Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1438

April 16, 2014

Bonuses Should Be Tied to Customer Value, Not Sales Targets

Why would you eliminate sales targets as a way to evaluate, motivate, and reward your sales staff?

That is perhaps the most frequent question I’ve received since 2011 when GlaxoSmithKline changed the link between the bonus pay of our pharmaceutical sales professionals in the United States and the numbers of prescription sold for a particular medicine. It is after all a well-established incentive plan used across a spectrum of industries.

But at GSK and across the pharmaceutical industry, we have a very special responsibility to patients and caregivers. They depend on us to do more, feel better, and live longer. It is that responsibility and the crucial importance of trust in our relationships that means we are judged to a higher standard than many other industries.

I have seen the good that our industry does in transforming the lives of patients living with diseases such as cancer, HIV, asthma and diabetes. But I have also heard doctor complaints that our incentive systems are not focused on the interest of the patient.

We are, of course, concerned that some see perceived conflicts of interests in the way we run our business, particularly related to incentive plans for our sales professionals and the financial links we have with health care practitioners.

So, we realized that “how” we do our job is just as important as what we do. Ultimately every leader knows that you get the behavior you reward. At GSK, we’ve decided that bonus incentives for our sales professionals should be tied to the value we bring in ensuring that patients are appropriately treated with our medicines.

This patient focus is a core value for us, along with transparency, respect, and integrity. So instead of specific prescriptions sold, we began to reward our representatives for their patient focus, understanding of their customer, problem solving, and level of scientific knowledge as measured by tests and other assessments. That approach may not seem like radical thinking, but when we changed our focus away from numbers of prescriptions sold to patients well served, it set us on a different path that, thus far, we walk alone.

Critics may say it took a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice over past sales and marketing practices to reach that conclusion. But we dropped sales targets well before the settlement, recognizing that traditional sales incentives were out of line with society’s expectations for our industry, and we had to change. Ultimately, past practices affected customer trust and satisfaction and, as a result, damaged the reputation of our industry.

As a global business with shareholders and major investments in research, sales are important to us. I watch the sales numbers and I’m concerned if they dip. But our value metrics are important to our long-term growth, and we hope they will help restore trust in our company and our industry.

Our employees quickly recognized that this change aligned with our values. But implementing a new approach without a pattern or road map to follow admittedly was painful at times. We had to identify new metrics to evaluate aspects of employee performance such as problem solving, business acumen, and demonstration of our values. It is one reason we are encouraged by the positive response of health care professionals. I accompany representatives to visit doctors and have heard their reactions firsthand. Some doctors have even reopened their doors to GSK representatives. We believe this new way of working has become a core strength for us.

That’s why we are now working to extend that practice to thousands of sales representatives in 140 countries around the world and are taking the additional step of halting payments to physicians for speaking to their peers on behalf of our medicines. That’s no small commitment, but my experience in the United States over the past two years has strengthened my belief that this is the right path for our company as well as the patients we serve, wherever they live in the world.

Renewing focus on our values by reshaping employee incentives is helping us do more to help doctors help their patients. We are not the only industry that needs to better meet society’s expectations. Every one of us in the corporate world must look at our business through the eyes of our customers and nimbly respond to their changing expectations.

Clumsy Feedback Is a Poorly Wrapped Gift

People on your team offer you gifts – not just at special occasions, but all year. These gifts aren’t tangible, and they’re not wrapped up in lovely boxes with beautiful bows. These gifts are nicely wrapped in a compliment, or, more often, not-so-nicely wrapped in a criticism or complaint.

Effective leaders open these gifts, regardless of the wrapping, to learn what they are doing that’s negatively affecting others on their team. For example, when your boss says, “You did a great job on that presentation,” the compliment is the wrapping. You can go past the wrapping and open the gift to learn more by saying something like, “Thanks. I’m curious, what did I do that was great? I want to make sure to keep doing it.”

Many of us judge a gift by its wrapping, so when it’s poorly wrapped – when it looks bad, sounds bad, or feels bad, we don’t open it. If, in a performance appraisal meeting your direct report says, “My division would have hit all our numbers this year if I had more support from senior leadership,” you may ignore the comment or respond with a dismissive remark. But when you respond this way, you turn down some of the most valuable learning opportunities you can receive.

Why do we reject these potentially valuable gifts?

They are vaguely worded. Research shows that leaders consider negative feedback more useful if it is specific. But gifts are often purposely vague, so the givers feel that they are taking less risk. Because we equate vagueness with being less helpful, we are less likely to open the gift.

They come as a surprise. Gifts don’t often come with a heads-up such as, “I’d like to give you some feedback.” They just get tossed into the conversation without warning. When they seem off-topic or feel unexpected, we are less interested in exploring the gift and less prepared to respond.

They feel inconsiderate or threatening. The same research shows that leaders are also less likely to consider feedback if it is given in an inconsiderate manner. A gift like, “My division would have hit all our numbers this year if I had more support from senior leadership” can seem ungrateful or sting. That leads us to respond defensively; either we ignore the gift or reject it by saying something like, “We’re here to talk about your performance, not mine.” We want our negative feedback delivered perfectly; if it’s not, we let our own defensiveness undermine our ability to learn and improve.

How do you open gifts rather than turn them down? Try these steps:

Notice when people say things that lead you to feel upset, surprised, or threatened. When you feel this way, there is a good chance that you’ve just been given a gift that’s poorly wrapped.

Focus on the potential, not the delivery. When you focus on how the gift was delivered, it’s easy to dismiss it as off-topic, ungrateful, or whiny. But rejecting a gift doesn’t make the underlying issue go away; it just prevents you from becoming aware of it and being able to address it. There is a Talmudic saying, “Who is wise? He who learns from everyone.” Suspend your judgment about the wrapping, and focus on your opportunity for learning.

Respond with curiosity. This leads you to open the gift by saying something like, “I thought I was fully supporting you, but it sounds like I wasn’t. What was I was doing – or not doing – that you thought wasn’t supportive?” When you respond with curiosity and compassion, you learn things that people were previously unwilling to discuss with you. Discussing these previously undiscussable issues enables you to solve problems that were previously unsolvable.

When you accept a person’s gift – no matter how poorly wrapped – by responding with curiosity and compassion, you are giving a gift in return. You are creating the trust needed to talk about things that really matter and that will lead to better results. This type of gift is priceless.

Ever Notice That UPS Trucks Rarely Make Left Turns?

An estimated 90% of the turns made by UPS delivery trucks are right turns, and that’s intentional, according to the Washington Post. Left turns are seen as inefficient, because they leave trucks sitting in traffic longer. The logistics company says a policy of minimizing left turns has helped it save more than 10 million gallons of fuel over the past decade. Left turns (in countries where people drive on the right) are dangerous, too: New York City officials say left turns are 3 times more likely than right turns to cause a deadly crash involving a pedestrian.

How GE and IBM are Playing Global Development to Win

Most big corporations follow global development trends. Where there is economic growth, there is opportunity, and the companies that can predict where growth will take place are better positioned to take advantage of it. That is the reactive approach to economic development.

In the last few years, a more powerful dynamic has gained traction. CEOs are proactively engaging with emerging market government to spur economic development and create opportunities for their companies. In the fast growth markets of Asia, Africa and Latin America, national governments are responding to a more empowered citizenship, and looking for corporate partners to achieve their development goals. Companies that fill that need effectively are doing more than reacting to development. They are playing development to win.

General Electric is a good example. Four years ago, GE initiated a strategy to compete more effectively in Africa, one of the fastest growing regions in the world in terms of GDP. GE did more than take advantage of growth as it came. The company’s leadership moved proactively to accelerate it and shape it. “If we see a country where reward outweighs the risk, we want to invest,” CEO Jeff Immelt says in Success in Africa. GE spent months understanding the development priorities of countries where it planned to invest. Partnering with those governments, the company sought out discussions at the ministerial and head-of-state level to identify and work on the country’s most significant infrastructure challenges. The results are encapsulated in a “Country-Company MOU,” which describe key challenges the country faces and the role GE will play in helping meet them. For example, the two parties identified the challenge of national electrification and committed to work together to bring $10 billion of investment and 10,000 megawatts of new power online, along with local manufacturing and training. Emerging market infrastructure is a segment many Western companies have ceded to China, but GE is winning contracts because it is playing development to win.

IBM is doing something similar in data analytics. CEO Ginni Rometty took the top job in 2012, and identified Africa as a locus of technological growth early in her tenure. IBM identified a set of “Grand Challenges” facing the continent that could be addressed through superior data analytics, including water and sanitation, energy management, financial services, transportation, public safety, healthcare, and agriculture. Last month, IBM launched a dialogue with the government of Nigeria. It was co-hosted by the Minister of Technology and included ministers from the cabinet charged with meeting the Grand Challenges IBM identified. Rometty, on her second trip to the region in three months, led the session for the company. IBM is speeding the region’s growth, and helping shape its direction. That is playing development to win.

I recently spent some time with Bob Diamond, the former CEO of Barclays. Now head of Atlas Mara, he’s positioning the investment company to play development to win. Earlier this year, they raised $325 million in the public markets and this month acquired BancABC, a bank with operations in Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. “Governments want banks who will lend to businesses and homeowners,” Bob explains, “That’s what we intend to do. The private sector is growing in Africa and we plan to enable that in multiple countries.”

Playing development to win does have costs. It requires an up-front investment of money and time to understand the growth challenges within each host country or region and to establish the government and civil society relationships needed to act on those challenges. It also demands senior management and board involvement. Companies playing development to win have CEOs traveling to the region 2-3 times per year, supported by engagement of the full management team. Furthermore, the returns on investment are long term. For a large company, it’s common to invest for a decade or more before shareholders see material earnings. The anticipated scale of new business has to be large enough to warrant that.

Playing development to win should not be mistaken for corporate social responsibility (CSR). Sustainability and core values support any great company, but expanding long-term earnings by meeting big development challenges takes more. At a company that’s playing development to win, business units are leading the effort, enabled by sales, marketing, finance, supply chain management, CSR, and social investment.

Some might see playing development to win as cynical or undermining the cause of inclusive growth. It’s neither. Cynicism would be to bet against development. The companies playing development to win need the institutions and policies with which they are engaging to yield tangible results. If the government of Nigeria fails to deliver widespread, low-cost power, the fallout for GE will be significant.

Playing development to win will be the hallmark of great companies operating in emerging markets. Over the next decade, they will be the companies addressing the most pressing challenges in countries where the potential for growth is ripe. As a result, they will shape the landscape in which they compete, attract and retain superior talent, build stronger brands and enjoy stronger relationships with customers in the fastest growing global markets.

April 15, 2014

Prototype Your Product, Protect Your Brand

Designers and entrepreneurs have been experimenting with live prototyping — putting unfinished product ideas in the context of real markets and real customer situations — for years, and now bigger businesses have begun to catch on. Many executives, eager to avoid over-investing in the wrong ideas, are intrigued by this approach, but they’re leery of putting unpolished products and services out in the market. Might we tarnish our brand? Will customers trust us less once they’ve experienced the rough edges of our prototype? Might we expose our strategy to competitors?

The concern can be valid, but by answering a few questions, and playing with a few variables, you can usually find a way to conduct market experiments that does not put your relationship with customers at risk.

A good first step is to get a sense of your customer’s sensitivity to change and to “rough edges” in your offer. We find the following approaches useful to help executives understand the degree of caution they need when running market experiments in public:

Assess your brand history: Does your company have a record of experimenting in public? If so, how have consumers responded? Do your core customers value your inventiveness or your reliability? If you’re H&M, your customers expect you to be “out there.” If you’re Levi’s they might be fiercely loyal to your classics, and wonder why you’re shaking things up.

Assess competitive benchmarks: Identify the quality “floor” of your offer. Is quality essential in your market, or simply a nice-to-have. For a car or legal services, this floor will be very high, but for an entertainment service, it might be low.

Assess analogous industries: Looking at direct competitors can sometimes be misleading. Look across adjacent industries. If you’re in automotive, you might look at other highly regulated industries, like healthcare and finance, which manage to experiment considerably despite stringent regulatory environments.

Prototype prototyping: Most simply, this means talk to you customers about prototyping. Instead of simply launching the prototype, bring your concepts or prototypes out and talk about them with customers. Get them to imagine what it would be like to come across these prototypes without knowing that they aren’t “real” products. Would they be excited about trying new things? You might have a group of customers who are willing to experience some rough edges of an unfinished product to feel part of building something new.

Armed with an understanding of your baseline customer expectations it’s time to plan your experiment. The most effective way to reduce your risk is typically to invest more to achieve an acceptable level of quality. But you have to be sure that increased spending will improve quality, and that you’re not simply wasting money. Consider investing more per customer, rather than investing in the operations that deliver quality. For example, in evaluating an automated digital legal service, you might have actual lawyers working behind the scene to deliver the service to test the market need first. You can invest in algorithms and automation later.

Another effective de-risking approach is to contain the experiment to specific moments of the customer experience. Focusing initially only on those moments that highlight the biggest business risks can decrease development requirements and customers’ interaction time with your prototype. For snack products, one of these key moments is when a customer chooses the product, so you might produce high-fidelity packaging so that the concept stands out against the shelf of competitors, but fill the packages with Legos (which sound and feel a lot like a crispy snack through the package). At this point, you’re testing the brand promise, not the customer’s willingness to pay or how the taste fulfills on the brand promise, so you don’t need to provide a full end-to-end experience.

You can also contain your experiment by calibrating exposure. Testing with large audiences might yield greater statistical significance, but nuance can get lost. Perhaps more importantly, testing new ideas with smaller audiences means that you can be bolder. Some companies like Facebook and AirBnB use limited release to allow any employee to release their product changes — large and small — to the public. These companies measure the impact of shipped features on customer behavior. Changes that have desirable outcomes are released to bigger audiences. This approach is easier for software companies, but manufacturing innovations like 3D printing have provided ways to launch physical products at limited scale.

If, after following these approaches, you feel that your market may still be hostile to the experiment or that the prototype still doesn’t deliver the value proposition to the customer, be transparent about that fact. Let participants know that they are engaging with a prototype that may not launch. One way of doing this is to create a sub-brand that is clearly about introducing new and unfinished ideas. For example, Google Labs is an arm of Google that focuses on creating revolutionary new products. They have been able to release Google Glass to the public before it’s ready for mass market use. We find that customers are generally enthusiastic about giving input if they know what they’re getting themselves into.

To protect against potential inconvenience to the customer, you could offer the option to switch back to the original service or product if they lose patience with the prototype. For example, if you’re developing software you might ask customers to opt in to product updates for the services that they would consider purchasing to get a sense of genuine product interest. This approach yields valuable information about product appeal, and you’ll gain access to a community to tap for feedback as your product evolves. Meanwhile, when customers opt-out, take it as an opportunity to understand why via a survey or even a live conversation.

While running prototypes can seem scary in the moment, the risks are much lower than launching a flawed product or service. Think about the above levers to reduce risk and avoid cutting corners in a way that is detrimental to your experiment. Markets move fast, and more of your competition will be experimenting to improve their market position. It’s better to test and build than be left with an outdated business.

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

In the 1989 movie Dead Poet’s Society, Robin Williams, playing the iconoclastic English teacher John Keating, dismisses the notion that you can judge the perfection of a poem mathematically by plotting how artfully it employs meter, rhyme, and metaphor against how important the subject is. Rather than have his students think they could graph the relative merits of, say, a Shakespeare sonnet against a poem by Alan Ginsberg, he has them rip up their textbooks. Data can’t tell us anything about stories, he’s saying, as pages of Understanding Poetry, by Dr. J. Evans Pritchard, Ph.D., fly all over the room.

Businesspeople are often advised to turn their data into stories to make them more persuasive. And that is certainly good advice. But they are given precious few tools to help them do that. It turns out though, John Keating notwithstanding, that graphs can be remarkably useful in demonstrating the mechanics underpinning an effective story. One person who’d given this a lot of thought was novelist Kurt Vonnegut, a real-life literary iconoclast if there ever was one.

Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism recently shed a spotlight on Vonnegut’s story graphs in its publication Nieman Storyboard (a wonderful resource on the art of storytelling in itself). Vonnegut devoted his master’s thesis at the University of Chicago to studying the shapes of stories. The thesis was rejected (apparently, Vonnegut’s advisors were of the John Keating school of literary criticism). But his ideas are thriving online in various storytelling tutorials. Nieman offers up Vonnegut’s original presentation, now on YouTube, in which he graphs some of the most basic story structures and explains how they work.

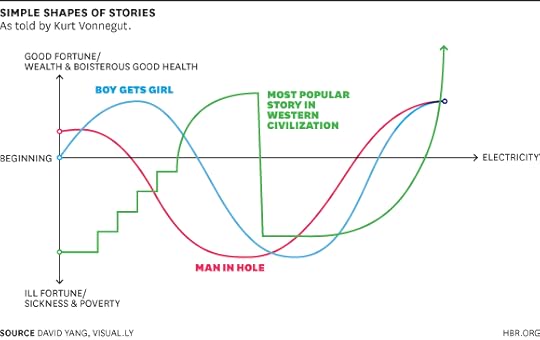

“There’s no reason why the simple shapes of stories can’t be fed into computers,” Vonnegut begins. First up is one he calls Man in a Hole. “It needn’t be a man, and he needn’t fall into a hole,” he adds, for the metaphorically challenged among us. “That’s just an easy way to remember it.”

In the tradition of J. Evans Pritchard, he starts by drawing the vertical Good Fortune/Ill Fortune (or G-I) axis, with “sickness and poverty” at the bottom and “wealth and boisterous good health” at the top. At the midpoint, he draws his x axis – B (for beginning) to E (for electricity). He’s joking of course, but he also wants to underscore the point that this is an exercise in relativity, since it’s the shape of the curve that matters, not the specific data points.

Then he places his chalk on the y axis a bit above the midpoint (“Why start with a depressing person?” he quips), draws a sine wave dropping down toward the bottom and rising up again: Somebody gets into trouble and gets out of it. “People love that story,” he says. “They never get sick of it!” (This is doubly obvious is when you draw the business parallel by substituting a term like business, strategy, revenue, IT, HR, or whatever for the word somebody).

He goes on to graph Boy Meets Girl, starting right at the midpoint of the y axis – “an average person on an average day, not expecting anything.” He draws a double sine wave rising up and then down and then up again. “Something wonderful happens, Oh hell. Got it back again” In business terms, the classic turnaround story (IBM comes to my mind here, and more than once).

The next one is more complicated, he warns. Despite what he’s just said, he starts at the bottom and stays there—a wretched person, a little girl, no less, has lost her mother and her father has married again to a horrible woman. The curve hovers at the bottom. A fairy godmother arrives, bestowing much-needed resources (shoes, a dress, mascara). With each gift, the line goes up incrementally, like a bar graph. The girl goes to a dance. The clock strikes 12:00. The resources dry up. The line drops almost straight down, but not all the way back (she has those memories, and maybe some IP or a valuable customer base). The prince finds her, the shoe fits. Facebook buys your start-up, the curve shoots up as you achieve off-scale happiness.

It so happens, he says, that this Cinderella story is “the most popular story in our Western civilization. Every time it’s retold somebody makes another million dollars. You’re welcome to do it.” Well, sure…

Here are all three stories, conveniently plotted on a single graph:

But watch the video (it’s less than five minutes long), and two things become apparent. The first is certainly that so many successful business stories follow patterns embedded in Western civilization’s most primal literary conventions. It’s easy to see why marshalling data to tell one of these kinds of stories – rags turning into riches, mistakes rectified, challenges overcome, the right resources and the right contacts saving the day — would be so compelling. And there’s probably an argument here for reading more fiction, to give John Keating his due.

The second is that Vonnegut’s delivery matters as much as his ideas. His timing is perfect. His language is concrete and unexpected. He’s showing you the simplicity that underlies apparent complexity – that’s what data are so good at doing. But he’s just as concerned with making sure you’re paying attention — since no one is persuaded by something they don’t remember.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious

How to Tell a Story with Data

To Go from Big Data to Big Insight, Start with a Visual

How GE Uses Data Visualization to Tell Complex Stories

How to Override Your Default Reactions in Tough Moments

“It’s 9:00am, you’re across the table from a colleague who doesn’t like you or the changes you’re proposing, she’s pushing all your hot-buttons and resisting your efforts to get her to support the change. What’s your typical reaction?” I recently posed this question to a group of executives.

About two thirds of the executives admitted that their typical behavior is competitive: return the aggression and argue to win. The other third said they typically do the opposite: retreat, recoup, and try again later. But either way, it was a default reflex – not a strategic response.

We all have default behaviors. And when we are in the moment, trying our best to perform well, how we handle these automatic reflexes can be the difference between success and failure. It’s these moments that add up to the larger tasks and projects that are our work. Moments in which behavior – what we think, feel, say, and do – is the primary driver of performance.

I can remember a pivotal meeting after weeks of working with a team on a product idea. After presenting it to a colleague, I found myself fielding unexpected negative feedback. My default was to fight back, with facts. I’m an evidence-based manager, and this approach often works, and works well. But not this time. I hadn’t included this colleague in the process, and he was upset despite the facts. Unfortunately, my highly automated default behaviors were running the show. Had I paid more attention to his tone and body language, and been able to put a little mental distance between the “automatic-me” and the situation, I would more easily have seen what was happening. I had experienced a failure of attention and self-control.

Automatic behaviors do have their place – they save time and effort. When you continually face the same type of meeting, with the same people, with the same objective, what has worked for you in the past may work again now. So why not embrace these defaults? Wouldn’t our professional lives be easy if we could allow well-tuned default behaviors to take over at work, in the same way we can put our minds on auto-pilot while we drive there?

The problem with that approach is that the workplace is too dynamic. Situations rarely repeat. Human behavior is diverse, erratic, and often unpredictable.

As I experienced when arguing the facts with my upset colleague, and as I have seen over and over again with executives and management students, defaults are dangerous and too often lead to unproductive behaviors and outcomes.

We know this – and yet our defaults are devilishly hard to overcome.

Imagine you’re a judge, and you’re trying to decide whether a convicted felon should be given parole. What would be your default? One would hope that parole judges override their default behavior to think carefully before each ruling. In a study published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers found that a group of highly experienced parole judges did reason more carefully – particularly at the start of the day and after every food break, when on average they granted parole to 65% of the felons. However, as judicial sessions wore on, favorable parole judgments fell to an astonishing 0% prior to each food break.

Research like this shows just how much evading our defaults requires self-control, and how much our level of self-control varies throughout the day depending on a range of psychological and physiological factors like how well we slept, the time since our last meal, how hard we’ve already worked to control ourselves. And critically, like those parole judges, we are often not aware of these fluctuations in self-control as we wend our way through the workday. When self-control wanes, our ability to catch and override default behaviors also wanes. Our more planful selves can lose control, giving way to reflex behaviors triggered on the spot.

So what you can you do to avoid unconscious defaults and provide yourself more behavioral flexibility in the moments of truth that matter most? Here are three suggestions that I have seen work well:

Know your defaults: Make a list of the frequent “moments of truth” that populate your workday: the meetings, conversations, negotiations, conflicts, and other situations when your behavioral performance is of paramount importance. These are typically challenging interpersonal situations in which how you react, what you say, and what you do can be commandeered by defaults. Take your list, bring each of these situations to mind, and then identify your defaults. You will find them, and likely culprits will be behaviors such as interrupting, becoming aggressive or passive, taking ownership of ideas, micromanaging, and jumping too quickly to negative judgments of others.

Anticipate and plan your overrides: Once you know your defaults, you can give yourself greater control by anticipating and planning ahead before these challenging moments of truth arise. Research shows that if you prepare and plan behaviors in advance and mentally rehearse them, you are 2-3 times likely to succeed in carrying out your plan. So in advance of your difficult end-of-day meeting, if careful listening is your goal — but frequent interruption is your default – rehearse a plan for better listening you’ll have a better chance of overriding your automatic reflexes.

Design your days: Because self-control varies across a day and a workweek, it makes sense to track it and even plan your schedule around it. Why schedule high-conflict conversations before lunch, at the end of the day, or at the end of a tough week when your self-control is likely to be low? If an easy day has unexpectedly become difficult, consider shuffling your afternoon. You may very well avoid letting slip a snide comment you’ve held back or sharing half-baked criticisms that you know deserve more thought.

Too many professionals who are high-performers in their area of work pass through the behavioral situations of their day on auto-pilot, with defaults running the show. By getting to know your defaults and practicing working around them, you can take greater control over your workday and lead yourself and others more productively, moment to moment.

Your Business Doesn’t Always Need to Change

Evolve or die. If it ain’t broke, break it. If you don’t like change, you are going to like obsolescence even less.

By now, the idea that organizations must adapt in order to maintain both relevance and market share in a rapidly changing world is so ingrained that it’s been reduced to pithy sayings. And there are many organizations — from Blockbuster to Kodak, print-only newspapers to pay-phone makers — that no doubt wish they’d followed the advice.

But is constant adaptation always the best policy? Our research indicates it isn’t. Indeed, any company considering an adaptation initiative should first ask itself five questions:

Do your customers really want you to change? The offerings from privately-held Berger Cookies in Baltimore have been the same for 179 years. The company’s continued success shows that people crave consistency. When you taste your favorite cookie, you don’t want to suddenly discover that the recipe has changed.

Will change alienate your base? Earlier this year, executives at Sirius Satellite Radio decided to capitalize on the renewed interest in singer-songwriter Billy Joel by creating a temporary channel dedicated to him and his music. But it replaced one that had played music of the 1930s and ‘40s, prompting those customers who enjoyed classics from the likes of Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and the Gershwins to cancel their subscriptions.

Will you confuse people? If you bounce from one strategy (say, low prices) to another (full service) and back again, people won’t know what you stand for. The recent failures of mass market retailers Sears and J.C. Penney are clear examples of the problem with inconsistency.

What is the cost? When remaking or radically changing your offerings, you must always weigh the risks against the rewards. This is a lesson Starbucks learned the hard way in the late 1990s. To expedite its expansion, the company made several tweaks: For example, it started shipping its coffee in flavor-locked packaging, which was more efficient but also eliminated most of the aroma; it also streamlined store design to gain economies of scale. But the result was “the watering down” and “commoditization” of the Starbucks experience, founder Howard Schultz later reflected. The company struggled, and its stock price fell, until Schultz came back and reversed those decisions.

Will the change make you vulnerable? When you add to, or alter, your offerings, you can open the door to competitors. For example, Cadillac decided to offer a smaller car, the Cimarron, in the early 1980s. The diluted management focus, coupled with the car’s poor sales, hurt the brand and allowed competitors — especially luxury imports — to gain market share.

It’s important to remember that some companies manage to have it both ways – adapting on the periphery to capture new opportunities while also maintaining their existing businesses. Brooks Brothers serves as a case in point. Instead of simply sticking to selling classic clothing, and waiting for outside catalysts (such as the popularity of the fashion in the television show Mad Men) to increase its popularity, the chain innovated around the edges by offering more fashionable accessories — shoes, belts, bags and the like — while leaving its core basically unchanged.

We like this model of adaptation because you haven’t lost much money, time, or management effort if the changes don’t move the sales and earnings needle. Even more important, they will not have damaged how your base sees you. If the changes are well received, you can expand and integrate them, and/or spin them out into a separate store, division or product line.

The point here is simple: Your customers will dictate when and how much to change. Keep asking them what they want (we recommend a formal or informal audit every six months) and keep watching their behavior, since they aren’t always able to articulate their desires. Then change as they do, or just a little bit faster.

Your Ability to Size Up a Face Probably Isn’t Based on Experience

If adults assume that their ability to discern trustworthiness, or the lack thereof, in strangers’ faces is a skill honed over a lifetime, they’re wrong. Children ages 5 and 6 made very nearly the same judgments about the trustworthiness of computer-generated faces as adults, and children ages 3 to 4 were off by just a few percentage points, says a team led by Emily J. Cogsdill of Harvard. People make inferences—right or wrong—about strangers’ characters within 50 milliseconds of viewing their faces, prior research has shown.

The Indispensable Power of Story

Some people have a way of making the complex clear. They know who they are, why they do what they do, and where they want to go. Because they have internalized all this, they are able to sharply crystallize ideas and vision. They speak in simple, relatable terms. And they can get a lot accomplished.

Making your words understandable and inspirational isn’t about dumbing them down. Instead, it requires bringing in elements such as anecdote, mnemonic, metaphor, storytelling, and analogy in ways that connect the essence of a message with both logic and emotion. Almost everyone leading or creating has a vision, but the challenge is often expressing it in ways that relate and connect. Quick, think of some former Presidents of the United States and presidential candidates. Which ones are most memorable? Which ones are most likable? Which ones won? The leaders who stick in your mind are likely the ones who humanize their message and deliver it in ways that connect with everyone at some level, in turn inspiring others to relate to them while better appreciating the mission at hand.

I have enormous respect for poets and writers who are able to touch our souls and enhance our understanding of concepts and ideas by writing simply and straightforwardly. Take, for example, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman — the tale of a tragic hero, Willy Loman, whose fallibility lies in his lack of self-awareness. The play’s enduring power comes from its straightforward telling of the human story — our aspirations and disappointments and how we deal with them. There is something in it for almost everyone to relate to.

In his book The 5 Essentials: Using Your Inborn Resources to Create a Fulfilling Life, anthropologist-turned-entrepreneur Bob Deutsch describes the importance of what he calls “self-story”:

There is much to be learned from the lessons that fictional characters and their creators teach us… All of our lives have stretches filled with the rising and falling action of a well-plotted story… The best fiction writers capture the core of that. Our most enduring stories and novels live in our hearts because they distill our essences.

I recently read an exceptionally thoughtful but accessible book on wine — The Essential Scratch and Sniff Guide to Becoming a Wine Expert, by Richard Betts. Richard is one of fewer than 200 master wine sommeliers in the world, but instead of speaking of wine in professorial tones he conveys the simple message that nearly every wine’s attributes can be summed up by three things — fruit (red fruit or black), wood (oaky or not), and earth (soil, floral, or “funk”). I’m a longtime wine enthusiast, and this was the first time I’d read a book on the subject that so simply distilled how to think through the smell and flavor of a wine. It made the subject much more accessible, understandable, and enjoyable by bringing structure and and common language to something elusive. Betts’ book is now one of my favorite gift books, and a go-to reference alongside my Robert Parker wine guides.

In my day job as a venture capitalist, I also look for stories I can connect to — in this case the human stories behind the entrepreneurs who are looking for investors. Often the more important questions to ask are things such as, How did this person grow up? What were their past successes and struggles? Why is it that they really want to pursue this big idea? What is their underlying purpose? The answers to these types of questions are what often determine whether we will back an entrepreneur or not. It’s not the facts of the presentation that matter most, it’s the person and the way that person shares his or her story and how that fits with our fund’s objectives. Heart, guts, and the ability to connect are critical in the early stages of company creation and beyond. The durability or effectiveness of any leadership or partnership requires this ability to connect and share a story — people need to just feel it.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers