Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1452

March 18, 2014

Family Business Owners Must Set the Agenda (Without Micromanaging)

“It’s our money.”

With those three little words, Charles changed the course of his family’s shipping business**, highlighting the role that owners can play in a family business. His father had founded the business in the 1960s and, after building it to $500 million in revenue, had passed ownership down to Charles and his four siblings, then stepped away from the executive suite and ultimately from the board.

This may seem like the perfect succession; in fact, it was a perfect set up. The five siblings couldn’t get real control over the business. The non-family CEO – selected by the father – had gotten used to running the company with minimal direction. Board seats, too, were filled by their father’s friends, some of whom doubted the business capabilities of the next generation. True, the siblings chose a new chairman and replaced some board members. But they still struggled to put their mark on the business.

Then something happened. At a priority-setting meeting of their Shareholder Council, Charles got fed up listening to all the talk about how to convince managers to do things the way that the owners wanted. He put a stake in the ground. “Why are we cow-towing to the managers?” he said. “It’s our legacy. It’s our money.”

The tectonic plates began to shift. The siblings clarified their hopes for the business in a vision statement. They pushed management to change the metrics they used for measuring success from a focus on gross earnings to an emphasis on returns on their invested capital. They began to take charge over some critical decisions and worked with the board to implement them. There were inevitably some squabbles, but ultimately management adjusted to the greater role that family members wanted to play in the business that they owned.

Don’t get us wrong. We’ve worked with businesses where the owners can sabotage the success of the enterprise. There’s even a famous Harvard Business School case – J. Perez Foods – on the subject. In it, a family owner named Mercedes starts interfering in HR decisions, firing the employees she doesn’t like. Ironically, while the case is written to point an accusatory finger at Mercedes, when we’ve taught the case to business families, class participants often blame Mercedes’s father, who failed to find an appropriate role for his daughter in the business. That’s what sent her down the path of looking for grossly inappropriate ways to exercise some power.

Our experience in the classroom brings us back to Charles and the question: “What is the appropriate role of the owners of family businesses?” Our view is that the most successful owners must make a small number of very important decisions. They are to:

Set the goals for the business. Many family business owners don’t focus solely on economic returns, but also on jobs for their families, liquidity for their lifestyles or outside investments, or contributions to the community. Owners need to spell out their objectives, knowing that otherwise the business may end up serving somebody else’s interests.

Define the metrics to measure the business’s success. Owners often receive too little or too much information. To get just what they need, they should develop a dashboard that allows them to monitor business performance – and then have a regular venue in which to discuss those results.

Hire the board. Though it’s often forgotten, the board’s primary job is to protect the owners’ interests. Therefore, the owners need to design and oversee the process by which board members are selected and evaluated. This process is complicated by the fact that owners themselves often sit on boards, and therefore need to be acutely conscious of, and conscientious in, separating their roles and responsibilities. This means very clearly establishing criteria for what gets discussed where.

Determine the dividend policy. The board generally makes the annual decision about dividend payouts, but owners should define the policy and share their preferences with the board about what portion of profits to reinvest rather than take out. This is important: in the absence of the rigor of the market place, dividend policy is a means of enforcing discipline on management through the constraint on resources that management can access for the business.

Beyond this, the best owners do not meddle: they delegate decision-making and let the board and management do the jobs they’ve been hired for.

So how is your ownership group doing? Here’s a quiz from our client work. Score your owner group on each question, “3” being doing extremely well to “1” being not at all.

Choosing your goals

Do you discuss and write down the specific objectives you want to accomplish together – e.g., growth, liquidity, family employment?

Have you established and communicated to the board and management clear guidelines about the goals they should pursue?

Tracking performance

Have you agreed on the top 3-5 measures of the company’s performance? Do you have a scorecard ready?

Does this scorecard compare performance with your company’s peer group?

Do you have a process for regularly discussing company performance where your views will be heard by the board/management?

Hiring the board

Do you actively choose board members – i.e., consider multiple candidates, set clear criteria, and hold discussions about candidates’ qualifications?

Does your board clearly represent the interests of owners rather than of management?

Have you clarified which decisions you will delegate to the board and to management and which ones you will stay involved with?

Setting distribution policy

Have the owners discussed, written down, and communicated to the board a distribution and/or dividend policy?

Do you have an annual conversation where you discuss among yourselves your preferences for receiving distributions/dividends vs. reinvesting in the business?

For our clients, we have found that a score of 25 or more means that they are well in control of their companies. A score of 15 to 24 indicates that they’ve not yet found the way to be effective owners. A score of 14 or lower suggests that they have lost control of their company or are at risk of doing so. If you had trouble with some of the survey questions because your board and owner group are one, you have uncovered a fundamental problem.

Where do you fall on the survey? Are you minding your own business?

**Some identifying details about this business have been changed to protect client confidentiality.

Which Women Are Rising to the Top?

It’s the responsibility of management to tackle gender diversity, Avivah Wittenberg-Cox recently wrote on this site. Stop blaming women for what they do or don’t do, she argues, and train leaders to manage and develop a more balanced workforce. She makes a great point. Any cultural shift goes much more smoothly with the active involvement of the CEO and his or her (usually his) team. And it’s not realistic or fair to expect half the workforce to simply adapt their behavior to suit the other half, just because the latter are in charge.

But the evidence suggests that our leaders aren’t doing a very good job of it, at least not yet. Women still represent less than 5% of CEOs around the globe, and they remain seriously underrepresented in other top management positions and on executive boards. So yes, by all means managers should step up, but meanwhile, there’s no reason for an ambitious woman to sit on the sidelines and wait for her boss to get with the program. That’s what my colleague Lauren Ready concluded from a study she did here at the International Consortium for Executive Development Research, in which she interviewed 60 top female executives from around the world to learn how they rose to the top. Her aim was to uncover some lessons for the next generation, and she found that while each woman followed her own path, they had all taken charge of their careers in similar ways.

For one, these executives take the time to explore what they want out of work and life.

One byproduct of this effort is that they pay special attention to how they might fit within a company’s culture. This finding is consistent with research from HBS professor Boris Groysberg, who’s found that while the performance of male stars falters when they switch companies, women continue to excel, in part because they’ve done their homework when it comes to fit. The women in Ready’s study also understand the limits of fit. They aren’t “one of the guys” and they don’t try to be.

Another quality these women share is that they take responsibility for their choices—including the sacrifices they’re willing to make. “Male or female, there are no shortcuts to becoming a senior executive,” Ready writes. “The hours are long. The travel is exhausting. The stress is high. Let’s face it: Most of us would rather spend our weekends with family, not at 38,000 feet, in transit to our next meeting.” You can fight for better work-life balance when you get to the top (here’s one leader who quit business travel altogether), but you have to pay some dues along the way. The women Ready met with don’t point to a workaholic culture as a barrier. They either bite the bullet or walk out of the office at 5:00 with their heads held high. Many of those who leave early log on again once the kids are in bed, but some went onto a slower track for a few years and later ramped up. A few actually stayed on with a part-time schedule, even as senior executives.

Owning choices can require women to be vocal about their ambitions, so that other people’s preconceptions don’t get in the way. Mothers in particular may face assumptions about how much they can take on—they may be overlooked for projects that require long hours, for instance, or extra travel. One woman told Ready that she raised her hand for travel opportunities right after she came back from maternity leave. Another pointed out that nobody would presume that a male employee would need to be home at 6:00 to feed the children, but it was a notion that she had to preempt if she wanted to get her hands on a juicy assignment.

A third quality Ready observed in high-achieving women is the urge to bring other women along with them. Exceptional women leaders consider themselves stewards of the next generation. In their own journeys to the top, women’s programs or senior female role models were scarce. Now, having climbed the ranks, they are committed to helping rising female stars navigate their way. As one put it, “Senior-level women can see what’s coming. I call it being the career machete—to break down some of the barriers and prevent some of the slips and guide the person a little bit more effectively.”

This is not just a nice thing to do, Ready argues. These women view their stewardship as a way to raise their companies’ market value, by boosting the presence of women in senior roles and in boardrooms. With more women running the show, we should see more ownership of gender diversity through the ranks.

Get Your Virtual Team Off to a Fast Start

Whether you’re a virtual team leader or team member, there’s no honeymoon period anymore. The pressure to be productive from Day 1 is enormous.

We can certainly do a better job of on-boarding people to teams, especially when teams are not co-located. Too often on-boarding plans consist of a dozen or more documents that team members are supposed to read and digest on their own.

What’s missing at so many companies I work with is the time for virtual team members to learn from and form relationships with the people who are most important to doing their job successfully. And certainly no one should have to make sense of an organization in a vacuum. As a Harvard research team led by J. Richard Hackman found, seemingly disconnected threads of information make sense only when people have an opportunity to interact with others who can help them to contextualize the information.

What’s Your Relationship Action Plan?

I recommend that clients shorten the learning curve by helping every new hire put together a Relationship Action Plan. In it, list the 10-15 internal people who are most important to doing their job well and direct your new team member to build a relationship with each one in their first two weeks. Overwhelmingly, those who create a RAP report that it was the most useful thing they ever did in their first weeks on a project team or job.

My friend Ritesh Idnani, founder and CEO of a healthcare start-up Seamless Health, puts it this way: “You need to get people off to a flying start.” Ritesh gives each new executive two weeks to talk to each person identified in the plan as “important to know,” interviewing them about all aspects of the company and the job. Then he checks up, and finds the full-bandwidth effort over the new hire’s first few weeks pays off handsomely.

“At the end of two weeks I ask the person to sit down with me and tell me what he/she learned—their observations,” says Idnani. Not only do they have a new connection into the team: you renew yours. “You end up learning a lot from someone coming from the outside with a fresh pair of eyes.”

Planning a Great Team Kick-off Event

Newly-formed teams require more than a project plan and set of work streams to be high-performing.

Yet so often I see managers launch a team with a demotivating statement of the challenges the company faces coupled with a driving sense of urgency. The key to kick-starting a team is not to galvanize people into action through fear, but to ignite their desire to achieve both their own goals and the company’s. Although people do not come to work every day purely for the good of the corporation, their purposes often align. Whether it’s doing work that’s challenging and stimulating, working synergistically with a tight-knit team, or being associated with a good job in a well-known company–help people to understand that unifying driver.

In our work with clients, planning a great kick-off meeting is critical to developing a high-performing team. My advice to leaders for the kickoff is: don’t be afraid to show your vulnerability and humanity. It’s amazing how readily others respond when you allow people to see you with empathy. It opens employees’ porosity to the bigger message you’re trying to get across–the goals the team is trying to achieve.

Equally important is to structure a small-but-significant first challenge that will move everyone on the team toward the eventual goal. It has to be something that every team member can contribute to and has a hand in designing. And it needs to be something that can be achieved quickly, ideally within 60-90 days.

In our work with a major automaker, we quickly realized that the relationship between the company’s district managers (DMs) and its dealers was broken, limiting their ability to improve customer experience. So we challenged 300 DMs to choose a single dealer and turn the relationship around. The results exceeded even our expectations:

Highest JD Powers owner-satisfaction ratings of any American car company

Customer satisfaction index (CSI) scores more than doubled to 100% in eight out of 10 surveys

Market share shifts in pilot regions

Another important part of launching a new team is getting team members to do something together that unleashes collaboration and innovation. A number of successful executives I know swear by going with something that merely puts everyone at ease. For example, building the tallest tower possible using only stationary supplies (no fasteners). Even I have to admit it’s fun and inspiring when a virtual team takes on the tower-building task connected only by video software.

Keeping the Momentum Going

A great virtual team launch has the potential to motivate members to deliver their best, but more is required. A study by OnPoint Consulting showed that excellent communication from the leader is a strong predictor of team performance. Anthropological studies show we’re not the only primates that rely heavily on such communication: baboons, chimpanzees and gorillas glance at the dominant male every 20-30 seconds on average for cues.

Unfortunately, senior managers frequently assume that sending email updates and holding weekly conference calls is enough to sustain the momentum generated by a kickoff. It’s not. In the absence of visual and body language signals, misinterpretations and misunderstandings often arise. Team members feel disconnected and reduce the level of engagement and contribution to the project.

Here’s where leveraging technology can be a huge asset. I know of one company that uses an always-on, wall-sized video screen to stay in touch in with team members in Beijing, building relationships virtually and increasing the frequency of collaboration.

Another important way to keep a virtual team focused on its goals is to celebrate small wins along the way. Dan Ariely, professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University, has shown that public recognition is far more important than financial incentives in the workplace. Despite this, many managers do a poor job of recognizing their people. I’m sometimes amazed by how difficult it is to persuade some executives of the importance of publicly celebrating an employee who exemplifies the behaviors senior management wants to cascade throughout the organization.

Whether you’re on-boarding new executives or launching a newly-formed virtual team, people need the time and the permission to develop relationships. While it may sound more cost-effective to rely on collections of reading material and org charts to get people up to speed, their understanding both of the project and the company’s goals will suffer, decreasing their effectiveness.

Children’s Feelings About Brands Persist into Adulthood

Consumer-brand companies’ investments in child-oriented advertising provide brand benefits long after the audience has grown up, says a team led by Paul M. Connell of the State University of New York at Stony Brook. For example, people in the UK who had been exposed to the Kellogg’s Frosties character Tony the Tiger as children and the Cocoa Pops character Coco the Monkey as adults rated Frosties as more healthful than Cocoa Pops (3.84 versus 3.24 on a 7–point scale), suggesting that the participants retained warm feelings about Tony from childhood. The findings raise concerns about child-oriented ad campaigns for products with potentially adverse health consequences, the researchers say.

How to Improve Yelp’s Top 100 Restaurant Rankings

Last month Yelp unveiled its list of its Top 100 Places to Eat in the U.S., and an unlikely restaurant claimed the top spot: Da Poke Shack, a local Hawaiian Ahi Poke place with average prices under $10. Alinea, perhaps the flagship haute cuisine restaurant in Chicago with a much higher price tag, was ranked #7.

The rankings caused a debate between the two of us: Could this list possibly be right?

As it happens, one of us (Eddie) was born and raised in Hawaii, and he’d just eaten at Da Poke Shack last summer. He agrees with the ranking.

But we both live in Chicago, and the other of us (Jim) insists the data is overwhelmingly in favor of Alinea, a Michelin three-star restaurant with widespread critical acclaim.

The reality is that context is king. Different consumers, seeking different benefits, for different need states rated Da Poke Shack and Alinea very high. And for the distinct jobs those restaurants were hired for, Da Poke Shack did a wee bit better. The missing ingredients to make online reviews really relevant is not more algorithms and super computers, but adding anthropology and Super Consumers.

Yelp is a go to app many people, but we want sortable online reviews by consumer context. Trip Advisor does this nicely with their hotel filters by business vs. leisure vs. family. For e-commerce, we wish we could sort reviews by Super Consumers—high passion and high profit consumers. Wouldn’t you weigh the reviews of someone who read 200 books last year higher than someone who read 2? For Chinese restaurant reviews, wouldn’t you want to see the reviews by folks who grew up with authentic Chinese food vs. folks who like the Americanized version?

The issue with online reviews is a broader one, as many companies have an approach to growth and innovation that is technology for technology sake, with little regard to the consumer context or emerging or latent demand. And the risk in missing the consumer context is huge. In mobile phones, was the right consumer context making calls from Antarctica or being able to play Angry Birds? The difference was losing billions with Iridium versus making hundreds of billions with the iPhone. Who would have guessed that one of the most successful commercial applications of nanotechnology would be wrinkle-free, stain-resistant khakis? Part of the initial success of energy drinks was the consumer context in bars and mixed drinks. Olestra was not successful as it anchored itself in snack foods, where consuming too much Olestra had some unpleasant side effects.

There are a few ways to fix this. First, you have to acknowledge the importance of the consumer context and start a dialogue with Super Consumers to understand it. Second, capture better consumer context data with the reviews themselves. You can do it prospectively with new reviews by allowing consumers to add context when writing reviews. You can do it retroactively by using key word search for distinct benefits (e.g., great price, awesome selection, delicious and tasty, healthy and fresh) in past reviews to identify what benefits matter. You can also fuse review data with big data on consumer spending from sources like the Nielsen Homescan panel or Prizm. Finally, create sortable tools to allow consumers to pick the reviews that are most helpful to them (e.g., Supers vs. Casual users, filtering for folks who rated the same two brands for the best heads up comparison). Those who get this right will ultimately change traffic to review sites, as precision will become more important than scale.

Our belief is that empathy and emotion found in the right consumer context is perhaps the single biggest under-utilized lever for success in Silicon Valley. We hope more companies will embrace consumer context, as we are eagerly awaiting online reviews 2.0.

But until then, we have proof that that an $8 Ahi meal outdid Alinea, that a fresh fish rice bowl surpassed French Laundry and Poke trumps Per Se.

March 17, 2014

The Future of Prototyping Is Now Live

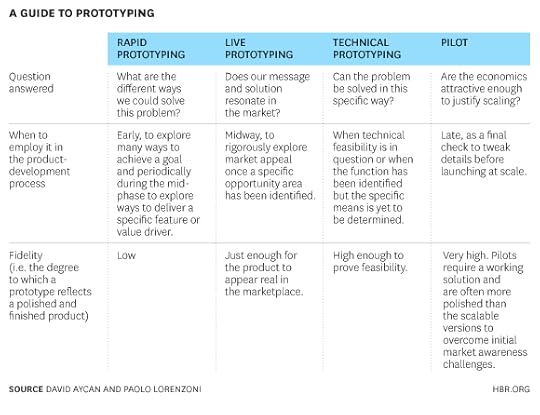

Those tasked with developing new products and experiences have long valued prototyping as a way to fuel creativity, explore options, and test assumptions. By making concepts real, we can more intimately understand the underlying mechanics and make informed judgments. There are two main ways that organizations prototype new products and services: rapid prototyping and piloting. However, we’ve discovered the need for an approach that falls somewhere between the two—to explore the customer value proposition and market appeal of a concept in the more turbulent and distracting context of the live market, but without full investment in a pilot. We call this approach “live prototyping.”

To better understand the value of live prototyping, it’s helpful to put it in the context of the two dominant types of prototyping. Rapid prototyping aims for quantity over quality. Dozens of sketches, wireframes, enacted service scenarios, and Play-Doh models are created quickly to get a feel for ideas. On the other end of the spectrum are pilots and technical prototypes, which generally aim to get as close to the “right” answer as possible and therefore cut few corners in delivering on the full experience. Pilots are used to prove economic viability, while technical prototypes are sometimes built to prove technical feasibility and to evaluate the merits of different technical approaches. They require a high degree of investment and are expected to be very close to the final version, because they’re generally precursors to launching at scale.

Live prototyping replaces techniques like surveys, bases testing, and focus groups. It involves releasing still-rough concepts into the context where consumers would eventually encounter them during the course of their daily routines—for example, on a store shelf, at a hotel check-in counter, or in an app store—with all the associated distractions and competing choices. Like all good market research, live prototyping is ideally both qualitative and quantitative in nature. We start by observing behavior naturally unfold before conducting intercepts and interviews with consumers to probe deeper. We also make sure to have enough consumer engagement to observe quantitative patterns with pre-selected metrics.

The table below explains where live prototyping lies within the process of bringing an idea to market.

We’ve used live prototyping in a variety of contexts and industries. We’ve used it to explore new brands for major food and beverage companies and start-ups like Koudai, an internet retailer in China; to gauge customer interest in workplace solutions for Steelcase; to test the waters for enterprise software packages for Salesforce; and even to explore ways to engage the live crowds at the “TODAY” show.

Of course, live prototyping has advantages and disadvantages, which you should understand before you add it to your product-development toolkit. Among its advantages, live prototyping:

Conserves capital: By “cutting corners” relative to a full pilot, we can evaluate market appeal without the capital investment that a pilot requires. Usually, we can do several iterations of live prototyping for the price of a single pilot.

Considers context: Since live prototyping occurs in context, it helps generate an understanding of how environmental and situational factors affect the appeal or visibility of a solution. In this way, live prototyping allows us to observe what people do, not just what they say they’ll do.

Improves forecasting: Forecasting sales for new-to-the-world solutions is exceedingly difficult and predicting consumer uptake is often the most arbitrary part of the exercise. Seeing a solution succeed next to the competition, before it is formally launched can make forecasting much less of a guessing game.

Provides qualitative and quantitative feedback: Live prototyping allows us to capture many different types of feedback, including consumer behavior data, rich qualitative observations and insights from consumer interviews, which help us unpack choices and behavior. Taken in aggregate, this basket of feedback allows us to better iterate our solutions.

Live prototyping has three main areas of disadvantage:

Longitudinal feedback: Since live prototyping usually addresses the resonance of a value proposition in context, we generally invest more on the fidelity of initial packaging and associated marketing materials, and less on the features that deliver value over time. Hence, it is usually more difficult to use live prototyping to evaluate retention and engagement over time. While we have done this in the past, the effort to do so gets close to that of a pilot, and so the speed benefits of live prototyping are not as easily realized.

Exploring broad options: Since it takes significant effort to build a channel-specific solution during live prototyping—arranging testing locations, building displays, for example—it can be challenging to explore a diverse set of concepts. For example, live prototyping can work well to test a number of different food brand options, even across different retailers, but if some concepts require completely different channels, for example vending machines, then the process becomes unwieldy.

Cultural norms: While American consumers have shown a hunger to co-create solutions with companies and tend to celebrate brands that embrace experimentation and that are “always in beta”, this is not always true in global markets. It’s important to calibrate what degree of “roughness” is going to be acceptable based on the market in which you’re operating.

Consistently using live prototyping as part of a product-development process helps negate risks associated with the messiness and unpredictability of the market. For example, it reduces the chances of getting blindsided because people behave differently than they stated they would in a survey, or that a product that popped in a focus group gets lost in the retail environment, or that a new value proposition was just a bit too complex for consumers to learn about on a busy shopping trip. Ultimately, by testing more ideas in market, with lower investment, and only piloting the most promising ideas, a company can radically improve its return on invested capital for new products and experiences.

Can Design Save Silicon Valley?

The tech titans of Silicon Valley are actively circling the strategic value of design. I didn’t take their interest seriously until I saw the news in December that John Maeda, the former President of the Rhode Island School of Design, joined venerable VC firm Kleiner Perkins. He’s the Valley’s first-ever Design Partner. That’s a serious step into the mover-shaker circle for the design profession.

The reasons for an investor focus on design are not all that hard to understand. “Great design” has helped drive Apple’s valuation to $475 billion, while AirBnB, Square and Pinterest all demonstrate how superb user experience design attracts both rabid fans and VC investment (over $1 billion between them, to date). Last, but far from least, is Google’s $3.2 Billion acquisition of the design-centric Nest, maker of a smart thermostat.

Appreciation for design in the tech world didn’t come overnight; it has been on the rise for some time. As the first industrial designer to graduate from Harvard Business School, I thought design had hit the big time a few years ago, when the students at my alma mater created a Design club. By contrast, when I was an MBA there our case studies (and those at every b-school) presented new products as originating from some kind of immaculate conception. Design was not an actor in the business dramas we studied. The school’s appreciation for design’s strategic importance has come a long, long way since those days.

But when I hit the road in 2008 raising capital for our fairly design-centric venture, The Grommet, I noticed that no investor ever remarked on my industrial design credentials. Venture capitalists were far more accustomed to the expertise of a software developer or even a mechanical engineer than to a person who could create the overarching user experience. This lack of familiarity with design was bizarre, but also deeply familiar to me. When I first told my own father the name of my college major, he thought that industrial design meant creating factories.

While I long ago stopped worrying about when design would be invited to sit at the grownups’ table, I couldn’t help but be excited by the news that Maeda was joining Kleiner Perkins. He has blogged about his early observations at Kleiner, arguing for design’s potential in the tech world:

The marginal excitement generated by more memory or faster processor speeds has lost its allure in recent years because there’s generally enough computing horsepower to do everything we might want to do. So we don’t yearn for the bigger, brighter or even cheaper as much anymore. We now choose based upon design – the answer to “how it feels” versus “how fast it is.”

I reached out to Maeda to ask about how he was finding the position, and he responded that in week four on the job he had given an hour-long presentation on design and tech to all of Kleiner’s partners. “Given the strong, positive response after my presentation, it’s clear that there’s a there-there,” he wrote.

I’m sure I speak for design-oriented entrepreneurs everywhere when I say that it’s about time.

In Search of a Less Sexist Hiring Process

The hard truth is that the gender balance at the top of the business world won’t change until the gentlemen currently in power want it to — and learn how to do it. The challenge is that both men and women seem to buy into the mistaken notion that business today is built on meritocracy. A recent study by three business school professors illustrates why this is so rarely true.

Several managers were asked to recruit people to run some mathematical tasks. The talent offered to them was an equal mix of men and women, with equivalent skills. The researchers found four things that exactly echo what I have seen in countless companies:

• Male and female managers were twice as likely to recruit men, based on paper applications.

• When interviewed, the male candidates inflated their abilities while the women downplayed theirs. But recruiting managers failed to compensate for that difference, and were still twice as likely to choose the man.

• Even when provided with data that the women were just as capable, the managers still preferred men (who were 1.5 times as likely to be hired).

• When managers knowingly chose a candidate who had performed worse on the test, they were two-thirds more likely to choose a male candidate.

Until hiring and promotion practices change, women can “lean in” all they like, graduate in record numbers from top universities, and dominate buying decisions — but they still are much less likely to make it to the top. The corporate world is led by men confident that they are identifying talent objectively and effectively. The reality, underlined by this and many other reports, is that decision-making about talent is rife with unconscious assumptions and personal biases.

Leaders are routinely identified based on perceived ambition, self-confidence and charisma. Yet they are doing little more than self-replicating a masculine, Anglo-Saxon management style that may have outlived its utility in today’s highly complex, global and multi-cultural business world. Consider: Ambition is usually laced with hubris (hasn’t the financial crisis taught us this?). Self-confidence is a poor proxy for competence. And charisma is often a polite way of saying “loud” and “dominant” – something many of our Asian colleagues are happy to quietly point out.

In Western companies, a preference for a masculine style of leadership is deeply ingrained, largely unconscious and reliably self-reinforcing. The only hope of overcoming anything unconscious is to make it conscious. So self-awareness and understanding is the key challenge for any organization that really wants to change its very human and natural preference to reproduce itself in its own image. This is just as true for shifting away from the dominance of any group in power – whether it’s all men, all engineers or all people born in the home country of your corporate headquarters.

This kind of change takes leadership, and lots of it. This requires a number of steps, mostly to do with getting the majority in power to be responsible and accountable for leading the change. They are the only ones that can do it. Expecting women to be responsible for gender balancing organizations — either by setting up a corporate “women’s network” or asking them to try harder — is a set-up-to-fail design error. Instead, corporations need to take several steps to redesign how they’re hiring and promoting talent. I discuss this in detail in my latest book, Seven Steps to Leading a Gender Balanced Business, but here is the short version of the steps that apply to hiring:

• Reframe the issue so that it is seen as a business issue and not a women’s issue. If managers are choosing less qualified men over more qualified women, the company is clearly losing valuable talent. Even if hiring managers are choosing equally qualified men, if they’re doing it in dramatically greater numbers (as the study above shows they do), the company is still missing an opportunity to build the kind of balanced workforce that we know produces more creative results.

• Build the skills of the majority, rather than the minority. Most companies spend more effort “fixing” women than on educating managers. You can expect all your women to suddenly change their behavior and start over-selling their skills, as the men in the study above did — but frankly, do you really want them to? Research also shows that when they do, they are judged negatively for it. Instead, get leaders to understand their own unconscious preferences in gender issues and learn how to achieve the balance they say they want. Educate all managers – both male and female – using studies like this one to make sure they understand well-researched behavioral differences between genders and can manage effectively across them.

• Get hiring systems to match. The biases shown in the above study are also at work within many systemic HR processes. For instance, it’s common practice in large companies to have “ambition” be an explicit criteria for leadership. Many studies have shown that men tend to over-promote themselves and women tend to do the contrary. So leadership selection and assessment panels (that are often neither gender balanced nor gender aware) naturally give preference to the classic existing profile, convinced that they are objectively evaluating the “best.” This does not make room to develop the majority of today’s talent for tomorrow’s world. Nor allow a variety of leadership styles to co-exist.

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting the same result. Companies that continue to use biased talent management systems — unwittingly or not — will continue to get exactly the same results. Equally competent women will learn from the system that others are considered better – and believe it. “People don’t even learn that they are equally capable,” as one of the study’s coauthors, Luigi Zingales of the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, told the New York Times. Research pointing to women’s supposed “lack of self-confidence” overlooks this point: Men and women are born with similar ambitions, talents and ideas. Then we teach them bias.

Companies get the women – and leaders – they design. Ignoring our biases simply lets the dominant group continue to dominate. The only way out is embracing our unconscious judgements. Learn to lead, and don’t let your bias get the better of your talent.

Give Impact Investing Time and Space to Develop

Impact investing has captured the world’s imagination. Just six years after the Rockefeller Foundation coined the term, the sector is booming. An estimated 250 funds are actively raising capital in a market that the Global Impact Investing Network estimates at $25 billion. Giving Pledge members described impact investing as the “hottest topic” at their May 2012 meeting, and Prime Minister David Cameron extolled the potential of the sector at the most recent G8 summit. Sir Ronald Cohen and HBS Professor William A. Sahlman describe impact investing as the new venture capital, implying that it will, in the next 5 to 10 years, make its way into mainstream financial portfolios, unlocking billions or trillions of dollars in new capital.

As this sector moves from the margins to the mainstream, it’s important to consider: What will it take for impact investing to reach its full potential? This question is hard to answer because, in the midst of all of this excitement, there aren’t clear success markers for the sector. Without those, the institutions managing the billions of sector dollars won’t be able accurately to assess the risks they are taking and, more important, the returns, both financial and social, they hope to generate.

Impact investing is not just a new, undiscovered corner of the investing world. It has the potential to join traditional investing and government aid and philanthropy as a third way to deploy capital to address social and environmental issues. A fully developed impact investing sector will incorporate the best features of markets—rigor and speed; quickly evolving business models; strong revenue models; and access to capital as ventures show signs of success—with the best features of government aid and philanthropy—serving unmet needs; reaching populations that are bypassed or exploited by the markets; investing in goods with positive externalities; and leveraging public subsidy to extend the reach of an intervention—to solve social problems.

Because impact investing really is something new, the old ways of assessing risk and return are not enough. And yet, like a moth to a flame, those in the sector are endlessly drawn to discussions around what constitutes the “right” level of expected financial returns. There is no single right answer to this question. Under the broad umbrella of impact investments lie myriad sectors, asset types, and investment products, most of which still need to be developed and understood. It looks something like this:

Impact Investing in 2014 : Colorful, full of potential, and highly disorganized

Note: Each circle represents a business and each color represents a business vertical (e.g. sanitation, housing, mobile banking).

To make sense of this kaleidoscope, three things need to happen.

First, impact investing needs time to develop. This is a nascent sector where entrepreneurs and investors are still figuring out business models, developing new financial products, and proving exit strategies and exit multiples, and only a handful of players are using agreed-upon metrics for assessing social impact. Whether it’s solar lighting, mobile authentication, micro-insurance, mobile banking, drinking water, urban sanitation, low-income housing or primary health care, entrepreneurs need time to test, modify, and refine business models. These entrepreneurs are looking for support from risk-seeking investors who have an appetite for failure, are willing to be pioneers, and who value the social returns they’re creating.

As the sector grows through this period of creative destruction, models that don’t work will die out, models that survive will attract copycats, operating costs will go down, and winners will rise to the top. The sector will organize itself across the spectrum from philanthropy to investing, and the resulting clusters will demonstrate the differences in risk, financial returns, target customer, and social impact across the various sub-sectors of impact investing.

Impact Investing in the Future: Developed clusters across the spectrum

Second, in addition to time, the sector needs a framework to measure success, one that makes sense of the sector’s inherent diversity. Akin to the Morningstar Style Box, such a framework would allow an investor to easily identify best-in-class social and financial performance across and within the various sub-sectors of impact investing.

Third, the sector needs practical, widely-adopted, and standardized tools to measure social impact. This is easier to describe than it is to do. Although investors value both financial and social return today, the sector only measures financial return well. The big, unspoken risk is that we’ll end up ranking and sorting impact funds by the only thing they can be ranked and sorted by – money – without assessing or valuing the different levels of social impact these funds have.

The future of impact investing depends on our ability to embrace what we’ve learned over the course of economic history: solving social issues requires both private and public capital, a combination of risk-seeking investors and incentives and subsidies from public actors to make it easier and more attractive to reach underserved segments of the population. Hospitals, parks, educational systems, sanitation infrastructure, low-income housing — globally, risk-seeking investors build these solutions in partnership with the public sector, which plays its part to adjust incentives, act as a major customer, and provide subsidy where needed.

What the sector needs is enthusiasm about the future and patience around the time it will take to get there. In traditional investing there is a premium on liquidity, low beta, and lower risk, all of which justify higher or lower returns. In impact investing, we need to find a way to place that same premium on social impact by valuing the public good being created – just like we do in early stage R&D in science, IT, health, and biotechnology. We allowed microfinance and the venture capital industry the time and space to develop over a few decades. Surely we can do the same for impact investing.

A Presentation Isn’t Always the Right Way to Communicate

We rarely think about whether presentations are the best way to express our ideas; we just blindly create and deliver them. By some estimates, 350 presentations, on average, are delivered every second of every day.

Unfortunately, presentations can’t be the Swiss Army knife of communication. Though they’re one of the most powerful tools we have for moving an audience, even the most carefully crafted talks won’t be effective if they’re not delivered in the right context. Sometimes, a conversation is much more appropriate and effective.

How do you know when that’s the case? Ask yourself what you want to get out of the time you have with the group. Do you need to simultaneously inform, entertain, and persuade your audience to adopt a line of thinking or to take action? Or do you need to gather more information, have a discussion, or drive the group toward consensus to get to your desired next step? Generally, if your idea would be best served by more interaction with your audience, you should probably have a conversation instead of delivering a presentation.

The best conversations will happen when you’ve briefed everyone ahead of time on the information you’re going to discuss. (Otherwise, you waste valuable meeting time playing catch-up instead of working toward your goal.) To get everyone up to speed, create a visual document in presentation software — what I call a slidedoc – and circulate it before the meeting.

Of course, it’s common practice to circulate decks of slides before meetings, but often they’re too opaque to be understood without guidance from a presenter — or they’re so packed with “teleprompter” text that people have a hard time digesting them. Asking everyone to decode your cryptic bullets or plow through a lot of verbiage before you meet is setting yourself up for disappointment. Nobody has the time, and your ideas could get lost in translation. So give people a document that’s meant to be read, not presented. One they’ll grasp quickly and easily on their own.

You can create a slidedoc by re-chunking your message into key points and illustrating them with pictures or diagrams, along these lines:

Studies show that this combination — concise text paired with visuals — helps people understand and retain concepts more easily. As clinical psychologist and author Haig Kouyoumdjian points out, “Our brain is mainly an image processor (much of our sensory cortex is devoted to vision), not a word processor. In fact, the part of the brain used to process words is quite small in comparison to the part that processes visual images.” So, pare down the wording, but leave enough context to allow your deck to live on its own without your voiceover.

Slidedocs can serve not only as prereading for conversations but also as emissaries and follow-up material. For example, when people in positions of influence say, “Send me your slides,” before they’ll book a meeting with you, you can e-mail them a slidedoc with all the relevant information. Slidedocs can also outline what people can do to give your idea traction after you’ve sold them on its value in a presentation.

But why use presentation software for these types of communication? Because it allows you to create modular content that’s easy to share, and it’s much easier for the layperson to use when combining visuals and prose than, say, professional design software. For both reasons, it will extend the reach of your ideas — which is, after all, the point.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers