Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1453

March 17, 2014

When Women Take Over Family Firms, Profitability Increases

A study of thousands of family-owned firms in Italy reveals that, on average, replacing a male CEO with a woman improves a company’s profitability, an effect that becomes more pronounced as the proportion of women on the board of directors increases, says a team led by Mario Daniele Amore of Bocconi University in Milan. Overall, the more women on the board of a female-led firm, the more profitable it is likely to be. The presence of women directors may make female CEOs feel more comfortable, improving cooperation and facilitating information exchange, the researchers say.

How Companies Can Attract the Best College Talent

Over the past year, my firm Collegefeed met with more than 300 companies to understand their college hiring strategies and tactics — from employers with large university hiring infrastructures to recently funded start-ups looking to hire fresh grads, interns, and young alum.

Not surprisingly, 84% understand that college hiring is important. Yet almost all agree that it’s really hard to attract good college talent. In fact, 92% believe they have a “brand problem” when it comes to their efforts; this problem is often expressed as the fact that “not everyone can be an employer like Facebook.” In other words, large, well-established companies feel they simply can’t be the newest thing out there generating buzz with Millennials.

To understand more about this underlying “brand problem,” and what employers can do about it, we polled 15,000 Millennials — 60 percent still in college and 40 percent recent graduates.* We asked them:

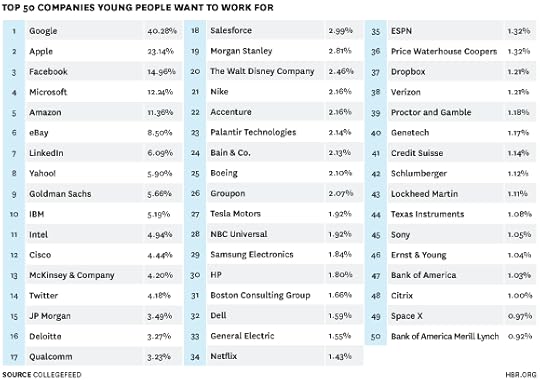

What are the top three companies you want to work for?

What are the top three things you look for when considering an employer?

How do you generally discover companies and create an impression about them (social media, product usage, campus events, other ways)?

Here’s how they responded:

Question 1:

Respondents had to type in and enter a name here, not select from a displayed list, which eliminates the pagination bias. That said, the top 10 in this list are not surprising at all: They are well-known brands that frequently appear in the “best places to work” lists.

But what’s noteworthy is the absence of well-known consumer brands such as Coca Cola. It’s also interesting that companies like Salesforce.com and Qualcomm, which most college students don’t use, appear so high.

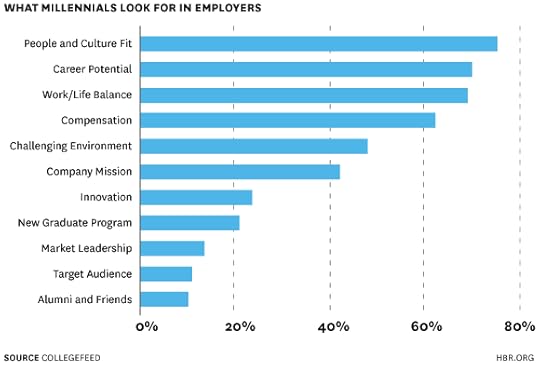

Question 2:

Given the first chart, you might expect things like “company mission” or “market leadership” to be on top. However “people and culture fit” is number one, followed by “career potential.” We expected “compensation” to be within the top five, but were somewhat surprised that it was only ranked fourth.

This data leaves one key takeaway: It is imperative to focus on communicating your culture and career growth to potential employees. The two fundamental questions that young job seekers ask, and that companies need to answer are: “What is it like to work there?” and “What kind of growth can I expect?”

Question 3:

These results blew us away. Most companies (almost 100% of the large ones we spoke to) say that they have an on-campus recruiting plan and that is where they focus their sourcing and branding efforts. Many also have dedicated organizations to build relationships on campus. According to a 2013 NACE study, 98.1% of companies they polled believe that on-campus fairs are the number one avenue for them to brand themselves with students.

However, this may not be the case. “Friends” showed up as the number one way Millennials hear about companies, according to our research, followed by job boards. You might also expect to see “Use their products every day” among the top five, but it showed up sixth.

Clearly, branding — how a company is perceived year round, across media types — is more important than just being present on campus. If college students like something, they tell their friends on social media or face-to-face.

So whether you sell ads, insurance, food, or routers, building a brand among college grads is about getting your story out. Sure, some companies have the basic advantage of “being among the top products students use daily” or “building the next big mobile app,” but you can also attract great talent by telling your story right – using language that Millennials relate to at places they frequent.

Here are the four most critical things you should do to improve your brand and attract the best college talent:

1. Get Your Best People to Engage With Students

Even if you are a company whose products never really get used directly by end users (think Salesforce.com, Qualcomm, Ciena, Cisco) you can still show off your employees and organizational culture to send a simple but powerful message to students: “If you come work for us, you will get to work with awesome people like these.”

So if you go to campus, bring your best recent college hires along. Showcase the work interns, young alums, and others have done, and highlight the responsibilities they have been given. If scheduling the best people or alums is hard, or if you find the attendance of physical events is low, host virtual info sessions, another easy and scalable way to reach lots of great college talent.

In addition, some leading companies we spoke to set quarterly goals for managers to hire and spend time with potential hires from colleges, whether it’s attending career fairs or answering questions on Quora or blogging about their experiences. And this leads to another important thing you can do to attract college talent.

2. Go Where Students Are (and They’re Often Not at College Fairs)

Students are online all the time. Invest in a visually appealing, content rich site where students can go to and learn about your company. If you can, personalize the site to showcase the right alums, intern experiences, and the basic messages you want to deliver to potential hires. Done right, a good “brand page” can have the same effect as a great conversation at a career fair — it’s the story of your mission, your culture and why they should join you.

Next, use social media smartly. College students spend two to four hours daily on sites like Facebook and Twitter. If you can target them based on specific interests, who they follow, and what they are searching for or talking about, real-time engagement can be quite powerful. Depending on the type of talent you are targeting, sites like Quora and other more technical ones like Hacker News can be good places to establish your brand. Similarly, if targeting a broader audience, you can go far by using humor to engage students in entertainment properties like Reddit, BuzzFeed, and CollegeHumor — people share what they find funny.

One caveat across social media in general: most online communities don’t like being marketed to, so be authentic, add value to users, and be cautious of blatant self-promotion.

3. Make the Application Process Easy and Engaging

A complicated, multiple-page application form isn’t going to cut it anymore. For Millennials (and anyone else, really), the process should be easy and frictionless.

In addition, you can’t always wait for students to come to you. After connecting with a student at a career fair or online, it’s important to go back to them and encourage them to apply when they are ready.

Another engagement strategy leading companies have found is to pique student’s interests by holding online contests and activities that paint an interesting picture of their brand. Google, Microsoft and several other companies do this programmatically.

4. Prioritize Meaning Over Swag

Too many companies are focused on giving away swag, under the perception that free stuff gets eyeballs. But Millennials are more interested in identifying with your mission than they are in a free T-shirt. If you want their mindshare you have to go beyond swag, and that concept should extend beyond career fairs to everything they read and hear about you.

Are you securing people’s futures? Are you making the world green? Are you making life simpler for small and medium businesses? Whatever you do, you should be able to get the message out online — in a 20 or 30 second video. The U.S. Army’s age-old recruiting video is still a great example – it really makes you want to apply.

If you get meaning right, it won’t just be you doing the talking. Social referrals have incredible power in the college context, and we’re not talking about the “refer a friend, get $5” model. It comes down to whether a student genuinely likes who you are, what you do, and what you stand for.

*Of the responses received, 65 percent are in college and 35 percent recently graduated. 60 percent were male and 40 percent female. 50 percent were tech-oriented majors and 50 percent non-tech.

March 14, 2014

Two Ways to Reduce “Hurry Up and Wait” Syndrome

Have you ever been asked to drop everything to complete a seemingly urgent task, and then found that the task wasn’t so urgent after all?

Not long ago, one of our clients gave us three days to put together a proposal to help with a very large and complex reorganization. Although we had been talking about the possibility of working on this project for months, the client suddenly felt that it was time to get started. We didn’t want to miss the opportunity, so we put in some late nights and did what was needed to craft a reasonably good document. And then we waited.

Two weeks later, the client sent a note saying that she hadn’t yet had time to read the proposal but would get to it soon. And in the meantime, she was still trying to secure agreement on the reorganization with her boss and other key corporate function heads.

Obviously, something doesn’t add up with this picture. Why did the client give us only three days and convey such a sense of urgency if she wasn’t really ready to move forward? Was she being dishonest or was she deluding herself about the situation — or was something else going on?

Having seen many variations on this “hurry up and wait” dynamic over the past few years let me suggest a possible explanation. I’ll also offer some ideas about what to do if you are falling into this trap, whether it’s as the perpetrator or the victim.

The starting point for understanding this issue is the dramatic acceleration of today’s business culture. Because we live in a world of continual, real-time communication from anywhere in the world, we’ve gotten used to assuming that everything happens instantaneously. As such, it’s almost unthinkable for managers today to give an assignment (whether to a consultant or subordinate) and say, “take your time” or “think about what it will take and let me know when you can get to it.” Instead, the almost unconscious default position is to push for rapid action.

Intersecting with this drive for speed is the reality that many organizations have slimmed down over the last few years. But while they have reduced costs and taken out layers of managers and staff, they often haven’t eliminated the work that those people were doing. So the surviving managers are expected to do more and more, and do it faster and faster.

The result of trying to drive more work through fewer people, and at greater speed, is a jamming of the queue. There is simply no way to get everything done in the accelerated time frames that many managers expect. So while their intentions are to move quickly on things, the reality is that you can only force so much work through the eye of the needle.

The problem is that some tasks or assignments really do need to be carried out quickly. But unless they are treated differently, they get caught up in the same bottleneck with everything else. It’s like the common phenomenon that happens in hospital laboratories: Doctors want test results from their patients to be done right away, so they label them as “stat” (which means “immediate”). When the lab gets too many stat requests however, everything is treated the same, which means that nothing is done immediately.

In our case, the manager really did want to move quickly with the reorganization. But then she was inundated with other tasks, requests, meetings, and priorities and had trouble finding the time to read our proposal. She also thought that she could get her boss and other executives aligned on the reorganization, but couldn’t find the time to get them all together, or even meet with many of them one-on-one. So while she genuinely intended rapid action, she just couldn’t pull it off.

Obviously there is no easy solution for dealing with “hurry up and wait” syndrome. But if you feel that this dynamic is affecting your team’s work, here are two suggestions:

First, put a premium on eliminating unnecessary or low value work. Are there repetitive activities that your team is doing that don’t make a difference, or could be done less often or with less effort? One overloaded manager, for example, got permission from her boss to report her team’s activities on a monthly, instead of weekly, basis. That change gave her team more bandwidth to handle urgent projects.

Second, inject more discipline into the prioritization of projects and tasks. Work with your team to identify those few things (and not more than a few) that really do need to be done with speed. And when a new request comes in, make explicit decisions about where it fits in the list of priorities – and if necessary, challenge the assumption that it needs to be done right away.

Given the desire for speed that permeates today’s business culture, we’ll all probably experience hurry up and wait syndrome at one time or another. If we can do a better job of prioritizing, however, we might face it less often.

Could Target Have Prevented Its Security Breach?

Less than a year before the Thanksgiving security breach in which credit-card info for 40 million shoppers was stolen en masse, Target bumped up its security staff and brought in software from a top-notch firm, FireEye, whose customers include intelligence operations worldwide. FireEye’s sophisticated system worked: It triggered alerts that malware had entered Target’s computers. Because the attack was spotted early, the whole mess could have been avoided.

Except no one did anything. FireEye's automatic malware-deletion function wasn't enabled (which isn't uncommon, as many organizations want a person, rather than a machine, making the decisions), and the alerts were ignored. There may have been some skepticism about the system, because it was new to Target. In any case, the inaction allowed what's described as "absolutely unsophisticated and uninteresting" malicious code to wreak havoc on the company's reputation and customers' lives. In attempting to trace credit-card hackers and brokers throughout the world, the article's authors hint that this particular breach and others like it are likely far from over.

In response, Target acknowledged that its computer system had been alerted to suspicious activity. According to a spokesperson, "With the benefit of hindsight, we are investigating whether, if different judgments had been made, the outcome may have been different."

Ackman v. Herbalife After Big Bet, Hedge Fund Pulls the Levers of PowerThe New York Times

If you’re looking for the corporate-governance version of House of Cards, this is probably the closest you'll get (though there's no strategic murdering here, as far as I know). This breathtaking investigation into activist investor William Ackman's $1 billion bet against Herbalife has all the elements of a good drama: It pits the dietary-supplements company against the larger-than-life Ackman, who has said that he will "personally pursue the Herbalife matter to the end of the Earth." The pursuit has thus far entangled members of the government and community groups, cost huge amounts of money, and enlisted more lobbying firms that you can count (working tirelessly for both Herbalife and Ackman). The investor is famously patient; one of his biggest wins came after a seven-year battle. And while he steadfastly claims that Herbalife is a hugely damaging pyramid scheme, the only real certainty in his war is that he has the power, money, and determination to do whatever he wants, often without people knowing he's doing it.

Watch Your MouthSheryl Sandberg and Anna Maria Chávez on 'Bossy,' the Other B-wordThe Wall Street Journal

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and her Lean In organization want to ban the word "bossy" when it's used to describe assertive girls and women. Sandberg and Girl Scouts of the USA CEO Anna Maria Chávez outline why the word needs eradication, pointing to its historically gendered use to put down and socially alienate girls. The duo explains that males are rarely described as bossy when they push to lead. They ask, "How are we supposed to level the playing field for girls and women if we discourage the very traits that get them there?"

Predictably, everyone has something to say about the "B" word. Sally Kohn tackles the issue from a parenting angle. Sayu Bhojwani argues that everyone, including men, should stop talking so much in the first place. Others, like Jessica Roy and Ann Friedman, smartly drill down into the interplay between feminism and semantics. As Friedman explains, "It’s so frustrating to watch Lean In try to expand girls’ options by restricting the way we talk about them. It’s counterintuitive, and it makes feminists look like thought police rather than the expansive forward-thinkers we really are." But the outpouring of opinions, argues Jena McGregor, may be a good thing: "As long as the argument persists about how to get more women at the top, it remains on everyone's minds — and hopefully, on more people's agendas."

What Really Goes Into Your Latte Inside The Barista ClassThe Awl

At a time when it seems as though everyone is down on retail and service work (see this recent piece, for example), Molly Osberg's essay on being a barista is refreshing not only because it places a more positive lens on type of employment — "serving can be deeply satisfying work, physically and emotionally" — but because of her insights into up-and-coming urban locations that are being built by "an ever-specializing transient workforce, an army of lifestyle brand ambassadors without business cards or the 401(k)." In other words, to satisfy both a cultural mystique and an eager clientele, baristas in non-chain city environments like Brooklyn are responsible for much more than making your latte; their job is to reflect the hippest aspects of the local atmosphere, with their tattoos and their ability to talk literature and tech, while being compensated at poverty levels and having no upward mobility. "The knowledge required to read a customer, to justify the processes and origins of that $12 cup of coffee, is just as specialized as knowing what a nut graph is," Osberg writes. She can only conclude: "These jobs are lesser because we made them this way."

Turn On, Tune In, Get Stuff Done The Complete Guide to Listening to Music at WorkQuartz

Years ago, I listened to the Elton John classic "Philadelphia Freedom" on repeat for eight straight hours while in my cubicle. If you've made similarly concerning decisions, it's worth taking a detour through this fun article, which breaks down the basic neuroscience behind music in the office. While the tips may seem obvious at times, I know I’m at fault for trying to read complicated documents while listening to The Band's story-driven lyrics. So don't do that: Music is best when you're doing repetitive tasks. And if you want to listen while doing something that requires a lot of concentration, try songs with steady rhythms and few lyrics. You also shouldn't listen to music all the time — the cognitive benefits of music wear off when songs are played constantly. Lastly, it's sometimes a good idea to listen to pump-up music to trigger an emotional response before a big meeting or event. This excellent tune, for example, is what I used to listen to at a previous job when launching new web content. Worked like a charm.

BONUS BITSUpdates on a Few Select Industries

This Is What a Job in the U.S.'s New Manufacturing Industry Looks Like (The Washington Post)

The Engineering of the Chain Restaurant Menu (The Atlantic)

Journalism Start-Ups Aren't a Revolution If They're Filled With All These White Men (The Guardian)

How One Company Contained Health Care Costs and Improved Morale

Instead of simply providing health insurance, savvy employers are tackling health care costs by supporting the whole employee—everything from their finances to their career development to physical health. This is not just good for individuals; it’s good for business.

The health of the American workforce is declining, reducing both productivity and company earnings. In response, more and more employers are providing Employee Assistance Programs (74% in 2012, up from 46% in 2005) and wellness programs (63% in 2012, up from 47% in 2005). But these programs rely on individuals to change their behavior — and often don’t significantly affect the bottom line when it comes to health care costs.

In 2008, TURCK, a leading manufacturer in industrial automation with 500 employees in the U.S., had robust health benefits and even offered a discount when employees completed a health assessment. But CEO Dave Lagerstrom realized, “I didn’t feel this approach was helping me become more healthy, so it probably wasn’t helping our employees either.” Instead, Lagerstrom decided to explore how TURCK could create a work culture that supports employee well-being, encompassing five dimensions: 1) career development, 2) work-life fit, 3) financial security, 4) community involvement, and 5) physical health.

Today, each participating employee (and his or her spouse or partner if covered by TURCK) still completes a health assessment and screening, but each employee also attends a one-on-one session with a coach (provided by TURCK) to set well-being goals for the year. To achieve these goals, each employee commits to three activities from a menu of options that includes everything from a phone consultation with a financial planner to volunteering for a favorite charity to participating in a 10,000 Steps Program. Employees are rewarded for following through on their goals with either a reduction in premiums or paid time off. Employees get to choose which.

This strategy has helped the company both flat-line health care costs and book record profits. In 2008, TURCK’s health care claim costs were $280.52 per member per month. Based on the rate of inflation for health care spending in the Minnesota market where the company headquarters are based, it was projected that TURCK’s cost would have risen from $280.52 to $387.20 per member per month. Yet, they have remained constant, amounting to a total cost avoidance of $4,680,000.

Not only has the company contained health care costs, it has also increased engagement and reduced turnover. Turnover at TURCK is around 2%, while the industry average is about 11% to 13%. Results from the most recent employee survey also reflect a strong sense of engagement—88% to 93% of employees agree or strongly agree with the following statements:

I give my best efforts each day.

I put in extra time and effort as needed to do my work effectively.

I intend and would like to stay at this organization for a year or longer.

I strive to exceed expectations for those I impact each day.

Interestingly, TURCK did not launch this program primarily to reduce costs. As Lagerstrom explains, “As CEO, it is my responsibility to create a culture where people flourish. If companies enter into a well-being initiative only to save money, I believe they will fail because it won’t feel real to employees. That culture—the ‘feeling’ employees have about how the company treats them—is the key to reaping the benefits of this approach in the long term.”

Here are four things companies should keep in mind when creating a well-being strategy:

Lead with values. “This process has to start at the top and has to be about the employees first,” says CEO Lagerstrom. “Well-being has to be woven into the very fabric of the company.” 100% of TURCK’s executive team and 75% of its extended management team participated in a leadership and well-being development track, called Lead by Example. This initiative encouraged leaders at all levels to focus on their own well-being and that of their teams.

Keep it convenient. Many of the activities are located right at the plant, making it very convenient to sign up. TURCK also has an onsite health center staffed by a physician assistant. Since the onsite clinic was opened in 2007, employees have saved over 6,000 hours in paid time off (PTO) hours by using the clinic on company time. Employees have also saved over $100,000 in clinic copayments. TURCK has benefited, too, with over $263,000 in productivity savings and $480,000 in direct medical savings through use of the clinic in 2012 alone.

Make it personal. When TURCK shifted its focus to well-being at the end of 2008, it was partially a response to the emotional turmoil of the economic downturn. “Rather than just focus on physical health,” Lora Geiger, who was an HR leader at TURCK says, “we asked people to consider setting a personal well-being goal on anything that was meaningful to them. One mom from our Inside Sales Team made a calendar each week for the special things she was going to do each day with her five-year-old daughter, and she fulfilled on her commitment.”

Share success stories and make it communal. TURCK highlights employees’ personal success stories — like achieving a fitness or weight-loss goal, leading a community initiative, or how a preventive health screening saved their life — in the annual open enrollment meetings and monthly newsletters. These “Well-Being in Action” stories not only inspire employees to set personal goals, they have also helped TURCK go from 42% to 77% of employees up to date on their preventative screenings in one year. Similarly, while each employee has a personal action plan, employees at all levels are involved in helping each other achieve their goals. Physical well-being is encouraged on a walking path through the plant, by exercise breaks that are led by peers, and by organized games of wallyball or racquetball at their free gym. These group activities promote physical health and social well-being because they are a fun way for coworkers to interact.

Our studies show that focusing on well-being, as TURCK is doing, can lead to an improved work culture, healthier employees, higher levels of engagement, lower costs, and even higher profits. It’s time for companies to move from a focus on wellness to a broader and more holistic focus on well-being.

Gauge Which Activities Aren’t in Sync with Your Strategy

Take this brief assessment for feedback on how to improve strategic alignment in eight key areas.

Most organizational leaders struggle to align day-to-day activities with strategy, even though they know it’s important to do. Almost 80% of the more than 1,200 senior executives recently surveyed by PricewaterhouseCoopers believe that their organizations have the right strategic intent — but only 54% think they’re executing that strategy well.

Why the gap? Let’s compare two fictional companies to see what’s involved.

The first — which we’ll call Company A — focuses on translating its strategy into action as quickly as possible. Right away, the senior management team converts its PowerPoint decks into a road show that explains the strategy, develops a comprehensive implementation plan, sets up a program management office, establishes steering committees, assigns roles, and even starts restructuring. But after six months the plan starts to falter. Leaders and their teams are strapped — and competing — for resources. Distracted by pet initiatives that have little to do with the new strategy, they revert to old habits. They struggle to manage tensions between units and to realize value across them.

Company B takes a different approach. Before rewiring operations, leaders:

wrestle with the nuances of the strategy

diagnose how well the organization’s activities are currently aligned with it

cease any strategically unimportant activities

identify capabilities vital to the strategy

establish decision rights

begin modeling behaviors that support the strategy

gauge performance and risks with leading and lagging metrics that reflect the company’s priorities.

This whole process puts leaders in a more constructive mind-set and tends to defuse political jockeying, defensiveness, excuses, and blame.

Company A’s leaders have intellectually bought into their strategy and execution plan, but through their discipline and hard work, Company B’s leaders have built emotional commitment, as well, which will give their efforts more staying power. As Company B’s leaders turn their attention to operations, they make sure all the elements — processes, people, capital and organizational structure, and technology — are in lockstep with what the strategy demands. Leaders help engage the rest of the organization by clearly articulating people’s roles and modeling the actions required to deliver results.

That’s what alignment looks like. It’s not easy, and it never goes off without a hitch. But in the end it’s actually much more efficient than diving right into a reactive, short-term operational overhaul.

Do you work for Company A or Company B? This brief assessment will help you gauge whether misalignment is holding your organization back.

Asking Whether Leaders Are Born or Made Is the Wrong Question

Are leaders born or made? When I pose this question to executives or HR professionals, the vast majority say that leaders are made; that is, leadership is something one can learn. Yet researchers have found traits, such as extraversion and intelligence, which differentiate leaders from others. This seems to imply that we can identify future leaders by looking at their traits – but we must be cautious when drawing such conclusions.

By failing to differentiate between leadership effectiveness (performance as a leader) and leadership emergence (being tapped for a leadership role), this research is often misunderstood and misused. In fact, inborn traits are more strongly associated with leadership emergence. That is, within a group of peers, those who are more extraverted or more intelligent tend to have more influence on the group. Does this mean that these same people perform better than others when placed in a formal position of leadership? Not necessarily.

Let’s look at the relationship between extraversion and leadership effectiveness. Some studies have found a relationship, but it is so weak that it is difficult to draw conclusions from it. A much stronger relationship has been found when looking only at particular types of jobs: extraversion predicts performance in jobs with a competitive social component; for example, sales. And if we look at extraversion in more depth, it can also predict other less desirable outcomes such as absenteeism.

What about intelligence and leadership effectiveness? Again, the relationship is surprisingly weak and can be disrupted easily. For example, if the leader is under stress, then it is no longer possible to predict the leader’s performance by looking at his/her intelligence. It seems that stress makes people behave in unpredictable – and perhaps less intelligent – ways. Interestingly, there is a far stronger relationship between leaders’ perceived intelligence (how intelligent they look to others) and how likely they are to be chosen as a leader than there is between actual intelligence and leadership. Apparently, when it comes to leadership, appearances are everything.

So are leaders born or made? What is this question really asking? If it is asking whether someone will emerge as a leader among a group of peers, then those types of leaders are born. But if it is asking whether someone will perform effectively in a leadership position, then that is dependent on the context, the type of job, and the person’s ability to develop leadership skills. This cannot be predicted by their traits.

Unfortunately, we often choose our leaders based on traits such as extraversion, charisma, and intelligence (or perceived intelligence). And then we wonder why their performance does not live up to our expectations.

Reporters Compare Ride-Sharing Apps to Taxis

To compare ride-sharing services with one another and with taxis, Wall Street Journal reporters used UberX, Lyft, Sidecar, and cabs to get to work for a week in Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, and Washington D.C. Over the course of more than 30 rides, prices on UberX averaged about 20% more than taxi fare, in part because of “surge” pricing during rush hours. Lyft came in second, costing a little more than taxis. Sidecar cost about 10% less than taxis. Cabs were fastest at getting passengers to their destinations, followed by UberX drivers. Sidecar and Lyft drivers took about 20% longer than cabbies.

Why the Greek Yogurt Craze Should be a Wake-Up Call to Big Food

In 2005, Hamdi Ulukaya purchased a yogurt factory in upstate New York that had been shuttered by Kraft Foods. He wanted to use it to produce a line of strained, or “Greek,” yogurt called Chobani. If you’ve been in a grocery store lately, you probably know the rest — the brand caught on quickly. But for years, as Chobani gobbled up market share, the major food companies stuck to their regular lines of yogurt. Chobani went on to become the second largest yogurt seller in the U.S. and cost General Mills, Dannon, and other established players billions of dollars in sales. And new reports say that Chobani is talking with investors about a deal that would value the company at $5 billion.

Food fads develop quickly in today’s marketplace. Consumers are more tightly connected now and are more likely to follow word-of-mouth (or word-of-keystroke) advice than in the past. Amid this changing environment, you’ll find rows and rows of marketing teams at the Mid-Western headquarters of America’s largest food companies — in no industry does marketing appear to play a more prominent role. But despite this manpower, “Big Food” missed Greek yogurt. As the dynamics of the American food market have changed, the industry that essentially invented the modern marketer has been slow to notice.

As the Chobani story shows, Big Food needs to make some changes, particularly to a customer-centric, as opposed to marketer-centric, marketing approach. This transformation holds lessons for all consumer-goods companies. And it requires companies to consider steps like these:

Give up some control and get nimble. Big Food has a proven formula for its products that involves controlling the message and the channel. Companies build consumer awareness through paid media and get products in front of customers by offering promotional dollars to supermarkets to display products prominently in the aisles. But entities such as social media, online grocers, and word-of-mouth marketing are adding a whole new dimension beyond traditional paid media. Companies need to experiment with other means of going to market, including launching products with specialty retailers and using social media and other tools to drive word-of-mouth (and keystroke) marketing.

Remember the difference between “good taste” and “tastes good.” Controlled experiments involving consumer taste preferences have taken food companies down a path of continuously fatter, sweeter, and saltier products. By the time Chobani entered the market, a single pot of traditional yogurt had come to contain as much sugar per serving as many desserts. Ulukaya has said he launched Chobani with almost no money available for promotion or advertising because “deep down I knew I had something very good.” To unleash food fads, companies need to have the same confidence and choose products that they can believe in.

End your obsession with ingredient cost. Big Food favors products with big gross margins — in part so that they have more to spend on needed marketing and promotion. One of the reasons that Big Food didn’t like Greek yogurt early on is because it costs more to make and contains less water than regular yogurt. Food companies should distribute their gaze more evenly across their value chain. Instead of focusing primarily on downstream activities such as packaging and promotion, they should also look upstream to identify promising natural ingredients. Great products can command premiums, and become popular with very little marketing spend. Kale, quinoa, or chia anyone?

Put the product ahead of the brand. Brand management has hijacked the most important part about food: the product. Food companies constantly narrow their focus on how to convey what the product means rather than what the product is. The fact that, for example, a suburban housewife is the center of a certain brand’s universe is important knowledge, but that insight can never trump creating a product consumers actually want to eat. Branded food companies should invest more in innovation and less on brand marketing.

Learn the art of “small ball.” Giant companies like P&G and Unilever tend not to be interested in product launches unless they offer hundreds of millions in potential revenue. It’s possible that had an established food company attempted to compete with Chobani from the start, they would have withdrawn the product because it didn’t meet initial sales goals. There are two ways to solve a “swing-for-the fences” bias. One is through M&A. PepsiCo is a leader at this inorganic approach — their partnership with Sabra unleashed a hummus craze that shows no signs of abating. Another is to put semi-autonomous incubator groups in charge of smaller and softer launches. General Mills’ Small Planet Foods, for example, operates semi-autonomously from the company’s mother ship in Minnesota, and has recently added several successful brands.

Shorten your development cycle. Alternative food companies use co-packers so they don’t require long-run investments in factories. They start by launching products online and in specialty channels instead of through traditional grocers. They dispense with large consumer surveys and test products directly with networks of loyal customers. All of these contribute to shorter development cycles and much lower costs for new product launches.

Big Food has become “big” as a result of a terrific success: their traditional marketing departments have helped generate billions in profits. But relying on one approach to marketing has left these players exposed in today’s fast-moving climate. If a company has only one way to go to market and think about its business, it limits its opportunity to respond quickly, flexibly, and to enter and exit fast-changing food categories in a timely manner. And that’s true for any consumer goods company.

March 13, 2014

Our Bizarre Fascination with Stories of Doom

Andrew O’Connell, HBR editor, explains why we find tales of disaster so compelling. For more, read his article, Why We Love Disaster Stories.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers