Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1440

April 11, 2014

What I Learned Watching 150 Hours of TED Talks

What makes for a great presentation — the kind that compels people’s attention and calls them to action? TED talks have certainly set a benchmark in recent years: HBR even asked Chris Anderson, the group’s founder, to offer lessons drawn from the three decades he’s run TED’s signature events in an article published last summer.

But experience and intuition are one thing; data and analysis are another. What could one learn by watching the most successful TED talks in recent years (150 hours’ worth), talking to many of the speakers, then running the findings by neuroscientists who study persuasion? I did just that, and here’s what I learned:

Use emotion. Bryan Stevenson’s TED talk, “We need to talk about an injustice”, received the longest standing ovation in the event’s history. A civil rights attorney who successfully argued and won the Supreme Court case Miller v. Alabama, which prohibits mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles convicted of murder, this is a man who knows how to persuade people.

I divided the content of his talk into Aristotle’s three areas of persuasion. Only 10 percent fell under “ethos” (establishing credibility for the speaker); 25 percent fell into the “logos” category (data, statistics) and a full 65 percent was categorized as “pathos” (emotion, storytelling). In his 18-minute talk, Stevenson told three stories to support his argument. The first was about his grandmother, and when I asked him why he started with it, his answer was simple: “Because everyone has a grandmother.” The story was his way of making an immediate connection with the audience.

Stories that trigger emotion are the ones that best inform, illuminate, inspire, and move people to action. Most everyday workplace conversations are heavy on data and light on stories, yet you need the latter to reinforce your argument. So start incorporating more anecdotes – from your own experience or those about other people, stories and brands (both successes and failures) – into your pitches and presentations.

Be novel. We all like to see and hear something new. One guideline that TED gives its speakers is to avoid “trotting out the usual shtick.” In other words, deliver information that is unique, surprising, or unexpected—novel.

In his 2009 TED presentation on the impact of malaria in African countries, Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist Bill Gates shocked his audience when he opened a jar of mosquitoes in the middle of his talk. “Malaria, of course, is transmitted by mosquitoes,” he said. “I brought some here so you can experience this. I’ll let these roam around the auditorium. There’s no reason why only poor people should have the experience.” He reassured his audience that the mosquitoes were not infected – but not until the stunt had grabbed their attention and drawn them into the conversation.

As neuroscientist Dr. A.K. Pradeep confirms, our brains can’t ignore novelty. “They are trained to look for something brilliant and new, something that stands out.” Pradeep should know. He’s a pioneer in the area of neuromarketing, studying advertisements, packaging, and design for major brands launching new products.

In the workplace your listener (boss, colleague, sales prospect) is asking him or herself one question: “Is this person teaching me something I don’t know?” So introduce material that’s unexpected, surprising or offers a new and novel solution to an old problem.

Emphasize the visual. Robert Ballard’s 2008 TED talk on his discovery of the Titanic, two and a half miles beneath the surface of the Atlantic, contained 57 slides with no words. He showed pictures, images, and animation of life beneath the sea, without one word of text, and the audience loved it. Why did you deliver an entire presentation in pictures? “Because I’m storytelling; not lecturing,” Ballard told me.

Research shows that most of us learn better when information is presented in pictures and text instead of text alone. When ideas are delivered verbally—without pictures—the listener retains about 10% of the content. Add a picture and retention soars to 65%.

For your next PowerPoint presentation, abandon the text blocks and bullet points in favor of more visually intriguing design elements. Show pictures, animations, and images that reinforce your theme. Help people remember your message.

How Founder Control Holds Back Start-ups

After enterprise tech start-up Box filed to go public last month, revealing founder Aaron Levie’s remaining stake to be just over 4% (plus stock options), commentators seemed compelled to note just how much control the 28-year-old founder had given up on the road to an IPO. One Quora user asked Levie how it felt to watch his investors “laugh to the bank after 10 years of blood, sweat, and tears.” TechCrunch was a bit more sympathetic, writing that “Levie didn’t have much choice. Box needed that funding.”

But that’s not quite right either, as a new working paper from Harvard Business School makes clear. While the culture in Silicon Valley often prioritizes founder control, new evidence suggests that such control often is a limiting factor on start-ups’ success. In Box’s case, Levie did have a choice, and by opting to dilute his own ownership, he was choosing to prioritize his company’s success. The paper in question is by HBS professor Noam Wasserman, whose previous work has examined the tradeoff entrepreneurs face between getting rich and being “king.” Wasserman’s earlier research chronicled the way this tradeoff shapes the decisions entrepreneurs make, like whether to have a co-founder or to raise venture capital. The new paper directly links founders’ control to start-ups’ value. He writes:

Startups in which the founder is still in control of the board of directors and/or the CEO position are significantly less valuable than those in which the founder has given up a degree of control. More specifically, on average, each additional degree of founder control reduces the value of the startup by 23.0%‐58.1%.

The data comes from a survey of 6,130 U.S. startups in the tech and life sciences industries, and the results hold even after controlling for factors like firm age, capital intensity, and economic conditions. Though some entrepreneurs might bristle at these findings, Wasserman posits a simple and compelling reason for the negative relationship between entrepreneurial control and start-up outcomes:

At the beginning of the founding journey, the vast majority of entrepreneurs are missing key resources, in the form of financial capital, human capital, and/or social capital. By attracting those resources to the company, founders have a better chance of growing a more valuable company. For instance, by attracting cofounders, hires, or investors, founders can access skills, contacts, and money they were lacking. However, as examined in this study, attracting those resources can come at a stiff cost: the imperiling of the founders’ control of the company they created.

A young start-up with little to no revenue needs some way to convince employees to join it. That is accomplished by offering a mix of salary and equity. The latter requires the founder to directly give up some ownership, and therefore control. The former, at least for founders who aren’t wealthy, usually means selling a stake in the company to venture capitalists in exchange for funding that can be used to pay salaries. Either way, the founder ends up owning less of the company, and therefore able to exert less control. And Wasserman’s data suggests that this tradeoff persists as start-ups aim to scale quickly, as the need for resources outpaces revenue.

It’s not that entrepreneurs like Levie give up control because they have no other option. More accurately, they face a choice between retaining control but building a less valuable company, and giving up control in order to build a more valuable one. Levie seems to have chosen the latter. The paper found this tradeoff to be remarkably consistent across sectors and circumstances, with VC involvement associated with a significant increase in start-up value. (The same was not true of angel capital, which is negatively associated with start-up value.) This isn’t necessarily because VCs are better at guiding a company, but rather because the funding they provide can be used to hire more employees and build and market new products. None of this is to say that prioritizing building a larger company is preferable to staying smaller and maintaining ownership. Wasserman’s research merely indicates that for many founders, there is a tradeoff between building a valuable company and calling all the shots.

The Behaviors that Define A-Players

Individual contributors sometimes ask themselves, “What will it take for others to recognize my potential?” They may simply want acknowledgement of the importance of the work they do. Or they may aspire to move into management. In some cases, they’ve been told that they’re doing fine and have been advised, “Just keep doing what you are doing.” Yet they see others being promoted ahead of them.

To see what separates the competent from the exceptional individual performers, we collected 50,286 360-degree evaluations conducted over the last five years on 4,158 individual contributors. We compared the “good” performers (those rated at the 40th to the 70th percentile) to the “best” performers (those rated at the 90th percentile and above). The first thing that struck us was the dramatic difference in productivity, as the graph below makes vividly clear.

Which leadership skills distinguished the best from the merely good? Here they are, ranked in order of which made the most difference. Exceptional individual contributors:

Set stretch goals and adopt high standards for themselves. This was the single most powerful differentiator. The best individual contributors set — and met — stretch goals that went beyond what others thought were possible. They also encouraged others to achieve exceptional results. And yet when we asked raters to select the four skills they thought were most important for an individual contributor to have, less than one in 10 chose high goals. It appears that setting stretch goals, since it’s not necessarily expected, is a behavior that separates top performers from average.

The less effective individual contributors are excellent “sandbaggers,” having concluded that the biggest consequence of producing great work and doing it quickly is more work. They fear their managers will keep piling on tasks until they reach a point where they can’t accomplish all that’s assigned. That’s a problem for them, surely — but also for organizations that don’t want to penalize valuable people for making extra effort.

Work collaboratively. When we asked people in the survey to tell us what they thought were the most important attributes for any individual contributor, they responded first with “the ability to solve problems” and second with “the possession of technical or professional expertise.” So it’s probably not surprising that these fundamental characteristics were shared by average and exceptional contributors alike. Third on the list, though, was “the ability to work collaboratively and foster teamwork.” And this trait did distinguish the great from the merely competent.

Many individual contributors strive to work independently. Some believe that if they remain solo performers, their contributions will be more likely to be noticed. They may be thinking of some educational experience where they stood out because their effort was acknowledged with high grades and test scores. If so, they fail to see that the main purpose of an organization is to create more value by working together than everyone can produce by working outside the company on their own.

Volunteer to represent the group. The best individual contributors were highly effective at representing their groups to other departments or units within the organization. If you want to stand out, have the courage to raise your hand and offer to take on the extra work of representing your group. In this way you will gain recognition, networking opportunities, and valuable learning experiences.

Embrace change, rather than resisting It. One of our clients describes her organization as having a “frozen middle” filled with people who resist and fear change. Change is difficult for everyone, but is necessary for organizational survival. The best individual contributors are quick to embrace change in both tactics and strategy.

Take initiative. Often individual contributors, by the very nature of their role in the organization, slip into a pattern of waiting to be told what to do. Great contributors develop a habit of volunteering their unique perspective and providing a helping hand. Think for a moment about the projects or programs going on in your own company. Which of them have your fingerprints all over them? Initiative requires more than doing your current job well.

Walk the talk. It’s easy for some people to casually agree to do something and then let it slip their minds. Most people would say that this is mere forgetfulness. We disagree. We believe it is dishonest behavior. If you commit to doing something, barring some event truly beyond your control, you should follow through. The best individual contributors are careful not to say one thing and do another. They are excellent role models for others. This is the competency for which the collective group of 4,158 individuals we studied received highest scores. That means, essentially, that following through on commitments is table stakes. But exceptional individual contributors go far beyond the others in their scrupulous practice of always doing what they say they will do.

Use good judgment. When in doubt about a technical issue or the practicality of a proposed decision, the very best individual contributors research it carefully rather than relying on their expertise to just wing it. Making decisions takes up a relatively small portion of the day for this group, but the consequences of the decisions they do make can be enormous. Outstanding contributors are open to a wide range of solutions and careful to consider what, and who, will be affected if something goes wrong.

Display personal resilience. No one is always right. Everyone suffers disappointments, failures, and disruptions. If they make a mistake, the best individual contributors acknowledge it quickly and move on. They don’t brood on other people’s mistakes. They ignore slights and hurtful comments. They realize that what undermines your reputation is not making mistakes but failing to own up to and learn from them.

Give honest feedback. We tend to think of feedback as a manager’s responsibility. And it is. Since this is not a formal role or usual expectation of individual contributors, it’s one of the behaviors that can make them stand out. Even done imperfectly, feedback from peers can be valuable because it’s so rare. If done with kind intent, demonstrations of how you might approach some task, gently raising questions a coworker may not have considered, or perhaps pointing out some specific things a colleague did that was particularly helpful to you or somewhat distracting, can be highly prized. The best individual contributors were able to provide feedback in a way that was perceived not as criticism but as a gesture of good will.

If you want to stand out from the pack, excelling at any of these nine behaviors can make a substantial impact on the way others perceive you. So we recommend selecting the one or two that might matter most to your effectiveness in your current assignment to work on improving. In making your selection, consider asking your manager and peers for feedback on how effective you are in all of these areas. Not only will they give you additional insight, but sharing your plans to improve will increase the likelihood that you will follow through. What’s more, if managers know of your improvement goals they may find development assignments that will help.

If you are a manager with individual contributors reporting to you, consider periodic coaching to encourage them to adopt more of the behaviors that will help them stand out from the crowd. It will strengthen their careers and will also help them to benefit your organization even more than they already do.

Has the Perma-Temp Job Market Arrived?

Many labor experts see the surge in temp jobs and contract work in the United States as a sign of a long-term shift in the employment market away from permanent jobs, according to the Wall Street Journal. In March 2014, more than 2.8 million workers, or 2.5% of the workforce, held temporary jobs, up from 1.7 million in 2009; nearly 40% of such positions are in manufacturing. Temp jobs allow employers to quickly staff up or downsize in periods of growth or contraction, and they tend to be lower-wage: The average weekly temp-job pay of $554 is one-third lower than that of all jobs.

Why Consumer Tech Is So Irritatingly Incremental

In the late 1960s, Michelin introduced the radial tire into the U.S. market. This was no surprise to the top five U.S.-based bias-ply tire manufacturers (Goodyear, Firestone, Uniroyal, B.F. Goodrich, and General Tire). After all, it was hardly a new technology; the first radial tire patents had been filed more than 40 years before. And they’d all seen radial tires take over the European market.

But even though radial tires were far superior to bias tires in terms of durability, cost per mile, and safety – and could be sold for an attractively higher price — they presented a challenge to U.S. incumbents. The process used to manufacture them was completely different from the one they used to make bias-ply tires. To produce radials, the U.S. giants basically needed to start their companies all over again — practically nothing of what they knew about producing bias-ply tires could be reused. Almost none of their patents would be useful (the tire business was the second most research-intensive industry in the U.S after chemicals). And so, even with the price premium, Michelin was the only company that had figured out how to produce radial tires profitably at scale.

Long story short, Michelin took over 50% of the entire tire U.S. market in the first 18 months after their introduction. And the Akron Ohio-based bias-ply tire manufacturing industry, which by 1920 had produced more millionaires than Silicon Valley has produced until just recently, essentially vanished. This is the transformational and dramatic effect of a superior technology entering an industry.

Again and again this story repeated itself in the 19th and 20th centuries. Gas lamps gave way to incandescent lamps. Refrigerators replaced ice boxes. Propeller planes yielded to jet engines. Joseph Schumpeter documented this pattern in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, coining the term entrepreneur, which he described as the person who, when successful, revolutionizes an industry through the process of “creative destruction” (creative for the superior technologies, destructive for all the established firms that would go out of business).

Tesla, Nespresso, and Geox are current successful examples of such high-end disruptions. But how common is this phenomenon today? How often have you seen a firm revolutionize an industry by creating a superior product using a new business model? Not nearly so often.

Superior technologies do not take over industries as frequently as they once did because consumers today are different from those of a few decades ago. In much of the 20th century, technological innovation produced products that had plenty of room for improvement, opening up opportunities for high-end disruption. This went on in most industries until about the 1980s. Before that, most cars, for instance, were notoriously unreliable, prone to rust, and unlikely to last past 100,000 miles. Television picture quality remained unsatisfactory as the technology evolved from vacuum tubes to solid state to digital to HD. As a result consumers learned to compensate. They learned to repair their cars or to recognize which brand of a particular product was currently best.

But as established firms’ efforts to improve their products (what we call “sustaining innovations” in disruptive innovation theory), together with some occasional high-end disruptions, made products and services cumulatively better year after year, so many became so good that consumers either could not appreciate the product improvements or were simply unwilling to pay for them. And so we find that even though tire manufacturers today can produce much better tires than radials, consumers find that radials work just fine and aren’t willing to pay more for these superior technologies. As a result most of these designs end up being discontinued; a good example is the Michelin PAX tire.

When an industry reaches this point, opportunities at the high end dwindle, and there’s far more scope for low-end disruptions – offerings that combine a technology with an new, incompatible business model to produce an offering that’s not better than the incumbent’s offer (since they don’t really need to be) but are instead radically simpler, far more convenient, or very much more affordable (the classical definition of disruptive innovation introduced by Clayton Christensen). Crest Whitestrips, for example, are radically more affordable and convenient than going to the dentist to whiten your teeth. Digital photography is far more convenient than developing film.

So many industries have in fact reached this point that, as things stand in the 21st century, we know very little about when a high-end disruption will succeed. Recent research suggests that they would work in industries where the following criteria are met:

The majority of consumers are highly dissatisfied with the current products or services. This occurs today most commonly in highly regulated industries that are hampered in some way from improving their offerings (as was the case, for example, when AT&T held a monopoly over telephony in the U.S.)

The industry is fragmented, which means that even the leading firms are limited in their ability to retaliate against upstarts.

The new company is fully integrated from the beginning, which means that it does not outsource critical functional departments to keep its cost structure low. Rather, it has developed an entirely new business model to profitably exploit a new, superior technology.

The new entrant uses a different distribution channel from the incumbents. This is perhaps the most important criterion, since it’s relatively easy for incumbents to use their market power to bar start-ups from established distribution systems.

The odds of meeting all of these criteria is relatively small. And so the odds of success of a new high-end disruption are correspondingly small. In fact, the rarity of a successful high-end disruption is the reason so many new and superior technologies that could do so much to help industries evolve and benefit customers never gain a market foothold.

Most entrepreneurs still think that just because their technology is superior it will inevitably be widely adopted in the marketplace. But consumers don’t work like that. Next time you come across an engineer aiming to commercialize a superior new technology, ask if his industry meets the criteria described above. If not, he’d do much better to focus on low-end disruption by encapsulating the technology in a product that is in some way simpler, more convenient – and seriously more affordable— than anything currently on the market. After all, technologies don’t dictate how they must be commercialized, managers do.

April 10, 2014

How Companies Can Embrace Speed

Generation to Generation: How to Save the Family Business

Most family-owned businesses—approximately 70%—last just one generation. Because an estimated 80% of businesses across the globe are family-owned, the low survival rate has alarming consequences. Consider this: In the United States alone, family-owned businesses (FOBs) are responsible for 60% of total US employment and generate 78% of all new jobs. Further, some of the world’s biggest companies are family-owned—News Corp, Samsung, Tata Group, and Walmart to name but a few—and more than a third of Fortune 500 companies are family-owned.

Our research on boards of directors and corporate governance has shed new light on many board practices and reveals the need for improvement in several areas including skills and selection, succession planning, and diversity. Given the vast impact of FOBs on every economy in the world, we were keen to learn if there were differences between the boards and governance practices of family and non-family owned companies.

In 2012, we (in partnership with WomenCorporateDirectors and Heidrick & Struggles) surveyed more than 1,000 corporate directors across the globe and broke out the FOB boards from the non-FOB boards. The results were striking: There was not one meaningful measure—from missing skill sets to the effectiveness of succession practices to creating more diverse boards and workplaces—on which FOB boards outperformed non-FOB boards.

Director Profiles. To begin, we compared the profiles of directors on the boards of family-owned vs. non-family-owned businesses and found few differences. A similar percentage held advanced degrees: 75% of FOB directors and 77% of non-FOB directors. When we looked at board service, we found that FOB and non-FOB directors had served on an almost identical number of boards in their careers (5.8 and 6.0, respectively) and were currently serving on the same number of boards (3.1).

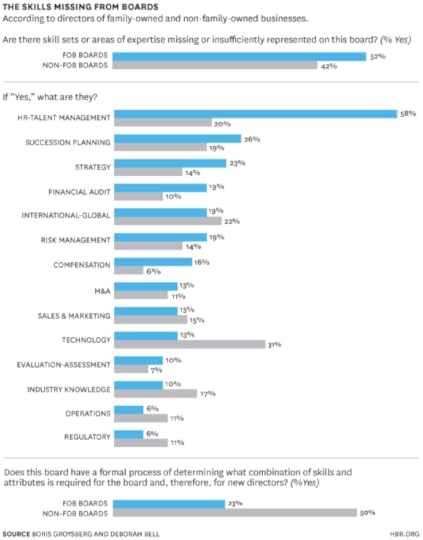

Skills and Assessment. Boards cannot govern effectively if they’re missing key skill sets. A greater percentage of FOB than non-FOB directors said skills were missing on their boards and the missing skill they named most was HR-Talent Management—to a degree almost 3 times that of non-FOB directors. There were other noteworthy differences: FOB directors said their boards lacked Succession Planning, Strategy, Financial-Audit, and Compensation skills to a greater extent than did non-FOB directors. Furthermore, less than a quarter of FOB directors (vs. half of non-FOB directors) said their boards had a process in place to determine skills required for the board and, therefore, new directors. We also found that FOB boards measured their own performance through regular, annual assessments less frequently than did non-FOB boards (45% vs. 67%, respectively).

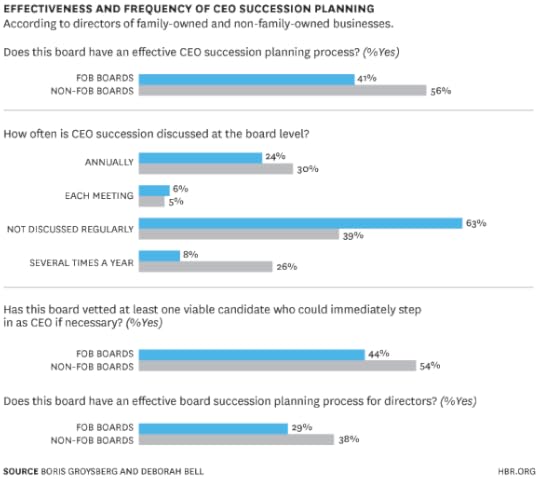

Succession. Just 41% of FOB directors said their boards had an effective CEO succession planning process (vs. 56% of non-FOB directors). Perhaps the most telling finding, however, was that 63% of FOB directors said CEO succession was not discussed regularly at the board level. In addition, only 29% of FOB directors said their boards had an effective board succession planning process in place for directors.

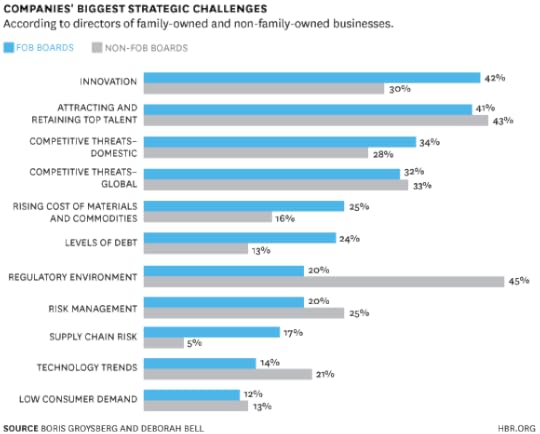

Strategic Challenges and Talent Management. We asked board members to tell us the biggest challenges their companies face achieving their strategic objectives and found directors from family-owned and non-family-owned businesses aligned on many challenges. For example, attracting and retaining top talent and global competitive threats were leading concerns for both.

But we also identified notable differences: namely a greater percentage of FOB than non-FOB directors viewed innovation as their top challenge, and FOB directors were also more concerned than their non-FOB counterparts about the rising cost of materials and commodities, levels of debt and supply chain risk. Conversely, a far greater percentage of non-FOB directors than FOB directors were concerned about the regulatory environment.

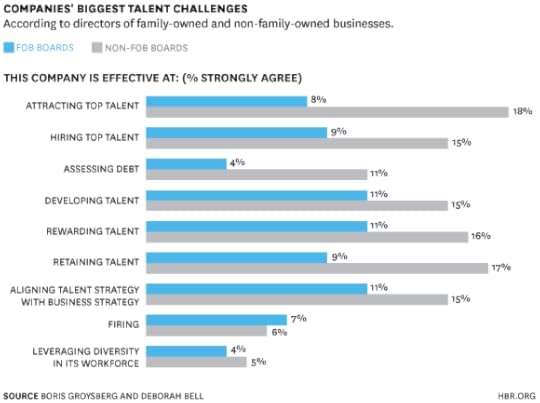

As we noted above, attracting and retaining top talent, was a foremost challenge for directors on both family-owned and non family-owned business boards. In our survey, we asked board members to rate their companies’ performance on nine dimensions of talent management: attracting top talent; hiring top talent; assessing talent; developing talent; rewarding talent; retaining talent; firing; aligning talent strategy with business strategy; and leveraging diversity in company’s workforce.

We found that directors from FOB boards rated their companies lower than directors on non-FOB boards on eight of the nine dimensions while both groups gave themselves an almost identical rating when it came to effective firing practices. The biggest differences were on the practices of attracting and retaining talent—with FOB boards rating themselves considerably lower than did non-FOB boards. What’s more, for the majority of practices FOB board ratings did not exceed single digits. If FOBs want to perpetuate their business through generations it is critical that they be able to attract and retain top talent.

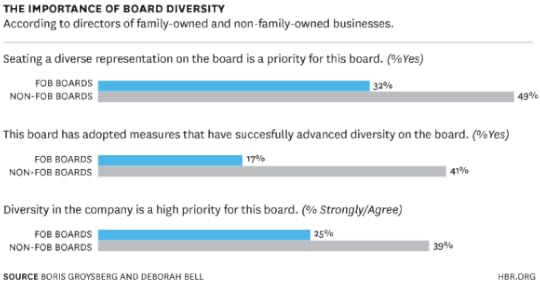

Diversity. We contend that in order to see greater progress in seating diverse boards, change must occur within three spheres: at the country, organizational and individual levels. Furthermore, although we have seen movement at the country and individual levels, much greater effort must be made at the organizational level, which we think may be the most determinative lever of change. Given that the majority of businesses in the world are family-owned, greater action on their part to create diverse boards and workplaces could have a substantial impact.

We found, alas, that FOB boards trailed behind non-FOB boards on diversity. Less than a third of FOB directors (vs. 49% of non-FOB directors) said that a diverse representation on their board was a priority. And when it came to actually implementing diversity, we discovered a stark difference: only 17% of directors on FOB boards said their board had adopted measures that successfully advanced diversity on the board (vs. 41% of non-FOB directors). Last, a smaller percentage of FOB directors than non-FOB directors said that diversity in the company was a high priority for their board.

How to Fix the Problems

Although our analyses found room for improvement on the boards of both family and non-family-owned businesses, we discovered that FOB boards lagged behind non-FOB boards—often substantially—on several important measures of board practice and governance. In fact, we tried to identify meaningful practices that FOB boards did better but could not find even one.

The lesser performance on family-owned business boards does not seem to be related to major differences in talent on FOB and non-FOB boards. Though our measures are very limited, we found director profiles and experience on both to be very similar. If a talent differential is not a factor, the lag would seem to be due to a greater extent of poor or non-existent practices and processes on FOB boards.

The good news is this can be fixed. It starts with the boards themselves. First and foremost, we recommend that FOB boards establish effective succession planning processes for both CEO and directors that include regular discussions of succession at board meetings. Not doing so could significantly limit the prospects of the business surviving into subsequent generations.

Second, FOB boards must institute a productive and regular assessment process of board and director performance. Regular assessment will help boards identify areas in need of development or change and also should help to identify skills needed on the boards—and when assessments are done at regular time intervals boards add a valuable contextual dynamism to the process.

Third, FOB boards should exert greater effort to make not only their boards but also their companies more diverse–especially in light of their concerns about innovation and performance on talent management. Improving their talent management practices with an eye toward adding talent with a diverse mix of backgrounds, skills, experience, and knowledge may help to address gaps in skills and spur innovation.

Overall, family-owned business boards need to become better at governing by implementing best practices and processes because good governance may lead to higher survival rates and smoother generational transitions.

Methodology

We surveyed more than 1,000 board members in 59 countries. For the family-owned business breakout: FOBs made up 8% of the sample and non-FOBs constituted 92% of sample. The following multiple choice list of 14 skills was used for skill sets missing from the board question in the survey: Compensation; Evaluation-Assessment; Financial-audit; HR-Talent management; Industry knowledge; International-Global; M&A; Operations; Regulatory, legal and compliance knowledge; Risk management; Sales & Marketing; Strategy; Succession Planning; and Technology. Participants could choose as many as applied (plus there was a write-in option of “other”).

Why Your Employees Should Be Playing With Lego Robots

Two years ago, Swedish communications technology giant Ericsson found itself looking for a way to explain the value it saw in the Internet of Things. Rather than publish another whitepaper on the topic, the company struck on a different communication tool: Legos. More specifically, Lego robots.

Ericsson used Lego Mindstorm robots in a demonstration at the 2012 Mobile World Congress to bring to life its vision of how connected machines might change the way we live. A laundry-robot sorted socks by color and placed them in different baskets while it chatted with the washing machine. A gardening-robot watered the plants when the plants said they were thirsty. A cleaner-robot collapsed and trashed empty cardboard coffee cups that it collected from the table, and a dog-like robot fetched the newspaper when the alarm clock rang.

Rather than merely talking or writing about its vision, Ericsson saw robots as a perfect medium for explaining its ideas. This is more than just a smart marketing campaign. As a variety of researchers have argued, it may offer a way to better equip workers with the skills they need to succeed in the 21st century. Training programs that encourage the use of robots to achieve goals – not just by playing with them, but by building them — encourage participants to use their creativity and natural curiosity to overcome problems through hands-on experiences.

Lego’s Mindstorm robots (or education and innovation kits as they are sometimes known) were developed in collaboration with MIT Media Lab as a solution for education and training in the mid to late 90’s. The work was an outcome of research by Professor Seymour Papert, who was co-founder of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab with Marvin Minsky. Papert later co-founded the Epistemology and Learning Group within the MIT Media Lab. Papert’s work has had a major impact on how people develop knowledge, and is especially relevant for building twenty-first century skills.

Papert and his collaborators’ research indicates that training programs using robotics influences participants’ ability to learn numerous essential skills, especially creativity, critical thinking, and learning to learn or “metacognition”. They also emphasize important approaches to modern work, like collaboration and communication.

This form of learning is called constructionism, and it is premised on the idea that people learn by actively constructing new knowledge, not by having information “poured” into their heads. Moreover, constructionism asserts that people learn with particular effectiveness when they are engaged in “constructing” personally meaningful artifacts. People don’t get ideas; they make them.

Papert’s influential book Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas as well as extensive scientific research into fields such as cognition, psychology, evolutionary psychology, and epistemology illustrate how this pedagogy can be combined with robotics to yield a powerful, hands-on method of training.

In training courses that use robotics, the program leader sets problems to be solved. Teams are presented with a box of pieces and simple programs that can run on iPads, iPhones, or Android tablets and phones. They are given basic training in the simple programming skills required and then set free to solve the problem presented.

Problems can be as ‘simple’ as building a robot to pass through a maze in a certain time frame, which requires trial and error and lots of critical thinking. What size wheels to use for speed and maneuverability, what drain on battery power, which sensors to use for guidance around walls. One team may decide to build a small drone to view and map out the terrain of the maze, this would require theorizing on the weight of the robotic drone and relaying data filmed to a mapping system which the on-ground robot could use to negotiate through the maze.

It is an entirely goal-driven process.

Participants get to design, program, and fully control functional robotic models. They use software to plan, test, and modify sequences of instructions for a variety of robotic behaviors. And they learn to collect and analyze data from sensors, using data logging functionalities embedded in the software. They gain the confidence to author algorithms, which taps critical thinking skills, and to creatively configure the robot to pursue goals.

Participants from all backgrounds gain key team building skills through collaborating closely at every stage of ideation, innovation, deployment, evaluation and scaling. At the end of the training teams are required to present their ideas and results, building effective communication skills.

It is quite astonishing to see how teams have developed robots to achieve tasks such as solving Rubik’s cubes in seconds, playing Sudoku and drawing portraits, creating braille printers, taking part in soccer and basketball games. These robots have even been used for improving ATM security.

Using robots in training programs to overcome challenges pushes participants out of their comfort zone. It deepens their awareness of complexity and builds ownership and responsibility.

The array of skills and work techniques that this kind of training offers is more in need today than ever, as technology is rapidly changing the skills demanded in the workplace.

Instead of programming people to act like robots, why not teach them to become programmers, creative thinkers, architects, and engineers? For companies seeking to develop these skills in their employees, hands-on goal-focused training using robots can help.

How China’s Growth Imposes Costs on the Rest of the World

It has long been assumed that China’s economic growth creates upward pressure on the price of oil, but to what extent? A team led by John Beirne of the European Central Bank estimates that the impact was about 1% of the global oil price in 2011 and will rise to 3% to 4% by 2030. If China’s economy continues to expand at 8% or more, by 2030 its growth will cost the world more than $180 billion in higher oil prices, the researchers say.

The Power of Your Vote Should Not Reflect the Size of Your Wallet

In September 2004, I attended a reunion of my class at Harvard Business School, four years after the Supreme Court decision putting George W. Bush in office and immediately before the next Presidential election. We invited Elaine Kamarck, then at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, to discuss elections in a country in which the electorate was so evenly divided. She explained how the too-close-to-call campaigns spurred the funding arms race to new heights.

During the Q&A, a member of the audience offered the thought that many voters had little grasp of or interest in the issues debated in the campaign, and asked why everyone had the right to vote. Shocked silence. “How,” she asked, “would you propose to decide who should have a vote?” He responded with one word: “Money.”

From his lips to John Roberts’s ears, apparently. This week’s McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission decision, removing a limit on the amount individuals could contribute to political campaigns, came down to this, in a New York Times recap:

Leveling the playing field is not an acceptable interest for the government, Chief Justice Roberts said. Nor is “the possibility than an individual who spends large sums may garner ‘influence over or access to elected officials or political parties,’” he added, quoting Citizens United.

Justice Breyer, writing for the four-Justice minority, disagreed. “Where enough money calls the tune,” he wrote, “the general public will not be heard.”

And even as cases like Citizens United and McCutcheon make it easier for the wealthy to influence the government, it’s getting harder for people with less money to vote—for example, Ohio and Wisconsin have recently reduced weekend voting hours “favored by low-income voters and blacks, who sometimes caravan from churches to polls on the Sunday before election.” Voter ID laws have been passed in 34 states; these laws are more likely to make it difficult for the poor to vote. A spate of other restrictive laws were passed in the months immediately following another Supreme Court decision, Shelby County v. Holder, in which a major section of the Voting Rights Act were overturned.

A lot of attention has recently been paid to the data on the concentration of income. It’s harder to measure influence inequality than income inequality—the power of the “1%” is not as easy to quantify as their dominant financial assets. But the same dynamics of concentration are at work—and they reinforce one another. Consequently issues of public good are not decided in favor of the public, as Breyer suggests. (For example, who would net neutrality benefit? Only the public—now facing a diminished power to make their votes count.)

As the case of Egypt—as well as Ukraine and Russia—have recently demonstrated, elections alone are no guarantee that democracy will flourish. Lawrence Lessig, in his book Republic, Lost, describes the change in the attitudes of Congress have shifted in the past thirty years. He cites John Stennis in 1982, balking at appearing at a fund-raiser at which defense contractors would be present (Stennis was then Chairman of the Armed Services Committee.) Stennis asked, “Would that be proper? I hold life and death over those companies. I don’t think it would be proper for me to take money from them. “ He goes on to quote then-Senator, now Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel: “There’s no shame anymore. We’ve blown past the ethical standards, we now play on the edge of the legal standards.” The McCutcheon decision redraws that edge.

The United States is hardly the only democracy to suffer from corrupt interactions of money and power. Several years ago, I was flying from Mumbai to Boston shortly after the Indian elections in which the BJP Party was voted out of power for the first time in decades. The Times of India reported that the new administration would have to adjust the responsibilities of the Ministries so that its coalition partners could hold offices with the opportunities for patronage and graft commensurate with their contributions to the victory (reportedly the telecoms responsibility was particularly rich in this regard.) This was written about—including the word “graft”—as how politics was to be conducted in the ordinary course of business, not as any sort of inappropriate behavior.

Landing briefly at Heathrow, I picked up the Times of London, and read about Members of Parliament writing off their mothers’ country cottages as part of their expenses, charged to the taxpayer. This, however, did excite a high degree of outrage, if little surprise. Finally, arriving home to the Times of New York, I read that executives of energy companies had been invited to Vice President Cheney’s office to discuss their views on energy policy. Each of these democracies seems to have it’s own way of dealing with issues of corruption—but the McCutcheon case is one more step towards legalizing it.

Back at my reunion, Professor Kamarck paused a beat, and then went on with the Q&A. No one rose to point out the danger represented by thinking of electoral power for sale. I assumed that signaled that others in the room saw what she saw—a suggestion so outside the bounds of democratic practice that it wasn’t worth addressing. Now I’m not so sure they weren’t just nodding in silent agreement. But at least, ten years later, in response to McCutcheon, campaign reform groups held rallies in 150 towns in 41 states and in front of the Supreme Court, according to Money Out/Voters In. And Lessig is walking 185 miles across New Hampshire to build a coalition to fight the influence of money in politics.

They are doing the Founders’ work. When Ben Franklin’s was asked, at the end of the 1787 Constitutional convention, “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” Franklin responded, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers