Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1456

March 10, 2014

Entrepreneurship Always Leads to Inequality

“Inequality is bad.” “Inequality is dangerous.” “Our system is at risk due to increasing inequality.”

Wealth inequality is on everyone’s minds these days: citizens, political leaders, economists, policymakers and yes, business leaders. Unfortunately, simpleminded thinking and insensitivity are often clouding the conversation. Deservedly vaunted venture capitalist Tom Perkins’ callous, arrogant and elitist recent comments should not serve as an expedient excuse to overlook an important “dirty little secret” about entrepreneurship, the acknowledged engine of economic growth: successful entrepreneurship always exacerbates local inequality, at least in the short run.

The $19 billion sale of WhatsApp’s to Facebook made Koum and Acton, overnight, vastly wealthier than their next door neighbors. The Boston Innovation District’s meteoric real estate prices are pushing the very entrepreneurs who made the district sexy towards neighboring districts where rents have not tripled since 2010. Tel Aviv’s “Cottage Cheese Protests” in 2011 stemmed in part from the entrance of newly-exited wealthy entrepreneurs into the city making it too expensive for “normal folk” to live in, with its nouvelle cuisine restaurants and ten million dollar Mediterranean penthouses blocking the views of the grandmothers whose parents settled the city a century before. The brand new Google Buses protest movement is fueled by similar fears. Seniors and the disabled worry they’ll be evicted to make room for well-paid and well-paying urbanizing tech workers cum stock-optionees with Tesla parking spaces worth more than a room in a public retirement home. In Seattle, home of Amazon and Microsoft, a protestor waved a sign, “Gentrification Stops Here.”

Inequality, in the broadest sense, is precisely, and perhaps paradoxically, what entrepreneurship is all about: entrepreneurs use their wit and grit to burst into new markets and generate extraordinary wealth, sometimes very quickly, more often over decades. Along the way, entrepreneurship rewards smart and risk-tolerant investors (who helped build the success) with wildly above-market (read: unequal) financial returns. The most successful entrepreneurship is disruptive — a term entrepreneurs these days have donned as a magic mantle: “We have a disruptive business model, a disruptive technology, and will disrupt the market” goes the startup pitch. Amazon has disrupted book stores and other retail chains, Zipcar disrupted car rentals, Netflix is disrupting cinemas and cable companies, Airbnb disrupts hotels, and Bitcoin may disrupt the payment industry. But the meaning of “disruptive” was never meant to be pure and all-positive: its synonyms include “troublemaking,” “disorderly,” “disturbing,” “unsettling,” and ”upsetting.” With all the buzz around disruptive innovation as a driver of business success in recent years, it’s important not to forget this original meaning.

Entrepreneurial success is intrinsically lopsided, a natural outcome of creating extraordinary value for customers. Entrepreneurship — if it succeeds — will always be, by definition, about the top one or two percent. It is about being the best of the best, about jumping over hurdle after hurdle on the way to the gold medal in the Olympics of enterprise, and leaving competitors in the dust.

Entrepreneurship, per se, can create many social goods. It can push innovation, can create dignified employment, can improve quality of life, can contribute to fiscal health through taxes, and does (at least in a few countries, including the US) dramatically boost philanthropy.

As I have argued in my book, successful entrepreneurship can also make housing unaffordable, increase taxes, and elevate the cost of personal services; it can deplete public goods such as education and health by giving the newly wealthy a simple and immediate work around public systems that don’t function well. Entrepreneurship can displace loyal legacy suppliers or products, along the way putting good people out of work, disorganizing and reorganizing supply chains and on the way down, depleting the wealth of the shareholders of deposed market leaders.

So is inequality, when it is directly created by entrepreneurs, good or bad?

For sure, without a system that ensures merit-based mobility, inequality can become a canker that infects and spreads. When the top 1% keep getting richer and the bottom 20% or so lose hope, inequality can become hardwired into a social structure and can keep people stuck, creating a vicious cycle of loss of ambition, loss of success, and loss of worth, both psychological and tangible.

But inequality can also be a great motivator, can fuel ambition, can bolster achievement, and can foster innovation. When my neighbor or friend or fellow citizen embarks on the entrepreneurial venture and is one of the fortunate few who succeed, this also may inspire, ignite my dreams, and shine a light on a new path to accomplishment and upward mobility that was previously obscured.

What should we do? I do not have all the answers, and I do not think there are panaceas. But I am sure that honest, clear-headed dialog will help. I am sure that whitewashing reality and sweeping entrepreneurship’s dirty little secrets under the rug will not help. Blindly ignoring the fact that entrepreneurship creates acute inequality will keep our society from benefiting from entrepreneurship’s positive spillovers and keep us from realistically mitigating its negative spillovers. I am also certain that measures which serve to dampen entrepreneurial ambition are not helpful. And I am equally certain that igniting aspiration — with appropriate education, support, role models, and encouragement — across the spectrum of society will improve our society and economy. If we want growth entrepreneurship, we will have to deal with its inequality as well.

Winning as a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

The maid-of-honor was consoling the bride, desperately trying to keep her makeup from liquefying. The yacht was perfect, of course, and most of the bridesmaids were there as planned. So what was the problem? No pictures. The photographer was a no-show. Well, the bride would make sure that he never got another high-profile job. And to think, all the best families had raved about his genius.

Two hours later, as they lay desolate on the yacht’s sun deck in the warm tropical air, they heard the roar of twin diesels. Looking up, there in the bowsprit chair of a racing boat was the photographer, Paul Barnett, snapping photos from a long telescopic lens. James Bond with a camera.

But of course! You don’t photograph the wedding party on the yacht itself; too close quarters. You shoot from a separate boat! What a genius. Everything turned out OK – spectacularly, really — in the end.

But let me tell you the story from the point-of-view of my brother Paul, the tardy but brilliant photographer: A desperate realization that he had been told the wrong time; a frantic cab ride to the marina, only to see the yacht heading out to sea; a search for a fast boat; a payoff to a nefarious bad guy; the last-second idea to shoot from the bow-sprit chair strapped in like a marlin fisherman. And then, of course, the usual self-assured act later on, as if to say, “All part of the plan.”

Some people have a way of making things go right, no matter how badly they seem to be going wrong. Why do winners seem to just keep winning?

Social scientists tell us that winners keep winning for several reasons. First off, they may just be better. Quality aside, we know that those with a reputation for past success tend to get disproportionate credit for future wins – the “Matthew effect” described by the sociologist Robert K. Merton. And of course the winners from the past tend to be in the right place to make things happen in the future, and have the connections and resources to make good on those opportunities.

But there may be another reason that winners keep winning, a reason that is particularly useful to understand business leadership: Some people tend to be unrealistically optimistic, a view that sometimes makes itself come true.

The downside of such unrealistic optimism is that it can lead you to be out of touch. But the upside is that an unrealistically optimistic outlook might trigger what’s known as a self-fulfilling prophecy (another idea pioneered by Robert K. Merton).

Social psychologists have been talking about these “positive illusions” for years in terms of mental health outcomes (see the work by Shelley Taylor and her colleagues). But when such views trigger the self-fulfilling prophecy, these illusions have the potential to increase chances of success. As my colleague Andy Rachleff argues, winning helps a leader feel confident in future contests, thereby increasing their chances of winning. Many, many people have commented on Steve Jobs’s “reality distortion field”; Jobs believed in possibilities even when others saw them as unthinkable. Of course, once he believed, then others would too, making his vision more likely to come true.

Paul Barnett could not accept that he would fail. So in a situation where others would throw up their hands and admit defeat, he kept scrambling. Not letting the facts get in the way, the unrealistic optimist expends effort as if victory was within reach, which of course makes that victory more likely. And with every victory, the optimist’s unrealistic view gets confirmed yet again.

The lesson for leadership is clear. We know that a well-informed decision is one that sees reality for what it is. But leadership is so much more than correct calculation. Especially in uncertain times, what the leader believes to be true may end up so through the self-fulfilling prophecy.

A version of this post originally appeared at www.barnetttalks.com.

Do You Need to Lighten Up or Toughen Up?

Which has helped your career more?

A. Positive Feedback

B. Negative Feedback

If you’re like most of the people we’ve recently surveyed, you answered “B.” Praise is always good to hear, but 57% preferred to hear constructive criticism. There’s no mystery why. Practically three quarters of them thought their performance would improve and their careers advance if their managers gave them corrective feedback.

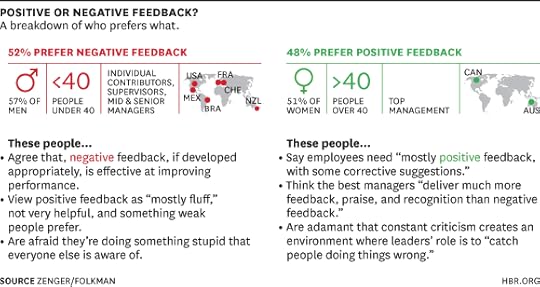

But is that so? Well, sometimes, it would appear. But sometimes not. As we continue the survey, we’ve sought additional detail, asking which kind of feedback actually has been most helpful in career advancement. (You can participate in the survey and compare your scores to the findings we’re reporting here.) Over 2,500 people have replied to this question, and it turns out that the pack is fairly evenly split on this question, with 52.5% saying negative feedback was more helpful, and 47.5% saying positive feedback helped them more.

This is something to consider if you’re managing people who fall into both camps, because they’re almost nothing alike.

We can sum up the philosophy of those who favored negative feedback as “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” A whopping 96% of them agreed with the statement “Negative feedback, if delivered appropriately, is effective at improving performance.” And most believed that negative feedback not only improves the performance of those who receive it but increases the influence of those who give it. Fully 72% of this group agreed that leaders can be most influential in their careers by “giving corrective feedback and advice when mistakes are made.” What’s more, they tended to view positive feedback as “mostly fluff,” not very helpful — and as something the weak would prefer.

All in all, many people in this group seemed to have an internal fear they may be doing something stupid that is ruining their careers — something everyone else is aware of and no one, including the boss, is willing to speak about plainly.

Those who had found positive feedback more useful as they advanced were adamant about the harmful effects of constant criticism, which they felt created a demoralized work environment in which the leaders’ role was to “catch people doing things wrong.”

Yet even those who preferred positive feedback are not suggesting that leaders should entirely abandon giving negative or corrective feedback. When ask what employees need, 75% said, “Mostly positive feedback, with some corrective suggestions.” Still, 67% said the best managers “deliver much more feedback, praise, and recognition than negative feedback.”

What prompts a person to fall into one camp or the other? Certainly, individual preference, background, temperament, and experience must play a role. But we did see some broad correlations in our data that give us food for thought.

First, we found a pretty direct, and significant, correlation between which kind of feedback a person favored and how old they were: 64% of those under 30 reported finding negative feedback most helpful, but 60% of those 50 or older preferred positive feedback. So it’s probably not surprising that 57% of relatively lower level (and presumably younger) supervisors preferred negative feedback while 53% of (older) top management favored positive feedback.

We also found that males were substantially more likely to prefer negative feedback (57%), but females were only slightly more likely to prefer positive reviews (at 51%).

Moreover, people’s assumptions about which feedback is most helpful was influenced by their functions, and not always in the way we might have expected. Sixty-six percent of people in quality assurance found negative feedback more helpful, something that might be connected with their professional focus on eliminating defects. Those in legal, operations, finance, and accounting showed a similarly strong preference for negative feedback, perhaps reflecting the importance that anticipating and addressing risk plays in their work. But if so, how to explain why those in sales also show a strong preference for negative feedback? Or that fully 60% of safety officers – arguably those most concerned with risk – favored positive feedback? Perhaps less puzzling is the fact that administrative, clerical, and HR professionals also preferred encouragement to criticism.

National culture seems to have an influence here as well. In the U.K. and the U.S., 53% prefer negative feedback. But an equal percentage in Australia and even more (56%) in Canada, prefer positive input. The countries with the strongest preference for negative feedback were Mexico, New Zealand, France, Switzerland, and Brazil, who report a 60%-plus preference for negative feedback.

Clearly, both positive and negative feedback are essential. Perhaps each works best at different times; certainly each works differently with different people. So, if you are one of those who believe the world would be a better place if people only knew what they were doing wrong, our advice to you is this: “Lighten up.” Only 12% of the people in our research reported being surprised when they received negative or corrective feedback. On the whole, apparently, people in our survey knew what they were doing wrong before anyone told them anything.

But conversely, if you are a person who strives to focus only on the positive and assumes that people don’t need corrective feedback, our advice to you is “Toughen up.” People need to understand boundaries, and they need confirmation from their leaders when they’re doing something wrong. The best leaders provide both varieties of feedback well and have learned to be insightful and selective about when to deliver which sort to which sorts of people.

Draw Your Elevator Pitch

When it comes to a good elevator pitch, brevity and memorability are everything. Most elevator pitches are neither.

One of us (Liza) is a staff cartoonist for the New Yorker, while the other (Deb) is a mentor to many start-up founders. We got to talking about the problem of crafting a brief, memorable pitch, and the impact of powerful visuals — and began discussing how any new venture or project could benefit from a pithy cartoon that sums up its value proposition. After all, most people are visual learners. And many people — Deb included — turn first to the cartoons when they get their copy of the New Yorker. So why shouldn’t entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs use that human impulse to their advantage?

We see five reasons that cartoons can convey ideas and start conversations better than traditional elevator pitches:

Cartoons force us to distill and prioritize our value proposition down to its simple essence – the real reason customers need what we’re offering. The exercise of fitting our values into a single, simple drawing forces us to question assumptions, listen to our targeted customers, and get to the fundamental benefit we’re offering. A cartoon can dramatize the benefit of our product or service from the customers’ perspective — instead of ours, as so many traditional elevator pitches do. Consider this example:

Humor is disarming. When people laugh, it’s a form of agreement and consensus, even if it’s just for a moment. Laughter brings people together and diffuses tension, allowing more open dialog. This lets us talk about the value proposition with our potential customers, and even investors. Our potential customers will probably open up more about their wants, needs, jobs-to-be-done because they can see themselves in the cartoon, which is easier to personalize than reading words. Consider another example:

Pictures evoke emotions almost instantaneously and can influence our behavior and decisions while words take a bit longer, literally. Our brains actually interpret images concurrently while text is processed linearly. This means we understand, remember and retains images (and their meaning) better than words. Some argue that this is due to the multiple areas of the brain involved in image processing versus language processing.

Pictures evoke emotions almost instantaneously and can influence our behavior and decisions while words take a bit longer, literally. Our brains actually interpret images concurrently while text is processed linearly. This means we understand, remember and retains images (and their meaning) better than words. Some argue that this is due to the multiple areas of the brain involved in image processing versus language processing.Cartoons can make A/B testing easier — and more fun. Since we quickly process the image, we can grasp the value proposition faster and perhaps assess how we’d react. Draw several different cartoons and captions to test out which ones get to the heart of the customer need and convey value in the most meaningful way. By testing, listening, and learning, we can iteratively refine our value proposition and show it in ways customers relate to.

Cartoons are memorable. Research has shown that the best remembered part of any message is the cartoon. Studies have shown that humans process images 60,000 times faster than text! No wonder we remember cartoons and they impact us. We all have cartoons we remember for various reasons — and you probably remember more cartoons than you do typical bullet-point PowerPoint presentations and now we know why: we are wired to favor images over text.

Cartoons are a powerful message to rally the troops, to get our people to buy in, support and become passionate about what our customers need. For decades, images have been used to engage people’s hearts and minds, from advertising to World War II propaganda posters to the power of images in social media. A cartoon provides a common symbol and language for people to share and reference in discussing their jobs, their tasks, their goals and their company’s purpose.

Of course cartoons won’t work for everything. We still need more elaborate reports and presentations for investor pitches, product launch roadmaps, and detailed strategic planning. Using a cartoon doesn’t replace for these, but can supplement these other formats (and prevent them from being quite so forgettable).

But in many cases, a good cartoon and a pithy caption are all we need to get potential customers to talk, investors to listen, and employees to remember. And stick figures can do; we don’t need to be artists. We just need to be able to think with clarity, concision, and discipline. That’s not easy — but that’s business.

What if a Company Maximized Jobs Over Profits?

All over Silicon Valley, venture capitalists are asking entrepreneurs “How scalable is your business model?” What they really mean is, “Can you grow without having to hire people?”

In our digital economy, value creation and job creation don’t always go together. Consider that Whatsapp just sold for $19 billion with only 55 employees. It used to be that business growth led to job growth. But as machines get smarter, labor becomes a reluctant necessity. Companies only hire as a last resort.

But what if the purpose of a company was to employ people? Instead of hiring enough people to make the greatest profit, it would make enough profit to hire the greatest number of people.

Put simply, these “job entrepreneurs” maximize jobs instead of profits. There is a precedent in this. “Social entrepreneurs” seek to maximize purpose over profits. They take a social problem, like health, poverty, or the environment, then work on finding a business model that can remedy the problem. They seek to make enough profit to make the greatest social impact.

Job entrepreneurs take a similar approach. They start with a group of people they seek to employ, then work on finding a sustainable business model that leverages their talent and experience. This isn’t about job placement. There are many organizations that help people find jobs in other companies. Job entrepreneurs bring people directly onto their own payroll.

One pioneer in the “job entrepreneur” movement is Dave Friedman. Two years ago, Friedman left his position as a Fortune 100 executive to start a new venture. His goal was to employ people on the autism spectrum – individuals who have traditionally been unemployable.

Friedman considered creating a traditional startup, but he realized that his goal was different. He didn’t want to maximize profits but rather employment. Many advised him to setup a non-profit. But Friedman didn’t want to rely on grants and donations. He believed the business needed to generate a sustainable profit to foster discipline and efficiency. He also wanted his employees to know that their jobs weren’t just charity, bringing a source of authentic empowerment.

Some advised Friedman to create a social enterprise, but the models didn’t really apply. Friedman wasn’t changing how the product was made (e.g. organic or sustainable) or where it was sold (e.g. low-income buyers). He was focused on changing who gets hired. Like social entrepreneurs, WHY mattered more than HOW MUCH. But in this case WHO mattered more than HOW or WHERE.

Without an existing model to guide him, Friedman set out to make his own. He had a powerful belief that people on the autism spectrum represent an exceptional yet hidden workforce. But he needed a business model that would turn what others saw as a deficit into a source of competitive advantage.

Friedman found his answer in what he calls “Process Execution” jobs. These are labor-intensive activities such as website maintenance, data entry, and software testing. Many companies struggle to fill these positions. But the repetitiveness and attention to detail are well-suited to the talents and abilities of people with autism.

As much as possible, Friedman downplays the fact that his employees have autism. He is not looking for charity. He wants to compete on the same playing field as other companies providing similar services. But on the inside, AutonomyWorks is unlike any of its competitors. Friedman has redesigned the way work is structured, organized, and managed to suit his employees.

With these changes, Friedman has found that not only can AutonomyWorks match traditional competitors, but it can produce better quality at a lower price. By generating profits, he is able to hire more people and fulfill his mission. In the process, he has empowered an overlooked workforce and relieved families of the costs of supporting autistic relatives.

Another company following a similar model is Shinola, a Detroit-based manufacturer originally known for its shoe polish. Shinola has recently reinvented itself to create jobs for unemployed auto workers. Like AutonomyWorks, Shinola started with jobs and worked backward to the business model. In this case, auto workers have unique skills in light manufacturing and upholstery. So Shinola produces watches, leather goods, and handcrafted bicycles. A traditional entrepreneur wouldn’t set out to make this combination of products. But for a job entrepreneur in Detroit, it makes all the sense in the world.

So what does it take to be a job maximizer?

Choose Your Talent. Who do you want to employ? AutonomyWorks focuses on people with autism. Shinola focuses on former auto workers. There are many other segments of the labor force who are underemployed or underutilized.

Find Your Market. What products or services can these workers best make or provide? This is where the entrepreneurial magic comes into play. You need to find something that suits your people and also generates a sustainable profit. Friedman recommends looking for markets where work has been off-shored or automated, and that have low capital requirements.

Design Your System. What innovations do you need to meet the unique needs and bring out the best in your workers? This might involve rethinking hiring, process design, management, or organizational culture. The key is turning people’s disadvantage in society into your company’s competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Over the last twenty years, we have successfully created an entirely new economic sector in which social entrepreneurs maximize purpose over profit. It’s time to turn this entrepreneurial spirit on a new goal: job creation. We need more people like Dave Friedman and more companies like Shinola — job maximizers and employment entrepreneurs.

The Four Keys to Being a Trusted Leader

Self-aggrandizement and even plain old greed has become standard fare in the executive cafeteria. And yet CEOs wonder why their employees and the public exhibit such a high degree of mistrust toward business and business leaders. The truth lies in the way many CEOs talk and behave.

Real leadership – the kind that inspires people to pull together and collectively achieve something great – can only be exercised when an executive is trusted. And trust arises when someone is seen acting selflessly. This may not sound like news – indeed the centuries-old concept of servant leadership is based on it. But if it also sounds vague and hard to apply to your own leadership setting, let’s break it down further. People in an organization perceive selflessness when a leader concerns him or herself with their safety; performs valuable service for them; and makes personal sacrifice for their benefit.

I still have the watch my grandfather received when he retired after 50+ years working for a trucking company as a staff accountant in western Pennsylvania. I wear it regularly. Today, of course, very few people make it to a ten or even five-year anniversary with a company – why did my grandfather stay 50? He appreciated the safety of that workplace – and despite what you might want to believe, safety is up to leaders to provide or deny. Safe is not cutting people as soon as there is a dip in the economy. Safe is not giving raises to a few executives while colleagues languish with small or non-existent increases. Safe is not producing extraordinary profits while failing to develop a clear career path and development plan for every employee. What safe is, is a place where people come to work not worried about whether they will have a job tomorrow, where compensation is fair, where employees feel that they have gotten a little bit better at their job every day, where they feel there is opportunity to advance and learn, and where their bosses treat them like they are important contributors to the betterment of the organization. Safe makes a great company.

If safety doesn’t fit well into our current performance-based business culture, then the notion of leader service fits even less. The executive mindset is to “win/perform.” Most executives that I work with love their company and want it to succeed, but very few of them think of themselves as being “in service” to those whose work must make that happen.

The service mindset is uniquely different from the performance mindset. It isn’t built by an external set of rules or process, but grows from a set of deep-rooted values that are lived minute-by-minute by leaders. One of the CEOs I work with used a visual device to signal the values he wanted to pervade the senior ranks. He inverted his Organization Chart, so that the larger group of names – the people directly serving customers – were displayed at the top of the chart. The Executive team including the CEO were shown below, signifying that their whole purpose in the organization was to support and serve that crucial, client-serving level. Not only did this help with executives’ priority-setting, it was motivating to everyone. People do better work for a CEO who they feel is working for them, too.

The idea of personal sacrifice in today’s business environment usually translates to giving up “work/life balance” by travelling a lot and working late – and certainly no one in the ranks who is doing that likes to see the boss putting in fewer hours. (Whether you believe it or not, people know when you aren’t “all in.”) But the sacrifices that matter most are the ones that involve sticking one’s neck out for a colleague or taking a stand that puts one’s political capital at risk. One CEO that I coach used to work for a mid-sized company that had been sold three times in less than two years. When the third purchaser began the integration process, the new owners wanted him to cut headcount by targeting the staff level making an average $45K/year. But the CEO suggested that the better path to profitability was to trim the executive team, and keep those lower-paid workers in place. The new owners saw the logic but took it in an unexpected direction by unceremoniously dismissing our hero. Not the best result, but he’ll be okay in the longer term. In fact, he’ll do better than ever. His sacrifice to keep others working earned him a waiting list of talent eager to work with him in his next organization.

Selflessness, Safety, Service, and Sacrifice. If finding great people to work with you is key (which it probably is) and you can’t do it all by yourself (which you can’t), then keep these concepts in the forefront of your mind. They will help you build an extraordinary team and produce winning results for your business – and when the time comes for you to retire (with a gold watch or not), you’ll be proud of how you led.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Developing Mindful Leaders for the C-Suite

Meet the Fastest Rising Executive in the Fortune 100

If President Obama Can Get Home for Dinner, Why Can’t You?

To Get Honest Feedback, Leaders Need to Ask

Women’s Unwillingness to Guess on Standardized Tests Hurts Their Scores

In an experiment, females were nearly twice as likely as males to skip test questions if they didn’t know the answers, even though the penalties for incorrect responses were so small that test-takers would have been better off answering every question, says Katherine Baldiga of The Ohio State University. The experimental test was structured like the SAT, with a point given for every correct answer, a quarter-point deducted for a wrong answer, and zero points awarded for an unanswered question (the SAT is slated to undergo structural changes in 2016). Question-skipping, which can be partly attributed to females’ greater risk aversion, resulted in significantly worse scores on the experimental test.

Developing Mindful Leaders for the C-Suite

Time Magazine recently put “The Mindfulness Revolution” on its cover, which could either be seen as hyping the latest business fad, or as signaling a major change in the thinking of executive leaders. I believe it’s the latter.

The use of mindful practices like meditation, introspection, and journaling are taking hold at such successful enterprises as Google, General Mills, Goldman Sachs, Apple, Medtronic, and Aetna, and contributing to the success of these remarkable organizations. Let’s look at a few examples:

With support from CEO Larry Page, Google’s Chade-Meng Tan, known as Google’s Jolly Good Fellow, runs hundreds of classes on meditation and has written a best-selling book, Search Inside Yourself .

General Mills, under the guidance of CEO Ken Powell, has made meditation a regular practice. Former executive Janice Marturano, who led the company’s internal classes, has left the company to launch the Institute for Mindful Leadership, which conducts executive courses in mindfulness meditation.

Goldman Sachs, which moved up 48 places in Fortune Magazine’s Best Places to Work list, was recently featured in Fortune for its mindfulness classes and practices.

At Apple, founder Steve Jobs — who was a regular meditator — used mindfulness to calm his negative energies, to focus on creating unique products, and to challenge his teams to achieve excellence.

Thanks to the vision of founder Earl Bakken, Medtronic has a meditation room that dates back to 1974 which became a symbol of the company’s commitment to creativity.

Under the leadership of CEO Mark Bertolini, Aetna has done rigorous studies of both meditation and yoga and their positive impact on employee healthcare costs.

These competitive companies understand the enormous pressure faced by their employees — from their top executives on down. They recognize the need to take more time to reflect on what’s most important in order to create ways to overcome difficult challenges. We all need to find ways to sort through myriad demands and distractions, but it’s especially important that leaders with great responsibilities gain focus and clarity in making their most important decisions, creativity in transforming their enterprises, compassion for their customers and employees, and the courage to go their own way.

Focus, clarity, creativity, compassion, and courage. These are the qualities of the mindful leaders I have worked with, taught, mentored, and interviewed. They are also the qualities that give today’s best leaders the resilience to cope with the many challenges coming their way and the resolve to sustain long-term success. The real point of leverage — which though it sounds simple, many executives never discover — is the ability to think clearly and to focus on the most important opportunities.

In his new book Focus, psychologist Dr. Daniel Goleman, the father of emotional intelligence (or EQ), provides data that supports the importance of mindfulness in focusing the mind’s cognitive abilities, linking them to qualities of the heart like compassion and courage. Dr. Goleman prescribes a framework for success that enables leaders to build clarity about where to direct their attention and that of their organizations by focusing on themselves, others, and the external world — in that order. Cultivating this type of focus requires establishing regular practices that allow your brain to fully relax and let go of the anxiousness, confusion, and pressures that can fill the day. (Editor’s note: here is Daniel Goleman’s related HBR article, The Focused Leader.)

I began meditating in 1975 after attending a Transcendental Meditation workshop with my wife Penny, and have continued the practice for the past 38 years. (In spite of this, I still do mindless things like leaving my laptop on an airplane, but I continue to work on staying in the present moment.) All of our family members meditate regularly. Our son Jeff, a successful executive in his own right, believes he would not be successful in his high-stress job were it not for daily meditation and jogging.

Meditation is not the only way to be a mindful leader. In the classes I teach at Harvard Business School, participating executives share a wide range of practices they use to calm their minds and gain clarity in their thinking. They report that the biggest derailer of their leadership is not lack of IQ or intensity, but the challenges they face in staying focused and healthy. To be equipped for the rapid-fire intensity of executive life, they cultivate daily practices that allow them to regularly renew their minds, bodies, and spirits. Among these are prayer, journaling, jogging and/or physical workouts, long walks, and in-depth discussions with their spouses and mentors.

The important thing is to have a regular introspective practice that takes you away from your daily routines and enables you to reflect on your work and your life — to really focus on what is truly important to you. By doing so, you will not only be more successful, you will be happier and more fulfilled in the long run.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Meet the Fastest Rising Executive in the Fortune 100

If President Obama Can Get Home for Dinner, Why Can’t You?

To Get Honest Feedback, Leaders Need to Ask

Don’t End Your Career With Regrets in Your Personal Life

March 7, 2014

The Importance of Giving Credit

Virtually everyone has experienced or witnessed instances in which credit was assigned in an unfair manner: managers unabashedly took credit for the work of their invisible hard-working staff; quiet performers were inadequately recognized for their contributions; credit was assigned to the wrong individuals and for the wrong things.

If a company reliably assigns credit to deserving individuals and teams, the resulting belief that the system is fair and will honestly reward contributions will encourage employees to give their utmost. On the other hand, if credit is regularly misassigned, a sort of organizational cancer emerges, and individuals and teams won’t feel the drive to deliver their best because they won’t trust anyone will recognize it if they do.

From my experiences leading teams in government, academia, clinical medicine, and the private sector, I have evolved a set of rules to help manage some of the issues with the assignment of credit. These rules are my own and don’t reflect any official policies of the organizations where I’ve worked.

Keep people honest. It is important to demand that individuals be honest about their true contributions to projects and initiatives. And their claims should be cross-checked. Individuals whose careers developed in organizations where they had to fend for themselves will often err on the side of overstating their contributions. A star performer on one team that I led was often taking more than her share of credit and it was rubbing her colleagues the wrong way. When I drilled into the root cause, I discovered it was bad behavior she learned in her previous job, where unabashed self-promotion was required to rise. Guiding her to be honest about her true contributions and to highlight the contributions of others sent a strong message about our organizational culture.

Recognize those who recognize others. In addition to verifying individual accomplishments, there is a lot of value in recognizing and highlighting cases when individuals take the time to recognize others. It sends a signal that generous and honest attribution of credit is something that the organization values. Early in one of my jobs, I took a few moments to send e-mails to thank individuals who had helped make a project of mine successful and copied my boss. My boss, in turn,scheduled time with me to thank me for taking the time to recognize others. In doing so, he sent an important message that he valued this type of behavior, and it became a habit: Ever since then, I’ve religiously sent similar e-mails to members of successful teams I’ve led.

Look out for and elevate the quiet performers. The best contributors are often the quietest. For whatever reason, they are not worried about credit and are happy to take a back seat. But people in the guts of an organization often know that some of these individuals are the lynchpins who sustain a project or unit. Taking the time to identify and reward the quiet heroes can generate good will across an organization because it creates the sense that there is real integrity.

Remember that there’s plenty of credit to go around. A mentor early in my career once told me that “credit is infinitely divisible” — in other words, there are no limits on how many individuals can be recognized for contributing to an outcome. That said, credit quickly loses meaning when everyone gets it, including people who didn’t do anything. Highly specific attributions of credit always trump blanket statements of praise. And the value of praise and credit is always higher when leaders and organizations deliver criticism with equal discipline.

Getting the assignment of credit right is important to everyone. It is a driver of high performance. It is a key to making people feel fulfilled and motivated. The very best leaders and organizations get this and spare no effort to get it right.

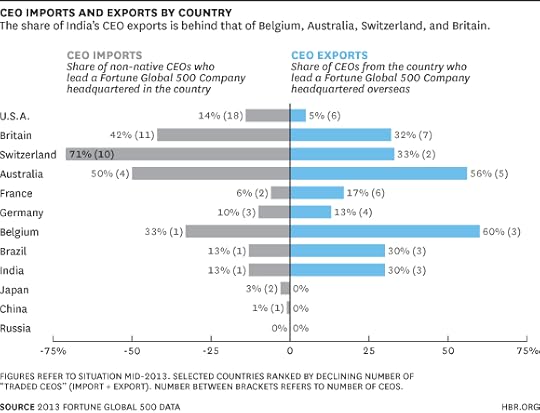

Are CEOs Really India’s Leading Export?

Satya Nadella’s appointment as Microsoft’s CEO was greeted with headlines such as “Why Microsoft and Everyone Else Loves Indian CEOs,” echoing Time’s 2011 lead heralding “India’s Leading Export: CEOs.” But have Indians really risen to the top of many of the world’s largest corporations? A systematic analysis of mid-2013 data on the world’s largest firms by revenue, the Fortune Global 500, shows that at that time only three non-Indian firms were led by Indian CEOs: Arcelor Mittal (Lakshmi Mittal), Deutsche Bank (Anshu Jain), and PepsiCo (Indra Nooyi). That was exactly the same as the number of non-Brazilian firms run by Brazilian CEOs, and short of the 5 non-South African firms led by South African CEOs.

Does the paucity of Indians at the top of non-Indian Fortune Global 500 corporations mean that the late C. K. Prahalad’s assertion that “Growing up in India is an extraordinary preparation for management” was wrong? Not necessarily. Indians have indeed gone out and achieved great managerial success abroad. The proportion of Silicon Valley tech startups led by Indians has risen from 7% in the 1980s and 1990s to at least 13% and by some estimates more than 25% (even though Indians make up less than 1% of the US population). One estimate pegged the annual income of the Indian diaspora at about one-third of India’s GDP, with much of that coming from Silicon Valley.

The real myth is not the success of Indians abroad but rather that the world’s largest firms are so global that their national origins no longer influence who they select for CEO. Only 13% of the Fortune Global 500 companies are led by CEOs who hail from outside the country where the firm’s headquarters is located. Also, the foreign countries where Indian CEOs do lead Fortune Global 500 firms are illustrative of how openness to foreign CEOs varies widely from country to country. European firms, on average, are the most likely to have foreign CEOs. U.S. firms lie in between European and Japanese firms.

Firms’ propensity to hire foreign CEOs is also highly correlated with their home countries’ general openness to trade, capital, information and people flows as measured on the Depth Index of Globalization that I compile with my IESE Business School colleague Steven A. Altman.

India’s fame as a CEO exporter must be juxtaposed against the paucity of non-Indians running major Indian corporates. After the untimely demise of Karl Slym, who briefly headed Tata Motors, none of India’s eight Fortune Global 500 firms is led by a non-Indian CEO. In fact, only three of the 112 Fortune Global 500 companies based in any of the BRIC countries are led by a non-native CEO! As firms from these countries seek to differentiate and build brands in advanced economies rather than competing mainly based on low home-country cost bases, the troubling signal this sends to foreign talent about their career prospects will become increasingly important.

Returning to Microsoft’s selection of an Indian CEO, it is interesting to note that one source estimates that more than one-third of Microsoft’s workforce is of Indian descent. Microsoft also earns about half of its revenue outside of the United States. The appointment of a non-native CEO of any origin is still an unusual occurrence, but Microsoft’s selection of an Indian was, all else equal, not entirely surprising. And it sends a very positive message to high-potentials throughout Microsoft: this is a company where the best candidate, regardless of national origin, can rise to the top.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers