book publishing or cloud technology, when you become an entrepreneur, work-life balance becomes a thing of the past. Your work must subsume your life if you want any shot of making it big.

There’s a reason why many compare starting a technology company to having a baby. In doing both, you’ll need to make sacrifices. You’ll inevitably miss important commitments. You’ll pull many all-nighters. You’ll be stretched past your limit. The most important thing is that you need to be okay with those changes – and internalize them before their force becomes overwhelming. What’s more, your family and those immediately surrounding you must also be onboard. In most cases, you’re risking everything you have for your idea, and they need to be prepared to support you and do whatever it takes to allow your idea to reach its potential.

There’s no sugarcoating it. It’s not easy. However, if you get in the right mindset and surround yourselves with the right people, venturing out on your own is also one of the most rewarding things you can do in life.

Making Sacrifices

It’s common knowledge that you’re going to have to make sacrifices to be successful. For me, weekend trips became a thing of the past after starting our company Okta. As a big skier, I head to Snowbird in Utah each January with other entrepreneurs to hit the slopes. But the needs of my company became the top priority during these vacations, and I spent the entire weekend of our trip in 2010 in the hotel room closing our first round of funding – and was unable to let my friends know what was going on because some worked in venture capital. I missed the 2011 ski trip entirely due to business, and I’ve missed four close friends’ weddings in foreign countries since founding Okta. My co-founder Todd McKinnon and I have given countless weekends, early mornings and late nights to talk with customers as we build and grow our company.

At the time, there was no question about whether or not I would miss the weddings, or whether or not I would spend my ski trip indoors. Like a baby, our business’s needs come first. Internalizing these decisions was part of building our company and making sure it became successful. If that meant changing my mindset to reorient it toward our business, then that was what I was going to do.

A Strong Inner Circle

It’s common knowledge that the people you surround yourself with during the startup process can make or break your business, but there are a couple of people that will make all the difference.

My co-founder, Todd McKinnon, and my wife, Sara Johnson Kerrest, help me cope with the strain that comes with being an entrepreneur more than any well-prioritized to-do list ever will. As my business counterpart and my counterpart in every other way, the two of them make up my inner circle – confidants that are always there when I need to bounce around ideas or ask tough questions others may be afraid to. And they’ll be there for every risk you need to take.

Todd and I are very lucky that we have such supportive spouses – though when we both decided to leave stable positions at Salesforce.com to start something from scratch (with no revenue stream in sight) just after Sequoia Capital said “RIP Good Times,” tough questions had to be asked.

For Todd, that meant presenting a very text-heavy, yet persuasive PowerPoint to his wife. For me, that meant convincing my then fiancé (and now wife) that it was the right thing to do. Your family is there to ask the tough questions, but it’s encouragement and reassurance from your close friends and family that can make the difference when you start a business.

Things Change As You Grow Up

Of course, the sacrifices you make change as your company grows, too. Collaborating as a team of two is much different than managing a company of 300+, and that means you are going to have to make changes to how you work and also to how your work impacts your personal life.

It may mean no longer needing to review every line of code, and instead, taking those nights and weekends to build out an engineering team. It may mean no longer giving your cell phone number out to every customer as the sole company support person, and instead, giving your cell number out to every member of your new customer support team. It may also mean exchanging the speed of getting things done for the increased process required for automation and scale – and while these types of workflow changes can be some of the most challenging to internalize, they are the ones that ensure your company is able to continue growing.

It also means adapting your professional endeavors to fit with your personal life. When I co-founded Okta, I was engaged. Now I’m married with an 8-month-old at home. I make different sacrifices than I did when I first started. I still work 16 hours days, but no longer work both days of the weekend (or at least not regularly). I don’t watch many San Jose Sharks games on TV because when I do get home, I’m spending time with my son — or catching up on sleep.

While the sacrifices I make now are different, the care of my first baby, my business, will always be a priority, so whether it’s missing out on weddings, hockey games or the appropriate amount of sleep, giving up something is a given. But like having a child, it can be one of the most rewarding things you ever do.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

How to Thrive While Leading a Family Business

The “Older” Entrepreneur’s Secret Weapon

Why One Executive Quit Business Travel Cold Turkey

Walk Your Way to More Effective Leadership

How to Get Over Your Inaction on Big Data

It’s common to see surveys, polls, and reports showing that “most” organizations are embracing big data. For instance, a 2013 Gartner survey found that 64% of enterprises were deploying or planning big data projects, up from 58% the year before.

But I find these numbers hard to believe, for three reasons. First, they contradict what I’m seeing in the field. Second, they’re inconsistent with the history of technology. Yes, we live in what Ray Kurzweil calls an era of accelerating technological change, but no transformative application or device has ever achieved critical mass within three years. Finally, as Bill Schmarzo of EMC points out, most organizations are still feeling their way into big data. They’re at the low end of what Schmarzo calls the big-data “maturity” spectrum.

I would wager that for every Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Netflix, and Google, there are still thousands of midsized and large organizations that are doing nothing with big data beyond giving it lip service.

One big barrier to implementation is the incessant noise around big data from consultants, vendors, and the media. The din leaves many, if not most, CXOs confused and intimidated. They wonder: Do we start small or large? Is big data just another IT project that can be run by a unit head? And what’s the ROI going to be, anyway?

To begin with, big data is not just another IT initiative. Traditional tools (business-intelligence applications, relational databases) simply can’t handle petabytes of unstructured information. Nor is it amenable to traditional discussions about return on investment. Outcomes of big-data deployment are inherently uncertain—predicting its ROI is an exercise in futility.

In fact, the beauty (and the horror, to some people) of big data is that you don’t know where it’s going to take you. You might discover fascinating and valuable insights. Or you might find nothing of interest—at least not yet.

That uncertainty doesn’t bother companies like Netflix, which exhibit a deep curiosity about their data. For example, Netflix goes so far as to analyze the color content of shows’ and movies’ packaging. If responses to certain colors or combinations are among the factors driving consumers’ choices among the company’s nearly 80,000 sub-genres of movies, Netflix wants to know.

The capabilities of companies on the mature end of Schmarzo’s spectrum are downright scary. But you can’t expect to go from zero to Netflix overnight. These firms have been capturing, storing, and analyzing massive amounts of data for more than a decade. During that time, they’ve followed a number of critical steps:

They’ve accepted that big data requires a large commitment throughout the organization. Doing big data right necessitates the full support of the leadership and everyone in the organization.

They’ve methodically built up their internal data repositories.

They’ve invested in new tools.

They think about big data’s ROI in holistic ways. Big data is not comparable to ERP and CRM applications. These suites lent themselves to traditional ROI calculations because they largely automated manual business processes. Rather than focusing on the costs of action, mature big-data users consider the costs of inaction. They don’t want to be playing catch-up to competitors that have figured out how to utilize new sources and forms of data. They’re painfully aware of the Matthew Effect.

If you’re starting on the big-data path, the first few months are critical. Look closely at your organization’s current data practices. If a company doesn’t do a good job of managing relatively small amounts of structured data, it isn’t likely to do well with big data. Does the company have a culture of making decisions based on data, or do politics, tradition, and policy rule the day? Is failure punished so severely that no one is willing to take risks?

These are all danger signs. If you squirm when reading this, don’t embark on the big-data voyage until your company has learned to manage small data well, has committed to basing its decisions on real information, and is agile and tolerant of risk-taking.

Assuming your company is ready to take on big data, the first year should serve as petri dish of sorts. What works? What doesn’t? Are certain data sources more valuable than others? Trying to do everything at once is never a good idea. It’s important to achieve—and communicate—little victories, such as getting employees to learn new tools and ask better questions of their data sources. It’s these victories that build the foundation for future insights.

It’s unlikely that your organization possesses the data and financial and human resources that Netflix does—but that shouldn’t dissuade you from embarking on your big-data journey, a point that I made in a previous post. A mere decade ago Netflix couldn’t collect, store, or analyze this type of information either.

So forget the ROI mind-set and the project mentality, and imbue big data into your overall business strategy.

The “40-Year-Old Intern” Goes to Wall Street

In mid-September 2013, 10 professionals returning from multi-year career breaks walked into 270 Park Avenue in New York City to begin the J.P. Morgan ReEntry Program. Elsewhere on Wall Street, Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse have recently initiated internship programs for return-to-work professionals. The Onramp Fellowship for returning lawyers, backed by four major law firms in 15 cities, opened for applications last month, and MetLife just announced a similar program to commence this spring.

In the six years I have been tracking return-to-work programs, I have never seen five, new, big-employer returning professional internship programs debut in such a short span. And last week J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s Head of Diversity Gordon Cooper told me his firm is now introducing a Legal ReEntry Program. (In full disclosure, Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, MetLife, Morgan Stanley, and Onramp Fellowship have all worked with my firm.)

In November 2012, I wrote an article for HBR about the emergence of returning professional internship programs across a wide range of sectors: for-profit, non-profit, military and academic institutions. At the time, Goldman Sachs’ Returnship was the only thriving, return-to-work internship program at a large company. To date, 123 “returnees” have participated in the 10 week Goldman program in the U.S., and roughly 50% have been hired into permanent positions. The three new Wall Street programs follow a similar formula to Returnship in terms of timing and small class size. All of the programs are paid.

The OnRamp Fellowship operates on a different model. Applicants pay a $250 fee to cover the cost of career development assessments, but those who are selected receive a $125,000 work and training fellowship, plus benefits, for their first year at one of four major law firms: Baker Botts, Cooley, Hogan Lovells, and Sidley Austin. Applications are being accepted until March 7 and fellowships begin this summer.

What triggered all of this activity? Why now? J.P. Morgan’s Cooper explains it this way: “Many companies are waking up to the incredible amount of untapped talent that has left Wall Street firms.” The Onramp Fellowship’s Caren Ulrich Stacy adds: “This year marks the fourth consecutive annual decline in the number of mid- to senior-level female associates in large law firms. We need a way to replenish this pipeline, and fast. The Fellowship was built to increase gender diversity in law firms while also giving women who want to return after a hiatus an opportunity to expand their skills, experience, and legal contracts as they re-enter.”

Now that the economy is stable enough for companies to look beyond the recession, we are seeing a renewed focus on building pipelines with the top candidates from all recruiting pools, including the returning professional pool. Forward thinking companies have long recognized that the return-to-work demographic, composed primarily of women who took time off to care for children, is full of high achievers. “This talent pool is especially strong, and we expect our Return to Work Program to uncover some exceptional individuals who will contribute greatly to the Firm,” says Susan Reid, Morgan Stanley’s Global Head of Diversity and Inclusion. At Credit Suisse, firm representatives characterized their Real Returns program as an “opportunity to connect with a highly skilled and untapped diversity pool.”

Recruiting professionals at the end of career breaks, when they are largely done with maternity leaves and spousal job relocations, is a smart strategy. The use of internships as a testing ground helps remove any perceived risk that some managers may associate with hiring from this pool, and gives the participants a gradual and structured ramping-up platform. The internship allows the employer to base the permanent hiring decision on work product and a longer opportunity to get to know a prospective employee, instead of a short series of interviews. As one hiring manager commented “I wish I could hire everyone this way.”

Why Raising Retail Pay Is Good for the Gap

Gap announced last week that it would increase its hourly minimum wage to $9 this year and $10 next year. Naturally, President Obama applauded the decision, which was in line with his own push to raise the minimum wage. But what Gap is after is not greater fairness or less income inequality. According to the chain’s CEO, Glenn Murphy, the reason for this move is that Gap implemented a “reserve-in-store” program 18 months ago, meaning that customers can order a product online and then pick it up at a particular store. Gap realizes that this program won’t work without skilled, motivated, and loyal employees.

This is hardly a surprise to me. Remember Borders bookstores? Almost 15 years ago, I studied Borders as it was trying to integrate its online store with its physical stores. Borders had great technology to tell online customers which book was available at which store. But there was a fatal hitch: the inventory data was not reliable. The system would tell a customer a book was in the store, but no one could find it. This happened 18% of the time! That’s way too many customers to let down and, in fact, Borders had to give up on the idea. Eventually, it went out of business.

Why were so many products not where they belonged? I found that stores that had fewer employees, less training, and more turnover had more of this problem. By going cheap on labor expenses, Borders made it hard to act on a strategic opportunity.

Borders is hardly alone in its lack of investment in employees and in the resulting operational problems. Most retailers follow what I call a bad jobs strategy. They see their employees as a cost to be minimized and invest very little in them. They pay poverty-level wages and offer unpredictable schedules that make it hard to hold a second job. They also design jobs in a way that makes it hard to do a good job; for example, to keep inventory data really accurate.

They don’t realize how much they lose this way. Retail stores are complex operating environments. A Gap store can have thousands of products, most of them in many sizes, and there are different places where they might be found—not only the shelves where they officially belong, but fitting rooms, storage areas, and special promotional displays, not to mention random places where customers might have left them. Customers come in with different wishes and need different amounts of help. When companies try to keep such a complex environment running with employees who are unmotivated, poorly trained, or overworked because they are too few in number, the result is poor execution. Products are in the wrong place or have the wrong price. Data are inaccurate. Promotions are advertised but not carried out. Employees can’t answer customers’ questions—they may not know the answers or they may not have time.

Pervasive problems like these reduce sales, reduce employee productivity, and increase costs. And, as Borders and others have found out, they can make it impossible for a company to seize a strategic business opportunity.

Gap’s decision to pay its employees more is a step in the right direction, but only a step. It allows the chain to improve store execution and deliver great performance, but it won’t make those happen all by itself. If Gap really wants to deliver excellence, it will need to complement its increased investment in employees with smart operational choices that ensure that employees are as productive as they can be and that they can play a bigger role in driving sales and reducing costs.

I know this is possible because, as I did the research for my book The Good Jobs Strategy, I found a set of companies already doing it. Whatever it does for the income gap in general, offering good jobs to employees – while delivering low prices and great service to their customers and excellent returns to their investors – could turn out great for Gap.

What Microsoft Should Have Done Instead of Discounting Windows

On Friday, Microsoft slashed the price of Windows 8.1 by 70% for select B2B customers. The magnitude of this price cut was surprising; all that was missing was a pitchman screaming “If you call now, we’ll throw in a free Tae Bo workout DVD — a $29.95 value!”

Reasonable observers could be forgiven for asking: is Microsoft crazy? Not really – it had to do something as Windows’ sales are sagging. In FY14/Q2, sales dropped by 6% in the division that sells Windows software (Devices and Consumer Licensing). To counter this sales drop, Microsoft did what I call a surgical discount strike. Instead of the regular $50 per unit license fee, if you act right now the price is $15. The caveat is that this discount is only available to manufacturers that preinstall Windows 8.1 on devices that retail for less than $250. This discount is directly targeted to tablet makers (to be more competitive against iPads) as well as notebook manufacturers (to take on rivals that use Google’s Chrome operating system).

Kudos to Microsoft for not offering an across-the-board price cut – the move most companies would have made. For instance, when discount airlines started entering different markets, incumbent carriers typically panicked. They’d drop fares on all of their daily flights on the city pairs served by the discount airline. But as incumbents became wiser, instead of an everything-is-on-sale discounting approach, they’d only do so on flights that departed around the same time as the discount airline. In fact, they’d often add a flight that departed at the exact same time as the new discounter. That was an intelligent surgical discount that matched what the competition offered.

The downside of Microsoft’s price cut is that it devalues Windows 8.1 by placing a highly discounted number in the minds of manufacturers that sell devices priced over $250. If you were the CEO of a company that is paying $50 a license and now see that Microsoft is charging $15 for the same operating system to select customers, what would you do? While Microsoft may be the primary option today for high-end devices, were I that CEO I’d certainly demand a discount coupled with a veiled threat to work with Google to upgrade their Chromebook OS to be more applicable to fuller functioning products. For companies that enjoy large market shares – such as Microsoft – the thought of losing a major customer over price is cataclysmic. Trust me, I’ve been in those harried meetings. Ultimately, this limited discount means that Microsoft will eventually cave and start discounting Windows 8.1 to all of its customers.

This isn’t the first time that Microsoft has rolled out a less than optimal pricing strategy. In its recent game console war, I argued that Microsoft blew it by having a highly restrictive digital rights policy and charging $100 more for its Xbox relative to Sony’s PS4. Microsoft quickly reversed itself on the DRM and, despite criticism, held steady on its $100 premium (which included a Kinect wireless motionless control). The results are telling: Sony claims that its PS4 has outsold the Xbox by nearly 2:1. Just as impressive, Sony’s goal had been to sell 5M units by the end of March but in fact sold 5.3M PS4s by mid-February.

The situation Windows faces is typical. An innovative company creates a great product that is widely adopted and highly profitable. Drawn in by dreams of high margins, new entrants come in – typically with a less functional product – and attempt to siphon off price-sensitive customers. As a result, executives at the incumbent company lose sleep due to pricing pressure and start heavily discount their product. Then the price cuts destroy their profit margins. It’s truly a timeless story with an unprofitable ending — and a moral for companies facing stiff price competition.

What Microsoft should have done is rolled out a “fighter product” – a less functional operating system (say, Windows 8.1 “lite”) at a lower price – that is targeted to lower priced device manufacturers. Even easier, perhaps discount an older version, say Windows 7, and use that as the fighter product. The beauty of this simple versioning strategy is it serves a price sensitive market without devaluing a company’s flagship product. If high-end manufacturers complain about price, they are welcome to purchase the less functional version (which they won’t because it’s not appropriate for their products).

Despite what publicists write in carefully crafted press releases, aggressive competition is rarely good for a company’s bottom-line. In these sleep-deprived “we are losing sales now” situations, managers need to resist the Pavlovian urge to “cut-prices-now.” Rolling out a fighter-version is almost always the correct strategic response to combat discount rivals.

How Mayo Clinic Is Using iPads to Empower Patients

Throughout the world, companies are embracing mobile devices to set customer expectations, enlist them in satisfying their own needs, and get workers to adhere to best practices. An effort under way at the Mayo Clinic shows how such technology can be used to improve outcomes and lower costs in health care.

Defining the care a patient can expect to receive and what the road to recovery will look like is crucial. When care expectations are not well defined or communicated, the process of care may drift, leading to unwarranted variation, reduced predictability, longer hospital stays, higher costs, poorer outcomes, and patient and provider dissatisfaction.

With all this in mind, a group at the Mayo Clinic led by the four of us developed and implemented a standardized practice model over a three-year period (2010-2012) that significantly reduced variation and improved predictability of care in adult cardiac surgery.

One of the developments that germinated in that effort was the interactive Mayo myCare program, which uses an iPad to provide patients with detailed descriptions of their treatment plans and clinical milestones, educational materials, and a daily “To Do” list, and to report their progress and identify problems to their providers.

The Challenge

For cardiac surgery (as in many other practices) the cost of care is likely to exceed Medicare reimbursement. That was true in our Rochester, Minnesota, program, prompting us to examine our cost of care delivery. We examined the cost determinants in the operating rooms, intensive care units, and on the patient floor and found that unwarranted variation in the care process negatively affected the value of care (outcomes divided by cost).

The Solution

We then designed and spelled out all the steps of the optimal care model for routine cardiac surgery, which included identifying both best practices and ways that patients could become more effective partners in their own recovery. The new care model was demonstrated to be sufficiently robust by rapidly improving results and increasingly predictable outcomes for large segments of patients. With predictability, we were then in a position to share that information with patients and set expectations for participation. (We also theorized that telling patients what they should expect, would also drive provider adherence to the care model.)

We realized that empowering patients and setting their expectations required effectively providing the following to them:

A “Plan of Stay” that included a “Plan of Day” that outlined expected daily clinical milestones and provided a daily patient “To Do” list that was linked to their clinical status and the recovery events. The plan was configured uniquely for each patient based on his or her surgery, medical conditions, and pre-hospital functional status. (A screenshot of Day 2 of a typical Plan of Day is shown below.)

Modular Educational Materials about their surgery, their medical conditions, and expected care events each day events in the hospital. This education needed to be “just in time” and relevant to the needs and experience of the day.

Gaining Strength modules that set daily expectations for physical activities such as walking and breathing exercises and provided patients with tools to self-assess and report things like pain and mobility. This allowed us to tell patients how much they should walk each day, ask them how much they walked, and, using wireless accelerometry, measure how much they walked .

Recovery Planning information on how patients should care for themselves after discharge. For example, it included information on wound care, exercise and diet, activity restrictions, follow-up appointments, and potential complications and how to recognize them.

Source: Mayo Clinic

We speculated that an iPad was an ideal means to convey this information to patients and have them report their progress and problems to providers.

In addition to software development, we converted hundreds of pages of patient instructions and educational materials into videos, voice-over slideshows, and text modules that the software could deliver. An example is falls prevention in the hospital.

Implementation

When the Mayo myCare program went live in February 2012, we limited the participants to patients who were going to have elective cardiac surgery, had a predicted hospital stay of five to seven days, were older than 50 years, lived at home, and could walk. Participants had to speak and read English (because the program was only in English), could not have impaired vision, or suffer from dementia.

Prior to surgery patients were provided with an iPad and trained for 30 minutes in using the program by a registered nurse who then followed up with patients daily during their hospital stay to answer any questions they might have and make sure they understood how to use the program.

After the first 30 days of patient use, we evaluated patterns of program and content utilization by day, content type, and content format. We then modified the program to better meet patients’ needs. Our ability to track daily patient use, essentially in real time, allowed us to determine that we needed to reduce the total amount of content early after surgery and change the form of that content to make it more usable (video only) when patients were feeling poorly. We delayed providing more challenging content to later in the stay. And recognizing that a large number of patients had hearing impairment, we provided headphones with the iPad to all patients after the first 30 days of testing.

Before and after surgery, patients used the iPad to learn about the plan of day, work through their “To Do” list, and complete their daily education, self-assessments, and recovery-planning modules. The data was aggregated on a server in the cloud and configured into dashboards that the nurses and physicians caring for the patients could view.

Below is a screenshot of the patient dashboard, which includes a predictor for the need for discharge support, compliance with the care plan, daily self-assessment of pain and mobility, and completion of education and recovery-planning modules. “ESDP” means Early Screen for Discharge Planning, a tool that predicts a patient’s need for support after he or she is discharged.

Source: Mayo Clinic

A population and individual patient dashboard showed all patients on the care plan and provided alerts when patients were deviating from their plans. The providers could also click on an individual patient’s name to view a dashboard for him or her.

The program triggered provider interventions when: 1) a patient’s self-assessment tool predicted patients might require home health care or skilled-nursing services at discharge, 2) patients were not completing their daily education or recovery-planning modules, and 3) a patient’s self-reported mobility was too low or pain scores were too high.

Following discharge, patients were surveyed about their satisfaction with their hospitalization and surgical experience as well as their comfort in using the myCare program.

Results and Benefits

The average user of the program in its first seven months (from April to November 2012) was 68 years old. Of the first 134 patients that participated, 86% used the program to the end of hospitalization. The primary reasons the remaining 14% of patients dropped out were postoperative medical or surgical complications that prevented them from staying on the standardized care program or continuing program use (readmission to the ICU, patient confusion, or cardiac arrhythmias were most common causes).

The typical patient was provided with 67 care modules to work through over five to seven days, and patients completed more than 85% of them before they left the hospital. Patients did particularly well with the self-assessment tools, completing more than 97% of them.

About 70% of patients returned a post-discharge survey. More than 90% expressed overall satisfaction with their care, and more than 90% felt they were well informed about their care while in the hospital. More than 80% said they were very comfortable using the myCare program within a day or two of use, and 98% felt the program provided information that prepared them to better manage their own care after they left the hospital.

Preliminary data also suggest that patient education and participation through the myCare program can help shorten length of stay, reduce cost of care, and improve patient independence after leaving the hospital.

It’s difficult to estimate the costs to reproduce this elsewhere. While the custom software might be built for about $200,000, and iPads purchased for about 10% of that amount, Mayo’s greater investment lay in the clinical pathway the program supported, Mayo’s body of educational materials, the clinical algorithms behind the program, and the clinical experience and commitment of the providers who contributed to its design and testing. Those contributors included the four of us as well as “floor” nurses, education specialists, discharge planners, physician assistants, social workers, occupational and physical therapists and a patient focus group.

Remaining Challenges

The program was built specifically as a single-practice solution and was not integrated with our electronic health record (EHR), these limited its scalability and usability – fundamental requirements for new electronic health solutions. Recognizing those limitations, the success of the program, and the fundamental role of patient participation in evolving care models, Mayo is rebuilding the software platform so it can be used to create and deliver care plans in multiple types of surgical practices. The rebuild will populate the patient’s EHR with the data the program acquires and it will used at Mayo’s multiple sites.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers