Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1466

February 20, 2014

Same-Sex Classes Appear to Diminish Women’s Risk Aversion

Female economics and business students were 19% more likely to make risky choices in a financial experiment if they had spent the last eight weeks in single-sex, versus coed, classes, says a team led by Alison Booth of Australia National University. The experiment involved choosing between a safe option for receiving money and entering a lottery with an uncertain but potentially greater payout. The results suggest that a part of women’s observed greater risk aversion (in comparison with men’s) might reflect social learning rather than inherent gender traits, the researchers say.

What Executives Really Need to Know About the “Emerging Markets Crisis”

As currencies and stock markets have tumbled in emerging markets, the business media has been dominated by cries of an “Emerging-Markets Crisis.” Corporate executives would be well served to turn off the television. Multinational companies do have their work cut out for them, and should take a second look at their 2014 plans — but this requires separating the signal from the noise to focus on their most important management challenges.

The media uses “emerging-markets crisis” as shorthand, but recent market turmoil was actually about relatively few countries.

For those of us who work on the ground in emerging markets, or who follow them closely, few of the headlines were all that startling. Yes, there are real reasons for MNCs to be concerned about political instability in Turkey and Ukraine, and economic policies in Argentina and China – all of which have occupied front pages recently. But these risks were known months ago.

Last fall my research team at Frontier Strategy Group designated Ukraine, Turkey, and Argentina as most vulnerable to a liquidity crisis because of their high levels of short-term external debt. For such countries, even moderate changes in investor sentiment cause major currency movements. Unfortunately, the media tends to gloss over key differences in their market fundamentals, especially the ones that matter to companies.

If you’re playing catch-up, here’s what you really need to know about these hotspots of market volatility:

In Latin America, Argentina’s devaluation was the spark that lit recent currency turmoil. (Again, this was a known risk; we forecasted a post-election devaluation last May.) We believe the peso has further to fall but timing is difficult to predict, so if this region is vital to your business, contingency planning is the order of the day.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East the political crisis surrounding Prime Minister Erdogan made Turkey a target for currency traders. We expect political instability and currency depreciation to continue despite the central bank’s aggressive interest rate hike, contributing to softened demand in the first half of 2014. That said, 2014 disruptions are unlikely to diminish medium-term growth, presenting an opportunity to “buy low.”

Ukraine’s mass protests have topped headlines for months, since President Yanukovich discarded an association agreement with the EU in favor of direct Russian aid. As far back as August, worrying economic fundamentals led our analysts to warn of a 10-30% devaluation of the hryvnia. MNCs in Ukraine should expect to endure significant business disruption, including liquidity crunches and delayed public and private investment.

In China, slower growth is not a crisis, even though many financial analysts cite it as a reason for recent market churn. It is in fact evidence of a transition from an overextended investment-led economic model to a sustainable consumer-led model. The excessive bad debt in China’s shadow banking system, however, could lead to a real crisis.

In each of these cases, the most serious risk is not of contagion collapsing currencies across emerging markets, but rather repeated bouts of volatility driven by fund-manager portfolio reallocation and herd mentality. This can have deeply disruptive effects. Some markets are likely to experience extreme volatility on an ongoing basis (Argentina, Iran, Syria, and Belarus top our volatility index forecast). Factors we’re watching that could increase the likelihood of a currency crunch include short-term external debt, current-account balances, and portfolio capital outflows.

Business leaders at MNCs should take five critical actions now to mitigate the impact of likely currency volatility in 2014:

Create contingency plans for repatriating profits in hard currency in the event of local-currency devaluation or if capital controls are imposed.

Prepare to support local partners financially in the event of a liquidity crunch, a strategy that could earn enduring loyalty.

Consider localizing production and sourcing to maintain price competitiveness.

Review your geographic portfolio based on market fundamentals, and consider investing more aggressively in frontier markets that are relatively resilient to currency shocks such as Nigeria, Peru, and Kazakhstan.

Define disruptive events that would call into question the underlying assumptions of your 2014 plan, and should therefore trigger a mid-year course correction in targets or resource allocation.

Above all, don’t let Wall Street or the headlines distract you from execution – or rewrite your business plans. Keep your eye on what matters to your company’s success, and the timeframe in which you are committed to deliver results. You don’t control the markets, but you can control your business.

February 19, 2014

How to Explore Cause and Effect Like a Data Scientist

The ability to think analytically is important for any manager today. The first steps, as I’ve explained before, involve collecting data, making some simple plots, drawing basic conclusions, and planning next steps. But data do not give up their secrets easily. While we can use data to understand correlation, the more fundamental understanding of cause and effect requires more. And confusing the two can lead to disastrous results.

Every manager must make the distinction between “correlation” and “cause and effect” regularly, as the topic comes up in many guises. New production, marketing, planning, and investment issues, requiring a careful look, come all the time. Big data and advanced analytics produce unexpected correlations, and separating the real opportunity from the spurious tease is essential. Finally, much of management involves taking actions on things you can control to affect desired results.

I’ll use my own personal diet data to explore the two.

As background, I’ve been blessed with great health. I like to exercise and get plenty. Still, over the years my weight has crept up. The problem is that I also like to eat! I’ve given passing thought to dieting, but other than a few points that have been hammered into all of us (e.g., “Too much red meat is bad for you.”), I don’t understand nutrition. Until last September, I always found a convenient excuse not to do it.

Starting September 22, I followed the prescriptions of my last blog. I found a program on the Internet where I could log my food intake. This was a bit more difficult than I expected, but I kept at it. And after three months, I drew some plots. To be clear, I publish these plots because they are so utterly typical of the successful analyses I’ve participated in throughout my career.

In the first plot below, I plotted my weight (blue dots) and my daily calorie intake (blue line). The plot also features a “recommended calorie range” (green lines).

Now let’s dig in. It is easy to see that I ate way too much in weeks two through four, and my weight went up. This makes sense — there is a causal link between caloric intake and weight gain. This correlation has a real-world explanation.

Unfortunately, the obvious recommendation — “Eat less” — is wholly unsatisfying! If I could do that, I wouldn’t be overweight. We need to dig a little deeper.

One possible explanation is that I was traveling most of those weeks. I’ve marked it and subsequent travel on the plot. The plot confirms my suspicions: My already dubious eating habits are even worse when I travel.

Note that even though the correlation between travel and weight is tantalizing, the plot does not, in and of itself, nail cause and effect. I feel certain that I don’t travel because I eat too much. But I don’t know yet why I eat too much when I travel. There are deeper factors awaiting discovery. Is the problem some combination of eating at unfamiliar restaurants, too many “drinks and dinner,” too much fast food in airports, or something else? I simply do not know yet. Travel qualifies as a “proximate” cause of my poor weight control, but not as a directly addressable “root” cause.

This discussion underscores a critical point: While correlation doesn’t imply causation, it does provide give me a great starting point from which we can dig deeper into the data, consider other evidence, and so forth.

My weight gain in the two weeks through November 9 was initially puzzling, as I kept my calorie intake in the acceptable range. Then I plotted of my weekly “fitness minutes.” My exercise was way down during that period. Again, makes good sense — exercise consumes calories, and less exercise means more weight. I can’t fall down on my exercise regimen!

But let’s be careful. While lack of exercise appears to qualify as a root cause, it may not be that simple. It could be that more exercise leads me to eat more, nullifying calories burned. For example, I often take a long bike ride on summer Sundays. If memory serves, I’m ravenous those evenings. But at this point, I don’t have the data to investigate. So exercise only qualifies as a “root cause, all other things being equal.”

The final plot in this post is my fat consumption each day. Even during the later weeks, when my overall calorie consumption was a bit lower and my weight held steady, I ate way too much fat. I consulted a nutritionist, and she advised that a gram of fat has nine calories, and a gram of carbohydrates only four! Note that, even though I’ve not established a correlation in the data, my suspicion about fat intake is motivated by a compelling explanation of the underlying reality.

My next step was simply to go through my nine “highest fat days,” identify three big offenders and cut way back on them.

Here’s why these analyses are so relevant. First, you simply must have the data. My intuition tells me that exercise is good for me, but my intuition about diet, until last September, was quite often wrong! So too in business. In my consulting, people tell me all the time, “We know…” whatever it is. Sometimes they are right. But often they are just plain wrong.

Second, you can’t be afraid to ask hard questions of both the data and others. I’m no psychologist, but I think some of the “we know…” machismo is rooted in fear of being wrong. Similarly, I felt silly talking to the nutritionist, but she helped me gain a better picture of why fat matters.

Third, you have to be on the lookout for bad data. My calorie intake looks way too low on two days, so I plotted them using a red x. It is almost always the case that some data can’t be trusted. Dealing with bad data is increasingly important when the distinctions are fine or stakes are high, but when there are relatively few suspect points you can often complete an analysis or two with little worry.

Fourth, a few, well-chosen plots provide great clues to root causes. In my case, potential contributors to weight management around travel, exercise, and fat intake have all clarified themselves. At the same time, we can’t yet confirm that any are root causes. That requires data and a deep understanding of “what’s going on” that reinforce one another. This is the norm in all of business.

Fifth, it is all too easy to confuse correlation and root cause. I heard great example recently. My son and his wife had attended a workshop at which a presenter noted that “there’s a lot more sex in households where husbands share the child rearing and housework.” An interesting correlation, but devoid of cause and effect. Do husbands doing more housework lead to sex, or does sex lead to husbands doing more housework? Or are there deeper factors at work? Indeed, the correlation may not even be correct. Rather than assume causation, treat correlation as a clue to be combined with other evidence to reach a conclusion. Correlation isn’t causation. But it is a terrific starting point!

As I draft this post, some six weeks after making these plots, I’ve lost four pounds. Impressed? Don’t be! People lose that amount of weight all the time. As in all business, the real questions are “Will it work long-term?” and “Will I have the discipline to follow through?”

Finally, of course, these plots are only the beginning. Nutrition, like business, is complex. Those who understand it will surely ask, “Are you eating enough fruit?” “How about saturated fat?” or “Where does hydration fit in?” In every useful analysis, the first few plots inevitably lead to others.

As with my last post, I hope readers get excited that they can and must use data to explore cause and effect. After all, analytics is too much fun to leave for the data scientists!

The “Older” Entrepreneur’s Secret Weapon

In the early days of founding my current company, The Grommet, I met with a prominent venture capitalist. His firm had a summer incubator program for student entrepreneurs. As we chatted, two of those young in-resident founders walked by. The investor shook his head admiringly and said to me, “Those kids are here all hours of the day.” Then he paused thoughtfully and questioned, “Can you do that?”

I guess he assumed that, as a 47-year-old woman with three sons at home, I would turn into a pumpkin at 5pm every day — with the call of dinner preparation demanding my presence. I ignored the blatant bias and answered, “What do you mean could I work like that? I already do.”

Five years later I am at the helm of a company that grew its revenues 450% in 2013, and counts one in 200 Americans as a supporter. The young pair of founders I saw, who eventually raised over $50M in venture capital funding, are no longer at their venture.

There are two points to this story. I will leave one of those points — investor bias — to another time. But the second point — about the advantages of being a middle-aged company founder — is often overshadowed by a media archetype of start-up founders as hoodie-clad 20-something’s. In reality, studies show that one of the identifiable success factors in creating a high-growth start-up is having founders who graduated from college and were older at the time they started their companies, because they therefore tended to have more experience and more contacts to build successful large firms. In fact, the average age for founding a successful company is 40.

It’s not a revolutionary insight to expect that experience and networks matter.

However, in building The Grommet, I have experienced and observed that there is a hidden advantage to this life-stage: more mature adults tend to have more significant social and family supports to give them resilience to survive the brutal psychological assaults of creating a company. In other words, there are plenty of “credits” to balance the “debits” of kids, mortgages, and looming college tuitions.

For me, family provides a separate identity outside my company, a consistent outlet for rest and relaxation, and a safe haven to escape the relentless pressures of building a business. These social supports go far to replenish the necessary reserves of energy, courage, and tenacity that are essential to successfully leading a start-up.

But what about the kids anyway? With a family, people assume that children will pull the entrepreneur dangerously away from minding the store. Indeed, in the early years of The Grommet, the business itself did feel a lot like a newborn baby. And if I had had a real, live newborn, it would have been a desperate and impossible tug of war. The business required constant attention and it completely dominated my every waking and sleeping moment. Seeing me frequently preoccupied, one of my three sons learned to say, “Mom, you are off in email land again.” He noted the figurative steam coming off my brow and realized I was composing a response to a request or challenge (usually related to people or capital!) in my head.

But my sons were also teenagers, not newborns or toddlers. I had taught them plenty of critical life skills, like cooking. They did not need (or want) my constant presence and when we do have dinner together (always, but admittedly very late at night) they, or my husband, are as likely to have cooked the meal as me. We talked about the business constantly those first few years and they helped me think through issues, serving as an interested sounding board.

My sons saw firsthand that the first five years of the business were a relentless battle for survival. In fact, there were three distinct moments when the business was on the brink of extinction. At the most harrowing of those times, I prepared the boys for the worst and my youngest son forcefully replied, “You can’t quit now Mom. Look at all you have gotten through. What do you tell us when the going gets tough? I am telling you that now!” That exhortation was deeply, and uniquely, galvanizing for me. A mere financial investor could not have had that profound effect on my psyche and I pulled it out — yet again.

One advantage of having older children is they can directly appreciate the business milestones that my company experiences. Over time, I realized that my sons’ own identities came to include having a mother who is an entrepreneur. I was so tickled when my middle son made it a priority to show his visiting girlfriend our company’s offices. And when Fortune named me one of the 10 most powerful women entrepreneurs, my sons kept me humble, taking great amusement in awarding me membership in their list of “10 most annoying mother entrepreneurs”.

The bottom line is that my sons contribute energy and drive for me, rather than the reverse. They are the secret weapon in my psychological armor.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Executives’ Biggest Productivity Challenges, Solved

A Successful International Assignment Depends on These Factors

How an Olympic Gold Medalist Learned to Perform Under Pressure

Tackle Conflicts with Conversation

What Drones and Crop Dusters Can Teach About Minimum Viable Product

Teams that build continuous customer discovery into their DNA will become smarter than their investors, and build more successful companies.

Awhile back I wrote about Ashwin, one of my ex-students who wanted to raise a seed round to build Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (drones) with a hyper-spectral camera and fly it over farm fields collecting hyper-spectral images. These images, when processed with his company’s proprietary algorithms, would be able to tell farmers how healthy their plants were, whether there were diseases or bugs, whether there was enough fertilizer, and enough water.

(When computers, GPS and measurement meet farming, the category is called “precision agriculture.” I see at least one or two startup teams a year in this space.)

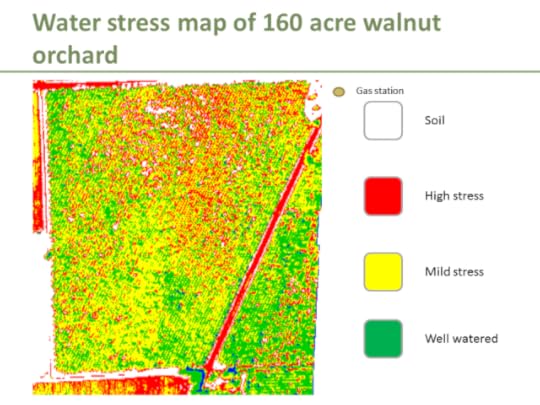

Precision agriculture in practice. Image via Steve Blank.

At the time I pointed out to Ashwin that his minimum viable product was actionable data to farmers and not the drone. I suggested that to validate the minimum viable product it would be much cheaper to rent a camera and plane or helicopter, and fly over the farmers field, hand process the data and see if that’s the information farmers would pay for. And that they could do that in a day or two, for a tenth of the money they were looking for.

(Take a quick read of the original post here.)

Fast forward a few months and Ashwin and I had coffee to go over what his company Ceres Imaging had learned. I wondered if he was still in the drone business, and if not, what had become the current minimum viable product.

It was one of those great meetings where all I could do was smile: Ashwin and the Ceres team had learned something that was impossible to know from inside their building.

Crop Dusters

Even though the Ceres Imaging founders initially wanted to build drones, talking to potential customers convinced them that as I predicted, the farmers couldn’t care less how the company acquired the data. But the farmers told them something that they (nor I) had never even considered – crop dusters (or “aerial applicators”) fly over farm fields all the time (to spray pesticides.)

They found that there are ~2,400 of these aerial applicator businesses in the U.S. with ~5,000 planes. Ashwin said their big “aha moment” was when they realized that they could use these crop dusting planes to mount their hyperspectral cameras on. This is a big idea. They didn’t need drones at all.

Local crop dusters meant they could hire existing planes and simply attach their hyperspectral camera to any crop dusting plane. This meant that Ceres didn’t need to build an aerial infrastructure – it already existed. All of sudden what was an additional engineering and development effort now became a small, variable cost. As a bonus it meant the 1,400 aerial applicator companies could be a potential distribution channel partner.

The Ceres Imaging minimum viable product was now an imaging system on a crop-dusting plane generating data for high value Tree Crops. Their proprietary value proposition wasn’t the plane or camera, but the specialized algorithms to accurately monitor water and fertilizer. Brilliant.

I asked Ashwin how they figured all this out. His reply, “You taught us that there were no facts inside our building. So we’ve learned to live with our customers. We’re now piloting our application with Tree Farmers in California and working with crop specialists at U.C. Davis. We think we have a real business.”

It was a fun coffee.

Lessons Learned

Build continuous customer discovery into your company DNA

An MVP eliminates parts of your business model that create complexity

Focus on what provides immediate value for Earlyvangelists

Add complexity (and additional value) later

Understanding the Copyright Wars: Aereo, Google, and GoldieBlox

To infinity… and beyond!, cries Pixar’s Buzz Lightyear. Disney, which bought Pixar in 2006, knows what infinity looks like: copyright protection. Due in large part to Disney’s lobbying efforts, copyright protection now extends throughout the life of the author plus an additional 70 years. For corporate works, the copyright lasts 120 years from creation or 95 years after publication.

Because when copyright protection is granted today, it is granted essentially for an entire century, the scope of copyright protection is among the most contested areas of law. The fight most often comes down to what constitutes unlawful copying and what is fair use.

The controversy around recent cases involving Google, GoldieBlox, and Aereo show we may need a refresher on this topic, and a reminder that fair use does include commercial use. A common misconception about fair use is that it applies only to not-for-profit uses, such as academic or political commentary. This is not the case, as these recent legal battles show.

Recently, after a decade-long legal battle, Google succeeded in its defense against a class action suit by publishers and the Authors Guild over the Google Books project of scanning more than 20 million books. Courts ultimately decided that Google Books constitutes fair use: millions of books buried in library archives are now discoverable through Google searches but are only revealed in snippets. The entirety of the copyright work remains out of the public domain. In other words, Google Books provides an invaluable research tool for students, teachers, librarians, and anyone doing any kind of research that benefits from searching, identifying, and locating relevant books, while not adversely impacting the rights of copyright holders. Google Books represents a major victory for Internet search engines and consumers. Google of course makes billions in advertising revenues, but the public benefit of the Google Books project offsets publishers and authors decrying copyright infringement.

The same issues are at stake in the current litigation between the blossoming Palo Alto toy company GoldieBlox and the band the Beastie Boys. GoldieBlox’s commercial went viral with a parody of the Beastie Boy’s song “Girls.” The message of the ad is clear: stop selling silly pink toys to little girls and instead encourage them with toys that might lead them to study STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and math). The Beastie Boys sued the toy company, claiming that since the video was aimed at selling a product, it cannot be deemed fair use. Not true, especially these days, where successful advertising is tightly intertwined with social commentary, some commercials can be deemed fair use. Fair use protects parody and social critique, but those can be made in a for-profit context. The GoldieBlox commercial had a dual purpose: to sell toys and to criticize the misogynist stereotypes in the original Girls song. These two goals are rolled into one in the GoldieBlox toys themselves, which are carving out a new market for toys that empower girls.

Fair use is a judicial balancing act: it helps your case if you have a strong social message, a transformative and non-competing use, and minimal harm to the original creator. The courts will also consider the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work. Here, unlike with Google Books which only revealed snippets of the books it lawfully scanned, the Girls song is presented in full, but it is entirely parodied and transforms the work into something different. While fair use is applied case-by-case in a highly context specific manner, in this case, overall the factors stack in favor of GoldieBlox.

But both of these cases are actually fairly straightforward when contrasted with a case currently on the Supreme Court’s docket, ABC, Inc., v. Aereo, Inc. The Court will have to decide whether the online streaming of broadcasts is a copyright violation. Big broadcasters such as ABC are claiming that small tech startups like Aero and TV Catchup, which allow audiences to watch their favorite TV shows on their laptops, tablets, and smartphones, infringe on their copyrighted programs. In this case, like in analogous cases in the past such as the Sony Betamax VCR and the Cablevision DVR, the court should allow new technology to stand as long as the device is capable of substantial non-infringing uses. In the Betamax case, the court ruled that the selling of video tape recorders allowing the general public to record broadcasts was not a copyright violation. The court reasoned that the average consumers use the VCR to record a program they couldn’t watch while it was televised. The court emphasized that such private time-shifting in fact enlarges the television viewing audience and therefore doesn’t impair the commercial value of the broadcaster’s copyright. Next came the DVR, which provided a service, rather than a recording box, for time-shifting. The court viewed the two as functionally equivalent and held that this technology similarly does not infringe on the copyright of the broadcaster. The principle that has been established in this line of cases is that technology providers are not infringing copyright when they aid individual consumer to control the ways in which they privately watch programming. Like with previous technologies, Aero is providing viewers a new way to access content, this time through the Internet. Copyright law was not intended to prevent the introduction of such new technology.

Notice that even though the technology subject to the current copyright debate is new, the debate is age-old. As consumers we desire more options, new ways to get content, and new technologies that provide flexibility and choice. This means that traditional content providers lose some control. The large networks fought the VCR and the DVR and lost. Ultimately, these new technologies gave rise to the profitable (for a long time anyway) practice of selling movies direct to the consumer despite movie studios’ fears that it would bring down their industry. Incumbent industries have always argued that new forms of access will bring the industry to destruction, while in practice the technological advances open up new business models and new forms of competition and profit.

But don’t just take my word for it. New empirical studies demonstrate mounting evidence that contemporary copyright law actually hinders the arts. One new study shows that Amazon sells far more books published in the 1880s than in the 1980s, because the strong copyright holds on recent works prevent their distribution. Copyright expiration revives lost art. Another study finds that for composers and musicians, it is only the top income brackets that depend heavily on revenue related to copyright protection, while for the vast majority of other musicians copyright does not provide a measurable direct financial reward for their art. A third study suggests that less copyright protection in music actually results in the creation of more, not less, new music.

The current copyright wars are best understood against the backdrop of the draconian length of copyright protection and the public discontent with unreasonable enforcement. When human creativity is artificially monopolized beyond reason, the very purpose of intellectual property, to promote progress in arts and science, is subverted.

It Just Got Easier for Companies to Invest in Nature

Nature is valuable. But figuring out how valuable has been challenging. By some measures, the services that nature provides business and society — clean water, food and metals, natural defense from storms and floods, and much more — are worth many trillions of dollars. But that number is not helpful to companies trying to assess how dependent they are on natural resources, or how to value them as business inputs.

In recent years, many large companies have realized that they need to get a handle on these issues, and that doing it well creates business resilience. But figuring out what steps to take has been challenging. Into that void steps a new, very helpful tool, the Natural Capital Business Hub. The Hub is a project run by the Corporate EcoForum, The Nature Conservancy, and The Natural Capital Coalition (and built by Tata Consultancy Services). It builds off a partnership launched at the Rio+20 summit in 2012 with companies such as Alcoa, Coca-Cola, Disney, Dow, GM, Kimberly-Clark, Nike, Unilever, and Xerox. At the time, they produced a report with case studies showing how companies have managed natural capital issues. The Hub expands that effort, making much more information available and searchable.

The Hub basically does four things:

Provides case studies of corporate action for benchmarking and learning, which you can search by industry, region, ecosystem, or value-creation focus (cost reduction, brand building, etc.).

Offers perspective on how to make the business case internally by laying out how valuing natural capital helps business.

Gives us a framework for implementation and a thorough description of (or links to) the best tools for valuing and managing natural capital.

Opens up collaboration opportunities by listing programs that need more partners and builds a network of professionals (with 2Degrees Network) who are working on these issues.

The case studies are ostensibly the core of the site. Project managers, facility heads, executives who make capital decisions, sustainability managers, and many others can learn from the work that leading companies have done already. Managing natural capital is a young field, but Dow, for example, is now three years into its six-year partnership with The Nature Conservancy to “recognize, value, and incorporate the value of nature into business decisions, strategies and goals.” (The company just released the latest update on the partnership.) The Hub is a place to start your research and learn from Dow and many others.

On the site, you can find stories of completed projects or prospective collaborations that need more partners to get off the ground. In the first category, you’ll find stories like the one about Grupo Bimbo, the Mexican food company that owns Sara Lee, Hostess, and Pepperidge Farms. Bimbo needed to manage stormwater around a site in Pennsylvania. Using natural or “green” infrastructure such as rain gardens and forest buffers — versus “gray”, manmade systems like retention ponds and pipes — the company reduced ongoing operating costs and avoided the complications of burying pipes in sensitive ecosystems.

On a somewhat larger scale, consider Darden restaurants (owner of Olive Garden, Red Lobster, and many more) and its efforts to save fisheries. As companies like Unilever and McDonald’s have long recognized, ensuring healthy fish stocks isn’t a philanthropic nice-to-have, but core to business survival: no fish, no fish sticks, lobster plates, or Filet-O-Fish sandwiches. Darden is working with the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation and others to target valuable fisheries and manage them closely.

What’s interesting about the Darden case study, and the Hub in general, is that this project is just getting started — essentially, it’s an open call for collaboration. The Hub is innovative and helpful because of the partnership tools. Natural capital issues are not easy and cross many lines – every company, city, and home in a region, for example, depends on water and flood protection. No organization or region can act alone, and it shouldn’t. By listing the major collaborations that are actively searching for new partners, the Hub has done a great service.

A Messy Environment Makes It Harder for You to Focus on a Task

In an experiment, people who sat by a messy desk that was scattered with papers felt more frustrated and weary and took nearly 10% longer to answer questions in a color-and-word-matching task, in comparison with those who were seated by a neatly arranged desk, say doctoral candidate Boyoun (Grace) Chae of the University of British Columbia and Rui (Juliet) Zhu of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in China. A disorganized environment appears to threaten people’s sense of personal control, and the threat depletes their ability to regulate themselves, the researchers say.

Seven Problems Your Inbox Can Solve

When you’re staring at an inbox piled high with unread emails, it’s easy for email to feel like yet another problem for you to solve. But by using your email’s rules and filters, you can not only prevent those messages from piling it up, but address challenges you face that go beyond your inbox.

A mail rule scans your incoming email for specific messages (for example, from a certain person, or containing a specific set of keywords) and handles those messages in a way you’ve predefined: by filing them in a particular folder so you can look at them when they are relevant.

Here are seven of the biggest challenges I use email rules and filters to address:

I miss important messages in a sea of newsletters. Even if you’ve got great spam filters, your inbox can easily fill up with not-quite-junk like industry newsletters and deal alerts. By streaming all of these into a separate folder, you can create one place to quickly scan through them for something important, without letting them clog up your inbox. To do so, create a mail filter that searches for common bulk mail phrases such as “to unsubscribe click” and “please unsubscribe.” If you want a separate folder just for your deal alerts, set up a filter that looks for emails with both unsubscribe links and phrases like “sale” and “deal.”

I can’t stop checking my inbox. Committing to a specific email schedule and turning off “push” on your mobile device can help break the habit of obsessive email check-ins. But sometimes the compulsion is driven by a specific email you’re anticipating (like a job offer) and can’t wait to see. Set up your mobile phone as a forwarding address (you can find the address formula for major US mobile providers here), and when you find yourself obsessively checking for a specific incoming email, create a mail rule that will forward that email to you as a text message as soon as it arrives. That way you can trust in your phone to alert you when it arrives, and stop checking your inbox.

I’m scared of missing a message from my boss. You can also use mail rules if you’re nervous about missing an email from a VIP like your boss by creating a “boss filter” as a kind of safeguard for all your other filters. In Outlook, create a mail rule that flags any email from your boss, and specifies that no other rules apply to messages that meet the criteria for this rule. Place the rule at the very top of your rules list; because Outlook applies rules in order, your boss’ emails will never get placed somewhere else. In Gmail, create a rule that marks any message from your boss as “important,” and flip the “filtered mail” setting under Settings/Inbox so that important messages override your other filters. If the unmissable correspondent is someone you hear from only rarely (for the example, the CEO of a large company in which you’re a mid-level manager) you might even give your boss filter the text message treatment, so that an email from the CEO goes straight to your mobile phone.

I am frazzled from juggling too many projects. If your job involves multiple areas of responsibility or managing many concurrent projects, your inbox probably reflects that mix. But there’s a cognitive cost to switching from one task or focus to the next, and if the job of processing your inbox involves jumping around between your many projects, you’re likely wasting a lot of mental energy. Consider creating a separate folder and rule for each major project, account, or area of responsibility you handle, so that each one gets its own alternate inbox. That way you can read and reply to all related emails at one time, before shifting gears to focus on your next project.

We need more business. If you’ve ever found a weeks-old unanswered business inquiry or quote request buried in your email backlog, you know the pain of missing out on business opportunities due to email chaos. Whether you are watching out for an RFP, a call for papers, or a job posting, there is likely some type of opportunity that you’d hate to lose in a crush of incoming email – or conversely, which you only want to review at specific times, rather than get distracted from your work whenever an opportunity arrives. Set up a rule that looks for the relevant keywords in a subject line (e.g. “Call for Papers”) and shunts all such messages to a specific folder.

I spend too much time on scheduling. The time you spend in meetings can easily be dwarfed by the amount of time handling all the messages that fly back and forth in the course of setting those meetings up: the multiple, ever-changing meeting requests, accepts, and declines. Those meeting-related messages can consume a huge chunk of your email time budget, but they don’t have to. Direct all calendar requests and RSVPs (anything with an .ics file attached) to a special folder, and review your calendar (rather than your calendar-related messages) once a day to spot any tentative meetings or appointments you need to accept. There’s no need to look at actual calendar-related email messages unless you need to see why someone hasn’t RSVPed to a meeting invitation you’ve extended, or until it’s time to prep for a meeting (when you’ll want to look at the invitation to see if there is an agenda or materials to review).

My workday is full of personal interruptions. If you use the same email address for both business and personal correspondence, it’s easy to let your friends and family disrupt your concentration during the workday with personal gossip, notifications of upcoming school concerts, or reminders to pick up the dry cleaning on the way home. Set up one or more filters to catch email from your most frequent personal correspondents, whether that’s your spouse, your kids, your parents or your BFF, and direct them to a “personal” folder. Check your personal folder in the evening or during your commute; if you need to check in on the home front more often, you can take a peek during your lunch hour, too. The key is to keep your personal email sequestered so it doesn’t break your concentration at the office.

You can find more types of filters as well as more detailed instructions about how to build them in my new book, Work Smarter, Rule Your Email.

I use filters like these to channel mail into what I think of as “alternate inboxes”: mail folders that keep certain kinds of messages out of my inbox, but which I commit to checking at least once a day, depending on what’s in them. Limiting my inbox to the most urgent and important messages ensures they are the first thing I see when I check my email during the quick email check-ins I scatter throughout my day, while creating specific “alternate inbox” folders means I still can be sure I see those messages when I sit down for a longer window of dedicated email time. With a system like this, I’m able to get to the messages I need to address quickly, and to use email to make me more productive, rather than less.

February 18, 2014

Three Mistakes to Avoid When Networking

We all know networking has the potential to dramatically enhance our careers; making new connections can introduce us to valuable new information, job opportunities, and more. But despite that fact, many of us are doing it wrong — and I don’t just mean the banal error of trading business cards at a corporate function and not following up properly. Many executives, even when they desperately want to cultivate a new contact, aren’t sure how to get noticed and make the right impression.

I’ve certainly been there. Years ago, I was a speaker at a tech conference — as was a bestselling author. By chance, we met in the speakers lounge and, massively unprepared, I fell back on platitudes. It’s great to meet you! I love your work! I handed him my card. If you’re ever in Boston, it’d be a pleasure to meet up! He hasn’t called, and frankly, I’m not surprised.

We’re all busy, but it’s hard to imagine the volume of requests that well-known leaders receive. Reputation.com founder and fellow HBR blogger Michael Fertik told me he receives anywhere from 500-1000 emails per day, and describes it as “a huge tax on my life.” Wharton professor Adam Grant, who was profiled by the New York Times for his mensch-like habit of doing almost anyone a “five minute favor” was rewarded for his generosity by being inundated with 3500 emails from strangers hitting him up. “I underestimated how many people read the New York Times,” he jokes.

Grant does get back to the people who write him — he even had to hire an assistant to help — but most people at the top don’t have the time management skills (or the desire) to pull that off. If you want to network successfully with high-level professionals, you have to inspire them to want to connect with you. Through hard-won experience, I’ve learned some of the key mistakes aspiring networkers make in their quest to build relationships, and how to avoid them.

Misunderstanding the pecking order. The “rules” for networking with peers are pretty straightforward: follow up promptly, connect with them on LinkedIn, offer to buy them coffee or lunch. I’ve had great success with this when reaching out to people I had an equal connection to: we’re both bloggers for the same publication, or serve on a charity committee together, for example. People want to congregate with their peers to trade ideas and experiences; your similarity alone is enough reason for them to want to meet you.

But the harsh truth is those rules don’t work for people who are above you in status. The bestselling author at the tech conference had no idea who I was, and no reason to. My book hadn’t yet been released, and his had sold hundreds of thousands of copies; he was keynoting the entire conference, and I was running a much smaller concurrent session. We make mistakes when we fail to grasp the power dynamics of a situation. It would be nice if Richard Branson or Bill Gates wanted to hang out with me “just because,” but that’s unlikely. If I’m going to connect with someone far better known than I am, I need to give them a very good reason.

Asking to receive before you give. You may have plenty of time to have coffee with strangers or offer them advice. Someone who receives 1000 emails a day does not. Asking for their time, in and of itself, is an imposition unless you can offer them some benefit upfront. Canadian social media consultant Debbie Horovitch managed to build relationships with business celebrities like Guy Kawasaki and Mike Michalowicz by inviting them to be interviewed for her series of Google+ Hangouts focused on how to become a business author. Instead of asking them for “an hour of their time” to get advice on writing a book, she exposed them to a broader audience and created content that’s permanently available online.

Failing to specifically state your value proposition. Top professionals don’t have time to weed through all the requests they get to figure out which are dross and which are gold. You have to be very explicit, very quickly, about how you can help. My incredibly weak “Let’s meet up in Boston!” isn’t going to cut it. Instead, you need to show you’re familiar with the person’s work and have thought carefully about how you can help them, not the other way around. Tim Ferriss of The 4-Hour Workweek fame blogs about how his former intern Charlie Hoehn won him over with a detailed pitch, including Charlie’s self-created job description touting his ability to help create a promotional video for Ferriss and an online “micro-network” for fans of his books.

Networking is possibly the most valuable professional activity we can undertake. But too often, we’re inadvertently sabotaging our own best efforts by misreading power dynamics, failing to give first, and not making our value proposition clear. Fixing those crucial flaws can help us connect with the people we want and need to meet to develop our careers.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers