Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1447

March 27, 2014

Are You the “Real You” in the Office?

Harvard’s Robert Kegan on companies that do really personal development. For more, read the article, Making Business Personal.

Google’s Scientific Approach to Work-Life Balance (and Much More)

More than 65 years ago in Massachusetts, doctors began a longitudinal study that would transform our understanding of heart disease. The Framingham Heart Study, which started with more than 5,000 people and continues to this day, has become a data source for not just heart disease, but also for insights about weight loss (adjusting your social network helps people lose weight), genetics (inheritance patterns), and even happiness (living within a mile of a happy friend has a 25% chance of making you happier).

Upon reading about the study, I wondered if the idea of such long-term research could be attempted in another field that touches all of us: work. After more than a decade in People Operations, I believe that the experience of work can be — should be — so much better. We all have our opinions and case studies, but there is precious little scientific certainty around how to build great work environments, cultivate high performing teams, maximize productivity, or enhance happiness.

Inspired by the Framingham research, our People Innovation Lab developed gDNA, Google’s first major long-term study aimed at understanding work. Under the leadership of PhD Googlers Brian Welle and Jennifer Kurkoski, we’re two years into what we hope will be a century-long study. We’re already getting glimpses of the smart decisions today that can have profound impact on our future selves, and the future of work overall.

This isn’t your typical employee survey. Since we know that the way each employee experiences work is determined by innate characteristics (nature) and his or her surroundings (nurture), the gDNA survey collects information about both. Here’s how it works: a randomly selected and representative group of over 4,000 Googlers completes two in-depth surveys each year. The survey itself is built on scientifically validated questions and measurement scales. We ask about traits that are static, like personality; characteristics that change, like attitudes about culture, work projects, and co-workers; and how Googlers fit into the web of relationships around all of us. We then consider how all these factors interact, as well as with biographical characteristics like tenure, role and performance. Critically, participation is optional and confidential.

What do we hope to learn? In the short-term, how to improve wellbeing, how to cultivate better leaders, how to keep Googlers engaged for longer periods of time, how happiness impacts work and how work impacts happiness.

For example, much has been written about balancing work and personal life. But the idea that there is a perfect balance is a red herring. For most people work and life are practically inseparable. Technology makes us accessible at all hours (sorry about that!), and friendships and personal connections have always been a part of work.

Our first rounds of gDNA have revealed that only 31% of people are able to break free of this burden of blurring. We call them “Segmentors.” They draw a psychological line between work stress and the rest of their lives, and without a care for looming deadlines and floods of emails can fall gently asleep each night. Segmentors reported preferences like “I don’t like to have to think about work while I am at home.”

For “Integrators”, by contrast, work looms constantly in the background. They not only find themselves checking email all evening, but pressing refresh on gmail again and again to see if new work has come in. (To be precise, people fall on a continuum across these dimensions, so I’m simplifying a bit.)

Of these Integrators (69% of people), more than half want to get better at segmenting. This group expressed preferences like “It is often difficult to tell where my work life ends and my non-work life begins.”

The fact that such a large percentage of Google’s employees wish they could separate from work but aren’t able to is troubling, but also speaks to the potential for this kind of research. The existence of this group suggests that it is not enough to wish yourself into being a Segmentor. But by identifying where employees fall on this spectrum, we hope that Google can design environments that make it easier for employees to disconnect. Our Dublin office, for example, ran a program called “Dublin Goes Dark” which asked people to drop off their devices at the front desk before going home for the night. Googlers reported blissful, stressless evenings. Similarly, nudging Segmentors to ignore off-hour emails and use all their vacation days might improve well-being over time. The long-term nature of these questions suggests that the real value of gDNA will take years to realize.

Beyond work-life balance there are any number of fascinating puzzles that we hope this longitudinal approach can help solve. For a given type of problem, what diverse characteristics should a team possess to have the best chance of solving it? What are the biggest influencers of a satisfying and productive work experience? How can peak performance be sustained over decades? How are ideas born and how do they die? How do we maximize happiness and productivity at the same time?

The best part is that, just like the Framingham researchers, we don’t yet know what we’ll discover. They worked for 20 years before trends began to emerge, and today those findings are among the clearest risk factors of heart disease we’ve got–think cigarette smoking, lack of exercise, and obesity. gDNA is still in its infancy, and is inherently limited because we’re only including current and former Googlers. But already Googlers tell us that learning more about themselves has been eye-opening. In the future, we hope to find ways to share our data and findings more broadly. It’s thrilling not just to reimagine work at Google but to get to work with academics and other partners who can bring new perspectives to help us think beyond our ranks.

People Science needs to be adaptive. By analyzing behaviors, attitudes, personality traits and perception over time, we aim to identify the biggest influencers of a satisfying and productive work experience. The data from gDNA allows us to flex our people practices in anticipation of our peoples’ needs.

We have great luxuries at Google in our supportive leadership, curious employees who trust our efforts, and the resources to have our People Innovation Lab. But for any organization, there are four steps you can take to start your own exploration and move from hunches to science:

1. Ask yourself what your most pressing people issues are. Retention? Innovation? Efficiency? Or better yet, ask your people what those issues are.

2. Survey your people about how they think they are doing on those most pressing issues, and what they would do to improve.

3. Tell your people what you learned. If it’s about the company, they’ll have ideas to improve it. If it’s about themselves – like our gDNA work – they’ll be grateful.

4. Run experiments based on what your people tell you. Take two groups with the same problem, and try to fix it for just one. Most companies roll out change after change, and never really know why something worked, or if it did at all. By comparing between the groups, you’ll be able to learn what works and what doesn’t.

And in 100 years we can all compare notes.

Where to Find Authentic Entrepreneurs

I still remember when Steve Jobs was featured in business school case studies as an example of bad leadership style. At the time, Apple was a less-than-successful computer company, and Steve – ever the loner – had moved on to create Next, another less-than-successful one. When things go poorly for a nonconformist, how easy it is to call them the fool. But on those rare occasions when the loner gets it right – see Jobs a few years later when he returned to Apple – he does so in a big way. Nothing pays off so well as a nonconformist strategy that wins.

Many people come to the Silicon Valley in search of nonconformist entrepreneurs, looking for the next big thing. But here’s the problem: here, entrepreneurship is the norm. The way to conform in the Silicon Valley is to act like an entrepreneur. I’ve often been told by spectacularly intelligent Stanford students, sheepishly, that they have accepted a well-paying job at a big established company. That such great news is delivered with embarrassment says something about the culture of the Silicon Valley. In places where entrepreneurship is all the rage, you can’t tell the loners from the poseurs. It makes it really hard to figure out who really means it.

To find a nonconformist entrepreneur, we should look to places where entrepreneurship is unpopular. Consider Tokyo. A company’s status matters a lot in most countries, but this is especially true in Japan. So it was shocking when the “Purinto Kurabu” (in English, “Print Club”) appeared all over Tokyo back in the 1990s.

Japanese teens lined up for blocks to get into one of these booths for a picture with their friends, which would then come out on a sticker. Ultimately, this little device proliferated worldwide, and made a lot of money along the way. But unlike most Japanese innovations, it did not come from a big established firm. Instead, it came from a start-up company, “Atlus,” formed when Naoya Harano struck out on his own. His little company was creating some of the earliest fantasy-based video games, such as “Megami Tensei” (in English, “Transformation of the Goddess”) and had a cult following in Japan.

But these games did not pay the bills. Harano, desperate and intelligent (a great combination), made money any way he could – distributing billiard tables to gaming rooms, setting up karaoke machines in empty container vehicles around Tokyo, and the like. The consummate loner, Harano would likely have stayed off our radar screen, except that one day his unpredictable behavior led to a fantastically successful product. In fact, the idea for the product itself came from a female secretary at Altus. This never would have happened at one of the huge, established Japanese conglomerates, where a new idea from a low-status female worker would have had no chance. But in the hands of a nonconformist entrepreneur, the idea saw the light of day.

Other examples abound once you look for them. In the UAE, you might be surprised to find twofour54, an entrepreneurial media hub in Abu Dhabi run by Ms. Noura Al Kaabi. Coming out of Peru, you’ll find Kola Real, formed during a coup d’état in 1988, not exactly an ideal environment for business incubation. Or, in Kamchatka, you’ll find ecotourism ventures by Wild Salmon River Expeditions, initiated by an alliance between a former American military officer and his Russian associates. Name your own unusual circumstance. Where entrepreneurship is least expected, only the authentic entrepreneurs show up.

You’d think that professionals might be better at turning up these high-risk, high-reward authentic entrepreneurs, but they’re not. Professor Elizabeth Pontikes of the University of Chicago and I examined thousands of software firms over more than a decade. Companies and venture capitalists chase hot markets. Entries into markets triggered more entries, and markets that saw companies fleeing went cold. Venture capital magnified this boom and bust cycle: firms were especially likely to enter markets that had recently attracted VC funding, and VCs moved into markets that had recently attracted VC funding (especially those that had attracted attention from large, high-status VCs). Organizations that entered when VC fundings were booming were increasingly likely to fail, and those financed in a VC funding boom were unlikely to make it to an IPO. By contrast, those (fewer) firms that entered markets during bad times were then increasingly likely to prevail.

Nonconformist thinking has the best potential for genius. Those who follow the herd may or may not be right, but for sure they are predictable. The loners, those willing to go against the consensus, are anything but predictable. They may well be wrong, in which case they look the fool. But when the loners are right, we think of them – later, with hindsight – as geniuses. No wonder we resonate to Robert Frost: “I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.”

An earlier version of this post appear at BarnettTalks.

The Case for Team Diversity Gets Even Better

We know intuitively that innovation goals are well served by cross-functional “SWAT” teams that are diverse in their membership. As Andy Zynga argued in an earlier post, diversity is a means to overcome the cognitive biases that prevent people from seeing new approaches or engaging them when found. But while this seems only logical, is there empirical evidence to support it? When such diversity is enforced can we expect it to produce results? How do we know “more is better”?

Stanford professor Lee Fleming and his colleagues have been working on these questions by looking for patterns in the teams behind patents. They find that higher-valued industrial innovation (by its nature also riskier) is more likely to arise when diverse teams are assembled of people with deep subject matter expertise in their areas. Other interesting findings in Fleming’s body of work include the observation of a bimodal distribution of outcomes for diverse teams (that is, a relatively high rate of failure and high rate of big successes, with not much middle ground); and the discovery that different kinds of communications networks foster different levels of diffusion of innovation. Fleming focuses on cross-pollination in the context of “big D” Development, which often involves recombination of existing knowledge to serve commercial goals.

Along similar lines, Ben Jones and colleagues at the Kellogg Business School of Northwestern University published a paper in Science last year focusing on diversity in the production of new knowledge, as reflected in the research literature. Looking for patterns across some 17.9 million papers indexed in Thomson Reuter’s Web of Science, they demonstrated that the most influential papers (most highly cited) were those that exhibited an intrusion of interdisciplinary information. They also found that groups were more likely to foster these intrusions than solo researchers. This is entirely consistent with Fleming’s findings for industry, and his attempts to dispel some of the mythology around lone inventors. (One difference in the studies is that, thus far, Jones hasn’t observed the bimodal distribution that Fleming does; there is apparently no cluster of papers with abnormally low citations which also feature intrusions of outside knowledge.)

Taken together, the studies led by Fleming and Jones make a good case for assembling that SWAT team that can bring multiple disciplinary perspectives to bear on a problem. It isn’t always obvious how to do so, but we at NineSigma can point to an instructive example at AkzoNobel. AkzoNobel is a multi-national, multi-divisional manufacturer and distributor of coatings systems, or more simply put, paint. But paint is really not as simple as just paint; for example, coatings for automotive applications are very different from decorative finishes. Among AkzoNobel’s divisions are more and less conventional manufacturers of chemicals and polymers. Having grown by acquisition, the company has the typical silos, with organizational and geographic boundaries inhibiting the diffusion of knowledge.

AkzoNobel was already breaking down external barriers by engaging in open innovation, inviting solution ideas from outside the company. Management wanted to break down the internal barriers, too. The solution was to implement essentially the same Request for Proposal process inside the organization, broadly training large numbers of technical staff about the process, and more intensively training a core group of “Internal Program Managers” to provide the coaching and guidance required for a well-specified search.

Two years after that decision, it’s clear, first of all, that the system is working. Individuals with challenging problems are now able to reach out across the organization and assemble their own ad-hoc SWAT teams. As you might expect, tracking of system usage shows some groups adopting the new capability more aggressively than others, but overall, people have proved eager to tap into a system that gives them rapid access to colleagues in other divisions and countries. There is also solid evidence of input solicited from other divisions reenergizing the idea pools feeding into many R&D projects. Measurement of the success of the effort isn’t an exercise in just counting communications; the focus is on real problems being solved and new opportunities being identified.

Large-scale results from scholars like Fleming and Jones are valuable confirmation that, when teams are diverse, meaningful innovation is more likely to happen. AkzoNobel’s experience shows that a management team can put a system in place that makes assembling such teams the norm. It’s what we’ve suspected for a long time – but it’s great to have solid evidence.

Leaders Can No Longer Afford to Downplay Procurement

If you were asked to identify the most strategic and valued unit in your corporation, the procurement department would probably not come to mind. The term procurement itself has a very administrative connotation: It’s associated with buying ‘stuff’ for the lowest prices possible.

Today’s corporations are directing more and more of their budgets toward a complex web of global specialist providers and suppliers to help deliver on their businesses’ core strategies. A recently released global study of nearly 2,000 publicly traded companies found that 69.9% of corporate revenue is directed toward externalized, supplier-driven costs. In the last three years alone, companies have increased their external spend as a percentage of revenue by nearly 4%.

As a result, the role of procurement is magnified. Or, at least, it should be magnified. Suppliers must now be viewed as an extension of the company. Like the internal workforce, they must be incentivized, coached, sanctioned, and rewarded to help achieve corporate objectives.

However, procurement doesn’t register on the C-suite’s radar in a manner proportionate to its growing importance within the organization, and most procurement departments are neither ready nor empowered to take on their new responsibilities. Here are some of the reasons for this:

An unproductive fixation on cutting costs

Businesses want to increase profits to grow shareholder value, so procurement incessantly portrays savings as profit improvements. At best, this is naive and, at worst, disingenuous. Improvements to shareholder value come from delivering the corporation’s objectives, not from decreasing spending. And too often, savings just represent corrections of past failures in managing supplier relationships. There are some corporations whose objective is to have the lowest possible cost base as the primary source of competitive advantage, but even here procurement still disappoints, as it seldom owns the budgets and therefore has a much smaller impact on profits than imagined.

Organizational isolation

Procurement teams are often disconnected from the functions they serve and the markets they engage. Too often, they are not fluent in the nuances of the business and therefore lack the expertise and authority to challenge or influence spending decisions. This often frustrates sales and the revenue-generating front lines, further isolating procurement.

Glacial processes

Procurement teams tend to rely on processes that are far too slow to support the business’s needs. Procurement’s response to almost any problem is to run a sourcing exercise and issue a tender, which could take six to eight weeks. That’s just not acceptable in today’s fast-moving and interconnected environment.

Acting without inquiry

Procurement fails to ask the most basic of questions: Why? In most organizations today, procurement people are not programmed, encouraged, or incentivized to do much other than review vendors and negotiate terms, even when there might be a better way of serving the business’s need. Many lack the training and skills to thoughtfully analyze a sourcing request and their aforementioned isolation makes it nearly impossible to truly understand business priorities. Instead, requests are taken at face value without second thought.

So, what can be done to improve procurement? How can we resolve a function that is increasingly marginalized, despite its growing importance to the firm?

The answers lie in four fundamental areas that need to be addressed and resolved by C-level leaders:

First, leaders should reassess and clearly define the role of procurement in the company philosophy. Is it a process-oriented, savings-obsessed function? Or does it focus on customer service and helping the business achieve its strategy?

Second, they should change the way procurement is measured, connecting its objectives to those of the budget holders it is there to serve. Leaders should consider what the business is trying to achieve and design metrics around areas such as innovation, stakeholder experience, risk mitigation, improving ways of working, and spending wisely rather than less.

Third, leaders should determine whether the current cast of procurement executives has the required skills and abilities. A very broad range is needed – from consultants, with skills like rapport building, influencing, and dealing with difficult stakeholders, to analysts, process mappers, researchers, negotiators, change managers, paralegals, contract managers, project managers, and so on. Deep expertise is critical in each area. If the requisite skills are absent, the company needs a plan for acquiring them through training, recruitment, or partnerships with third parties – or all three.

Finally, leaders must give procurement teams incentives to create a welcoming atmosphere for suppliers. If procurement is operating effectively, suppliers should be beating down the door to get their goods and services sold into the organization. They should be treated as a driving force for innovation and viewed as critical partners in the company’s success.

To Improve Collaboration, Try an Olive Branch on Steroids

With the exception of “dyed-in-the-wool” unforgiving types (you know, the people who seem to delight in ruining family holiday dinners), one of the things nearly all of us are defenseless against is a sincere, earnest, unsolicited apology.

Despite its power, there are not a small number of people in this world who have never received one — and an equally sizable number of people who have never felt they owed one to someone. And yet for the majority of people, it’s disarming and intriguing enough to lower their guard to hear what the apologizer has to say.

If you’re unsure of the value in delivering a sincere, earnest, unsolicited apology, you need go no further than the neurology of mirror neurons. Mirror neurons appear to help us with learning and empathy. But they can also have a negative impact, such as when criticism triggers defensiveness (i.e. a reciprocal criticism from the criticized) and bared teeth trigger reciprocally bared teeth. In the case of a sincere, earnest, unsolicited apology, receptiveness begets more openness. Still too soft? You need look no further than conflicts you have successfully resolved at home with your spouses, children or parents… unless of course you truly believe that your “my way or the highway” approach to life has served you well.

So, I can’t guarantee that it will work, but if there is someone you work with that is not cooperating and with whom you would like to improve cooperation, it might be worth your trying. The sincere, earnest, unsolicited apology consists of five steps:

Select the person with whom you would like to improve cooperation with and communicate to them (probably best to do in person at not by paper trail leaving email), “Might there be a time when we can talk for a few minutes in person or by phone, because I just realized that I owe you an apology?” Hopefully their curiosity will cause them to agree.

When you meet say to them, “Would you agree that we have come to different conclusions on a number of situations?” Hopefully they will agree with that statement — but if they hesitate, simply proceed directly to the next step:

“If that’s so, I owe you an apology because I have never taken the time or made the effort to understand how you came to came to the conclusions you have.” Then wait to see what they say. In all likelihood they will say nothing because they’ll be too busy feeling a little disarmed and not knowing what to think.

Wait a few moments and then say, “And furthermore I owe you another apology for something that I am not proud of. And that is that I never even wanted to understand your point of view, because I was so focused on pushing through my agenda. That was wrong and I am sorry.” Owning up to and taking responsibility for negative thoughts and feelings they have towards you is further disarming.

Then say, “And if you are willing to give me another chance, I would like to fix that starting now.”

This may not always work, but it has a good chance of being accepted. If it is, but seem dumbfounded or are looking for you to start the ball rolling, do so by saying, “So please tell me how you came to think about x, y and z the way you do.”

As they begin to explain how they have come to develop their point of view, employ conversation deepeners to help them open up ever more deeply. Conversation deepeners including saying thinks like, “Say more about such and such” (where “such and such” is any statement they make that has an emotional charge or uses hyperbole)” or “Really,” (with a tone that communicates interest and understanding on your part, not skepticism) or even just “Hmmm.”

Keep listening until you really do understand how and why they think the way they do. You can communicate that by saying such things as, “Wow, that really explains a lot” or “I can see why you think and believe what you do.”

After you have reached that point you will often have the opportunity to say, “You don’t have to, but would you want to hear about what I think and believe and how I came to my conclusion about those matters?” Hopefully they will mirror the receptiveness you’ve just shown. But if they say no, you might follow up with something like, “I will definitely respect that, however we are both expected by each of our [departments/groups/bosses] to work together and achieve a result that will satisfy them and help our respective [group/company]. So then, how do you suggest we proceed, if we can now agree that neither of us wants to do something that jeopardizes either of our positions in our respective companies?” By following these steps you are setting the other person and you up to formulate a solution to the problem each of you are trying to solve in your particular job in your company.

And that is not merely cooperation. It’s taking a big step toward collaboration and that is where you both begin to take action.

How Corporate Investors Can Improve Their Odds

When investing in new growth businesses, corporate leaders are commonly advised to behave more like venture capitalists. VCs, they’re told, take more of a long-term approach, have a greater degree of risk tolerance, and parcel out their funds in stages to mitigate risk.

All of this is right, as far as it goes. But having spent the past five years straddling between our consulting business (which advises large companies) and our venture investment arm (which provides seed investment to entrepreneurs), I now believe there is a more fundamental philosophical difference that corporate leaders need to adopt as well, if they’re serious about creating dynamic new growth businesses that stretch the boundaries of their current business models.

The philosophical divide is this: When VCs invest in an early-stage start-up, they recognize that odds are, the company will fail. When large companies invest in a nascent idea, they will only do so if they see convincing proof that they will generate an appropriate return on their investment. But that seemingly safer approach actually pretty much guarantees corporate investors poor returns on their new growth investments.

Why?

It’s not that VCs invest in businesses they think are bad. They just know the odds are stacked against any particular start-up. So when they invest, they look for a business with the potential to hit it big (to cover the inevitable losses), and they take steps to learn quickly whether that possibility is remote or realistic. The operative question for them is, not “How confident am I that this investment will yield a positive return?” but “How much can we afford to lose on a given investment?”

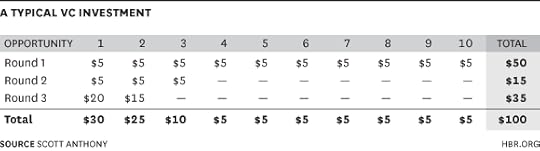

So, a VC might spread her $100 of investment capital across 10 companies in the following way:

Every company starts with $5. Six – which show their lack of promise early on — never receive any follow-on funds. One – possibly more promising — receives one more round of funding. Three companies end up taking 60% of all investment dollars.

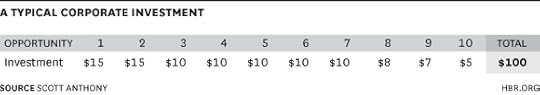

By contrast, for corporate innovators each idea needs to carry its own weight. Ideas with positive discounted cash flows get investment. Those that don’t, don’t. Big bets don’t make it through the every-idea-has-to-be-a-winner screen because it’s very hard to create reliable, detailed financial projections for the types of uncertain ideas that have the promise of big returns. So, the corporate investor might spread his investment as follows:

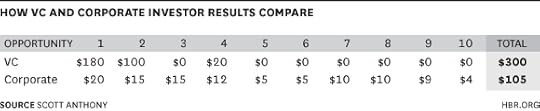

This looks like a safe, prudent portfolio. But how do the investments actually pan out? Results might look like this:

Every idea the corporate investor backed produced something. Five produced positive returns, two broke even, and three lost a little, but not a catastrophic, amount of money.

Trying to make everything a winner led to two hidden traps. First, as in this example, it’s rare that every corporate bet pays off, even when betting conservatively. And yet no provision was made to cover the cost of the inevitable failures. It’s probably true that corporate investors suffer fewer strike-outs than VCs. It’s hard to get good data on innovation success rates, but most corporate leaders will report that even close-to-the-core efforts fail to deliver on their promise at least a third of the time. And of course the more the company pushes the edges of today’s business, the lower those odds sink.

Second, what happens if there is an idea in the portfolio with breakthrough potential? Since the venture capitalist made her investment in smaller increments, she was eventually able to double down on the ideas with substantial potential. The every-idea-must-be-a-winner investor locked all of his resources into smaller projects, none of which was ever going to yield a substantial payback.

The lesson here is clear. If you’re investing in new growth businesses inside a company and want to adopt a VC mind-set, start by assuming any given investment is not going to pan out. Invest a little to test that assumption. Measure the progress of the teams running the projects not by how quickly they can produce commercial results but by how quickly they can provide vital information (evidence of unit profitability, customer interest in the idea, technological feasibility, regulatory clearance, and so on) to figure out if they will eventually produce sizable commercial results. Regard just as valuable evidence that a project won’t pan out as evidence that it will. Expand investment in the winners, and cut off the losers as quickly as possible.

That’s how you invest in growth.

Could You Come Up with $2,000 in 30 Days?

A substantial fraction of seemingly middle-class Americans are “financially fragile” in the sense that they’d be unable to come up with $2,000—the cost of a major car repair or legal or medical expense—within 30 days, says a team led by Annamaria Lusardi of George Washington University. Specifically, nearly half of Americans surveyed in 2009 reported that they “probably” would be unable to come up with that sum, and one-quarter of the total were “certain” they couldn’t. Those in the “probably” group would seek to raise funds by doing such things as tapping family and friends, increasing their work hours, or selling their possessions.

Midsize Companies Must Prioritize Ruthlessly

The world is littered with the hollowed-out shells of firms that tried to do too much and spent too big trying to grow too fast. Many of those firms were midsize companies; they didn’t have the resources of the big firms to sustain setbacks, nor were they scrappy like most small companies, making do with the resources they had.

I have interviewed more than 100 leaders of midsize companies in the last three years and been a CEO coach to several dozen others. Before that, from 1996 to 2006, I was the CEO of a firm that grew to the small end of midsize (Bentley Publishing Group). I have seen again and again the dysfunctions that derail growth of midsize companies – maladies that are not nearly as harmful to smaller and larger companies. One of these: letting time slip-side away.

While poor time management hurts large and small firms as well, it’s especially pernicious at midsize companies. The reason is that they must still move quickly to fend off smaller competitors but must tackle big projects to support growth, deliver enterprise-class service to large customers, and compete with large competitors. All this on a midsized company budget. Every second counts.

Being neither big nor small forces midsize firms to prioritize ruthlessly. To survive downturns and stay focused during upturns, these firms must plan their high-priority initiatives meticulously. And as they do, they need to understand that time is never on their side.

Here’s the story of how one midsize company changed its sense of time.

Despite many successes and the best of intentions, Pennsylvania-based Goddard Systems Inc., national franchisor of The Goddard School preschool system, missed deadline after deadline in 2007 rewriting its franchisee training manual. Franchisors use this training manual as a fundamental tool for capturing best practices and disseminating them efficiently. Over 17 years, Goddard had grown to 200 locations and its old manual was out-of-date, calling for too much one-on-one training for new franchisees and employees. To sustain growth, Goddard had to rewrite the training manual.

But for Goddard’s top management, a new manual was not perceived as critical to keeping their 200 schools operating well. Since they considered other projects to be far more important, the manual wasn’t getting done. When new leader (and now CEO), Joe Schumacher, joined the company in 2007, he recognized the fundamental problem: the Goddard team didn’t appreciate time.

Schumacher made rewriting the training manual a real priority, knowing that rapid expansion was just around the corner. If Goddard didn’t have the new manual, training and new-school performance would suffer. Schumacher assigned the training manual to one of his direct reports: it got done.

In addition, Schumacher required his team to compile strong business cases for all their projects. The process helped everyone differentiate high-priority from low-priority initiatives, and it forced senior managers to identify the resources their projects would require.

Today, the firm has grown to nearly 400 locations, almost double the number from when Schumacher arrived. The management team is continually trained on project management techniques, which Goddard now recognizes as fundamental executive skills.

Time, not money, is the most important resource for midsized firms. In order to create a culture which treats time as a valuable commodity in short supply, leadership must believethis. All the project management in the world will go for naught if the CEO disrespects deadlines. Such behavior must become unacceptable at every level. There are three steps executives at midsize companies can take to get everyone to respect time as a resource.

1. Ruthlessly cut projects until only a handful of critical ones remain. Often midsized companies have the resources to manage only one key initiative at a time. Here’s an awful truth that CEOs of midsized companies must acknowledge: Even if they’re the boss, there are limits to what they can do. Kill your pet projects. When a company tries to do too much with too few resources in too little time, projects will be late if they’re completed at all. Invariably they will be done poorly.

2. Expose the status of core projects, warts and all. The status of crucial projects must be made naked to the entire management team – especially when progress slips. In midsize companies, core projects by definition affect every department since the core of the business isn’t that big. Deadlines that are missed and tasks that run into trouble can’t be known to just a few, for two reasons. First, the people kept in the dark may not be able to execute their assigned tasks at later dates, and getting things back on track could require the senior management team’s collective ingenuity. Second, in many cases, the midsize company senior team holds most of the subject matter expertise. Not only must the project leader — under the supervision of the CEO — inform every team member about the state of each task on a detailed plan, he must also provide his opinion on the project’s progress. That lets each team member know the boss is watching and no one can hide.

3. Promote your best time-managers. CEOs and senior leaders must explain the personal rewards for critical projects executed well and on-time. Well-planned and executed initiatives ought to fuel individual career growth, as well as company growth. Managers must remind their direct reports that promotion opportunities are much greater in fast-growing companies – but that promotions only go to those team members responsible for growth. Advancement and learning are critical motivating factors in midsized firms, who often don’t have stock options (like a Fortune 500) or equity (like a start-up) to offer. But the stick is just as important as the carrot. The consequences of missing deadlines must also be career altering. The leaders of the team should be uncomfortable with the pressure; that discomfort will motivate them to avoid failure.

March 26, 2014

CEOs: Own the Crisis or It Will Own You

The terrible press for GM keeps coming. The New York Times reported this week that GM lied to grieving families about the reasons for their loved ones’ deaths and even aggressively threatened families should they sue the company. This comes on top of recent revelations that GM officials knew about the faulty and deadly ignition switch issue in the Chevy Cobalt for years before recalling the cars. All this hits only months into Mary Barra’s tenure as CEO. While GM’s crisis is dramatic and specific, the crisis and the way Barra is handling it offer a broad array of lessons and a fair dose of controversy about what good leadership looks like and how some in the media judge male and female leaders differently.

Barra has wisely opted to “own” the crisis — even though she’s only been CEO a short while and had no apparent role in the scandal. Nevertheless, she has taken on the crisis with full attention and focus, constantly facing both the media and her own employees with candor and honesty in the process. She has won well-deserved praise for her swift action and willingness to be accountable. But in an opinion piece in USA Today this week, Michael Wolff argues that Barra’s willingness to take responsibility for a crisis that was not of her making shows poor leadership and a female proclivity to seek the spotlight.

Wolff starts by criticizing Barra’s leadership in the crisis. He writes, “Barra could have personally sidestepped this. She’s only been the CEO for two months — it didn’t happen on her watch. And, anyway, CEOs assign responsibility, they don’t assume it.” By taking on this crisis, he argues, Barra defines her legacy from minute one with crisis not of her own making. It’s not clear what he believes she should have done differently, but it doesn’t stop him from writing a poor argument.

In 2010, I coauthored a study with the Center for Talent Innovation that aimed to quantify the intangibles of leadership: the ways in which individuals demonstrate their leadership and inspire others through some universal principles including gravitas, communications, and appearance. We found that leaders must demonstrate three key attributes in order to be seen as a true leader, both to their teams and to the outside world. First, they must have “grace under fire” — the ability to stay calm and coolheaded in any crisis. Indeed, this calm emerged as fundamental to leader credibility. But also, our research found that leaders must stand for and by a clear set of values which define them. Finally, they must have integrity, constantly speaking truthfully. Fundamentally, it emerged that in this day and age, crises are inevitable but leaders are made by the way they handle them.

By taking responsibility, demonstrating her values, and speaking honestly and forthrightly, Barra has shown stronger, not weaker leadership. Had she not done this, or simply blamed others as Wolff argues she should have, she would have inevitably faced withering and justified criticism. A different but recent example illustrates the point.

Chris Christie, in facing the recent scandals around the closing of the George Washington Bridge, refused to acknowledge any role or culpability and blamed a wide range of people from his staff to Port Authority officials. Ultimately, he may indeed be cleared of any wrongdoing. A detailed review he commissioned from a major law firm indicates he may not have had any direct role in the bridge closings as he has argued all along. At this point, though, it almost doesn’t matter. Christie’s passionate refusal to take any responsibility for the actions of his team was a bad miscalculation and made him look weak, self-serving, and desperate. The public has not forgiven him. His approval ratings are at an all-time low, and his national aspirations are clearly unattainable. Had Barra followed Wolff’s guidance and the Christie model, she would have permanently damaged her reputation, credibility, and legacy.

Perhaps the most misguided argument from Wolff asserts that Barra is “part of a new fashion of women running major companies who are, suspiciously, media-willing and comfortable.” In Wolff’s view, Barra speaks honestly to the media only to make herself a star. He points to both Sheryl Sandberg and Marissa Mayer as examples of women who seem to value the spotlight over company success. The reality today is that CEO personal brand is inseparable from the company’s brand and reputation. Take Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, Jamie Dimon — all leaders whose media personae are inseparable from the brands of their companies. The willingness of CEOs to build a strong and clear media presence is not female or self-serving — it’s essential. No one criticized Brady Dougan for his willingness to take responsibility for the illegal behavior of a few employees. In fact, he told employees, “While employee misconduct violated our policies, and was unknown to our executive management, we accept responsibility for and deeply regret these employees’ actions.” Dougan was right to do this, and so is Barra. Speaking with the media about it is part of her job — not some distinctively female desire to be a star.

It’s not uncommon to find that women leaders face some blatant bias and double standards in the media, but it’s worth the effort to call it out when it happens. In an era where so few women occupy top jobs, and many more are dissuaded from taking them for fear of intense scrutiny and bias, Wolff and other writers would do well to reflect more seriously on the true meaning, value, and actions of leadership before leveling criticism.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers