Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1458

March 6, 2014

Five Questions to Identify Key Stakeholders

Suppose you’re meeting with a group of managers and staff members to determine who your key stakeholders are. (It’s an important task, because with limited resources, your organization or unit can’t do everything for everyone.) People will submit their ideas, and in no time at all you’ll have a large list — and potentially a nightmare. If you don’t focus on the relationships that matter most, management and staff will be running in all directions, not meeting anyone’s needs very well.

So how do you produce a shorter, more coherent list? Answer the following questions about each contender you’ve identified in your brainstorming session. They’ll help you direct your organization’s energy and resources to the right relationships and activities. The questions and examples are drawn from my years of experience working with a large variety of organizations and management teams.

1. Does the stakeholder have a fundamental impact on your organization’s performance? (Required response: yes.)

Example: A manufacturer of trusses and frames for houses decided, on reflection, that a local council wasn’t a key stakeholder. Though the council set regulations that the company had to follow, those rules didn’t have much of an effect on sales or profits the way, for instance, customers did.

2. Can you clearly identify what you want from the stakeholder? (Required response: yes.)

Example: Members of a law firm’s strategic-planning team knew they wanted revenue from clients, productivity and innovation from employees, and continued funding from partners — yet they couldn’t specify what they wanted from the community, so that relationship wasn’t deemed key.

3. Is the relationship dynamic — that is, do you want it to grow? (Required response: yes.)

Example: A company that ran 17 retirement villages had a dynamic, strategic relationship with current and potential residents. It wanted increased occupancy and more fees for services used. The company’s relationship with a university, by contrast, was static and operationally focused. It involved a fixed amount of research funding and co-branding each year. That’s all that was needed. Though the co-branding generated broader awareness and may have indirectly yielded more residents and revenue, the university itself didn’t achieve key stakeholder status.

4. Can you exist without or easily replace the stakeholder? (Required response: no.)

Example: A professional services firm in HR that had taken out a loan initially listed the bank as a stakeholder. But ultimately, that relationship didn’t qualify as key, because the loan could be easily refinanced with another source.

5. Has the stakeholder already been identified through another relationship? (Required response: no.)

Example: A government department involved in planning and infrastructure listed both employees and unions as key stakeholders. But this amounted to double counting: The unions represented employees’ interests, and the organization’s primary relationship was with its employees.

After you’ve applied the above criteria, your list will certainly be shorter, but it may still feel a bit unwieldy. If that’s the case, see if you can combine categories.

Consider this list of stakeholders for a large practice of brain and spine surgeons:

Patients: individuals and families who use the services of the practice

Medical Referrers: general practitioners, other specialists, and emergency departments that send patients to the practice for examination

Third-Party Referrers: insurers and lawyers who send patients to the practice for an independent medical opinion

Hospitals: tertiary facilities that deliver surgical and medical services

Employees: persons other than surgeons who provide their skills to the practice

Surgeons: specialists who perform surgery within the practice

Shareholders: individuals, and related entities, who own the practice

Note that different types of medical referrers are grouped together. That’s because they all evaluate the medical practice with the same set of criteria: surgery success rate, range of treatment options, waiting time until the patient is treated, reputation among medical peers, proximity of practice to operating hospitals, and likely cost to the patient. But the third-party referrers, for instance, rely on different standards: accuracy of medical assessments, lead time before patient evaluation, amount charged for an expert opinion, professionalism of the practice, and compliance with report deadlines. And the patients look at quality of service (empathy, how clearly the options are explained, waiting time at reception), cost of medical service, payment terms, convenience of practice location to them, perceived surgical skill, and cleanliness and comfort of waiting rooms.

By clustering stakeholders according to common needs, you’ll whittle your list down to a more manageable length, increasing the efficiency and impact of your efforts to meet the right groups’ needs.

When Research Should Come with a Warning Label

In his sharp and engaging new book, The News: A User’s Manual, the philosopher Alain de Botton describes the experience of consuming news as if we are woken each morning by a frantic official armed with “a briefcase filled with a bewildering and then in the end tiring range of issues: ‘Five hospitals are predicted to breach their credit limits by the end of the month,’ ‘The central bank is worried about its ability to raise money on the bond markets,’ ‘A Chinese warship has just left the mainland en route for Vietnam’…What are we meant to think? Where should all this go in our minds?”

His answer is that in a news market overflowing with facts, facts by themselves go unsold; they require a story—and that story, he says mischievously, needs some kind of bias on the part of the author, “a pair of lenses that slide over reality and aim to bring it more clearly into focus.” You can see what he means: our capacity to produce data on everything requires packaging; otherwise, it is like finding oneself in a library where all the books have been disassembled into piles of paragraphs, sentences and words. Our consumption of information requires an algorithm of narrative and the perspective of bias in order to produce focus. The problem — the presiding problem of our knowledge economy — is whether we end up focusing on something that’s actually true.

Just how big a problem this is for industry — and for one industry in particular — is illustrated by a recent study, which, ironically, claimed to uncover the kind of bias we don’t want to see when it comes to assessing the validity of data.

The study, which appeared in PLoS Medicine, argues that industry funding has compromised the evidence on sugar. Systematic reviews of studies on sugared beverage consumption and weight gain — which is to say, reviews which try to sum up the state of the evidence — were five times more likely to conclude no relationship than systematic reviews that had no industry funding. As the headline on Forbes.com put it, succinctly, “Big Sugar Tips The Balance Of The Research Scale.”

This is a powerful indictment precisely because we have heard the same kind of story before: when an industry is in trouble, its first recourse will be to manufacture scientific doubt, or to refer to pre-made scientific doubt. Indeed, should this have not crossed your mind, the PLoS authors tie their findings to past behavior by the tobacco and pharmaceutical industries. Narrative, bias, and focus, provide an overwhelming rationale to file the story under “malfeasance” with a note to disregard the legitimacy of any data produced by that industry’s funding.

But only if the PLoS study is itself true.

The fascinating thing about how this information entered the realm of public debate is not just that no one asked this question, but that our system for producing and sharing such knowledge is poorly designed for asking such questions.

Here is the problem with the PLoS study: it cannot answer the question it claims to answer because of the way it was designed. The researchers looked at systematic reviews conducted between 2006 and 2013. But this period saw a significant change in the kind of research done on sugar and weight gain. At the beginning of the period, there were few randomized control trials and a lot of observational studies; at the end, more randomized control trials, which provide much better evidence of cause and effect. The effect sizes for these trials are still quite small, but when added together, there was more, and qualitatively better, evidence associating sugar consumption and increased weight gain the closer one got to 2013. In fact, the four systematic reviews from 2012 onwards all found mostly positive associations; none were funded by industry.

But can an “industry-funded” systematic review be called “biased” based on studies that didn’t exist when the review was originally carried out? Can a review in 2007 be criticized as biased for not including a study published in 2012?

Now, you might find it odd that this was ever an open debate. Surely we all know as a basic fact that sugar causes weight gain. This is why it is important to remember that the scientific question is not simple weight gain, but whether calorie for calorie sugar causes extra weight gain or whether the specific reduction or elimination of, say, soda, in a diet would lead to weight loss. As the expert panel commissioned to come up with the 2010 dietary guidelines for the US Department of Agriculture noted, the scientific evidence for something you would think would be critical to our understanding of obesity, was “disappointing.”

The PLoS researchers also did not include three reviews, two from 2006 and one from 2007 that did not find an association between sugared beverage consumption and weight and were not funded by industry. They had been included in at least one other systematic analysis of the systematic review literature. While including them doesn’t obviate the temporal flaw in the study’s design, they do show that more academics without industry funding found no effect when asking the same question of the evidence.

Moreover, the PLoS study design (conflict with industry? Yes/no; positive association? Yes/no) also suppresses the fact that the conclusions of systematic review can be mixed, with the authors of one review noting that there is suggestive evidence for a relationship between sugared beverage consumption and those who are overweight, and that such findings should be examined with more randomized control trials. This particular review is labeled as having a conflict with industry not because it was industry funded (it was funded by the National Institutes of Health) but because the authors had past industry funding from the food industry.

This may seem like nit picking. It’s not. But how many people would spot any of this? It certainly didn’t catch the eye of Forbes contributor Larry Huston, who’s an uncommonly good science writer, but then why would it? Why would he be familiar with the systematic review literature on this topic and the evolution of research on sugar and weight gain? (I only know about it because I spent months looking at the academic literature on soda and food taxes and got sucked into the methodological problems hounding the entire field of nutrition.) The New York Times also reported the study without any analysis.

In fact, the people who would immediately know why the PLoS study is misleading are relatively few. Most would not have access to or even an interest in engaging the media, while many would be from industry, the very people the PLoS study effectively warns you not to trust.

But what about peer review? If the past few years have taught us anything, it is that academic publishing is what the Internet was once called — the Wild West. Consider only the complaints aired by a National Institutes of Health workshop, which convened to deal with the problem of why so many findings from animal studies could not be replicated. There was, as the concluding paper, published in Nature said, “broad agreement” that “poor reporting, often associated with poor experimental design, is a significant issue across the life sciences…” In other words, the vices popularly associated with industry-funded studies — a lack of transparency in data, methods, and analysis leading to exaggerated results — were widely prevalent among those funded by government.

Stanford University’s John Ioannidis, who has become a figurehead for a growing movement to improve scientific rigor, warned last November that the state of nutrition research was bedeviled by small sample sizes, weak study design, and poor survey methods. “Almost every single nutrient,” he wrote, “has peer reviewed publications associating it with almost any outcome. . . . Many findings are entirely implausible.”

Even something as fundamental to nutrition research as how much food people consume, which the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey attempts to find out by questionnaire, was shown last year to be wildly inaccurate. Two-thirds of men, and almost 60 percent of women reported consuming less food than was physiologically plausible.

Peer review is valuable, but it is not a guarantor of reliable knowledge. And while the editor of PLoS Medicine defends the paper in a preface by arguing that industry has particular reasons to be biased (“increased sales of their products”) but that academic researchers don’t (because they are engaged in “the honest pursuit of knowledge”), the distinction has become meaningless in the face of publish or perish academic pressures, publication bias toward positive findings, and the growing awareness that poor statistical methods and weak experimental design undermine so much academic research in medicine and health.

Consider the finding published in Significance, the journal of the Royal Statistical Society, in which Stanley Young of the National Institute of Statistical Sciences tested 52 claims (about the effects of vitamins) from 12 observational studies against the results from randomized control trials. Not one observational finding could be replicated.

Imagine a product with a 100 percent failure rate. Or an airline in which the majority of flights crashed. This, we are reminded, is the nature of scientific inquiry: the path to truth is littered with false positives and null results. But we consume information just like any other product; we take flight on the reliability of data. And if there is no risk to taking risks with that data, from hyping research results to burying statistical data where the sun doesn’t shine, then — as we saw in the world of finance and mortgage backed securities — scientists will take risks, and news organizations will eagerly report their findings. The key difference between academic and industry produced data is that we currently treat the second skeptically. That asymmetry is the flaw in our knowledge economy; it leads to moral hazard — and worse.

The PLoS findings may well be used to delegitimize legitimate scientific perspectives in future debates over sugared drinks and food in general. A cohort of scientists has been impugned, and a younger cohort warned that such is their fate if they work for industry. Like a malign butterfly flapping its wings furiously, the storm damage that a biased finding can do in a dynamic system of knowledge is considerable. And repairing it with the truth is very, very difficult.

In a Middle-School Study, Broadband Access Hurt Students’ Grades

The advent of broadband access in middle schools in Portugal led to a decline of 0.78 of a standard deviation in academic grades between 2005 and 2009, say Rodrigo Belo, Pedro Ferreira, and Rahul Telang of Carnegie Mellon University. The reasons are unclear; perhaps broadband access offers students greater distractions. The researchers say they found some evidence that internet use has a significantly greater adverse impact in schools that allow access to YouTube.

The CEO of Kimberly-Clark on Building a Sustainable Company

Companies across the globe are tackling some of the world’s greatest societal challenges — water scarcity, climate change, and even the rights of women and girls in the developing world. Tom Falk, the CEO of Kimberly-Clark Corporation since 2002, talks about how the paper company is taking on environmental issues and has been practicing sustainability for 140 years.

Did you ever have a moment where you said to yourself, “We as a company can be part of the solution to environmental problems”?

FALK: In 1996, I picked up responsibility for our Energy & Environment group. We had already made a lot of progress in reducing energy consumption and water usage, improving forestry policies, and limiting air and water emissions, but my predecessor thought we should set some stretch goals for 2000. Because of our merger with Scott, we were a much larger company and the year 2000 was coming fast. It was a great time to lay out a bigger vision in this area and rally our teams around it. This was the first time we really put something down on paper.

I also remember a meeting several years later with Mike Duke, who was then head of Wal-Mart’s international business. I shared our goals for 2005 with him. Mike impressed upon me how much our performance and reputation in sustainability mattered to Wal-Mart and was fully supportive of our efforts. When our largest customer expressed that level of interest and backing, it underscored for me the importance of our sustainability efforts.

How is your company integrating sustainability into how you do business every day?

Every five years we increase the robustness of our goals, further stretching them. We’ve made excellent progress but we still have work to do. For example, we used to think setting a good example was enough but now we know we need to be more explicit about what we expect from suppliers. We require all of our suppliers to abide by the social compliance standards that we set.

Where in your company do ideas for sustainability initiatives start?

Some of the best thinking on how to meet our goals have come from employees in our mills. We first introduced Neve Compacto, a low-energy paper product, in Italy, to help retailers save shelf space and moms save room in their storage closet. Our Brazilian team saw how well it was working there and adapted it for use in their market. It’s been a huge success there. The Compacto rolls reduce the average amount of packaging used by 13%, which is equivalent to just over 1.8 million empty plastic water bottles in one year.

If the ultimate goal is to create both economic value and social value, how do you strike the right balance? Are you willing to take an economic loss of some kind if the social return is unmatched?

This is the tough question in sustainability. We face trade-offs in every area of our business. We never say, “Let’s not spend the money to improve the safety of our machines because it’s cheaper to let employees get injured.” So, yes, we make investments today that have a future payoff and like any investment choice, we consider the risk and benefits to our company and to the world around us.

We believe that sustainability and corporate social responsibility create value for Kimberly-Clark, whether it’s direct value, like cost savings or risk avoidance, or indirect value, like enhanced reputation or the ability to recruit and retain top talent.

How do you decide which investments to make?

We use the following criteria:

We put our employees and the communities in which we do business first.

We support legitimate social and environmental issues that are globally relevant but also have a clear fit with our brands and business strategies.

We look for a connection to the business objectives for the target market.

The benefit must be measureable—we can clearly track the impact on our business and our ability to improve lives.

How much of your company’s move in this direction is consumer-driven vs. conscience-driven?

As a paper company, established 140 years ago, we started off practicing sustainable forestry: When we cut one tree down, we needed to plant two so we would always have the resource to support our business. It’s only been in the last 10 years or so that the term “sustainability” has come in to common usage. For the 130 years before that, Kimberly-Clark was just doing the right thing.

Sure, consumer interest in sustainable products is increasing in various markets around the world. However, the vast majority of consumers won’t trade off product performance or cost for a more sustainable solution. Our challenge as brand-builders and manufacturers is to develop products and solutions that are better for the environment and don’t force moms to make a trade off.

Customers, consumers, employees, investors, suppliers and communities all now expect more from corporations. Great companies will live up to these expectations and win in the marketplace.

This is part of an ongoing series from Harvard Business Review and the Skoll World Forum on how mega-corporations are integrating innovative ways to solve social and environmental problems into their core operations.

March 5, 2014

Is Ukraine a Prize Only Russia Wants to Win?

Russia versus the West is more than a mismatch. From an economic perspective, Russia’s economy is only about an eighth the size of America’s, and also an eighth the size of the EU’s. Taking on a group of adversaries that together are 16 times richer than you is hardly a wise gamble. But Russian President Putin is taking it.

Why does he think he can challenge the Europe and the U.S. on Ukraine and apparently win?

OK, there’s energy at stake. We’ve all heard that Europe is dependent on Russian for natural gas and oil. But is it really? And when is dependency a two-way street? Russia supplies Europe with about a third of its fuel. Looked at from the other side, Europe buys about 70 percent of Russia’s energy. One would think a customer that buys 70 percent of what you make is a pretty important customer. That’s especially true when that customer’s purchases account for 20 percent or so of your GDP, and nearly all of your governmental expenditures. So who exactly is dependent on whom?

Cut the energy pipeline between Russia and Europe and Europe’s massive economy will no doubt slow, perhaps precipitously. But Europe will be able to replace its imports of oil and natural gas a lot faster than Russia replaces the money it earns selling to Europe. The U.S., which recently surpassed Russia as the world’s largest energy producer, can provide Europe with oil and perhaps some natural gas. Norway can provide natural gas, and so can Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. If Russia stopped selling energy to the EU, the continent would stumble, but Russia would surely fall.

Here’s another angle on the mismatch: the countries’ sizes. Russia has 143 million people living within its borders while the EU has 500 million and the US has 310 million, meaning Russia is outnumbered again. And what if Russia did take the Ukraine – all of it? That would add 45 million people to the Russian side, but it would also add roughly $20 billion in external debt.

Then there’s the military mismatch. Russia has fewer soldiers than the U.S. military, and many fewer than NATO. And, whereas the U.S. spends roughly $650 billion a year on its fighting forces, Russia spends just $90 billion, a fraction of that amount.

So how can a country like Russia, which is so much smaller than the West on every measure, challenge Europe and the U.S. on Ukraine and apparently win? Is it fatigue on the part of the West? Fear of fighting? Is it choosing prudence over risk?

Or is Ukraine a prize no one but Russia really wants to win?

Editor’s note: Explore the economic connections between Ukraine, Russia, and Europe for yourself with these interactive graphics.

Why Work Is Lonely

There is an old cartoon I often show to the managers I work with. It portrays a smiling executive team around a long table. The chairman is asking, “All in favor?” Everyone’s hand is up. Meanwhile, the cloud hovering above each head contains a dissonant view: “You’ve got to be kidding;” “Heaven forbid;” “Perish the thought.” It never fails to provoke awkward laughter of self-recognition.

I have a name for this cocktail of deference, conformity and passive aggression that chokes people and teams. I call it violent politeness.

I have witnessed it countless times. After some discussion, often labeled “brainstorming,” a group will go along with the most innocuous suggestion and follow it halfheartedly, keeping itself busy to avoid admitting what everyone knows: it is not going to work.

When I probe junior managers about this dynamic, they usually explain that their caution reflects their uncertain status. It feels too risky to raise misgivings, especially if one cannot offer an alternative course of action. It might make them look clueless or disruptive to their boss or colleagues.

Early in my career, I was sympathetic to that analysis. I knew it all too well, the fear of being myself at work—or more precisely, the uncertainty about which self to be.

I thought, and advised reassuringly, that things would improve with time. As young managers became established, they would have more latitude to put their mark on the roles they took—and so would I. It would be easier to find and speak with our own voice.

It took me a few years to realize that I was offering a wishful lie. Time does not summon courage. It only morphs the fear of speaking truth to power into the fear of speaking truth in power. Once I began working with senior executives, I found those hesitations all still there, only stronger in the face of increased visibility and pressure.

Owning one’s defiance feels risky at every (st)age. Speaking up feels even more exposing and consequential, spontaneity more unfamiliar, when we’ve spent much of our careers learning to modulate our silence—and being rewarded for it.

This is why violent politeness often gets stronger the closer one gets to the C-suite. In too many organizations, in too many of our minds, it is still what gets you there.

It is different from “groupthink.” It is not always borne of convenience, cowardice and backside-covering—or evidence of a lack of commitment or malicious intent.

As a personal habit, we often justify it with the wish not to embarrass others or to appear supportive. As a group norm, we reinforce it by endorsing “constructive” cultures that denigrate dissent as a lesser form of participation than enthusiasm.

Violent politeness is such an ingrained custom that we keep making excuses.

We keep forgetting that our closest relationships are not those where tension is glossed over but those where it can be aired and worked through safely enough.

We keep telling ourselves that speaking up is costly and ignoring the price of silence. Perhaps because the price of speaking up—being ignored, judged, labeled a poor team player or worse—is paid immediately and by those who speak first. The price of silence, on the other hand, is exacted later and paid by the group—when the bubble of false harmony bursts, relationships crumble or projects fail.

We keep ignoring that by censoring ourselves in order not to appear vulnerable, we are often complicit in being misunderstood. Silence is easy to fill with suspicions and assumptions about what others do not know about us.

We keep fooling ourselves that we need to wait and time will make us more open, as if time alone did anything more than harden tentativeness into superficiality. And in the meantime, violent politeness corrodes collaboration, problem solving and decision-making. It kills enthusiasm and drags learning to a halt.

We cast it carelessly, this stone that kills two birds we claim to cherish—our voice and our relationships. And when we have done it long enough that we have lost hope to speak or hear the truth, to truly care and be cared for, we tell ourselves…

It’s lonely at the top.

Of course it is, and not just there. It’s lonely everywhere you feel that you must give up your voice to stay in the room. It’s lonely everywhere relationships are brittle.

Violent politeness is tied to loneliness in a vicious cycle. Once you tolerate the former you worsen the latter, and vice versa. Neither is a property of “the top,” a necessary evil, or, worse, a badge of honor.

They are choices.

They are choices to keep commitments often made unconsciously, early on and far from any top. Commitments to look strong, caring, and in control. Commitments to keep our groups looking harmonious. Commitments we care so much about keeping that we are prepared to sacrifice learning, effectiveness, freedom, and intimacy.

It is to honor these commitments that we betray ourselves as much as others.

When I show that cartoon, most managers readily recognize themselves in the self-censoring team members pretending to agree. Few identify first with the meeting’s chairperson. No wonder. When I ask them to do so and guess how they would feel, the laughter usually stops.

Lonely, is the most common answer. Burdened, blinded, mistrusted, clueless, are frequent answers too.

Violent politeness keeps leaders stuck in the very place we say we least want leaders to be—carrying the glory if things go well and the blame if they don’t. Stressed out, alone, and handsomely rewarded for it.

Some argue that we unconsciously like it that way. Because applauding or rejecting leaders feels easier than sharing the burden of leading. Because isolation feels safer than admitting doubt or asking for help. Because at one time or other we have all been hurt by leaders who ignored us or took our dissent as an attack and retaliated.

All that may be true. But most of all we do it to keep bolstering airbrushed images of leadership and teamwork—at the expense of the messier work both take.

We can’t break violent politeness or end loneliness at the top, or anywhere else, until we are ready to sacrifice those idealized images and stop hiding in plain view. It is a tiny step that takes a lot of courage. The courage to take our work seriously and ourselves less so. The courage to be both vulnerable and generous—and to stop outsourcing shame to those who can’t afford to hide.

‘The top,’ in that way, is no different than anywhere else. We need good friends to thrive and be ourselves. Real friends, that is. The kind who would rather be ruthlessly honest than violently polite.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Meet the Fastest Rising Executive in the Fortune 100

If President Obama Can Get Home for Dinner, Why Can’t You?

To Get Honest Feedback, Leaders Need to Ask

Don’t End Your Career With Regrets in Your Personal Life

March 4, 2014

Visualizing the Economic Ties Between Russia, Ukraine, and Europe

As the situation between Ukraine and Russia continues to unfold, Europe and the U.S. are mulling what effect economic sanctions may have — not only on Russia, but on their own vulnerable economies. This economic interdependence is particularly apparent with respect to energy, and can be visualized by the The Observatory of Economic Complexity, from the MIT Media Lab Macro Connections group, which charts the flow of imports and exports around the world. Here, for instance, are the nations Russia exports to (the data displayed below is from 2011, but the charts are interactive — so play around with them to explore more data):

A significant share of Russian exports end up in Europe, and a large share of Russian imports come from Europe. But while Europe is hence clearly very important to Russia, the flip side is that Russia is much a smaller player from Europe’s point of view. For instance, only 3.2% of German exports end up in Russia, and only 4% of German imports hail from there. The figures for the U.K. and France, Europe’s other two largest economies, are even smaller, under 2% in some cases. It would be tempting to conclude that Russia, then, has more to lose from economic isolation.

But of course, it’s not that straightforward. Complicating matters (as always seems to be the case in international disputes) is energy; Russia supplies 30% of Europe’s natural gas and is the world’s largest exporter of it, as visualized below:

Then there’s Ukraine. Just as it’s geographically sandwiched between East and West, it’s economically caught in the middle too. This balancing act is easily seen in this visualization of where Ukraine imports from:

Ukraine’s complex relationship with its neighbors goes far beyond trade, of course — the ouster of president Viktor Yanukovych, which in turn sparked the Crimea crisis, was more about his flagrant corruption than any immediate desire of Ukrainians to join the EU. And as the world’s policeman/banker, the United States is now getting involved as well (Russia is canceling Ukraine’s discount on its natural gas, and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry has pledged economic assistance to offset the resulting increase in energy costs).

But in a sense, Ukraine’s economic tug-of-war mirrors the political and cultural balancing act it faces in deciding how to align itself between Russia and Europe. As an economic matter, it cannot give up access to one without needing much more from the other. And with $16 billion in debt due by the end of 2015, the country needs all the revenues it can get.

Why Uber Needs Clearer Pricing

The way a company sets price is an integral component of its brand. Think about your favorite merchants – what associations of price do you have? Do you think of them as premium, middle-of-the-road, or a value player? Just as prices drive brand perceptions, pricing surprises can damage a company’s brand. Remember the uproar when Apple discounted its iPhone from $599 to $399 just 68 days after introduction?

Uber’s biggest challenge today is customers don’t understand – and have not accepted – the role of price in its brand. The fast growing ride share service varies its prices based on demand. Consumers love the regular prices, which typically are significantly lower than the relevant competition (taxis or car services offering sedan, luxury car, or SUV service). The backlash has been over the “surge” fares charged during peak demand periods – which can be as high as eight times the normal price. Uber has done a poor job of “spinning” these surge prices and hasn’t been clear about its pricing strategy.

I’m a pricing consultant and a frequent Uber user, and even I am confused by Uber’s conflicting messages:

Is it a low cost service? In Boston, for instance, its discount uberX service is marketed as being 30% cheaper than taxis. This release completely neglects to mention the real possibility of surge pricing (even going so far as to state “uberX is now an even more cost-effective ride – 24 hours a day”).

Is it a market-maker? In explaining its surge prices, Uber claims it uses higher prices during peak times simply to equate demand with supply. Premiums incent more drivers to provide service.

Does it charge what the market will bear, as most companies do? Uber recently admitted to deliberately restricting supply in San Diego on Valentine’s Day – leading to prolonged surge pricing. Uber explained it wanted drivers (and hence, the company) to earn more money.

This lack of clarity is frustrating customers, resulting in damaging publicity that is threatening growth.

So what should Uber do now?

One solution would be to follow rock musician Kid Rock’s concert ticket pricing strategy.

Last summer, Kid Rock announced a game-changing pricing strategy – all of his concert tickets were priced at $20 except for 1,000 of the best seats in the house. These “platinum seats” ranged in price from $60 – $350. This strategy was a great success and described as an “unbelievable money maker” by concert promoter Live Nation. He played, for instance, before 28,000 fans in Chicago (his previous appearance in the area sold 15,000 tickets). Just as important, this strategy bolstered Kid Rock’s image as a musician who is fair about ticket prices. What a winning trifecta: more profit, higher attendance, and a stronger brand.

What’s most fascinating is fans accepted the premium priced platinum seats. Rock music fans are notoriously sensitive to both high prices (quick to scream, “The man is ripping us off”) as well as the notion that only the well-heeled sit in the best seats (often opining, “True fans should be in the front rows”). Kid Rock was upfront about and did a masterful job of explaining that high priced seats cross-subsidize, thus make possible, $20 tickets for most.

When you think about it, Uber’s regular and surge prices are akin to Kid Rock’s $20 and platinum tickets. Surge pricing is very limited — Uber claims that during Valentine’s Day week, only 5.6 percent of trips were at surge prices. Uber needs to be both vocal and succinct about its value proposition: great service (as a regular rider, I can attest to this) with low prices most of the time. During peak periods, surge prices allow Uber to maintain service standards as well as cross-subsidize lower priced rides. “Cross-subsidize” is more consumer friendly than the cold-hearted economic rationale of “let the market rule.” Uber shouldn’t go into too much detail about the mechanics of surge prices. Explaining a pricing strategy is akin to a legal deposition – the more you explain, the more open you are to criticism. Keep it simple.

This explanation also keeps Uber nimble in case it needs to change its driver strategy. Currently, drivers don’t have a schedule and work whenever they want. This is likely to lead to what economists call “cream skimming” — some drivers will work only when prices are high. An uberX driver recently grumbled to me that it’s demoralizing to hustle for $5 fares. To keep its best drivers and maintain service, Uber may eventually opt to restrict the opportunity to reap high fares during surge price periods to drivers who also work during off-peak times (thus deliberately curb supply). It’s like being a waiter at a restaurant – you work the lousy shifts in order make big money on weekends.

Uber has a great pricing strategy that can truly transform the private car industry. Like most new companies, there’s always room to improve on its initial rollout. Justifying its surge pricing – which has been a public relations nightmare – should be its top priority.

How Much Do Companies Really Worry About Climate Change?

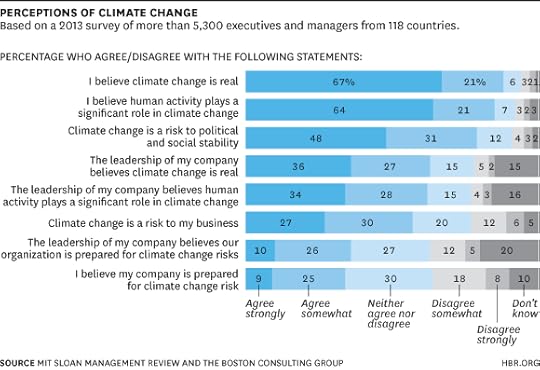

Are managers particularly concerned about the impacts of climate change on their businesses? If we believe the results of a recent MIT Sloan and BCG survey, the answer is no. But it may not be that dire.

First the sobering survey results: Only 27% of respondents agreed strongly that climate change is a risk to their business — which is frightening when you think about what that says about companies’ level of readiness for the significant changes that are upon us already (extreme weather, disruptions to operations and supply chains, and the changing expectations of customers and employees). Additionally, only 11% ranked climate change as a very significant issue.

In a good overview of these survey results published in the MIT Sloan Management Review, editor Nina Kruschwitz voices a legitimate concern that their findings don’t jibe with other reports lately, in particular an article in The New York Times titled, “Industry Awakens to the Threat of Climate Change.” That story focuses on how the World Economic Forum, and some specific companies like Coca-Cola and Nike, are taking the issue seriously.

Although the two stories seem at odds, they may be describing versions of the same reality. Part of the disconnect stems from what’s said by company leaders versus what a broad selection of managers think. A growing number of companies are publicly declaring support for strong climate policy — Apple just signed onto the Climate Declaration, joining Nike and many others. But within the ranks of these leading companies, I’m sure there are wide-ranging views, from supportive to skeptical or even hostile.

But the bigger gap is likely a perception of what “climate change” means to survey respondents. Many may think of the issue narrowly as rising temperatures, or as something their companies should manage only for philanthropic, good-for-the-planet reasons.

What Nike and Coca-Cola leadership get is that the climate issue is a systemic problem, not easily defined in one single way, and it directly and profoundly affects their business. Water availability, for example, is in the process of shifting, sometimes dramatically, which means more water and rains in some areas, and much less in others. Extreme weather brings unpredictable dangers for physical assets or massive disruptions to supply chains (like auto and hard drive companies found out with floods in Thailand in 2011).

Most survey respondents probably miss these systemic issues. And very few would consider the much softer elements of risk and value around climate change — like whether employees and customers believe the company is doing enough on the issue.

Nonetheless, companies’ understanding of climate change is in fact shifting subtly as more understand the problem as one of risk to be managed — not a scientific or political debate about absolute certainty, but a conversation about possible futures. When risk officers and smart business leaders look at climate this way, they can have productive conversations about how to build more resilient enterprises.

So the real issue of concern that the survey uncovers is not a lack of belief in climate change per se, but a gap in readiness for volatility: Only 9% of respondents thought their organizations were really prepared.

On the one hand, there may not be too much to worry about in this finding. The same perception gap about defining climate change may make managers blind to how much their companies are already doing to reduce carbon and energy use, and thus reduce one element of risk — reliance on volatilely priced fuels. A fleet efficiency project, which many would just call good business with a good payback, is a carbon and climate action. So are a lighting retrofit, a boiler overhaul, innovation to reduce energy use of your products, and much more.

That said, the respondents might be right in the larger sense that companies are unprepared for systemic and longer-term challenges. In my experience, most companies are risk-averse and like to fashion themselves as great “fast followers.” But Kruschwitz makes an important point: “Being a fast follower on climate change…may be more complex and require longer lead times than most companies are anticipating.” That’s exactly right. You can’t re-arrange supply chains to avoid droughts or storm risk quickly, or flood-protect or move your facilities on the fly.

Companies are in general bad at thinking long-term and preparing for multiple contingencies (it goes against being lean and maximizing short-term earnings). I believe we need fundamentally new modes of operating that create more resilient enterprises, or what I’m calling “the big pivot” in my forthcoming book.

Companies will, among other things, need to fight the short-termism that plagues business, set goals based on science to drastically cut carbon fast enough, innovate in heretical new ways, and collaborate with friends and enemies alike.

So does it matter much if your company’s managers think about “climate change” as a problem in and of itself? In a sense, no, since there is so much a company can do without everyone agreeing on that issue. But the companies that do get it will be able to set their sights and goals differently, and rally passionate employees to really change how they operate. Those more engaged organizations will be more innovative and have a leg up in a hotter, scarcer world.

Are You Too Afraid to Succeed?

Tim had been on the fast track. An Ivy League graduate, he had joined one of the premier consulting firms as an associate. He went on to take an MBA at INSEAD, graduating at the top of his class. Recruited by a pharmaceutical firm he rose quickly through the ranks, joining the executive team in record time. Within just eight years after joining the company he was appointed its CEO.

That was when things started to fall apart. Colleagues soon noticed that Tim seemed oddly reluctant to take important decisions. He would put off big projects and spend an inordinate amount of time on minor problems. As a result, the company missed out on some big opportunities.

His behavior became increasingly worrisome. He would turn up visibly drunk for important meetings. Although the board cut Tim some slack at first, his shortcomings quickly became too obvious to be to be ignored and within two years of his appointment the board dismissed him.

What went wrong?

Tim came to ask me that very question after he had lost his job. Listening to his story, I realized that its origins stretched back to his childhood. Tim seemed to have unconscious feelings of guilt about his success. I discovered that he was consumed by the idea (crazy as it may sound) that his being too successful would upset his father, who had repeatedly failed in his business endeavors and had become embittered by it.

He had taken out these emotions on Tim, constantly telling him that he (Tim) didn’t have what it took to be successful. As the years went by, Tim had internalized these criticisms. But his debasing sense of self remained dormant until he became CEO. With nowhere further to go, he revealed the inadequacy he had been so anxious to conceal, perversely sabotaging his own career in order to fulfill his belief that he wasn’t up to the top job.

This fear of success is a more common dynamic than you might think. Many years ago, Sigmund Freud tried to explain it in an essay called “Those Wrecked by Success”, published in his 1916 work Some Character Types Met With in Psycho-Analytic Work. He noted that some people become sick when a deeply rooted and long-cherished desire comes to fulfillment. He gave as an example a professor who cherished a wish to succeed his teacher. When eventually the wish came true and the professor succeeded his mentor, depression, feelings of inadequacy, and work inhibition set in. It was as if this professor felt he had not deserved his success in some way and that it was a manifest travesty to step into his mentor’s shoes.

I’ve encountered many high-flying executives like Tim who function extremely well as long as they aren’t in the number-one position. But the moment they’re placed in the spotlight, they are in uncharted territory and can no longer hide behind someone else. As President Truman used to say, “The buck stops here.” CEOs — whoever they are in whatever organization — have to make crucial decisions. They can’t pass the buck to anybody else. In that extremely visible role, they become highly vulnerable. Their effectiveness diminishes as they succumb to self-destructive behaviors. Some of them feel like impostors. Most also fear that the higher they climb, the further they’ll fall when they make a mistake. There’s also the constant worry that rivals will take their success away. As the writer Ambrose Bierce said in The Devil’s Dictionary, “Success is the one unpardonable sin against one’s fellows.”

The first step towards getting over the fear of success is to recognize it. Think back to your childhood. Did a parent, another family member, or a teacher, or a sports coach keep telling you that you weren’t very capable or likeable, or never seem to be satisfied with your work, no matter how well you performed? To overcome his fears, I had to get Tim surface his associations around success. He needed to better understand the sources of his fears and discard his secret self-image as an unsuccessful, undeserving person.

During the coaching process, Tim came to realize how busily he had engaged in self-sabotaging activities that held him back from achieving his goals and dreams—including in his personal life. What he found particularly helpful was being asked questions that challenged his internal narrative of success. For example, how did he envision success? Could he do a “cost-benefit analysis” of what it meant to be successful?

Tim was lucky; he got a second chance at another company. And thanks to his voyage of self-discovery he was able to overcome his fear of success. As boards consider promising executives for promotion it’s probably worthwhile engaging some coaching help to make sure that the young star they have such high hopes for does not get extinguished by some hidden and unjustified sense of unworthiness.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers