Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1462

February 26, 2014

European Businesses Wake Up to the Value of an MBA Degree

At the beginning of the 2000s, the salary bump from getting an MBA in the U.S. was 50% greater than that from a European MBA, but over the subsequent decade the gap declined almost to zero as European companies began to view business degrees as highly desirable, say François Collet and Luis Vives of Ramon Llull University in Spain. One consequence has been a rise by non-U.S. institutions in business-school rankings, which are heavily dependent on post-MBA salaries. For example, in 1999, 9 out of the top 10 business schools in the Financial Times Global MBA Rankings were located in the U.S., but by 2010 the number had declined to 6.

In the Messiness of Life, What’s Fair to Employers?

If you’re interviewing for a job and pregnant, should you keep your pregnancy a secret? Or do you have an obligation to tell your prospective employer? When I posed this question on LinkedIn, about half the responses defended a woman’s right to hide her pregnancy from a potential employer. The other half insisted that employers have a right to know: withholding information is dishonest, and could potentially cause the employer great harm.

I wasn’t surprised that women admitted to hiding a pregnancy during a job interview; their comments underscored the idea that we can’t trust “The Man.” As consultant Leif Blumenau put it: “Don’t be ridiculous; who would hire someone who soon after goes on extended leave. It seems a woman has to choose between making a career and having babies.” Blumenau’s straight talk echoes what I encountered while pregnant on Wall Street. Instead of seeing it as a moment to gauge my ability to think strategically, negotiate with multiple stakeholders, and to navigate constraints, I felt like I was being asked to choose between my career and motherhood. No wonder so many women on the cusp of motherhood opt to become their own boss or to freelance.

Which makes the level of concern others expressed for the company doing the interviewing rather stunning. A representative example comes from reader Karen Jones: “If you interview when you are pregnant and you don’t advise a prospective employer, you are starting out as a liar, and that is how you should be treated.”

Certainly, the employer-employee dynamic can be complicated. Consider small business owner Anja Dalby who struggled financially when her firm hired an employee they didn’t know was five months pregnant, and the company paid one year of maternity leave in addition to hiring a replacement.

This particular case aside, with about half of my respondents worrying about what was “fair” to the company, it appears that the social contract of Henry Ford’s era is dying slowly and unevenly. We no longer want to check our dreams at the door and work only for a paycheck — we want meaning and fulfillment from our work, and autonomy over how we do it. And yet it’s hard not to pine for the sugar daddy sinecure. We still want companies to take care of us — and despite the decline in pensions, the rise in layoffs, and the flatlining of most people’s paychecks, we want to do right by our companies, too. Which is why the disruptions to our career arc — whether it’s a new baby, sick parents, or the dream of going back to school, travel, or volunteer more — can be so difficult. To jump to a new learning curve, we must leave behind the relative certainty about status, compensation, and benefits.

This then becomes a quandary. If forced to choose, you may decide your personal life takes precedence and go independent. If you don’t love your job but are wedded to its benefits, you may shelve your dreams to stay loyal to the company (or the security it represents). But either way, it feels all-or-nothing.

It may be tempting to see this as fair or even beneficial to the company — you’re all in, or all-out. And yet dilemmas like this help explain why employee engagement is so low. If it’s “you” vs. “the company,” both parties lose. By contrast, employers who who support and encourage their employees’ dreams breed loyalty, resulting in higher profitability. According to Towers Perrin, Intl., organizations with a highly engaged workforce increase operating income by 19.2%, while low engagement led to a 32.7% decline in operating profit.

Communispace, the leader in online insight communities, is an example. One of their engagement policies is a one-month sabbatical available to employees who’ve worked at the company for ten years. Employees can learn whatever they want and go wherever they want. CEO Diane Hessan was a golf novice and spent her sabbatical really learning the game; Julie Wittes Schlack, SVP of Innovation and Product Design, spent time writing a book; and Siobhan Dullea, Chief Client Officer used her time to train for her black belt. It’s no wonder that Communispace reports a 60% engagement rate vs. the national average of 30%, and has a voluntary turnover rate of just 12%, compared to an average of 25 to 30% turnover for agencies with a similar profile.

The reflex we’ve developed over the decades is to see life’s turning points, whether it is pregnancy or something else, as at odds with engagement at work. But canny managers instead use these transitions to cement ties with their employees — not to push them away.

Henry Ford’s contract may be passé, but the imperative to turn a profit is not. With the business landscape more competitive than ever, employers need people who can produce results. Who could be better qualified to do so than the person whose career is a case study in executing amidst the messiness of a life?

February 25, 2014

What Does Success Mean to You?

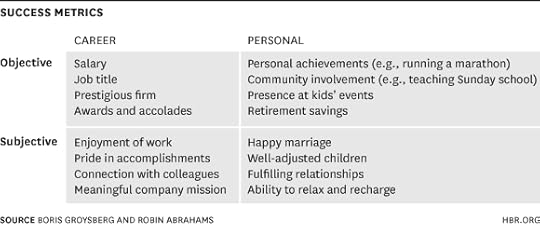

How do you know if you’re successful? Do you rely heavily on objective metrics such as your job title, the size of your bank account, or the colleges your children are getting into? Or do you focus more on the subjective, such as the satisfaction of solving thorny problems at work, the joy of collaborating with clever colleagues, or how happy you are at home?

You might not even realize where you’re placing the most emphasis until you try plotting out your success metrics in a grid like this:

Even if you find yourself listing mostly objective factors, the subjective elements have a way of tugging at you, don’t they? The relationship between the objective and the subjective is actually complicated and idiosyncratic. Subjective success is an individual’s response to an objective situation. A corporate lawyer may work for a highly respected firm and have a lavish compensation package, but if her career falls short of her dream to become a Supreme Court justice, for instance, or if practicing law seems merely a good way to make a living and doesn’t provide an intellectual buzz, she won’t feel successful.

In almost 4,000 interviews and more than 80 surveys, senior executives were asked what success means to them in work and in life (see our March HBR article “Manage Your Work, Manage Your Life”). Subjective factors such as making a difference and working with a good team in a good environment came up frequently in leaders’ definitions of career success. And rewarding relationships were by far the most common element of personal success. In fact, the executives in our research sample have discovered pretty universally that keeping a high-powered career and a family on track means allocating their energy and time wisely rather than grabbing at every possible brass ring. In other words, if your definition of success is just a laundry list of objective rewards, it may not be all that realistic — or as satisfying as you’d imagine.

As we note in our article, no one would head up a major business initiative without establishing clear metrics for success, based on a strong vision of what a “win” will look like. The same principle should apply to managing your life and career. Life is too short to spend valuable energy chasing after objective success measures that don’t affect your subjective bottom line. Just as you’d do on the job, make your professional and personal “wins” clear, meaningful, and achievable to ensure the maximum emotional return on your investment of effort.

Here’s one final question we’d like you to think about: Have you ever had a “win” that should have been meaningful but left you feeling dissatisfied and empty? If so, share your story in the comments below. In a future post, we’ll examine the reasons that an objective accomplishment can fail to translate into subjective satisfaction.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

How to Thrive While Leading a Family Business

The “Older” Entrepreneur’s Secret Weapon

Why One Executive Quit Business Travel Cold Turkey

Walk Your Way to More Effective Leadership

The Surprising Power of Impulse Control

Against the backdrop of a declining and temptation-filled Roman Empire, Augustine hesitantly prayed for impulse control: “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.”

More recently, against the backdrop of marshmallow tests and America’s “culture of entitlement and instant gratification,” Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfeld reexamine impulse control in a new best-selling book and in The New York Times. For them, it’s a success “driver” of better academic performance, higher SAT scores, and upward mobility, and helps explain why certain groups “are doing strikingly better than Americans overall.”

It’s a provocative argument, and I expect business practitioners will be tempted to translate the insights into their professional lives. What does impulse control look like in the workplace? Can better impulse control buffer against the proven perils of multitasking, like slower and shallower thinking, lower creativity, and increased anxiety?

For some insight into these questions, I gathered a sample of personal experiments from entrepreneurs and employees who’ve made an intentional effort at impulse control by using the Pomodoro Technique. For the uninitiated, Pomodoro is a variation on batch processing. It involves setting a timer to 25 minutes and working steadfastly on a single task (or single batch of work, like email) for the full 25 minutes— thus quelling urges to multi-task and mind-wander. At the end of this work interval, users get up and walk around for a 5 minutes to rest and recharge.

An old-fashioned kitchen timer, such as the kind resembling a tomato (or “pomodoro” in Italian) will work. However, many in the sample prefer desktop and mobile apps. Focus Booster is more helpful if you like visual cues on your progress, for example, while Pomodairo is better for those motivated by personal data, as it tracks how many 30 minute sessions (each called a “pomodoro”) they completed by day, week, and project.

In my sample, experimenters initially assumed that better impulse control would result in at least one of three things: improved productivity, reduced technology-induced distraction, and a more reliable work process. However, as they put the technique to the test, initial expectations were regularly exceeded, showing that impulse control can be a surprisingly powerful pathway to self-discovery in the following ways:

Experiencing the Paradox of Control. Experimenters often start using the Pomodoro Technique to boost productivity and determine it works. “I could see a sudden improvement,” notes Jarno, whose measurements showed that he was developing code at two to two-and-a-half times his previous rate.

But they are surprised to learn that more output is not the most satisfying outcome at the end of the day. Experimenters tend to perceive quantifiable outcomes as less significant than existential ones, such as enhanced feelings of power and control. “What was way more important to me [than productivity] was that it changed the way it felt to start concentrating on hard tasks…and to tackle difficult projects,” Jarno concludes, echoing an insight I see again and again from these personal experiments.

“I felt like I was in control now. Which is kind of ironic as my day had been divided into these forced time slots,” he says.

Discovering the Root Cause of Distraction. In adopting an impulse control technique like Pomodoro, you’ll want to take steps to turn off potential technology distractions like email alerts, desktop Twitter feeds, and text messages.

Nevertheless, the real power of Pomodoro goes far beyond these familiar pop-ups, dings, and buzzes. Adopters often discover that technology accounts for only a fraction of interruptions overall, and that most interruptions originate in their unruly minds.

By batching work into tight 25-minute packages, individuals create a context for recognizing internal interruptions and for developing personalized strategies to minimizing them. During his experiment, a consultant named Magnus reports, “I quickly noticed a change in how I dealt with internal interruptions. When I found my mind-shifting to other things, searching the web…or looking up the lunch menu, I realized off the top of my head that it was a non-task.”

Tapping the power of delayed gratification, Melanie, a teacher, observes the technique “helped me keep internal distractions under control. Knowing that I could do what I wanted after a solid period of work helped me not to give in to the temptation to web surf before doing what needed done.”

Sorting What You Love From What You Hate. The initial goal for most Pomodoro experimenters is obvious: to boost resistance to digital distractions while allowing them to methodically allocate time to tasks. “The general idea is to systematically adjust the way I work,” says Sam, a writer and consultant, before he began testing the approach.

But adopters are frequently surprised to learn that each 25-minute session provides a temporal lens on what they really think about certain types of work. For work they love or value, it can be difficult to stop for a 5 minute break after “just” 25 minutes. For Warner, the ringing end to a 25 minute interval of writing code brings on the realization that this sort of work induces a state of flow. He discovered that the 5-minute break “breaks his groove.”

By contrast, others learn the technique is particularly effective at helping them complete work they dread doing. “I…use Pomodoro to help me get through the tasks I really don’t want to do — it’s a lot easier to make yourself do something when you know you only have to dedicate 25 minutes to it,” quips Lisa, a web designer.

The last 40 years of impulse control research have focused mainly on what’s quantifiable — not just on how it effects things like test scores, but also on its physiological and cognitive basis. For instance, in a recent follow-up study of original Stanford marshmallow test participants, researchers used brain scans to investigate impulse control’s biological basis.

This focus on measurement is certainly important in science and business. But as the experiences of Pomodoro adopters suggests, there’s more to impulse control than just numbers and enhanced productivity; meaning, it seems, can matter more than metrics.

How To Say “This Is Crap” In Different Cultures

I had been holed up for six hours in a dark conference room with 12 managers. It was a group-coaching day and each executive had 30 minutes to describe in detail a cross-cultural challenge she was experiencing at work and to get feedback and suggestions from the others at the table.

It was Willem’s turn, one of the Dutch participants, who recounted an uncomfortable snafu when working with Asian clients. “How can I fix this relationship?” Willem asked his group of international peers.

Maarten, the other Dutch participant who knew Willem well, jumped in with his perspective. “You are inflexible and can be socially ill-at-ease. That makes it difficult for you to communicate with your team,” he asserted. As Willem listened, I could see his ears turning red (with embarrassment or anger? I wasn’t sure) but that didn’t seem to bother Maarten, who calmly continued to assess Willem’s weaknesses in front of the entire group. Meanwhile, the other participants — all Americans, British and Asians — awkwardly stared at their feet.

That evening, we had a group dinner at a cozy restaurant. Entering a little after the others, I was startled to see Willem and Maarten sitting together, eating peanuts, drinking champagne, and laughing like old friends. They waved me over, and it seemed appropriate to comment, “I’m glad to see you together. I was afraid you might not be speaking to each other after the feedback session this afternoon.”

Willem, with a look of surprise, reflected, “Of course, I didn’t enjoy hearing those things about myself. It doesn’t feel good to hear what I have done poorly. But I so much appreciated that Maarten would be transparent enough to give me that feedback honestly. Feedback like that is a gift. Thanks for that, Maarten” he added with an appreciative smile.

I thought to myself, “This Dutch culture is . . . well . . . different from my own.”

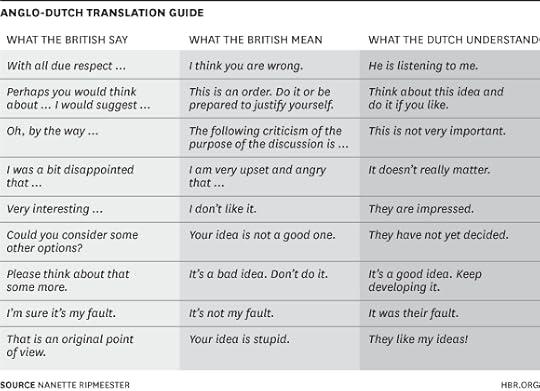

Managers in different parts of the world are conditioned to give feedback in drastically different ways. The Chinese manager learns never to criticize a colleague openly or in front of others, while the Dutch manager learns always to be honest and to give the message straight. Americans are trained to wrap positive messages around negative ones, while the French are trained to criticize passionately and provide positive feedback sparingly.

One way to begin gauging how a culture handles negative feedback is by listening to the types of words people use. More direct cultures tend to use what linguists call upgraders, words preceding or following negative feedback that make it feel stronger, such as absolutely, totally, or strongly: “This is absolutely inappropriate,” or “This is totally unprofessional.”

By contrast, more indirect cultures use more downgraders, words that soften the criticism, such as kind of, sort of, a little, a bit, maybe, and slightly. Another type of downgrader is a deliberate understatement, such as “We are not quite there yet” when you really mean “This is nowhere close to complete.” The British are masters at it. The “Anglo-Dutch Translation Guide”, which has been circulating in various versions on the Internet, illustrates the miscommunication that can result.

Germans are rather like the Dutch in respect of directness and interpret British understatement very similarly. Marcus Klopfer, a German client, described to me how a misunderstanding with his British boss almost cost him his job:

In Germany, we typically use strong words when complaining or criticizing in order to make sure the message registers clearly and honestly. Of course, we assume others will do the same. My British boss during a one-on-one “suggested that I think about” doing something differently. So I took his suggestion: I thought about it, and decided not to do it. Little did I know that his phrase was supposed to be interpreted as “change your behavior right away or else.” And I can tell you I was pretty surprised when my boss called me into his office to chew me out for insubordination!

I learned to ignore all of the soft words surrounding the message when listening to my British teammates. Of course, the other lesson was to consider how my British staff might interpret my messages, which I had been delivering as “purely” as possible with no softeners whatsoever. I realize now that when I give feedback in my German way, I may actually use words that make the message sound as strong as possible without thinking much about it. I’ve been surrounded by this “pure” negative feedback since I was a child.

All this can be interesting, surprising, and sometimes downright painful, when you are leading a global team: as you Skype with your employees in different cultures, your words will be magnified or minimized significantly based on your listener’s cultural context So you have to work to understand how your own way of giving feedback is viewed in other cultures. As Klopfer reported:

Now that I better understand these cultural tendencies, I … soften the message when working with cultures less direct than my own. I start by sprinkling the ground with a few light positive comments and words of appreciation. Then I ease into the feedback with “a few small suggestions.” As I’m giving the feed- back, I add words like “minor” or “possibly.” Then I wrap up by stating that “This is just my opinion, for whatever it is worth,” and “You can take it or leave it.” The elaborate dance is quite humorous from a German’s point of view … but it certainly gets [the] desired results!

What about you? Where do you think your own culture falls in this regard? If I need to tell you your work is total crap, how would you like me to deliver the message?

Founding a Company Doesn’t Have to be a Big Career Risk

“I’m so glad we read that case — I’m NEVER going to start a company.”

That was the general consensus after one of my favorite HBS classes: an entrepreneurship case on a company called Tickle. After five years, in 2004, Tickle was profitable with more than $20 million in revenue; it received an acquisition offer for $100 million, as well as IPO entreaties. But the company had almost failed several times, and even success was brutal.

This case reminded me of my time as a founder, and recalled a question I’ve pondered for years: given that any venture is likely to fail and certain to be emotionally difficult, how can we minimize our risk when starting a company?

I define risk as the probability of an unacceptable outcome, which is easiest to see in financial terms, since starting a company comes at the expense of pursuing more stable and better-paying employment. The financial risk of a career in entrepreneurship is the chance of spending 20 years in startups with nothing to show for it — neither money nor an impact on the world.

Develop deep expertise — your best risk-mitigation strategy

The most important way to mitigate risk is to become excellent at either engineering, product, selling, or operations and management. If you excel in one of these areas, you can always get a well-paying job doing interesting work — at startups or established firms. In financial terms, focuses expertise is a call option on other careers, and it increases your chance of startup success, to boot.

Developing focused expertise can be a challenge when you’re starting a company: a founder has to do some of everything, but the role of startup CEO is not nearly as transferrable a skill as domain expertise, since your employability strongly depends on your company’s success (in which case, you won’t need the job).

One option is to build expertise before founding a company: ask VCs and others in the startup community to recommend the most competent people they know — heads of engineering, sales, product, and operations — and look for a job working directly under them. This requires balancing your level of experience with the maturity of companies you approach: the goal is to find boss-mentors who have learned by building a team before but who aren’t so senior you can’t get direct mentorship.

Alternatively, if you’re committed to founding a company immediately, pick an area of specialization up front and craft your job to emphasize that domain. Find a couple of mentors outside your company (from the same group mentioned above), who are willing to spend time with you every month, and focus on both individual performance and processes to manage your domain. Usually, startup success means hiring a “professional CEO,” so domain expertise also means you have the option of staying on at your company and learning the CEO ropes.

Other risk-mitigation strategies

While developing expertise is the most certain way to reduce entrepreneurial risk, many other strategies exist:

Process — Using the right processes to deal with market uncertainty (e.g. Lean Product Development and Customer Development processes) decreases the chance of a startup’s failure.

Serial diversification — By working on many startups over time, you gain the benefits of diversification. If each company you start only has a 20% chance of success, and you start eight companies over a career, your total chance of success is 85%.

Resource value — Your company’s downside is determined by the value of the resources you build. Thus, companies with great engineering talent have the “acqui-hire” option – they have created value by assembling great teams. Similarly, Nest was able to build a network of connected devices that provided both established customers and data that was valuable to Google. If the value of the resources you are assembling exceeds what they cost to assemble, even failing to achieve your vision can pay (Clay Christensen describes the difference between resource- and business model-based acquisitions here).

Equity — When given the chance, take some money off the table.

Help people out — Looking for opportunities to help other people can help build connections that can prove useful later on, whatever the outcome of your company (Adam Grant describes the power of generosity in Give and Take).

Don’t be financially stupid — Don’t use your life savings, mortgage your home, or pay on credit cards to start a company.

With all of these options to reduce the risk of starting a company, being a career entrepreneur is actually less risky than you think. And if you care about having an impact — doing things that wouldn’t get done without you — entrepreneurship may be less risky than alternatives we often characterize as “low-risk.”

But financial risk only explains part of why Tickle turned so may people off to the idea of entrepreneurship. The expectation of emotional difficulty magnified the feeling of risk: a 20% chance of success, and a 100% chance of emotional strife makes entrepreneurship feel riskier. To this problem, there is a simple solution: if your mission isn’t worth suffering for, then don’t bother. Only start something that matters; then you can look back, satisfied, whatever the outcome.

What Do People Have Against Retirement Income?

Over the past few years, economists have expended a lot of time and energy attempting to explain what they call “the annuity puzzle.” The puzzle is this: A guaranteed lifetime income is a valuable thing (especially if it comes with regular cost-of-living adjustments), and people who receive one through a traditional state or corporate pension are generally very happy with it. So why is it that those with the self-directed “defined contribution” retirement plans that have become standard in the U.S. — 401(k)s, 403(b)s, IRAs, and the like — so rarely convert the money they’ve saved into pension-like life annuities that guarantee a monthly check until they die?

Part of the explanation is that only 6% of corporate 401(k) plans even offer an annuity option at retirement (you instead have to roll the money over into an IRA and then shop for an annuity). But even among those with traditional defined-benefit pensions that offer a choice between a lifetime income and a lump sum, the majority chooses the lump sum. And new research from economists Daniel G. Goldstein, Hal E. Hershfield, and Shlomo Benartzi seems to indicate that most of these people don’t fully understand the choice they’re making.

As a big fan of the all-annuity Dutch retirement system, generally considered the world’s best, I tend to read such findings and harrumph in dismay. A couple of years ago I was invited to speak about “Investment Advice in a Turbulent Economy” at a college reunion. Everybody else on my panel was a money manager with tips on what to buy; I instead subjected my fellow alumni to a harangue about how ridiculous it was that American retirees had to spend so much time thinking about their investments, and how much better off most people would be with lifetime annuities. I think the audience appreciated that I at least had something different to say, but I could also see eyes glazing over every time I said the word “annuity.”

I don’t really know how to undo the narcotic properties of the letters A-N-N-U-I-T-Y. But rather than launching straight into another harangue, I thought it might be helpful to run the annuity puzzle by someone with a lot of hands-on experience, Harvard Business School senior lecturer Bob Pozen. Over the past four decades, Pozen has seen the U.S. retirement-savings system from the perspective of SEC lawyer, top executive at two giant mutual fund companies, Social Security reform commission member, and not-really-retired retiree. “It is interesting,” Pozen says. “Almost every economist you ever speak to says that’s what you want to do — have your money in a life annuity with survivorship benefits. But no one ever wants to do that.”

This unwillingness isn’t entirely a puzzle, though. Here, with an assist from Pozen, are the main pros and cons of annuitizing retirement income:

The big advantage for the individual is that you don’t run out of money before you die, which lots of Baby Boomers are currently on track to do. The downside is that you’re locked in. If all your money is in a life annuity, you can’t leave any to your grandchildren and you may not have enough cushion to deal with unexpected medical bills. “People want optionality,” Pozen says. Also, there’s always the risk that your annuity provider will fail to pay up — which is mitigated in the U.S. by pension and insurance backstop funds, but certainly isn’t zero. Just ask the current and retired city employees of Detroit.

For society, the attraction of a fully annuitized system is that it’s much cheaper than having every last person save up and manage her retirement money on her own. An individual retirement saver who doesn’t want to risk going broke at age 95 needs to put aside a lot more money than a pension plan or insurance company has to in order to guarantee somebody a lifetime income. That’s because, in a life-annuity system, those who die in their 60s end up subsidizing those who live to 95. It’s sort of the opposite of what happens in health insurance, where the healthy subsidize the sickly. The downside with retirement annuities is distributional — the affluent are healthier and live longer than the poor. Pozen points out that this life-expectancy gap already nullifies much of the progressivity built into Social Security, and will probably grow larger in coming years.

Still, even Pozen thinks the economists are right that Americans ought to be annuitizing more of their retirement savings. One key, he thinks, is making annuitization less of an all-or-nothing choice. This argument is backed up by recent research by economists John Beshears, James J. Choi, David Laibson, Brigitte C. Madrian, and Stephen Zeldes, who found that people are much more amenable to annuitizating part of their retirement savings rather than all of it (something that the IRS is currently proposing to make easier for pension plans to offer). Pozen also suggests that the best kind of annuity for most people might be a deferred one that you buy at age 65 but doesn’t start providing income until age 80. “People usually have a good idea when they retire at 65 what’s going to happen for next 10 or 15 years,” he says. “But they have no idea if you go further out.” A deferred annuity amounts to relatively cheap insurance against what might happen “further out.”

Such products exist — they’re called Advanced Life Deferred Annuities — but I don’t get the sense that they’re common or easy to find or understand. The private annuities market in general is maddeningly complex, and the products that get pushed the hardest by insurers are often a bad deal for consumers. The oft-criticized variable annuities are the worst offenders, but even in fixed annuities the focus all seems to be on products that aren’t indexed for inflation — and thus don’t really insure that you’ll have enough money when you’re 90. Then again, this is partly because the insurance companies are operating at an information disadvantage of their own: The people who buy annuities, especially inflation-linked ones, tend to have good reason to believe that they’re going to live a long time. And those who don’t buy them often have good reason to suspect they won’t be around all that long.

This is what’s called an adverse selection problem, similar to the one that motivated the individual mandate in Obamacare. So does the U.S. need a retirement-annuity mandate? Well, we actually already have a partial one, and it’s called Social Security. This aspect of Social Security has in the past been cause for complaint. “Compulsory purchase of annuities has … imposed large costs for little gain,” economist Milton Friedman argued back in 1962. “It has deprived all of us of control over a sizable fraction of our income, requiring us to devote it to a particular purpose, purchase of a retirement annuity, in a particular way, by buying it from a government concern.” In a world beset by annuity puzzles, though, Social Security’s structure makes a lot more sense. “The most important annuitization we have is Social Security,” Pozen says. “So we ought to make sure we really have it.”

The sustainability of Social Security is a topic for another day. When it comes to annuity puzzles, though, there’s one more factor worth mentioning. In the Palliser novels of Anthony Trollope, which have constituted most of my bedtime reading for the past month, there’s endless discussion of how much money people have. These 19th century fortunes, however, are almost always described in terms of the annual income they produce, not the lump sum.

Hardly anybody talks about investments that way now. Part of it is just that most of us expect to live from our jobs, not the inherited wealth still so crucial in Trollope’s world (and even more so in Jane Austen’s half a century earlier) — so whatever fortune we may have built or inherited isn’t expected to produce income just yet. But I also wonder if asset values have come to play such a big role in modern economic life that we’ve forgotten what those assets are for. In countless ways, financial discourse in the Western world in general and the U.S. in particular has shifted from a focus on income to a focus on assets or net worth. CEOs and financial-sector stars make the vast majority of their money in asset-price-linked jackpots, not annual paychecks. Accounting has moved from a basis in history and income to one in which prices are marked to market. Investors once bought stocks purely for the dividends; now dividends are usually an afterthought, with price appreciation the main goal.

In an apparent attempt to buck that trend, the Labor Department is considering a new rule for providers of 401(k)s, IRAs, and other retirement accounts that would “require a participant’s accrued benefits to be expressed on his pension benefit statement as an estimated lifetime stream of payments, in addition to being presented as an account balance.” A similar bill has been floating around Congress (but not really making any progress) for the past couple of years. It might seem like a petty little requirement. But maybe it’s a petty little requirement we need.

Office Politics: A Skill Women Should Lean Into

Who says women don’t like office politics? Just about everyone: My clients. My colleagues. My mother. The sommelier at the French restaurant I ate lunch at last weekend. They’ve all complained about office politics. Some women claim they are not good at it, while others simply avoid certain hot-button business situations because they think playing politics is “sleazy.”

Need more evidence? In 2013, my partners and I conducted a combination of surveys and interviews with over 270 female managers in Fortune 500 organizations to determine what they liked and disliked about business meetings, and one of the things that repeatedly fell into the dislike column was politics. In the process of coaching and training women leaders over the course of a decade, we’ve maintained a running list of common threads—and a disdain of office politics is in the top three. In reviewing several thousand 360-degree feedback surveys we found that both women and their managers cite political savvy as an ongoing development need for women.

But, as Winston Churchill once said, when you mix people and power, you get politics. Politics is a big, messy issue encompassing everything managers deal with all the livelong day. And it’s not just a sprawling topic; it’s also a pivotal one for women, because backing off in political situations makes it impossible for them to succeed in the highest levels of leadership.

With that in mind, we put together a prescriptive model suggesting several ways women can improve their political performance, which we’ve used with success in recent coaching seminars. Here’s what it looks like:

Plug In: Today’s nonstop pace causes some of us to go it alone—working through the week’s agenda simply to stay afloat. Politically speaking, operating in “survival mode” can leave us isolated. Consider this entry from a 360-degree performance report we reviewed: “Her direct reports like her and she’s the best at serving clients. However, she’s always out in the field. I’m not even sure she knows the names of all the senior leaders in her office. This is a major liability in terms of her upward mobility.” When we say “plug in,” we mean forge internal alliances and tap into the grapevine (both the formal and informal networks) in the workplace. Even if you are a high performer at your job, if you are perpetually absent from the office you are missing opportunities to connect with the culture and stay attuned to the political context of your work environment.

Look Out: Imagine your career two to three moves ahead of where you are now and keep that image in your mind. Many women we work with are tightly focused on being perfect performers in the moment and don’t think enough about positioning themselves to reach the next level in their careers. Projecting out into the future helps keep you alert and allows you to be nimble when opportunities arise.

Line Up: In order to make office politics more palatable, we coach women to build their careers as if they were running for office. That means actively lining up a coalition of supporters – allies, advocates, mentors, and sponsors. You need to recruit people who are willing to expend political capital on your behalf. Research indicates that men are more willing to trade favors than women are, and that may put them in a better position to line up sponsorship. Yet, even without cultivating a greater appreciation for the quid pro quo mind-set, one thing that women can do right now is to reach out and align themselves with other women who are higher up in their organization. It is not that men don’t help women, because they certainly do. But there is something to be said for connecting with the other like-minded women around you.

Act Powerfully: Executive presence is important in politics, and women need to manage theirs deliberately rather than let other people draw their own conclusions. As a thought exercise, we ask women to consider how they “land on” people — that is, what impression they make. It is a distinctive phrase that helps them remember to work proactively at making a strong positive impact. We also coach them to use “muscular” language – and what we mean here is to use non-generic language, which will have a bigger impact on your audience. Don’t just say: “That’s interesting data,” for instance. Anyone can say that. Instead, say “That’s robust data that supports my argument that …” This may sound like semantics, but saying something specific and distinctive allows you to own your ideas and control the conversation.

Get Out: Speak up and actually ask for assignments, opportunities, perks, and promotions. In the process, don’t handicap yourself. For example, saying “I’m not good at politics” is a type of self-handicapping. As soon as you say it, you diminish your power and put yourself in a position of having to overcome an obstacle you’ve put in your own way.

Take Credit: Don’t be afraid to be noticed. Politics requires you to sell yourself; yet women work harder at modesty than men. Why? Self-preservation. According to Alice Eagly and Linda Carli in Through the Labyrinth, research shows that people accept boastfulness in men but often dislike boastful women. So every woman has a choice to make: Do you want to be universally liked or do you want to get promoted? We suggest the latter. Take credit for your work. One sure way to get passed over for a promotion is to remain silent about your accomplishments and allow others to take credit.

It’s not possible to opt out of office politics. If you want to have a voice, if you want to make an impact, if you want to have a career, politics is simply part of the job.

Case Study: Can a Volunteer-Based Company Grow?

The map projected on the screen had a dot for every location where a BrainGame volunteer lived. Lena Klug, the CEO, was proud of the company’s global reach. There was even a dot in Samoa—a long way from the company’s Berlin office.

Now four years old, BrainGame had started small. Its founder, Hans Faust, couldn’t afford to hire developers at the outset, so he’d enlisted volunteers to help design, build, test, and debug the new kind of online game he wanted to bring to the world. Many people were willing to work for free because they believed in his mission: to create positive, nonviolent, commercially viable products that reward empathy and caring rather than aggression and revenge.

(Editor’s Note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.)

Klaus Hoch, BrainGame’s director of community and the person responsible for keeping the company’s thousands of volunteers engaged and happy, was giving his monthly update to Lena and the other top executives. He rattled off an impressive list of numbers detailing how many issues had been surfaced, bugs fixed, and new game versions created.

“You forgot one important figure, Klaus,” Rutger Ekberg, the head of product development, said with a smile. “More than a thousand crappy ideas proposed.”

Everyone laughed. As important as the volunteers were to BrainGame, they were an opinionated group and weren’t always easy to manage.

“That’s not exactly fair,” Klaus said once the laughter had died down. “Some of our best product ideas came from this group of—”

Klara Eberhart, the head of engineering, interrupted. “Yes, we all know that the idea for QuestFinder came from Henri, our star volunteer in Nice, but it took a lot of refinement—internal and external—to get it to where it is today. And our biggest hits, Bot Force and Living Colony, both came from in-house brainstorming and development,” she said. After a pause, she added, “Maybe it’s time we grew up and brought in some real developers.”

Klaus and Klara had been butting heads over this issue for some time, so Lena wasn’t surprised when the community director immediately spoke up.

“We have real developers,” Klaus said sharply. Indeed, the company had hired a small group of them in the past two years. “But why pay for more staff when we have thousands of people willing to do the work at no cost? Besides, this is what our business model is based on. We’re not just a company, we’re a movement,” he said, pointing to the map on the screen.

Klara wouldn’t let it go. “I know I say this all the time, but just because that’s been our model up to this point doesn’t mean it has to be going forward,” she said. “There’s too much risk in it.”

“And inefficiency,” Rutger chimed in. He explained that his team was spending close to half its time responding to volunteers’ new game proposals. “And none of them are good. In fact, we haven’t been able to turn one idea from a volunteer into a viable product since our first year. We’re wasting our time with them.”

Hiring more developers wasn’t out of the question. The company’s revenue from ad sales had jumped in the past year, so it had some cash on hand. And new investors were starting to show interest following the release of a highly praised game.

“This is not the time to move away from our roots,” Klaus argued. “We should be investing in our volunteers, not turning our backs on them. They’re our biggest enthusiasts. We’ve barely spent anything on marketing, because they do it all for us.” Instead of having traditional product launches, BrainGame always just released its latest game to its volunteers and let them promote it to their networks, and the viral approach had worked brilliantly so far. “Our success depends on keeping these people happy. And some of them are already upset over the new rules about logging fixes. They think we’re starting to act like all the other companies. We need to double down on our efforts to engage and motivate them.” Klaus folded his arms, but Klara wasn’t done.

“They’re disgruntled because their expectations are too high,” she said. “We need to bring in people whose expectations we can manage.” She proposed hiring 15 to 20 new engineers. “When we release the next two games, investors are going to come knocking on our door, and amateur hour won’t cut it any more.”

“Investors are already knocking,” Lena said, trying to refocus the conversation. She explained that BrainGame’s current backers had been asking about growth plans, and Lena was pitching new groups for a new round of financing in two weeks. “Everyone’s wondering how we’re going to scale. The numbers are all there. We’ve got a good pitch, but we need to sort out our story. Are we going to stick with volunteers? Or are we going to bring in some hired guns to help us grow?”

Too Many Risks

Klara caught Lena’s arm on the way out of the meeting.

“Want to go over to the Five Elephants?” she asked, referring to a coffee shop just a few blocks from the office. The two women had worked together at another tech start-up before joining BrainGame, and they often ducked out together for lattes.

As they made their way through the narrow Kreuzberg streets, Klara brought up the discussion they’d just had. “There are too many risks in relying so heavily on volunteers—what if a game fails because we trusted a fix to the crowd? How do we explain that to an angry investor? We need to bring in people we can count on and manage. You see my point, right?”

“Yes, of course I do,” Lena said. “But I also wonder if we’re being too German about this. Insisting on precision may not get us where we want to go. Maybe a slightly messier process could work in the long term. It’s worked until now.”

“Rutger’s concerned too, and he’s Swedish.” Both women laughed. BrainGame’s employees came from more than 10 different countries—they were as diverse as the volunteers—and everyone enjoyed poking fun at their cultural differences.

“But seriously, hiring decisions say more about a company than anything else,” Klara said. “We want to show that we’re for real, that we can afford to bring in the right talent.”

At the coffee shop, they ordered their drinks and sat down at a corner table. Klara kept talking, explaining how hard it was to work with the volunteers—many of them would work only on certain projects, and none could be held to deadlines or deliverables. Lena had heard it all before, but she listened patiently. “Project management is a nightmare,” Klara went on. “I don’t know how we’re expected to manage people when their only job description is ‘Be yourself and do what you want.’

“We can’t play the role of idealistic underdog forever.”

Thousands of Brand Evangelists

When the women arrived back at the office, Andrew Maslin, BrainGame’s head of marketing, was waiting for them in the lobby.

“I heard you went out together, and I figured Klara was going to make her case—so I want to make mine,” he said.

“We would’ve gotten you a latte if we’d known,” Lena teased.

The three of them got into the elevator. The old factory building still had original freight elevators that had to be closed by hand.

“Klaus is right,” Andrew said. “It would be a huge mistake to turn our back on the community. We’ve got thousands of brand evangelists. If we kick them to the curb, we’re going to be left with thousands of brand haters.”

He paused to open the elevator door, and then continued.

“Our story is perfect now: Small company takes on the gaming industry, fueled by the hard work of people who care about the cause. But if we start hiring hotshot developers, you’d better believe the media will change that narrative. It’ll be: Gaming company that pushes empathy shows little for the volunteers who got it where it is today.”

“Enough, enough,” Klara said, plopping down on the couch in the reception area. “It’s not like we’re going to banish them from working with us. We’re just bringing in people who actually know what they’re doing and paying them.”

“Do we want people to build our games because they get paid to, or because they love what we do and support our mission?” Andrew asked, looking to Lena for a response.

“I agree that the all-volunteer ethos makes a great story for the press, Andrew. But does it make a great company?”

Too Many Headaches?

Later that day Guy Renou, BrainGame’s CFO, sat down in Lena’s office. They had blocked off two hours to get ready for the upcoming investor pitch.

“First things first,” he said. “What’s our story?”

Lena put her head in her hands. “Everyone’s got an opinion. Klara and Rutger, of course, think we should be an execution-focused company that hires the best and brightest engineers. Klaus and Andrew are pushing the cause-driven company that has a slew of evangelists working on and promoting the products. I think I’m closer to Klaus and Andrew on this, but when I think about the pitch, I wonder if we’re going to be taken seriously if we rely so heavily on volunteer developers.”

“You know me,” Guy replied. “I love the idea of not paying for full-time developers. We’ve saved a ton of money by avoiding them. But it’s not like Klaus and his team work for free; managing the volunteers and keeping them happy costs money. Plus, think about the surprises. Let’s not forget the trouble in year two when they stopped working in protest over the new bug-reporting system. That almost did us in.”

“Right. I can’t decide whether Klaus has drunk his own Kool-Aid or whether he’s right that this is a movement. Is it even possible to lead a movement?”

Guy shook his head. “Last I checked, movements didn’t have a CEO or CFO.”

“What happens to the balance sheet if we bring in paid developers?” Lena asked.

“We can afford to hire 10 or 15 now, and more if we get this next round of funds,” Guy said. “But that’s assuming Klaus’s army doesn’t get angry and stage another revolt. If our volunteers feel they’re being usurped and leave us, it would take hundreds of paid engineers to replace them.”

“What about the investors?” she asked.

“I think the current ones like the idea of supporting a company that will change the world with the help of volunteers. But we’ve got to think about what future investors want as well.”

Guy paused for a moment, as he often did, to collect his thoughts. “It really comes down to the kind of company you want BrainGame to be, Lena.”

“I know that,” she said impatiently. “I took over for Hans because I believed in his vision.”

“But was this his vision? I was here with him when he started. Yes, he wanted to revolutionize the gaming industry, but he opted for volunteers mainly because he needed a cheap way to start.”

Lena knew this to be true. When Hans left to focus on another start-up, he told her he wasn’t sure how far the existing model would get them. Still, it was core to the company’s identity, and although it wasn’t always elegant, it had worked well so far.

“So back to my first question,” Guy said. “What’s our story?”

Question: Should BrainGame grow using its volunteer model or bring in paid developers?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

Workers Would Lose Serious Money if Employers Paid 401(k) Contributions Once a Year

A worker who started out earning $40,000 and switched jobs seven times over the course of a 40-year career would lose $47,000 in lifetime retirement savings if all of her employers followed IBM’s example and paid 401(k) retirement contributions as lump sums on the last day of each year, according to a simulation performed for The New York Times. The reason: She would lose significant employer contributions to her retirement savings in the years when she switched jobs. Only a small percentage of companies have adopted “last day rules” on 401(k) contributions, but the number is expected to rise as companies look for new ways to save money.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers