Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1457

March 7, 2014

Sometimes It’s OK to Procrastinate

There are two types of procrastination, passive and active. The first is the type our superegos, parents, and significant others are always warning us against: Getting stuck in uncertainty and failing to act quickly. But sometimes, unknown to our internal and external critics, we engage in actively putting things off, writes Anna Abramowski. Although we're fully capable of completing a task quickly, we choose not to, because we're focusing our attention on another goal that's more important to us. Unlike passive procrastinators, the active variety tend to be self-reliant, autonomous, and self-confident. In other words, active procrastination is nothing to be ashamed of. It can lead to inspiration and innovation. Best of all, Abramowski says, it can help us break out of from "productive mediocrity" — accomplishing a lot of tasks that don't add up to a hill of beans. —Andy O'Connell

What If Schedules Didn't Matter?Working Mothers See Penalties When They Adjust Work Schedules After Having ChildrenWork in Progress

It’s a sad commentary on corporate culture that women who try to balance employment and child-raising still feel like they're violating workplace norms. In a study of 2,000 employees, a team of sociologists found that women who worked part-time or took extended leave after having children felt stigmatized more often than did childless women who took comparable time off. Of course, women with children get a double whammy: They not only feel they’ve transgressed against workplace standards, they also carry the burden of having violated gender norms about what it means to be a good mother. Men, regardless of whether they had children, did not report feeling as though they were punished for working nonstandard hours.

That brings us to the issue of hours worked and compensation. Businessweek's Sheelah Kolhatkar recently analyzed research from Harvard economist Claudia Goldin, who found that "companies offering true, stigma-free flexibility and linear compensation — meaning the same pay per hour worked, regardless of when it is worked — have the lowest gaps in pay between men and women — and, in many cases, more women employees overall." In other words, letting go of ideas about what "normal" work looks like and where it takes place could boost equality — and possibly make mothers (and fathers) happier and more productive.

Inconvenience, Please The Problem with Easy TechnologyThe New Yorker

A piano, a frying pan, a typewriter, and a paintbrush are demanding technologies — they take time and practice to master. Automatic transmissions, instant mashed potatoes, and iPhones are convenience technologies, which require less effort to yield predictable results. Making something more convenient is one of the time-tested paths to innovation, disruptive and otherwise. Conveniences open up life’s pleasures to a wider range of people. But in this thoughtful piece, Columbia Law professor Tim Wu makes the case for inconvenience, pitting the advantages of doing more against the benefits of learning more. "It isn’t somehow wrong to use a microwave rather than a wood fire to reheat leftovers," he says. "But we must take seriously our biological need to be challenged, or face the danger of evolving into creatures whose lives are more productive but also less satisfying." —Andrea Ovans

The Long View Facebook's FutureWorking Knowledge

What will Facebook look like in 10 years? Harvard Business School's Mikolaj Jan Piskorski offers his predictions, and they don't involve hoards of teens abandoning the social network forever. Piskorski argues that the site will go from a retrospective medium, which we use to post about things that have already happened, to a prospective medium that will gather our real-time data and make it useful for both users and advertisers. He sees Facebook as "less of a website to visit than an invisible conduit to the most important aspects of people's lives." That conduit will, of course, entail the gathering of boatloads of personal data. It’s on this point that "Facebook will need to execute as flawlessly as possible," or everything could go awry. If the site's "main driver is to use the technology for invasive and intrusive paths toward profit, Facebook's future may well be questionable."

Dispatch from the Winner-Take-All Economy25 Highest Paying Companies for Interns 2014Glassdoor

The highest-paid interns are raking in something north of $80,000 (or they would be if you annualized their monthly stipends), underscoring the intensity of the war for talent, particularly among companies in the high-tech and energy sectors. Fully 18 of the firms that make Glassdoor’s list of the highest-paying companies for interns are based in San Francisco (suggesting a transfer of wealth not so much to the next generation of Google, Apple, Amazon, Twitter, and eBay employees as to Bay Area landlords). Topping the list is big-data-mining software firm Palantir, which is trying to entice the best young minds with $7,012 a month, though at least one Palantir intern claims that "very few people are there just for the money." Easy to say with more than $20,000 in your pocket at summer’s end. —Andrea Ovans

BONUS BITSThe View from Above

The Top of America (Time)

Has Privacy Become a Luxury Good? (The New York Times)

How the Elevator Transformed America (The Boston Globe)

‘My Years with General Motors’, Fifty Years On

For fans of management books, this month marks a big anniversary. It was fifty years ago that Alfred Sloan’s now classic My Years with General Motors hit bookstores, and immediately appeared on The New York Times’ nonfiction bestsellers list.

With recent editions out in Polish and Portuguese, Alfred Sloan’s memoir still commands attention for one compelling reason: because Sloan’s General Motors seemed to achieve the impossible. When Sloan took over the firm in the early 1920s, General Motors was a mess. Its founder, William C. Durant, had created the corporation by cobbling together more than a dozen smaller car and part manufacturers, with little obvious logic. Worse still, not one of the company’s assorted products could begin to compete with Ford’s Model T on price or quality. Most were losing money.

Yet in little more than a decade, each GM product line was turning a profit, and the corporation as a whole had established itself as the world’s premier automaker and the nation’s largest single employer. Moreover, Sloan did this by means of organizational mastery, without the major engineering breakthrough that other GM insiders believed was their only hope. Ford still may have produced the best car for the money, but Sloan’s GM trounced Ford Motors by producing the best product lines for the market.

It is harder, though, to pinpoint exactly what lessons today’s managers might take from what has been called “the best business book you’ll never read.” Fifty years on, Sloan’s My Years at General Motors might seem to have all the freshness of an insect in amber. The world it describes has largely vanished. In 1964 the biggest companies in the U.S. were in oil, autos, and steel, with Standard Oil, General Motors, U.S. Steel, Ford, and Gulf Oil heading the list. American manufacturers exported radios, televisions, and other appliances around the world. The country had a middle class. The ratio of a CEO’s pay to a laborer’s was tiny compared to today. At McDonald-Douglas, the company’s president received wages just 10 times the amount of the floor sweeper (today it would be a 1,000 times). The “organization men,” as sociologist and writer William Whyte called the troop of managers who populated these bureaucracies, expected lifetime employment in a single firm. In some ways, the large American manufacturers were the Downton Abbeys of American capitalism – hierarchical organizations, often located in manicured suburban settings, with elaborate written (and unwritten) rules of behavior. Moreover, they operated on a scale that is unthinkable in a business climate that prizes “nimbleness”: in 1960, GM had 500,000 employees on its payroll.

Yet, despite the wholesale changes in the business landscape, there are timeless lessons in My Years at General Motors. Sloan’s book describes in fascinating detail and (thanks to ghost writer John McDonald) clear prose the working out of a competitive vision — relentlessly, obsessively, and through all its permutations. More than any other volume, My Years reveals what it takes to build a company around a compelling strategy.

To appreciate Sloan’s book, consider the titanic achievement of his predecessor, Henry Ford. The history of the automobile industry can be understood as a series of dreams. When Henry Ford was young, the horseless carriage was a plaything of the wealthy. His dream was to “put America on wheels” by building a high-quality and affordable car — a dependable machine that would “take you there and bring you back.” Ford, an inventor with no formal training, had a brilliant mind for mechanical invention. He made his dream a reality when he built his colossal manufacturing plants and produced the Model T. It’s hard to overstate Ford’s achievement. He pioneered the largest industry of the twentieth century and, when he boosted his workers’ pay to a sky-high $5 per day in 1914, he became a worldwide hero. By 1920, America was on wheels. But that was the problem — once Ford had attained his dream, and the country had millions of Model T’s on the road, he simply made more.

Alfred Sloan’s dream took in what Ford missed in his single-minded pursuit of value for money: the importance of marketing. Sloan recognized that a market for something other than the Model T existed because American consumers regarded cars as something more than a utilitarian vehicle. Knowing he couldn’t beat Ford at his own game, Sloan aimed to change the game itself. His dream was to create a “car for every purse and purpose.” Despite his own origins as an MIT-educated engineer, he took inspiration from the “Paris dressmakers.” He introduced annual model changes in the mid-1920s and brought designers from Hollywood to shape new cars. My Years does not tell the story of improved efficiency, for sure. In fact, the marketing of cars, as Fortune reported in 1938, became one of the “most inefficient parts of the whole American economy …. [N]early one-third of the price you pay for a new automobile goes to cover the cost of getting it from the factory to you.” The price tag included costs for dealer’s expenses, sales commissions, convention fees, advertisements, brochures, promotional movies, and a whole lot more. But all of this ballyhoo exposed Ford’s Achilles heel: once America was on wheels, it was no longer enough to make the best car at the best price.

The lasting value of Sloan’s book is not really the dream, but the ambition, detail, and scale with which he commercialized it. Sloan was the consummate organization-builder. His vision was evident in the very structure of the new multidivisional firm, which divided the American automobile market into five price segments. The heads at Chevrolet (the low-priced unit), Pontiac, Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac (the high-priced unit) had authority over their divisions. A central office kept track of finances and the allocation of resources. “Strategy” led “structure,” as historian Alfred D. Chandler (who researched Sloan’s book) put it.

Ford had disdained organization and vowed to have “no line of succession or of authority, very few titles, and no conferences.” At Ford, all decisions came from the top. At General Motors, decision-rights were far more decentralized. Richard Grant, the former salesman who headed Chevrolet, fought aggressively to erode Ford’s profit in the low-price sector by sending salesmen door-to-door looking for homes with a Model T in the driveway. Whenever one was spotted, which was often, a Chevrolet salesman would get out and offer the owner a test drive in the new GM model. Chevrolet sales soared. GM was a behemoth, but its decentralized structure gave divisional leaders like Grant the freedom to direct strategy for their own product lines.

The power of Sloan’s strategy was not to last, of course. As Ford found out, dreams held too long can become tombs. Quality engineering and efficient production were never GM’s main focus, and over time the deficiencies began to show. In the late 1960s, a Mercedes-Benz 250 was safer, cheaper, and better engineered than the bloated and highly touted Cadillac Eldorado; after the oil crisis hit of the 1970s, Chevrolet lost out to the fuel-efficient and reliable Japanese imports. As with GM’s cars, so went its organizational vision.

Just four years after Sloan published his memoirs, a handful of scientists and venture capitalists in Mountain View, Calif., came together to create Intel, a semiconductor chip manufacturing company. Its founding marked the beginning of a business culture that strove to avoid the costly entanglements of large fixed-plant organizations like GM — a world that came to be populated by entrepreneurs rather than “organization men.”

What Shake Shack Knows About Growth that McDonald’s Has Forgotten

The idea that organizational growth comes from doing a few things well is popular and proven. But debate remains on how to direct your firm’s focus as you grow.

There are many options. With a technology focus, you might manage to launch a successful breakthrough, but your success will be short-lived because sustaining a technological advantage today is so difficult. A sales focus fails to deliver a profitable market leadership position because it favors short-term revenue growth and customer acquisition over sustainable margins and customer loyalty. Companies have been right to give more attention to customers in recent years, but when understanding customers, developing value propositions, and applying brand values are considered responsibilities only of the marketers in your organization, your company lacks the alignment and integration needed to produce a complete and coordinated superior customer experience. And, as a customer-focused organization, you may be embracing a concept that’s popular now, but ultimately you’ll run up against the reality that it is neither financially nor operationally feasible for a scaled enterprise to satisfy all desires of all customers.

The bottom line: if your growth plan is not grounded in your brand identity, it will likely disappoint in delivering the results you seek. The problem with the areas of focus above is that none of them actually define what your company is and what it stands for. They are merely the means for executing and expressing your core, your essence — in other words, your brand.

Great brands use their brand identities as their one true focus because that’s the only way to ensure continued relevance and resonance with customers — and continued value to shareholders.

Organizations that grow by staying true to their core brand values and identity are successful in the long term because they don’t get swept up by changes in tastes, events, and trends. And with a strong brand focus, it is much easier to make swift decisions that are consistent with the values the company hopes to embody for its customers. So the leaders behind great brands drill down to their core values and execute on them relentlessly, even when it means saying “no” to attractive short-term opportunities. Over time customers learn exactly what the brand stands for and come to trust that the brand will deliver it every time.

A tale of two brands illustrates the value of brand focus. McDonald’s, the $27.5 billion corporation with over 34,000 locations worldwide, recently reported its fifth consecutive quarter of disappointing sales. Shake Shack, the burger-and-shake chain with 34 locations, continues to open profitable units around the world. The CEO of McDonald’s admits the company has “lost some of our customer relevance,” while Shake Shack enjoys such strong appeal that the lines to get into its locations are as legendary as they are long.

While the difference in the scale and complexity between the two organizations is significant, the importance of having a focused brand is the same. Leading the list of reasons for the golden arches’ recent poor performance is the company’s seemingly scattershot approach to innovation. It has chased multiple priorities such as McCafé, its value menu, and new products including so-called healthier ones that actually aren’t even that healthy. These disparate efforts have compromised operational excellence. One analyst observed that “as with its admittedly overcomplicated menu that now has over 180 items, the company’s priority list seems just as long.” If the company had kept its focus on its brand essence — appealing to the child in all of us — it would have managed to diversify in more integrated and distinctive ways, and it would have steered clear of menu items, promotional strategies, and operational developments that detract from delivering a playful experience.

McDonald’s diffused focus starkly contrasts with the singular brand focus behind Shake Shack’s success. Shake Shack has become one of the category’s most remarkable success stories in recent years by committing and staying committed to its brand mission: being “the best burger company in the world.” Its CEO, Randy Garutti, explains his organization’s commitment to the principle “Do what you want to do really well in its most basic version.”

From selecting new restaurant sites, to hiring and developing employees, to creating the unique look of each location, the folks at Shake Shack use their brand values as a compass and their heritage as a guide for everything they do. Speaking about the chain’s first location in New York City’s Madison Square Park, Garutti reports that he and his team make decisions by “running everything through the filter of when we built this little restaurant behind us.” Out of an expressed commitment to an extraordinary burger experience, they find themselves frequently rejecting otherwise-enviable growth opportunities, such as catering or operating a food truck, because they fail to square with the company’s brand identity.

Shake Shack’s brand focus has also led the company to make some unpopular decisions. For example, last year it replaced its frozen, crinkle-cut French fries with fresh, hand-cut ones. Although Garutti and his team knew that some customers would pan the change, they went forward with it because the new item is fresher and higher quality and tastes better – each a defining attribute of the Shake Shack brand. And the company has only continued to grow and attract more fans.

Whether your company is large or small, or has been around for decades or days, focusing on the core of your brand — and staying committed to that focus — is the key to successful, sustainable growth.

America’s Long and Productive History of Class Warfare

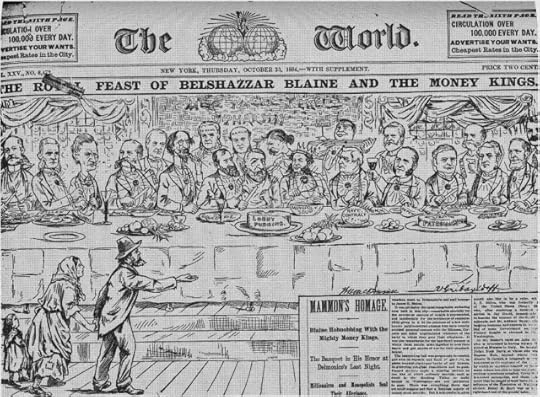

Six days before the election, the Republican nominee for president attended a fund-raising dinner at a posh New York restaurant. Two-hundred of the country’s richest and most powerful men were on hand. The next day, they were confronted with this atop the front page of one of the city’s leading newspapers:

This particular scan is from the historical-cartoon site HarpWeek, but the drawing has long been in the public domain — it ran in the now-defunct New York World on Oct. 30, 1884. The candidate was James G. Blaine (the droopy-eyed fellow in the center of the picture who is about to dig in to some Lobby Pudding), and the man who subjected him to this harsh treatment was Joseph Pulitzer, who had bought the World the previous year and was rapidly building it into the most popular and powerful newspaper the nation had ever seen.

The cartoon that Pulitzer had Walt McDougall and Valerian Gribayedoff draw was just the beginning — although what a beginning it was, featuring the likes of Jay Gould (seated just left of Blaine) and William Cornelius Vanderbilt (son of Cornelius, seated just to the right of Blaine with the awesome bifurcated beard, although according to historian Richard John he wasn’t even at the dinner) feasting on political spoils at Delmonico’s while a poor family begged for scraps. As James McGrath Morris recounts in his wonderful biography of Pulitzer:

The World revealed every aspect of the dinner, even though the organizers had done their best to bar the press. From the Timbales à la Reine and Soufflés aux Marrons upon which the men feasted to the thousands of dollars pledged to buy votes, no detail was left out. Even more damning, the main story began with a one-paragraph account of men who had been thrown out of work at a mill in Blaine’s home state and were now applying for assistance or emigrating to Canada.

Some of this was partisan politics: Pulitzer, himself on the ballot as a Democratic candidate for Congress, supported Blaine’s opponent, Grover Cleveland. New York was the most important battleground state, and the World’s assault was widely credited with handing the presidency to Cleveland a few days later.

It wasn’t just that, though. In an era when America’s first industrial magnates were amassing unheard-of riches and using it to mold the political system to their liking, resentment of that wealth and power was widespread. Pulitzer’s attacks on the rich helped bring in readers, so many that before long he too had become a multimillionaire with a yacht, a house not far from Vanderbilt’s on East 55th St. in Manhattan, and a membership in the Jekyll Island Club.

By that point Pulitzer had toned down his paper’s attacks on the rich — yet another example of American capitalism’s remarkable ability through the years to coopt its critics by sharing its spoils with them. But the ferociousness of his initial assaults, and of many others aimed at the tycoons who dominated the country’s late-19th-century Gilded Age, gives the lie to the complaint voiced these days in some circles that current resentment of the rich is somehow unprecedented or un-American — or even reminiscent of Nazi Germany.

Have these people never heard about Teddy Roosevelt excoriating the “malefactors of great wealth,” or his cousin Franklin getting Congress to raise the tax rate on top incomes past 90%? Americans have been pillorying the rich on and off for more than 200 years, and our economic system has survived and mostly thrived. In fact, the political and labor-relations compromises occasioned by what you might call class warfare have on balance surely made the country stronger.

What’s been unique, or at least highly unusual, has been the environment in which entrepreneurs and business executives were able to operate from the late 1970s through the early 2000s. Taxes dropped, high-end incomes exploded, and hardly anybody complained at all. Far from complaining, in fact, the news media for the most part celebrated the recipients of those exploding incomes for their boldness, creativity, and economic importance. It was a pretty stinking awesome time to be a plutocrat: You got to make billions of dollars, pay far less in taxes than you would have a quarter-century before, and get your face on the cover of Forbes or Fortune (or maybe even the top of your head on the cover of HBR).

Fourteen years ago, with the dot-com bubble fizzling but the rest of corporate America seemingly still going like gangbusters, the great management journalist Geoff Colvin wrote a column in Fortune titled “Capitalists: Savor This Moment.” An excerpt:

The business culture is triumphant. Not just for those in authority but for most of society, business is at the center, and that’s pretty much okay with everybody. It doesn’t feel remarkable to us for the same reason fish don’t notice water; we live in it. But step outside the moment and look at commerce’s role in the culture. It’s unprecedented.

Colvin’s conclusion was that this just couldn’t last. He wasn’t sure what would replace it, and even now it’s not obvious what will. By the numbers it’s still a pretty awesome time to be a plutocrat, but clearly the mood has changed. It’s important to remember, though, that the anomaly is not the current mood of skepticism of business and the rich. It’s what preceded it.

Tech Firms’ Investments in Workers Often End Up Benefiting Competitors

When they change jobs, high-tech employees bring a lot of previously acquired know-how with them, boosting their new companies’ productivity. A study of hundreds of thousands of workers over 20 years by Prasanna Tambe of New York University and Lorin M. Hitt of The Wharton School suggests that the productivity-growth effect of this flow of workers is 20% to 30% as large as that of the companies’ own IT investments. The finding at least partially explains why many firms consider it advantageous to locate in places like Silicon Valley, the researchers say.

Stop Using Your Inbox as a To-Do List

Do you leave emails in your inbox so that you remember to read or tackle them? If so, you’re using your email to manage your tasks—and those are actually two very different things. Using a separate task manager, one that ties in closely with your email, can help you spend less time sifting through your inbox, and more time getting your most important work done.

Why do you need to separate these activities out? If you’re conflating email and task management, then the job of simply communicating–reading and replying to your messages–gets bogged down by all the emails you leave sitting in your inbox simply so you won’t forget to address them. (And there are probably a few to-do reminders in there that you sent to yourself!) This approach also makes managing your to-do-list problematic: when you need to quickly identify the right task to take on next, nothing slows you down like diving into your inbox to scroll through old messages.

The reason so many of us fall into the trap of conflating email and task management is that email is inextricable from much of what we do in work and in life: many of our tasks arrive in the form of email messages, and many other tasks require reading or sending emails as part of getting that work done.

Luckily, there are many fantastic task managers that recognize the inextricability of email and task management without lumping the two in together. The best task managers not only provide you with a single place to capture the tasks you need to get done; they also make it easy for you to add tasks by email. But unlike email they can also track things like what is complete or incomplete, when each task needs to get done, what project a task is related to, or where you need to be in order to do it.

While there are those who solve this problem by simply tracking their to-dos using the task manager within Outlook (or another email platform), that approach comes at too steep a cost. Keeping your tasks in your email program means you can’t close that program (and its attendant distractions) when you want to plow through your task list. Having both activities as part of one application also means that you’ll still have to flip from one view to the other; even if you open a separate window for your task list, you risk losing sight of it in a sea of open emails. Most crucially, defaulting to the task manager that is built into your email client means you don’t get to choose the particular task manager that works best for your particular kind of work, or work style.

There are many task management systems available, each aimed at users with different needs and work styles. Here are some of the best candidates to consider as you search for the one that’s right for you – as well as advice on how to integrate each one with your email system:

Remember the Milk. For those who need a task manager that will work for both their personal to-do lists and team collaboration, RTM is a slick & snappy web-based task management tool with loads of great features that syncs across a large number of other devices, operating systems and web applications. Whether you depend on an iOS, Windows or Android phone; Google Calendar or Outlook; Evernote or Twitter: RTM has an app or extension for you.

And you can add tasks to Remember the Milk via email easily once you get the hang of formatting the messages.

Things. Apple loyalists who place a premium on the aesthetics of their software will like this well-designed task manager, which keeps tasks neatly in sync across all Apple-made devices (though you have to buy separate versions for Mac, iPhone and iPad, which adds up). Options to view tasks by project, context or timeline make it very easy to see what you need to do at any given moment in your day.

Things also provides a handy feature that’s one step up from emailing yourself tasks: quick entry with autofill lets you highlight an email in your inbox and then use a single keystroke to create a new Things task that is pre-filled with the selected email text. There is also a very useful (if geeky) workaround that gives you even more control over creating tasks directly from Apple’s Mail.app.

OmniFocus. Mac users who use David Allen’s Getting Things Done approach to productivity may take to OmniFocus, which bakes Allen’s methodology right into the software. It encourages you to attach contexts to each task (like noting whether this is a task to be done by phone or on the computer, during the workday or on your commute home) so that you take on the task that is most feasible whenever you turn to your list.

OmniFocus users can use a simple and elegant service called Mail Drop to email tasks directly to OF. There’s no special formatting to learn, and as an added bonus, it’s easy for OF users to take advantage of some really cool IFTTT recipes!

Toodledo. If you’re looking for something really powerful and flexible, Toodledo’s web-based task manager allows you to add tasks and sub-tasks to lists, which can be organized into folders, goals, contexts or outlines, each of which offers different ways to parse the tasks. There are collaborative features available to paid subscribers, and TD syncs to popular calendar applications. One of the neat things about Toodledo is that they partner with Carbonfund.org to offset the electricity used in their operations. As far as I know, they’re the only task manager that can claim to be running a carbon-neutral operation.

The trade-off for all that power and complexity is that adding tasks to TD via email can be somewhat onerous. Like the application itself, Toodledo’s email interface offers very powerful options, but it’s got a steep learning curve.

Basecamp. While I wouldn’t recommend Basecamp for someone those seeking to manage just their personal tasks, if you’re already working in an organization that uses Basecamp to manage collaboration it’s a good option. Then you can set up your personal task list as a project named something like “My Tasks” rather than using completely separate applications for your personal and team-based tasks. The many tools that sync with Basecamp give you easy access to your task list when you’re on your phone or offline.

Turning an email into a Basecamp task is just as easy: just follow their simple instructions to forward it to your account.

What I use now: Evernote + Reminders + Followup.cc. For those who tend to get lost in the sea of their own overgrown task lists, consider dividing that list up to make it easier to deal with. First make a weekly list that contains only your most crucial tasks or deliverables for the next five days. If you use a note-taking tool like Evernote, keep your task list a click away by placing all these tasks in a separate “Tasks” notebook or folder and creating a prominently-placed shortcut to it in your Evernote sidebar.

As with more traditional task management tools, you can forward your emails to Evernote; it then becomes a note and when you need to refer to it, you can do a quick Evernote search–or if you’ve filed it, click on the relevant notebook.

In addition to the big things that go on your weekly list, you probably have a lot of smaller tasks to keep track of: an email you need to remember to write or a card you need to send. Use simple timed reminder tools for these smaller items. You can use Evernote’s own reminders feature for that purpose, but it may be easier to use a separate reminders tool like the default Reminders app that syncs across all Apple products.

And if the thing you’re trying not to forget is an email – maybe one you need to reply to later, or one you’ll need to follow up on – you can get that email out of your inbox by forwarding the email to followup.cc. It will come back to you at the time you specify, when you are actually in a position to act on it.

This particular combination of Evernote, timed reminders and followup.cc is what I use now. Using reminders and followup.cc to not forget the little stuff has allowed me to keep a very minimal list of my major tasks; and because I’m not getting bogged down in an inbox that’s overflowing with a list of implicit, tiny to-dos, I have more time to get those major tasks accomplished.

But I won’t pretend that this system is going to be my Ultimate Task-Fighting Champion for the next decade: if there’s one thing I’ve learned from trying dozens of task and project management tools, it’s that the best choice of tools varies as much from year to year as it does from person to person. Experiment with a few different email-friendly task managers to find the one that’s right for you now, and recognize that your needs, preferences and toolkit will almost certainly change over time.

My new ebook from Harvard Business Review Press, Work Smarter, Rule Your Email , gives more advice on how to use email to support your work – instead of letting it crowd out the tasks and projects on your plate.

March 6, 2014

Is Work-Family Conflict Reaching a Tipping Point?

60-Second Drills Can Sharpen Your Business Reflexes

After exiting the crowded auditorium where Colts quarterback Andrew Luck publicly wished that the NFL would develop “a football equivalent of pitch count” to reduce injury at his position, I headed left toward a series of large posters mounted on display easels in the hallway.

Each display showed complex statistical formulas, data visualizations, and excerpts from research papers presented at this year’s MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. Groups of three or four attendees clustered around each poster as if at an art gallery, nodding appreciatively to convey understanding or pointing to ask, “What does this mean?”

This year, more than 300 papers were submitted by researchers from the world’s leading academic institutions and corporate R&D groups, but only 13 were accepted for the conference. I’ve studied the posters and scanned the papers and am struck by how temporally exacting the leading edge of sports analytics has become. Thanks to new wearable technology and video analytics techniques, each minute (or less) of a game offers researchers increasingly precise modes of analysis and insight.

This new world also offers fresh ideas for managers in non-sports businesses. Here are four challenges analytics can help solve, each with a 60-second drill. There’s a lot to be learned in minute.

Spot faulty decision-making patterns. You might think you are fairly reliable when making spur-of-the-moment decisions during meetings or sales calls. But is it possible that your decisions are consistently off-base compared to routine decisions made by others in your organization or profession?

Using video of nearly every game over the last two NBA seasons, this paper analyzes the split-second call tendencies of referees. It found that many refs call violations at rates significantly higher or lower than the professional average; thus, understanding a decisions-maker’s tendencies can be “leveraged” as an advantage.

60-Second Drill: Conduct a data-gathering exercise of your own personal inclinations during your next meeting. Track a few key suggestions and who made them. Look at your tracking notes later on, asking yourself whether you have default feelings about the types of solutions mentioned (“I can’t stand new technology”) or who made them (“I really like this guy!”). Are these defaults resulting in predictably off-kilter decisions?

Recognize and quantify bias in new ways. Situational biases, like the fear of failure in some moments more than others, change how routine decisions get made. For instance, are you more likely to feel pressure to veto the standard 5% increase to the R&D budget just after your stock price took a hit?

By analyzing more than 1 million pitches from 2009-2011, this paper uncovers each MLB umpire’s aversions to miscalling strikes in certain situations. It found that for more pressure-packed decisions, such as calling a third strike, an umpire needs to be 64% sure it’s actually a strike half the time. By comparison, “if an umpire is unbiased, he would only need to be 50% sure that a pitch is a strike in order to call a strike half the time.”

60-Second Drill: Before your next decision, ask yourself whether and how an increased sense of pressure might bias the way you see a given situation; look carefully at your judgment of the facts, for example, or the data at hand.

Deconstruct a skill. Let’s say your boss just asked you to lead a critical new initiative, requesting a shortlist of people you’d like on the team. To assess needs and skills, you might be inclined to think in terms of generic notions of expertise. You might put a “coder” or “marketer” on your list, for example.

But imagine that you could get a totally new kind of granular insight on skills, grounded in data drawn from real-life practice rather than conventional categories. In basketball, for instance, generic skills are now being deconstructed in real time, allowing for more effective analysis of skills and assessment of performance. For instance, using tracking technology, researchers in this paper determined that the generic skill of rebounding in basketball is actually three distinctive skills: positioning, hustle, and conversion.

60-Second Drill: Identify your number one skill, the one you’re known for. Are there hidden or tacit sub-skills that underlie its successful application and outcomes? Jot down ways you could market these newly uncovered sub-skills to clients.

Track decisions in real time. During an important meeting, you and your colleagues might make dozens of small decisions that culminate in one big decision, like taking a shot at entering a new market with an existing product.

Imagine if you could quantify the contribution that each decision makes to the final outcome. Using optical tracking data to identify every small decision players make during a game — “whether it is to pass, dribble, or shoot” — this paper describes how real-time analysis of decisions can allow us to assess the value of an individual’s contribution in fundamentally new ways.

60-Second Drill: After your next meeting, identify a small decision that was made toward the beginning. Reflect on the ways it might have influenced later decisions, created value, and influenced the final outcome.

Why Are Some People So Critical?

Harsh critics are often talented, intelligent, and productive people. Unfortunately, they have a flaw that compels them to disparage others – almost, at times, as though they are diagnosing an illness in need of eradication. It seems they’re living according to the famous quip by Mark Twain: “Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits.”

In the language of the self-help and recovery movements, these folks are often suffering from a disorder known as, “If You Spot It, You Got It [IYSIYGI].” It works like this: You notice that colleague X has what is, in your mind, is an affliction. You then take it upon yourself to castigate him for his affliction — irrespective of whether or not it impairs his on-the-job performance or has a negative effect on group morale.

What makes this dynamic so ugly is that unbeknownst to the person under attack, the critic is being driven to criticize by a repressed-and-intolerable feeling that he’s “got” what he deplores in others.

For instance, years ago a client of mine and I were having dinner when he asked if I could help with a dilemma: “Diane, my comptroller, a woman 100% dedicated to the business, is also nastier than a junkyard dog. She doesn’t just monitor spending; she beats people up for what she sees as waste, failure to stick to protocol, issues with record-keeping… nothing major, but stuff that is technically wrong. If she assumes you are fudging parts of expense reports — say, claiming a lunch that’s not 100% business-related — she’ll attack you like Muhammad Ali in his prime. She assaults my EVP of sales so regularly, he vows to quit if I don’t fire her.”

My client was not prepared for my response: “I’m willing to bet Diane’s cooking the books so she can pocket cash.”

After catching his breath, my client took my bet. “Diane’s so honest, she could be a priest if the Pope allowed women to serve in that role,” he said.

But within a year, he was obligated to buy me a rare box of Cuban cigars after losing our bet: it turned out that Diane had been embezzling funds for 20 years.

That’s an extreme example of IYSIYGI behavior, but whether it’s a strong or a mild case, it’s a form of what psychologist call projection: A psychological defense mechanism that enables a person to deny their own issues by attributing those traits to others. Projection lets us condemn the traits or we find distasteful, repugnant, or worthy of punishment. IYSIYGI behaviors are, at times, benign –like me chiding my wife for leaving countless pairs of shoes around the house while my bonsai workbench looks like an earthquake hit it— but typically it is not. Ongoing IYSIYGI assaults can become significant threats to company morale.

When I bet my client that Diane was engaged in criminal behavior I was behaving “criminally” as well: Stealing candy from a baby. After studying IYSIYGI defensive tactics for years I knew that anyone who evinced hyper-rigid moralism –coupled with an intense bias against transgressors— was likely to terribly flawed.

In a very real way, Diane and all who condemn others owing to IYSIYGI drives are caught up in Shakespearean “doth protest too much” defensiveness. The anxiety that your own component parts are out of order –not the flaws of someone else— is the emotional pain that prompts an IYSIYGI attack.

IYSIYGI behavior is a fairly deep-seated problem that needs a clinician, not a coach, to resolve. That said, there is much that managers can do to minimize this dynamic on their teams.

The first step is to ignore faultfinders and instead reward problem solvers. In my opinion, we have become a nation obsessed with reproach: quick to jump to conclusions, take offense, and chide each other. The effect on our politics is bad enough, but it’s also been costly to our companies – and our relationships. Rather than assume that a problem has been caused by somebody’s ill-will, take a “stuff happens” attitude and simply ask the person or people closest to the damage to address it.

The second step is to encourage transparency – and forgiveness. The simple act of confessing your foibles can be incredibly beneficial. And learning from your confessor that you are not alone, that you are more “normal” than you assumed, is a major stress reducer. Finally, learning to be more patient with your own flaws will help you be more patient with those of others.

Finally, make sure that negative feedback is always given in the context of what can be done about it. Arguably, the worst thing IYSIGYI critics do is metaphorically curse the darkness while refusing to light a candle.

One executive who I was hired to coach, a man universally disliked by his direct reports, kept asking me, as a rhetorical rationale for his department’s under-performance, “How can I soar with the eagles while surrounded by turkeys?” I soon tired of this defense and recall snapping at him, “To hell with soaring… why don’t you just fly out of the barnyard so we can look at how you can do your job without justifying failure by fault-finding?” As bad as this intervention was, it served its purpose in that the executive admitted that he struggled to relate to his staff — and needed to learn to do so.

Still, in hindsight I wish I’d told that man, “Why not try to free yourself to soar by adopting the wisdom of Mahatma Gandhi: ‘Hate the sin, love the sinner.’ If you do, you’ll be amazed at how rarely your direct reports interfere with your flight plans.”

How GE Gives Leaders Time to Mentor and Reflect

It is 6:00 a.m. David is starting his first day as the “leader in residence” at Crotonville, GE’s global leadership institute, with a jog around the running trail with a couple of twenty-somethings who are half his age and might be five levels below him on an org chart. Their run is companionable; their discussion, candid. It is a serendipitous moment of connection that the three will always share.

David is one of our top executives, and he has stepped out of his day job as the head of a major GE business to make another kind of investment in the future of the company: He will spend this entire week teaching, coaching, mentoring, and learning with about 250 participants — high-performing managers and individual contributors who have come to campus from around the world. David and others who rotate through the position are helping to achieve the purpose of Crotonville: to inspire, connect, and develop GE’s talent.

The leader in residence position epitomizes our belief that a great leader is a great learner. It models both our cultural value of expertise, which encourages a deep knowledge base as well as a passion to develop others, and the GE leadership philosophy, which holds that when one person grows we all grow, and together, we all rise. And it allows David and other senior managers to take the time to reflect on their own leadership styles — an opportunity that they rarely get in the regular rhythm of their jobs.

After his run, David rushes off to a breakfast meeting where he talks to a group of first-time managers. At 8:30, he attends a session on the neuroscience of success with a group of mid-career high-performers. At 10:30, he hosts one-on-one coaching sessions, each about 30 minutes long. In the afternoon, he teaches a class on values, offering his take on the blueprint for leadership at GE. He then conducts “speed coaching” sessions with about 10 early career leaders: intense, five-minute discussions centered on a few focus areas such as personal brand and navigating the organizational matrix. By late afternoon, he is involved in brainstorming about next year’s curriculum, providing the faculty with a unique view into future business requirements. He tops off the evening with a live video meeting on customer focus with a group of leaders in a training program in Singapore. At the end of the day, he heads to the campus bar, where he spends the next hour chatting with all the participants.

Launched in 2010, the Leader in Residence program is emblematic of a broader shift from prescriptive to collaborative learning taking place at Crotonville and elsewhere. In a complex environment, learning comes from a combination of discovery, dialogue, experience, reflection, and application. At Crotonville, we bring people from all over the world and from different businesses and contexts. We have to create the opportunity for each person to teach and learn, simultaneously, enhancing everyone’s perspective. David, like other leaders, uses this as a listening post — a venue to capture what’s happening around the company and the world in an encapsulated way…with Crotonville providing the opportunity to listen, test, validate, and absorb on the one hand, and to share, push, elaborate, and support the students on the other.

In all, the program has enabled some 75 of our top leaders and thousands of participants to connect on a human level and to reflect on work, self, and career in a way that would never be possible in either a traditional classroom or office setting. By giving leaders access to deeper levels across the organization, and, in turn, providing participants access to senior leadership, we have created greater cohesiveness throughout the company. We have never had a problem filling out classes even during the most trying of times. Based on the success of the program, as measured through participant surveys and feedback, we recently launched a global version (74% of Crotonville experiences are delivered outside the United States currently).

In fostering a learning culture and deepening connections among leaders at all levels, we have found that we can drive better outcomes that accelerate individual growth and strengthen the talent pipeline.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Meet the Fastest Rising Executive in the Fortune 100

If President Obama Can Get Home for Dinner, Why Can’t You?

To Get Honest Feedback, Leaders Need to Ask

Don’t End Your Career With Regrets in Your Personal Life

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers