Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1437

April 18, 2014

Your Tendency to Put Things Off May Have Been Inherited

46% of the trait of procrastination is due to genetic influences, according to a study of hundreds of sets of twins. The research also lends support to a theory that procrastination, in its tendency to undermine adherence to long-term goals, is a byproduct of impulsivity, which may have had an evolutionary origin: Hunter-gatherers had an advantage if they acted swiftly to satisfy their survival needs. Your genetics don’t necessarily condemn you to a life of procrastination: The 46% figure means procrastination is only “moderately heritable,” according to the researchers, led by Daniel E. Gustavson of the University of Colorado.

Privacy Is a Business Opportunity

Technology innovation and the power of data analytics present tremendous value, but also new challenges. While a digital economy requires businesses to rethink priorities and practices, this doesn’t have to be a burden. Instead, privacy protection should be a practice as fundamental to the business as customer service. Privacy is an essential element of being a good business partner. It may take time for this idea to sink in at the highest executive levels of some companies, but the conversation is advancing rapidly after a number of recent high-profile data breaches.

Consumers are now not only second-guessing the security of their personal information when they make routine shopping trips, but are also extending this lack of trust to how they perceive the stores and brands they once preferred. Discussions of privacy and security policies are now happening in boardrooms across the globe, and many of these conversations are zeroing in on what should be done to integrate privacy as an added value to the business.

The added value of privacy is intrinsic no matter where your company sits in the digital economy. From consumer goods manufacturers to healthcare services entities, any business will benefit from proactively tackling privacy issues in one of three primary ways: protecting your brand, offering a competitive advantage from integrating privacy and security features into products and services, and creating new products and services designed to protect personal data.

There have been many breakdowns in security or privacy causing significant, and even irreparable, damage to companies’ reputations. For context, Young & Rubicam (Y&R) estimates that brand value represents nearly one-third of the $12 trillion in market capitalization of the S&P 500.

Y&R evaluates brands on four pillars of health, one of which is esteem – the respect, regard and reputation that fulfill the promise of the brand. Most businesses, passively or actively, spend years earning the trust of their customers, partners, employees and shareholders, all of whom contribute to financial stability and growth. When an incident related to privacy occurs, it is a direct blow to the brand’s esteem and its financial value.

OfficeMax learned this lesson the hard way when last year they sent a direct mail advertisement to a potential customer, Mike Seay. Inadvertently, and through the use of a data broker, the mailing was addressed to “Daughter Killed in Car Crash or Current Business.” Just a year earlier, Mr. Seay’s daughter had in fact died in a tragic auto accident. The mailing made global news with some calling the letter a “gross insensitivity,” “tragic incompetence” or “bewildering stupidity” on the part of OfficeMax. In response, OfficeMax replied that the information came from a third-party data broker and they did not know why this form of address was used, as they had not asked for any such personal information. OfficeMax did not reveal the name of the data broker, but doing so would not have insulated OfficeMax’s brand from harm.

Subsequently, many privacy advocates and regulators have pointed to this example to highlight the need for companies to make privacy a priority. Companies need to pay careful attention to privacy-related activities before an incident like this happens. Attention includes not only putting in adequate control mechanisms to prevent issues, but also building up positive brand associations with privacy and security. There are three main mechanisms to do this, and at Intel we are pursuing all of them.

Gaining a competitive advantage. Companies can gain a considerable edge by focusing on the interests of individuals. At Intel, we focus on the individuals who use the digital devices that use our microprocessors and chipsets. We want to understand how our technology affects peoples’ lives. In our research, we consistently hear that people are hesitant to use technology in new and innovative ways because of privacy and security concerns, specifically for electronic health records and online banking. For Intel’s technology to achieve its maximum potential we need to focus on how to address these concerns and demonstrate those privacy and security controls as a competitive advantage.

Today, privacy is an active area of marketing for the technology industry. Companies compete on the basis of how long they retain personal data, whether they share data with third parties, the extent to which they encrypt data at rest and in transit, and whether they provide products and services where personal data is automatically deleted or expires.

And the protection of privacy is no longer the concern of just technology companies. The shift to a fundamentally digital economy means that, regardless of the sector you are in, your ability to protect individuals will distinguish your company from competitors who have taken a passive approach or who ignore their responsibilities.

Healthcare is an obvious example. Today’s regulatory environment increasingly encourages electronic medical records to improve service quality, increase efficiencies and reduce costs. In the not- too-distant future, some healthcare provider will surely earn a reputation among consumers and within the industry as the company that takes the greatest care to protect their patients’ information. We will likely see similar scenarios in other sectors, such as protecting the driver’s personal data in the age of the connected car and ensuring privacy for students in a digital education system.

New privacy products and services. We are already seeing new products and services from startups and established companies alike that are born from the public’s desire for privacy protections. As we move rapidly into the Internet of Things age – in which connectivity and intelligence are woven into the world around us – individuals will need products to manage their online reputations and protect their identities.

New applications for smart phones and other connected devices will allow individuals more choice over who learns what about them, and what information about them is shared with the connected environment around them. A whole new revenue stream could be generated by giving individuals the ability to keep certain details to themselves. Sure, Dunkin Donuts can offer a free donut when I’m about to drive by, but I would like to control who gets access to that information coming from my phone and how that data is used.

Other companies may focus on providing purpose-driven identification. A jazz club may restrict attendance to only those over 21 years of age, but they do not need to know my name and address to let me in the door.

Behind the scenes, new products and services will target back-end data operations, securing data at its source to prevent a breach long before a customer can be affected.

Winning with privacy. Not unlike the failure of “green washing” that has taken hold related to environmental issues, those who want only to profit off privacy and security issues without providing value will lose. They will be the exception and they won’t last long.

But the businesses who use data in responsible ways to create new solutions and business models – those who place the needs and the protection of their customers and society first – also understand that long-term success will depend on their ability to earn the confidence of their customers.

For example, a GPS application in your car could collect and provide powerful information for you and everyone else driving by, delivering real-time traffic travel route recommendations during commute hours. But a driver may be less enthusiastic to know the application is also sharing driving habits with their insurance company, which could adjust rates based on that information. The business that applies the right formula of risk and reward will win.

For decades, great customer service has been about delighting your customers with friendly staff and business policies. In this digital global economy, the game has changed.

April 17, 2014

Best of the IdeaCast

Featuring Jeff Bezos, Howard Schultz, Francis Ford Coppola, Maya Angelou, Nancy Koehn, Rob Goffee, Gareth Jones, Cathy Davidson, and Mark Blyth.

How to Have an Honest Data-Driven Debate

Malcolm Gladwell of bestselling Tipping Point and Outliers fame proposed a delightfully provocative way to begin his onstage debate with Sports Gene author David Epstein about whether practice or genetics is the better guarantor of professional success. But instead of launching directly into argument, said Gladwell, they’d start by summarizing their opponent’s best arguments. The exceedingly careful, precise and thoughtful characterizations of each other’s position that followed proved remarkably entertaining and informative. More importantly, it facilitated one of the best-reviewed and most absorbing panels at MIT Sloan’s highly-regarded Sports Analytics Conference.

Gladwell’s gimmick of forcing people to fairly communicate their rival’s case is rhetorical old hat. But the rise of Big Data and analytics concomitantly demand its operational resurrection and revival. The need is urgent and global. If there’s a single pathological behavior I consistently see undermining the real and potential value of data and analytics, it’s the rampant intellectual dishonestly and argument I hear in project reviews and board rooms worldwide. Deliberate misrepresentations, mischaracterizations and ad absurdum distortions of fact and interpretation are more common than rare. Passion and commitment are “go-to” executive excuses for grotesque exaggeration and dishonest summary of inter-organizational opposition. Powerpoint presentations become poisonous invitations to quantitative brawls. The dominant metric of analytic effectiveness is “winning the argument” rather than creating any kind of meaningful or measurable insight. Does this represent a serious failure of leadership? You bet. But that’s numeracy’s new normal. It’s why Gladwell’s gimmick so successfully stimulated the MIT sports crowd of geeks, nerds and quants.

The cure is simple and compelling: Managers and executives confronting serious strategic, operational or cultural disagreements on issues that matter should insist that their people be able to convincingly make their opponents’ case. This is not a joke, a gimmick or an intellectual exercise. It’s a public declaration of integrity: Fairly presenting a 360-degree view — both sides of a polarizing argument or wedge issue — is essential to honest and honorable discussion. The best and only way you can be confident your evidence and arguments are understood is by hearing them fairly and accurately made by the very people who disagree with them. That doesn’t mean that they’re persuaded or convinced by them. But it typically guarantees that there’s been a serious investment made in grasping them. Conversely, the best and surest way to demonstrate your own command of the debate is by offering a synthesis and summary of your rival’s case in a manner that leaves them nodding in agreement. There is no shortcut or substitute for that mutual recognition.

I’ve pushed for this in many organizations and unhesitatingly observe that it radically and dramatically elevates the quality of discussion and debate. Intriguingly, the greatest resistance to this comes from managers and executives reflexively dedicated to concepts of authenticity:

“Oh, no!” they piously declare, “It would be dishonest for us—or our colleagues—to have to make an argument we don’t believe in. We won’t do it!” To the contrary, they insist, their passion and dedication are every bit as important as the facts in evidence as to why their position deserves to win. You will not be surprised to learn that these tend to be organizations where politics and power play bigger roles than either analytic rigor or data-driven insight in determining what decisions get made. Confirmation Bias uber alles.

Dan Ariely, the Duke behavioral economist who authored Predictably Irrational, recently addressed this in his Wall Street Journal letters column in a radically different context: “A large body of research on cognitive dissonance has shown that people who are forced to argue for an opinion opposite to their actual one feel so uncomfortable with the conflict that they’re likely to change their original opinion.” I can’t and won’t say that research is consistent with my own empirically anecdotal experience — although I emphatically agree that the overwhelming majority of managers and analysts I’ve worked with are, indeed, uncomfortable arguing against their declared beliefs. I’ve rarely witnessed such contrarian conversions. That said, however, I have seen greater reluctance to characterize enterprise rivals as “morons,” “idiots who don’t know what they’re talking about” and “jerks who don’t really understand the business.” The discipline of being forced to argue the other side doesn’t necessarily create empathy or sympathy but it does — more often than not — create recognition that there are real reasons for disagreement. My experiences suggest that these recognitions lead to greater mutual respect and healthier outcomes than fratricidal debates where dismissing and/or demonizing rivals is culturally accepted and encouraged.

If your organization is having an important argument that gets everybody hot and bothered, don’t encourage compromise or collaboration. Insist that the most passionate and articulate advocates from each side make the other’s case. Force the best and the brightest to publicly demonstrate just how well they understand the other. You — and they — will be amazed at what you’ll learn. If they can’t — or won’t — do it, you’ll be amazed at how irrelevant even the best data and analytics ultimately prove to be.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

The Quick and Dirty on Data Visualization

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious

How to Tell a Story with Data

Help Your Employees Find Flow

Holacracy. Results-Only Work Environments. These new, more flexible ways of working may be a step too far for many organizations. Still, greater employee freedom can create a better sense of “flow,” which enhances engagement, retention, and performance. This can be achieved by loosening your grip on work practices — but you don’t have to let go completely: remove obstacles, set boundaries and meaningful goals, then let work take its course.

Stefan Groschupf, founder and CEO of Datameer, a big data analytics company, talked with me about how he tries to reduce negative interruptions and increase “flow.” His industry is one of the most pressured to recruit and retain top talent. He’s finding that the organization is more productive (e.g., has more leads generated in marketing or has engineers moving through projects more quickly) with active management of interruptions and engagement to enhance flow.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author of the landmark Finding Flow, describes the feeling of flow this way:

Imagine that you are skiing down a slope and your full attention is focused on the movements of your body, the position of the skis, the air whistling past your face, and the snow-shrouded trees running by. There is no room in your awareness for conflicts or contradictions; you know that a distracting thought or emotion might get you buried face down in the snow. The run is so perfect that you want it to last forever.

Flow has been tied to performance by improving concentration and motivation. But when you’re constantly interrupted, it’s hard to find a state of flow. One workplace study found an average of almost 87 interruptions per day (an average of 22 external interruptions and 65 triggered by the person himself). Then, on average, it takes over 23 minutes to get back on task after an interruption, but 18% percent of the time the interrupted task isn’t revisited that day. For some, interruptions “form the genesis of the work,” so it’s hard to say that all interruptions are bad — but work design and management needs to offer the opportunity and knowledge to manage interruptions.

Groschupf’s techniques for combating interruptions and fostering flow are straightforward: allowing people to switch off email, fewer meetings, and focusing on smaller chunks of work. These strategies, however, wouldn’t be as effective if just one person made these changes to his or her individual work. The key is that the whole organization is on board. Groschupf says that they have clear organizational goals — and that all employees know engagement and flow are important to reach those goals.

And yet the CEO is skeptical of the hype around gamification — the latest engagement fad. “What’s behind gamification? It’s flow.” He believes that if management can create an environment where employees love the experience and feel fulfilled in their jobs, then engagement, retention, and performance will follow.

He’s learned that turnover is usually not about the money. “It’s about achievement.” Games and flow are characterized by relatively short challenge-and-reward cycles. This approach is similar to the recommendations in Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer’s recent book, The Progress Principle, where they demonstrate that even small wins fuel motivation. Groschupf works to build those powerful little wins into the business. He’s not controlling the work, but he is setting the rules for making the work more engaging.

As a data-driven business, Datameer is always tracking results, so people can see their progress and how it fits into the rest of the organization’s work. Groschupf notes that it’s helpful being a young company – Datameer has been able to build measurable processes as it goes. He acknowledges that it would be harder to add these tools on to legacy systems. But I’ll offer that practices enabled with collaborative goal-setting tools like Work.com are one way to add some of this capability to an existing system.

The approach at Datameer is not just tool-and-metric-based. There is also a human dimension to their practice. Groschupf says, “It’s a learning process. You can’t just go to someone and say that the way we run this company is data driven. There is a human element. As you get new folks that might not be knowledgeable, it’s important to socialize them and help them understand.”

Loosen your grip on tactics like meetings and email, and focus on reducing interruptions and increasing engagement. Create shorter and more visible challenge-and-reward cycles and let employees go with the flow.

The Secret Ingredient in GE’s Talent-Review System

GE is often highlighted as an organization that develops some of the most effective leaders. Most companies have a version of the talent-review system we use at GE. But judging from what I hear from managers of companies that visit us to benchmark our system, the difference between our approach and theirs does not lie in forms, rankings, tools, or technologies. It lies in the intensity of the discussion about performance and values. The debate, the dialogue, and the time taken to have an exhaustive view of an individual − evaluating them based on both what they accomplish and how they lead − are far more important than any of the mechanics. The heart of our system has always been about the enormous time commitment the organization and the leadership devote to the conversation about people.

As the custodian of the talent-review process, I have been lucky to observe this at close quarters. Here is what I’ve learned.

It starts with the attention given to the individual appraisal. Managers are expected to dedicate time to prepare for a detailed discussion of a direct report’s performance and values, strengths, development needs, and development plans. Most employees spend over 1,800 hours a year working for the manager and the company. Is it unreasonable to expect the manager to spend at least a few hours thinking about and discussing the performance appraisal as part of a larger commitment to helping the employee be more successful? (More about that in a moment.) Individual appraisals are considered enormous opportunities for the candid, constructive conversations that employees deserve.

It is not uncommon for a manager’s assessment and feedback to be questioned by his or her own manager, if the commentary does not appear to reflect the individual accurately. I have seen our top leaders return an appraisal because it did not do justice to the feedback on the individual. Such a disconnect is the worst thing that can happen because it is a reflection of the manager, or the HR manager, as much as it is of the employee. This practice of multi-level engagement ensures that the quality of the appraisal is honest and comprehensive.

We continue to use a nine-block grid with quadrants that capture levels of performance and values not as a means of a forced ranking but as a way of facilitating differentiation. Here is how it is done. As our businesses and functions go through the process, the leaders justify the positioning of talent in different quadrants of the grid. The system allows us to link the grid straight to the appraisal. The chairman sets the overall tone and expectations, and leaders across the company make suggestions, comments, and additions to the feedback. While each leader may only have visibility into his or her particular business, the system ensures consistency and provides a consistent view and assessment of talent across the company.

Most of our leaders, including the chairman, spend at least 30% of their time on people-related issues. It’s part of our operating rhythm. These discussions are rich in making calls on leadership, succession, opportunities for development, organization and talent strategy, diversity, and global talent builds. The discussions also afford us the opportunity to assess performance more closely and holistically − including market factors, internal factors, organizational complexity, and risk elements. More importantly, it is the business leaders who take the lead on these discussions, not the HR person. This is consistent with our philosophy that talent development and assessment is a key business agenda, not just an HR activity.

Some skills are more important than others to be a great leader. As I have observed these discussions, some of the patterns are becoming increasingly obvious to me. For instance, the difference between a great leader and a good one is not just about intellectual capacity; it is often about judgment and decision-making. Likewise, a hunger to win, tenacity, customer advocacy, and resourcefulness can trump some of the skills we often look for − analytical skills, for instance. Such traits are best unearthed through discussions and become important considerations for future talent mapping.

Effective talent review is an intensely human process that calls for extensive demands on a leadership’s time. There are no formulas or equations. The power lies in giving people the attention, candid feedback and mentoring they deserve through a company-wide commitment to human-capital development.

The Two Questions Every Manager Must Ask

When something seems too good to be true, it usually is. And management techniques, practices, and strategies are no different. When you read a business book or attend a presentation on a particular management practice, it is a good habit to explicitly ask, “What might it not be good for?” When might it not work; what could be its drawbacks? If the presenter’s answer is “there are none,” a healthy dose of skepticism is warranted.

Because that’s unfortunately not how life works, and that’s not how organizations work. It relates to what Michael Porter meant with being “stuck in the middle”: if you try to come up with a strategy that does everything for everyone, you will likely end up achieving nothing. If you focus your strategy on, for instance, achieving low costs, you will likely have to sacrifice delivering superior value on other dimensions, and vice versa.

Similarly, “doing well by doing good” – enhancing your firm’s financial performance by achieving superior corporate social responsibility – is often easier said than done. When confronted with an ethical decision – e.g. whether to dump toxic waste in a developing country, where it may not be illegal, when all your competitors do so as well – it sometimes costs you (a lot of) money to do the right thing. Dozens of academic studies have tried to establish a positive link between corporate social performance and profitability, but for every study that finds a (modest) positive correlation, there is one that doesn’t.

But it seems some organizations do pull it off.

Take the company Aravind Eye Care in India. It was founded in 1976 specifically to provide cataract eye surgery. They modeled their operations on McDonalds: high volume, highly efficient operations, based on division of labor and cost efficiency. It is a very profitable operation; the company has a gross margin of 50 percent. Yet, the remarkable thing is that they treat 70 percent of their customers for free. The 30 percent that do pay are relatively affluent people who can afford the operation, but who receive pretty much the same service. In fact, the company goes out of its way to actively recruit non-paying customers. It goes to look for them systematically in the countryside and transports them to their clinics for free.

This, while the clinical quality of their service – the cataract operation – is second to none. Similarly, other medical clinics are operating in India – for instance in heart surgery – that combine extremely efficient, low-cost operations, but at very high quality in terms of clinical outcome. To such an extent that various National Health Service hospitals in the United Kingdom are considering sending their patients to India; to save money, while providing them with superior quality treatment.

How can these organizations combine higher quality with lower costs? How can they combine doing well by doing good, and treat 70 percent of patients for free at 50 percent gross margins? The trick is that their business models are built for the long-term. Paradoxically, in the long-run, the lower costs enable them to provide better quality.

Ask yourself this: Could Aravind Eye Care make more money if it did not treat the 70 percent non-paying patients? Although it may seem that this would save them a lot of costs, in fact, the answer is very likely “no”. Every organization learns with experience. We call this effect “the learning curve”. With experience, firms increase the efficiency and quality of their production. These curves have been documented for airplanes, cars, bottles, pizzas, and so on. And cataract eye surgery is no exception.

It is because these clinics treat such very large number of patients, the company runs down its learning curve very quickly, giving it a substantial competitive advantage. Moreover, the vast number of patients enables it to divide labor to the extreme, creating specialist roles and highly-experienced people in all parts of the procedure. The 70 percent non-paying customers form the basis of this advantage. Consequently, the company would likely not be able to attract the 30 percent paying customers without them.

It is often said that Aravind’s paying customers subsidize the 70 percent that get the operation for free, yet, in many ways, it is the other way around: Treating the vast numbers of non-paying patients enables the company to deliver the quality that attracts the ones that do pay.

What enables companies such as Aravind to combine all of these things? Didn’t I say at the beginning of this piece that “when something seems too good to be true, it usually is?” and that “it is always a good habit to explicitly ask what might it not be good for?” Yes, but that is because there is a second question you should always ask, when considering a particular management technique, practice, or strategy, and that is: “What might its long-term effects be?”

What might seem a good idea in the short-run does not always work in the long term – and vice versa. Unfortunately, most companies make decisions based on their short-term consequences, because that is what they can see and measure. If, like Aravind, you optimize your business model for the long haul, you might be able to deliver superior quality at lower costs. And even do some good for society in the process.

Easing the Load of the Battery-Powered Soldier

Batteries account for about 30 of the 90 pounds of gear carried by U.S. soldiers and Marines, Navy official Roger M. Natsuhara tells the Wall Street Journal. That’s because a lot of their equipment, from infrared viewers to communicators, is powered. The military has now developed unrollable photovoltaic panels for recharging batteries, so that fewer batteries are required and, thus, fewer have to be thrown away—an important security issue, because a trail of dead batteries shows the enemy where soldiers have been.

Why the Financial Services Industry Is Showing More Women in Its Ads

Financial services firms want to reach more women; so I conclude from data presented by Pamela Grossman of Getty Images at SXSW this year. According to data collected by Getty, financial firms are buying 20% more stock photos of women today than they were five years ago. At the same time, the share of men shown in their advertising has declined.

Of course, we live in a wildly diverse world; we want to be inclusive and broad minded ourselves; and we therefore want our providers of financial advice, energy, and technology to reflect those values. We prefer Morgan Stanley or CitiGroup to be talking to all of us, showing us that they have transcended their traditional, mostly white and male clientele. According to Chris Edwards, former Group Creative Director for Arnold Worldwide, we also want visual evidence that the professionals at these firms are as diverse as the clientele they seek. Advertising images reinforce and extend these efforts.

Financial institutions portray women today as competent and self-confident, and often feature attractive, middle-aged advisors talking to couples in which the woman is similarly well dressed and clearly attentive. According to Dr. Emma Firestone, who has studied the audience perception and response to images and words in media and entertainment, from a cognitive perspective, “It makes sense for advertisers to present women as strong, well-educated consumers. This is appealing to women who see an attractive self-image reflected back at them, and to men, who are flattered by the idea that smart, self-possessed, and financially secure women are their own life partners.” Men are much more likely today, than decades ago, to be comfortable with and appreciate their spouses as full partners in their own financial decision-making – at the same time, imagery of supportive female financial advisors plays into comforting stereotypes of the woman-as-helpmeet, perhaps humanizing an industry consumers view as confusing or even threatening.

However, there is a trapdoor in this picture. The rise in strong feminine images in financial advertising also coincides with some very negative portrayals of men in the industry: the testosterone-driven traders and gamblers who led us over the financial cliff in 2008. As Christine Lagarde, Director of the International Monetary Fund has famously stated, only partly in jest, if the firm had been called “Lehman Sisters” there might not have been the same resulting devastation to world economies. There has been extensive coverage of research suggesting that if financial firms had fewer men, those firms would have taken on less risk. Both headlines and Hollywood have also focused on the antics of a few particularly macho financial executives, from the “Wolf of Wall Street” to the “London Whale.” It may be that today’s financial firms are trying to portray a “feminized” face to distance themselves from stereotypes like these.

But it’s not all “optics” – more and more women are actually taking on breadwinning roles. Grossman touched on several demographic factors supporting the trend: one-third of working women earn more than their husbands, 40% of households with children under 18 are headed by a women; and female students account for 57% of undergraduates in the United States. More women have also taken on more responsibility for retirement planning, in part due to market and retirement plan upheaval; in 1978, the IRS created the structure in which the federal government essentially shifted the burden of retirement financing from employers to employees. Without the safety of defined benefit pension plans in a era of diminished job security, most Americans, as couples or individually, need to be much more active players in the dialogue about their own asset allocation and investment options well in advance of retirement.

Mark McKenna, Head of Global Marketing at Putnam Investments, says he’s also seen women assuming prominent roles in the personal finance sector; whether they have been stay-at-home moms or asset builders in their own names, women often have primary control of the finances and they generally outlive their spouses. The statistics are staggering: Baby Boomer women control over 60% of the country’s wealth; women make 80% of the US collective household buying decisions; 41% of the 3.3 million Americans with incomes over $500,000 a year are women; and they account for over 50% of all stock ownership. The financial services industry needs to reflect these realities and speak directly to women.

Of course, it’s not enough to show women in their advertisements; the next step is for financial services firms to effectively engage women with products and services tailored to their needs and desires, including a risk profile that’s distinct from men’s. While men are more interested in wealth accumulation, according to a large-scale study by BCG, women focus on long-term financial security for themselves and their families. They value being heard and respected by their financial advisors and place trust as a very high priority. Offering more images of women in advertisements is a clever marketing step to improve sales; serving these clients well is the key to building that business over the long term.

April 16, 2014

The Quick and Dirty on Data Visualization

Displaying data can be a tricky proposition, because different rules apply in different contexts. A sales director presenting financial projections to a group of field reps wouldn’t visualize her data the same way that a design consultant would in a written proposal to a potential client.

So how do you make the right choices for your situation? Before displaying your data, ask yourself these five questions:

1. Am I presenting or circulating my data?

Context plays a huge role in how best to render data. When delivering a presentation, show the conclusions you’ve drawn, not all the details that led you to those conclusions. Because your slides will be up for only a few seconds, your audience will need to process them quickly. People won’t have time to chew on a lot of complex information, and they’re not likely to run up to the wall for a closer look at the numbers. So, think in broad strokes when you’re putting your charts together: What’s the overall trend you’re highlighting? What’s the most striking comparison you’re making? Those are the sorts of questions to answer with projected data.

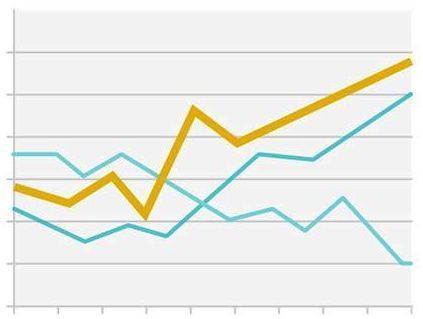

Scales, grid lines, tick marks, and such should provide context, but without competing with the data. Use a light neutral color, such as gray, for these elements so they’ll recede to the background, and plot your data in a slightly stronger neutral color, such as blue or green. Then use a bright color to emphasize the point you’re making, as in this example:

It’s fine to display more detail in documents or in decks that you e-mail rather than present. Readers can study them at their own pace — examine the axes, the legends, the layers — and draw their own conclusions from your body of work. Still, you don’t want to overwhelm them, especially since they won’t have you there in person to explain what your main points are. Use white space, section heads, and a clear hierarchy of visual elements to help your readers navigate dense content and guide them to key pieces of data.

2. Am I using the right kind of chart or table?

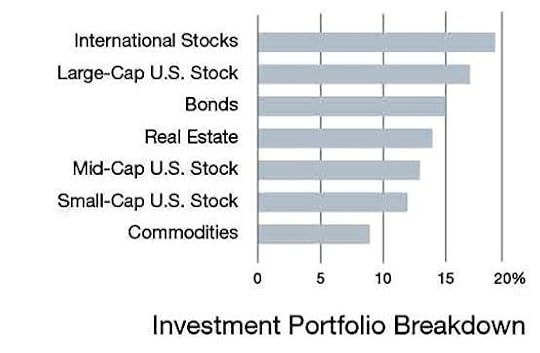

When you choose how to visualize your data, you’re deciding what type of relationship you want to emphasize. Take a look at this chart, which shows the breakdown of an investment portfolio:

In the pie, it’s clear that this person holds a number of investments in different areas — but that’s about all you see.

Here are the same data in a bar chart:

Now it’s much easier to discern how much is invested in each category. If your focus is on comparing categories, the bar chart is the better choice. A pie chart would be more useful if you were trying to make the point that a single investment made up a significant portion of the portfolio.

3. What message am I trying to convey?

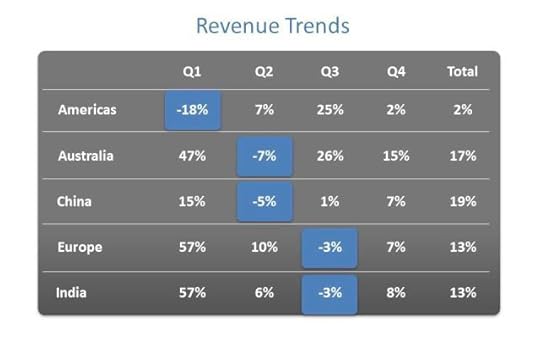

Whether you’re presenting or circulating your charts, you need to highlight the most important items to ensure that your audience can follow your train of thought and focus on the right elements. For example, this chart is difficult to interpret because all the information is displayed with equal visual value:

Are we comparing regions? Quarters? Positive versus negative numbers? It’s difficult to determine what matters most. By adding color, you can draw the eye to specific areas:

We now know that we should be focusing on when and in which regions revenue dropped.

4. Do my visuals accurately reflect the numbers?

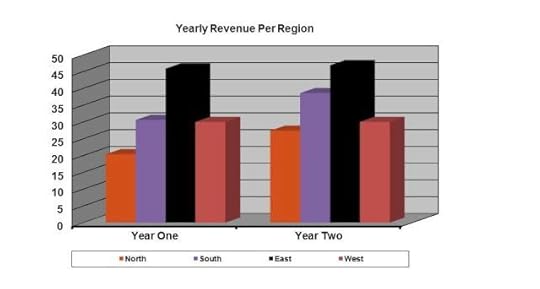

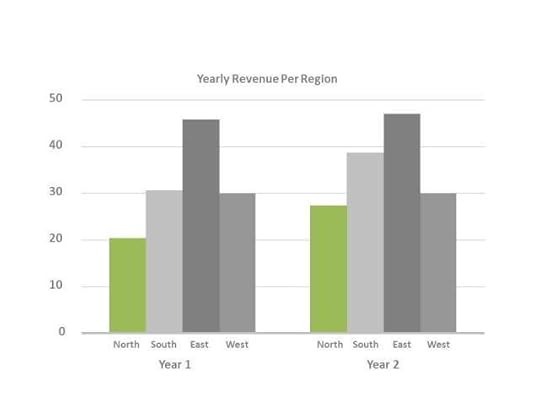

Using a lot of crazy colors, extra labels, and fancy effects won’t captivate an audience. That kind of visual clutter dilutes the information and can even misrepresent it. Consider this chart:

Can you figure out the northern territory’s revenue for year one? Is it 17? Or maybe 19? The way some programs create 3D charts would lead any rational person to think that the bar in question is well below 20. However, the data behind the chart actually says that bar represents 20.4 units. You can see that if you look at the chart in a very specific way, but it’s difficult to tell which way that should be — even with plenty of time to scrutinize it.

It’s much clearer if you simply flatten the chart:

5. Are my data memorable?

Even if you’ve rendered your data clearly and accurately, it’s another challenge altogether to make the information stick. Consider using a meaningful visual metaphor to illustrate the scale of your numbers and cement the data in the minds of your audience members. A metaphor can also tie your insights to something that your audience already knows and cares about.

Author and activist Michael Pollan showed how much crude oil goes into making a McDonald’s Big Mac through a striking visual demonstration: He placed glasses on a table and filled them with oil to represent the amount of oil consumed during each stage of the Big Mac production process. At the end, he took a taste of the oil to drive home his point. (To add an element of humor, he later revealed his prop “oil” to be chocolate syrup.) Watch the video here:

Pollan could have shown a chart, but this was more effective because he gave the audience a tangible visual — one that triggered a visceral response.

By answering these five questions as you’re laying out your data, you’ll visualize it in a way that helps people understand and engage with each point in your presentation, document, or deck. As a result, your audience will be more likely to adopt your overall message.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious

How to Tell a Story with Data

To Go from Big Data to Big Insight, Start with a Visual

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers