Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1442

April 8, 2014

Four Ways to Adapt to an Aging Workforce

Calls to maximize the utility of older workers — by honoring experience, providing training opportunities, and offering flexible work and retirement options — began to sound at least a decade ago. HBR contributors have suggested we “retire retirement” and “adapt for an aging workforce.”

But proposing reform is one thing. Instituting it is another. Have companies followed through? Our analysis suggests that some are starting to. We’ve found four best practices for accommodating older workers that should serve as a model for other organizations:

Flexible, half-retirement. Although retirement reform remains stagnant at the policy level, companies are being more proactive about modifying employee exit schemes. For example, Scripps Healthcare has installed a phased-retirement program: Retirees work part time, while drawing a portion of their retirement funds, so they still effectively earn a full salary and benefits. Meanwhile the company avoids having to hire expensive temporary workers and retains talented employees in areas where skills are scarce. WellStar Health System offers a similar option for employees who have been with the company at least ten years.

Prioritizing older-worker skills in hiring and promotions. Companies like Vodafone are putting more emphasis on employees’ loyalty, track records, competence and common sense, all commonly found in older workers. Vita Needle does the same, noting that loyal older employees not only enhance the company’s reputation, but also yield higher quality work and attention to detail. B&Q (winner of the 2006 “Age Positive Retailer of the Year” Award) says that it hires for soft skills , such as conscientiousness, enthusiasm and customer rapport, which senior workers also seem to show in abundance, while Home Depot famously looks to older store clerks for the experience-based know-how that customers demand. And these aren’t just perceptions: A report from the Sloan Center on Aging & Work at Boston College has found that, compared to younger workers, older workers do have higher levels of respect, maturity and networking ability.

Creating new positions or adapting old ones. Migros Geneva retrains employees for jobs that better suit their aging skillsets—for example teaching a 58-year-old former cashier to be a customer service representative—as outlined in this article. Marriott’s Flex Options for Hourly Workers program offers a similar service, helping 325,000 older “associates” around the world transition out of physically taxing roles by teaching them new skills on the job, while United Technologies invests $60 million dollars annually in its Employee Scholar Program. And Michelin rehires retirees to help oversee projects, foster community relations, and facilitate intergenerational mentoring. This strategy works at the executive level, too. HPEV, the intellectual property and product development company, recently formed a Strategic Advisory Board headed by a recent retiree, Dick Schul, recognizing the value of his 43 years’ experience in the industry. Other companies, such as ExecBrainTrust, specialize in matching recently retired executives with temporary consulting roles.

Changing workplace ergonomics. Although not all older workers are feeble, companies can and should adapt for those who need some extra support. BMW has made inexpensive tweaks to workplace ergonomics for older employees (think wooden assembly-line floors, custom shoes and easier-to-read computer screens), as described in this post. Another example comes from Xerox, which recently introduced a training program to teach better ergonomic health strategies and raise awareness about the normal aging process. Unilever UK has also instituted a wellness program designed to prolong the working life of its older employees.

Companies that make these changes have seen tangible improvements in retention and productivity, organizational culture, and the bottom line. Since B&Q began actively recruiting older workers, its staff turnover has decreased by a factor of six, while short-term absenteeism is down 39%. Leaders say its growing ranks ofolder employees have been integral in creating a friendlier, more conscientious work environment. And profits are up 18%. Following its ergonomic changes, BMW has seen productivity jump 7% and its assembly line defect rate drop to zero. United Technologies has boosted its older worker retention rate by 20%, and Unilever UK estimates that it gains six euros in productivity for every one euro spent on wellness. Companies with high over-50 employment rates—at both the staff and executive level—are also proving to be leaders in their respective industries. Michelin and WellStar Health System are two examples.

Given demographic trends in the developing world, corporate workforces are set to age significantly in the next few decades. Is your organization ready to adapt?

In France, Grape Growers Use Price to Punish Nontraditional Winemakers

Economists would have you believe that prices are determined by economic forces, but sometimes they’re used as rewards and punishments. In France, many of the 15,000 Champagne grape growers charge less to those among the 66 Champagne makers that fit the traditional mold of being old and independently managed by descendants of the founders, and that don’t produce supermarket brands. Makers that violate these unspoken rules typically have to pay as much as several euros per kilogram more for grapes, a substantial markup, given that the average price is 9 euros, say Amandine Ody-Brasier of Yale and Freek Vermeulen of London Business School.

How African Firms Can Make the Most of Outside Investment

Trade between Africa and China surpassed $200 billion this year, strengthening China’s position as Africa’s biggest trade partner, a position it has now held since 2009. Less than 15 years ago, the corresponding value was a modest $10 billion. This statistic demonstrates the growing pulling power that Africa holds for foreign investors. Beyond trade relationships, investors increasingly look at African consumers and see immense opportunity to invest locally. For African companies, this presents a special chance to climb the food chain of global competitiveness.

After all, many of China’s present national champions began life as local partners in joint ventures with Japanese or Western operators. They successfully navigated the path from being local tour guides to competing on the forefront of many global industries. Similar windows of opportunity are opening across Africa today. A decade ago, most of China’s economic activity in Africa was situated at the level of government contracts (mostly delivered through state-owned enterprises) or haphazard imports from small-scale entrepreneurs. Today the ‘middle corporate’ sector is gaining traction. For example, Chinese special economic zones have been set up as far apart as Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa in joint cooperation with local firms, and Chinese factories are going up in many more nations. The Chinese are not the only ones in the mix − Indian, Brazilian, Israeli, and Western companies are setting up shop, too.

How can African companies capitalize on this opportunity? The key is to shift priorities away from short-term profits and towards longer-term autonomy by creating institutional memory and integrating around customer needs.

Create institutional memory. Foreign operators bring with them processes, operating models, and organizational cultures. The better the local partner can internalize (and adapt) these best practices to their business model, the greater the chance of autonomous success. Best practice transfer happens across all layers of the organization: people, technology systems, compensation, working practices, etc. A metrics dashboard should be used to track progress across all these layers.

Seek integration. By orienting towards greater control and value chain integration, local partners signal to the external market and, more importantly, their managers and staff that they want to be leaders and not followers. This helps with a process of self-selection amongst both investors and employees, leaving those that are willing to be pushed outside their comfort zone and have patience for a longer-term game.

It may seem that pursuing this strategy puts local firms at odds with the foreign partners they work with. But there are many reasons why this is a short-sighted view:

Competition grows the market. Foreign operators who breed independent local competitors often find that the local firms choose to grow the market in areas of non-consumption, rather than competing head-on.

Strong local partners are better at customer innovation. They understand customer needs better and may help the foreign operator garner unique insights that can be deployed elsewhere.

A reputation for sustainable partner development has its rewards. Governments and other local companies will prefer foreign partners with a track record of leaving strong domestic partners.

Today, most of Africa’s local partner firms have not positioned themselves to be able to stand on both feet following joint ventures with foreign operators. Some macro factors contribute to this, including the absence of effective government regulation or coordinating capacity through associations. Nevertheless, many African companies can do much more. There is a new Africa gold rush underway, and the local firms that can build successful partnerships will find the path to success.

April 7, 2014

The Key to Lasting Behavioral Change: Think Goal, Not Tactic

Why can’t I force myself to go to the gym before work? Get my high-priority work done before I check my email? Stop letting my expense reports pile up? Why am I so bad at changing?

Even the most motivated people can get stuck, frustrated, and lose hope during the process of behavioral change. As a time coach, I see this happen when clients become so fixated on specific tactics — getting up at 5 am, say, to make time for the gym, or a hard-and-fast rule that they never check email before 10 am — that they lose sight of the fact that many methods could lead to achieving their larger strategic goals.

Yes, habit change takes discipline, patience, and practice. But no, it shouldn’t feel like you’re constantly trying to force yourself to do something you really don’t want to do. That’s unsustainable. To make new habits stick, they must work with the reality of who you are and what’s best for you.

To identify tactics that will actually work for you and keep your focus on your big objectives, start by determining where you’re stuck. Identify a few areas where you’ve seen little-to-no behavioral change despite your best efforts — for example, blocking out whole days for big projects or going to the gym first thing in the morning. Then zoom out to determine your real goal. Why was this activity important to you in the first place? Maybe you want to feel like you’re finishing priority tasks, or have a healthier, more physically active life.

Now brainstorm other tactics you could use to achieve those goals. If you’ve never managed to block out an entire day for your major projects, try finding two half-days instead. If you hate the gym or aren’t a morning person, don’t expect yourself to go there first thing in the morning! Instead, consider options like a bike ride after work or exercises you can do at home before bed. Identify activities that align with your natural tendencies.

You may need to try out a few different tactics until you discover when you can be most consistently effective. Test one of your hypotheses each week. For instance, you could try going for a bike ride after work for one week, and then the next week see if you can do exercises at home before bed. Observe what seems to fit most naturally with your schedule and motivation levels. Arrange your schedule in different ways and see what produces the best results. Once you’ve identified that sweet spot, guard that time from meetings and other activities.

If you need accountability, get it. Top performers embrace this reality and surround themselves with strong teammates and assertive assistants. They know that these individuals will help shore up any weaknesses and allow them to fully use their strengths. There’s no shame in surrounding yourself with people who will check in on you and ask you about the status of key projects or goals, whether that means hiring a good project manager or a motivated personal trainer.

But if there are tasks that you really struggle to do, delegate them or outsource them. It’s better to not spend willpower energy forcing yourself to do what other people can do for you. Save that effort for activities you can’t transfer to anyone else. Make a list of activities that you tend to fall behind on, such as filing expense reports, setting up meetings, or updating tracking documents. Then, see if you can find someone within your organization, an outside contractor, or a technology tool that could take these items off your list. If necessary, clear this strategy with your boss before proceeding. When it comes to chores like errands, you can do everything from ordering groceries to having shampoo delivered automatically online from Amazon. You can also hire assistants to do activities from organizing an event to picking up dry cleaning through companies like TaskRabbit or Fancy Hands.

By staying focused on the goal and experimenting with tactics, I’ve seen people who have never kept routines start to exercise consistently, make progress on priority projects, get on top of e-mail, and accomplish all sorts of other goals. Keep these principles in mind, and you can—and will—achieve lasting behavioral change.

Why Family Businesses Come Roaring out of Recessions

The family business is still widely regarded as an ineffective organizational form (read this, this, or that paper), especially in the US, even though recent evidence challenges this perception. Some studies (see here or here) have shown that during periods of economic growth, family-managed companies in the US actually perform better than professionally managed businesses.

However, a rising tide lifts all boats; it’s the ebbing tide that reveals the truth. Just how do family businesses perform during recessions, when only the strong survive?

To answer that question, we compared the performance of 148 publicly listed family-owned companies between 2000 and 2009 with that of 127 non-family businesses using Standard & Poor’s Compustat database. Of course, the National Bureau of Economic Research classified two (2001 and 2008) of those 10 years as recession years.

We found that family businesses handily outperformed non-family companies during both the 2001 and 2008 recessions in terms of a key metric, Tobin’s q. (Tobin’s q is the ratio between a company’s market capitalization and the replacement cost of its tangible assets, with a higher ratio indicating that a company has more intangible assets such as patents, brands, leadership etc., and is likely to grow more in the future than one with a lower Tobin’s q.)

For instance, in our sample, the average Tobin’s q of all the family businesses remained at 1.9 regardless of the economic cycle, but that of the non-family corporations dropped from 1.2 during the growth years to 0.8 during recessions. Thus, the former coped better with the recessions than the latter. The family companies’ edge remained after we controlled for a number of factors such as company size, age, level of globalization, level of diversification, R&D intensity, and industry. It held true for both founder-managed companies, such as Dell and Microsoft, as well as for multiple family-member-managed corporations such as Walmart and Federated Investors.

We also found three differences in marketing strategies, which may account for the performances of the two types of companies.

1. Family-owned businesses did not hold back on new product launches during the recessions. Data from several sources such as the Capital IQ database, Factiva, and LexisNexis revealed that they introduced 12 new products a year, on average, regardless of the economic cycle whereas launches by non-family companies fell from 14 a year during the boom years to just eight on average during the recessions.

The family businesses’ proactive approach clearly helped them do better. Not only is it easier to differentiate brands when there is less competition, but also, products introduced during recessions will enjoy a first-mover advantage as the economy recovers.

2. Family businesses maintained almost the same levels of ad-spend during the recession years as they did during normal times, helping them do better than the professionally managed companies, which reduced ad-spend when the times got tough. In our sample, the average advertising intensity (advertising expenditure divided by total assets) of the family companies fell marginally, from 2.0% during the non-recession years to 1.9% during the recessions. The same metric for the non-family companies plunged from 1.4% during the non-recession years to 1.0% during the recessions.

3. Family businesses maintained their emphasis on corporate social responsibility regardless of the state of the economy. Corporate social responsibility can be measured by counting companies’ social strengths — launching social initiatives such as philanthropic contributions, health and safety programs for employees, etc. — and social concerns such as controversies like workforce reductions, violations of environmental regulations, etc. Companies with a high number of social strengths and a low number of social concerns can be said to deliver high levels of social performance.

Customers penalize companies when they don’t maintain high social performance levels, especially in uncertain environments. Data from the KLD STATS database revealed that the family businesses in our sample maintained the same number of social strengths and social concerns during the two recession years while the non-family companies’ social strengths decreased from 3.4 to 2.7 and their social concerns shot up from 4.2 to 5.0.

Family businesses’ proactive actions and long-term perspective during recessions are driven partly by a unique concern for future generations and an emphasis on preserving the family name, but there’s no reason why other companies can’t emulate them. By being more proactive in their marketing and by maintaining their focus on social responsibility, any non-family company can minimize the impact of a downturn. But most don’t — because their leaders’ don’t have the same motivations, which is the essence of the difference between family and non-family businesses.

Which Customers to Listen to, When

AOL, Nokia, RIM, Kodak, DEC. All the same story: once-great companies that suffered disruption. In business, if you’re not listening to the right customers, it can all disappear before you realize what’s happening.

Many modern businesses take stock in the reality of disruptive innovation and try to react accordingly. In the software industry, giants like Microsoft, SAP, Oracle, and IBM have all invested heavily in the cloud technologies that are disrupting software. In car rentals, firms like Hertz and Enterprise are making bets on car-sharing operations. Even dominant businesses like Amazon and Facebook spend enormous sums of money to snatch up and independently operate disruptive businesses like Quidsi and Whatsapp. But in almost all of these situations, the threat is clear and present by the time an investment is made.

So, the question is, why — with a strong understanding of the dynamics of disruption — are we still so slow to move?

Pundits and managers alike readily cite reasons including the stresses of business model innovation or the difficulty of making small experimental investments inside the four walls of an established organization. I don’t believe these answers.

In my experience, I’ve never seen a stalwart executive fail to tear down these barriers when conscious of the significance of the change on their doorstep. With an understanding of disruption, leaders don’t want to relegate themselves to slow decay simply for reasons of organizational friction. That’s not the legacy executives hope will be recorded next to their names on the pages of the Wall Street Journal articles and Harvard Business School case studies — inaction and powerlessness.

My experience points me toward another answer: Most businesses aren’t listening to the right customers. Most businesses spend their time listening to their most demanding customers — not only because those customers tend to be the most profitable, but also because our listening techniques direct us towards the customers who speak the loudest. And we end up ignoring — sometimes not even hearing — other customers who may become equally valuable in the future.

It’s the way we listen that allows good companies to get eaten from the ankles up; forced to react, not anticipate. To get ahead of disruption, managers need to fundamentally change how they gather customer feedback.

Steve Blank often likes to point out that start-ups are entities formed to identify product-market fit. In the early days, an organization’s very survival hinges on its ability to hearing what the market wants. Once they discover what that is, along with their target market, success becomes a game of execution. Our quest for “understanding” disappears unless it is driving growth and profitability.

When there are no disrupters on the horizon, management’s singular focus on growth and profitability doesn’t interfere our ability to listen to the market and predict the future. Customers who have the largest demands will tell us so in sales meetings and reinforce their message when they vote with their wallets. Customers that companies would normally neglect, those that offer lower profitability – those who feel like we’re providing more functionality than they need – will also tell us so in the form of customer complaints and negative social sentiment. Because, before disruption is on the horizon, there is generally no other game in town. For a real-world example, just consider the airline industry. For the most part, there still are no good alternatives to air travel and far too frequently, the disruptive point-to-point carriers simply don’t fly the routes that compete with the major incumbents. So the airlines court the opinion of their premium flyers and are able to sort through the complaints from of the rest of us who are forced to fly around the country with lost luggage.

Before disruption, feedback abounds. But the listening techniques that companies naturally employ in their early days are utterly inept to direct strategy once a disruptive entrant enters the arena with a credible substitute for upmarket competitors.

Once a disruptive substitute emerges, the paradigm changes. Instead of complaining, customers at the low end of the market can simply leave. They no longer feel captive, as if their only option is to yell as loudly as possible in order to be heard. They don’t feel an emotional investment. They simply feel like they made a temporary decision, and its time to make a new one. So they exit.

Albert Hirschman described this phenomenon in his essay, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. He used economic theory to explain trends he saw in both business and politics. One of his insights was that as the market changes and new options emerge for your customers, so too must your listening tactics and your approach to building customer loyalty. This is where most of our organizations fall down. As disrupters emerge on the scene, we simply trudge along expecting the same listening and prioritization tools to guide our operations. But those tools fail us in understanding what our customers see in these new entrants.

Customer surveys are unlikely to drive engagement from the bottom of the market or the customers who’ve long since abandoned the platform. Social listening is likely to collect input from customers who feel invested or captive in our solutions, not those that are on the verge of leaving for greener pastures. Sales feedback will tend to focus on the best, most profitable, customers, neglecting the voice of the meager customers with no appetite for solutions from the current portfolio.

Keeping a company from faltering in the face of a disruptive entrant requires awareness that only different listening practices can provide. Whenever I’m approached by a firm trying to anticipate disruption, I suggest three tactics to improve listening practices — tactics that we could all benefit from.

Religiously conduct customer exit interviews. The customers who opt to buy different products instead of your own are those who can tell you the most about the appeal of those products. Those customers can articulate where you fell short and where others did better. Often, to identify who these customers are, you need to set up different types of listening systems. Put people in stores to observe purchases, send email questionnaires to customers who haven’t visited you in a while to solicit their opinions. Have an honest and open conversation about where you fell short.

Strengthen engagement tools for low profit customers. Many organizations do a great job at bringing their best customers into the discussion when it comes to the next generation of product or service. The gaming industry looks to blogs and conventions to understand how the “hardcore” gamers will react to improvement. But when it comes to disruption, you need tools to engage those in other segments of the market. You need to identify who’s on the margin of your business and actively open channels for communication with them. Start advisory groups and user communities intentionally populated with people who only engage with your core products peripherally. They won’t feel as invested as your best customers, so you’ll need to make sure you do the work to get them involved and contributing feedback. Unfortunately, if you don’t do the work, you may remain stuck in the echo chamber associated with daily business.

Use the data time machine to predict competitor growth. Your business likely grew up out of the low end of a market, once upon a time. A powerful tool in understanding the appeal and threat of your competitors is revisiting your own history. If the customers that are leaving today had left 10 years ago, what would have been the impact on your growth? If they’d left 20 years ago, how much profit would have been lost? Would you even be in business today? This type of listening to economic indicators can both help you understand the speed and scope of your disruption as well as position the significance of the threat to your executives. There is no better tool than a rational and realistic description of risk to get large companies to move.

Adapting to disruption is never easy. But it is possible to be aware of the threat far before it’s tearing your business apart. The key is understanding which customers you naturally listen to, and to focus some of your listening on those that you don’t before its too late.

The Problem with Being Too Nice

Leaders are placed under a tremendous amount of pressure to be relatable, human and … nice. Many yield to this instinct, because it feels much easier to be liked. Few people want to be the bad guy. But leaders are also expected to make the tough decisions that serve the company or the team’s best interests. Being too nice can be lazy, inefficient, irresponsible, and harmful to individuals and the organization.

I’ve seen this happen numerous times. A few years ago, a senior staff member of mine made the wrong hire. This can happen to anyone, and the best way to remedy the situation is to address it quickly. Despite my urging to cut the tie, this staff member kept trying to make it work. While I laud the instinct to coach, fast forward two months later, and we were undergoing a rancorous – and unnecessary – transition process. There’s a key lesson here for any leader. Nice is only good when it’s coupled with a rational perspective and the ability to make difficult choices.

Here are a few other other recognizable scenarios where being nice isn’t doing you – or anyone – any favors:

Turning to polite deception. You’ve been in these brainstorming meetings – everyone is trying to hack a particular problem, and someone with power raises a ridiculous idea. Instead of people addressing it honestly, brows furrow, heads nod like puppets on strings, and noncommittal murmurs go around. No one feels empowered to gently suggest why that particular idea won’t work. At my company, rejecting polite deception is a big part of how we do business. When something isn’t right, we call each other out on it respectfully, then and there, without delay. Why? It’s not helpful to foster an everyone-gets-a-trophy mentality; you have to earn the honors to get the honors.

The long linger. Sometimes a hire just won’t cut it in a certain role. It might seem easier to keep an employee in place rather than to resolve the mismatch – but it actually is not. Resist the temptation to prolong confrontation, to see if things will get better. It is more of a disservice to let someone flounder, especially when it’s clear that he or she just isn’t hitting the mark. Be kind and communicate clearly, but don’t be nice. Be surgical about it. Make the clean cut. Help the person transition somewhere he or she can succeed. Handling employee issues immediately helps your culture and productivity – over time, you’ll attract employees with similar values and convictions.

Don’t be a doormat. When you’re too nice – to suppliers who can’t deliver on time, to colleagues who don’t do their work, to customers who refuse to pay – you’re actually letting others take advantage of you and your business. When you’re overly generous with your allowances for others, you create a fertile atmosphere for contempt to spread. Imagine the reactions of your most talented, focused, and motivated employees as they watch lackluster coworkers get pass after pass. Anger and resentment take root, morale plummets, and turnover starts to go up, up, up. Think of how loyal customers will react if they see how easy it is for others to take advantage of your services. Your reputation will surely suffer. These problems become more difficult to solve as they pile up. You don’t need to be severe to be respected, but you do need to hold your organization to certain standards — and you must be firm about people meeting them. Setting rules will help you when decisive action is needed. No more delays, no demurring, no debating.

Failing the introspection test. Are you too nice to yourself? Introspection is a powerful leadership tool, but we often forget to use it. When you ask yourself what behaviors hold you and your team back, you can recalibrate your leadership style for the better. When you give employees the space to give you the hard truths, without fear of repercussion, you’ll get valuable perspective and make a giant leap forward in maturing as a leader.

Of course, this doesn’t mean managers get a free pass to be disrespectful, cruel, or a bully in the workplace. There’s a world of difference between being an effective leader with high expectations and dealing with problem after problem caused by milquetoast management. Beware of confusing being nice – or being liked – with being a good leader.

A Simple Theory for Why School and Health Costs Are So Much Higher in the U.S.

The costs of education, health care, and the live performing arts are growing at about the same rate in all the OECD countries—and yet the costs of these services are much higher in the United States. For example, U.S. total educational spending, as a share of GDP, is about is 26% higher than the average of the other OECD countries. A team led by Edward N. Wolff of Bard College points out that because the humans who provide these services aren’t replaceable by machines, costs tend to rise inexorably, and that America got a long head start on spending in the nineteenth century when a rapidly expanding economy led to huge expenditures on universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions.

How to Adapt to American-Style Self-Promotion

Imagine you’re at a networking event in the United States and you hear your colleague make the following statement to a potential employer:

“… I’d be very interested in learning more about your company to see if there might be a fit for me. Before doing my MBA, I worked at Bain Consulting and then prior to that was an officer in the army…”

Understanding that this is only a portion of the conversation, how would you judge what you happened to hear? As:

(a) Too self-promotional: the person is speaking too positively about himself for the situation.

(b) Not self-promotional enough: should give more details at this point in the conversation about specific accomplishments at Bain (such as projects completed or impact on clients) as well as additional information about military service.

(c) Just about right: This is self-promotional, but the context allows it and the person is providing appropriate and relevant information to position himself in a positive light.

Typically, most Americans choose option C. Sure, it’s a bit self-promotional, but this is taking place at a networking event, so the potential employer is probably expecting comments like this. What’s interesting, however, is the reaction Andy often gets from his foreign-born MBA students about the same scenario. To many of them, the language feels overly self-promotional — like the person is really boasting about himself in an inappropriate manner. And this points to a thorny cross-cultural challenge many foreign-born professionals face here in the United States, especially when networking or interviewing: the challenges of American-style self-promotion.

It’s hard to quantify, but we believe the United States is the most overtly self-promotional country in the world. Certainly there is variance among cities, regions, industries, and especially individuals. But overall, American professionals are often quite comfortable promoting themselves, especially in a business environment — and that behavior is actively encouraged as a sign of competence and self-confidence. That’s simply not true in most other countries and cultures, from East Asia to Latin America to most of Europe. Even in the United Kingdom, where we share a language, Andy’s research has revealed that overt, American-style self-promotion is taboo.

But here’s the challenge: Many young professionals strive to find work and progress up the organizational ladder here in the United States. And to do that, they need to learn to self-promote. In interviews and at networking events, they need to emphasize what they themselves have achieved and accomplished (opposed to emphasizing only what the “team” has accomplished). And when on the job, they need to self-promote to a certain degree, to establish a reputation as someone who can add value and contribute to the bottom line.

So how can young, foreign-born professionals learn to act outside their personal and cultural comfort zones to promote themselves and their accomplishments?

First, as we discussed in our previous post, “Self-Promotion for Professionals from Countries Where Bragging Is Bad,” it’s important to reframe your concept of personal branding. If you think of it as phony show-boating, you’re never going to want to even attempt it, which means you’re missing out on the professional benefits of being recognized by others. Instead, focus on the big picture — such as making a difference and helping your company — and you’re far more likely to want to make an honest effort.

Next, make sure you understand the actual level of self-promotion that’s acceptable and appropriate for the specific situation you find yourself in. Because many foreign-born professionals are so shocked by American levels of self-promotion, they often overestimate how much is being done. The danger is that when they dive in and attempt it themselves, they risk overcompensating. What they miss is that there is a zone of appropriateness and acceptability for self-promotion, even in American culture, and that when you go outside the zone, you’ll be seen as arrogant and boastful. So make sure you recognize the “zone of appropriateness.”

It’s also critical to learn your own “personal comfort zone” with respect to these rules. How much of a gap is there, for example, between how you’d naturally and comfortably act in a given situation and how you need to act to be effective? And if there is a gap, as there is with so many foreign-born students and professionals we work with, you will need to develop a strategy for bridging this gap. Perhaps you can create rules of thumb to follow in certain situations. For instance, if you meet someone at a networking event and they ask a question about how you’re spending your time, you can be sure to mention your involvement in your alumni group — which simultaneously shows that you’re an active and engaged professional, and highlights your affiliation to a top-tier school. And at a very basic level, don’t be caught flat-footed when someone asks, “What have you been up to lately?” Be sure to have a good answer ready, so you can demonstrate your expertise.

Finally, find yourself a cultural mentor who is familiar with how self-promotion works in the US and, ideally, who can also empathize with the challenges that you face as an outsider to this culture. Good cross-cultural mentors are worth their weight in gold. They can help you master the new culture code, identify your own personal comfort zone, diagnose the gap you experience between how you need to act and how you’d typically act, and then help you strategize solutions.

In no time, with these pieces in place, you’ll be able to self-promote in a way that doesn’t make you feel like you’re losing yourself in the process.

April 4, 2014

Design Can Drive Exceptional Returns for Shareholders

It used to be about “us” and “them.”

“Us” were the people who believed that design could add significant value when tightly integrated with other business processes. “Them” were the majority of managers who didn’t get what design was all about in the first place.

Today, however, the distance between “us” and “them” is getting smaller. And with good reason: From Target to Uber, business managers everywhere are starting to understand that the strategic use of design is making a difference in achieving outsized business results. At the same time, design is notoriously difficult to define, tough to measure, and hard to isolate as a function.

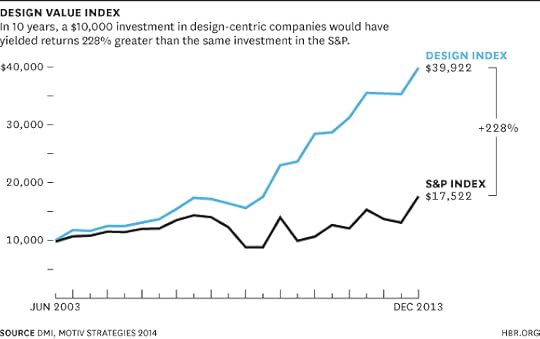

To better understand how design leads to returns, my company, Motiv Strategies, and the Design Management Institute worked together to produce a new tool that tracks the results of design-centric companies against those that are not. Called the Design Value Index, it shows that 15 rigorously-selected companies we believe institutionally understand the value of design beat the S&P by 228% over the last 10 years.

The index was constructed in the same fashion as other indexes that seek to isolate an industry sector (banking, biotech), geography (China), or size (large cap), for example. In our version, we sought to identify only companies that are design leaders. Starting with a list of over 75 publicly-traded U.S. firms, we found only 15 that met our six criteria: publicly traded in the U.S. for 10+ years; deployment of design as an integrated function across the entire enterprise; evidence that design investments and influence are increasing; clear reporting structure and operating model for design; experienced design executives at the helm directing design activities; and tangible senior leadership-level commitment for design. Corporations who made the index based on this criteria include Apple, Coca-Cola, Ford, Herman-Miller, IBM, Intuit, Newell-Rubbermaid, Procter & Gamble, Starbucks, Starwood, Steelcase, Target, Walt Disney, Whirlpool, and Nike.

The latter company is a great example of what it looks like to place design at the center of corporate strategy. At Nike, a large and well-resourced design function reports directly to CEO, Mark Parker, who early in his tenure was a designer himself. Virtually everything the company makes, and is thinking about making, is highly influenced by this huge team of footwear, product, fashion, store, graphic, interaction, and brand designers. Using human-centered design methods, inspiration for the company’s signature products is drawn directly from its cadre of famous and not-so-famous practicing athletes, with whom the designers directly interact with to devise authentic performance innovations and style updates.

In fact, no other company function is allowed to second guess the design team’s direction when it comes to the emotional and functional benefits for consumers, the interpretation of market trends, and, of course, aesthetics. Design is expected and trusted to lead Nike.

This is not to say that design “runs” the company, however. Rather, design is a highly influential force that, when effectively integrated with strategy, marketing, and so forth, can help the company stay out in front of its competitors by staying close to customers and commanding handsome price premiums. Of course, design also has a huge impact on the representation of Nike’s brand across the globe. Countless acts in the design details ladder up to one big, fat impression that Nike is the company for performance-minded athletes.

How can this type of commitment to design contribute to results? In Interbrand’s 2013 list of the World’s most valuable brands, Nike ranks 24th, two slots up from the prior year and a 13% increase in value to $17.085 billion. Next to Apple, Nike had the highest shareholder returns in our index — from 2003- 2013 Nike’s market cap increased from under $6 billion to $70 billion, or 1,095% over the last ten years. Further, Nike was ranked the #7 most innovative company by Fast Company in 2014, and the 13th most admired company by Forbes magazine.

The bottom line is that companies that use design strategically grow faster and have higher margins than their competitors. High growth rates and margins make these companies very attractive to shareholders, increasing competition for ownership. This ultimately pushes their stock prices higher than their industry peers. The returns in our Design Value Index were 2.28 times the size of the S&P’s returns over the last 10 years. Neither hedge fund managers, nor venture capitalists, nor mutual fund managers came anywhere close to these results.

And thanks to the exemplar companies included in our index, as well as many international firms like Samsung, Ikea, and BMW, consumers now recognize, expect, and will pay for good design. This goes beyond traditional consumer products; government and B2B marketing, notorious for not-so-great aesthetics and customer experiences, are starting to make design a priority.

As a person who has spent part of her career helping companies appreciate and use design to their advantage, I will be the first to tell you that making it a central part of strategy isn’t always easy. But now that we know a lot more about how integrated design drives returns, companies across sectors can start thinking about managing design strategically at the enterprise level. There is clearly much value to unlock, and the only way to do this effectively is to do it together. I want no more talk of “them,” just “us.”

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers