Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1454

March 13, 2014

Why Is Ukraine’s Economy Such a Mess?

When Ukraine became an independent nation in 1991, it was on more or less the same economic footing as its neighbors. Look what’s happened since:

I did leave off Moldova, which shares a border with Ukraine and is even poorer. But Moldova is a landlocked little country of 3.5 million. Ukraine has 45 million inhabitants, is the second-largest European country by land area (after the European parts of Russia and not counting the Asian parts of Turkey) and by all rights ought to be one of the continent’s major economic powers.

It isn’t. Instead, Ukraine was deeply in debt and looking for bailouts from West and East when an uprising ousted president Viktor Yanukovych in February, then a Russian invasion of the Crimean peninsula made the country the focus of global political attention. I was curious about the economic roots of this turmoil, so I talked to Chrystia Freeland.

Freeland is a new Liberal Party member of the Canadian Parliament representing downtown Toronto. She also grew up speaking Ukrainian. Her late mother was a child of Ukrainian refugees, born in a displaced-persons camp in Germany right after World War II and raised in Canada, who returned to Ukraine in the early 1990s to help craft the country’s Constitution, among other things. Chrystia Freeland was in Ukraine in those days too, working as a stringer for several Western publications. She went onto a journalism career at the Financial Times, Globe and Mail, and Reuters, and wrote books on Russia’s transition to capitalism and the rise of the global plutocracy. She spent last week in Ukraine, and wrote an essay on the political situation there for last Sunday’s New York Times.

What initially made us think of calling you was that news a week or so ago that the new government in Ukraine was asking a few oligarchs to help out by becoming governors of Eastern provinces. What’s up with that?

I also was really struck by that news. I think the people of Ukraine should have some medium-term concerns about that — one of the reasons that you had this uprising against Yanukovych was because there was too much crony capitalism.

But in the short-term, particularly given the subsequent Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is turning out to be a rather prescient action. What is not fully apparent if you’re outside Ukraine is the extent to which Yanukovych compromised the entire structure of government. State institutions were incredibly compromised, incredibly corrupt. The result was, following the overthrow of Yanukovych, in parts of the country the government just melted away. What the Eastern Ukrainian oligarchs have been able to do because they are very, very wealthy and have their own strong local organizations and contacts, is rebuild some sort of government presence really fast.

The other consequence of putting them in charge of Eastern Ukraine is it shows the extent to which this image of the country as being divided along ethnic lines, of this being a Yugoslav-style ethnocultural conflict, just isn’t true. As it happens, many of these oligarchs are not ethnically Ukrainian.

Who are these oligarchs? We’re familiar with the Russian variety, what’s the same and what’s different about the Ukrainian ones?

In general they’ve made their money in heavy industry, so that’s quite different from most of the Russian oligarchs. That’s why they’re not quite as rich, because there wasn’t quite as much money to be made. There were a lot of Soviet-era machine-bulding plants in Eastern Ukraine, machine-building and metals. There is also some banking, and media interests.

The East has this old industrial base. What does the Ukrainian economy consist of on the whole? Is it heavily agricultural?

The industrial base is important, particularly in eastern Ukraine. We all know about Ukraine as the breadbasket of Europe, and it is indeed an incredibly fertile country. There’s been a lot of Chinese investment in that part of the Ukrainian economy. There is also a technology outsourcing industry. And then finally, in some parts of Ukraine, tourism has been becoming more important.

Why is the economy such a mess?

Because of very bad, kleptocratic governments. That is 90% of the reason. In terms of the economy, Ukraine only accomplished maybe half of the things that you need to do, when the Soviet Union collapsed and they moved to a market economy. They did do privatization. There are now a lot of private companies, and there is a market. It’s important for us to remember that not so long ago even selling a pair of jeans was illegal.

But what they failed to do was build an effective rule of law and government institutions. Corruption, in the Yanukovych era at least, was absolutely rampant. And some important reforms of state finances haven’t happened. In particular, energy prices are still subsidized. Of course, when you move to free-market prices that’s a huge shock to the society. But Ukraine’s failure to liberalize energy prices is part of the reason that it has this great dependency on Russia.

Having said all of that, and having been in Kyiv* last week, I think there’s a bit of an Italian phenomenon going on, where you actually have a highly educated, very entrepreneurial population, but because you had this incredibly corrupt state, a lot of the Ukrainian economy has gone underground. Walking through the streets of many Ukrainian cities — Kyiv, Lviv in Western Ukraine, Dnipropetrovsk in the East — you feel yourself to be in a much more prosperous society than the official data reflect.

The official data is incredible. Poland on the one side and Russia on the other are both in the low twenty-thousands in GDP per capita, and Ukraine is officially at $7,298.

There is no doubt that Ukraine has fared much, much worse than Poland. That is a testament to how important government decisions are. These countries were not so far apart in 1991 when Ukraine became independent, and the Poles by and large have done the right things, and the Ukrainian government has not.

The sense I get is that pretty much every government since independence has had big issues with corruption, but under Yanukovych it went from being this thing that the government did on the side to the entire reason the government existed. Is that fair?

One of the founders of the Maidan movement is this former investigative journalist named Yegor Sobolev. He said what drove him crazy was you couldn’t even call it corruption anymore. It was like a marauding horde. Corruption stopped being something that poorly paid government officials did on the side and became the main reason for the government’s existence.

Radek Sikorski, the Polish foreign minister who has been playing a very good and important role in Ukraine, said that before the Yanukovych regime fell he went into one meeting with Ukrainian officials and they laughed at him for having a regular watch. He said everyone in that room had a wristwatch worth $30,000. That’s the sign of a really corrupt government.

With this new regime do you see potential for Ukraine moving in the right direction?

I think this government has a better chance than any previous Ukrainian government has had. A lot will depend of course on the presidential elections, and then there will be a need for new parliamentary elections. But so far it’s a group of people who understand what they need to do. They’ve seen Central Europe and the Baltic republics walk that path. It’s pretty clear what needs to be done.

What was quite impressive to me was that the government immediately took some steps last week to be more transparent and less entitled. All the ministries had these huge fleets of cars, and they cut them back to just one car per ministry. When Yatsenyuk, the prime minister, traveled to Brussels last week, he demonstratively flew commercial. These are gestures absolutely, but they symbolize something important.

Having said all of that, economic reform, urgent though it is for Ukraine, falls by the wayside when you’re being invaded, and that is the state of the country right now.

* When Freeland said it, it sounded like “Kayiv,” so I went with this spelling instead of the old-fashioned “Kiev.”

The Crisis In Ukraine Shows Why Strategy Is No Longer A Game Of Chess

As the crisis in Ukraine spreads through Crimea—and possibly to Eastern Ukraine as well—it is not conventional measures of power we should be paying attention to. Commentators have expended a lot of ink and pixels on scale — the size of various armies and economies — but are still underplaying the importance of networked power. It’s these connections that really matter.

It is, of course, Russia’s connections to a large segment of the Crimean population that Putin used as a pretext for his invasion. It was also fear of connections (ethnic Ukrainians to the mainland, Crimean Tatars to Turkey), which led him to shut down television stations and other channels of communication.

And it is through deepening and severing connections that the West intends to combat Putin’s aggression, by uniting with Western and Eastern European allies to apply sanctions that will deny the economic and cultural ties that Russians have come to rely on.

Strategy is no longer a game of chess because power no longer depends on nodes, but on networks.

Consider how this crisis started. Until very recently, Viktor Yanukovych held nearly absolute power in Ukraine. When confronted, he remained defiant, exercising every lever of authority he possessed, including his control over the media, political structures and finally, the use of force.

His rivals were almost comically ill-equipped. They donned makeshift shields and helmets, burnt tires to obstruct snipers, and communicated via social media. Yet still, they prevailed through a network of unseen linkages that proved to be decisive.

While Yanukovych was a man of uncommon ineptitude, we’ve seen similar scenes play out in Egypt and Tunisia—which had leaders reknown for their political savvy. Never has it been more obvious that past notions of power are becoming obsolete, and with them, traditional notions of strategy.

The truth is that it’s not the “influentials” that the powerful have to worry about. It’s when normal everyday people start linking themselves to the movement. One of the things that surprised me when I was working in Ukraine during 2004’s Orange Revolution was how many of my colleagues I saw at the Maidan. I noticed the same trend during last year’s protests in Turkey, where I have also lived.

Scenes like these are are exactly what network scientists predict: A small group of passionate people can influence others that are slightly more reticent, still others take notice and also join in.

Make no mistake, the face of revolution today looks a lot more like The Good Wife than it does Homeland. It looks like everyday moms stepping up; not like government spies who have it all figured out.

The 20th century was driven by the power of scale. The path to success was paved by tightly controlling integrated value chains to keep costs low, and the bigger you were, the more power you had.

The 21st century is increasingly driven by semantic linkages, which increases with your number of connections and the strength of your networks.

To wit: soon as Viktor Yanukovych entered office, he moved quickly to take firm hold on all the traditional levers of power. He pushed a new constitution through Parliament that considerably strengthened his office, threw his chief political opponent, Yulia Tymoshenko in prison and took control of important media outlets (including, I’m sorry to say, my former company, which published Ukraine’s leading news magazine).

Yet, as it turned out, none of that did him much good. As political scientist Moisés Naím explains in, The End of Power, overthrows are becoming the rule, rather than the exception. He writes, “Power is easier to get, but harder to use or keep.”

Governments, religions, militaries — and yes, companies — are having to learn to live with diminished advantages to scale. Superior capital, technology, and market share no longer confer the benefits they once did. In fact, they might even blind us to dangers that lurk under the surface.

To understand better how power works today, we need to look beyond the nodes and start thinking in terms of networks. With all of his access to power, it was easy for Yanukovych to dismiss the trouble when it started. With his country’s size and resources, it was easy for Putin to think he could scoop up Crimea without too much backlash.

Yet these seemingly small things are connected to larger ones. It was these unseen connections that proved to be Yanukovych’s downfall, and are giving Putin more headaches than he anticipated.

Leaders who fail to recognize the power of semantic networks of unseen connections, and instead rely on traditional notions of power and influence, are fighting a 20th century battle in a 21st century world. They will find their traditional chess pieces a bit useless.

What’s Holding Women Back in Science and Technology Industries

Virginia Rometty at IBM. Marillyn Hewson at Lockheed Martin. Meg Whitman at HP. Ellen Kullman at DuPont. Marissa Mayer at Yahoo. Phebe Novakovic at General Dynamics. The presence of these women would imply that science, engineering, and technology (SET) industries welcome women.

The fact is, senior female leaders in SET industries are still too few and far between. Even as these women blast open doors and blaze trails, new research (PDF) from the Center for Talent Innovation shows that U.S. women working in SET fields are 45% more likely than their male peers to leave the industry within the year.

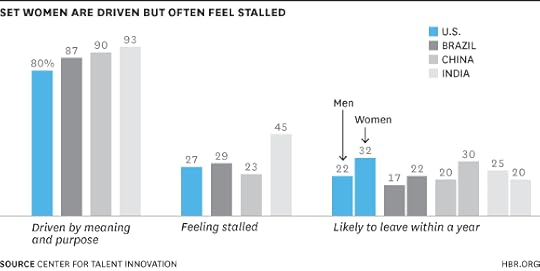

Women in SET in the U.S., Brazil, China, and India are committed to their work and their careers. Over 80% of U.S. women love what they do; in Brazil, China, and India, the numbers are close to 90%. Over three-quarters (76%) of U.S. women consider themselves “very ambitious,” as do 92% of Chinese and 89% of Indian SET women. At the same time, a sizable percentage of SET women feel stalled, with young women feeling particularly frustrated.

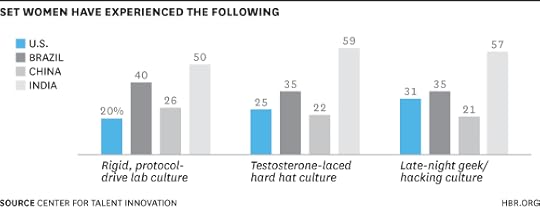

Why are women turning off and tuning out? The study finds that powerful “antigens” (PDF) in SET corporate environments block them from contributing their full potential at work. Gender bias is the common denominator, manifesting in cultures hostile to women: the “lab-coat culture” in science that glorifies extreme hours spent toiling over experiments and penalizes people who need the flexibility to, say, pick up their kids from day care; engineering’s “hard-hat culture” whose pervasive maleness makes women do a “whistle-check” on their work clothes to avoid a barrage of catcalls; and tech’s “geek workplace culture” that women in our study often compared to a super-competitive fraternity of arrogant nerds. These cultures marginalize women, making them feel isolated: 21% of U.S. women in science say they experience “lab-coat cultures”; 25% in engineering face “hard-hat cultures”; and 31% in tech face “geek workplace cultures.”

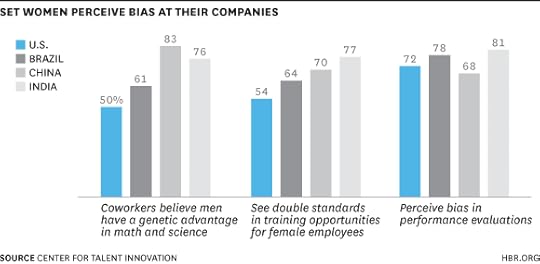

Meanwhile, SET women perceive a double standard in how they are perceived by colleagues and managers. Bias in performance evaluation is systemic: 72% of women in the U.S. and 78% in Brazil perceive bias in their performance evaluations. More than half of U.S. women and more in emerging markets work alongside colleagues who believe men have a genetic advantage in SET fields.

All of these elements sap ambition. Furthermore, a dearth of female role models and effective sponsors leaves many SET women unsure of what it takes to be a leader: 44% of U.S. women and 57% of Chinese women feel that in order to progress they have to behave like a man. “What does it take to be considered leadership material?” asks a former project manager at Microsoft. She glumly concludes, “I think you have to be a man.”

In fact, 46% of U.S. SET women believe senior management more readily sees men as “leadership material.” Stunningly, a sizable percentage of senior leaders agree, with nearly one-third of senior leaders in the U.S. and more than half in China and India believing that a woman would never achieve a top position at their company, no matter how able or high-performing.

The result: Because women don’t look, sound, or act like the alpha male, or because they lack senior-level support, women’s ideas and innovations hit a choke point. SET men are 27% more likely to see their innovative idea make it to market than women (PDF). Unable to contribute their full innovative potential, it’s not surprising that so many SET women have one foot out the door.

There are, however, promising levers for change. The most obvious solution: sponsorship. Sponsors help their protégés crack the unwritten code of executive presence, improving their chances of being perceived as leadership material. Most important to the companies employing them, sponsors help women get their ideas heard — one of the best ways to engender respect and open opportunities to promotion.

We’ve discussed the power of sponsorship in previous posts. It’s especially necessary in SET, where the misogynistic antigens are even more deeply rooted and concentrated than in other fields, making it difficult for some leaders to imagine women holding positions that for decades were dominated by white men. “A sponsor can break down the unspoken biases by advocating for someone in a nontraditional role or offering a different perspective,” explains Christopher Corsico, Boehringer Ingelheim’s global head of Medicine and QRPE.

However, the difficulties women encounter in finding a sponsor in other fields are magnified in SET. Sponsors tend to help people who remind them of themselves. However, senior SET leaders are overwhelmingly white males, making it that much harder for female scientists, engineers, and technologists to trigger that instinctive outreach. The SET fields are also made up of extraordinarily tight-knit networks — of graduates from a particular academic institution, of veterans of a famous project, or of colleagues from a specific lab. Not belonging to the right network makes it much harder to benefit from the close connections that spawn sponsorship. Furthermore, SET women overwhelmingly confuse supporters — mentors and role models — with sponsors. Consequently, they target the wrong people: people they like, rather than leaders with the power to get them where they want to go.

The demand for SET talent is intensifying: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that SET jobs will increase by 17% between 2008 and 2018, a growth rate nearly twice that of non-SET employment. Meanwhile, demand far outstrips supply: Tech leaders like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple will need to fill more than 650,000 new jobs (PDF) by 2018 to meet their growth projections, and two-thirds of those new hires will be for SET roles. Other SET fields are also massively undersupplied: There were six health care openings for every qualified graduate and four for every engineering degree. And this is just in the United States. The situation is multiplied in Brazil, China, and India, where SET industries are the dynamos propelling these economies.

Given the global scramble for SET talent, companies simply cannot afford a drain, much less a hemorrhage, of capable women.

Should You Automate Your Life So that You Can Work Harder?

Would you pay someone in the Philippines to answer your email for you — even your personal messages? Or hire strangers on the internet to plan your spouse’s big birthday party? Or throw meat, vegetables, and butter into a blender and call it dinner?

These are just some of the actual “life-automating” techniques of busy entrepreneurs today.

Consider the case of Maneesh Sethi. Perhaps best known as the easily-distracted man who paid a woman to slap him in the face every time he checked Facebook, he is now working on a product that will let your Facebook friends zap you, via a wearable device not unlike a shock collar, if you don’t follow through on self-appointed goals. He spoke at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas about how he’s now hired a man in Manila (Caleb) to check his email for him. Caleb, who Sethi found through Staff.com, goes through Sethi’s email — both work and personal — every morning and flags important messages for follow-up, as well as categorizing and drafting responses for the rest. By the time Sethi wakes up, his email has already been sorted; and by the end of the day, every message has been answered. And Sethi never had to write a single response himself.

Sethi was on a panel called “Life Automation for Entrepreneurs” that also included podcaster Veronica Belmont, a Getting Things Done devotee. She uses productivity apps (like TripIt and Things) and virtual assistants (such as Fancy Hands) to stay organized and efficient. For instance, she hired temporary assistants on Fancy Hands to plan her husband’s recent birthday party. These “virtual assistants” brainstormed themes; found a venue; planned the party; even devised thoughtful extras she said she’d never have come up with. “I thought I’d never need to outsource these kinds of actions,” she explained, “But frankly, none of us have the time we need.”

And yet perhaps the most radical life automator is Dave Asprey, whose website describes him as “a Silicon Valley investor and technology entrepreneur who spent 15 years and over $300,000 to hack his own biology.” He lost a hundred pounds and raised his IQ 20 points, among other achievements, and now runs a coaching firm called The Bulletproof Executive. His life-automating secret? “I have one API… and her name is Nikki.” Yep, that’s right: an old-fashioned personal assistant. And despite all the time she saves him, he’s the one who advocates blending your dinner so that “you can drink it while you’re doing something else.”

That might not sound healthy, but these workaholics were quick to point out that they don’t sacrifice their health for their work — because then, of course, they couldn’t work. All three entrepreneurs scheduled regular time for exercise and doctor’s visits, even the occasional massage. Belmont acknowledged that “this sounds like a luxury.” But, she argues, “If you don’t take time to take care of yourself, you will not function at the level you need to.” Asprey puts it more bluntly: “you need to take care of your meat.” (And he’s not talking about the kind that goes in the blender.)

We’re guilty of the same ROI-maximizing impulses at HBR, I readily admit — most of what we’ve published on getting enough sleep and exercise, and maintaining reasonable hours, has focused on the bottom-line benefits: greater creativity, fewer mistakes, improved communication and delegation, and so on. And yet I find myself a bit disturbed when this approach is taken to its logical extreme, where everything — taking a walk, even having kids — becomes justifiable by virtue of increasing one’s economic output. We’re meant to be homo sapiens, not homo economicus.

The result of this extreme devotion to work is that we overwhelm ourselves, to the point where even the most trivial decisions become a source of stress. “Even small decisions like replying to an email or forwarding an email or returning a phone call, each of those stresses you out a little bit and wears you down,” argued Sethi. Asprey agreed: “There’s a stress for 40 different apps, choosing which one to use.” To a degree, they’re correct. Decisions do cause stress, and willpower does decline if you overtax it (this is why habits are so powerful — because they move important tasks out of the realm of conscious effort). And in truth, being a high-functioning executive has often required more than just a personal assistant to manage the complexity of work — it’s often also required a spouse who doesn’t work to manage the complexity of life.

But while I acknowledge that the pressure — both external and internal — to devote everything to work is real, I also think it’s vital to resist it. Isn’t making decisions (and dentist appointments) just part of being an adult? Part of living? As Sethi reminded the crowd, “The word decision literally means ‘to cut off.’” While there is something freeing about delegating your decisions to others — dropping those stressors like a hot-air balloon releasing its sandbags — if we pare back too far, we may find that we’re the ones who’ve gotten cut off.

We’ve all got different ideas about what’s reasonable. I think drinking a meat smoothie is a sign of the impending end of civilization, but I’m totally fine with wearing the same thing every day — a la Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, or Barack Obama — in order to save time. And we’ve all got a different appetite for work, a different sense of where to draw the line. However, as James Allworth pointed out in our own SXSW panel on why men work so many hours, it’s tough to stick to those limits when the rewards of work are immediate, and the rewards of life accrue more slowly. (To some parents of teenagers, these rewards may seem practically glacial.) It becomes tempting to reserve the best of ourselves for the short-term gains of work and “automate” the long game of life.

Still, I do think each of us has a Rubicon — wherever it is, and whenever we find it. On crossing it, we may start to see luxury not as having a personal assistant or a weekly massage, but as doing something useless simply because we felt like doing it — not because it made us smarter, or thinner, or more productive.

So the next time your instincts are telling you to press on, to climb higher, to put one more piece of your life on autopilot, consider: even Sisyphus got to walk downhill half the time.

How to Deal with Unfamiliar Situations

Have you recently switched jobs or positions and wondered “What’s going on here?” Have you been given a new task or a new technology that’s completely unfamiliar? Are you working with people who come from different backgrounds and not really sure if you’re all on the same page? Dealing with unfamiliar situations and people is challenging, of course, because we don’t yet have everything figured out. Over time, we adjust. But how can we get better at dealing with the new and unfamiliar—from the start?

Brain science tells us a lot about the answer to this question. The biological challenge is that we are wired to recognize and process familiar people and situations from a young age. For example, children “know” when a face is their own race versus a different one at a very early stage because their brains are wired to detect this. In addition, the brain of a mother is wired to respond specifically to the familiarity of her own infant as compared to that of another. In fact, for all adults it takes only 200 milliseconds to register whether a face is familiar or not and recent research shows us that we process familiar faces with almost double the efficiency than unfamiliar faces. Furthermore, the brain treats “threat” in the same way if you or someone familiar to you is threatened, but responds differently if the person who is threatened is unfamiliar. These differences apply not just to unfamiliar people, but to unfamiliar processes as well. Thus, when someone or something is unfamiliar, the brain is less engaged and empathic and has to use greater effort as well. This is clearly an advantage when it comes to protecting one’s “own” or responding with speed in familiar situations, but what can we do when the people around us or situations in which we find ourselves are constantly changing and unfamiliar as in the current business environment?

First, building up trust and focusing specifically on steps related to this can override the discomfort of unfamiliarity. How do we know this? A recent study demonstrated that when men are given oxytocin—a “trust” hormone—unfamiliar female faces will appear to be more attractive because the trust that oxytocin creates activates the brain’s reward center and overrides the anxiety of unfamiliarity. Many other studies have also shown that oxytocin does in fact enhance trust, possibly because it enhances the distinction between self and other and increases the positive evaluation of others. Thus, trust actually changes how the brain perceives other people.

This implies that when a person or situation is unfamiliar, setting up structures and processes that enhance trust will increase engagement. What are some of these things? Clear communication, being on time, delivering on promises, and fulfilling contractual obligations are good ways to create a climate of trust when things are unfamiliar. And speaking of contracts, in today’s more casual business environment, you may be more inclined to ignore the contractual elements of a business relationship, or even overlook a mutual non-disclosure agreement. It is probably best not to do this for the obvious reasons—and you miss an opportunity to build trust.

Second, stress also plays a role in how we handle unfamiliar situations or people. Stress makes the brain less “friendly” toward novelty—we tend to want what we’re used to even more rather than having to deal with something new when we’re stressed. If you have just entered an unfamiliar situation or find things changing all the time, be aware that your brain will try to slam on the brakes and make a U-turn to old ways of doing things. Hence it is critical that when we are in unfamiliar situations, we must check in with ourselves to deliberately reduce our stress levels. If not, we will be prone to making habitual decisions that were relevant to the past and not the present or future. This has been recognized as a particular vulnerability of leaders, even good ones and is a bias we may completely ignore.

Finally, on a different note, a recent study revealed that when we’ re moved by art, even when it is unfamiliar, it activates brain networks associated with the self. That is, art evokes an emotional experience that connects us with ourselves despite being unfamiliar. We may be moved by intangible elements of the art that connect with corresponding intangible aspects of ourselves. This overrides the otherwise unfamiliar art and make us feel known. Thus, when you find yourself in a culturally unfamiliar environment, look for shared subjective characteristics rather than differences only. As a start, you could connect on vision, mission or intent in a way that expresses your subjective intention and voice, which will help to transcend any existing differences in how you look or behave. Also, elevating a relationship to an art form by producing beautiful and not just timely work will enhance resonance and connection when you are unfamiliar.

Unfamiliar situations can cause a brain-jam if we do not approach them with a conscious sense of how to be. Building up structures that enhance trust, decrease stress and creating an emotional connection with people or a project can help the brain navigate its way to your goals.

The Flawed Premise Behind the Candy Crush IPO

As you may know, King Digital, the company behind the blockbuster game Candy Crush Saga, is about to IPO. The company is seeking a valuation of up to $7.6 billion.

Let me put that in the style it deserves: seven-point-six billion dollars!

I’m not the only one using boldface italics and exclamation points. Jim Surowiecki in the New Yorker and Felix Salmon at Reuters (and many, many others) have analyzed the IPO. The Surowiecki / Salmon consensus is basically, as summarized by my colleague Walt Frick, It’s irrational for the market to value a company that produced a fluke hit so high, but it’s totally rational for the CEO to selfishly want to go public, since the market is valuing them so much higher than they’re actually worth. Surowiecki thinks that the cost of the capital will be too high; the company will actually have to deliver on its promise, and delivering on promises to shareholders is a pain in the neck. Salmon thinks that the market is so frothy that companies have to have a credible plan to IPO just to seem viable as an acquisition.

That’s all well and good, but let’s try to assess King Digital’s core claim: that they have a system for producing addictive games. If you believe that claim, then, given the size of the market for mobile games, you might be willing to pay $21 to $24 per share for a piece of the magic. Of if you’re a tech company looking to own that magic formula, you might be willing to acquire the whole company the day before the IPO for around the market valuation.

So, do they have a magic formula? Let’s start with their one hit game, Candy Crush. It is in fact really well designed around all of the principles of gamification. As this article in Time summarizes: it makes you wait, it provides positive rewards, you can play with one hand, paying is optional but easy, it’s social and nostalgic and escapist, and there’s always more. Fair enough. I’ve spent lots of hours playing the game. So have my wife and daughter and countless others. (If you haven’t played or seen it, go ahead an download the app. I’ll wait a couple of months for you to come back.)

But is this a magic formula? Maybe. But it’s definitely not a secret magic formula. These are well-known principles behind game design and have been used successfully before (e.g., Zynga’s FarmVille for a recent example). Raph Koster published a book illuminating the principles over ten years ago.

And what if it were a secret magic formula? Would that be enough? Probably not. The formula is necessary to have a hit — but not sufficient.

That assessment is based on the work of some Columbia University sociologists, including Matt Salganik. In his interview with HBR, Salganik explained that having a cultural product of good quality is not enough. It’s social processes that makes one good product take off rather than some other equally good (or even better) product.

Salganik and colleagues ran a series of experiments to see how hit songs take off (see the interview for details), but their findings are equally applicable to any cultural product: books, TV shows, and, yes, mobile games. As Salganik said:

Higher quality songs, as a group, will outperform the lower quality ones, but which high-quality song is going to break out is impossible to figure out beforehand. In the experiment, we rewound the world and saw the range of possible outcomes that could have happened – and they’re all over the place!

That is, you cannot predict blockbusters. And that includes the Harry Potter books, the Mona Lisa, “Gangnam Style,” and, yes, Candy Crush.

Having the magic formula for producing addictive games is a necessary component for success (cf. Flappy Bird), but by itself it’s not sufficient, not when there are going to be other games out there that are just as well designed. One way that King Digital could still win is if they could flood the market with games that are all well designed in the same way Candy Crush is. To date, this has not been their strategy.

King Digital is hoping the market will overlook these complications, and perhaps it will. But over time, the problems with a strategy that seeks to produce cultural hits based on a well known formula is bound to run into trouble.

Online Security as Herd Immunity

Online security is only successful if every company does its part.

That was the message of Edward Snowden’s keynote conversation at the SXSW Interactive conference this week, conducted via (highly protected) video link. I was one of the thousands of tech professionals who made up the audience for his first live video appearance, which focused on the need for stronger security practices in the face of government surveillance. “We rely on the ability to trust our communications,” Snowden argued. “Without that we don’t have anything. Our economy cannot succeed.”

I’ve done some pro-vaccination work in my professional life, and Snowden’s exhortation reminded me of nothing so much as the argument for vaccination. That’s because like the effectiveness of online security as Snowden described it, the effectiveness of vaccination depends on herd immunity: as long as enough of the community is vaccinated, diseases like measles and rubella are unheard of. But herd immunity only works if everybody does their part: if too many people depend on their neighbors’ vaccination rather than vaccinating themselves, we get disease outbreaks instead of a healthy community.

Just as all members of a geographic community benefit from widespread vaccination, all members of the business community benefit from widespread immunity to government (or competitor) surveillance. The ability to keep communications private allows employees to innovate and collaborate, without their ideas getting scooped by competitors. Private web browsing allows talented professionals to find and apply for your job openings, without fearing that their current employer will notice. Private payment systems allow customers to buy your products, even if they are personal or embarrassing.

But, as with herd immunity, the benefits of privacy are available only if a critical mass of companies and individuals make the effort to protect it. Widespread adoption of privacy tools sustains the market for strong encryption and security software – a field that demands constant innovation to stay ahead of both hackers and government surveillance. Widespread adoption of privacy practices ensures that companies can use privacy-enhancing tools whenever they need them – without being flagged as suspicious. And widespread caution about collecting and retaining data prevents governments (or data brokers) from getting access to datasets that can be used to profile and target specific individuals.

Implementing strong privacy safeguards comes at a personal or business cost, however small: it takes a little bit of extra time and a little bit of extra effort, in part because existing privacy tools aren’t always easy to use. (Again, if more companies adopted strong privacy practices, it would help create market demand for better and more usable tools.) For those of us who put a lot of personal information online in the context of building a social media presence, there is also the potential reputational cost of sacrificing a little bit of visibility or engagement in favor of some degree of discretion.

In urging companies and individuals to assume these small costs, Snowden sounded much like vaccination advocates who encourage each of us to do our part for herd immunity. As with vaccination, it’s tempting to let other people do the heavy lifting: as long as a critical mass of companies use privacy-enabling tools like encryption and anonymized browsing, you know those tools will be available whenever you or your employees need to use them, so it’s easy to forego individual vigilance.

If, on the other hand, unsecured web browsers are the norm in corporate environments, a company that does use the anonymizer Tor or encourages employees to use their “private browsing” option looks like a company with something to hide. If the vast majority of transactions are itemized and trackable through loyalty cards, credit cards and social login, the transactions your customers keep private start to look suspicious. If companies collect and retain large amounts of data – even data that looks innocuous – it helps build the datasets that governments and some businesses (like insurance companies or advertisers) can use to profile, target and advantage (or disadvantage) specific individuals. And if companies cut corners in network design or data management, they make all that data accessible to hackers as well as government intelligence agencies.

Rather than eroding the expectation of online privacy, companies can and should help to build it. Big data is now the name of the game, but as Snowden said on Monday, “you should only collect the data and hold it for as long as necessary for the operation of the business”; any additional data represents a risk for your customers and for your business. Companies can protect the privacy of the data that they do collect by ensuring that all drives and network communications are encrypted. And as Snowden argued, companies not only have a responsibility to encrypt communications (something too many companies have done only since Snowden’s revelations came to light), but to develop technologies that protect privacy in a “simple, cheap, effective way that is invisible to users.”

Companies that take these measures are not only contributing to a business environment in which privacy is the norm: they’re also building value for their own shareholders. A company’s networks and security are only as strong as its weakest link: a single employee using a low-security password may be all it takes to compromise corporate systems. It’s not enough for a business to trust that generalized security and privacy norms will provide herd immunity for the free market: each and every organization has an immediate stake in encouraging its employees to adhere to the highest security standards.

And that’s what makes me hopeful that not only SXSW attendees, but the larger business community, will heed Snowden’s call to arms. Companies have self-interested reasons (as well as a legal duty) to drive stronger security practices. But it’s up to each and every company to do its part.

Craigslist Saved Consumers a Lot of Money While Crippling Newspapers

Craigslist, the online-ad site, saved the placers of classified advertisements $5 billion from 2000 through 2007, according to an analysis by Robert Seamans of New York University and Feng Zhu of Harvard Business School. It also had a profound impact on U.S. local newspapers, siphoning off classified advertisers and leading to decreased classified-ad rates, increased subscription prices, reduced circulation, and declines in display advertising. It also set up a consumer expectation that classified advertising would be free.

Why Good Managers Are So Rare

Gallup has found that one of the most important decisions companies make is simply whom they name manager. Yet our analysis suggests that they usually get it wrong. In fact, Gallup finds that companies fail to choose the candidate with the right talent for the job 82% of the time.

Bad managers cost businesses billions of dollars each year, and having too many of them can bring down a company. The only defense against this massive problem is a good offense, because when companies get these decisions wrong, nothing fixes it. Businesses that get it right, however, and hire managers based on talent will thrive and gain a significant competitive advantage.

Managers account for at least 70% of variance in employee engagement scores across business units, Gallup estimates. This variation is in turn responsible for severely low worldwide employee engagement. Gallup reported in two large-scale studies in 2012 that only 30% of U.S. employees are engaged at work, and a staggeringly low 13% worldwide are engaged. Worse, over the past 12 years these low numbers have barely budged, meaning that the vast majority of employees worldwide are failing to develop and contribute at work.

Gallup has studied performance at hundreds of organizations and measured the engagement of 27 million employees and more than 2.5 million work units over the past two decades. No matter the industry, size, or location, we find executives struggling to unlock the mystery of why performance varies so immensely from one workgroup to the next. Performance metrics fluctuate widely and unnecessarily within most companies, in no small part from the lack of consistency in how people are managed. This “noise” frustrates leaders because unpredictability causes great inefficiencies in execution.

Executives can cut through this noise by measuring what matters most. Gallup has discovered links between employee engagement at the business-unit level and vital performance indicators, including customer metrics; higher profitability, productivity, and quality (fewer defects); lower turnover; less absenteeism and shrinkage (i.e., theft); and fewer safety incidents. When a company raises employee engagement levels consistently across every business unit, everything gets better.

To make this happen, companies should systematically demand that every team within their workforce have a great manager. After all, the root of performance variability lies within human nature itself. Teams are composed of individuals with diverging needs related to morale, motivation, and clarity — all of which lead to varying degrees of performance. Nothing less than great managers can maximize them.

But first, companies have to find those great managers.

If great managers seem scarce, it’s because the talent required to be one is rare. Gallup finds that great managers have the following talents:

They motivate every single employee to take action and engage them with a compelling mission and vision.

They have the assertiveness to drive outcomes and the ability to overcome adversity and resistance.

They create a culture of clear accountability.

They build relationships that create trust, open dialogue, and full transparency.

They make decisions that are based on productivity, not politics.

Gallup’s research reveals that about one in ten people possess all these necessary traits. While many people are endowed with some of them, few have the unique combination of talent needed to help a team achieve excellence in a way that significantly improves a company’s performance. These 10%, when put in manager roles, naturally engage team members and customers, retain top performers, and sustain a culture of high productivity. Combined, they contribute about 48% higher profit to their companies than average managers.

It’s important to note that another two in 10 exhibit some characteristics of basic managerial talent and can function at a high level if their company invests in coaching and developmental plans for them.

In studying managerial talent in supervisory roles compared with the general population, we find that organizations have learned ways to slightly improve the odds of finding talented managers. Nearly one in five (18%) of those currently in management roles demonstrate a high level of talent for managing others, while another two in 10 show a basic talent for it. Still, this means that companies miss the mark on high managerial talent in 82% of their hiring decisions, which is an alarming problem for employee engagement and the development of high-performing cultures in the U.S. and worldwide.

Sure, every manager can learn to engage a team somewhat. But without the raw, natural talent to individualize; focus on each person’s needs and strengths; boldly review their team members; rally people around a cause; and execute efficient processes, the day-to-day experience will burn out both the manager and his or her team. As noted earlier, this basic inefficiency in identifying talent costs companies hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

Conventional selection processes are a big contributor to inefficiency in management practices; little science or research is applied to find the right person for the managerial role. When Gallup asked U.S. managers why they believed they were hired for their current role, they commonly cited their success in a previous non-managerial role or their tenure in their company or field.

These reasons don’t take into account whether the candidate has the right talent to thrive in the role. Being a very successful programmer, salesperson, or engineer, for example, is no guarantee that someone will be even remotely adept at managing others.

Most companies promote workers into managerial positions because they seemingly deserve it, rather than because they have the talent for it. This practice doesn’t work. Experience and skills are important, but people’s talents — the naturally recurring patterns in the ways they think, feel, and behave — predict where they’ll perform at their best. Talents are innate and are the building blocks of great performance. Knowledge, experience, and skills develop our talents, but unless we possess the right innate talents for our job, no amount of training or experience will matter.

Very few people are able to pull off all five of the requirements of good management. Most managers end up with team members who are at best indifferent toward their work — or are at worst hell-bent on spreading their negativity to colleagues and customers. However, when companies can increase their number of talented managers and double the rate of engaged employees, they achieve, on average, 147% higher earnings per share than their competition.

It’s important to note — especially in the current economic climate — that finding great managers doesn’t depend on market conditions or the current labor force. Large companies have approximately one manager for every 10 employees, and Gallup finds that one in 10 people possess the inherent talent to manage. When you do the math, it’s likely that someone on each team has the talent to lead. But given our findings, chances are that it’s not the manager. More likely, it’s an employee with high managerial potential waiting to be discovered.

The good news is that sufficient management talent exists in every company – it’s often hiding in plain sight. Leaders should maximize this potential by choosing the right person for the next management role using predictive analytics to guide their identification of talent.

For too long, companies have wasted time, energy, and resources hiring the wrong managers and then attempting to train them to be who they’re not. Nothing fixes the wrong pick.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Developing Mindful Leaders for the C-Suite

Meet the Fastest Rising Executive in the Fortune 100

If President Obama Can Get Home for Dinner, Why Can’t You?

To Get Honest Feedback, Leaders Need to Ask

March 12, 2014

Research: CEOs Matter More Today Than Ever, at Least in America

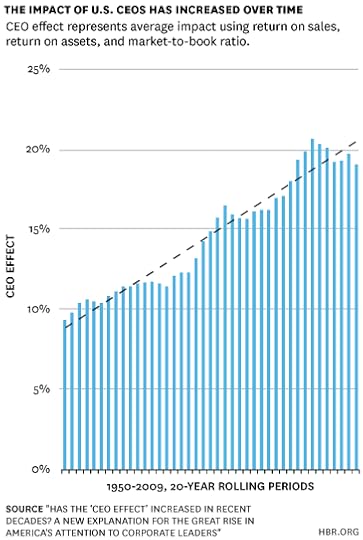

How much credit does the CEO deserve when a company is performing well? Is success really attributable to a single executive, or are economic and industry trends ultimately responsible? What about the rest of the organization? These questions are part of a rich research tradition that seeks to explain which factors account for a company’s performance. Particular attention is paid to a factor known as the “CEO effect,” which is the portion of company performance that is associated with who’s in charge.

A forthcoming paper by researchers at the University of Georgia and Penn State suggests that CEOs matter more than ever for U.S. companies, and takes a stab at explaining why. The new paper confirms a pattern discovered by previous research: the CEO effect seems to be increasing over time. In other words, the CEO of a company is a more significant predictor of that company’s performance than at any time since the question has been measured, starting in the mid-twentieth century. Moreover, the authors offer a relatively simple explanation, which is that CEOs simply matter more than they used to.

It’s important to note that this research can’t say anything about what makes CEOs important. The researchers tracked when CEOs took the reins at a representative sample of U.S. public companies, and then measured whether different CEOs presided over significantly different levels of performance, even after taking into account industry, firm, and year (which accounts for macroeconomic changes). The chart above shows an increase in the impact of CEOs on an average of three metrics: return on sales, return on assets, and market-to-book ratio.

The increase is undoubtedly interesting, but which is more surprising: that CEOs seem to matter significantly today, or that they mattered so much less in the mid-twentieth century? As the authors write:

In the period 1950-1969, company performance in a given year was due overwhelmingly to factors that were relatively easy to comprehend, notably macro-economic conditions, industry factors, and the firm’s overall health and position. By the period 1990-2009, these straightforward contextual factors were not nearly as predictive of performance.

In the period from 1950 to 1969, for instance, just knowing the industry a company was in predicted 38.7% of differences in performance. By contrast, from 1990 to 2009 industry predicted only 3.7% of the difference. That gap is telling, and the authors see it as evidence that what has changed goes well beyond CEO leadership. A combination of forces — including the shift of emphasis toward maximizing shareholder value and the role of technology in increasing the pace and complexity of business in countless sectors — made business more dynamic and less predictable. It’s against that backdrop that CEOs have been empowered to pursue new strategies and markets, often across the globe. The result has been an increase in CEO impact.

It’s worth noting that other research has found the CEO effect to vary considerably between industries, in somewhat counter-intuitive ways. The more resources a CEO has at his or her disposal to invest, the more their decisions will tend to matter (for good or ill) — that fits broadly with the conclusions drawn in this new research paper. On the other hand, high-growth industries have been shown to be less subject to the CEO effect, because the plethora of opportunities for success make it easier for mediocre executives to succeed. Taken with this new research, this suggests something of a paradox: an increase in business dynamism has amplified the impact of CEOs over time, but that effect is at its highest in companies where industry and economic constraints still limit the firm’s options.

There is one final explanation that the new paper’s authors consider, and that is that markets simply think CEOs matter more, and naively bid their share prices up and down accordingly. They can’t rule this possibility out, and that uncertainty is telling in that it reinforces their most interesting conclusion. American business has become more unpredictable in recent decades. CEOs may in fact matter more as a result, but so too do forces we do not fully understand.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers