Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1436

April 22, 2014

The One Thing Every Business Dies Without

George Carlin always called people on their BS. He once railed against the idea of “saving the earth,” pointing out that the Earth will be fine with or without us. “The planet isn’t going anywhere. We are! … The planet’ll shake us off like a bad case of fleas.” All that would be left of us, he said, was maybe some Styrofoam.

The idea that the earth needs humans to thank it and care for it is kind of funny. So Earth Day is kind of a quaint idea. And also strange to think that we might only value the spinning ball we’re totally reliant on for a single day each year. Imagine if you only appreciated your mother on Mother’s Day, or your significant other on Valentine’s Day. It would not bode well for your relationships.

As many pundits will point out every year at this time, we need to value Earth every day. And that’s even more so for the business community. But we shouldn’t thank the version of “Earth” used for show, pictured on glossy corporate citizenship reports, or the theoretical one that many people seem to think only exists in national parks we go visit. No, business needs to value the Earth like it does its balance sheet. The planet provides the collective assets on the balance sheets of our global economy: that is, it’s quite literally the giver of everything required for our economy and society. It’s almost absurd to have to say this, but without a planet, there is no business.

While this appreciation should infuse all our days, it is useful to take this one day and focus our thinking. It’s a good time to stop and analyze specifically what underpins your business. You’re likely doing something like this regularly anyway – one of those retreats with executives, facilitators, and sticky notes to think through business strategy, think “outside the box,” co-create, or whatever is hot in brainstorming that year.

So take a day this week to think hard about how the planet underpins the business, and how your company and sector should deal with that reality. Consider three steps. First, ask some leading questions: What do climate change and extreme weather mean for your business, your customers, and your supply chain? How do growing resource constraints like water shortages, or rising commodity prices, affect your value chain and your margins?

Then paint some pictures and scenarios of sectors under pressure already: Consider what food and agribusiness businesses are going through dealing with ongoing drought in California. Or think about the choice forced on apparel makers and retailers by a 300% rise in cotton prices over one recent 2-year period: either pass along higher costs and reduce sales, or take a hit to margins. Then ask yourself what could happen to your sector to shake things up this much.

Finally, ask some heretical questions. Could we operate without fossil fuels and only renewable energy, or without using water? (Companies like Apple and IKEA are already well on their way to 100% renewables.) What if we tried to build a circular economy and took back everything we sold at the end of the product’s life? How could we fundamentally change how our business operates to navigate and profit from the pressures we’re facing?

Understanding these scenarios and realities, and preparing for them, is now a critical skill for business success. But how many companies use Earth Day (or any day) that way? Very, very few. For most of the last 44 years, most companies have spent Earth Day – if they acknowledge it at all – planting some trees or announcing some nice (but small) initiatives that protect some land or support environmental causes. Those are lovely philanthropic choices. And to be fair, companies are increasingly announcing much larger moves, like IKEA’s recent purchase of a wind farm to supply 165% of the electricity needed by its U.S. operations.

But most companies clearly miss the point of what “Earth” really means to business. The planet – with all the metals, fiber, food, air, water, and stable climate it provides – is required for our existence. So ensuring that this stream of support continues, or that the asset base stays healthy, needs to be the first priority for society and business. As the founder of the UK’s Forum for the Future, Jonathan Porritt, has written, “Not only is the pursuit of biophysical sustainability nonnegotiable, it’s preconditional.” I love the startling, brutal simplicity of that word preconditional. In other words, if we don’t protect the assets on the balance sheet of the world, we go bankrupt and stop functioning.

So today let’s not call it Earth Day. How about “Fundamental Underpinnings of Our Business’s Existence and Success Day.” It’s not as catchy, but it is more accurate.

April 21, 2014

To Create Change, Leadership Is More Important Than Authority

Aspiring junior executives dream of climbing the ladder to gain more authority. Then they can make things happen and create the change that they believe in. Senior executives, on the other hand, are often frustrated by how little power they actually have.

The problem is that, while authority can compel action, it does little to inspire belief. It’s not enough to get people to do what you want, they also have to want what you want — or any change is bound to be short lived.

That’s why change management efforts commonly fail. All too often, they are designed to carry out initiatives that come from the top. When you get right down to it, that’s really the just same thing as telling people to do what you want, albeit in slightly more artful way. To make change really happen, it doesn’t need to be managed, but empowered. That’s the difference between authority and leadership.

In the 1850’s, Ignaz Semmelweis was the head physician at the obstetric ward of a small hospital in Pest, Hungary. Having done extensive research into how sanitary conditions could limit infections, he instituted a strict regime of hand washing and virtually eliminated the childbed fever that was endemic at the time.

In 2005, John Antioco was the eminently successful CEO of Blockbuster, the 800-pound gorilla of the video rental industry. Yet, despite the firm’s dominance, he saw a mortal threat coming in the form of online streaming video and nimble competitors like Netflix. He initiated an aggressive program to cancel late fees and invest in an online platform.

Things ended poorly for both men. Semmelweis was castigated by the medical community and died in an insane asylum, ironically of an infection he contracted while under medical care. Antioco was fired by his company’s board and his successor reversed his reforms. Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2010.

While today the insights of Semmelweis and Antioco seem obvious, they did not at the time. In the former case, it was believed that illness was caused by an imbalance of humors and in the latter, the threat of online video seemed too distant to justify forsaking short-term profits. Even given their positions of authority, neither was able to overcome the majority view.

We tend to overestimate the power of influence. It always seems that if we had a little bit more authority or had more data to back us up or were able to make our case more forcefully, we could drive our ideas forward. Yet Semmelweis and Antioco had not only authority, but also had the facts on their side and were willing to risk their careers. They failed nonetheless.

In the 1950’s, the eminent psychologist Solomon Asch performed a series of famous experiments that help explain why. He showed the chart below to a group of people and asked which line on the right matched the line on the left.

It seems like a fairly simple task and it should be, but Asch, renowned for his ingenuity, added a twist. All of the people in the room, except one, were confederates who gave the wrong answer. By the time he got to the last person who was the true subject, almost everyone who participated conformed to the majority view, even though it was obviously wrong.

While we like to think of ourselves as independent and freethinking, the truth is that we are greatly affected by the views of those around us. If you are in an office where people watch silly cat videos, you’ll find yourself doing the same and laughing along. Yet often you’ll find that they’re not nearly as funny when viewed in different company.

Yet conformity is never absolute. Even in Asch’s experiments, there were some who held out, much like Semmelweis and Antioco. We all have our points of conviction on which we are unlikely to be swayed, other areas in which we need more convincing and still others that we really don’t care enough about to form much of an opinion at all.

That essentially is what the threshold model of collective behavior predicts: Ideas take hold in small local majorities; many stop there and never go any further, but some saturate those local clusters and move on to more reluctant groups through weak ties. Eventually, a cascading effect ensues.

The best-known example of the threshold model at work is the diffusion of innovations model developed by Everett Rogers, in which a small group of innovators gets hold of an idea and indoctrinates a somewhat more reluctant group of early adopters to form local majorities. The reticent denizens of those clusters find themselves outnumbered and begin to conform, just as in Asch’s study. Before long, the new converts find themselves passing the idea on to other social groups they belong to. The process continues until the idea has grown far beyond its original niche. Eventually, even the most skeptical laggards join in.

Now we can see the failure of Semmelweis and Antioco – and the folly of so many aspiring executives — for what it is. Rather than seeking to lead a passionate band of willing innovators and build a movement, they leaned on their authority to create wholesale change by forcing the unconvinced against their will. Instead of painstakingly building local majorities, they attempted to compel entire populations.

Control is an illusion and always has been an illusion. It is a Hobbesian paradox that we cannot enforce change unless change has already occurred. Higher status—or even a persuasive presentation full of facts—is of limited utility. The lunatics run the asylum, the best we can do as leaders is empower them to run it right.

And that’s why change always requires leadership rather than authority. Respectable people always prefer incumbency to disruption. Only misfits are threatened by the status quo. So if you want to create real change, it is not power and influence that you need, but those who seek to overthrow them.

Why You Have to Generate Your Own Data

This is it. You’ve aligned calendars and will have all the right decision-makers in the room. It’s the moment when they either decide to give you resources to begin to turn your innovative idea into reality, or send you back to the drawing board. How will you make your most persuasive case?

Inside most companies, the natural tendency is to marshal as much data as possible. Get the analyst reports that show market trends. Build a detailed spreadsheet promising a juicy return on corporate investment. Create a dense PowerPoint document demonstrating that you really have done your homework.

Assembling and interpreting data is fine. Please do it. But it’s hard to make a purely analytical case for a highly innovative idea because data only shows what has happened, not what might happen.

If you really want to make the case for an innovative idea, then you need to go one step further. Don’t just gather data. Generate your own. Strengthen your case and bolster your own confidence – or expose flaws before you even make a major resource request – by running an experiment that investigates one or a handful of the key uncertainties that would need to be resolved for your idea to succeed.

That may sound daunting if you haven’t tried it. And, you may well ask, how do you do it when you lack a dedicated team and budget? Fortunately, there’s a fairly systematic way to go about it.

Start by focusing your attention on resolving the biggest question on the minds of the people who will decide to give you those resources. That might be whether a customer will really be willing to use – and purchase – your proposed offering. Or perhaps whether the idea is technologically feasible. Or maybe there’s concern that some operational detail could stand in the way of success.

Once you’ve identified the most important potentially “deal-killing” issue, the next step is to find a cheap and quick way to investigate it. The key here is to find some low-cost way to simulate the conditions you’re trying to test.

For example, for several years Turner Broadcasting System (a division of Time Warner) had been playing with the idea of tying the first advertisement in a commercial break to the last scene in a television program or movie. Imagine a scene of a child landing in a mud puddle followed by a commercial for laundry detergent. Academic research showed this contextual connection had real impact, raising the possibility that Turner could charge a highly profitable premium to match the right advertiser to the right commercial slot. But would the system it used to match its content to advertisers’ offerings be too expensive to make the service profitable? And what if there just weren’t enough scenes in Turner’s library of movies and TV programs that could serve as effective contexts for its advertisers? How could the project team find out?

Instead of speculating, Turner locked a team of summer interns in a room for a few weeks, had them watch movies and television shows, and asked them to count the number of points of context in a select group of categories. Then Turner brought the results to a handful of advertisers, who enthusiastically supported the idea.

Imagine how these experiments changed the meeting. Without them, the team would have presented a conceptual plan full of glaring unknowns. But with these data in hand, they could offer evidence that the idea was feasible and that potential advertisers were interested. Perhaps not surprisingly, Turner ended up launching the idea, named TVinContext in 2008 to significant industry acclaim.

Working out how to generate data to test out an idea at its earliest stages requires some creativity. A mobile device company we were advising was considering a new service that would serve up customized content to consumers based on their mood and location. Would anyone want that? Would they pay for it?

To find out, we had to find a low-cost way to simulate the offering and some way to test people’s interest in something that didn’t actually yet exist. First we worked with third-party designers we contacted through eLance.com to develop mockups of what the interface might look like and worked up a two-minute animated video describing how the service would work. Here’s a screenshot from the video:

How could we tell whether the idea resonated with customers? Of course we could show them the mockups and videos and ask them if they liked or didn’t like the idea. But that really wouldn’t tell us whether they liked it enough to use it, let alone pay for it. So we asked customers at the end of the presentation if they wanted to be the first to participate in a beta test of the idea. All they had to do was give us their credit card number, and we’d charge them $5 once the test started. We didn’t actually plan to charge the consumers. Instead, we wanted to know how many were interested enough in the service to part with sensitive data in the hopes that they’d be first in line to access it when commercial trials began. When a significant number of customers were willing to give us credit card details, we knew we were going in the right direction.

One of the most valuable things these kinds of experiments can do is provide dramatically convincing evidence of serious flaws in your idea before you make the mistake of investing serious resources in it. The results from one concrete demonstration is worth reams and reams of historical market data.

For instance, an education company had what at first looked like a really promising idea to improve the quality and efficiency of teacher recruiting. Schools and applicants have long complained that paper résumés aren’t very good indicators of teaching ability and interpersonal skills. What if, the company wondered, we created a service that allowed schools to review short video clips created by prospective teachers showing them in action? Both teachers and schools loved the concept — on paper.

But then the education company tried to get real teachers to create real videos. It advertised the service in a handful of teacher-training colleges and put posts on on-line forums about the service. No interest. The company even began offering $100 for people to sign up. Still no interest.

It turned out that once the opportunity shifted from abstract to real, prospective teachers clammed up. They loved the concept of selling themselves through video, but in reality worried about how they would come across.

Notice how all of these examples involved some kind of prototype. As online tools improve and 3D printing becomes increasingly affordable and accessible, it’s becoming easier and easier to bring an idea to life without substantial investment. For example, a company that manufactures insulin pumps for people who suffer from Type 1 diabetes knew that customers didn’t love the physical designs of current pumps. The company was curious to find out how patients would react to pumps of different sizes and shapes. It worked with a small design shop in Rhode Island to develop a series of physical prototypes that brought the look, feel, and weight of the imagined devices to life. It had insulin pump customers pick up and play with the prototypes and compare them side-by-side with current offerings. The approach allowed the company to get critical feedback before it invested millions in more comprehensive design work.

None of the experiments described above required hundreds of thousands of dollars or hundreds of man hours. And yet they all quickly generated critical data that helped innovators to strengthen – or, in the case of the education company, discard – ideas. When it comes to making your case persuasive, one well-thought out experiment is worth a thousand pages of historical data. Certainly that’s well worth a little extra effort.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How to Have an Honest Data-Driven Debate

The Quick and Dirty on Data Visualization

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious

Even Good Employees Hoard Great Ideas

One of the most heated debates involving innovation revolves around how to best incentivize people to develop and implement new ideas. Research on this issue offers a wide range of conclusions. For example, one recent research report suggested that offering financial incentives only raised the number of mediocre ideas and had little impact on breakthrough innovation. On the other hand, an MIT study concluded that group incentives and long-term rewards do have a positive impact on innovation. And still another survey of 20 companies from different industries found that 90% of the respondents thought that incentivizing and rewarding innovation was “something we should be doing better.”

Driving this debate is the fear that employees will not develop and bring forward creative ways to improve the business unless they are given something “extra,” like time, resources, ownership, or money. For example, one manager recently told me about an employee who refused to share her innovative solution with anyone in the firm unless they would sign a non-disclosure agreement to prevent colleagues from running off with “her idea.” An executive in a different company described a situation where the owner of a particular database would not allow it to be used by another business unit unless his team was given a portion of the revenue.

Creating financial incentives for innovation does not necessarily prevent these kinds of issues. In fact, focusing too much on “cash for ideas” may open a Pandora’s Box of unintended consequences — people innovating for their own benefit instead of the company’s, competition arising between individuals or units, employees losing focus on current business, and so on.

This is not to say that there is no place for financial incentives for innovation, but it usually takes a lot of hard work to get them right.

What most companies should focus on first is creating an environment, or a culture, that fosters innovation. For example, in the case of the employee wanting an NDA before sharing her idea, the underlying issue may not have been money, but rather commitment and trust. For some reason, this employee didn’t feel that part of her job was to help the company come up with new ways of working, and she wasn’t excited about helping the company improve; she was only innovating because it was good for her. At the same time, she didn’t trust her manager or colleagues to explore or implement her idea, because she was afraid that she wouldn’t be recognized for her contribution. Paying her for the idea likely wouldn’t resolve these issues; rather, it might reinforce them.

Similarly, in the example involving database ownership, the manager seemed to feel that the database belonged to him (and his business unit) and not to the company. He felt that his team should therefore be compensated for its use by another unit. Giving in to this demand with a monetary reward could confirm this belief and further constrain sharing and collaboration in the future.

Unfortunately, while it’s easy to talk about creating an innovation-friendly culture, it’s hard to do. But here are three ways to get started:

First, educate your people about what innovation means for your business. Particularly in companies that have experienced years of efficiency management, innovation can be seen as just another way to reduce costs and get rid of people – which can exacerbate the defensive “me-first” behavior that is antithetical to real innovation. So take time to talk about the importance of finding new solutions for customers, competing with start-up competitors, ramping up internal growth, or whatever other rationale makes sense for your company.

Second, build innovation into your goal-setting and performance management process, with as much specificity as possible. If you want employees and managers to innovate, then make it clear what that means, how it’s measured, and how it needs to be part of their jobs — not something “extra” to be done in their spare time.

Finally, find some early examples of innovation, where people did the right things, and either got good results or quickly learned from their failures. Publicize and communicate these situations, give the people involved recognition, and make it clear that this is the kind of behavior that’s needed and wanted.

Turning a traditional company into an innovation machine won’t happen overnight. But if you focus on culture rather than just cash, you’ll probably have a better chance of success.

Study: Female Executives Make Progress, But Mostly in Support Functions

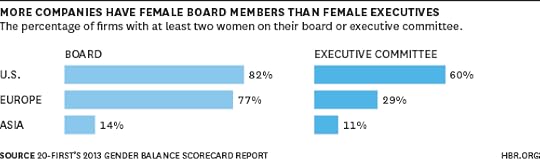

Sixty percent of the top U.S. companies now have at least two women on their executive committees. Eight companies (including IBM, Pepsico, Lockheed Martin and General Motors) have a woman CEO. But closer inspection shows there’s a long way to go.

My gender consultancy firm, 20-First, has just published its annual Gender Balance Scorecard (pdf) of the top 300 companies in the world across the US, Europe and Asia. As usual, we try to broaden the focus from the current buzz around corporate boards to the more relevant metric of the gender balance of executive committees.

By focusing on the top management of a company – people who have worked their way to the top and have executive responsibility for its results – the report offers a clear picture of the attitudes and environments that companies have built – or haven’t – to gender balance their leadership teams.

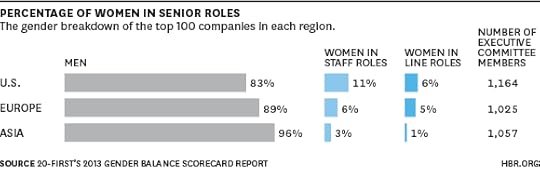

Of the 1,164 executive committee members of America’s Top 100 companies, the ratio is still 83% men to 17% women. And two thirds of these women are in staff or support positions (65%) such as HR, Communications or Legal. Only 35% are in line or operational roles – and there has been no significant change in these percentages over the last three years.

Meanwhile, Europe’s companies, while progressing on Board balance in some countries because of quotas (or the threat of them), are still struggling to balance their executive teams. Less than a third (29%) of European companies have at least two women on their Executive Committees. However, this is better than the 20% in 2011. None have a female CEO. Of the 1,025 executive committee members of Europe’s Top 100 companies, the real story is the continued and absolute (89%) dominance of men. Of the 11% that are women, the majority (58%) are in staff or support roles, a tiny bit better than the 65% in the US.

Asian companies lag far behind their Western counterparts. The top Asian (including Australian) companies are still the preserve of men. The vast majority (89%) of companies have less than two women on their leadership team. Of the 1,099 members of Executive Committees, 96% are men. Of the 42 women who are sprinkled among them, two thirds of them are in staff roles.

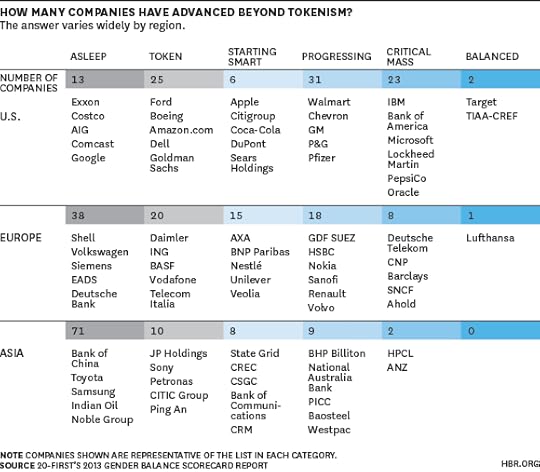

To determine these ratios, the survey tracks companies along six phases of the gender journey:

Asleep – Some companies haven’t even started the journey; we put them in our ‘Asleep’ category. These companies are still, in 2014, pictures of imbalance. They are run by an exclusively male team.

Token – Less than 15% of both genders on the Executive Team. In this category, the individual(s) is in a staff or support function rather than a line or operational role.

Starting Smart – These firms also have less than 15% of both genders in the mix, but they are in a central core or operational role, sometimes even CEO.

Progressing – These companies have reached a minimum of between 15% and 24% of both genders on their top team.

Critical Mass – These are companies that have achieved a balance of at least 25% of both genders, but less than 40%.

Balanced – The rare companies that have achieved gender balance, with a minimum 40% of both genders on the Executive Team. This is where balance at the top begins to reflect the reality of 21st century customers, leadership and talent and gives companies the competitive edge to innovate and deliver value sustainably and globally.

You really have to search hard for signs of progress in the gender-balance journey at Balanced levels. Only nine well-known companies are now run by women out of 300.

The differences across geographical regions show the impact of national culture on the prioritization of gender balance. This is less true by sector; the most balanced companies cover a range of sectors.

Leadership is the key variable in improving the balance at the top. The companies that have become balanced or achieved critical mass have been proactively adapting their corporate cultures and mindsets to the 21st century. We salute their success. And hope it will offer good role models to the rest.

China Shows a Decline in Workers’ Share of Economic Output

In many industrialized areas in China, the labor force’s “share” of GDP, meaning the proportion of provincial output that is distributed as wages, rather than going to capital and government, fell between 1997 and 2007, say Wei Chi of Tsinghua University and Xiaoye Qian of Sichuan University. For example, in Guangdong, it fell from 49% to 39%; in Chongqing, from 57% to 48%; and in Sichuan, from 56% to 46%. Past research has shown a connection between low labor share and widening inequality in China. Moreover, a low labor share poses problems for China’s goal of transforming its economy to rely on consumption rather than exports.

Don’t Let Incumbents Hold Back the Future

Like many other people, I thought the (thankfully temporary) decision by the French Council of State to force Uber and other app-based car summoning services to bake in a 15-minute delay, so as not to compete unfairly with taxis, was a classic example of Eurosclerosis, of Gallic dirigisme run amok, and lots of other bad and un-American things.

But then I read James Surowiecki’s recent column about the regulatory barriers that geek chic car company Tesla is facing as it tries to set up its own showrooms in New Jersey and many other states, and I became a lot less confident that we in the U.S. are doing a great job of letting innovation flourish without counterproductive meddling and stonewalling.

Surowiecki quotes Yale economist Fiona Scott Morton as saying that “There isn’t a rational argument for why a new company should have to use [existing] dealers. It’s just dealers trying to protect their profits.” So why is it the case in 48 states today that “direct sales by car manufacturers are restricted or legally prohibited, and manufacturers are often prevented from opening a dealership that would compete with existing ones?” Because that’s how today’s auto dealers want it, and they’re organized and affluent enough to sway the lawmaking process. Opensecrets.org, for example, lists the National Auto Dealers Association as #19 in its list of ‘Top All-Time Donors’ to candidates, parties, and leadership PACs.

The dealers say that they couldn’t compete if the car manufacturers were allowed to sell directly to consumers (the examples of successful dealers in countless other industries evidently give them no confidence or playbook) and that they’re standing up for “family-owned businesses.” But ‘family-owned’ definitely doesn’t mean ‘small’; in Texas, for example (the stage for another battle involving Tesla), a prominent political contributor is a billionaire who “owns the world’s second-largest Toyota franchise and operates in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas.”

Whether or not you care about Uber and Tesla, you should care about business innovation and disruption because they’re a primary way that progress happens and that people become better off over time.

Incumbents, of course, don’t want to be disrupted. And they’ll throw up all manner of barriers and smoke screens to try to prevent it from happening. They’ll enlist politicians, regulators, PR agencies, and everyone else they can think of to help with their campaigns to maintain the status quo.

They’ll do this all over the world, even in innovation-friendly countries like the U.S., and they’ll do it more and more often as we head deeper into the second machine age and the scale, scope, and pace of technology-based innovation and disruption pick up.

They’ll work hard to, as my friend Tim O’Reilly puts it, protect the past from the future. We should work hard to oppose this trend, and to protect the future from the past. A first step in this work is to be skeptical of claims from incumbents that when they protect themselves from upstart disruptors they’re also helping us out. Most of time, they’re not.

April 18, 2014

Can Charisma Be Taught?

Olivia Fox Cabane is an introvert who was an outcast in school. Today she earns six figures teaching people, mostly up-and-coming Silicon Valley leaders, how to be charismatic. Her story is not only an inspiring one of adapting self-help narratives and neuroscience to "trick" her own mind; it’s also a tale couched in almost a century of management thinking about who can and can't be a leader. Sixty years ago, Matter's Teresa Chin writes, "somebody like Olivia would have been better off seeking a profession in which she could mostly avoid people." It was, in part, the rise of the technology industry that gave charm a new urgency, because tech companies needed managers on the inside who were "technical and charismatic." Indeed, "perhaps only in Silicon Valley would a group of engineers think they could hack their way to charisma with a series of neuroscientific shortcuts."

Where the Heart IsHow a Chinese Company 3D-Printed Ten Houses In a Single DayBusiness Insider

3-D printers are most often thought of as small, personal replacements for large, industrial manufacturing machinery. But a number of researchers and private companies are taking the opposite tack, exploring applications that require constructing 3-D printers on a massive scale. Researchers at the University of Southern California have built a printer that can create a house in 24 hours, laying out a concrete structure according to a programmed pattern. In Amsterdam, Dutch architects are constructing a 13-room house from 3-D printed Lego-like plastic blocks. Now the Chinese firm WinSun Decoration Design Engineering has built a truly massive 3-D printer – 500 feet long, 33 feet wide, and 20 feet high – to produce entire neighborhoods, printing out the parts needed to build 10 homes in 24 hours from concrete produced out of recycled materials. Envisioned as housing for the poor or displaced, the homes are sturdy and, at $4,800 a piece, radically cheap. –Andrea Ovans

Beware the Tentacles This Is How Bureaucracy Dies Fortune

Gary Hamel says it's disheartening to go inside "one of America's youngest and fastest growing IT companies" and find that it already has 600 vice presidents, a pretty strong indicator that the "tentacles of bureaucracy" are rapidly encircling it. He doesn't say which young, fast-growing company he's talking about, but I guess it doesn't matter. He takes aim at every company where the ratio of managers to frontline employees is rising, where decision cycles are getting longer, where cliques of managers are accumulating more and more power, where rules are proliferating, and where "legal has to sign off on everything." This is how opportunities to be nimble and innovative are squandered, he says, and how companies become irrelevant. In Hamel's view, every company should be like the internet: decentralized, non-bureaucratic, flexible, and empowering. Companies should value initiative, innovation, and passion, he says, over obedience, diligence, and, yes, even expertise. –Andy O'Connell

Sleeping on the FloorWhy One Polish MP Is Working as a Handyman in London Christian Science Monitor

When the European Union expanded 10 years ago to include Poland and nine other countries, the UK expected an influx of Polish workers, but it was caught off guard by the size of that influx. An estimated half million Poles have migrated to Britain, and a Polish member of parliament, Artur Debski, came to London recently to find out for himself what draws his countrymen and what it's like for them to scrounge for work in the United Kingdom. He slept on someone's floor, got rejected when he tried to open a bank account, and finally landed a temporary job that requires a 43-minute commute. But he can see the appeal of it. Despite all the hardships, life in Britain is more alluring than trying to get by in Poland, with its shortage of opportunities and lack of freedom. The moral of the story is stark: "This is a big problem for my country," Debski says. "We are losing the young people who are our future." –Andy O'Connell

Good Signs? Microsoft's New CEO: Adding What Was MissingDatamation

When IBM touts its products, it presents testimonials from real customers. When Microsoft showcases its products, it relies on hypothetical companies as examples, maybe because the people who design Microsoft products often don’t use them or ever see anyone else using them. That may change under new CEO Satya Nadella, says Rob Enderle in this smart take on early signals coming from Microsoft’s new management. At his first major presentation, Nadella distinguished himself from Steve Ballmer by yielding the floor to his division leaders, a deft way to send a message that the company won't be bounded by the limits of its chief executive. Even more telling, Enderle argues, is that the executive presenting Microsoft’s data analytics offerings was COO Kevin Turner – not an engineer, but an end user. –Andrea Ovans

BONUS BITSYour Week in Tweets

How a Middle-Aged IT Guy from Peoria Tweeted His Way Into a Writing Job on Late Night With Seth Meyers (Vulture)

Treat, Don't Tweet: The Dangerous Rise of Social Media in the Operating Room (Pacific Standard)

The Naked Truth About US Airways' Social Media Policy (U.S. News and World Report)

Why Entrepreneurs Will Beat Multinationals to the Bottom of the Pyramid

C.K. Prahalad and Stuart Hart’s seminal book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid gained a wide audience when it was published in 2004 and has continued to be widely read ever since. Its iconic phrase, “bottom of the pyramid,” entered the English lexicon. The book was a call to action to the world’s largest companies to develop new products for the four billion people living on $4 a day or less—a market representing what was in effect the new frontier for corporate expansion.

What was the result of this stirring cry a decade ago?

On the fifth anniversary of the book’s publication, Professor Prahalad was interviewed by Knowledge@Wharton. He was asked “what impact have your ideas had on companies and on poor consumers?” Prahalad asserted that the impact had been “profound,” citing the $200 laptop computer, the spread of cell telephones, and Kenya’s M-PESA text- messaging funds transfer service. But the concept of the $100 laptop was a project that emerged from MIT, not a large company, and was judged a failure; cell phones spread rapidly through developing countries was a result of local entrepreneurship, not multinational initiative; and M-PESA was a Kenyan innovation.

Five years further along, there is scant evidence that multinational corporations have expanded any further into the bottom-billions market. We believe they’re unlikely to do so, and that entrepreneurs working solo or in teams are far better positioned to go serve these customers. The reason is that multinationals face the constant temptation to apply their substantial resources to extend the reach of their existing businesses, rather than starting from scratch. Entrepreneurs, by contrast, start from scratch almost by definition. For reasons we’ll describe, that approach is essential to successfully serving the bottom of the pyramid.

The tendency for too many multinationals is to design products for the bottom of the pyramid by stripping features from existing products. But this approach seldom works. In our experience, products and processes must be designed not merely to reduce prices by, say, 30% below developed world prices, which might be achieved by removing features; success requires prices close to 90% less. As you can imagine, this puts pressure on product design, and this focus has become the centerpiece of “zero-based design” which seeks to build inexpensive products from the ground up. Entrepreneurs, unconstrained by pressure to expand existing brands and product lines, are better positioned to utilize this approach.

This zero-based design approach also avoids a reliance on preexisting business models. One of the greatest challenges at the bottom of the pyramid is “last mile” distribution. A large number of the world’s poor live in villages without much infrastructure. Delivering products in this environment adds to the cost, making it further unlikely that preexisting product lines can be tweaked and brought to market successfully. By designing products from the ground up, entrepreneurs are better positioned to consider the challenges of distribution early on, and account for them in their products and business model.

Moreover, most multinational corporations are, inevitably, bureaucratic enterprises riddled with barriers to doing things differently. If someone far down the chain of command does devise a great solution to a problem the company had never before considered, it’s a fairly sure bet that his idea will be vetoed somewhere up the line. (Remember the two guys named Steve who took their idea for a personal computer to HP? Whatever happened to them?) The difficulty is compounded if the proposed project requires a wholly fresh approach to design, marketing, and distribution and must be carried out in an exotic locale in an unfamiliar language and confounding culture. Somewhere up the ladder in the corporate hierarchy, someone is sure to balk.

Finally, success in nascent markets requires a commitment to agility and constant refinement. This means not only tweaking products, but everything about the business. Here again, entrepreneurs are able to incorporate their learning more quickly, as opposed to multinationals whose teams often have to run changes up the flag pole.

For all these reasons we believe it will be new companies more than old ones that help those living on a few dollars a day move out of poverty. Of course, we’d love to be proven wrong – there’s certainly plenty of room at the bottom of the bottom of the pyramid for experimentation and collaboration. For companies of any size serious about these markets, it is critical to remember that lessons learned selling to richer consumers likely do not apply.

Midsized Firms Can’t Afford Bad Bets

CEOs of midsized companies who make big bets can lose the farm. The executives of Fortune 500 companies might be able to lose the same bet with impunity, and the founders of venture capital-funded startups are only renting the farm (with the VC’s money) anyway. But for a midsize company, an ambitious investment that you don’t have the wherewithal to execute on can be fatal.

These travails don’t just happen to declining midsized firms making the business equivalent of a Hail Mary pass. In fact, rapidly growing midsized companies are even more vulnerable to running out of cash while gunning for growth than are shrinking firms. Even what appears to be a small investment risk can turn into a big one, especially when information technology comes into play.

That was the case at a toy importer that was pressing the growth pedal to the metal. The company was hell-bent on entering a new market but knew it had to automate its warehouse to do so. Warehouse automation systems are big and complicated; if they don’t work, you’re worse off than before since it becomes almost impossible to ship product. Unlike a Fortune 500 company that can spend tens of millions of dollars on external consultants to help implement such a system, this company was stingy with its IT dollars. It put one of its executives in charge of the project and told him to team up with the head of IT, even though neither had ever run a project this large or complex.

The project budget paid for the software and not a lot more. The timeline was unrealistic, so the installation took a month longer than planned. And when the company did the cutover – right before its customers’ biggest selling season – the system just . . . didn’t . . . work. The malfunction caused major delays shipping toys to retailers. Not surprisingly, many of those retailers refused to pay when the toys finally did arrive, too late for the holiday season. The importer lost millions of dollars and began running out of money. Its growth had been derailed.

This particular toy importer violated every one of the rules that govern the success of a midsize company’s strategic initiative: It gave an unproven team an unrealistic budget and asked it to do a highly technical, risky, but mission-critical job without strong external partners or a proven implementation process.

In contrast, one California manufacturer of data storage equipment grew by making a much less reckless bet. BlueArc was venture-funded, but in 2008 VC money was getting hard to find. (The chill winds of the Great Recession were blowing through Silicon Valley, too.) BlueArc’s devices were high-end, but its management believed it needed a mid-priced product to get it through the recession. However, cash flow from operations had shifted from positive to negative, the company’s cash pile was dwindling, and the new product would demand R&D investment.

BlueArc’s top team remained confident because they knew the company was strong in three critical areas:

The ability to predict the market. BlueArc’s CFO, Rick Martig, and other executives gathered market data to support the investment in the mid-tier data storage product. Poring through the IPO documentation of several larger competitors that had introduced similar devices, they produced a set of financial data that showed the growth and profitability of competing products. That helped BlueArc raise another $28 million in VC funds. Then it cut general and administrative expenses and sales staff to contain operating losses. The company’s leaders promised the board of directors (largely, their VCs) they would make further cuts in areas not related to the new product if the company fell short of its sales and profit targets.

Their ability to execute. The R&D team that had brought the company’s successful higher-priced data storage system to market had no doubt that they could pull off a lower-priced version. Blue Arc’s R&D had a track record of success; it was a proven team.

Forecasting acumen. Martig was a seasoned CFO with years of forecasting experience in technology firms. He knew where the surprises would come from, and he built them into the forecast.

BlueArc’s new product hit the market and was an instant success. The company achieved its forecasts which, after 18 months, enabled it to break even. By 2011, the company revenues were $86 million, and it filed for its own public stock offering. But before that could happen, a much bigger competitor made an offer that the VCs couldn’t refuse, one that was a strong multiple of revenue.

Like the toy importer, BlueArc made a major investment risk: developing and launching a new product while cash was dwindling. But the difference was that BlueArc’s bet was highly informed and far better executed than that of the toy importer.

It had to be. Most midsize companies – especially those that aren’t VC-funded – never recover from ambitious investment bets gone bad.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers