Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1443

April 4, 2014

GM’s Comeback as Theater

GM succeeded because America wanted it to, not because it had the ability to make safe cars. At least this is the argument put forth by Heidi Moore, who supports it with an HBS working paper by Susan Helper and Rebecca Henderson. In addition to calling out GM's failure to understand the true nature of global competition among automakers, the duo cites hubris as a critical factor: Even as GM continued to make inferior vehicles, it believed it was a good company with a proud history. "GM play-acted, magnificently, at resilience," Moore writes, with the government and the public complicit, all while the company continued to make cars that killed people. Instead of dreaming about a mythical past, GM needs to get beyond apologies and focus on the future: "Can GM actually make a car that's safe to drive?"

Working Hard for the (Very Little) Money The Myth of Working Your Way Through CollegeThe Atlantic

A few of your older relatives may have told you how they paid their way through college by bagging groceries or painting houses. But today's reality is that it would take a student 48 hours per week of minimum-wage work to pay for his or her education. According to a calculation for one university, the inflation-adjusted cost of a credit-hour is five times greater today than it was 35 years ago, when some of those relatives of yours were putting themselves through school by the sweat of their brows. In 1979, an industrious student could earn enough in a single day to pay for a credit-hour; today, paying for a credit hour takes 60 hours of minimum-wage labor. The solution, for many students, is loans loans loans, which translate into years of post-college penny-pinching or, in some cases, default. —Andy O'Connell

Wasn't that a Song in the Sixties?Citigroup Says the "Age of Renewables" Has BegunGreentech Media

The shale-gas boom in the U.S. has been a concern for low-carb (as in low-carbon) environmentalists, who worry that abundant, cheap natural gas will encourage us all to burn more carbon-polluting fuel and turn us away from sun and wind power. But a new report from Citigroup says gas's volatile, rising price is making those alternatives more attractive to the U.S. power industry. And with coal and nuclear power being seen as uncompetitive on cost, solar and wind will "continue to gain market share" into the foreseeable future, Citi analysts say. It's a trend that's aided by investors' realization that solar projects, in particular, offer low risk and a strong cash flow. There are a lot of acronyms to wade through in this Greentech Media piece, but there's a palpable excitement that a new age has begun in the world's biggest electricity market, and its name is "renewables." —Andy O'Connell

Your Car Has Feelings, Too How to Stop Worrying and Love the Robot That Drives You to WorkKellogg Insight

A robot doing the work of a human makes a lot of us nervous. But does making a self-driving car more like a person cause the rider trust it? The short answer is yes, according to lab research conducted by Kellogg School business professor Adam Waytz and colleagues. Experiment participants riding in a highly realistic driving simulator programmed to steer and brake autonomously reported trusting the vehicle more when it was given a name, gender, and human voice than when it drove in exactly the same manner, absent human attributes. What’s more, the riders trusted the person-like car more when it suffered a minor accident caused by another driver, and they felt less stressed to boot. Waytz had expected people to blame the self-driving vehicle for any accident. But people gave the anthropomorphized car the benefit of the doubt, as if it were a person. —Andrea Ovans

The Bright Side Livestrong Without LanceInc.

When Lance Armstrong was a hero, his Livestrong nonprofit raised hundreds of millions of dollars to help cancer patients and their families. After he stopped being a hero, the organization lost the support of Nike and RadioShack, revenue dropped, and 13 of its 100 employees resigned. Someone sent Livestrong a box of its iconic wristbands — cut into tiny pieces. That must have hurt. Would Livestrong ever be what it once was? Issie Lapowsky writes for Inc. that CEO Doug Ulman, himself a cancer survivor (three times, no less), has persevered, despite the sudden shrinking of the organization's prospects. Ulman sees not only a role for Livestrong, but new opportunities, as long as people can be persuaded to stop comparing it to what it was. He's doing things he wouldn't have done in the good old days, such as exploring a partnership with a medical school to design a cancer center. The organization’s future, he says, could be even better than its past. Now that’s optimism. —Andy O'Connell

BONUS BITSNotes on Social

U.S. Secretly Created 'Cuban Twitter' to Stir Unrest (AP)

When a Selfie Becomes an Endorsement (The Boston Globe)

This is What Happens When Facebook Controls the Signal, and it Defines You as the Noise (Gigaom)

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the May 2014 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the May issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Cartoon Caption Contest at the bottom of this post. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in the next magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“Focus, people! No one else sees a prancing pony?”

Michael Shaw

“I know you’re swamped, Doug, but I need you to karaoke something for me ASAP.”

John Caldwell

“Sometimes I wonder what it is exactly you’re grooming me for.”

P.C. Vey

And congratulations to our May caption contest winner, Frank Orlando of Sherborn, MA. Here’s his winning caption:

“Are you sure this will help our social media campaign?”

Cartoonist: Paula Pratt

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your own caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in the next magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for the prize, please submit your caption by April 17.

Cartoonist: Crowden Satz

What It Really Takes to Listen to Patients

Medical science has enabled our health care system to deliver outcomes that would have been impossible a generation ago, and advances in fields such as genomics and stem-cell therapy offer immense promise to further accelerate medical innovation.

One promising trend in improving overall care is the growing emphasis on incorporating voices of patients, consumers, and caregivers into the design of programs and policies. Health care is at the beginning of a dialogue with the world on evidence, outcomes, and patient well-being that will transform care.

As extraordinary as insights from the laboratory often are, better understanding the experiences of patients and health care providers can provide a roadmap for the critical last mile of medical care, where all policies, procedures, and practice converge into action.

Below, I offer some approaches drawn from my experiences working in health-care-delivery organizations, government, and industry. The principles I propose are my own and do not reflect official policies of any organizations with which I am affiliated.

We must strive to move beyond our own experiences. Those of us who work in health care inevitably refer to our own experiences with the health care system when making decisions about strategy and program design. Even at high levels of policy or strategy discussions, it is common to hear, “when I was at the doctor…” or “when my mom was sick…” And while we can gain insights from these personal encounters, it’s critical to remember that our expertise inside the field strongly informs our experience.

All leaders in health care have a level of access, familiarity, and comfort with medical care that vastly exceeds that of the average patient. Consequently, as health care providers, we have to ask ourselves this question: What stories are we not hearing? If we don’t keep ourselves honest and consider the voice of the patient not in the room, we overlook opportunities to improve care for a substantial number of people.

Michael Porter and I recognized this limitation in our work studying the organization and structure of cancer-care delivery and published a case study that aims to track the complexities of navigating the healthcare system. It tracks the experience of a patient and her family as they seek to treat her adrenocortical carcinoma, cancer of the adrenal glands.

From the patient’s perspective we see the confusion of conflicting treatment recommendations, the frustration of opaque hospital processes, and the strain of deciding on a course of action – all through the lens of a diagnosis that gave the patient just a handful of months to live.

As health care professionals, we have to consider the context of that type of patient experience: a person struggling with a dauntingly complex system while facing a heart-wrenching turn of events.

Get authentic patient voices in the room. To lead change in health care, organizations must get in the room the voices of real patients – people whose lives are touched by our products and services.

Whether it’s legislation or strategy, the best-intentioned and most carefully considered policies will have weaknesses that are exposed only through execution. It’s no surprise that complex processes will face challenges in implementation. But by integrating patient voice early and often, those roadblocks can be better understood and more quickly remedied.

At Merck, Michael Rosenblatt, the company’s chief medical officer, and I worked with colleagues to develop “patient input forums.” This initiative brings in volunteer patients who suffer from health conditions relevant to Merck’s research. The forum typically features patients interviewed by master clinicians who are their treating physicians.

Through these forums, Merck scientists can better understand disease from the patient’s perspective, ask questions about care treatment and process, and identify areas of unmet need. They see firsthand that a patient isn’t a disease with a body attached but a life into which a disease has intruded.

At a minimum, these forums provide inspirational value to people within the company who support the company’s mission of improving and saving lives. At best, these forums can be the source of new insights to drive discovery.

Embrace online communities, but know their limitations. Online communities are a powerful, emerging avenue for insight into patient sentiment about a disease or therapy. Many communities are focused on particular diseases and focus groups, offering a locus of conversation on specific topics.

There are, of course, limitations, one of which is self-selection bias. People participating in an online community around their disease are already more engaged, more informed, and more tech savvy than many others. So while leaders in the health care system integrate the (undeniably valuable) insights from these communities into decision-making processes, we have to account for these patients’ above-average sophistication and its implications for their treatment choices.

Remember the other influences of patient health. As impactful as the increasing focus on patient voice can be, it’s critical for organizations to consider the other influencers of a patient’s health that the patient himself might take for granted. Family members, cultural traditions, stress levels, sleep habits, and numerous other lifestyle factors impact health but are often considered “just how things are.”

As patient perspective is better integrated into health care decision-making at all levels, the health care industry has an opportunity to expand the conversation to include everyday factors that collectively have a meaningful impact on health.

Overcome the risks – they’re usually worth the benefits. Because protecting patient privacy is so important in healthcare, integrating patient voice is not as simple as one might expect. Meeting the regulatory needs of any health care organization takes planning, flexibility, and cooperation across teams.

Through engaging the patient voice, we have a powerful tool to inspire and shape new solutions in health care, and there is real value in working through the associated challenges. As the health care system takes a more collaborative approach to helping patients and as patients become active participants, everyone wins.

American Firms Dream of Growth but Invest in Efficiency

After more than five years of sluggish growth, U.S. companies are finally starting to feel a bit more optimistic. The Federal Reserve is projecting GDP growth of 2.8 to 3 percent in 2014 (U.S. Economic Outlook for 2014 and Beyond, January 13, 2014, About.com), and our own research, “CEO Briefing 2014 –The Global Agenda: Competing in a Digital World,” found widespread optimism in the C-Suite about companies’ growth prospects.

What we are not seeing, however, are many signs of truly ambitious growth strategies which could result in companies putting newly restored balance sheets to work. For example, despite all the froth about how companies need to accelerate growth in emerging markets, three-quarters of the U.S. executives surveyed said they will continue to invest heavily in their home market, which is a largely mature and slow-growing economy. These executives said they are pinning their hopes for growth in the U.S. on gaining a greater share of customers’ wallets, not necessarily on expanding their base of new customers or opening up new export markets.

That leads to two interesting questions. If emerging markets are attractive, why is so much investment capital flowing to mature markets? And, if growth is mostly about gaining market share and developing new products, why is a substantial focus on investment to retain existing customers and make existing products and services more efficient?

On the efficiency topic, 87 percent of companies represented in the study plan to increase their investments in research and development – with a significant portion of this investment devoted to digital technologies such as mobile, cloud computing, analytics, social media, ecommerce, and machine-to-machine communication. Sounds good; “New investment in innovative technologies” makes a great headline for the next earnings call or annual report. But what’s underneath such headlines is fascinating: Most of the U.S. companies in the study generally view digital technologies as a way to streamline existing operations and improve customer relationships — not as an engine for growth.

In fact, 68 percent said that their investments in digital technologies are primarily focused on process efficiencies and cost reduction, while just 25 percent said such investments were geared toward helping the company reach customers. The emphasis is on greater operational efficiency – and on improving the experience for existing customers – rather than on growing sales, opening new sales channels, or creating new products or services.

U.S. companies are great at improving existing operations and thinking of new ways to apply technology to drive productivity. In a sense, this is the basis for the story of U.S. economic performance over the last 200 years. Much can be gained from increasing employees’ efficiency and keeping existing customers happy. But these investments are not the avenues to the robust growth that innovative technology offers.

Enthusiasm for digital technologies is not lacking. Indeed, U.S. executives were more likely than their global counterparts to believe cloud computing, data analytics, ecommerce, and machine-to-machine communication will be important to their businesses in the next year. And U.S. companies appear to be further ahead of their non-U.S. counterparts in applying digital technologies to their operations: 45 percent of the former and 36 percent of the latter said such technologies support at least half of their major business processes.

The real power of digital innovation, however, is in helping create and serve new markets with entirely new offerings, and that’s where U.S. companies are still waking up to the possibilities. We see two principles that U.S. business leaders should keep in mind as they contemplate investments in innovative technologies:

Don’t bring your old business model to the new digital party. Too many companies appear to be overlaying digital technologies on their existing infrastructure and business model. Banks, for example, may be increasing their volume of mobile transactions, but many do so while maintaining a costly system of branches and ATMs. “Going digital” for many companies means creating too many channels and fragmentation, at a higher cost structure, because the new costs of digital (such as new infrastructure, customer service, technology, and management) are simply layered on top of the old business model. The result is that too many businesses are making their operations more complex in order to offer convenience to customers who are paying no more than they were before. More costs, less profit, more complexity.

Look at what’s profitable, not at what’s possible. For all the talk about customer-centricity and improving the customer experience, the primary objective for most businesses is profitable growth. Giving existing customers new and delightful digital experiences makes the most sense when it is done in the context of a) lower costs; b) new cross-selling opportunities; or c) the opening up new channels to attract previously underserved markets.

As U.S. companies invest in digital technologies, the art of the possible is often the first discussion. Moving beyond productivity, efficiency, and customer satisfaction – table stakes for business operations today – they may want to consider whether digital represents an opportunity to sell new products or services, potentially reaching new markets. Some would say that is the big payout for companies as they harness what’s possible in a digital world. Let’s think carefully about rebalancing investments in digital to support growth that reaches beyond incremental efficiency gains.

Tinkering with Strategy Can Derail Midsize Companies

Many leaders of midsize companies – especially if they’re the founders – are constitutionally inclined to see new opportunities around every corner. And they love to pursue them, deadline commitments or old strategies be damned. They forget that the strategy which took them from small to midsize has already proven itself a winner. But a new vision is always more exciting to them than the present one. So they begin tinkering with their core strategy, burning up resources while their companies wander off their tried-and-true growth path.

The tales of two companies, cell phone accessories retailer Cellairis and skin care products maker Rodan + Fields, illustrate the dangers of top-level strategic tinkering.

Three friends, Taki Skouras, Joseph Brown and his twin brother Jaime Brown, launched Cellairis in Atlanta in 2000 to ride the cell phone boom. They had the epiphany that they could use cheap retail space – the carts that sit in the middle of shopping malls – to sell mobile phone accessories, mostly cases. Five years later, they had a $50 million business (including franchisees’ revenue). The future looked bright.

That’s when the tinkering began.

In 2006, they hired an experienced president to manage their rapidly growing business. The new president thought Cellairis should not only sell accessories, it should sell wireless phone service as well. Skouras, the company’s CEO, thought that sounded like a swell idea. People shopping for cell phone cases were natural customers for a wireless service provider. So the company jumped wholeheartedly into a joint venture with a reseller of wireless service, AMP’d Mobile, and opened AMP’d stores in the malls. Cellairis’ leaders didn’t think it necessary to test their new strategy. After all, it was just a slight variation on the core strategy of selling accessories. Nothing more than a tweak, they thought.

But AMP’D underpriced its services and regularly extended credit to bad-risk customers. After nine months, AMP’d filed for bankruptcy. It stiffed Cellairis and the wireless providers whose services it resold.

During those nine months, Cellairis’ leadership had been distracted from their core business. Not surprisingly, it had languished. In those nine months, the company’s revenue fell 33%. Closing the AMP’d stores cost millions. Cellairis had tinkered with its core strategy, one that had been working beautifully, and it had turned ugly. Fortunately, the founders were quick to stop tinkering and refocus on their core business of wireless accessories. System-wide revenue for 2013 was $350 million – seven times revenue for 2005.

Tinkering can kill midsize companies. Unlike a startup company, which is supposed to play with alternative strategies until the right one emerges, a midsize firm already has a strategy that is working. Sure, it must always consider whether to adjust that strategy in the face of new competition, changing customer demand, technological innovation or all three. But because midsize companies lack the resources of big companies, which can experiment with multiple new strategies and launch pilot projects, midsize firms are at risk when they divert scarce resources from their core business.

The management team at Rodan + Fields, today a $250 million skincare products company, understood this risk. That’s why the San Francisco-based company tinkered with its strategy the right way, off to the side, in a manner that would minimize damage if the experiment went wrong.

In late 2009, CEO Lori Bush was searching for a way to raise the productivity of the company’s sales force. As a direct seller like Avon, Mary Kay, and Herbalife, Rodan + Fields works with about 50,000 independent businesspeople who in turn sell its skincare products to others in their community. A direct selling company’s sales strategy is its core strategy. The reason is that unless it can continue motivating and helping salespeople succeed, a direct seller’s products won’t sell themselves. And it doesn’t have a retail channel to fall back on.

While Rodan + Fields’ makes its sales force feel like insiders, they remain a channel of independent sales professionals (whom the company calls “consultants”), some of whom hope that commissions from selling Rodan + Fields products will become their primary income. And while they love the company’s products, five years ago there was a wide disparity in sales skills.

Bush, Chairman Amnon Rodan, and adviser Oran Arazi-Gamliel decided they had two choices for the firm’s sales strategy: They could juice the sales commission plan with temporary short-term bonuses, trying to motivate their consultants to work harder. Or they could analyze the behaviors of the most successful consultants and train others on their methods. They moved on both paths at once, but with caution.

By the end of 2010, they found that incentive bonuses did have a minor impact on growth but that as soon as they were discontinued, sales dropped again. Over the same period, Bush and Arazi-Gamliel had identified top consultants in one particular city and studied their behaviors. They pinpointed a number of new consultants who were excelling, identified their behaviors and then implemented the new field development strategies with their Atlanta consultants (a tough market for the firm). The results were remarkable. Sales rose 300% in Georgia by the fall of 2010 and rose even more the following year. Since then, the company has refined and repeated the training program in many other regions of the U.S..

Rodan + Fields’ revenue growth has been breathtaking. Revenue in 2011 was $59 million. By mid-2013, the company was chugging along at a $200 million annual revenue rate.

The lesson here is to experiment carefully with variations on your successful strategy, not tinker with it in the field of play. This is a hard lesson, running counter to the improvisatory instincts of many CEOs. But they must learn it.

Once their firms have reached midsize, the CEO’s impulses must cede center stage. Scaling the business must be center stage, and strategic innovations must be tested in the wings. Creating a program to prove the viability of a significant change in the firm’s strategy ensures that the experiment won’t knock the ship off course if the idea turns out to be flawed.

In these instances, CFOs can play a valuable role: keeping the CEO (or other C-suite leaders) from yielding to the impulse to tinker. The most successful CFOs I know insist their company’s core strategy be written down. When someone begins to tinker with it, they push for clarity. They want to see exactly what resources will be required and what priorities are emphasized. As important, they want everyone to know how much time a new strategy experiment will be given to succeed.

Such discipline creates focus and forces leaders of midsize firms to determine whether a new strategy fits with the original winning plan. These simple protocols can be the difference between a midsize company that keeps its eye on the road ahead, and one that ends up in the ditch because it became distracted.

High Performers Are Covertly Victimized, Unless They’re Altruistic

In a study set in a Midwestern field office of a U.S. financial services firm, high-performing employees were more likely than average workers to report that colleagues covertly victimized them through such behaviors as sabotage, withholding resources, and avoidance, says a team led by Jaclyn M. Jensen of DePaul University. High performers’ average score on a 1-to-5 victimization-frequency scale (from “never” to “once a week or more”) was 3.37, with the greater the performance gap in the workgroup, the greater the victimization. The effect was most pronounced for high performers who were selfish and manipulative; those who were altruistic and cooperative suffered less victimization as their performance increased, the researchers say.

In China, Go for Broke or Accept that Less Is More

China is changing more rapidly than ever, but has your China strategy adapted yet? In the aftermath of the US financial crisis in 2008, companies from North America and Europe rushed into China, seeking to grow both sales and profits. However, with China’s growth slowing over the past two years, costs shooting up, the government making life difficult for multinational companies, and confusion following the reforms emanating from the Third Plenum in November 2013, some companies are heading in the opposite direction.

In early 2014, American cosmetics and skincare products powerhouse Revlon announced that it would pull out of China completely. Despite entering the world’s largest personal care products market in 1996, Revlon was able to generate just 2% of sales from China 17 years later. It therefore decided that it was time to rethink strategy. Around the same time, the French beauty company, L’Oréal, said it would stop selling its flagship brand, Garnier, in the country.

Retailers such as America’s Best Buy and Germany’s Media Markt also quit China last year while after nine years, Britain’s Tesco concluded that it was unlikely to make a dent on its own in China and entered into a joint venture with a state-owned enterprise, China Resources Enterprise. And Western Internet companies such as Yahoo!, eBay, and WhatsApp have failed to make a dent on local leaders such as Baidu, Alibaba, and WeChat, all but giving up on the Chinese market.

However, many multinational corporations cannot afford to quit China. Not only do they need the sales and profits that China — still the biggest and fastest-growing market in the world for almost anything — provides, but also, they realize that it will be tougher to re-enter the market in future. China is already the world’s fiercest battleground for global brands and more local companies are joining the fray. That leaves country managers in China with two choices, neither of which will be an easy sell at corporate headquarters (HQ) that are still looking for substantial top-line growth and above-average profits in emerging markets.

Go for Broke. One option is for multinational companies to go flat out for market leadership in China; that is, try to be either No. 1 or No. 2 in the market. The CEOs of companies that have adopted this strategy – such as KFC, PepsiCo, Kraft, Audi, BMW, and L’Oreal – spend all their time thinking about how to get bigger, faster — and don’t worry about efficiency, synergy, or cost.

The downside is that these companies may not make profits in China, at least not for a very long time, partly because of the huge investments they must make. Moreover, year after year, local rivals from both the public and private sectors have been getting better, as mentioned earlier. They have learnt to offer global quality at low prices, squeezing multinational companies’ margins and profits.

Indeed, Western multinationals that have picked this strategy may be able to pull it off only by forming alliances with rivals or acquiring them. There’s no dearth of examples: Bayer Healthcare acquired Topsun to become one of the leaders in the OTC medicines segment and Dihon in the TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicines) niche. Between 2008 and 2012, Walmart more than doubled sales by adding 100 hypermarkets to its existing 400 stores, acquiring Trustmart in 2011, and picking up a majority stake in online retailer Yihaodian in 2012. Japan’s Hitachi has struck as many as 36 alliances and joint ventures with Chinese companies such as Haier and Shanghai Electric. And Caterpillar purchased mine safety company ERA for $677 million to break into the coal industry. However, it had to take a $580-million charge after turning up book-keeping problems at an ERA subsidiary five months after the deal closed.

Accept that Less is More. Several CEOs are realizing the limits to growth in China, and have focused on boosting profitability rather than sales. Abandoning the desire to become market leaders, they have become selective. They aren’t recruiting countless sales reps or extending their distribution to hundreds of cities every year. They are gearing up to make more money with fewer resources by focusing on the most profitable products, regions, and sales teams. These companies include DSM, Bayer Material Science, Solvay, P&G, and IBM.

A smaller-and-selective strategy isn’t necessarily good news for HQs; they can no longer depend on China for growth, and must invest in other markets across the globe. Furthermore, their China teams, which have been chasing growth for years, may be on the bubble. Not all of them will have the skill sets and networks to ensure efficiency, so several companies may well have to start afresh in China.

How do companies decide which of these two approaches will work for them? One, they must evaluate their customers’ prospects to see if it’s worthwhile investing for growth. In a dynamic market like China, a review of trends is necessary every one or two years. Some sectors, such as chemicals and construction materials, are already plagued with slow growth rates; others such as consumer goods are reaching maturity so adding offices, salespeople, and distributors may boost sales but not profits.

Two, it’s important to evaluate if being the biggest kid on the block is necessary to bargain with customers. In some industries, scale lowers supply chain costs but it doesn’t provide bargaining power over buyers.

The third question is whether the Chinese market, geographically, provides synergies or turns out to be several dozen (or hundreds of) standalone markets scattered across the country. If customers don’t link across regional or municipal borders, as they do in the retail and healthcare industries, size won’t matter.

It’s tough to decide which play to pick, but companies that are unable to make up their minds will have no choice but to gallop out of China like Revlon — an unimaginable prospect until the Year of The Horse.

April 3, 2014

How Unusual CEOs Drive Value

William Thorndike, investor and author of The Outsiders, looks at some less-known but more effective executives.

How Old Are Silicon Valley’s Top Founders? Here’s the Data

Last week, The New Republic published a lengthy exploration of ageism in Silicon Valley, the idea that venture capitalists discriminate against older entrepreneurs and that start-ups discriminate against older job applicants. The central evidence was largely anecdotal: several well-worn quotes by prominent techies talking up the innovative nature of younger founders, the struggles of a “fortysomething” entrepreneur in Boston, the thesis of an angel investor betting on older, overlooked founders, and the sociological musings of a plastic surgeon who has seen more middle-aged men coming to him to look young as a way to help their career. Nonetheless, it was enough for VC Fred Wilson to concede that, “Yes tech is biased toward younger people.”

That one of the industry’s most prominent voices wouldn’t even bother to defend it against the charge may itself be the best evidence that the start-up world has a real problem with age discrimination. Nonetheless, we were curious to know just how young Silicon Valley founders really are; is the myth of the pimpled, hoodie-wearing 20-something really accurate? So we set out to find age data for start-up founders, aware of course that this data was unlikely to tip the scales in the ageism debate one way or the other.

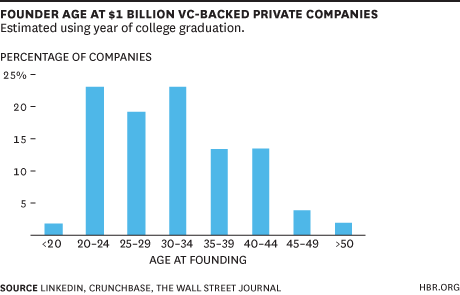

The data we collected confirms that 20-something founders are quite common among those who have built billion-dollar businesses.

The challenge with measuring age is that the data is relatively hard to find. Unless a founder has given his or her age in a magazine profile, or maintains a particularly public Facebook account, it’s hard to get age data without actually surveying entrepreneurs. But there is one clue to founder age that is often publicly available: the year they received an undergraduate degree, listed on LinkedIn. We decided to use this as a proxy for the age at which the founder was 22, under the assumption that this would provide age data that was accurate within a year or two. Unfortunately, LinkedIn does not include this data in its API, so we were limited by having to do manual research. We therefore picked a small but disproportionately influential dataset to examine: the founders of private, VC-backed companies valued at $1 billion or more.

Using The Wall Street Journal’s billion-dollar-club list, the Crunchbase API, and manually searching LinkedIn profiles for year graduated, we were able to generate a list of founders for 35 of the 41 start-ups, and to determine an approximate age for the majority of them. For those without graduation year listed, we scoured other sources and filled in reported age (from media profiles and the like) where we found it. The result was estimated age data for 52 founders, 71% of the individuals on our list. This, we believe, is a more complete picture of the age of today’s top start-up founders than what has been published to date:

The average age at founding in our dataset was just over 31, and the median was 30. Today, of course, these founders are quite a bit older, with an average age just under 39, and a median of 38.

Before trying to put this data in context, several caveats are necessary. First, because this sample includes a particularly successful (and therefore non-random) group of founders, we cannot generalize from it to conclude anything about entrepreneur age, or even VC-backed entrepreneur age, more broadly. Second, and more problematically, we were only able to uncover age proxies for 71% of the founders on our list. While the data presented here provides a richer glimpse at the age of successful founders than generalizing based on anecdote, and perhaps even better than some investors’ own pattern recognition, it nonetheless runs the risk of substantial bias. It may well be that founders who don’t list the year they graduated from college on their LinkedIn profiles are older, on average, than those who do. This possibility cautions against drawing hard and fast conclusions about even the founders of billion dollar start-ups.

So what can we say? Foremost, we can conclude that 20-something entrepreneurs are very well-represented among the most successful entrepreneurs. Even if our dataset is deeply biased in their favor, we can conclude that founders under the age of 35 represent a significant proportion of founders in the billion-dollar club, and most likely the majority. To visualize that, here is a breakdown of our data including the 21 missing founders:

Think of the data above as the minimum percentage of founders in each age bracket. If all of those whose ages we couldn’t find were 35 or older when they founded their companies, 46% of the entrepreneurs on our list would still have been under 35.

Our data suggests that founders on the billion dollar list are younger than tech entrepreneurs in general. A 2008 paper looked at a random sample of more moderately successful founders (sales in excess of $1 million and 20+ employees) and found an average and median age at founding of 39, with only 31% under 35. That contrast, between tech founders in general and founders on the billion dollar list, is confirmed by an analysis similar to our own done last year by a VC, which found an average age at founding of 34 for founders of billion dollar start-ups.

Those concerned with ageism will likely suggest that the relatively young age of founders in the billion-dollar club confirms that VCs are biased toward young entrepreneurs; skeptics of the ageism charge may see the data as confirmation that 20-something founders are disproportionately likely to build extremely valuable companies. While this data can’t settle that debate, it does confirm that many of Silicon Valley’s most successful bets have been on 20-something entrepreneurs.

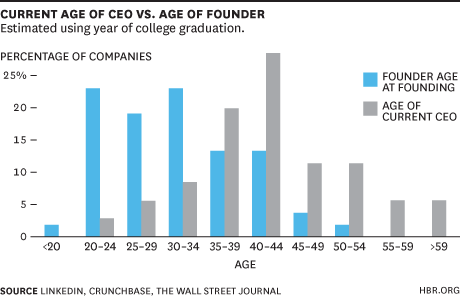

We did uncover some data to suggest an appreciation by VCs for age and experience, however. We used the same technique to look at the age of the current CEOs and Presidents of the companies on the billion-dollar list, and this group is significantly older. (Again we were able to find age proxies for just over 70% of cases, so the same caveats apply.) CEOs and Presidents are 42 years old on average, with a median of 42.

Some of the difference reflects the fact that founders grow older while running their companies, but it also suggests that in many cases they are being replaced with older, more experienced leaders.

By way of comparison, the average age of an incoming CEO to an S&P 500 company was 52.9 in 2010. Even when it comes to installing older leaders, VCs seem to prefer the young.

High Frequency Trading: Threat or Menace?

There’s a wonderful scene (one of many) in Michael Lewis’s new book, Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt, in which John Schwall, then the head of product management at RBC Capital Markets in New York, decides one day in 2011 to figure out how stock trading had evolved into a high-speed, unfair race he thought it had become.

Schwall goes into his backyard with a cigar, a chair, and an iPad, and Googles “front-running,” “Wall Street,” and “scandal.” Before long he learns that the current market landscape was to a large extent created by the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Regulation NMS, which took effect in 2007. Regulation NMS was an attempt to crack down on front-running — profiting from knowledge of customer orders to buy or sell ahead of them — by the “specialist” firms that then still controlled trading on the New York Stock Exchange. It definitely succeeded in throttling the specialists: the news this week that Goldman Sachs is hoping to find a buyer to pay $30 million for its specialist arm, which it bought for $6.5 billion just 14 years ago, is pretty conclusive evidence of that. But in the process the new rule also spawned a whole new industry of front-runners called high-frequency traders.

As Schwall looks further back into the past — he ends up spending several work days at his local public library on Staten Island — he discovers that this was just part of a long cycle going back to the 1800s:

The entire history of Wall Street was the story of scandals, it now seemed to him, linked together tail to trunk like circus elephants. Every systemic market injustice arose from some loophole in a regulation created to correct some prior injustice.

When he got back to work and described his findings to his colleagues, Schwall’s conclusion was that “U.S. financial markets had always been either corrupt or about to be corrupted.”

That’s pretty much my sense, too. In the big picture, financial middlemen exist to enable the glories of capitalism, but day-to-day they’re mainly out to separate customers from their money. This is to some extent true of any business, of course (can I interest you in an HBR subscription?), but it’s especially stark when the product being sold is financial returns and every penny taken out by intermediaries makes that product worth a little bit less.

In olden times, the middleman’s take on Wall Street was set by cartels (the stock exchanges) and more or less endorsed by government. On May 1, 1974, though, the SEC ordered the end of fixed brokerage commissions, and since then regulators in the U.S. (and elsewhere) have kept pushing for more competition, lower transaction costs, and a smaller middleman’s take. This has certainly resulted in lower stock trading commissions and, in recent years, smaller “spreads” between the prices at which brokers offer to buy or sell stocks. But the middlemen have continued to make tons and tons of money, mainly by exploiting their informational advantages over their customers.

In the case of the high-frequency traders, those informational advantages start and end with speed. While the rest of the stock market world was still operating in terms of minutes and seconds, the HFTers (led by two Chicago-based firms, hedge-fund giant Citadel and upstart GETCO, now called KCG) found a whole new world of profit in the milliseconds and microseconds between when orders were placed and filled. Thanks to their early success, and the regulatory push that had broken the NYSE/Nasdaq duopoly into a scrum of competing exchanges, the HFTers were then able to get exchanges and brokers to craft all sorts of new ways for them to make money, some of them on the face of it pretty unsavory.

But the HFTers, at least some of them, are playing the same crucial role that NYSE specialists and Nasdaq market-makers did before them — ensuring that there’s a seller for every buyer and a buyer for every seller on the stock market. What’s never answered satisfactorily in Lewis’s book is whether they’re doing a worse or better job of this than their predecessors. Lewis certainly implies that things have gotten worse in the book, and has been even more explicit in his TV experiences, but he trots out only skimpy evidence and the occasional pithy quote in support of this view. My favorite of the latter:

“There used to be this guy called Vinny who worked on the floor of the stock exchange,” said one big investor who had observed the market for a long time. “After the markets closed Vinny would get into his Cadillac and drive out to his big house in Long Island. Now there is the guy called Vladimir who gets into his jet and flies to his estate in Aspen for the weekend. I used to worry a little about Vinny. Now I worry a lot about Vladimir.”

Don’t we all? Now, I’m not saying Lewis really owes us more than that. Nobody seems to have a good handle on the economic benefits and costs of high-frequency trading. Yes, it appears to have reduced spreads, but it has also introduced new, weird kinds of price volatility — most disturbingly the flash crashes that seem to have become a regular feature of modern stock markets. It certainly has to be healthy for this new regime to be challenged, both by the heroes of the book, a group of RBCers (Schwall among them) who leave to start their own, more transparent stock exchange, and by an author like Lewis.

Especially an author like Lewis. I’ve been meaning for a while now to buy and read two critical books on HFT published in 2012, Scott Patterson’s Dark Pools and Sal Arnuk and Joseph Saluzzi’s Broken Markets — both of which Lewis gushingly endorses. But I haven’t. I bought Flash Boys right after it was published, and read it in a day. It has already unleashed at least one epic and enlightening debate on CNBC, and will surely be sparking similar discussions for months and years to come. It shouldn’t be the last word, but it wasn’t intended to be (the book was clearly a bit of rush job, albeit it a brilliantly executed one).

In all these debates, though, it’s important to remember one thing. Yes, “the stock market is rigged,” as Lewis said on 60 Minutes. But it’s always been rigged, and that hasn’t prevented it from delivering pretty impressive returns to long-run investors. Yes, we should strive toward a market that’s rigged in the least expensive, most transparent, most efficient, most stable way possible. I don’t think we’ll ever get rid of the people (or computers) in the middle making money off the customers, though. And there may even be something to be said for letting them do it the old way, out in the open, with cartels and fixed fees and Cadillacs to drive home to Long Island.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers