Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1471

February 11, 2014

Star Performers Need Extra Affirmation After a Setback

There are two major reasons baseball has been such a boon to statisticians trying to measure human performance. First, sample size: the United States alone fields 30 major league teams — each with a 40-man roster — that play 162 regular-season games. Every game comprises hundreds of plays. Second, because of the way the game is designed, you truly can measure individual performance as well as team performance.

But researchers trying to crunch the numbers on how the rest of us perform at work — that is, assuming your work is not to hit a small round ball with a thin round bat — have a tougher time. So can you forgive them for going back to the ballplayers?

Jennifer Carson Marr of Georgia Institute of Technology and Stefan Thau of London Business School did just that to try to quantify how top performers handle setbacks. They studied all 199 non-pitchers (pitchers tend to skew sample sizes in irritating ways) who had undergone salary arbitration since 1974, when the process was introduced. In the U.S., baseball’s arbitration process is famously bizarre — the player comes up with a number, the team comes up with a number, and the arbitrator chooses one or the other. Compromises are not allowed. The result is a clear winner and, very definitely, a clear loser.

Marr and Thau’s findings: when players lost their arbitration cases, their performance suffered. And the very best players suffered the most. The mediocre players, by contrast, barely suffered at all.

Before you chalk this up to sulky stars or greenhorned rookies, remember: most of the players who are arbitration-eligible have played in more than 3, and less than 6, baseball seasons. In other words, they’re young players with some experience who have every incentive to perform at a high level and prove they’re worth more money. And unlike in other sports, where salaries are capped, the riches to be had if you’re one of baseball’s top players are still mind-bogglingly massive.

So why would top performers perform worse after an arbitration loss? And, if it is the loss of status that gets under their skin — as the researchers theorized — how could this be prevented?

To find out, Marr and Thau ran a couple of behavioral experiments on a few willing students. Again, the loss of status hurt performance — but this time, they found that the effect was mitigated when the students were assigned a self-affirming task (in this case, writing about someone who made them feel respected).

Professor Marr tells the Academy of Management, whose journal is publishing the paper in their February/March issue, that there are three main lessons here for top performers:

First, take a break after a setback. You might be tempted to redouble your efforts, but chances are that you’re just going to end up making a bunch of mistakes.

Second, focus on something — outside of work — that makes you feel good about yourself. Many stars identify strongly with their jobs (that’s what helps make them stars), but after a loss of face, it’s the stuff we’ve got going on outside of work that will cheer you up — relationships, hobbies, and so on.

Finally, acknowledge that the hit to your ego is only temporary. You — like so many great sluggers before you — will get over it and come back.

This and previous research also indicates a couple of things managers can do to help their stars, both before and after a loss of status:

Praise them for working hard — not for achieving great outcomes or for “being smart.” Well-known research by Carol Dweck found that children who were praised for their hard work and their process were more resilient and took more risks than children who were praised for innate intelligence or “getting it right.”

At review time, look at the sum of their performance — not the mean. A mistake most of us make is taking the average of another person’s skills so that, for instance, if you tell me you are fluent in Chinese, English, and French, and know a little bit of German, I will actually judge you more harshly than if you’d just left out the German. As a manager, resist this urge.

Or, as Marr and Thau suggest, just give your star a break after she’s bungled something or lost face. Help her regain her status by letting her know that you value her work.

February 10, 2014

Use Co-opetition to Build New Lines of Revenue

Examples of high-profile failed business collaborations are everywhere. From the WordPerfect-Novell acquisition that led to bankruptcy, to the misfires of the Target-Neiman holiday experiment, it’s clear that despite the plethora of management literature on how to launch a successful partnership, collaborations often go bust. It turns out, where there is money to be made, self-interest prevails, thus trumping cooperation in the process.

Traditional collaborations fail because deep down, stakeholders assume their success must come at others’ expense, which is clearly a zero-sum game. The way forward is co-opetition, in which entities in the same industries act with what everyone recognizes as partial congruence of interests.

As management professors Adam M. Brandbenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff have written in their book Co-Opetition, businesses that form co-opetitions become more competitive by cooperating. For example, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, who practices co-opetition by partnering and competing with headhunters, said in a New York Times article, “[No] one can succeed by themselves. The only way you can achieve something magnificent is by working with other people. There [are] lots of co-opetitions.”

Unlike traditional collaborations, instead of coming together to do something and pretending you’re not competing, co-opetition leverages your competitor’s strength in order to thrive together. Recruiters use LinkedIn to find prospective candidates and employment opportunities, and, in order to increase product-users, LinkedIn relies on recruiters to use their professional networking platform — while each group would surely like a greater percentage of the recruitment pie for themselves, the pie as a whole is larger because of the involvement of both. So – how do you protect your own interest while cooperating with your competitors in order to create (and maximize) value?

Agree to share information. Sharing information and expertise is a great way to build trust with your competitors. One example is a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), a non-legally binding partnership, like the one Ford entered into with Toyota. They’re now talking about joint ventures to develop a lightweight-hybrid truck. In order to avoid getting burned, they’re taking it slow. As with any relationship, as it progresses you’re inclined to share more. When information-sharing is profitable for both partners, you can see some pretty strange bedfellows. For instance, Microsoft and Apple developed a partnership that stunned the tech community, Apple licensed their mobile “look-and-feel” patents to Microsoft, but they have an anti-cloning agreement. Apple makes money through licensing and Microsoft gets help in their mobile development department. Developing memorandums or licensing patents are only some examples of how sharing information with competitors can link to greater success down the line.

Focus on building something new. Co-opetitions work especially well for businesses that create the “latest- and-most-gadgeted” technologies and innovations because R&D is expensive. For example, in the airline industry, American Airlines partnered with Boeing to retrofit“76 Next Generation 737s.”If these firms had not embraced the idea of working together, they would not have the fiscal resources and manpower to renovate and build new airplanes. When creating an expensive technology or service, go to your competitors and say: “We both make X, but we have limited resources, however. Your company is awesome at doing A. My company is awesome at doing B. If we configure AB, instead of just creating X, we can create X2.”

Choose partnerships where you each bring something different to the table. Bartering with a similar company – but not one that’s too similar — is the best way to leverage and create win-win relationships. For example, online retailer Wayfair (disclosure: I used to work there) partnered with Amazon to leverage their brand recognition to increase sales conversions — and in turn gave them a cut of the profits. While Amazon and Wayfair are competitors, in this deal they both profit. In another example, Peugeot Citroen will supply Toyota Motors light-weight trucks to sell under the Toyota brand in the European market. Toyota, which had recently discontinued its own European light truck, will still have an offering for its customers, and Peugeot Citroen will have a market for its technology.

Businesses must account for the self-interest of others. In a traditional collaboration, you’re getting 1+1=2. In many circumstances, forming co-opetitions is better than traditional collaborations because they create transparency about motivations, agendas, and goals. So instead of asking, “What’s in it for me?” or “What’s in it for us?” … ask your competitor, “How can 1+1=3?”

New York’s Fashion Industry Reveals a New Truth About Economic Clusters

The week before Fashion Week in New York, now underway, is perhaps the busiest in the city’s apparel industry. Frantic designers rush around looking for gold buttons with blue inlay, for seamstresses to make pleats and for patternmakers with spare fabric. They make modifications to dresses in real time under enormous deadline pressures.

Yet when eyes eventually fall on the runways, they witness virtually glitch-less shows and talk-of-the-town creativity. How does New York’s fashion industry continually pull off Fashion Week year after year?

The answer lies in a complex economic system whose informal origins date to the mid-19th century and whose central idea rests on geographical proximity. We’re talking about the Garment District, eight blocks in Manhattan where designers, wholesalers, manufacturers, fabric sellers, button makers, and seamstresses all work.

The idea that highly specialized concentrations of an industry like the Garment District offer significant economic advantages is hardly revolutionary. The automobile, steel, mining and textile industries similarly occupied proximate physical space, sharing resources, labor and information to their great economic benefit. As the great economist Alfred Marshall observed in 1890, industries that clustered together generated economic growth by virtue of something “in the air.”

Exactly what is “in the air” in places like the Garment District? For a long time, discussions on the benefits of economic clusters, or agglomeration economies as urban planners call them, have been mainly theoretical or qualitative. Interviews, case studies and ethnographies tell us proximity matters to certain industries. Think Silicon Valley, Wall Street or Hollywood. Therefore, so the argument goes, cities ought to push policies that encourage the growth of spatially concentrated economic activity. But why — and how – these clusters work has remained a mystery.

To find out answers to these questions, we tracked 77 fashion designers working in the Garment District and the larger New York region over two weeks in July 2011. Using their cellphone data and a social-media tool we tracked their geographical movements and documented exactly where they went and when, compiling a real-time, minute-by-minute, day-by-day, snapshot of what they did. The designers voluntarily let us in on their activities – picking up a fabric, meeting with a manufacturer, grabbing a cup of coffee — by “checking-in” to Foursquare, a social media application that allows users to identify precisely where they are and what they are doing. To gauge the economic importance of the Garment District to the broader region, we studied the work lives of designers with offices in the district and those with addresses in New Jersey and the other boroughs. A majority of our sample worked outside the Garment District.

It turned out that the benefits of the district’s agglomeration economies were not confined to eight blocks in Manhattan, but spread evenly across the region. Having an office in the Garment District was not as important as the existence of the area itself. Seventy-seven percent of all trips the designers made were to the Garment District, and 80% of the businesses they visited were located there. Not only that, regardless of where the designers’ offices were located, they all similarly interacted with manufacturers, wholesalers and suppliers, spending almost the same amount of time with them. The difference between Garment District-based designers and outsiders was a mere 10 minutes.

But what the designers actually did from 10 am to 6 pm (the hours most kept) revealed no set patterns. When we studied the timing of their trips to manufacturers, wholesalers or suppliers, we found no meaningful pattern, regardless of the size of the firm. Every day was a new day.

Herein may lie the magic – what Marshall said was “in the air”– of economic clusters and their importance to cities. All designers need the same basic materials and labor to make a dress. But how they individually pursue and use those resources — and how they respond to the changing demands of realizing their conceptions — is a key component of their creative process. The Garment District’s agglomeration economies foster the freedom necessary for creativity to thrive, which is part and parcel of how great dresses are made in the first place. What we think is raw creativity – the electric energy of Marc Jacobs and Anna Sui or the exciting parties reported in the media – is quite a practical matter.

The great urbanist Jane Jacobs once remarked that “diversity is natural to big cities.” Her point was that the intermingling of different firms and industries that work together to produce things and ideas is a central feature of an urban economy and accounts for its ongoing vibrancy. And our study shows that this sharing is much wider geographically than previously thought.

Creativity and its economic impact – whether producing a wrap dress or a semiconductor – is rarely an act of genius in isolation. It instead is the interworkings and interventions of a highly efficient and effective cluster of firms and those who work for them.

This phenomenon unfolds in particular places, and those special places must be preserved if we want to keep our cities bright and our industries innovative. Let that be a lesson as we watch the runways and the flashing lights.

All video and images courtesy of Sarah Williams and Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, with the data visualization help of Georgia Bullen.

Eight Essentials for Scaling Up Without Screwing Up

Back in 2006, my colleague Huggy Rao and I launched an executive education program at Stanford called “Customer-focused Innovation.” Mornings consisted of lectures and case studies in a traditional classroom in the Stanford Business School; this was the “clean models” part of the program. In the afternoons, we moved the group to the (then) new Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, or “Stanford d.school,” for the “hands on” part. That midday transition could be jarring. The d.school was in a crowded, messy, and rather run-down double-wide trailer in those days. And then there was the fieldwork. That first year, the d.school team (led by Perry Klebahn) sent the executives out to observe and interview customers in BP gas stations. Their assignment was to prototype solutions to problems they heard about, revise them in response to user feedback, and then present them to a demanding group of BP executives.

For our part, Huggy and I were also hearing about problems every day – our students’ – and we got the idea to start working on our own prototype solution. We noticed that, no matter what we asked those executives to do – discuss a Harley Davidson case study, come up with ways to kill bad ideas, design solutions to improve that gas station experience – they came back to the same gnawing concern. Maybe it was somewhat hard to come up with a good, new solution, but the really hard thing was, once they landed on that better way, to get it to spread. This was the challenge that pervaded their comments and questions.

They described it as the biggest obstacle to building a customer-focused organization. The executives could always point to pockets in their organizations where people did a great job of uncovering and meeting customers’ needs. There was always some excellence – there just wasn’t enough of it. And what drove them crazy, kept them up at night and devoured their work days, was the difficulty of spreading that excellence to more people and more places. We started calling it the Problem of More. They usually described it as the challenge of “scaling” or “scaling up.” And they emphasized that the problem wasn’t limited to building customer-focused organizations; it was a barrier to spreading excellence of every stripe.

So Huggy and I started taking a harder look at scaling as a class of problems that might be addressed by a common toolkit. We examined the Problem of More as it was faced by a wide range of organizations: Google, Facebook, the Girl Scouts, Kaiser Permanente, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Procter & Gamble, JetBlue Airlines, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (now part of Pfizer), Taj Hotels, IKEA, the Transportation Safety Authority (TSA), start-ups including Citrus Lane, Pulse News (now part of LinkedIn), and Bridge International Academies (a for-profit chain of nearly founded in 2007 that now operates some 200 highly standardized schools for poor children in Africa), and on and on. And once people heard we were trying to make headway on all this “scaling stuff,” they gave us their ideas – and peppered us with more tough questions.

Thus went the seven-year exercise in iterative prototyping that resulted in Scaling Up Excellence: Getting to More Without Settling for Less. The same common themes popped up again and again — and led us to identify the key beliefs, skills, and actions that are hallmarks of effective scaling. And to sum all this work up in the fewest words, here they are:

Understand that you are spreading a mindset, not a footprint. Scaling requires instilling the right beliefs and behaviors in people, not just running up the numbers as fast as you can.

Approach scaling as a problem of both more and less. As an organization or program expands, traditions, strategies, practices, and roles that were once helpful outlive their usefulness, creating friction and frustration. They must be streamlined or eliminated.

Consider where you want to be on the Buddhism-Catholicism continuum. That is: do you concentrate on making people true believers, then let them localize the rituals as much as they like – or do you legislate the behaviors you’ve identified as best, assuming they’ll act their way into a state of believing?

Link hot causes to cool solutions. Making a rational argument for a change isn’t usually enough to instill a new mindset and unseat old habits. The most effective campaigns stir up “hot” emotions in people (pride and anger are especially effective) and then channel that energy and passion into “cool” (clear and step-wise) actions.

Connect people and cascade excellence. Exposing people to a conference, a few speeches, or a bit of training isn’t enough to fuel scaling. It requires building or finding pockets of excellence and, in turn, using them to guide and inspire the creation of more such pockets.

Cut cognitive overload, but embrace necessary organizational complexity. As the cast of characters in an organization or program grows, coordinating all those people and sustaining healthy social bonds among becomes more difficult. The trick, and it is a difficult one, is to add just enough complexity so that people can do their work, but not so much that “they feel as if they are walking in muck” as Twitter’s SVP of engineering Chris Fry puts it.

Build organizations where people feel “I own the place, and the place owns me.” Scaling starts and ends with individuals. Effectiveness spreads and sticks when people feel obligated to live the right mindset and equally compelled to hold others to the same standards.

Go from bad to great. To clear the way for excellence to spread, the first order of business is to clear away destructive beliefs and behaviors. Indeed, a big pile of academic studies and business cases show that “bad is stronger is stronger than good.”

Many of these lessons, Huggy and I would be the first to admit, could be books in themselves – and all deserve their own blog posts. In fact, the hyperlinks in the list above indicate topics about which I’ve already written on HBR. I’ll try to cover them all eventually, so check back from time to time. If you’re like most of the managers I’ve met since 2006, you are probably knee-deep in the challenge of identifying excellence and spreading it to more people and places – and we can all keep learning from each other.

Basecamp’s Strategy Offers a Useful Reminder: Less Is More

Unless you follow tech companies, you might have missed the startling announcement by collaboration and communications software maker 37signals that it has decided to refocus the entire company on a single core product.

“Refocusing” might be an understatement. 37signals has developed a dozen different products and services since its founding in 1999. They will now be a “one product company” focused on Basecamp, its popular project management software. To emphasize the point, the company is also changing its name to Basecamp. So instead of following the conventional wisdom about growth through diversification, CEO and founder Jason Fried is doubling down on one successful area and putting all of his resources in one basket.

Basecamp is a small company. Even with more than 15 million users, it still has less than 50 people on its payroll. So it’s somewhat audacious strategy might not be a model for everyone. But regardless of your company’s size, there’s a lot to be said for the power of pruning and the importance of maintaining focus. For many companies, in fact, the strategy of “less is more” has been a powerful driver of success. For example, one of the secrets to Trader Joe’s profitability (which is one of the highest in its industry) is that they only carry 4,000 stock keeping units (SKU’s) per store vs. the typical 50,000 at other grocery chains. They also open a limited number of stores each year, trading off rapid growth for insuring the quality of their brand. Similarly, Apple has maintained the dominance of the iPhone partly by resisting the urge to create multiple product variations with different functions and features, in stark contrast to their competitors.

Keeping a business focused on a limited number of products, customers, or capabilities is not a new idea. In the 1950’s, Peter Drucker emphasized that business strategy needs to include “purposeful abandonment,” i.e. deciding what not to do. Similarly, Peters and Waterman’s 1982 classic, In Search of Excellence, reported that successful companies were those that could “stick to their knitting” and not get sidetracked.

Despite all of this advice, the kind of radical focus exhibited by 37signals (now Basecamp) is difficult for managers who often act like kids in a candy store. Instead of focusing on doing a few things well, they try to go after too many customer segments, too many adjacencies, and too many new technologies. Witness the struggles of financial services firms that become too big to control effectively; or large pharmaceutical companies that place bets on so many therapeutic areas that they don’t end up winning in any of them.

It’s a natural human tendency to want to do more. Most of us have trouble walking away from tempting opportunities, whether it’s at the dinner table, or at work. So we end up with indigestion at home and overload at work. That’s why it takes a great deal of discipline, and even courage, to slim down, both physically and strategically.

A case in point is Google’s recent sale of Motorola Mobility to Lenovo. The original purchase was probably a tempting opportunity that was viewed as too good to miss; but when it became clear that the telecommunications hardware business was not in their sweet spot, Google’s senior executives made the tough decision to sell, despite the financial consequences. And in the long run, avoiding distraction and dilution of focus will probably be worth the cost.

Most of us of course are not in the position to buy and sell companies or even rationalize our product lines. As managers however, we can make sure that our teams stay focused on the few critical strategies and projects that will make the most difference. We also can ask Drucker’s question about what we should stop doing; and we can push back on others when we’re asked to do things that might be distractions from the core mission of our group. None of this is easy in the midst of day-to-day pressures. But in the long run, it’s very likely that we’ll reap higher rewards by doing less.

Protect Your Brand From Cybersquatting

Right now, we are witnessing what an executive at the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) called “the biggest change to the Internet since its inception.” As ICANN begins launching new generic top-level domain (TLD) extensions, we’ll no longer be limited to addresses ending with .com, .net, and other already familiar TLDs. We’ll see .clothing, .food, .sport, and many, many more. Some people are hailing the new launches as a huge win for consumers, while others decry the oncoming juggernaut as a to the rights of brand owners. The scope of this TLD launch, its reception by the internet community, and, ultimately, its success or failure all remain to be seen. What is certain is that businesses, brand owners, and other stakeholders need to be informed of these changes and take steps to prepare themselves.

It might surprise you to hear that, even prior to this current expansion, there were 21 generic TLD extensions in place. The domain space was expanded by ICANN in the mid-2000s to include various extensions that turned out not to be very popular, such as .jobs and .mobi. But now, ICANN is working in partnership with various stakeholders to allow for the creation and delegation of what many say will be hundreds of new TLDs. Over the next few years, we can expect TLDs to incorporate generic terms like .book, .clothing, and .diamonds.

Allowing these new TLDs will give many companies and individuals better options for registering their marks, names, and other designators as second-level domain names (to the left of the dot). For example, imagine that Bob owns a business in Boston called Vintage Clothing. In setting up its original website, he was disappointed to find that vintageclothing.com was unavailable and even bobsvintageclothing.com was taken, so he settled for bobsvintageofboston.com. Now, he has the chance to register bobsvintage.clothing or even vintage.clothing.

The problem, of course, with more naming options is more opportunity for cybersquatting. Thus there is tension between the benefits of more domain extensions and the threats to trademark owners’ ability to protect their marks from infringement. Here’s what you should know about how ICANN hopes to prevent and fight cybersquatting and infringement, through the establishment of two rights-protection mechanisms:

The first is a system that enables trademark owners to pre-register domain names under each new TLD that correspond to their registered trademarks. The mark owner must first submit proof of its rights to an entity ICANN created, the Trademark Clearinghouse (TMCH). Once those rights have been verified by the TMCH, the mark owner will be eligible to register domain names that are an identical match to its registered mark during “sunrise” periods — periods of at least 30 days before registration for a given TLD is opened to the general public. This process is designed to give brand owners a key advantage over potential cybersquatters trying to register infringing domains.

Sending proof of rights to the TMCH provides an additional benefit to brand owners. If someone attempts to register a domain name during the general registration period under any new TLD, the mark owner will receive notification of the attempt, and the registrant will be shown a cautionary notice that their registration may violate the brand owner’s trademark rights. The domain registrant can still proceed with registering the domain, as there is no automatic blocking. However, they will have been put on notice, which could help the brand owner’s case in a later challenge to that domain registration.

Brand owners should be aware that there is an annual fee to use the TMCH, and they will also be charged a fee set by the registrar to register any domain names during the TLD sunrise periods.

A second rights-protection mechanism implemented by ICANN is the Uniform Rapid Suspension (URS) system, a mechanism through which brand owners can contest the registration and use of a domain name that is identical or confusingly similar to its trademark.

The URS is designed to be a speedy and cost-effective proceeding, with a shorter duration and significantly lower filing fees than current domain dispute remedies such as the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP). Although not appropriate for all disputes, the URS can offer brand owners some significant advantages when used as part of an overall brand-protection strategy.

As with the current UDRP, adjudication of a URS dispute is handled by an authorized dispute resolution provider. Unlike the UDRP, however, a successful URS complaint will result only in the challenged domain name’s suspension, termination of the registrant’s control over the domain, and the disabling of any website or other services or content associated with the domain name. The URS will not provide for transfer of the disputed domain name to the trademark owner, and the brand owner will not be permitted to use the domain name while it remains in suspension during the duration of its registration term. If the brand owner wants to take ownership of and use the disputed domain, it should instead pursue a UDRP proceeding or other legal action. The essence of the URS, which is designed for clear-cut cases of cybersquatting where there is no genuine dispute over the facts, is in its speed and simplicity.

In addition to the URS, trademark owners can also utilize the currently available UDRP and litigation in federal court under the Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act to resolve domain disputes. Each of these available options provides for somewhat different relief, and the choice of which to select will depend on a variety of factors. Brand owners should consult with counsel to discuss which may be the best option for the particular situation.

The expansion of the domain name space will create new challenges, but it also presents positive opportunities for businesses and individuals to stake new ground online. Provided that you, as a brand owner, are aware of your options, you should be able to navigate the expansion to your advantage.

How a Firm’s Ethical Failure Can Increase Employee Satisfaction

If a company responds vigorously to a breach in ethics, workers who witnessed the breach end up more satisfied with the firm than if no failure had occurred at all (4.55 versus 4.22 on a seven-point satisfaction scale), according to a study of more than 24,000 employees in 16 U.S. companies by Marshall Schminke of the University of Central Florida and colleagues. But the researchers caution that anything less than an outstanding response on the company’s part leaves witnesses to ethical failures feeling less satisfied than nonwitnesses. Thus ethical failures represent an opportunity—often missed—for companies to enhance their relationships with their employees.

Don’t Persuade Customers — Just Change Their Behavior

Most businesses underestimate how hard it is to change people’s behavior. There is an assumption built into most marketing and advertising campaigns that if a business can just get your attention, give you a crucial piece of information about their brand, tell you about new features, or associate their brand with warm and fuzzy emotions, that they will be able to convince you to buy.

On the basis of this assumption, most marketing departments focus too much on persuasion. Each interaction with a potential customer is designed to change their beliefs and preferences. Once the customer is convinced of the superiority of a product, they will naturally make a purchase. And once they’ve made a purchase, then that should lead to repeat purchases in the future.

This all seems quite intuitive until you stop thinking about customers as an abstract mass and start thinking about them as individuals. In fact, start by thinking about your own behavior. How easy is it for you to change?

Consider your own daily obsession with email and multitasking. Chances are, you check your email several times an hour. Every time you notice that the badge with the number of new emails has gotten larger, you click over to your browser, and suddenly you are checking your emails again. This happens even when you would be better off focusing your efforts on an important report you are supposed to be reading or a document you should be writing. You may recognize that multitasking is bad and that email is distracting, but that knowledge alone does not make it easy to change your behavior.

If you are a company, you might think it would be easy to sell this person a solution to their problem. However, it’s not as easy as that – there are deeply ingrained habits here that won’t just go away.

Let’s go through some of what is required to create different habits. The point is to recognize how much work goes into changing behavior.

First, you have to optimize your goals. Many people err in behaviors like email by focusing on negative goals. That is, they want to stop checking their email so often. The problem with these negative goals is that you cannot develop a habit to avoid an action. You can only learn a new habit when you actually do something.

For marketers, this means focusing on how to get consumers to interact with products rather than just thinking about them. As an example, our local Sunday newspaper often comes in a bag with a sample product attached that encourages potential consumers to engage with products.

Second, you need a plan that includes specific days and times when you will perform a behavior. For example, many people find that they work most effectively first thing in the morning, yet they come to work and immediately open up their email program and spend their first productive hour answering emails (many of which could have waited until later). So, put together a plan to triage email first thing in the morning and answer the five most important emails and leave the rest until later in the day.

Now that many people have calendar apps that govern their lives, it gets easier to put things on people’s schedule to keep them engaged with a business. For example, services from hair salons to dentists can schedule appointments and send an email that links to Outlook and Google calendars.

Third, you need to be prepared for temptation. Old behaviors lurk in the shadows waiting to return. If you have an important document to read, and you know that you will be tempted to check your email, find a conference room in the building and use that as a home base away from your computer to get your reading done.

To keep customers from falling back into the “bad habit” of stopping off at the drugstore for oops-we-ran-out-of-it products like laundry detergent or diapers, Amazon makes it easy to schedule regular shipments right to your home. You never need to stop at the drugstore again – or even to remember to check how much laundry detergent is left in the bottle.

Fourth, you need to manage your environment. Make the desired behaviors easy and the undesired ones hard. If you want to avoid multitasking, then remove as many of the invitations to multitask from your IT environment. Close programs (like Skype) that have an IM window. Only open your email program at times of the day when you are willing to check email. Shut off push notifications on your phone when you have an important task to complete.

Marketers need to work with their designers to come up with packaging that encourages consumers to put the product into their environment. As I discuss in my book Smart Change, Procter & Gamble helped increase sales of the air refresher Febreze by redesigning a bottle that originally looked like a window cleaner bottle (and cried out to be stored in a cabinet beneath the sink) to one that was rounded and decorative (and could easily be left out on a counter in a visible spot).

Finally, you need to engage with people. Many people feel pressure to accomplish important goals alone, but there is no shame in getting help from others. Find productive people within your organization and seek them out as mentors to help you develop new habits.

The “positive peer pressure” technique is frequently used in service companies and organizations like Weight Watchers and Alcoholics Anonymous, but can be used by any business that’s trying to encourage repeat visits. For instance, a fitness center might offer a few free or discounted personal training sessions to new members to help them get in the habit of working out – and making them less likely to quit.

None of these factors works by itself. You need to create a comprehensive plan to change your behavior. Otherwise, the constant temptations to multitask will sap your productivity despite your best intentions.

This same set of principles applies for marketers. No matter how motivated consumers may be to try your product or service, or how unhappy they may be with their current situation, if you do not focus on a comprehensive plan for changing their behavior, then you are unlikely to have a significant influence on them.

Your business will not succeed just by trying to change attitudes and preferences. You will succeed by helping people to develop goals, create plans, overcome temptations, manage their environment and engage with others. You will influence your customers only when you give them as much support as you would need to change your own behavior.

February 7, 2014

CVS’s Lesson: Carpe Diem

When CVS/Caremark announced that it would forego some $2 billion in sales of tobacco and related products recently, CEO Larry J. Merlo stated that: “We came to the decision that providing health care and selling cigarettes just don’t go together in the same setting.” What he did not say, however, is how that laser-like focus on the company’s strategy also turned reputational risk into an opportunity. CVS is now one of a small group of companies that have realized that their reputation is the most valuable asset they have and that building a stronger reputation by avoiding risks to that reputation can create a significant competitive advantage. Let’s look at how these companies are protecting their reputation and brands while enhancing and realizing strategic value from them.

First, companies need to look into their business practices and ask two questions: What are we doing that we should not be doing? And, what aren’t we doing that we should be doing? A half-day session on these questions with your executive committee will usually uncover reputational risks that could easily lead to problems or even a crisis. For example, Coca-Cola uses an extraordinary amount of water to make the world’s top brand of soda with estimates ranging from four to 250 bottles of water per bottle of Coke. Before being attacked for behavior that could easily be labled unsustainable, the company teamed up with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) a few years ago in a project to put all of the water back that they take out. In other words, they plan to become water neutral. They then told this to the world in a co-branded ad with the WWF. They didn’t say how or when, but the commitment is clear and endorsed by a reputable partner. Similarly, McDonalds got rid of smoking in its restaurants ten years before any laws changed banning this activity. How do these companies come to such conclusions?

Here is how the conversation might have gone at CVS. Organizations like the American Cancer Society and the American Lung Association have been against the sale of tobacco in pharmacies for many years and municipalities in California and Massachusetts have started to put legislation in place that would ban the sale of cigarettes in a variety of settings including pharmacies. Given the risk that someday key constituencies and antagonists would start to focus on this problem more aggressively anyway, why not get out in front of the problem? And the benefits of doing so should be obvious from the outpouring of support CVS received with its announcement. From the White House to the American Lung Association, CVS has received kudos for what seems to be a focus on shared value with society rather than the reckless pursuit of revenue at any cost. This kudos lead to the unusual occurrence of positive publicity for CVS’s business in major media outlets like the New York Times and CNN.

But some senior executives have asked me where does it all end? CVS sells alcohol in some states, and also sells soda and food that some might say are as bad as cigarettes. Shouldn’t a healthcare company also worry about obesity? In addition, there is the matter of giving up $2 billion in revenue. CVS has hinted that it intends to find ways to make that money back, but the company could have done whatever it has planned, continued to sell cigarettes, and made even more money. That’s how most companies would have looked at the situation.

Finally, how can we calculate the intangible value associated with this rise in reputational capital for CVS? The fact is that we cannot easily measure, or even estimate what that might be without first tracking data across multiple constituencies for many years, and then doing some pretty heavy math and statistics that most of these companies know little about. Still, even without easily pinning a dollar figure to the intangible value of doing the right thing, we’re pretty certain that there is indeed real bottom-line benefit.

Our research and the research of organizations that have specialized in the measurement of reputation like Communications Consulting Worldwide that companies with a strong reputation have a price advantage: they pay less to suppliers, and can charge more to customers. They have a competitive advantage too in that they can get the best recruits to work for them, tend to have more stable revenues, face fewer risks of crisis, and when something bad happens they are given the benefit of the doubt by their stakeholders. And finally, highly reputed companies are more stable, which means they have higher market valuation and stock price over the long term and greater loyalty of their investors, which leads to less volatility.

So why doesn’t every company do what CVS did? Because senior managers tend to focus on the short-term operational and financial aspects of their companies rather than the intangible assets that are worth so much more. Because it is hard to argue with shareholders who will complain (as they did by reducing CVS’s stock price the day of the decision) that they aren’t getting the return on their investments fast enough. Because you can’t manage what you don’t measure, which means that while CVS could tell us how much they stood to lose, they couldn’t put a number on what they stood to gain by doing the right thing for their customers and for society.

When our alumni magazine, Tuck Today, recently asked several of us to think about what the future might hold for our various disciplines, I said that I envisioned a future where companies would be more focused on earning their reputation the old fashioned way by doing things we admire rather than things that are expedient. That managers would regularly ask themselves what they should stop doing because it would look bad on the front page of the newspaper someday, and that they would be willing to take risks for the long-term acquisition of a stronger reputation. CVS, I hope, has shown us the future.

Where Are All the Self-Employed Workers?

Along with a bunch of other, more headline-grabbing numbers, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported this morning that 14.4 million Americans were self-employed in January. Of those, 9.2 million were unincorporated self-employed workers and another 5.2 million were incorporated.

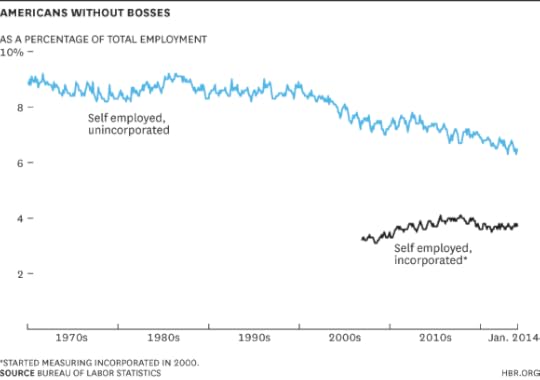

That’s interesting, given that back in January 2000 (which is as far as the BLS tally of the incorporated self-employed goes), the number of self-employed was … 14.4 million. Since then there have been some modest ups and downs, but overall no change. And as you can see in the chart below, the long-term trend in the percentage of workers who are self-employed actually appears to be downward:

But isn’t this the age of Free Agent Nation, as Dan Pink declared back in 1997? What about “The Rise of the Supertemp” that Jody Greenstone Miller and Matt Miller reported in HBR in 2012? Or “The Third Wave of Virtual Work” described by Tammy Johns and Linda Gratton last year in HBR, which has untethered knowledge workers from offices and made independent work more practical? It is as if, to paraphrase economist Robert Solow, you can see the age of self-employment everywhere except in the self-employment statistics.

Why is this? Two reasons, mainly. One has to do with definitions — the BLS standard for self-employment isn’t the only valid one. The second is really about history. We may well be witnessing the rise of a new kind of independent worker, but there have been different kinds of independent workers in the past. Far more of them as a percentage of the workforce, in fact, than we see today or are likely to see anytime soon.

Defining Independence

First, the definitions. The BLS gets its self-employment totals from the Current Population Survey, a.k.a. the household survey, a monthly quiz of 60,000 American households conducted by the Census Bureau (this is the same survey that generates the unemployment rate). Respondents are asked, “Last week were you employed by government, by a private company, a nonprofit organization, or were you self-employed?”

This either/or choice excludes a lot of people who are doing independent work on the side, or whose jobs are really more like gigs. A survey conducted for the past three years on behalf of MBO Partners, a provider of support services for independent workers, counts temp workers, on-call workers, and those on fixed-term contracts as “independent workers.” That gets the total to an estimated 17.7 million in 2013, up from 16 million two years before. “When you start throwing these other people in, that’s where the growth is,” says Steve King of Emergent Research, which designed the survey.

“The household survey is really good,” continues King. “I don’t think they’re missing people who are working; they’re just categorizing them using methods they developed in 1950. Changing that survey takes an act of God, because it messes up all the time series.”

So others are driven to adopt their own categories. The Freelancers Union frequently cites a number of 42 million independent workers, about a third of the workforce. It gets that from a 2006 Government Accountability Office report that said there were about 42.6 million “contingent workers,” meaning “agency temporary workers (temps), direct-hire temps, on-call workers, day laborers, contract company workers, independent contractors, self-employed workers, and standard part-time workers.”

Now, classifying all the nation’s part-timers as independent workers is quite a stretch. I’m not going to carp too much because it’s in keeping with the Freelancers Union’s noble aim of taking the lemons dealt by the labor market over the past decade-plus and turning them into artisanal lemonade. Plus, they could have rounded up to 43 million if they wanted to. But there aren’t 43 million truly “independent” workers in the U.S.; there are 43 million people who are working but aren’t doing it full-time for somebody else.

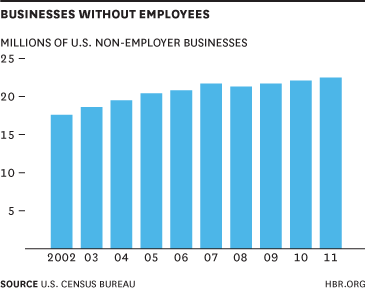

Another approach to the self-employment data paradox is to measure something completely different. Dan Pink, for example, pointed me to the Census Bureau’s annual tally of “nonemployer businesses,” which is taken from tax return data:

This seems like a realistic proxy for Pink’s Free Agent Nation, and it shows some actual growth, especially in the early years of the millennium. What it doesn’t show is the kind of explosive growth that advocates for the self-employed sometimes proclaim. MBO Partners, for example, predicted in 2011 that by 2020, “70 million people, more than 50 percent of the private workforce, will be independent.” Given that the actual research commissioned by MBO says that there are now about 17.7 million independent workers and the number has been growing at 5% a year, this was either a bold bet that the Affordable Care Act is going to drive/lure a lot more people out of full-time jobs than the Congressional Budget Office is predicting, or silly marketing hyperbole.

Still, one perfectly valid reason why some people persist in being very bullish about the rise of independent work in the face of some pretty unbullish overall statistics is that some kinds of independent work, among them the kinds probably most relevant to HBR readers, are in fact on the rise. They’re just not the only or even the main kinds of independent work out there.

Self-Employment Old and New

For the first century of its existence, the United States economy was dominated by independent workers. Most of them were farmers. Others were tradespeople, professionals, hands-on service providers, and such. Even after the huge economic transformations wrought by the first half of the 20th century, the self-employed still made up more than 19% of the workforce in 1949, according to the BLS, compared with just over 10% today. (The BLS data series on self-employment starts in 1948.)

Most of this decline has been due to the continued emptying and consolidation of America’s farms (or, if you prefer, the productivity revolution in U.S. agriculture). Self-employed farmers, ranchers, hunters, fishermen, and loggers made up more than 8% of the workforce in the late 1940s. Now it’s less than 1%.

It’s not just that, though. Other long-established varieties of independent work have been declining, or at least not growing much. Mom & pop stores, definitely, but also some other very large categories that may not immediately spring to mind. Doctors, for example, who have been reacting to the increasing complexity of their business by grouping together or joining hospital staffs. Sole-practitioner lawyers who are getting out of a field that seems to be in long-term decline. And real estate agents, contractors, and others who are dependent on a boom-bust housing sector which has been mostly a bust in recent years.

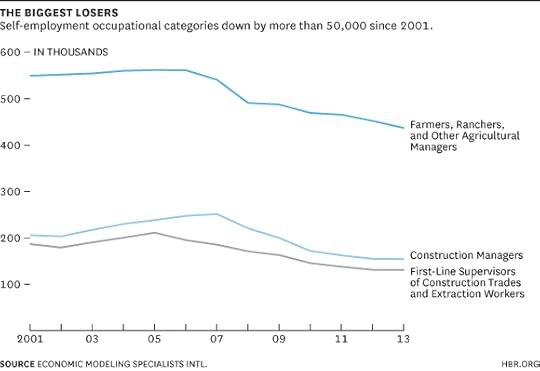

Here are the occupational categories that have seen the biggest declines in self-employment since 2001:

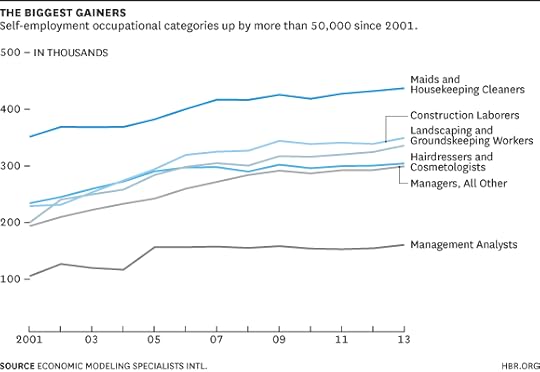

These numbers stem from data collected by the Census Bureau in the American Community Survey, a rolling census of about three million people a year that the House of Representatives voted in 2012 to defund (the Senate didn’t concur). The Census Bureau doesn’t publish these numbers in very user-friendly form, but Economic Modeling Specialists Intl., a subsidiary of CareerBuilder, gets the raw data, massages it with numbers from some other government surveys, and delivers a remarkably detailed portrait of what the unincorporated self-employed are up to. On Thursday, EMSI published a nice roundup of developments since 2006. They also sent me a spreadsheet with the numbers for every occupational category going back to 2001. Here are the occupations with the biggest gains in self-employment over that period:

This doesn’t exactly offer resounding support for the thesis of a boom in independent white-collar work. The world surely needs more landscapers and maids than management analysts, and it gets them. Also, some of those construction managers and first-line supervisors from the previous chart seem to have landed less-remunerated jobs as construction laborers in this one. “Management, other,” in case you’re wondering, is a grab-bag category of managers who can’t otherwise be classified as construction managers, purchasing managers, financial managers, etc.

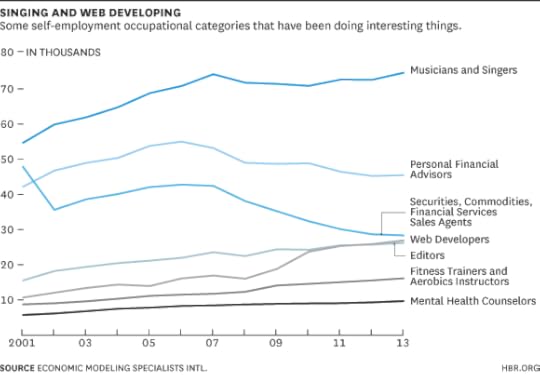

These numbers don’t, however, include the incorporated self-employed, who tend to skew toward higher-paid work. Also, the vagaries of the occupational categories used by the government can have a big impact. All the nation’s maids get thrown into one category; its physicians are split into at least nine. With a few days of work, I might be able to coax a clearer narrative from the data. Failing that (I may get to it later), I pulled out a few categories that grabbed my attention:

The boom in musicians and singers took me by surprise. Maybe this is one case where the Long Tail really has panned out for people. The two financial occupations both show the impact of the financial crisis, but it’s interesting (and I think heartening, from the consumer perspective) to see that the financial advisors are rebounding while the salespeople aren’t. With editors, the upward trajectory seems indicative less of a boom than a bust — the publishing industry has been shedding jobs for years, and now relies on freelancers more than it used to. But that does represent a shift to independent white-collar work, even if a lot of the people doing it would prefer a regular paycheck. The boom in independent web developers is of course exactly the kind of New Economy, Free Agent phenomenon we’ve been expecting to find. And the rise of fitness trainers and mental health counselors is indicative that there are hands-on independent service jobs on the rise that are more remunerative and presumably more pleasant than mowing lawns and vacuuming floors. (Dietitians and nutritionists and lots of different varieties of counselors, therapists, and psychologists are also seeing substantial gains.)

Sprinkled among the EMSI spreadsheet are other attractive-sounding (if not exactly giant) occupations on the rise: scientists of various kinds, human resources specialists, computer and information systems managers, technical writers, market research analysts, and so on. Free Agent Nation is out there, and parts of it are growing fast. It’s just not always easy to find, and by the looks of it still has a long ways to go before it takes over the rest of the nation.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers