Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1461

February 27, 2014

Use a Task Map to Improve Your Team’s Performance

If you’ve noticed your team is functioning unevenly and its esprit de corps isn’t what you’d hoped, it’s time for you to ask yourself whether your people are deployed optimally.

Employees’ skills and interests can evolve over time, as can the goals of your group, so misalignment can happen without your noticing it. That person who was hired to do analysis but has blossomed into a first-rate motivator and loves working with groups: Is he still stuck in front of a computer doing analysis? Is the employee who was recruited as a trainer feeling frustrated because she has no opportunity to take advantage of her extraordinary talent for writing?

I’ve found that there’s a powerful way to answer questions like these: Create a task map.

A task map is a visual tool that allows you to see where skills are lacking or duplicated on a team. It can help you assign tasks that will take advantage of each person’s abilities and interests. I’ve seen task maps lead to a boost in productivity and employee satisfaction through what seemed like minor shifts in responsibilities. I’ve also seen them lead to major transformations after leaders discovered they didn’t have the right people for the work at hand.

Helen, the head of Human Resources for an organization with more than 20,000 employees, realized that members of her leadership team had been performing inconsistently: They excelled in some aspects of their jobs while coming up short in others. Customer complaints were on the rise, and she noticed collaboration fading and competition mounting.

The first thing she did was assess leadership team members’ skills by looking at their past accomplishments and the results of 360-degree assessments. Next, she listed their primary, secondary, and tertiary abilities on a whiteboard. This allowed her to see redundancies and gaps that had arisen over time. For example, four directors were strong in analysis but only one had well-developed project-management skills. And although the group was responsible for educating thousands of employees each year, there were only two people with a talent for training and teaching.

Helen then created a list of the HR department’s divisions and the tasks required for each one. She began drawing color-coded lines from team members’ talents to the tasks for which those talents were suited. The result looked like a jumble of Pick-Up Sticks—it got so messy she didn’t even complete the exercise.

She saw immediately that some directors’ skills were not well aligned with their current responsibilities. For example, Alex and Chris were better suited to each others’ positions. While both had experience as human resources generalists, Alex’s primary talents for writing and attention to detail were ideally suited for Chris’s work managing benefits and evaluating pay practices. Chris, meanwhile, was the only director with strong motivation skills and a customer-service orientation.

The need for a shift in responsibilities couldn’t have been more obvious. The extroverted Chris readily agreed to switch positions with Alex, because managing people played to his strengths and he found it much more enjoyable than managing contracts. Dealing with employees and clients had been draining for Alex, who found real satisfaction in performing detailed analyses and administering contracts.

The task map, even in its incomplete form, also revealed other imbalances that were not so readily solved, so Helen convened her team for a daylong meeting to redistribute the workload. Rather than make changes unilaterally, she gave everyone a say—a smart move, because the discussion led to a better all-around understanding of people’s skills and interests and engendered loyalty and goodwill.

The meeting led to a number of changes. For example, the team realized that HR’s increasing workload required the creation of two positions to handle logistics and program management. These new people would, in turn, free the directors to make better use of their own expertise.

After that pivotal session, Helen provided tools and training so that team members could succeed in their roles. The leadership team continued to meet regularly to make sure all members had ample opportunities to use their talents fully and to take on projects they enjoyed. (They also rotated responsibility for finding a fun activity for these quarterly sessions—their last meeting ended with a pool tournament.)

I checked in with Helen a year later. She reported improved performance and increased job satisfaction on the part of most of her directors. One person had left, which gave her an opportunity to fill a customer-service skills gap that had been identified in the initial task-mapping exercise. She created a second task map to visualize the changes. Not only had Helen better deployed her staff, the group had identified synergies across divisions and created opportunities for collaboration among directors. Afterward, several department heads, her key customers, told her they had noticed an improvement in the level of service her team provided.

Helen’s critical move in all this was focusing on deployment. She saw the daily harm that comes from allowing people’s abilities and responsibilities to become misaligned. She realized that people are happier and more productive if they have regular opportunities to use their skills and pursue their interests.

You may be surprised at the productivity and morale boost you can get from giving people some control over their work lives. Ensuring good alignment of skills and tasks creates an environment that encourages passion, productivity, and enjoyment, leading to sustained high performance and reduced turnover.

Ending the Shareholder Lawsuit Gravy Train

The Supreme Court is going to host a debate next week on the efficient market hypothesis. The battle lines may not be exactly what you’d expect: the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Justice Samuel Alito have already argued that the EMH is, as Alito put it, “a faulty economic premise,” while Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Obama administration have backed the idea that, as a sextet of Justice Department lawyers put it, “markets process publicly available information about a company into the company’s stock price.”

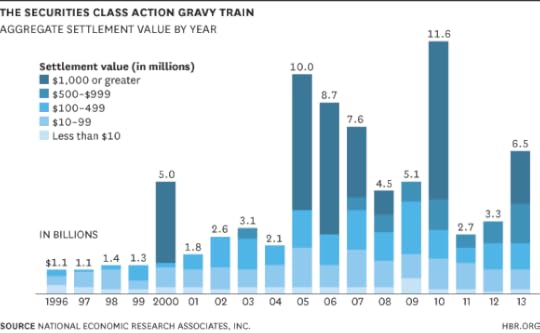

This debate is happening because in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., a case scheduled to go to oral arguments on March 5, the Supremes are reconsidering the “fraud on the market” doctrine at the heart of most securities-class-action lawsuits. These are the big-dollar shareholder suits frequently accused of endangering American economic competitiveness. They get less attention than they did in the 1990s and early 2000s (remember Bill Lerach, the “king of the shareholder class-action suit”?) but are still, as is clear from the chart below, costing companies a lot of money.

These lawsuits have been enabled in part by the efficient-market teaching that “in an open and developed securities market, the price of a company’s stock is determined by the available material information regarding the company and its business.” That’s from an appeals court decision approvingly quoted by Justice Harry Blackmun in his 1988 majority opinion in Basic, Inc., v. Levinson, the case that took the fraud-on-the-market standards that had been evolving in the appeals courts and consolidated them into the law of the land. Because prices reflect available information, that appeals decision went on, “misleading statements will therefore defraud purchasers of stock even if the purchasers do not directly rely on the misstatements.” That made it relatively easy to assemble a big group of plaintiffs, since all you had to do was find those who had bought or sold a company’s stock over a particular time period — whether or not they’d been paying any attention to the misleading statements of its executives. It also opened up the possibility of huge damage verdicts, as the stock drop after bad news finally came out could be seen as a first approximation of the loss to the defrauded shareholders.

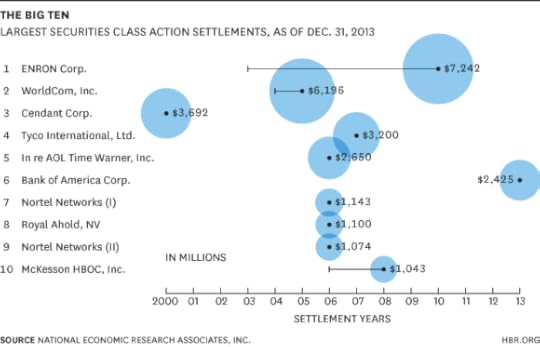

How huge? Here are the ten biggest shareholder class-action settlements of all time, as tallied by National Economic Research Associates Inc. in its annual report on shareholder suits:

It’s worth dwelling for a moment on who gets that money and who pays it out. In most cases it’s the current shareholders of a company paying current and former shareholders. The corporate executives who made the misleading statements generally don’t pay anything at all because they’re covered by directors & officers liability insurance. In the two biggest settlements, the offending companies — Enron and WorldCom — went belly up, leaving their banks stuck with most of the tab, a somewhat more logical outcome but not the standard one. Then there are the lawyers. In the Enron case the plaintiffs’ attorneys got $798 million in fees and expenses; with WorldCom $530 million. The percentage take tends to go up as the settlement amounts get smaller — overall, NERA reports that plaintiff’s attorneys pocketed $1.13 billion, or 17% of settlements, in 2012. Defense attorney costs are harder to get at, but indications are that they add up to another 10% or more of settlements. In short, then, shareholder lawsuits amount to a weirdly circular process in which presumably blameless outside investors hand over money to other outside investors (and sometimes to themselves), with the executives accused of wrongdoing left untouched and the lawyers for both sides taking a big cut.

As a result, University of Pennsylvania law professors William W. Bratton and Michael L. Wachter wrote in 2011, a consensus has developed among academics that fraud on the market is “not just flawed, second-best, misdirected, or in need of improvement, but flat-out senseless, mindless, and reasonless.”

Just because most law professors think something is a bad idea, though, doesn’t make it go away. Fraud on the market now has decades of legal precedent on its side, plus a 1995 law passed by Congress that was intended to rein in shareholder suits but didn’t address fraud on the market (more on that in a moment). The one obvious thing that has changed since the Basic decision in 1988 is that the strong academic consensus around the efficient market hypothesis that prevailed then has weakened considerably — as evidenced by last year’s Nobel prize in economics, which was shared by the author of the efficient market hypothesis, its leading critic, and a third scholar who developed statistical tools for testing market efficiency.

For a business-friendly Supreme Court that has been nibbling around the edges of shareholder suits but had until now avoided taking on fraud on the market directly, this debate seems to have provided a window of opportunity. But if the economists on the Nobel committee can’t decide whether financial markets are efficient, we probably shouldn’t expect America’s highest court to. “The Supreme Court is not really the body that’s best situated to referee that kind of dispute,” says Stanford Law School professor Joseph Grundfest, who as founder and principal investigator of Stanford’s Securities Class Action Clearinghouse follows this stuff as closely as anybody. “I don’t think we want Supreme Court justices reading back issues of Econometrica and deciding which coefficients are asymptotically efficient.” What’s more, as Harvard Law School’s Lucien Bebchuk and Allen Ferrell recently wrote, none of the many academic criticisms of the efficient market hypothesis actually refute the basic idea (or Basic idea) that misleading statements can distort a company’s stock price.

In short, there are probably some things wrong with the Basic decision’s reliance on the efficient market hypothesis, and there are almost certainly some things wrong with the ways lower courts have interpreted it, such as the much-used Cammer test of market efficiency devised by a U.S. District Court judge in New Jersey in 1989. But that’s not the main thing wrong with fraud-on-the-market lawsuits, and it may not be central to what the Supreme Court decides.

Grundfest figures the Court will instead focus on the areas where it has comparative advantage — judicial precedent, textual analysis, legislative intent, that kind of stuff. Not that this necessarily simplifies anything. Legal scholars have churned out a staggering volume of work on shareholder lawsuits in recent years, and the small percentage of it that I’ve read (it took me several days) doesn’t lend itself to easy conclusions. It does, however, paint a fascinating picture of how we’ve landed in this predicament. So I’ll conclude with seven fun facts for you to recite at your next fraud-on-the-market-themed cocktail party, culled mostly from Georgetown University Law Center Professor’s Donald Langevoort’s “Basic at Twenty: Rethinking Fraud on the Market” and William & Mary Law School Professor Jayne Barnard’s “Basic, Inc. v. Levinson in Context”:

In 1942, the Securities and Exchange Commission, fleshing out a section of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, adopted Rule 10b-5, which spelled out that it was unlawful “to engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person, in connection with the purchase or sale of any security.”

In 1964, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that (I’m quoting Barnard here) “in order to effectively supplement the often-overwhelmed enforcement efforts of the Securities and Exchange Commission, it would recognize an implied right of action, enabling private investors to seek damages and other relief under … the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.” In 1970 it provided for the award of plaintiff’s attorney fees in such cases, and in 1971 it upheld a Rule 10b-5 case. So the whole securities class-action thing was basically a creation of the Supreme Court, with Congress and the SEC playing supporting roles.

These decisions led to a doubling in the number of securities lawsuits filed in federal courts from 1970 to 1975, after which the Supreme Court, now with a majority of Nixon and Ford appointees, began making it harder to file shareholder lawsuits in federal courts. For time the lawsuit tide ebbed, then the frenzied Wall Street activity of the 1980s and the rise of fraud-on-the-market theory in the lower courts sent the numbers back up.

Then came Basic, Inc. v. Levinson. For reasons that nobody seems to know, conservative Justices William Rehnquist and Antonin Scalia sat the case out. Also, Justice Lewis Powell had retired and his replacement, Anthony Kennedy, wasn’t confirmed in time to take part. As a result, the Court’s four-man liberal minority of Blackmun, William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, and John Paul Stevens found itself in the majority — and provided the votes for the decision.

Basic, Inc., a “maker of chemical refractories for the steel industry” (Harry Blackmun’s words), got a raw deal. The plaintiffs’ complaint was that Basic executives misled investors in 1977 and 1978 by repeatingly denying that they were involved in merger negotiations with Combustion Engineering, Inc., “a company producing mostly alumina-based refractories,” then announcing in December 1978 that they had agreed to a merger. It was the reverse of the usual shareholder class-action complaint — in this case it was the people who sold early, and missed out on the merger premium, who claimed to have been defrauded. But Basic’s executives argued, and the District Court judge agreed, that they hadn’t misled anybody at all. They had gotten occasional nibbles from Combustion Engineering over the years, but never took them seriously until receiving an offer in December 1978 at a far higher price than anything that Combustion had previously mentioned. The appeals court opted to ignore this defense, and so did the Supremes.

Fraud on the market got crucial backing early on from conservative University of Chicago Law School scholars Frank Easterbrook (now a federal appeals court judge) and Daniel Fischel, both big believers in the efficiency of markets and the need to defend it. “The law should protect markets; markets will then protect investors,” is how Langevoort summarizes their thinking.

In 1995, a Republican Congress passed — over President Clinton’s veto — the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, which was intended put a damper on the securities class-action party. As it turned out, the PSLRA didn’t reduce the number or severity of such suits, but there are some indications that it cut back on nuisance filings and led to a better (that is, more serious) sort of shareholder suit. It did not directly address fraud on the market. In a brief filed in January, several then-members of Congress and staffers (all Republicans) explained that the House had considered constraining fraud on the market but gave up in order to assemble a veto-proof majority, while the Senate didn’t formally address the issue at all.

It Matters Which Avatar You Choose When Gaming

Research participants who had played a 5-minute computer game using a Superman avatar were subsequently kinder to other people, and those who had played as the evil Voldemort were less kind, say Gunwoo Yoon and Patrick T. Vargas of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. After the computer game, the participants were instructed to provide an unspecified amount of chocolate and hot chili sauce to other people who they believed would be required to eat it all (untrue); those who had been “Superman” provided about twice as much chocolate as chili sauce, while those who had been “Voldemort” did the reverse.

To Get Honest Feedback, Leaders Need to Ask

“The only way to discover your strengths,” wrote Peter Drucker, “is through feedback analysis.” No senior leader would dispute this as a logical matter. But nor do they act on it. Most leaders don’t really want honest feedback, don’t ask for it, and don’t get much of it unless it’s forced on them. At least that’s what we’ve discovered in our research.

We have the benefit of rich data thanks to the more than seventy thousand individuals who have completed the Leadership Practices Inventory, our thirty-item behavioral assessment, over the years. The point of this tool is to help individuals and organizations measure their leadership competencies and act on their discoveries. Looking across how all observers of leaders have filled it out, one descriptor got the absolute lowest rating – and even across the leaders’ own self-assessments it comes out second to lowest. It is this statement: “(He or she) asks for feedback on how his/her actions affect other people’s performance.”

When we related this finding to the director of leadership development for one of the world’s largest technology companies, he admitted the same was true for his organization. The lowest-scoring item on its internal leadership assessment was the one on seeking feedback.

Further validation comes from a recent survey conducted by Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman and discussed in a recent HBR blog. Not only did they find that “leaders often don’t feel comfortable offering [constructive criticism].” They also discovered that the individuals who are most uncomfortable giving negative feedback are also significantly less interested than others in receiving it.

Why is this? Sheila Heen and Douglas Stone offer this answer in a recent HBR article. “The [feedback] process strikes at the tension between two core human needs — the need to learn and grow, and the need to be accepted just the way you are. As a result, even a seemingly benign suggestion can leave you feeling angry, anxious, badly treated, or profoundly threatened.” For us, this resonated with something that author Ralph Keyes once wrote about his craft: “As authors discover, all the other anxieties — the many courage points of the writing process — are merely stretching exercises for the big one: feeling exposed (in every sense of the word).” A friend of his, he reports, “compared writing novels to dancing naked on a table.”

What’s true for writers is equally true for leaders. Leaders aren’t eager to feel exposed — exposed as not being perfect, as not knowing everything, as not being as good at leadership as they should be, as not being up to the task. And subordinates are even more reluctant to suggest that the emperor is wearing no clothes.

So what’s a leader to do?

It won’t be enough to increase your receptivity to others’ input. It’s highly unlikely that your direct reports, or peers, are going to knock on your door and say, “I’d like to give you some feedback.” If you want a genuine assessment of how you’re doing, you’re going to have to make the first move and ask for it. That’s what leaders do, by the way: Go first.

That’s exactly the approach taken by a vice president we met at a leading Midwest financial services company. He knew the value of direct personal feedback for his own and others’ growth and development. Yet for his team members, the whole topic of feedback “had a big negative tone to it.” He decided it would help if he reversed the traditional process. “We’re going to do things a little bit different,” he told the group. “Instead of me giving the evaluations, you’re going to start by doing one on me.” After a brief orientation, he left his team to evaluate his performance in private. They were reluctant at first, and the process was initially very challenging. But eventually the team completed it, and then, at the vice president’s request, the team delivered their feedback to him face-to-face.

“The feedback that I received was kind of hard to hear,” he told us. But then he added: “And that was really one of the benefits to the group. To take that personal risk — to model for the group that it’s okay to place yourself at personal risk and take that honest feedback. What I hope the team members would come away with was a sense that it’s okay to be in that environment, that feedback is necessary for growth, and then to see how you accept that feedback and then what you do with it.”

This executive provided the proof of how vulnerability can build trust. Because of his ability to ask others for help, his team gained a newfound respect for the feedback process — and so did he.

Feedback Framed as Learning

Getting valid and useful feedback is essential to learning. And learning is the master skill. Over the years we’ve conducted a series of empirical studies to find out if leaders could be differentiated by the range and depth of the learning tactics they employ. The results of these studies have been most intriguing. First, we find that leadership can be learned in a variety of ways. It can be learned through active experimentation, observation of others, study in the classroom or reading books, or simply reflecting on one’s own and others’ experiences.

What is more important, however, is that regardless of their learning styles, those leaders who engage more frequently in learning activities score higher on The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership (our evidence-based model of effective leadership) than do those who engage less frequently in learning. The truth is that the best leaders are the best learners.

Feedback is too often viewed through a frame of evaluation and judgment: Good and bad. Right and wrong. Top ten-percent. Bottom quartile. These frames raise resistance. But when you frame feedback as an essential part of learning, it becomes less about your deficiencies and more about your opportunities.

The late John Gardner, leadership scholar and presidential adviser, once remarked, “Pity the leader caught between unloving critics and uncritical lovers.” No one likes to hear the constant screeching of harpies who have only foul things to say. At the same time, no one ever benefits from, or even truly believes, the sycophants whose flattery is obviously aimed at gaining favor.

To stay honest with yourself, you need “loving critics.” These are people who care about you and want you to do well — and because they care about your wellbeing, they are willing to give you the honest feedback you need to become the best leader you can be.

Appoint your own circle of loving critics. Turn to them regularly for an honest and caring assessment of your strengths and what you need to do to get even better. Listen to them with the same care they have for you. And when they give you their feedback, your only job at that moment is to say “Thank you.”

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Don’t End Your Career With Regrets in Your Personal Life

What Does Success Mean to You?

Understand the Sacrifices Before Launching a Start-Up

How to Thrive While Leading a Family Business

February 26, 2014

The Dark Side of Retirement

A retired CEO, Jerry was a sad, aging man who reflected constantly on the emptiness of his life. Listening to him, it became clear to me that he had never had any interests outside work. And the prospect of spending time at home with a partner who seemed to have turned into a stranger made him all the more depressed.

For people like Jerry the public recognition that accompanies a position at the top of an organization becomes the most meaningful dimension of their lives. Their life anchors are their identification with an institution of great power; influence over individuals, policies, finances, and the community; and constant affirmation of their importance as individuals and of their role as leaders.

With retirement, all these anchors disappear from one day to the next. The destabilizing effect is often exacerbated by a realization of what has been lost, or sacrificed, years earlier, on the way up to the top: a fulfilling personal life; a good relationship with a spouse, children, and friends; and time to develop outside contacts and interests. That’s one reason why many top executives delay retiring and cling to power for as long as they can.

Other hidden but potent psychological and emotional factors also conspire to make retirement difficult. To begin with, people usually attain top leadership positions just when the effects of aging become more noticeable. When top executives look in the mirror, the face frowning back at them from the mirror shows the ravages of age, unleashing a wave of negative emotions: fear, anxiety, grief, depression, and anger.

Self-consciousness about the deterioration of the body (a sense, almost, of being defective) can stimulate the search for substitutes for attractiveness and virility. For some people — and top executives are prime candidates, given the prestigious positions they occupy — wielding power is a gratifying substitute, becoming a replacement for lost looks. Small wonder that so many are reluctant to let go. If the power of office is the only thing they have left, they will hold onto that office as long as they can.

Another complicating factor for those faced with the prospect of relinquishing power is the talion principle. Derived from early Babylonian laws it states that criminals should receive the like-for-like punishment for injuries inflicted on their victims. Leadership involves making difficult decisions that affect the lives and happiness of others — positively, but also negatively. Because of their unconscious belief in the principle, leaders file all those decisions in a memory bank and, as the number of “victims” mounts, so does the expected retaliation. This makes them extremely defensive and provides another incentive not to retire.

It’s inevitable that top executives who have placed work at the center of their entire adult lives will be devastated when power dynamics shift and a named-but-not-yet-in-office successor begins to win converts to his or her very different dream for the future of the organization. Like an old lion they will lash out in an attempt to put ambitious ladder-climbers in their place. The wit who said the primary task of a CEO is to find his or her likely successor and kill the bastard had a point: that “bastard” stands to destroy the outgoing CEO’s most cherished dreams.

These fears are accentuated by the need all of us have to leave behind a legacy: leaving a reminder of one’s accomplishments can be equated symbolically with defeating death. Many top executives question whether their successors can be relied on to respect the monument that took them so long to build.

Most companies are woefully negligent in their understanding of the psychological dynamics of retirement. The default mode is simply to abandon people on the verge of retirement, giving them little or no help in preparing for such a critical life change. There is, I feel, an opportunity here. No one can stop executives from aging, but companies can give them a transition to retirement — and help themselves in the process.

The case of Ronald, former head of Asia of a global information technology firm, illustrates what companies can do. In this company, the VP for talent management had been very eager to offer special work arrangements for hard-to-replace, experienced executives approaching the mandatory retirement age.

With the support of the group CEO, she had introduced a flexible, phased retirement policy that allowed senior executives approaching normal retirement age to reduce the hours that they worked, or work for the organization in a different capacity after retirement. It gave retirees the opportunity to transition gradually, in contrast to the abrupt termination common in many companies.

In this instance, Ronald became a special advisor to the group CEO with a brief to help develop the company’s African markets. The arrangement not only helped the Group CEO to develop a strategy and organization for a fast-growing region, it gave space for both Ronald and his wife to experiment with non-workplace activities without having him leave the workplace altogether. What’s more, Ronald and his wife had always had a special interest in Africa, making Ronald’s ongoing work something both could engage in.

Arrangements like Ronald’s are win-wins for both companies and retirees. Given the damage that can be caused by a powerful executive’s struggle to retain power and remain relevant, managing slow retirements could be at least as important as onboarding new hires quickly.

Coping Techniques for Lonely Change Leaders

Leading change in large organizations is hard work and offers little instant gratification. To sustain the energy to lead that change, innovators must take proactive steps to protect their psyches. Many commentators on innovation focus on the substance and approach to work; however, they abstract away the mental grit needed to cope with what often can be a lonely existence.

Below, I draw on my experiences leading change efforts in sectors and institutions as varied as the government (the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services), academia (Harvard University), and industry (Merck) to describe some ways in which the innovator can sustain the passion needed to lead real change in complex organizations. The lessons I describe represent my views and are not the positions of the organizations where I’ve worked.

Maintain conviction. When joining an organization or stepping into a new role as a change leader, it is easy to believe that your job is to learn the ropes and conform. It’s often easier to feel like your job is to fit in and not to stand out. While some acculturation can be helpful, too much can undermine your real value: fresh perspective. If you have conviction, you’ll be recognized as a leader who leads with principle. Otherwise, you run the risk of “merely regressing to the mean,” as one CEO with whom I’ve worked describes it.

Avoid haters. In any large organization you will inevitably meet individuals who love to hate. Hating comes in many forms — undermining whispers, scolding for not having followed defined process, and backhanded praise — and often is cast as “trying to help.” Confront your haters with facts if they are misinformed, but otherwise ignore them as they are an endless drain on your energy. When I began in one role, I found myself trying hard to placate a group of individuals who did not support our change agenda; I learned after repeated attempts that they never would — and would only continue to waste precious time and energy and slow our momentum. Never miss an opportunity to learn about what you can do better, but also take a moment to consider the source and motives of your critics.

Cultivate a support system. Challenging an organization’s status quo never comes without frustration even in the very best of circumstances when organizations have declared a need to change. Surviving through the inevitable challenging times requires colleagues who understand both you and the organization. A robust support system will contain a mix of individuals who have the real power to help when you need it most and others who can lend perspective and remind you of the big picture when you inevitably lose your way. In my current role, my support system includes a mix of colleagues at peer companies, friends who intimately understand my personal strengths and weaknesses, sage senior leaders at my company, and members of the team I lead. The complementary perspectives always get us through times that test our resolve.

Celebrate success. When organizations are engaged in stressful and fast-paced change efforts, often the first things to go are celebrations of success. Celebration takes many forms: memos to recognize fellow leaders, parties to take a break from hard times, awards and bonuses to staff that have made a difference. Celebrating yourself and others will help you appreciate the many milestones that exist on the path to making sustainable change and keep you fresh for the next challenging situation ahead. When I worked at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Don Berwick, its administrator at the time, would almost daily take a few moments to send e-mails of thanks to frontline agency staff. The lift in morale from these small forms of recognition was palpable — and contagious.

Innovating in large, complex organizations carries with it the promise and potential of large-scale, wide-reaching impact that is hard to achieve in smaller, less complex settings. Yet the work is sometimes frustrating — with rewards that often are not apparent. Building the personal reserve to cope with and manage through the inevitable challenges that one will encounter in these settings will be the difference between making merely an incremental mark and leading lasting change.

Will Spanish Help You Reach the U.S. Hispanic Market? It Depends

The Hispanic market will represent $1.5 trillion in purchasing power by 2015 and 30% of the U.S. population by 2050. Business leaders who are contemplating how to reach such an enormous market segment, especially through their digital presence, often ask me the same question: “Do we really need Spanish, or can we get by with just English?”

A study from the Pew Hispanic Center shows that 82% of Latino adults in the U.S. speak Spanish, and 95% believe it’s important for future generations to continue to do so. Likewise, the National Hispanic Consumer Study found that advertising in Spanish can boost both advertising effectiveness and customer loyalty.

In contrast, AOL’s Hispanic Cyberstudy found that Spanish-dominant Hispanics gravitate toward sites that are in English, not Spanish. Why? For one thing, English sites are simply what’s on the web for the U.S. audience. Another factor is that Spanish-language sites targeting U.S. Hispanics are often riddled with poor translations and a user experience that is not culturally relevant.

If you want to market to online Hispanics effectively, you want to do it right. Here are a few ideas on good strategies:

1. Create a customized domain for Hispanics. Increasingly, companies are registering domain names that are distinct from their English sites to ensure an authentic look and feel. For example, McDonald’s has a separate site for Hispanics, www.meencanta.com, a play on its “I’m lovin’ it” phrase that still sounds memorable and positive in Spanish. Avoid simply using a subdomain, or you may be sending the message that the Spanish site is less important than the top-level domain from which it stems.

2. Don’t just translate, “transcreate.” On the McDonald’s Hispanic site, the content is completely customized for its target market, integrating games, songs, Hispanic celebrities, and themes that are more relevant for this group. Because creating brand new content can be expensive, many companies take a hybrid approach, leveraging translations of some of their English content while also using transcreation to generate content that is unique and culturally relevant. Wherever possible, you should avoid just translating your English-language content into Spanish without having a Spanish-speaking editor or other expert review that copy.

3. Offer bilingual versions of the transcreated content. Develop your Hispanic web content in a bilingual and bicultural way that represents your business. Provide the culturally relevant content in both languages. Allowing users to toggle back and forth also facilitates multi-generational purchasing.

4. If all you have is a translated site, don’t neglect it. Perhaps you don’t have time or budget right now to develop custom content for Hispanics. Even so, that’s no excuse for leaving the “Copyright 2013” notice sitting on your site for all of 2014, or for failing to test your links on the Spanish site. These kinds of errors are surprisingly common even for major brands, but they send a clear and unfortunate message to Spanish-site visitors: “You don’t matter.” And machine-driven translations rarely offer a good quality product. Get your content professionally translated and reviewed. If you offer parallel sites in English and Spanish, make sure to treat your Spanish site with the same careful attention as your English site. Equal respect for your customers means equal respect for the content directed at them, no matter the language.

Remember, the payoff for offering in-language content is huge, especially in online settings. As a study from Common Sense Advisory found, 72.1% of consumers spend most or all of their time on websites in their own language. Similarly, 72.4% of consumers say they are more likely to make a purchase if information is available in their own language. Translating or adapting content to reach a new market makes your initial investment in the original content go even farther.

Don’t Let Your Career Cause Regrets in Your Personal Life

When I was in my early days as CEO of Quest Diagnostics, working hard to turn around a then-troubled company, my daughter suffered a life-threatening illness. She was a freshman in college in a distant city. As any parent would, I rushed to her bedside. As I stood there, contemplating her uncertain future, I was seized with regret, thinking about my frequent absences during her young life. I talked with her frankly about those regrets. Though I was relieved to hear her say that she felt I had always been there for her, I never again took for granted that the conflicts of work and personal life would somehow just work themselves out.

Now, on the other side of my stint as a CEO, what advice would I offer hard-driving executives about coping with those conflicts? Such advice is plentiful and familiar: Make time for non-work activities, exercise to reduce stress, learn to say “no,” manage your time more efficiently. All excellent ideas. And the vast literature on the subject contains many useful tips.

However, the truth is that there’s no magic formula, especially for CEOs or people in comparably demanding positions. What I would offer, instead, are some ways to think about the problem, some guiding principles to keep in mind over the long haul of a career:

Be realistic about work. In my experience, people make it to the top job by working extraordinarily hard. And once they get there, they find that there is no letup, especially today when investor expectations are higher than ever, globalization has made the position a round-the-clock job, and technology hardwires everyone to work. My guess is that burnout among CEOs is on the rise, although it’s difficult to document because they are precisely the kind of people who forge stoically ahead no matter what. But you must recognize that you cannot do everything. Otherwise, the results are likely to be both personally destructive and ultimately bad for the company.

Don’t expect perfection in personal life. At Quest Diagnostics, we turned things around, in part, by adopting Six Sigma, which aims at a standard of perfection. Unfortunately, personal life doesn’t work that way. Expect to fall short some of the time. Then try to do better. Think of it as continuous improvement but with your inner Deming on mute. It helps, of course, if you have loved ones who are understanding and neither hold you to an impossible standard nor let you entirely off the hook.

Change the metaphor. For decades, resolving the conflicts of work and personal life has been spoken of as a question of “balance.” Yet work and life are inextricably intertwined. Work supports our loved ones; it constitutes a big part of our identities, and it often shapes our social lives. The smartphones and other devices that bind us tightly to work also keep us in close touch with our non-work-lives. For example, I keep all of my personal and professional commitments on a single, integrated calendar, treating each one of them as inviolable. The challenge is to integrate work and personal life effectively, not achieve a separation that is less attainable than ever.

Be present. When you are with family or friends be fully there — in spirit as well as in body. No zoning out thinking about work. No relying on the discreet kick under the table calling you back to planet earth. On the other hand, don’t treat these personal encounters as you would a meeting, where you check in with each of your loved ones as you might with your executive team.

Don’t forget yourself. What often gets lost in the push and pull between work and personal relationships is your own well-being — body and soul. You skip your workout, delay your annual physical, rarely take up a book that’s not work related, and make no time for self-reflection. Mens sana in corpore sano — a healthy mind in a healthy body — remains advice that is both timeless and easy to ignore in favor of work or personal relationships.

In “The Choice,” the poet William Butler Yeats considers the consequences of choosing “perfection of the life, or of the work” and suggests that choosing the latter can exact a high personal cost and end in great remorse. Though perfection in either realm is unattainable, we do have the power to choose. In any given moment, we can decide what we are going to do — whether we’re going to give work its due or be fully present for our loved ones. We should count ourselves lucky that we do have a choice, unlike those who must work two jobs just to make ends meet.

Instead of feeling these choices are burdens or, worse, not a choice at all but a compulsion, we should celebrate them. Today, as dean of the Boston University School of Management, I engage in work that is both demanding and highly fulfilling. And I have a life that includes my daughter (who, thankfully, fully recovered) and son, three grandchildren, and my wife of 42 years. Who could ask for anything more?

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

How to Thrive While Leading a Family Business

The “Older” Entrepreneur’s Secret Weapon

Why One Executive Quit Business Travel Cold Turkey

Walk Your Way to More Effective Leadership

Why Your Business Might One Day Accept Bitcoin (or Something Like It)

Every day seems to bring a new headline about Bitcoin, the digital currency first created in 2008 by the pseudonymous programmer Satoshi Nakamoto. Yesterday’s news that Mt. Gox, the largest Bitcoin exchange in the world, will file for bankruptcy owing to the theft of nearly six percent of the world supply of bitcoins is a reminder that the digital currency is far from ready for primetime.

The price of bitcoin remains highly volatile, its merits as a currency are contentious among economists, and its popularity thus far is inextricably tied to illicit activity. Yet, interest in the “cryptocurrency” is rising, and while its user base may be small, a growing number of merchants are choosing to accept bitcoin as payment.

As The Washington Post’s Tim Lee has written, Bitcoin’s true potential may be as a digital payment protocol rather than as a true currency. In other words, Bitcoin’s problems as a store of value may not prohibit it from working as a medium of exchange, one that could ultimately prove attractive to businesses. To explore this potential, I talked to Jeremy Allaire, serial entrepreneur and founder of the video platform Brightcove as well as the web development language Cold Fusion. He is currently working on a company called Circle, which is building products to support the use of Bitcoin and other digital currencies.

Let’s start with Mt. Gox. Is this a significant setback for Bitcoin?

I like to say we’re in the “pre-Netscape” phase in the evolution of this technology and industry. The first wave of startups, who were frankly ill-prepared to take on the responsibilities that go with managing consumer financial products, are being weeded out. In their place, we are seeing a new generation of seasoned entrepreneurs, industry leaders and world-class venture capital backers build financial services that offer the benefits of digital currency along with the safeguards, scale and protections that are really required to earn and sustain the public trust. At the same time, there is a new breed of Bitcoin exchanges emerging that have serious institutional involvement with Wall Street participation, are based in New York, London and other financial centers, which will bring the financial instruments, liquidity and other components that will help stabilize the market and smooth out historic volatility. While what happened with MtGox and their customers is truly awful, Bitcoin and the digital currency industry as a whole will be in a much stronger position with companies like that out of the picture.

If I’m a merchant, why accept Bitcoin?

When you look at the existing electronic payments world that we have today, the processors are taking a meaningful percentage of revenue from every business that accepts electronic payments. So for a business to be able to accept a payment from any user, anywhere in the world, to accept that with much lower fraud risk than they have with existing payment instruments, and to have that settle nearly instantly without a fee, that is very attractive.

A world without interchange fees is appealing, but they are there in part to cover the costs that payment processors bear, including for services like fraud mitigation. Why are the economics more favorable for Bitcoin?

The cryptography-based foundation of risk is really fundamental, so you are able to enable these kinds of transactions without a central clearinghouse or without a central network controller. And therefore there are then dramatically different economies of scale. Anyone can build a global media company today for effectively no cost, because the cost of data transfer is so low. But the businesses who accept payments today are doing it with proprietary networks that aren’t as flexible and dynamic as the open internet. Essentially, with Bitcoin you are cutting costs by using the open internet and open source software that is free to deploy. The combination of those gives you tremendous economic advantage.

Talk a little bit about the cryptography involved, and why you see the technical breakthrough as significant, and as lowering fraud risk.

Let’s use the Target data breach as a use case. Every business you interact with, you give them the keys to your bank account. As a result, we have all this information flying around in an unsecured manner and we have all these security requirements that are put on merchants.

Bitcoin’s public key cryptography model blows that up. In a Bitcoin-based model, your public key is just used as a reference, and you sign the transaction with your private key, so the recipient knows that you who actually signed it.

But someone still needs to protect my bitcoins from being stolen by hackers, correct?

It does require that consumers are storing their money, which is at the end of the day about storing the private keys that sign transactions. To the degree that those are vulnerable to theft, fraud can be committed. A big part of what companies like Circle are focused on is that custodial role, represented in the maintenance of private keys. How do we do that in a way where it’s hyper-secure, so you don’t have to worry about it like the paper wallet under your mattress or the desktop wallet on your Mac? That’s a big big piece of getting this to be mass adoptable.

Are there certain geographies where you see Bitcoin taking off sooner?

We are very much looking at this as a global market, by definition. I think the advanced economies like the US and Western Europe and parts of Asia, just to hit a few, will be actually very good initial markets. Part of that is the sophistication of consumers with smartphones. There are reasons for this to be attractive in emerging markets, without a doubt, and some of those are political, i.e., boy, if I am a consumer in Argentina, I’d rather have a digital asset to store my money that has a liquid market against dollars and euros and other things, versus a currency that is currently debased and experiencing mass inflation. There are reasons why, from a consumer perspective, you might be interested in that, but our launch strategy is not go find weakened economies and sneak in under the nose of government. That’s not a good strategy.

Circle bills itself not just as a Bitcoin company, but as a digital currency company. Why is that?

The genie’s out of the bottle and the fundamental foundation of digital currency is here and will be built upon and grow. So, whether it’s Bitcoin or an evolution in some other form, for the next 20 years we are going to be in this hybrid economy, i.e., a digital/fiat currency economy. The ability to instantly send and receive money anywhere in the world on a person-to-person basis or a person-to-business basis, to have digital transactions that almost instantly settle and are not subject to the same security and fraud risks that we have with things like credit cards, that I think is going to be really attractive to people.

What Google “Glassholes” Reveal About Managing Innovation

As digital devices go, Google Glass is ingeniously provocative. But does it also risk being innovatively insulting, as well? That fear explains why Google is publicly asking its lead users not to behave like “Glassholes”: “Respect others and if they have questions about Glass don’t get snappy….” Google recently posted. “If you’re asked to turn your phone off, turn Glass off as well. Breaking the rules or being rude will not get businesses excited about Glass and will ruin it for other Explorers.”

Of course, people should always be respectful—“Golden Rule” and all that. But a larger global innovation insight here demands top management attention. Innovation increasingly blurs technical and marketing distinctions between “lead users” and “early adopters.” That challenges how organizations need to manage, learn from and even brand their first-generation customer communities. Disruptive innovators and strategic marketers take note: “Breakthrough” innovation depends less on design thinking and user experience than how well your lead users/early adopters “brand” your breakthroughs in the mind of the marketplace.

In other words, managing the behaviors—and misbehaviors—of your innovation’s early adopters/lead user community may determine success far more effectively than managing its initial features and flaws. Google Glass may be a technical tour de force. But if enough “Glassholes” creep people out or provoke privacy fights, then Google has more than a public relations problem.

Lead users/early adopters—not advertising, marketing and/or promotions—dominate the expectations management that potential customers and prospects care most about. Your lead users or early adopters may be technically brilliant. But if they’re socially and/or culturally obtuse, what your innovation gains in possible functionality may be reputationally undermined by perceived insensitivity and obnoxiousness. Diversity may be more important in the lead user/early adopter phase than most organizations truly appreciate.

For example, texting arguably took over a decade to catch on in America because it was originally seen and defined as the province of teenagers. I’ve argued elsewhere that the entire mobile communications industry was lucky that no tragically sensational auto fatalities caused by inappropriate cellphone use invited draconian regulation. If spammers had been more successful, social media services like email and LinkedIn might have been strangled in their networked cribs.

By contrast, I’m fascinated by how the Zipcars, Ubers and Airbnbs took such immaculate care of their lead users/early adopters so as to preserve the scalability of their business models. Similarly, most people I know first come across the simple and brilliant “Square” technology when paying for their taxis via credit card. If it’s simple, cheap and convenient enough for an immigrant taxi driver, maybe I should give it a look…

Of course, the entire open source movement—from Linux to Hadoop—is a testament to how attracting the right developers can quickly transform an innovation ecosystem worldwide.

This ongoing sociotechnical shift requires greater collaborative scrutiny by your top innovators, marketers and support people. If you’re not managing your convergent lead users/early adopters with the same care and alacrity that you’re using with your best customers and most talented employees, you’re setting yourself up for underperformance or outright failure. Indeed, you’re begging to be regulated, legislated or litigated into falling in line.

Your lead users/early adopters are becoming your most important innovation asset. What steps are you taking to minimize the risk they could become a “Glasshole-like” liability?

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers