Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1451

March 20, 2014

What Does Professionalism Look Like?

When we talk about “professionalism,” it’s easy to fall back into the “I know it when I see it” argument.

For Emily Heaphy, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at Boston University, and her colleagues, this isn’t a cop-out. The notion of being seen as professional may be central to how we define success in the U.S. — and, consequently, how and why certain people aren’t able to attain it, depending on how well they adhere to social norms. In particular, Heaphy and the other researchers set out to study “one potential culturally bounded workplace norm — that of minimizing references to one’s life outside of work.”

They did this in two ways: First, they tested how people connect perceptions of professionalism to what a worker’s desk looked like. Second, they examined how recruiters from two different countries rated potential employees who referenced family or children.

For the former, they presented study participants with this nondescript cubicle:

Along with the description of a fictional employee:

Eric is a manager in his mid-thirties, who has been with his company for five years. He is married and has two kids. Eric’s performance evaluations are consistently strong, and he is considered very professional.

Participants were asked to then use a selection of stickers to decorate Eric’s office based on their mental image of what it might look like. Some stickers clearly referenced work (file folders, for example), others were neutral (a tissue box), and some referenced nonwork (children’s drawings or toys). On average, this is what Eric’s office ended up looking like:

When one word in Eric’s description changed, however (“he is not considered very professional”), his cubicle looked like this:

The differences are small but striking. While both professional and unprofessional Eric have office supplies and family photos in their cubes, unprofessional Eric also makes use of what appear to be holiday decorations, a poster of Elmo, and a Discman. It’s noteworthy, Heaphy told me, that the number of objects remained similar in both scenarios — in other words, you can’t simply say that an unprofessional person is messier.

Heaphy and her colleagues also asked participants to complete the same exercise with a female employee named Stephanie. Interestingly, they found no statistically significant differences in how professionalism was gauged based on gender:

But there was a significant difference in judging professionalism when they looked at how long participants had worked in the U.S.

This suggests that filling one’s office with strictly work-related items “is learned with experience living in the United States rather than a culturally universal feature of appropriate workplace behavior.”

So why is this important?

For one, it highlights how deeply rooted religious ideology still is in America. Heaphy and her co-authors trace what’s unique about the U.S. — “maintaining unemotional, polite, and impersonal workplace interactions” — to what’s referred to as the “Protestant Relational Ideology.” Basically, this is a theory originally developed by political economist Max Weber and based on “the need to put aside personal concerns to devote full attention to one’s work so as to fulfill one’s moral and spiritual calling.” It may sound out-of-date, but its effects aren’t. In one depressing example, a recent paper about unemployment found that “psychic harm from unemployment is about 40 percent worse for Protestants than for the general population.” In another, women with children reported receiving unfair treatment when they violated the norm that “workers should devote full time, uninterrupted hours to paid work.”

Related, but perhaps even more significant, is how cultural norms affect today’s more global business environment. Just as it’s no longer true that “work” means “being in an office from 9-5,” it’s no longer the case that Indian businesspeople stay in India, or that U.S. execs remain in the States. “Confusion about a tacit norm… is only enhanced by the growing globalization of the workplace that increasingly brings workers together across national borders,” write the study’s authors. This can “result in misinterpretations and misunderstandings.” In fact, one of the most important things people must do when working in new cultures “is to discover and respect the norms of their new setting, or suffer the consequences.”

But right now, those consequences might unfairly be pushing — or at least excluding — non-Americans.

And what if U.S. businesspeople work abroad?

“The question we don’t have the answer to is, ‘What are the ways people evaluate professionalism in other countries?’” Heaphy explained, referring to the dearth of scholarly literature on workplace norms worldwide. “In the U.S., with a Protestant Relational Ideology, you need to be completely devoted to work. We don’t have a similar theory as to why other countries would be different.” But given the chart above, we can guess that they likely are.

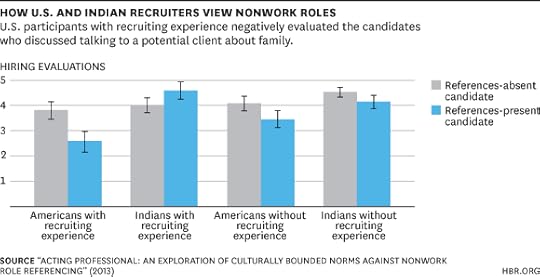

This assumption is further evidenced by the next portion of the same study. Researchers asked American and Indian participants to evaluate a job candidate based in part on how he or she would build rapport with a potential client. In one set of circumstances, the candidate would make reference to a photo of the client’s family; in the other, he or she would only discuss the location of the office or the view out the window. Participants were then asked whether they would recommend hiring the candidate.

While there was no statistical difference between Indian and American participants when it came to the latter example, the researchers found that “U.S. participants with recruiting experience negatively evaluated the candidate who engaged in nonwork role referencing, whereas Indian participants with recruiting experience did not.” In addition, “Job candidates’ success in advancing to the next stage of the hiring process was increased when they minimized references to nonwork roles in a U.S. but not Indian context.”

Much more research needs to be done in this area, according to Heaphy, including these potential paths: When, and under what conditions, might cultural ideologies of professionalism change? Do men and women feel as though they have different leeway in terms of displaying personal items? And do different types of workplace items or discussions — say, ones related to sports or family — illicit different reactions when people are trying to make sense of professionalism?

Though I wouldn’t necessarily reserve judgment on the colleague who still uses a Discman.

Malaysia Airlines Managers Could Have Had Better Data at Their Fingertips

Unprecedented disasters nearly always yield 20/20 hindsight, and lead to narrowly-conceived, “never again” style reforms. But sometimes the lessons are more broadly useful. In the case of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, the most impressive fact few reporters choose to explore in any depth is that the Boeing 777’s engine was capable of communicating long after the pilots went silent. And the tragedy is that all the information it was able to convey was not actually transmitted.

If the news media were more tech-oriented, they would report this as an Internet of Things (IoT) story. The term refers to the fact that billions of sensors and devices are connected to the web, automatically transmitting, receiving, and taking action on data. Now that, in fact, they far exceed the number of connected humans on the planet, we have an Internet of “things” more than people.

The data that eventually showed that Flight 370 continued for hours after voice transmissions ended came from satellite pings, most notably provided by Inmarsat. But more precise data could have come more directly from the plane’s Rolls-Royce Trent 800 jet engines – almost all Rolls-Royce engines produced in the recent past are IoT-enabled. While many major industries have yet to create “IoT” products, that’s not the case with jet turbines. Thanks to their cost, the very strong interest in running them efficiently, and the enormous safety implications of their maintenance, it has been easy to justify the added costs of building in sensors that transmit information about the engine’s operating conditions to the ground in real time. All manufacturers now routinely include 60 or so such sensors on their models. (Evidently these engines, because they were older, had add-on sensors, not the built-in ones, but the point is the same.)

This data allows the manufacturers and their customers to do things that were simply impossible in the past. Instead of scheduled maintenance, whose intervals are typically based on imprecise measures such as mean-time-to-failure, they can now offer airlines “predictive maintenance,” which is done when each individual engine actually needs it, as indicated by real-time data from the engine such as detection of a hairline stress fracture that may not be visible. That’s not only cheaper, but can also avoid a catastrophic in-flight failure.

The IoT turbine also offers the manufacturer a marketing option: instead of selling the turbine, they can instead offer an airline a lease where the price is determined dynamically, based on the precise data about how far the engine is flown, or they can offer fixed-price maintenance agreements that work because the company can avoid unscheduled repairs.

So why didn’t engine data help in the search? Because the airline had the option, but declined, to pay about $10 per flight for real-time access to it. Had it chosen to make the investment, it might have done so in order to tweak the engines for maximum performance – but in doing so, it would also have gained the ability to keep tabs on a wayward plane. Looked at in this light, the terrible delay in finding Flight 370 can be seen as a failure of management practice to keep up with new technology.

IoT experts I’ve consulted about this idea think it’s likely that the data from the Rolls-Royce engine was probably in an “open” (vs. proprietary to the company) format that would have allowed it to have been shared, as it was generated, with the airline, and even the flight controllers. That would have meant that, when voice contact ceased, they could have switched to the engine data. Because they would have seen that the plane was still flying, there might even have been time to take measures to avert loss of life. Instead, this data only surfaced days later: still critical, but not actionable.

My take on this lapse is that there’s a gap between the power of IoT technology, and management’s ability to conceive strategies to capitalize on it, which I refer to as “IoT Thinking.” In particular, managers have yet to wrap their heads around a new design imperative: That as we design things to be part of the Internet of Things, we must constantly ask: who else could use this data? Many of the potential benefits of real-time IoT data can only materialize if we envision multiple users.

Here’s a simpler example to illustrate what I am saying. I recently saw a vending machine prototype enabled by IoT technology, mainly with customized marketing in mind. It can recognize a customer, offer her a special package (perhaps a price break on a soda plus chips) based on her past buying choices, and even adjust prices dynamically based on outside air temperature. (Someday you might regret saying, “I’d pay anything for a cold drink right now!”). However, the developers didn’t stop there: they asked what I think has to be a fundamental question with the IoT (and one we just haven’t asked in the past, when proprietary data was the route to fame and fortune): “ who else might have use for this real-time data?” In this case, they realized that the machine’s sensors could also detect when the inventory level in the machine was low. If that data were relayed (again, in real-time) to a distributor, it could be feasible for a delivery truck to have its route dynamically rerouted to replenish the machine. One data stream, many uses.

Similarly, manufacturers will be able to dramatically improve supply-chain integration and their distribution, while optimizing assembly line efficiency by building in sensors throughout the assembly line, and spreading that data to everyone, from assembly line workers to supply-chain partners, who can use it.

Given this new reality, aviation safety authorities should consider mandating that engine manufacturers in the future routinely provide the data stream to airlines and the flight controllers — and that the companies monitor it. (That’s quite simple: all they need to do is program alerts for the relatively rare exceptions when the data deviates from norms).

Smart airlines may take the initiative and demand the data now. My sources in the industry say that some airlines use this real-time data to tweak engine performance, a competitive advantage. (After the BP blow-out disaster, I suggested that the same approach would be applicable to drilling platforms. And it would be ideal in the event that the Obama Administration approves the Keystone XL pipeline: a built-in sensor could detect a stress fracture before any visible evidence, then automatically trigger a shutdown. Not a drop of oil would be spilled and the company would know exactly where to go, speeding repairs and restarting the pipeline quicker.)

The Internet of Things’ ability to share real-time data among many users simultaneously has many advantages to everyone who has access to it. Not least of these is the potential to save lives.

How Robots Will Work with Us Isn’t Only a Technological Question

Many questions remain unanswered about how humans and robots will interact, including in the workplace. We just know that many more of these interactions will be taking place, as robots continue to play a greater role in our lives. Missing from many of our conversations about robots is the role of human robotic interaction (HRI) – we tend to focus on what robots can do, more than how we will work with them.

This question is critical, and its answer is ultimately dependent on questions of design. How we design our robots will shape how we work with them. In thinking about how to design our robots, a service framing is beneficial: who are a robot’s customers? The answer goes beyond those directly involved in interacting with the robot to include additional stakeholders such as families and supporters, medical staff, trained professionals such as dieticians and personal trainers, restaurants and food service providers, and even policy and lawmakers. The presence of robots will change how humans behave in ways we don’t yet fully understand, and the choices we make in designing them will help determine how.

A few years ago at Carnegie Mellon, we developed a robot, the Snackbot, along with a snack delivery service, to explore these questions. A service design framing helped us to develop the robot holistically, rather than merely seeking to advance autonomous technology. Stakeholders included customers, others in the workplace, the robot developers, designers, and researchers, the robot’s assistants, and the people who obtain and load the snacks on the robots. The context of use and the norms of the workplace also needed to be considered. A product-service system was developed to track information about behavior and preferences over time. Knowledge about how the technology influenced human behavior and how human behavior influenced the technology was used to tune the robot’s design.

Our findings, published in 2012, only confirmed how greatly design decisions weigh in shaping our behavior when dealing with robots. First, we found that that subjects anthroporphized the robot, saying things like “Snackbot doesn’t have feelings, but I wouldn’t want to just take the snack and shut the door in its face.” Second, we found that the presence of the Snackbot caused both positive and negative ripple effects in the workplace, leading to new and different interactions between coworkers as colleagues observed each others’ interactions with the robot.

Finally, we experimented by personalizing Snackbot, so that it would speak to participants drawing on knowledge of their previous interactions. In many cases, this seems to have deepened participants’ interests in interacting with the robot over time. We saw signals of trust and rapport, for example when people dressed the robot up in hats and beads, and when a customer brought Snackbot a snack — a battery — after the robot died one day in front of her office. In another case, the robot’s commenting on subjects’ snacking history led to discomfort from subjects who preferred not to be reminded of the junk food they ordered the previous day. Clearly, the choice of whether or not to personalize the robot’s service affected how humans interacted with it.

As we consider the role that robots will play in our offices and in our lives, we must remember that their capabilities are not simply defined by the cutting edge of technology. They are also the result of the design choices that we make.

Fixing a Weak Safety Culture at General Motors

On Monday, GM CEO Mary Barra apologized for 12 deaths and 31 accidents linked to the delayed recall of 1.6 million small cars with a defect in the ignition switches, saying the company took too long to tell owners to bring the cars in for repairs. The switches could, if bumped or weighed down by a heavy key ring, cut off engine power and disable air bags.

The question I ask here is not how and why did this dangerous defect occur, but rather what kind of company culture allows passenger safety to be so badly compromised?

Let’s start with the facts as we can glean them.

Fact 1: Broken communication channels. Reports on exactly when (and how) GM’s top executives learned about the switches vary. According to one report: “The company has acknowledged it learned about the problem switches at least 11 years ago, yet it failed to recall the cars until last month.” According to another, “GM has said the issue was discovered as early as 2001, and in 2004, a company engineer ran into the problem during the testing phase of the soon-to-be-released Chevrolet Cobalt.”

Fox Business reported, “Barra found out about a review of the Cobalt in December, when she was still head of GM’s global product development.” In an article on the recall in The New York Times, Barra claimed she didn’t “know the serious nature of the defects until Jan. 31,” two weeks after she became CEO, “when she was informed that two safety committees had concluded that a recall was necessary.”

This unawareness at the top would be impossible in an organization with a strong safety culture. In fact, the single-most-important attribute of such a culture is proactive and timely voice related to failures, a topic I have studied and written about extensively.

This willingness to speak up is especially true for the small and seemingly inconsequential discrepancies that can, when unreported, give rise to catastrophic failures later. Any organization can detect big, expensive failures! It’s the great companies that detect the small ones that otherwise go unnoticed. And, when news related to potential failures is withheld as long as humanly possible, safety is the first victim. Although all too human, the tendency to withhold — to wait and see — is driven out of organizations with strong safety cultures.

Fact 2: A recall. GM has recalled 1.62 million vehicles globally.

Certainly, the right thing to do is to show concern and to solve the problem. But that’s hardly a choice at this point.

Fact 3: An apology. Meeting with reporters, Barra said: “I want to start by saying how sorry personally and how sorry General Motors is for what has happened. Clearly lives have been lost and families are affected, and that is very serious.” In a video to GM employees, Barra apologized again, saying, “Something went wrong with our process in this instance, and terrible things happened.” David Cole, the former head of the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the son of a former GM president, said it was the first time in his memory that a GM CEO has apologized for a safety problem. In fact, it’s more dramatic than that. As The New York Times reported, “corporate chiefs routinely avoid talking about recalls [period] unless subpoenaed by Congress.”

Barra’s apology is thus a strong and powerful step in the direction of building a safety culture at GM.

Fact 4: A new safety leader. On Tuesday, March 18, Barra named a new head of global safety, Jeff Boyer. She pledged to meet with him on a monthly basis and offered this description of how he would function in the organization: “Jeff’s appointment provides direct and ongoing access to GM leadership and the Board of Directors on critical customer safety issues… This new role elevates and integrates our safety process under a single leader so we can set a new standard for customer safety with more rigorous accountability. If there are any obstacles in his way, Jeff has the authority to clear them. If he needs any additional resources, he will get them.”

Creating a new leadership position focused on safety is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it shows seriousness of purpose. On the other, it risks compartmentalizing safety — which needs to be everyone’s job.

Fact 5: Product assurances. Barra further promised to repair all broken vehicles (and to double the number of product reviews). She has offered a $500 cash allowance to owners of recalled vehicles and asking dealers to offer loaner cars while their vehicles are in the shop for repairs.

This builds goodwill among customers, but doesn’t directly build a culture of safety within the company.

Fact 6: An internal investigation. Barra has launched an investigation internally at GM, which is expected to take about seven months to finish.

Learning from failure is one of the most important activities that occurs in great organizations, so this step is essential. But, of course, how the investigation is handled can make or break its usefulness. Is the point to find the culprits? Or to find out what happened, and what the company can do to make sure it never happens again.

All the actions that Barra has announced are good. Yet questions remain — including how could someone as product savvy as Mary Barra have had no prior knowledge of these issues?

Clearly, GM’s safety culture is, and has been for quite some time, badly broken. A strong safety culture stems from psychological safety — the ability, at all levels, to speak up with any and all concerns, mistakes, failures, and questions related to even the most tentative issues. Simply appointing a safety chief will not create this culture unless he and the CEO model a certain kind of leadership.

Consider the case of Allan Mulally. Soon after being hired as Ford’s CEO, Mulally instituted a new system for ensuring that he learned about problems. Understanding how difficult it is for bad news to make it up the corporate hierarchy, he asked managers to color code their reports: Green for good, yellow for caution, red for problems. He was frustrated when, during the first couple of meetings, all he saw was green. It took considerable prodding before someone spoke up, tentatively offering the first yellow report. After a moment of shocked silence in the group, Mulally applauded, and the tension was broken. After that, yellow and red reports came in regularly.

The failure to speak up about safety and other problems is not unique to car companies. Silence and shooting the messenger remains the norm in far too many companies, and this won’t change unless leaders proactively invite and embrace messages of small, large, and potential failures. To do this, leaders need to override human nature by practicing two crucial behaviors that keep bad news coming early and often:

Embrace the messenger. In a strong safety culture, leaders understand the risks of unbridled toughness. A punitive response to an employee mistake will be more effective in stifling future news of problems than in preventing them. A company’s ability to detect and solve problems is absolutely crucial to its ability to learn about them.

Reward problem detection. Failures must be exposed as early as possible to enable learning in an efficient and cost-effective way. In an interview with the McKinsey Quarterly, Mulally illustrated the shift this entails: “For example, an employee decides to stop production on a vehicle for some reason. In the past at Ford, someone would have jumped all over them: ‘What are you doing? How did this happen?’ It is actually much more productive to say, ‘What can we do to help you out?’ Because if you have consistency of purpose across your entire organization and you have nurtured an environment in which people want to help each other succeed, the problem will be fixed quickly. So it is important to create a safe environment for people to have an honest dialogue, especially when things go wrong.”

These behaviors go a long way toward building the robust climate of psychological safety that is the foundation of a strong safety culture. Companies that have this are far less vulnerable to physical safety failures that can harm customers, employees, and communities.

Helping a Bipolar Leader

I think we all know somebody like John (not his real name), a talented executive I once coached. He had extraordinary drive and charisma. The people reporting to him all agreed that he had provided outstanding leadership in the company’s last crisis; his refusal to bow to adversity and his ability to rally people behind him had been truly remarkable.

But they also agreed he could go over the top. There were the e-mails sent at 2 AM, and it was sometimes hard to follow exactly what he was saying. He would jump suddenly from one idea to another and some of his plans seemed unrealistic, even grandiose. And whenever anyone tried to slow him down, John wouldn’t hear of it. His sense of invincibility made him feel that he could do anything. Once he had made up his mind, it was almost impossible to change it. His inability to listen coupled with his lack of judgment eventually resulted in his making a number of seriously bad decisions, plunging his unit into the red. The board had considered firing him, but decided to give him another chance and called me in to coach.

I am a psychologist as well as a coach, so I realized that John suffered from a mood disorder called bipolar dysfunction, previously known as manic depression, a condition that haunts approximately 4% of the population. People suffering from this condition report periodically experiencing an overactive mind and often seem to get by on little or no sleep. They often feel a heightening of the senses, which may trigger increased sexual activity, and are highly prone to bouts of extravagant behavior. Their moods swing wildly from this state of exuberance to the polar opposite, and they suddenly can become withdrawn and inert, shunning the company of others. When that’s the case (far from surviving on no sleep), they struggle to get out of bed.

It’s a condition often associated with highly creative people. William Blake, Friedrich Nietzsche, Ludwig Von Beethoven, Edgar Allen Poe, Vincent Van Gogh, and Ernest Hemingway all reported going through similar cycles of mania and depression. So do many of our most famous leaders, notably Theodore Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and General Patton.

As history shows, manic-depressive leaders like these are great in a crisis, refusing to bow to adversity. They rush in where others feared to tread and can inspire others to follow. The downside is that due to their extreme sense of empowerment, energy and optimism, their thinking and judgment can be flawed. Caught up in their grandiosity, they overestimate their capabilities and try to do more than they can handle. The problems are often aggravated by an inability to recognize that their behavior is dysfunctional. While “high,” they rarely have insight into their condition. They like the sense of invulnerability that comes with the “high,” and are reluctant to give that up.

When the inevitable setbacks and disasters happen, they fall into a tailspin of depression. This had just happened to John, who had gone so far as to check himself into a hospital psychiatric ward for a brief stay. Adding to his woes, his wife asked for a trial separation. Apparently John had been reckless with his personal finances and had been involved in numerous affairs.

Despite the challenges, people like John can be helped and put on a more even keel. When they’re manic, there’s little you can do, but when they are depressed they can be receptive to counseling. The key to getting them to a better place is to help them build more structure in their lives, both personal and professional. In relatively mild cases of bipolar dysfunction, this may be sufficient to stabilize the person in question. In more extreme cases, sufferers will eventually need psychotherapy and medication. But the initial step of building some structure will at least make them more amenable to considering these options.

Counseling bipolar people can be problematic for people without psychological experience because it may involve crossing a few boundaries. As I explain in in my HBR article, to help truly extreme cases I believe in creating alliances with the other important people in their lives. In John’s case, I insisted on having number of conversations with John’s wife, both alone and also with John. While unorthodox, my goal in these conversations was to help John figure out how she saw their futures and whether their futures lay together. We explored various scenarios. By getting some clarity around what future John wanted and whom he wanted in it provided him with some psychological anchors and gave him an incentive to do something about his condition.

Discussing his future, it began to dawn on John (reflecting on his strengths and weaknesses), what his best fit was in the organization. He came to realize that getting involved in too many details of the business created too many distractions. What he really seemed to be good at was cutting big deals with important clients. It became also clearer to John that he needed a work structure that allowed him to focus his energy at work and give him emotional space for his family.

At this stage, John, the board, and I agreed that his job needed to be defined in a way that allowed him to focus on the big deals, leaving the day-to-day work to others. Since John moved into this new role, his 360-degree feedback has improved steadily; while he remains volatile, he seems better able to moderate himself. It also looks like his relationship with his wife has improved. He takes medication regularly and sees a therapist. The company has benefited from its willingness to help John with his condition by retaining his talents and drive. I think many companies are too quick to punish executives for the consequences of their bad decisions. A better approach is to find ways to fix the (often quite manageable) psychological dynamic that so often lies behind those decisions.

Making the Gradual Retirement of a Co-Founder Work

Most people look forward to retirement. They can’t wait to play more golf with their pals, travel, hang out with the grandchildren, perhaps spend more time on non-profits, and generally pursue a more relaxed lifestyle. But some of us don’t really want to retire. Like my partner, with whom I co-founded our finance services company.

David is in a very slow process of retiring. It was inevitable that he would leave the company before me: he is 20 years older. This age difference is among the reasons that our pairing has been so successful; we have drawn clients from different generations, and David’s age enhances his aura of statesmanlike wisdom.

Slow retirements of senior executives present some of the same challenges to organizations as typical departures, and certain unique ones. For example, years in advance of his leaving, we addressed the critical, often financially painful, and sometimes insurmountable matter of redeeming our partner’s ownership stake. However, as difficult as the financial buy-out element is, the more complex problems relate to how to fill the slowly expanding void created by a gradual departure.

The slow retirement poses risks and challenges if handled poorly but can be a rewarding experience for the executive involved and his colleagues if managed carefully. Here are the principles we’ve been using to guide us; they may also be applicable at your firm:

Work out the financial ramifications quickly. In a financial firm like ours, holding growth aside, the pressure comes from two sources; the purchase of the partner’s shares by existing or new partners, and compensation needed to bring in new talent. In any firm, unless the departing executive makes concessions, the company will have to balance the outgoing executive’s existing salary (and any retirement package) with the cost of bringing in a replacement. When David passed his CEO title over to me, becoming Chairman, we explained his ongoing specific job functions to everyone and the fact that his compensation would reflect those changes. This removed ambiguity and the likelihood of misconception about opportunities for others within the firm.

Think through the cultural ramifications. According to research by Langowitz and Allen, (link here) the success of new ventures is inextricably connected with the style and leadership of their founders, so companies need to be careful about maintaining cultural integrity when one of those founders leaves. Having a co-founder leave slowly will have a more muted effect than a sudden exit, but the benefit can disintegrate if he is there but not engaged in what suits his interests and the enterprise needs. In our case, this culture includes our relationships with clients. Clients adore David and he loves working with them, so these relationships will be the last element of his job to transition. We have informed all clients of the process and always have two partners assigned to each account. However, we need to both include a third member to each client team and establish the chronology for handover. I know this will be the toughest aspect to his retirement and I am not anxious for its arrival.

Design a hover-limited environment. No one will want to step up to a position if the gradually retiring executive will be either hovering or reassuming that assignment. If you won’t own the job, why take it? Think of Warren Buffet or of Pimco, both of whom have hired and then lost their apparent successors, who either grew impatient waiting or annoyed with the meddling. Reassure your veteran colleague that he or she is helpful and respected but be honest about responsibilities and limits. The lifeblood of any investment company is making investment decisions and David has made many since we started our firm nine years ago. Over time, we have successfully added personnel to our investment professional ranks. While David is still passionate about helping craft our strategy and implementing these moves, this is the area where we can least afford limited capacity. Like a fishing boat cruising through a barren stretch of sea, we can’t be fooled by a lull in activity, but need staffing to discover, analyze, and invest in opportunities that might suddenly emerge from price changes.

For example, each quarter David has traditionally written a topical investment piece, which we send to all clients. We have encouraged other team members to broach themes about which, after colorful group discussions, they write themselves and we send to all our constituents. This introduces other colleagues to our clients on a new dimension, increases their confidence in promoting ideas, and raises their profile internally.

Know your own strengths and weaknesses. Finally, if you are the CEO, but have had the benefit of a close partner with whom you shared responsibilities for building and overseeing a company, be grateful for that relationship, determine what you do well, what your partner did better, and envision the firm’s future with that in mind. We’ve considered the different operating lines of our company, with an eye toward transferring or reimagining responsibilities in an orderly progression as David pulls back from his involvement. Marketing and client development transitioned naturally from David to me and other partners because he had done so much in the early years of our enterprise that there were very few untapped contacts years later. To maintain our momentum and supplement our steady growth, we added an experienced executive who could direct both marketing and compliance, which has become an increasingly complex responsibility that I could no longer assume.

The trickiest aspect of the slow transition is, by definition, the lack of speed, which suggests that managing timelines and expectations are a key to success. We value David’s knowledge and input, but the next phase of our business growth involves younger people charged with independent decision making on which they will be judged. By the time I retire (maybe, but no promises), twenty years from now, when we are a much larger but still comfortably sized company, we will be experts at building experience and competence in a whole new generation of co-workers.

Don’t Let Patent Law Hold Back Interaction Design

Patent law is a powerful tool for encouraging innovation, but it’s also temperamental. As recent efforts to discourage patent trolls have shown, it’s not enough to simply enforce the rules; they must also be updated and fine-tuned to respond to the technology and economy around them. This is why the current state of patent law in interaction design is so alarming. What we have at the moment is a legal environment that hasn’t yet caught up to current technology, and the much-discussed “pinch-to-zoom” lawsuit makes it clear that this disconnect is starting to be a drag on innovation.

To be effective, patent law must carefully distinguish between two things: the unique combination of information, cues, and actions that define a specific innovation (the embodiment) and the underlying building blocks that make it possible (the elements). It makes sense, in other words, to protect a book or a painting from being reproduced without permission, but it would be absurd to copyright an element such as the word “next” or the color blue, and we wouldn’t even try. In choosing to protect the specific embodiment (article, photograph, song, etc.) but not the individual elements (words, colors, notes), our laws generally do a good job of protecting creative work without inhibiting others from following suit.

One glaring exception to this balance, for designers and entrepreneurs at least, is the arena of digital interaction. The law simply doesn’t match reality when it comes to the ways we interact with our digital devices, and this is having a real impact on innovation. In the case of Apple versus Samsung, what’s been successfully patented isn’t a technological advancement, or even a branded visual identity, but a human gesture that’s as fundamental as rotating a knob to adjust volume, or giving a thumbs-up to express approval. Gestures, I would argue, are universal elements of interaction, as basic to the creation of new experiences as words are to poetry.

Patenting gestures and basic workflows is destructive because they aren’t just arbitrary actions dreamed up by one company or another, but ways of manipulating the world, hardwired into human brains by evolution and cultural conditioning. Interaction design is a younger discipline than graphic or industrial design, and much of its practice is still in the realm of basic discovery: finding the most efficient process for listing and choosing among ten options on a small screen, for example, or the most intuitive way to build and re-sort a playlist. These aren’t just aesthetic or emotional decisions, but deeply functional ones. No amount of clever coding or artful visual treatment can make up for their absence.

But the relative newness of interaction design also brings confusion, as the patent system struggles to figure out how to best regulate it. In the resulting debate, the loudest voices belong to large tech companies with deep pockets, ample legal resources, and strong motivation to discourage competition. This is why basic actions that any designer could tell you are part of the foundational language of human/device interaction – pinching to zoom, rotating a screen to change orientation, swiping to unlock a device – are repeatedly claimed as proprietary technology, and sometimes even upheld.

From inside the design studio or the startup office, this legal landscape presents a dismal view. So much of what makes or breaks a new digital venture – especially on a mobile device – is the experience of using it, and increasingly, the obvious path to the best experience is fraught with legal danger. There are hundreds of “right” ways to pick the color palette for a new product line or the shape of a mobile device, but a digital interaction often has a single best solution, because it’s essentially responding to the way your brain works. It’s not uncommon, in fact, for multiple designers working independently to arrive at the same solution to an interactive problem, despite having no contact with each other. When patent law awards protection to whoever discovered this solution first (or more likely, whoever had the legal resources to get it filed first), it does a very good job of scaring other designers and entrepreneurs away from using it. In my experience, it can even scare them away from expending the time and effort to try and find it.

That’s not what patent law is for, and I doubt it’s what lawmakers intended it to do. But by continuing to indulge lawsuits over fundamental action patents, US courts are actively discouraging innovation. As someone who has worked hard over the past 30 years to obtain dozens of patents, I deeply appreciate the value they have for business and for consumers. But unless we revise these laws to treat interaction design as sensibly as other creative fields, the future of technology will be a dim shadow of its true potential.

Algorithms Can Save Networking from Being Business Card Roulette

Networking can be something of a crapshoot. Though there may be someone in the room you really should meet — someone whose acquaintance might help you out professionally — it’s often impossible to determine who precisely that is. And so we go to industry conferences and share business cards like shotgun spray, hoping that with a little luck we’ll make a useful connection. In large organizations, the same thing goes for networking at company functions; surely there’s someone in another department it would be useful to know, but when scanning the room at the holiday party it’s not always clear who that is.

If this seems like a trivial issue, it’s actually anything but. Innovation, a critical component to success for today’s companies, is about coming up with new ideas. And generating new ideas involves recombining old ones in new and interesting ways. In practice, that means mixing people together, so that the information they share can be recombined into something new. That’s why companies go to great lengths to design offices that encourage spontaneous encounters, and why dense cities, where people can bump into one another on the street, are more innovative than sparser suburbs.

It’s also, at a theoretical level, why networking matters, and why a new academic paper on networking at conferences is so interesting. Researchers from the UK, Japan, and Italy set out to improve how networking happened at a scientific conference they were organizing. They asked all attendees to share which of the other attendees they knew, their own area of expertise, and subject areas or methods they were interested in learning. With this information, the researchers ran two rounds of “speed-dating” using algorithms designed to maximize the formation of new relationships. In the first round, participants met with others who were “far” from them in the conference social network, as well as “far” in terms of expertise. In the second, they looked for those who were “far” from each other in the network and who had expertise that the other was interested in learning.

This algorithmic speed dating ensured that the scientists were recombined in new ways, strengthening ties in the network that wouldn’t have existed and increasing the odds that each participant would make useful connections. It’s too early to tell if this approach yields quantifiable benefits, but the post-conference survey response was extremely positive. Notably, more than half the respondents indicated that “potential new collaborations were emerging from discussions at the meeting.”

“Of course, we have no objective baseline,” said Rafael Carazo Salas of University of Cambridge, one of the authors. But that doesn’t mean there couldn’t be one in the future. When I spoke with Carazo Salas he mentioned using Twitter or LinkedIn to quantify how the algorithmic matching compares to traditional networking in creating new connections. “In the case of science,” he continued, “you could go to grants co-submitted [or] patent applications filed,” to measure not just the effects on the network but the eventual impact on collaboration.

If such a measure of success could be found, it’s likely that this algorithmic approach to meeting people could transform networking both between and within businesses, much like it has for the online dating world. When you sign up for an Eventbrite event, an algorithm could suggest the people you’d most benefit from meeting there. Something similar could happen inside companies, with algorithms scanning email, intranets, and project management tools to suggest collaborators who might improve a project before it even gets off the ground.

No doubt some people will react negatively to the idea of algorithms deciding whom we should meet and collaborate with — not least the business development professionals whose networking acumen would potentially be less valuable. But society has grown used to it in the dating realm, and the conference goers in Carazo Salas’ experiment actually reacted more enthusiastically when they were told their pairings were the result of computation. Moreover, this kind of algorithmic matching already shapes the way we connect in the online world.

It’s still early days for this algorithmic approach to matching people, at least face-to-face and for the purposes of business and scientific productivity. But Carazo Salas and his colleagues are exploring the commercial applications of their experiment. “It’s all about innovation,” he told me. “By mixing things that are different, probably new things are going to come out.”

March 19, 2014

The Daily Routines of Geniuses

Juan Ponce de León spent his life searching for the fountain of youth. I have spent mine searching for the ideal daily routine. But as years of color-coded paper calendars have given way to cloud-based scheduling apps, routine has continued to elude me; each day is a new day, as unpredictable as a ride on a rodeo bull and over seemingly as quickly.

Naturally, I was fascinated by the recent book, Daily Rituals: How Artists Work. Author Mason Curry examines the schedules of 161 painters, writers, and composers, as well as philosophers, scientists, and other exceptional thinkers.

As I read, I became convinced that for these geniuses, a routine was more than a luxury — it was essential to their work. As Currey puts it, “A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods.” And although the book itself is a delightful hodgepodge of trivia, not a how-to manual, I began to notice several common elements in the lives of the healthier geniuses (the ones who relied more on discipline than on, say, booze and Benzedrine) that allowed them to pursue the luxury of a productivity-enhancing routine:

A workspace with minimal distractions. Jane Austen asked that a certain squeaky hinge never be oiled, so that she always had a warning when someone was approaching the room where she wrote. William Faulkner, lacking a lock on his study door, just detached the doorknob and brought it into the room with him — something of which today’s cubicle worker can only dream. Mark Twain’s family knew better than to breach his study door — if they needed him, they’d blow a horn to draw him out. Graham Greene went even further, renting a secret office; only his wife knew the address or telephone number. Distracted more by the view out his window than interruptions, if N.C. Wyeth was having trouble focusing, he’d tape a piece of cardboard to his glasses as a sort of blinder.

A daily walk. For many, a regular daily walk was essential to brain functioning. Soren Kierkegaard found his constitutionals so inspiring that he would often rush back to his desk and resume writing, still wearing his hat and carrying his walking stick or umbrella. Charles Dickens famously took three-hour walks every afternoon — and what he observed on them fed directly into his writing. Tchaikovsky made do with a two-hour walk, but wouldn’t return a moment early, convinced that cheating himself of the full 120 minutes would make him ill. Beethoven took lengthy strolls after lunch, carrying a pencil and paper with him in case inspiration struck. Erik Satie did the same on his long strolls from Paris to the working class suburb where he lived, stopping under streetlamps to jot down notions that arose on his journey; it’s rumored that when those lamps were turned off during the war years, his productivity declined too.

Accountability metrics. Anthony Trollope only wrote for three hours a day, but he required of himself a rate of 250 words per 15 minutes, and if he finished the novel he was working on before his three hours were up, he’d immediately start a new book as soon as the previous one was finished. Ernest Hemingway also tracked his daily word output on a chart “so as not to kid myself.” BF Skinner started and stopped his writing sessions by setting a timer, “and he carefully plotted the number of hours he wrote and the words he produced on a graph.”

A clear dividing line between important work and busywork. Before there was email, there were letters. It amazed (and humbled) me to see the amount of time each person allocated simply to answering letters. Many would divide the day into real work (such as composing or painting in the morning) and busywork (answering letters in the afternoon). Others would turn to the busywork when the real work wasn’t going well. But if the amount of correspondence was similar to today’s, these historical geniuses did have one advantage: the post would arrive at regular intervals, not constantly as email does.

A habit of stopping when they’re on a roll, not when they’re stuck. Hemingway puts it thus: “You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again.” Arthur Miller said, “I don’t believe in draining the reservoir, do you see? I believe in getting up from the typewriter, away from it, while I still have things to say.” With the exception of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart — who rose at 6, spent the day in a flurry of music lessons, concerts, and social engagements and often didn’t get to bed until 1 am — many would write in the morning, stop for lunch and a stroll, spend an hour or two answering letters, and knock off work by 2 or 3. “I’ve realized that somebody who’s tired and needs a rest, and goes on working all the same is a fool,” wrote Carl Jung. Or, well, a Mozart.

A supportive partner. Martha Freud, wife of Sigmund, “laid out his clothes, chose his handkerchiefs, and even put toothpaste on his toothbrush,” notes Currey. Gertrude Stein preferred to write outdoors, looking at rocks and cows — and so on their trips to the French countryside, Gertrude would find a place to sit while Alice B. Toklas would shoo a few cows into the writer’s line of vision. Gustav Mahler’s wife bribed the neighbors with opera tickets to keep their dogs quiet while he was composing — even though she was bitterly disappointed when he forced her to give up her own promising musical career. The unmarried artists had help, too: Jane Austen’s sister, Cassandra, took over most of the domestic duties so that Jane had time to write — “Composition seems impossible to me with a head full of joints of mutton & doses of rhubarb,” as Jane once wrote. And Andy Warhol called friend and collaborator Pat Hackett every morning, recounting the previous day’s activities in detail. “Doing the diary,” as they called it, could last two full hours — with Hackett dutifully jotting down notes and typing them up, every weekday morning from 1976 until Warhol’s death in 1987.

Limited social lives. One of Simone de Beauvoir’s lovers put it this way: “there were no parties, no receptions, no bourgeois values… it was an uncluttered kind of life, a simplicity deliberately constructed so that she could do her work.” Marcel Proust “made a conscious decision in 1910 to withdraw from society,” writes Currey. Pablo Picasso and his girlfriend Fernande Olivier borrowed the idea of Sunday as an “at-home day” from Stein and Toklas — so that they could “dispose of the obligations of friendship in a single afternoon.”

This last habit — relative isolation — sounds much less appealing to me than some of the others. And yet I still find the routines of these thinkers strangely compelling, perhaps they are so unattainable, so extreme. Even the very idea that you can organize your time as you like is out of reach for most of us — so I’ll close with a toast to all those who did their best work within the constraints of someone else’s routine. Like Francine Prose, who began writing when the school bus picked up her children and stopped when it brought them back; or T.S. Eliot, who found it much easier to write once he had a day job in a bank than as a starving poet; and even F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose early writing was crammed in around the strict schedule he followed as a young military officer. Those days were not as fabled as the gin-soaked nights in Paris that came later, but they were much more productive — and no doubt easier on his liver. Being forced to follow the ruts of someone else’s routine may grate, but they do make it easier to stay on the path.

And that of course is what a routine really is — the path we take through our day. Whether we break that trail yourself or follow the path blazed by our constraints, perhaps what’s most important is that we keep walking.

March 18, 2014

The Seven Skills You Need to Thrive in the C-Suite

What executive skills are most prized by companies today? How has that array of skills changed in the last decade, and how is it likely to change in the next ten years? To find out, I surveyed senior consultants in 2010 at a top-five global executive-search firm. Experienced search consultants typically interview hundreds (in many cases thousands) of senior executives; they assess those executives’ skills, track them over time, and in some cases place the same executive in a series of jobs. They also observe how executives negotiate, what matters most to them in their contracts, and how they decide whether to change companies. (For more on how executives set their work-life priorities, see this.)

Here are the seven C-level skills and traits companies prize most:

Leadership. The skills cited as most indispensable for C-level executives—not just CEOs—are those that jointly constitute leadership. One consultant described the search for a chief information officer in these terms: “Whereas technical expertise was previously paramount, these competencies [being sought today] are more about leadership skills than technical ones.” The consultants differed on the type of leadership most highly in demand, mentioning “inspirational leadership,” “leadership in a non-authoritarian manner that works with today’s executive talent,” “take-charge” leadership, “leadership balanced with authenticity, respect for others, and trust building,” and “strategic leadership.” Ethical leadership was also mentioned. Some consultants observed that the type of leadership sought depends on a company’s specific needs. “Visionary leadership is frequently mentioned when a company is on a new path, adopting a new strategy, or at a tipping point in its growth,” one respondent noted. Another said, “Driving an organization or function to a higher level of performance, efficiency, or growth requires a ‘take-charge’ leadership.” One consultant predicted that firms in 2020 will seek the “same [attributes as in 2010] but with an even greater appreciation for the intangibles of leadership and [for experience] having led a business through tough times.”

Strategic thinking and execution. “Strategic foresight”— the ability to think strategically, often on a global basis—was also frequently cited. One consultant stressed the ability to “set the strategic direction” for the organization; another equated strategic thinking with “integrative leadership.” Others emphasized that strategic thinking also calls for the ability to execute a vision, which one respondent called “operating savvy” and another defined as “a high standard in execution.” One consultant pointed out that strategic thinking is a relatively new requirement for many functional C-level executives, and another noted that the surge in attention to strategic thinking occurred in the decade 2000–2010. [BA1]

Technical and technology skills. The third most frequently cited requirement for C-level executives was technical skills—specifically, deep familiarity with the particular body of knowledge under their auspices, such as law, financials, or technology. Many respondents stressed technology skills and technical literacy. “A C-level executive needs to understand how technology is impacting their organization and how to exploit technology,” one respondent asserted. Others stressed financial acumen and “industry-specific content knowledge.” In contrast to popular wisdom, many technical skills are not declining but increasing in importance.

Team- and relationship-building. Many consultants emphasized team-related skills: building and leading teams and working collegially. “A world-class leader must be able to hire and develop an exceptionally strong leadership team—he/she cannot succeed as a brilliant one-person player,” one asserted. Another said that today’s executive must be “more interested and skilled in developing his/her team, less self-oriented.” Executives no longer sit behind closed doors,” one consultant said; instead they must be “team-oriented, capable of multitasking continuously, leading without rank, resisting stress, ensuring that subordinates do not suffer burnout—and do all of this with a big smile in an open-plan office.” One consultant characterized the entire company as a team and described the executive’s job as “leading and developing the company’s team, from the leadership down to the ‘troops.’”

Communication and presentation. Collectively, the consultants said the ideal C-suite candidate possesses the power of persuasion and excellent presentation skills—which one consultant called “the intellectual capability to interact with a wide variety of stakeholders.” This is a tall order because there are many more stakeholders now than before. Speaking convincingly to the concerns of varied audiences— knowledgeable and unsophisticated, internal and external, friendly and skeptical—calls for mental deftness and stylistic versatility. Some consultants emphasized that a strong candidate should be “board-ready”; others emphasized the ability to “influence the direction of a business and the front office” and to achieve “organizational buy-in.” And C-level executives must also be adept at communicating externally. “Presentation skills have become key to success,” one consultant said, “and will continue to be of increasing importance in the future, as the media, governments, employees, shareholders and regulators take an ever-increasing interest in what occurs in big business.” Another warned that executives need to be “good at making presentations in front of a ‘tough audience.’” Finally, C-level executives must be adept in receiving and synthesizing information.

Change-management. Virtually unacknowledged and underappreciated until quite recently, change-management skills are in growing demand. Consultants noted rising demand for an executive who is a “change driver,” able to “lead a transformation/change agenda” and capable of “driving transformational change.”One thoughtful consultant said that, as a job specification, change management typically has less to do with driving drastic firm-wide change than with being at ease with constant flux. “This requires a ‘change-agent’ executive,” he noted, “motivated by a continuous-improvement mindset, a sense of always upgrading organizations, building better processes and systems, improving commercial relationships, increasing market share, and developing leadership.” Another consultant noted that a firm seeking an executive who can engineer change often opts for an external candidate on the grounds that an external hire can bring “a new skill set that can lead to significant change and growth.”

Integrity. Although not skills per se, integrity and a reputation for ethical conduct are highly valued, according to the consultants we surveyed. One said that hiring companies want “unquestioned ethics.” Another remarked that ethical conduct was not explicitly sought in the past but would be front and center going forward: “Personal integrity and ethical behavior . . . are far more important now because of the speed of communication.” Another said that “organizations are more attuned to the ‘acceptability’ of senior hires, be it to regulators, investors or governments.”

We also asked the executive-search consultants how the most highly prized C-level skills have changed over time and what further change they foresee. The first clear theme that emerged is the importance of a global outlook and meaningful international experience. Already the foremost emerging skill over the past decade, a global orientation is apt to become even more dominant going forward.

Another striking theme was the demise of the star culture. Being a team player—working well with others—matters more and is expected to grow in importance. Team skills and change-management skills tied for second place among those considered crucial today but largely ignored ten years ago. One consultant shared a telling anecdote: “Recently I was called to find the new CEO of a local branch of an international company. The former CEO was fired because his management team decided he was too bossy and did not allow them opportunities for growth. They brought these concerns to the top level of the company, and the decision was to replace him.”

Many consultants said that technical skills—once the prime goal of executive searches—are still important but have become merely a baseline requirement. Because the repertoire of obligatory executive skills has grown in scope, some said, both hard and soft requirements have expanded accordingly. Executives who neglect their technical skills might be passed over. In fast changing global economy, dated technical skills can hamper resource-allocation and strategic decisions.

What skills do you think executives need to be successful now and what skills will they need in 2020? What are you doing to be ready to be hired in ten years? We would love to hear; please share your ideas with us.

———————-

Methodology

To answer these questions, we surveyed several dozen top senior search consultants at a top global executive-placement firm in 2010. As a group, they were 57% male and 43% female. They represented a wide range of industries, including industrial (28%), financial (19%), consumer (13%), technology (11%), corporate (6%), functional practice (6%), education/social enterprise (4%), and life sciences (4%). These senior search consultants worked in 19 different countries from every region of the world, including North American (34%), Europe (28%), Asia/India (26%), Australia/New Zealand (6%), Africa (4%) and South America (2%).

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Why Good Managers Are So Rare

Loose Ties Are Abundant, but Risky, at the Top

Developing Mindful Leaders for the C-Suite

Meet the Fastest Rising Executive in the Fortune 100

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers