Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1470

February 12, 2014

Can’t Find a Steve Jobs? Hire an Innovation Organizer Instead

Improving innovation is one of the key competencies that companies often look for when replacing a CEO. Yet committees responsible for recommending candidates often grapple with finding the right person for the job when an innovation emperor like Steve Jobs isn’t available.

A study of more than two dozen consumer packaged goods companies that I led while working as a senior executive at Nielsen reveals exactly what they should be looking for instead: an innovation organizer.

An innovation organizer creates an environment ripe for innovation. I’m not talking here about leaders with vague or feel-good principles like being open to new ideas; rather, those guided by a set of specific requirements, actions, and structures proven to drive innovation, which include the following:

Personally stay out of creating new products and services. While that might seem counterintuitive, the findings of the Nielsen study indicates that when CEOs and other high level executives get involved in creating new products and services, revenue from the new products drops by 80%. While savvy about understanding and leading the organization, high level executives are often so far removed from the distinctive customer needs in their various lines that they are likely to make bad decisions about new products. Instead, an innovation organizer makes sure that those closest to the innovation are indeed making the decisions and are not being second-guessed.

Ensure that clear and explicit decision-making criteria are created, constantly improved, and rigidly followed. In fact, leaders that make sure their organizations do this average 130% more revenue from new products, according to the Nielsen research. Today even when decision-making criteria exist, they are invariably incomplete. Informal understandings between individuals too often determine what moves forward, leaving the rest in the dark. Innovation organizers set the expectation that decision-making criteria will be documented, complete, and almost always followed. They review the process periodically and act forcefully when protocol is being ignored. And they watch for and stop the common problem of their team members or other senior leaders pushing pet projects through product development. There should be no elite privilege when it comes to innovation. The senior leadership team needs to respect and adhere to the same standards as everyone else.

Never allow the organization to over-engineer the innovation process. As an example consider stage-gates, decision points at which time new products are reviewed before moving forward in the development process. A widely accepted best practice among even the most admired companies is to have five to seven. And that’s false when you look at the facts. Two to three are optimal. The study I led indicates that any more than that leads to revenue from new products dropping like a rock falling from 40% to 70%. Successful innovation requires a balance between analysis and structure versus the freedom to explore.

Find the truth. At 80% of CPG companies, when a new product succeeds everyone wants to be associated with it and few look closely at what didn’t go right. On the other hand, when it fails just about everyone takes a big step back while ignoring what may have gone well. Although an entirely logical response, given that success advances a career and failure kills it, innovation organizers strive to unveil the truth about what really happened — something Pixar, for one, does. They make sure that each product launch includes a formal and structured debrief to identify what went well and what could have been gone better. Ideally an outside facilitator leads the discussion and analysis, and the findings are captured permanently into a knowledge management system. When debriefs are formal and mandatory, revenue from new products increases by around 100%. When all three are followed, revenue from new products conservatively jumps by 200%.

Keep just about everyone away from breakthrough innovation. Companies with offsite breakthrough innovation teams tend to double their new product revenue compared to those that have them on-site. It’s easy to guess the reason for this outcome — conventional thinking of the existing organization inhibits the development of breakthrough ideas. As one CEO asked me, “Is 1,000 miles away far enough?” Maybe not. Fifteen or so years ago most of the U.S. and Japanese automakers moved their design studios to California — about 2,300 miles away from Detroit and 5,500 miles from Tokyo.

Step back and consider that Steve Jobs pretty much followed the principles I’ve just outlined. He stayed very close to the innovation. He was very clear about what he wanted. He learned a great deal from 40 or so years of being obsessively focused on personal computing — succeeding and failing spectacularly. And since he was the breakthrough innovation team, there was no corporate campus to escape from. As a result, the company’s financial returns were spectacular.

Of course, Steve Jobs was a rarity. The good news is it’s not necessary to have a larger-than-life personality to drive your innovation. Instead, an innovation organizer is a decisive leader who embeds the most important principles for innovation in the enterprise — principles that Jobs himself followed. In other words, an innovation organizer makes the entire company behave like Jobs. And when that happens, revenue from innovation skyrockets.

Stop “Fixing” Women and Start Fixing Managers

We are finally getting to a tipping point on the analysis of gender imbalances in companies. After decades of pointing the finger at women and what they do, don’t do, or do too much, a chorus of voices is finally being raised putting responsibility for balance where it belongs: with business leaders.

“The lack of women in an organisation is a management failure,” says a recent report published by King’s College London and sponsored by KPMG. I’ve seen the same in my work with large multinationals: There is only one key success criteria for gender balancing organisations, and that is leadership.

Not just the CEO’s commitment to change. But also top leadership’s recognition that they will need to educate, train and personally lead thousands of employees to have the management skills to be able to effectively work across genders. Just pointing out that 60% of university graduates and 70% of consumer-spenders are female isn’t enough to convince managers to behave differently. The CEO of KPMG UK, Simon Collins agrees. “Perhaps as CEOs we over-rely on the evidence of the business case to motivate our people to take action.”

This report’s recommendations for balance? The same as for most other strategic priorities. It has to be convincingly led by the CEO, be owned by all managers who, in turn, lead by example and who are able to communicate effectively why it is important to the business. This is hardly revolutionary. And yet relatively few companies have applied this sensible change management approach to the issue of gender.

In another report, McKinsey also pointed to the pivotal role leaders play in achieving gender balance. They found that the single most significant success factor for balance was the CEO’s leadership, and specifically how the CEO framed the issue. “The difference between the committed CEOs and others is subtle,” the report suggests. “The former make the goal clear and specific and tell everyone about it, while others fold ‘women’ into ‘diversity’ and ‘diversity’ into ‘talent,’” diffusing focus.

Sally Krawchek, one of Wall Street’s leading ladies and now head of 85Broads, a powerful women’s network, has added her voice to this perspective in a recent post. Among her ten tips for balance, one suggests, “Educate managers on the business differences between men and women in the workplace,” while another emphasizes, “And then spend even more educating your managers on the difference between men and women.” While this may sound obvious, it is extremely rare for any gender initiative to include men at all. Most companies’ efforts on ‘gender’ are still exclusively focused on women.

The shift in all this is that after a few decades of asking women to adapt to organizations, companies are starting to adapt their organizations to women. They are asking managers to learn new skills to manage a new more gender-balanced workforce and customer base.

The lesson beginning to emerge as companies’ progress on gender balance stalls is that we have relied on the wrong analysis of the problem. We have spent decades thinking that the lack of balance in business was caused by women doing the wrong thing or saying the wrong thing or even wearing the wrong thing. This led to an elaborate panoply of “fix-the-women” “empowerment” programs.

But now that women represent 60% of the educated talent on the planet, and half the incoming recruits of many companies, this argument is wearing thin. Half the population can’t be “wrong.”

But at last the collective wake-up call is hitting the mainstream. CEOs know it, yet still need to learn how to share their new-found understanding across global cultures and management levels. Doing so will take courage, conviction and clout.

So may the best CEOs balance their businesses… and may their companies’ enhanced business performance convince the rest.

How an Olympic Gold Medalist Learned to Perform Under Pressure

Alex Gregory is an Olympic rower, World Champion, and father of two. In 2012, he won gold in the coxless four at the London Olympics with teammates Tom James , Andrew Triggs Hodge , and Pete Reed . But success didn’t come easy — earlier in his career, he battled nerves and asthma, even blacking out in the water (twice). HBR talked to him about how he learned to thrive under pressure. This is an edited conversation.

You’ve been really open about how early in your career, you weren’t the best at performing under pressure. What would happen?

Although I liked the training, I never really loved the racing. Even at a young age I’d get nervous. In the early days, we were in a crew with two or three other people, and being in a boat with other people helped to calm my nerves. But to really pursue rowing, I had to learn to do it on my own in single scull. And that’s when I came into my difficult years, where things would go wrong. Basically it all boiled down to worrying too much about the result. It’s wanting something so much and worrying about it so much that you make it not happen. It became a vicious cycle: I’d fail, put even more pressure on myself, panic that I was going to fail, and fail again at the next event.

So how did you start to get your nerves under control?

About eight or nine years after I started rowing, I’d decided I was going to give up. I’d been very lucky to be invited as a spare man for the team going to the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, but I’d decided I wasn’t cut out for it and this would be my last event.

But then I got to Beijing. The Olympics is totally different. It’s everything. It’s what anyone aspires to be at. And sitting there on the sidelines, I just felt like there was something missing. I hadn’t achieved what I wanted to achieve.

And I realized that my answer had always been to practice technique. I had very good technique already — that was what had gotten me to where I was. But it was my physical strength that wasn’t good enough.

It was like a light switch went on. It was so simple, I couldn’t believe I hadn’t thought of it before.

I decided to give rowing one last chance. I spent three months just doing weights before I started training again with the guys. I could immediately see results — I was suddenly beating people who had always beaten me. It gave me so much confidence, and that confidence was all I needed.

It’s interesting to me that the lynchpin was focusing on improving a weakness. At HBR, we often tell people to focus on their strengths.

It’s so easy and much more fun to work on your strengths. You get immediate positive feedback — you looked great out there, that’s perfect, well done! But the thing you’re practicing, well, you were already good at it. You end up improving on that stuff naturally. So I think what you really need to work on is what you’re not good at. And I think that’s as true in business as it is in sport.

Rowing is unlike any other sport I can think of in the degree to which it balances the tension between competing as individuals and competing as a team. You compete against each other to win a seat in the boat, but then have to really come together as one for the race. How do you do that?

One of the most difficult things is racing against my mates. Andy [Triggs-Hodge] and Pete [Reed] are my friends, but we’re also competitors. I train every day, seven days a week, 350 days a year with the same 25 guys. Same lake, same day, same time. And for nine months of the year, we are competing against each other to make the seats. As soon as we’re brought into a crew by the coaches, we’re not competitors, but teammates.

Rowing is all about moving together. Not just a visual thing or an audible thing — it’s about feeling it. If someone is even slightly out of sync that will affect the boat speed. Molding it together comes from the coach watching from the outside, but also from all of us on the boat giving each other feedback.

For example, in 2011 we got in the boat and immediately it worked. We just clicked from the first stroke. It was magical — and we ended up winning the world championship. But when a new crew was selected for the Olympics, we took our first strokes together and it was almost the exact opposite. We were all moving in the right way pretty much, but the magic just wasn’t there. There was nothing the coach could see from the outside, and that kind of gets a little bit worrying when you’re supposed to be the top four guys in the country and you’re expected — and expecting — to win gold.

How did you figure out how to bring the team together then? Because you did end up winning the gold.

We really struggled for the first couple of months. We weren’t slow, but we knew that there was something missing. Australia had beaten us in the last [important race] before the Olympics. We knew we had to change something major, but we just couldn’t do it. And you can’t push back the Olympics if you’re not ready. You have to perform on that day. If you don’t, you fail.

But we’re fortunate in Great Britain to have a great resource in previous rowing champions who are available to talk with. Two of us, Tom [James] and I, went to talk with Matthew Pinsent. He gave us a lot of advice, but basically it boiled down to being totally honest in the boat.

When we got to our next training camp, we all chatted for two hours about what we wanted, what we were trying to achieve. We got down to how we wanted the stroke to look, the technical aspects of it. I could say very openly to Pete, “OK Pete, you need to do this part better.” And he could say to me, “Yes, and you’re not so good at this bit, Alex.” Earlier, I might have taken that personally and not really wanted to do it, because he’d told me to do it [laughs], you know what I mean?

Now the feeling in our boat was different. Earlier, we hadn’t been talking about the right things. We had to really take criticism and give criticism in a constructive way. Then for the next seven weeks, we knew exactly what we would be working on, on every stroke for hundreds of thousands of strokes.

So you come back from training camp for the Olympics, and this time, you’re not a “spare man.” You’re on the team. The games are in your home country. And the British team is competing for its fourth consecutive gold medal in this event. To me that sounds like an enormous amount of pressure. How did you deal with it?

The Olympics is unlike any other event — the crowd, the expectations, everything is bigger. There’s a buzz. I can’t remember the exact statistic, but the number of people who get a gold [medal] at their first Olympics is much smaller compared with people who have been to one before.

So for me, being in this particular crew was great, because the other three guys had won in Beijing. They’d already done it, so I had confidence in them. I can take the pressure off myself when I share that pressure with someone else.

We had also had quite a few discussions about what the pressures would be — of what it would be like to fly back to London having been in the private bubble of working in our own little boats. We were prepared because we’d talked about it beforehand.

Thinking back to earlier in your career, what do you wish you had known about performing under pressure?

That I have to have people around me, first of all. Back when I was racing solo, I’d be in the water on my own, at training camps on my own, in a room on my own. My coach was the only person I’d talk to for six or seven weeks at a time. It was incredibly isolating.

And second, that it always helps to talk about the problems. In those days, I would physically shake on the starting line at the start of a race because I was so scared I’d lose. It was a terrible time for me. But if I had spoken to my coach and been honest with him, then I’m sure he could have helped. It sounds a bit silly, but I was too scared of him thinking I was weak or that I couldn’t do it, that he would think I wasn’t good enough.

I think that people in all walks of life probably feel that — that they should do it all on their own. Now I think that doing it on your own doesn’t mean you can’t talk to people, get their advice, and be honest about the problems. You’re still the one going out there and doing it.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Tackle Conflicts with Conversation

What Would Make You More Satisfied and Productive at Work?

Doing Less, Leading More

Successfully Integrate Your Work, Home, Community, and Self

Customers Are Willing to Pay More When They’re Warm

Shoppers on a popular web portal were about 46% more likely to go to a “To Purchase” page when the daily temperature averaged 25 degrees Celsius (77 Fahrenheit) than when it averaged 20 degrees (68F), say Yonat Zwebner of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Leonard Lee of Columbia, and Jacob Goldenberg of the Interdisciplinary Center in Israel. The researchers also found that people in a warm room were willing to pay more than those in a cool room for 9 of 11 consumer items shown to them, and other participants were willing to pay 36% more for items when holding warm, versus cool, therapeutic pads. Exposure to physical warmth activates the concept of emotional warmth, eliciting positive reactions and increasing product valuation, the researchers say.

Is Europe’s Economy Really Sick?

You cannot pick up a business newspaper magazine these days without reading some article about Europe’s economic crisis; there seems to be an almost universal consensus that Europe is sick, that its institutional frameworks and governments are unfriendly to business, and that its prospects for getting better are dim.

For example, a survey answered by some 1,300 business executives worldwide that we conducted for INSEAD’s European Competitiveness Initiative shows that hardly anyone disagrees strongly with the proposition that innovation in Europe is hampered by a lack of culture of innovation and entrepreneurship, while about two thirds of those surveyed thought that Europe was actually unfriendly to innovation.

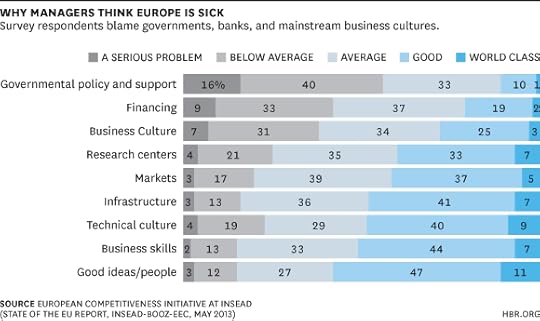

What exactly are the issues that people have with Europe’s innovativeness? Well, it’s not about the people. Half or more of those surveyed believed that European innovators were good, even world class, and that they had good business and technological skills.

The culprits were institutional. Most survey participants believed that government and financial institutions gave relatively little support to innovation. And while innovators may have had good business skills, the general culture of business in Europe did not encourage innovation.

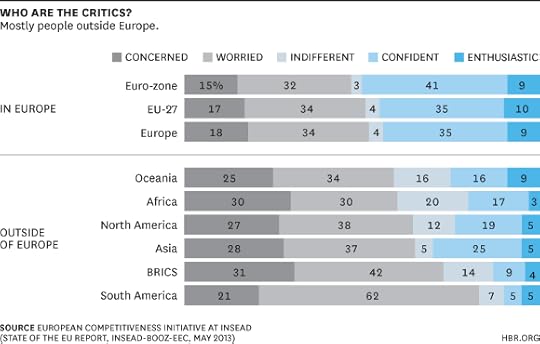

And who exactly is doing the complaining? The Europeans themselves seem to be pretty evenly balanced on the state of their Union. Outside Europe, though, opinions are distinctly less positive. A shocking 83% of Latin American respondents expressed concern for Europe’s future and nearly three quarters of those surveyed in the big emerging economies like China and India felt the same way. Nearly two thirds of North Americans were pessimistic.

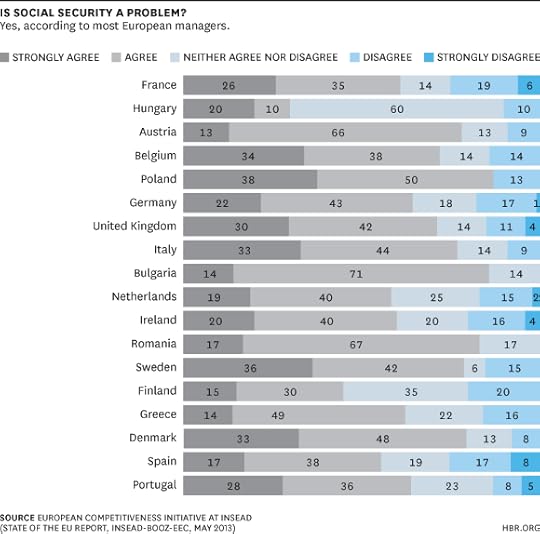

While they’re somewhat comfortable with innovation, European managers are worried about their overall competitiveness, which they feel is compromised by large, expensive and rigid social systems and labor markets, that are almost impossible to reform.

There’s some variation on just how deep the concern is. Hungarians don’t seem particularly troubled by the question but the Austrians, Belgians, British, Italians, Swedes, Danes, and Romanians are very concerned by it. The rest are not quite so worried but generally agree with the proposition that their countries’ inability to reform makes them uncompetitive.

But is all this negativity really justified? A seemingly contradictory message is emerging from other surveys and analyses that I and my colleagues at INSEAD and across partner institutions such as the World Economic Forum, Harvard or Cornell conduct for the Global Innovation Index Report (GII), the Global Information Technology Report (GITR), and the Global Talent Competitiveness Report (GTCI).

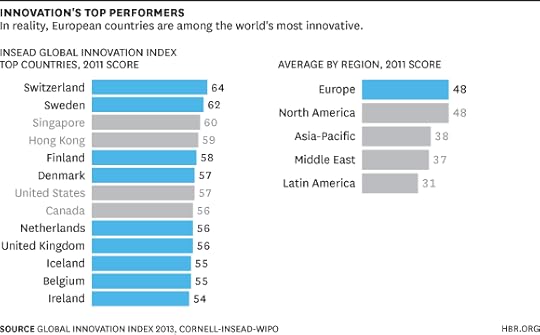

Let’s look at innovativeness. The data that goes into creating the Global Innovation Index is based on some 84 variables, covering over 140 countries. It gives us a reasonable sense of how successful at innovation different countries and regions are.

The US is usually seen as a hotbed of innovation. And it is certainly in the top ten. But in 2013 it was comfortably beaten by Singapore and Hong Kong and by four other countries: Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland. What’s more, the countries just below the US and Canada are all European as well. Of course, not all the European countries are as successful as those listed here, but on an aggregated regional level, we find that Europe is just as innovative as the US, and that both are well ahead of the other world regions.

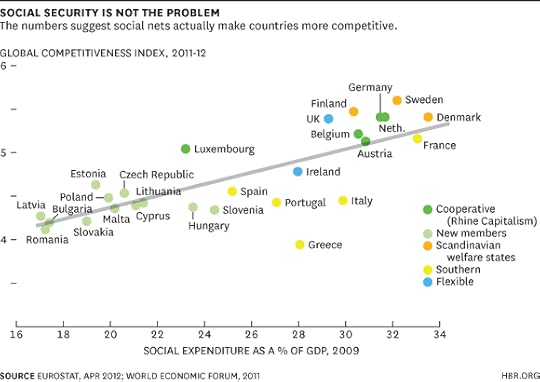

And what about those anti-competitive social systems? Take a look at this chart, which plots country competitiveness scores as per the Global Competitiveness Index against the proportion of GDP spent on welfare. Strikingly, the most innovative countries all spend a lot on the social safety net. Of course, correlation is not causality, but it does at the least suggest that social protection and competitiveness are not mutually exclusive.

So is Europe really sick? Maybe, but not perhaps in the way we think, and very possibly it’s at least somewhat psychosomatic.

February 11, 2014

The Eight Phases of Brand Love

“I really think of Diet Coke as my boyfriend.”

A wave of laughter hit the focus group observation room that was so loud that I’m sure the respondents could hear us on the other side of the 2-way mirror. Did that woman really say she thought that Diet Coke was like her boyfriend?

Commitment, intimacy, dependability—she felt all of these, not about Diet Coke, but from it. She loved it as a constant companion, a support mechanism and a celebratory friend. At the time, I thought this was preposterous. We can’t connect with products the same way we connect with people!

But I’ve since learned that in many important ways, that is just what we do. Academic study after academic study has proven it. We don’t just consume or interact with brands. We actually engage in relationships with them.

Relationships have natural stages – from our initial meetings all the way up until the relationship’s decline or demise. Where is your brand in its relationship with the consumer? Let’s briefly look at each stage:

Know yourself - The consumer relationship starts with the brand. Before you even meet the consumer, you must fully understand your brand. If you don’t know who you are as a brand, and what makes you different, better, and special, how do you expect a consumer to? You must clearly define a brand’s product benefits to set up more intimate, emotional bonds. It is these emotional bonds that will form the basis of a lasting consumer relationship.

Know your type – Every brand has an ideal consumer-someone who, when they connect with the brand, feels that that brand was made for her. The trick for marketers is to identify that ideal consumer, her functional, emotional, and social needs, and perfect the match between those needs and what your brand offers. For example, the brand team of a small regional beer, Dos Equis, went to the bars that their consumer, socially active males, frequented and spent night after night with them. They discovered that these guys’ biggest fear was to be seen as boring. Consequently, the “Most Interesting Man in the World” campaign was born and became a sensation, even being spoofed on Saturday Night Live. The result was a transformation of Dos Equis from being a small regional beer to the 6th largest beer in the country.

Meet memorably – The first few meetings between brand and consumer dictate whether the relationship has potential or whether it remains in the mere acquaintance phase. It is essential that we establish connections that are so special and memorable that a consumer desires to keep coming back for more. When entrepreneur Janie Hoffman launched Mamma Chia, a unique health beverage comprised of chia seeds floating in a jello-like texture, she knew she would have to educate the consumer. So, she went into the right environment, Whole Foods stores, and personally shared stories about the power of chia seeds. Hoffman went on to be named BevNet’s 2012 Person of the Year for the creation of “an entirely new beverage category.”

Make it mutual – When we are excited about our own relationships, we want to tell the world. With consumers and brands, it is no different. In this stage, we need to identify our category’s influencers, those consumers’ whose advice is sought out, and encourage them to spread our message to others. We can do this by providing them a rich experience with our brands. Time after time it has been shown that a positive brand experience trumps more passive brand engagements such as traditional advertising or social media in generating effective word of mouth.

Deepen the connection – At this stage, the bond with our consumer is so strong that they feel that the brand is “a brand made for me.” This is the commitment stage, where the brand and consumer relationship has hit its peak – the brand continues to romance the consumer and the consumer stays loyal to the brand. The emergence of a brand community, like the ones created by ardent fans of Disney or Harley Davidson, becomes a measurement of the depth of connection between brand and consumer.

Keep love alive – All relationships go through “ruts.” As the brand and consumer relationship matures, it is essential to “keep the spark” going by rejuvenating the relationship through innovation and news. The Apple brand is almost 40 years old, yet continues to be perceived as cutting edge. Why? Apple is always evolving, creating an ongoing stream of new products and innovations. And the apps designed by third-party developers help keep their products fresh in between launches.

Make up – Just like our own relationships, brands and consumers go through crises. This can either be a slow developing issue over time or a sudden, dramatic event. How a brand responds to a relationship crisis will dictate whether it reenergizes its relationship with the consumer or sends it into a tailspin. Cheerios’ decision to stop using GMO ingredients in its base brand not only brought back consumers who had left, but reenergized its existing consumer base by providing brand news.

…Or break up – Relationships end. We either recalibrate our existing brand and start engaging with a new consumer group or we fail forward, eliminate the brand, and use the lessons to develop consumer relationships with different product/service offerings. When Coca-Cola decided to ditch the disastrous New Coke, they used what they learned from that painful experience to help launch Coke Zero. Rather than replacing the existing brand of Diet Coke, they simply decided to offers two sugar-free colas.

And that enables the young woman who sees Diet Coke as her boyfriend to remain very, very happy.

Tackle Conflicts with Conversation

My husband and I got married after only three dates. Three weeks after the wedding, we had our first fight. An extreme conflict avoider, I packed my bags and walked out. Rich chased after me. “Turn around,” he said. “Let’s sit down and have a conversation. There are two things we have to learn to do — one is to fight, the other is to make up.” We’ve now been practicing both for 44 years.

Effective leadership, like a good marriage, hinges on how you deal with the tough stuff. But addressing and resolving conflicts requires enormous mental and emotional strength, which is why many of us try to avoid it. When confronted with a problem or dispute, we either move away (flee the scene, rely on others for resolution), move against (quietly using positional power to quell opposing arguments) or move toward (make nice, give in). This is natural. We instinctively want to avoid the risk of loss and social embarrassment, to stick with our points of view, to preserve relationships and the status quo.

But all three strategies are wrong-headed. When you fail to engage with a conflict, you can’t gather the input you need to find a workable solution. And it hurts your image as a leader. Take Sarah, the head of IT at a global technology company. Her job was to develop new engagement technologies in her organization, but instead of embracing critical feedback on her ideas, she ignored it. When people challenged her, she would simply reiterate her points, smile, nod and move onto something else as though the issue had been resolved, leaving everyone frustrated. Team members and colleagues began to see her as a conflict avoider, and she lost their trust.

So how does someone like Sarah learn to embrace, rather than avoid, disagreement? Through my executive coaching work (and my own experience), I’ve developed a few conversation-centered techniques that help.

Clarify the conflict by talking through each party’s stance. For example, “You seem to be suggesting that we really need to focus on elevating our gross revenue before we invest in a new IT strategy. Is that right?” or “It seems like we’re envisioning two different levels of risk. Tell me more about what you’re seeing as the downside.”

Consult a neutral friend or colleague. Discussing the problem with someone else will make it seem smaller. The social interaction will also put you in a more collaborative, connected state of mind.

Reframe, refocus, and redirect the conversation. Use the conflict as a springboard to find common ground. Say something like, “Let’s leave this aside for the moment and think about another way to approach the issue.”

All the companies I work with have checklists of behaviors their leaders need to thrive at the top. Chief among these are courage, resilience and agility in the face of change. There’s no question that an ability to manage conflict is part and parcel of all three. So the next time you’re faced with a situation in which positions are hardened and disagreement seems inevitable, don’t avoid it. Engage in conversation, and tackle the conflict head on.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

What Would Make You More Satisfied and Productive at Work?

Doing Less, Leading More

Successfully Integrate Your Work, Home, Community, and Self

Try Meditation to Strengthen Your Resilience

Is Your Innovation Problem Really a Strategy Problem?

Sometimes, the problem that we think we’re solving isn’t the real problem that we face.

I was running a workshop with a multinational engineering firm when I ran into a perfect example of an air sandwich, which illustrates this point. This dangerous obstacle to innovation is described by Nilofer Merchant in The New How as “the empty void in an organization between the high-level strategy conjured up in the stratosphere and the realization of that vision down on the ground.”

The firm is facing some challenges. Much of the work in their industry is becoming commoditized, and their margins have been shrinking. Furthermore, the amount of work they were winning dropped off significantly during and after the global financial crisis.

They have responded to these changes in their competitive environment and have started to position themselves as the most innovative firm in their market. But because the industry’s margins are so low, this strategy carries real risk. Backing up this claim will take significant investment to build the skills they need.

And yet the potential rewards are also significant. If they do become the most innovative firm in their market, they will be able to build long-term relationships with clients instead of transactional ones, charge a premium because they deliver better work, and possibly even start winning work outside of the bidding process.

I’ve been teaching innovation courses to groups of their both their senior and future leaders for a couple of years now to try to help them build this innovation capability.

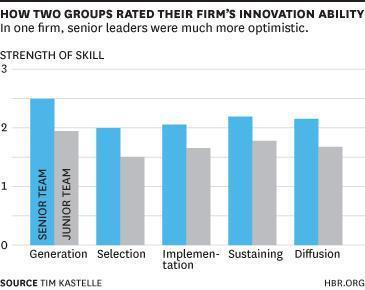

The chart below shows the responses to a questionnaire I administered called the Innovation Value Chain survey, and it demonstrates what an air sandwich looks like in practice. The bars reflect how two teams of managers, a senior team and a junior team, rank this firm on the five stages in the innovation process – idea generation, selection, and implementation, as well as sustaining innovations and diffusing them. Higher scores on the scale of 1-3 mean that they believe they are stronger in those areas.

This is a fairly typical profile of innovation capability within a large firm. They are very strong at generating ideas. Their weakest areas are idea selection and implementation, and they are adequate at sustaining ideas (keeping internal people engaged throughout the process of making the idea real) and diffusing the new ideas more widely. (One good sign: if you rank the five skills from the strongest to the weakest, the two teams have identical lists despite the gap between the two teams’ scores.)

So why does the senior team rank the firm a lot higher than the junior team in all five areas?

I’ve gotten a few different suggestions in response to this question, including:

The senior team is delusional. They believe that they have great innovation capabilities, but this is not true on the ground.

The junior team is ignorant. It might be that they simply don’t know what’s going on inside the firm.

The scores reflect differences in autonomy. The senior team might be more optimistic because they have more control over the process.

In this case, I think all three answers are partly true. The junior team didn’t know about a major R&D initiative that the firm was undertaking. And there are clear differences in autonomy: When the junior team gave presentations to some of the senior team outlining their ideas for improving innovation, the results were not good – the senior bunch shredded the ideas. This tells me that their perception that the senior team is out of touch with front-line realities is probably pretty close to accurate.

The problem with an air sandwich like this that it can kill an innovation initiative before it even gets started. Gaps like this between those that formulate strategy and those that execute it will make it incredibly hard to implement new ideas. This is one of the reasons that it is almost impossible to just add some innovation into an organization, without changing the culture.

Merchant’s argument is that the best way around this is to develop systems that allow strategy to be created collaboratively. She writes:

“The same few problems crop up, over and over again. We limit participation in strategy creation based on title and rank rather than relevant insight. We insist on lobbing strategy over the wall to the execution team without creating a shared understanding of what matters and why. And we reward individual accomplishment because it is easier than rewarding co-ownership of the ultimate outcomes.”

There are three key points to this story:

Top-down strategy is dangerous. When one group creates the strategy and expect another bunch to implement it, the result will be an air sandwich. The consequences of this are that strategies that may be great on paper die on the ground. Expanding the number of people that contribute to strategy creation is one good way to avoid this problem.

Innovation and strategy are tightly linked. Merchant is focused on strategy creation, but the same issues are true for innovation. Innovation works best when everyone in the firm is involved with creating and executing the ideas that will drive the firm to success.

Our problem isn’t always obvious. The firm right now thinks that they have an innovation process problem, but they’re really facing a strategy problem. If they change the way they make strategy, they will start to get different innovation outcomes. And that will make it easier to realize their strategy.

Making changes like this is never easy. The firm faces significant challenges. And their ambition is to re-make their industry – a bold, yet risky goal. They can improve their chances of reaching it not just by improving their innovation skills, but also by getting more people involved in creating their strategies and plans.

First, they need to get rid of that air sandwich.

The Unexpected Benefits of Rapid Prototyping

I had the great pleasure of hosting my dear friend David Kelley for a talk and on-stage conversation at the Rotman School last week. Apart from designing objects like the first commercial mouse, David is famous for being one of the earliest proponents of user-centered design and for being the originator of the concept of rapid, iterative prototyping. Like his iconic products, both methods are acknowledged home runs, but I have always believed the second to be a bigger contribution to the field.

Interestingly, a great deal of the value that comes from prototyping was probably unintended. Although much of the method’s success in producing designs comes, as David expected, from getting repeated input from potential product users during the design process, even more value comes out of the superior experience for the designer’s client (whether an external organization for a design firm or an internal business partner for a corporate designer) that the process delivers.

As I’ve written before, one of the biggest challenges facing designers is that they struggle to get their clients to adopt their design ideas. They hit a ‘prove-it’ wall: their clients ask for evidence that the design will succeed. The more radical and bold the design, the bigger a problem this is for the frustrated designer.

Here is where rapid prototyping comes in. During each iterative test of the emerging prototype with the user, the process generates little bits of data that the client can see and gain confidence from. The client will see the reaction of the users become ever more positive as their feedback is incorporated into the next iteration and the next and the next and the next. The client can’t help becoming more confident in the design as the users become more pleased.

The process provides both forward-looking designers with guidance in creating new ideas and and their clients with proof of concept. It effectively generates input data from the immediate future, embodied by the prototype users, that then becomes legitimate historical data by virtue of that immediate future being experienced by the user. If you’ll forgive the hyperbole, the data is a bit like light: both a wave and a particle.

David himself focused on the relationship between designer and end-user, and, as far as I can tell, did not consider the impact of a design process on the relationship between designer and client. That’s not surprising: formal design education also focuses largely on the end-user relationship. But if the design discipline is to fulfill its lofty promise of helping businesses provide superior end-user experiences, it needs to think a bit more about how designers interact with their business clients, through whom they must work to reach the users of the products that they design.

Indeed, I think that the structuring of design processes that have this characteristic of supplying both a user experience and a client experience is an important design concept in itself, an idea that should form part of design school curricula. We could call it Intervention Design, the formal thought process of designing the intervention into a client organization in such a way as to simultaneously enhance both the quality and adoption probability of the eventual design. David’s pioneering idea is one such approach but I doubt that it is the only one. If Intervention Design became a core design discipline, it could over time dramatically augment the role of design in business.

Italy’s Government Unwittingly Helped Spread the Mafia to Northern Cities

One reason for the recent pervasive infiltration of southern-Italian crime organizations into the country’s northern regions is a government policy that punishes mafiosi by forcing them to resettle far from their home towns, say Paolo Buonanno of the University of Bergamo in Italy and Matteo Pazzona of Universidad Catolica del Norte in Chile. The Italian government assumed that if gangsters were removed from the south and immersed in the more-law-abiding north, they would reform; nearly 3,000 suspected criminals were resettled under the confino plan from 1961–1974. But these individuals acted as seeds in transplanting crime into formerly mafia-free areas, the researchers say.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers