Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1434

April 25, 2014

Why Corporate Social Responsibility Doesn’t Work

Christine Bader, whose job at BP was to "assess and mitigate the social and human rights risks to communities living near major BP projects," was not able to help prevent the Deepwater Horizon disaster or the 2005 BP refinery explosion in Texas City. This despite doing important work for a company that seemed committed to social responsibility. In her quest to figure out why good corporate intentions don't prevent tragedies, Bader uncovered six themes that get in the way of making progress. Among them: People lie. No one gets rewarded for disasters averted. Customers won't pay more. And no one really knows what corporate responsibility actually is. Bader points out that we all have a role to play in making things better: The general public must "recognize the real costs of safety and sustainability," and companies have to "bear witness to their impacts, improve internal communication, reduce incentives to lie, and reward prevention.”

Hell Is a Start-UpNo ExitWired

Guess what? Running a start-up isn't the booze-soaked, foosball-fueled Silicon Valley dreamscape some would have you imagine. This measured, deeply reported piece by Gideon Lewis-Kraus tracks two entrepreneurs (disclosure: I went to high school with one of them) as they work feverishly to save their young company. Or, to put it more bluntly, "They had a month to raise $1 million or they would no longer be able to make payroll." Lewis-Kraus is with these founders as they attempt to make this happen. He also spends time in a hacker house with fresh SV recruits; he paid "$1,250 for a mattress on the floor, behind a panel of imbricated torn shower curtains, in an unheated rabbit warren of 20 bunk beds under a low converted-warehouse ceiling." It's an important look into what it's really like to try and "kill it" in a world that "is not a place where one is invited to show frailty or despondence."

The Mating DanceRisk and the Unmarried CEO Knowledge@Wharton

Why, exactly, is the CEO of your company embarking on that daring capital expenditure that's got analysts shaking their heads? Is it all about a unique vision of the company's potential? Or something more personal? If the chief executive is unmarried, maybe he (or she) is just trying to attract a mate. Nikolai Roussanov of Wharton and Pavel G. Savor of Temple found that firms led by single CEOs engage in much more aggressive investment behavior, in terms of capex, innovation activity, R&D, and acquisitions, than companies led by married chief executives. The potential for an increase in personal wealth may be a factor – "single individuals are clearly competing for potential mates with other single individuals," and socioeconomic status is a major attractor. It's also possible that single CEOs are generally less risk averse because they don’t have families to worry about. The same kinds of dynamics probably play out among lower-level managers too, Roussanov says in this Wharton video. –Andy O'Connell

The Productivity Police The Secret History of Life-Hacking Pacific Standard

Ever wonder why "life hacking" is such a thing, why people get so excited about little ideas for how to be happier and more productive at work? Ideas such as tracking your sleep habits with motion-sensing apps and calculating your perfect personal bedtime? Nikil Saval writes on Pacific Standard that life hacking's popularity says something about How We Live Today – it wouldn’t be popular if it didn’t "tap into something deeply corroded about the way work has, without much resistance, managed to invade every corner of our lives." What life hackers don’t realize, he says, is that there's something dehumanizing about life hacking itself. It turns every aspect of daily existence into a task to be managed: "Rather than putting people in greater control of their lives, it puts them into the service of a stratum of faceless managers, in the form of apps, self-administered charts tracking the minutiae of eating habits and sleep cycles, and the books and buzzwords of gurus." What we've really done is internalize Frederick Winslow Taylor's century-old concept of scientific management for factory workers. We have become our own productivity police. –Andy O'Connell

Buy Me Some Peanuts and Very Few SuperstarsJohn Henry and the Making of a Red Sox Baseball DynastyBusinessweek

I would be remiss if I didn’t include this feature by Joshua Green on HBR's hometown heroes. Yet the things that made the Red Sox so memorable on their path to World Series victory – "their team chemistry, their beards, and the emotional bond they forged with the city in the wake of the marathon bombing" – were in fact the last things on owner John Henry's mind when orchestrating the team. "It was the ability to ignore sentiment that paved the way for their success," Green writes. He explores Henry's methodical and mathematical talent strategy, which relies on impermanence (few long-term contracts for team veterans); young, cheap talent ("it's not expensive players, but inexpensive ones, who are becoming baseball's prized commodity"); and players who can just plain get on base. If you're game for a read that combines all of this, plus commodities futures trading and the phrase "he looked like the Angel of Death," look no further.

BONUS BITSHappy Birthday?

Twenty Years of Spam (Cloudmark)

The First Unit Is Expensive: Wu-Tang Clan Edition (Digitopoly)

The Biggest Contributor to Brand Growth (Bain Insights)

A Tool That Maps Out Cultural Differences

Understanding cultural differences isn’t easy, even when you’ve lived in many different countries (disclosure: I’m a Brit, grew up in Southeast Asia, lived and worked in Switzerland and the US, and now live and work in France). Just when you think you’ve got a culture nailed, something happens that your mental model hasn’t predicted.

Americans, world-famous for candor and directness, struggle when it comes to giving tough feedback, even when it’s needed. The French, on the other hand, who are famous for their insistence on good manners (just feel the vibe when you forget to say bonjour to your boulanger), revel in their harsh critiques. Paradoxes like this crop up all the time, and obviously they’re a good source of anecdotes. But in a business world that increasingly relies on culturally mixed workforces and teams, they’re also recipes for failure.

Erin Meyer, an American (from Minnesota) in Paris who coaches executives in managing cross-cultural career moves and teaches at INSEAD in Fontainebleau, has a theory about these malentendus. The problem, she argues, is that most people tend to emphasize just one or two, at most three, dimensions of cultural difference when it comes to parsing and predicting foreigners’ behavior.

But cultures differ along many more than three dimensions, so the more dimensions you consider, the less likely you are to trip up on a cultural paradox — you’ll be able to tell that incoming French manager to tone down critiques of his American subordinates before he upsets them.

The trouble, of course, is that it’s cognitively difficult for us to keep more than three dimensions of comparison in our head at once. What’s more, we tend to lose sight of the fact that relative, not absolute differences, are what matters. Most cultures would find the Brazilians to be very relaxed about punctuality, for instance, but Brazilians themselves tend to struggle to adapt to Indians’ even more casual notions of time.

So Meyer developed a tool to help us better navigate the cultural minefield more systematically. She identified eight dimensions that, in her experience and from research, seem to capture most of the likely differences between cultures, and she rated a large sample of countries on these dimensions. You can see below how certain country pairs differ along these eight dimensions — and where the problems with each pair are most likely to occur and what you might do to mitigate them.

View a larger version of the interactive here.

Marketers Need to Think More Like Publishers

In 2010, Pepsi pulled its Super Bowl ads and invested $20 million into its Refresh project, which employed crowdsourcing to support good causes. It was an astounding social media success, with more than 87 million votes cast.

Unfortunately, as this Harvard Business School case study points out, it was an abysmal business failure and Pepsi eventually fell to third place in the soda category, behind Diet Coke. For all of the hype and hoopla on social media, sales suffered dearly.

Pepsi’s ambitions were far from unusual. Research by the Content Marketing Institute estimates that 90% of consumer marketers are investing in content. Unfortunately, most of those efforts will fail. In order to succeed, marketers will have to learn to think like publishers. That will mean more than a change in tactics or even strategy, but a starkly different perspective. Here’s what you need to do:

1. Define the mission. All great publications have missions. Helen Gurley Brown sought to make every girl feel that she can be beautiful and confident. That’s Cosmopolitan’s mission. Henry Luce sought to create a better-informed public and Time magazine embodies his vision even today. Vogue is a fashion bible because Anna Wintour believes a stylish world is a better place.

Marketers need to take the same approach. Nobody is going to believe that the CEO of Pepsi wakes up in the morning thinking about how she can build better after-school programs and bike trails, which is why Pepsi Refresh didn’t resonate. Others, like American Express Open Forum succeed because they are in line with the brand’s mission.

Coke has taken an interesting approach with its sustainability initiative. Water quality and energy efficiency are important to Coke’s business and it has built up considerable expertise in that area. People who have an interest in the issue appreciate the company sharing it and if they can get an occasional coupon in the process, so much the better.

Most content marketers start with implementation ideas, such as social media or a video. That would be like John F. Kennedy proposing his man-to-the-moon idea by focusing on rocket technology, rather than America’s aspirations for the space age.

Start by figuring out what you have to offer the world. Most companies usually actually do have quite a bit to offer, but get bogged down because they haven’t identified their mission.

2. Identify analogues. Marketers like to cut through the clutter and get noticed. They focus on “unique selling propositions” and want their marketing messages to be distinctive. By looking, sounding, and feeling different, they hope to grab the consumer’s attention.

But marketing in the digital age is less about grabbing attention and more about holding attention. That goes double for publishing. You need to create an easy-to-navigate experience that will make consumers want to come back. The best way to do that is by adopting familiar conventions.

That’s why content development should always start with between three and five analogue products. You need to ask key questions like: Who’s done this before? How did they do it? What can we add? What can we subtract? For example, if a cosmetics brand wanted to publish content, would their reference be Cosmo, a Sephora store, or Sex and the City?

Starting with analogues is the best way to get everybody on the same page and define what you want to achieve. From there, you can find your own voice.

3. Identify your structures. Possibly the most important — and certainly the most overlooked aspect of content creation — is structure. Every content discipline has its own rules and every content product is defined by the rules it chooses to break.

Magazines have clearly defined “brand bibles” that designate flatplan, voice, and pacing. Radio stations run on clocks. TV shows have clearly defined story structures and character arcs. The rules not only set audience expectations and make content easier to take in and enjoy, but form the crucial constraints in which creativity can thrive.

So when marketers approach publishing, they must go beyond the usual advertising conventions of target and message. Instead, they must think seriously about the format in which information will be presented. You may not need the detailed brand bible of an established publication — which can run up to 100 pages — but you have to start somewhere.

Every great publishing product combines consistency and surprise, so it’s okay to break some rules now and again, but you have to first establish what the rules are.

4. Create a true value exchange. It used to be that awareness could drive sales. If you spent lots of money on TV, you could be sure that consumers would know your brand and be more likely to buy your product. But today, brand awareness is less likely to result in a trip to the store and more likely to lead to searching behavior online, where your competitors can retarget your consumers.

That’s why it has become so important to build a relationship with consumers. Publishing can be a great way to build unique bonds, but there has to be a true value exchange rather than just a promotion. Gimmicks won’t work. You need to build trust and credibility through content that makes an impact because it informs, excites, and inspires. The Michelin Guides, which started out as basic handbooks for road-weary travelers (presumably traveling on their Michelin tires) are the classic example. A more modern example is Mailchimp, the email marketing service, which sends tutorials on how to get the most out of its product after you sign up.

Most of all, great publishers lead. People like Helen Gurley Brown, Henry Luce, and Anna Wintour created legendary brands by driving trends, not following them. They do not seek to merely join the conversation, but to lead it. If you expect people to listen to you, it’s best to have something meaningful to say.

If marketers are ever going to be successful at content, the first step is to start thinking more like publishers.

Midsized Companies Can’t Afford Operational Glitches

Many midsized companies dream of joining the Fortune 500 someday or of becoming the next General Electric, Microsoft, or Amazon. But they don’t think nearly enough about operational meltdowns – technological glitches and other problems that can put them out of business. As a result, most are singularly unprepared to deal with them.

This lack of adaptability is not a problem in most small companies. They are usually quick to recognize operational problems and deal with them before they become disasters. If they don’t, they could go out of business overnight. Take Instagram, the San Francisco-based social media company. In October 2010, when its founders launched their website to the world, 25,000 web viewers overwhelmed the site. Instagram’s founders called their Stanford University friends, and the entire group worked 24 hours around the clock to keep the servers from crashing, transferring their traffic to Amazon’s servers. A month later, the site could handle a million simultaneous users. Instagram dodged an operational meltdown that could have rendered the start-up dead on arrival.

Operational meltdowns at midsized companies can take much longer to notice and resolve. Firms in this segment have many more “moving parts” than start-up companies – systems connected to other systems, more layers of management through which bad news in the field must travel, etc. Unlike much larger companies, midsized firms usually lack deep operational and technological talent who can quickly recognize, understand, and resolve huge systems glitches. All these factors underline the point: Midsized companies are often the most likely to be brought down by operational meltdowns.

From my research, consulting experience, and more than 20 years as CEO of a midsized firm (in the decorative art publishing industry), I have found four signs that signal when an operational meltdown is probable in a midsized company:

An overbearing sales culture. In midsized companies, no order is ever too unreasonable to fulfill. But this creates havoc for their production and distribution functions. They don’t have the budgets of Fortune 500 companies, which can customize products and delivery for each customer who requests special treatment. Here’s what happened at a midsized company that was founded and led by a salesman. As his firm grew, he undervalued and underpaid the executives who ran the supply chain and finance departments. That, of course, meant he did not have highly competent executives running these functions. That led to a high number of errant shipments and to customers not paying their invoices according to the terms of payment, often because they weren’t getting the correct shipments on time. Meanwhile, his cherished salespeople said yes to just about every customer demand (following the CEO’s credo), which exacerbated the erroneous shipments problem. Customers delayed payment for months, which eventually helped force the firm into bankruptcy. To counterbalance an overbearing sales culture, midsized firms need an executive who loves operations, heart and soul, and hates risk and sloppiness. The CEO must shift the culture toward one that prizes execution just as much as sales.

An outdated IT or physical infrastructure. Midsized companies are often starved for capital to renew their infrastructure. Capital investments typically focus on items that move the top line: R&D funding, sales force automation systems, and the like. Certainly, operational and IT infrastructure spending does drain the bottom line, but if a midsized firm doesn’t make the right investments when they are necessary, the top line eventually erodes. The best midsized companies avoid this by shifting their annual budgeting cycle to quarterly or semiannually. The shorter time frame forces functional heads to predict their short-term needs and gives them a better chance of filling them. Equally important, such companies gently deny customer requests to which their operations can’t respond. Dave’s Killer Bread is a case in point. As a $3 million baker in Milwaukie, OR, the firm had already outgrown the capacity of its 15,000-square-foot bakery by 2006. Then Costco came knocking on Dave’s doors to supply its warehouse clubs, but Dave’s had to turn the giant retailer down. It couldn’t handle Costco’s demand without a huge investment in a new bakery. Later that year, Dave’s got $2.1 million in financing for a new 50,000-square-foot bakery, which opened in 2008. After waiting patiently, Costco became a customer, and by 2011, Dave’s sales rocketed to $50 million.

A shortage of key skills. The inability to find, develop, and keep key people during periods of rapid growth triggers many an operational breakdown. The skills that midsized companies need today – which weren’t necessary when they began life – expand rapidly, requiring subject matter experts in niches that small firms don’t need and big firms already have in place. Imagine a firm with 120 people at the beginning of the year that needs to design positions, hire, and onboard 80 new people in one year. Most firms with 120 people don’t have much of an HR function in place. Bringing in many people with critical new skills is too difficult to manage for the average functional head in a midsized company. The best midsized companies delegate recruitment and training to the HR function (which may need to be built up), which allows functional heads to focus on their daily activities.

An overreliance on a few big customers. The CEOs of midsized firms are often reluctant to commit major funding to any operational or IT infrastructure item that isn’t immediately necessary to keep their key customers’ business. But if accounting, manufacturing, and distribution systems are woefully inadequate, the shortcomings catch up to the company at some point – particularly if it lands one more big customer. Although it feels risky (and it is), building operations infrastructure can be a key differentiator. Midsized firms often lack up-to-date infrastructure and small firms usually don’t have it. It increases the likelihood of keeping big customers and qualifying for many more of them. Ultimately, the best way to reduce customer concentration is to get several other large customers.

Midsized companies which successfully avoid operational meltdowns make it their practice to divert money and attention away from activities focused on the top line (especially sales and marketing) and toward operations that deliver on the promises made to existing customers: production, distribution, customer service, and IT. Such companies as Dave’s Killer Bread resist the urge to say “yes” to new business that will severely tax the existing infrastructure, no matter how big the top-line potential.

How Mental Biases Distort Perceptions of MBA Program Rankings

When considering MBA programs and colleges that move up in published rankings, people are most impressed when the movement crosses a round-number category, such as from number 11 to number 10, as opposed to moving from 10 to 9, say Mathew S. Isaac of Seattle University and Robert M. Schindler of Rutgers. This “top ten” effect shows that consumers mentally divide lengthy rankings into smaller sets of categories and exaggerate differences between numbers that cross category boundaries. Organizations that depend on their public rankings would do well to invest aggressively in improving their positions if doing so might push them into a higher round-number category, the research suggests.

4 Ways the Best Sales Teams Beat the Market

Customers today use an average of six channels during the buying process, and the number of channels available to them is only increasing. Competition for those customers has also increased as margins have tightened. Digital channels have upended the well-trod ruts of sales and marketing organizations — already, nearly a third of all B2B purchases are done digitally. All of this increased complexity means sales leaders must rethink how they source leads, manage pipelines, and sell more effectively.

Rather than being overwhelmed, the best sales leaders have figured out how to overcome this complexity to drive above-market growth. Our analysis of 73 B2B technology companies shows that across sectors, the top 25% of companies achieve more than twice as much return on sales investment compared to the bottom 25%.

What do they do right? Based on our experience and analysis, they maintain a clear focus on four things:

1. They measure sales ROI differently. The key to smart investing is having good data that highlights where the greatest sales ROI is. That starts by knowing what to measure. Many companies, however, measure sales efficiency in terms of sales cost versus revenue. That metric is misleading because it does not sufficiently reflect the margin differences between sales channels. A more meaningful sales ROI is to measure sales cost against gross margin or profit (EBIT), which helps leaders more effectively align the number of accounts per sales employee with actual and potential revenues. By analyzing the sales ROI potential of various segments, for example, sales leaders uncover different channel approaches for each. In one company, analysis revealed that sales ROI in indirect channels was 50% greater than in direct channels.

The best leaders also achieve such high sales ROI by reducing overall sales costs without giving away too much margin. Approaches include a strong “quality instead of quantity” focus on their highest-performing partners. They also tend to de-emphasize direct discounts, such as rebates and product offerings.

2. They keep sales costs low. While the old adage “it takes money to make money” is popular, it’s not true when it comes to the best sales leaders. The best of them keep their costs lower than their peers do. Some 72% of companies in the top quartile of sales ROI also have the lowest sales costs. Effectively controlling costs requires a clear and objective view of profitability and cost-to-sell by channel, product, and customer.

With this foundation, sales leaders can make better decisions, such as scaling back sales efforts for lower value orders. They also invest in processes and training that cut costs, such as installing technologies that reduce the number of order exceptions and cross-training people to have multiple skills. This level of efficiency not only reduces costs but also allows sales leaders to profitably pursue lower-margin business.

3. They free up their salespeople for selling. Top performing sales organizations have the same percentage of sales staff in sales management roles — around 8% — as lower-performing companies. However, they have about 30% more sales staff in support roles. While this may seem counterintuitive, this approach frees up sales reps from more administrative tasks, such as order management and developing sales collateral, to devote more of their time to customers. The result is that front lines sales reps are three times more productive than their peers.

One leading high-tech equipment business, for example, found that 28% of sales rep time was spent on low value activities like complaint handling. They then shifted about half of these transactional activities into a sales factory and freed up 13% of sales rep time for them to sell.

Sales executives also need to take a hard look at their sales support systems. Some activities can be automated or streamlined, some can be delegated and pooled into back-office sales factories, and others can be cut entirely. Implementing such operational and structural changes requires a clear understanding of just what constitutes low- versus high-value-add activities and what resources are currently devoted to each.

4. They use as many channels as they can. Companies that effectively sell across multiple channels (inside sales, outsourced agents, value-added resellers, third-party retail stores, distributors, or wholesalers) achieve more than 40% higher sales ROI than companies wedded to a single channel model (only key account management and/or field sales). Managing multiple channels calls for effectively addressing selling opportunities based on value versus on volume, and recognizing that not every channel is optimal for every product. For instance, inside sales reps can handle key accounts with low-complexity products, whereas more costly in-person support should be assigned exclusively to key accounts with high-complexity products.

Many companies are understandably afraid to “tinker with” sales, the only part of the organization that actually brings in the revenue. We believe, however, that more aggressive action to match sales resources with sales ROI opportunities is critical if companies are looking to beat the market.

April 24, 2014

Social Physics Can Change Your Company (and the World)

Sandy Pentland, MIT professor, on how big data is revealing the science behind how we work together, based on his book Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread.

Presentation Tools That Go Beyond “Next Slide Please”

Data visualization luminary and Yale professor Edward Tufte famously suggested that PowerPoint would have been a presentation medium well-suited to a communist dictator. The program’s linear nature, its tendency to discourage interactivity, its inability to easily share the information it contains, and its potential to limit communication with the audience can sometimes obfuscate rather than clarify. Indeed, Microsoft’s recent web-enabled improvements to the longstanding business application suggest that change is coming to presentation tools in a business world increasingly shaped by online collaboration and increasingly powerful internet applications.

Today, users have unprecedented access to data at their fingertips and powerful applications to process them in real time. We use this data for everything from understanding how to set our home thermostats to monitoring NASA satellites in outer space, and we need ways to analyze, visualize, share, and explore data to improve our decision making and way of life. This new need is driving the development of communication and presentation tools, posing a fundamental challenge to the hegemony of PowerPoint.

The best presenters tend to show rather than tell, creating opportunities to engage and persuade. They feature fresh, exciting information. By soliciting feedback and helping listeners feel ownership of the ideas under discussion, they inspire audiences and ultimately create a bond with them. Great presentation tools should have the necessary elements to support questions and intellectual digression, to allow as little or as much data to be presented per idea to communicate effectively, and should discourage the user from accidentally or intentionally “suffocating key data and conclusions” with what Tufte describes as “Chartjunk.”

From nonlinear story canvases to streaming in-presentation visualizations, new online presentation tools provide unique opportunities to do just about anything one can imagine an internet application doing. A new class of digital presentation tools are cropping up to answer these needs.

One of the more challenging aspects of engaging an audience is breaking away from the linearity imposed by past presentation tools. After all, a great presenter’s goal is to communicate and discuss a few key ideas rather than to present a story in its entirety. Traditional presentation tools presume a fixed order, and encourage presenters to move from one slide to the next, regardless of how the audience reacts. But that’s not the only way to structure a presentation. Prezi, a San Francisco based start-up, has created an exciting solution to this problem by creating a descriptive canvas that the speaker zooms into and out of as necessary to underscore the relevant points. This allows the presenter to adapt the storyline in real-time to the audience response, and encourages presenters to solicit audience feedback throughout the presentation. Its radical concept is well executed with beautiful graphics and animations that effectively use motion and slick transitions to keep listeners attentive and interested.

Not only can new presentation tools adjust the order of a presentation, they can also help it stay up to date in real time. Until recently, presentation tools have largely been static, creating an artificial boundary between the presentation and the outside world. With the ability to integrate internet applications into presentations, it is now possible for a presenters to bring the real world into their presentations with simple embed codes to explore current inventory levels, receive tweets, show video, or view real-time stock prices during the meeting. While most modern presentation software allows presenters to embed internet windows into their presentation for real-time browsing, some also allow users to directly embed live data from outside applications. Zoho Show, a component of Zoho Docs, has the ability to allow users to embed pictures, videos and data from 26 online sources, including Salesforce, Facebook, Google, and Yahoo, which update in real time. And in the future, based on the code embed capabilities that start-ups like SlideCaptain are offering, one might one day soon expect the capability to incorporate functionality into presentations from any online source.

Standard presentation tools have even shaped the way we do Q&A, training us to spare presenters questions they cannot reasonably answer during their linear, one-sided presentations. This often happens in research meetings where team members present their findings to a group for constructive discussion of the analysis. With direct and real-time access to the data, as well as to analysis and graphing tools, audience members can discuss and replot datasets from the presentation during the meetings to test hypotheses and move the discussion from a theoretical to a hands-on interactive level. My own company, Plotly, has a platform that creates interactive, collaborative graphs that are attached to specific datasets behind them. Presenters can open the graph during the presentation and examine or replot the data to promote discussion. Plotly also has the added benefit of streaming data into the presentation such that the graphs are always up to date, and real-time data can be viewed or accessed.

The final big change in presentation tools incorporates the level of collaboration we’ve come to expect using document-sharing applications like Google Docs. Online presentation platforms are increasingly common in the business world, allowing multiple creators to build a presentation at the same time. This is a must-have for virtual companies with remote team members, but it is also generally a better way for collocated teammates to jointly author slides. Another feature originally developed for remote collaboration that is also a terrific tool for in-person working meetings is the ability to switch presentation computers on the fly, to allow users in the same room to seamlessly take control of the presentation to display their own screens. This allows impromptu semi-prepared visual input from any meeting participant and can help to democratize meetings and share ideas more effectively.

Many of these tools are early on in their development and so won’t fully replace PowerPoint right away. Microsoft is firmly entrenched and is responding to the emerging competition by incorporating some of these elements. But for top presenters looking to give presentations that are dynamic, collaborative, and real-time — and to incorporate data — the answer is to do more than just add another slide.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How to Have an Honest Data-Driven Debate

The Quick and Dirty on Data Visualization

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious

6 Tips for Reluctant Negotiators

I had been hired to do 1-on-1 speed-coaching sessions at the Summit Series at Powder Mountain, and I was confident I could help one person, in particular, to take his career to the next level. Once back in the office, I pinged him: “I would love to coach you. Any interest in exploring?” He responded enthusiastically. Yes! But when I began to talk terms, he demurred. I didn’t realize this would cost money. I thought you were doing this to be nice. I had been so excited. It wasn’t just about money, but I needed to put a value on my expertise.

After this recent exchange, I realized my negotiation skills needed a refresher course. Serendipitously, I had the opportunity to chat with Hannah Riley Bowles, a negotiation expert, who teaches the course Women and Career Negotiations at Harvard’s Kennedy School. Based on our conversation, here’s my updated crib sheet:

Signal that you are transacting. For most people in the corporate world, unless you are in “sales,” it’s a soft sell. The transaction is implicit as you interact with clients, but you may never have to actually ask for their business. When you are in business for yourself, however, you most definitely do — which means you need to give cues that you are talking business rather than engaging in a social nicety.Bowles advises, “One way to signal that you are talking business and not just acting “out of the goodness of your heart,” is to say things like, “This is the kind of advice that I give to my clients. Or, “Call me if you’d like to explore working together.” She also suggests, “Carry business cards and use them.” I didn’t have cards with me at Summit. Next time.

Sit on both sides of the table. To be successful professionally, you need to command respect – and this involves the ability to negotiate effectively. However, negotiating for oneself makes both men and women less likable – but more so for women. While men who are no-nonsense negotiators are respected and rewarded for this skill, women may be labeled as a tough and unlikeable. (The alternative is being a likeable woman who doesn’t get ahead.) So it’s actually a good sign if women are nervous walking into a negotiation: “It means that you are correctly reading the social environment,” says Bowles.

One way to gain respect while lowering the social cost is to follow the model Sheryl Sandberg used when she negotiated her COO role at Facebook: “I said to Mark [Zuckerberg], ‘You realize you’re hiring me to run our deal teams, so you want me to be good at this.’” Effectively Sandberg told her would-be boss, ‘Don’t hate me because I’m good at negotiating.’ Her follow-up was equally important. “This is the last time I’ll be on the other side of the table.” Bowles dissects her strategy: “Sandberg first explained why negotiating was a legitimate course, and then signaled her concern for organizational relationships.” If you want to negotiate successfully, lay out the logic of what you are proposing within the context of your relationship. Sandberg was effective because she recognized and assuaged the concerns of the other party, and this applies equally for both men and women when negotiating. When it’s not about me, but we, you’re sitting on both sides of the table.

Power up. Overconfident negotiators risk becoming self-centered and oblivious to others’ needs. But underconfident negotiatiors have a different problem: appearing as a supplicant, not a peer. If you’re not yet feeling powerful? Do what Harvard professor Amy Cuddy advises: “Strike a power pose, adopting expansive, non-verbal postures that are strongly associated with power and dominance across the animal kingdom. Think Wonder Woman.” Priming the pump of power allows you to behave as if you expect the deal you are offering will work, which is more likely to result in an optimal agreement for all parties.

Disentangle negotiation from updates. One of the ways you establish your worth is by apprising your counterparts of recent developments. Because reluctant negotiators can be so uncomfortable with touting themselves, even an update can feel self-aggrandizing. The problem is that if you don’t sock away political capital into the bank of your boss’s opinion, you’ll enter a high stakes negotiation at a disadvantage. The question is no longer — how can you be rewarded, but did you achieve? We further disadvantage ourselves if we store up all of our accomplishments until that one big moment, and then, much like children, fling our arms open, saying, “Look what I’ve done! Reward me.” This seems to be especially common with women. And there’s a certain logic to it; women do need to rack up more accomplishments to prove that they are just as qualified as their male peers. However, saving up all those achievements for one big reveal comes across as neediness, not negotiation. Whether you’re inside a corporation or independent, “establish a monthly check-in with your boss or your clients: here’s what we’re doing, where we’re going,” says Bowles. This signals momentum, and people will pay a premium for momentum.Once you’ve already established your worth, you won’t need to toot your horn at the negotiating table.

Excise emotion. When I want something too much, my emotions can take over. Early in her career, Liz O’Donnell, author of Mogul, Mom and Maid, was advised to try this exercise to prevent that from happening: “Point at the conference room table, and say ‘This is a table.’ The statement was neutral and non-controversial. It was almost impossible to attach any feeling to it. After repeating the phrases several times, the coach had her say what she needed to say to her boss, devoid of emotion.” Intense negative or positive feelings can be instrumental in attaining concessions, but in my case, it means I’m the one giving up ground. I have needed a “just the facts, ma’am” approach, as well.

Look to the horizon. “The most important thing as you negotiate is to look at where you want to go,” says Bowles. On some level, I know this, but I haven’t really applied it to my negotiating technique. I’m discovery-driven, I aver. It’s also a little scary to think too far into the future; that requires a long game and the confidence that you actually can navigate to that future. But understanding where you want to end up is critical, because it gives you power to own your career and to be seen as a strong visionary who knows what she wants and how to get it.

Nothing will improve your bottom line, professionally, personally, and emotionally more consistently than being able to effectively negotiate. It’s something you do every single day of your life and involves essential life skills: defining who you are and what you need in your business and personal relationships; learning to give clear signals about what you want (and being able to read those signals from others); understanding the effective use of “no” and “yes”; and knowing how to enrich your life and the lives of those around you. Some of us are good at the “get,” others at the “give,” but a one-sided approach to negotiation leads to fractured and poisoned relationships. Learn to do both and you can begin to build a career (and relationships) that last a lifetime.

April 23, 2014

The Right Colors Make Data Easier To Read

What is the color of money? Of love? Of the ocean? In the United States, most people respond that money is green, love is red and the ocean is blue. Many concepts evoke related colors — whether due to physical appearance, common metaphors, or cultural conventions. When colors are paired with the concepts that evoke them, we call these “semantically resonant color choices.”

Artists and designers regularly use semantically resonant colors in their work. And in the research we conducted with Julie Fortuna, Chinmay Kulkarni, and Maureen Stone, we found they can be remarkably important to data visualization.

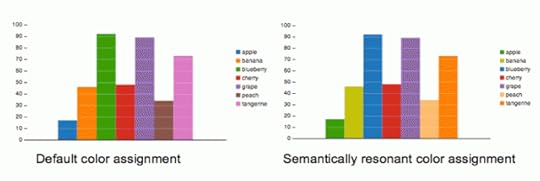

Consider these charts of (fictional) fruit sales:

The only difference between the charts is the color assignment. The left-hand chart uses colors from a default palette. The right-hand chart has been assigned semantically resonant colors. (In this case, the assignment was computed automatically using an algorithm that analyzes the colors in relevant images retrieved from Google Image Search using queries for each data category name.)

Now, try answering some questions about the data in each of these charts. Which fruit had higher sales: blueberries or tangerines? How about peaches versus apples? Which chart do you find easier to read?

If you answered the chart on the right, you’re not alone. To determine the impact of semantically resonant colors on graph analysis, we ran experiments to measure how quickly people can complete data-comparison tasks on bar charts using either default colors or semantically resonant colors. On average, people took a full second less to complete a single comparison task when they were looking at semantically resonant colors (whether chosen by our algorithm or by an expert designer). That may not sound like a lot but it’s about 10% of the total task time. These time savings can add up, particularly for data analysts making untold numbers of such comparisons throughout their work day.

What’s going on here? We see a number of ways in which semantically resonant colors could be helping improve graph-reading performance. First, semantically resonant colors can enable you to take advantage of familiar existing relationships, thus requiring you to use less conscious thought and speeding recall. Non-resonant colors, on the other hand, can cause semantic interference: the colors and concepts interfere with each other (as anyone familiar with the famous Stroop test from psychology knows – the one in which you’re asked to name the text colors of color names printed in conflicting colors: green, red, and so on). Second, because your recall of the concept-color relationship is improved when looking at semantically resonant data, you may not need to repeatedly look at the legend to remember which column is which, and so can focus more on the data itself.

To make effective visualization color choices, you need to take a number of factors into consideration. To name just two: All the colors need to be suitably different from one another, for instance, so that readers can tell them apart – what’s called “discriminability.” You also need to consider what the colors look like to the color blind — roughly 8% of the U.S. male population! Could the colors be distinguished from one another if they were reprinted in black and white?

One easy way to assign semantically resonant colors is to use colors from an existing color palette that has been carefully designed for visualization applications (ColorBrewer offers some options) but assign the colors to data values in a way that best matches concept color associations. This is the basis of our own algorithm, which acquires images for each concept and then analyzes them to learn concept color associations. However, keep in mind that color associations may vary across cultures. For example, in the United States and many western cultures, luck is often associated with green (four-leaf clovers), while red can be considered a color of danger. However, in China, luck is traditionally symbolized with the color red.

There are a few other factors to consider when using semantically resonant colors:

Type of data: So far, we have only discussed data that represent discrete categories. Other data may be numerical or rank-ordered (“poor,” “fair,” “good” for example). In these cases, a diverging or sequential color scheme may be preferred, in which a single color becomes darker or lighter depending on the relative order of the values.

Similar color associations: Some concepts map to very similar colors. For example, “magazine” and “newspaper” might both map to gray. We could consider assigning two different shades of gray to both concepts, but then it may be more difficult to remember which shade of gray maps to which one in the visualization. In this case, we might prefer less-resonant colors that ensure discriminability.

Concept-color association strength: Some concepts are simply more colorable than others. For example, people generally agree on the colors of asset categories such as “gold,” “silver,” “cash.” However, what is the color of “social security,” “national defense,” or “income security”? Overall, we found that using semantically resonant colors for categories that were more colorable unsurprisingly tends to provide greater performance improvements.

Semantically resonant colors can reinforce perception of a wide range of data categories. We believe similar gains would likely be seen for other forms of visualizations like maps, scatterplots, and line charts. So when designing visualizations for presentation or analysis, consider color choice and ask yourself how well the colors resonate with the underlying data.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How to Have an Honest Data-Driven Debate

The Quick and Dirty on Data Visualization

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers