Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1475

February 4, 2014

Thoughts of Fast Food Hinder Your Ability to Derive Happiness from Small Pleasures

Research participants who had seen a picture of a fast-food burger and fries subsequently rated themselves less happy upon viewing 10 photographs of natural scenic beauty (4.86, on average, versus 5.45 on a seven-point scale), say Julian House and two colleagues from the University of Toronto. Exposure to the idea of “fast food” makes people more impatient and impairs their ability to derive happiness from pleasurable stimuli; this effect could have a long-term negative effect on people’s experienced happiness, the researchers say.

CMOs and CIOs Need to Get Along to Make Big Data Work

A global telecoms company recently decided to do what many companies are doing: figure out how to turn big data into big profits. They put together a preliminary budget and an RFP that asked vendors to take the data the company had — customer call and payments behavior, online searches, social network activity, billing, etc. — and identify opportunities.

Vendors salivated at what essentially was a blank check to collect and analyze everything. Two months later, the bids were coming in 400 percent over budget. The solution? Cut back the scope. But no one was sure what to cut and what to keep because the goals had not been clearly enough defined. Months of wasted time and money later, the company is no closer to a big data plan.

Variations of this Big Data story line are being played out in executive offices around the world, with CMOs and CIOs in the thick of it. CMOs, tasked with driving growth, are pounding the table demanding that the surfeit of customer data their companies are accumulating be turned into increased revenue. CIOs, tasked with turning technology into revenue, are themselves pounding the table demanding better requirements for Big Data initiatives.

In all this table-pounding is a central truth in today’s Big Data world: both the CMO and CIO are on the hook for turning all that data into above-market growth. Call it a shotgun marriage, but it’s one that CMOs and CIOs both need to make work―especially given that worldwide, data is growing at 40 percent per year. To do that, both executives will need to change how they work―and how they work together.

“Most CMOs have woken up to the fact that technology is fundamentally changing what marketers do and we can’t treat IT like a back-office function,” says Jonathan Becher, CMO of SAP. “The CIO is becoming a strategic partner that is crucial to developing and executing marketing strategy.”

The pain of getting this relationship right is absolutely worth the gain. Companies that are more data-driven are five percent more productive and six percent more profitable than other companies. Given the $50 billion that marketers already spend Big Data and analytics capabilities, the pressure is on to show significant above-market returns for that investment.

The CMO and CIO are natural partners: the CMO has an unprecedented amount of customer data, from which s/he needs to extract insights to drive revenue and profits. The CIO has the talent and expertise in infrastructure development to create the company’s Big Data backbone and generate the necessary insights.

The relationship, however, has often been a fractious one. Marketing’s growing data demands of speed, availability, and agility in rapidly changing customer behaviors don’t align with IT’s modus operandi of developing and maintaining hard coded, legacy systems. The need for speed alone is a massive shift from “business as usual” for IT, which needs to develop new notions of data recency, availability and accessibility as they relate to helping the business improve its analytic decisions.

That impasse has led to expectations of the CMO’s IT budget outstripping the CIO’s by 2018, according to Gartner, a dangerous trend that can lead to duplicate spending and effort. Recent research also suggests that most CMOs today see marketing as the natural leader of big data efforts, while most CIOs see IT as the logical lead.

While the difficulties of the relationship between the CMO and CIO is a popular topic in trade journals and blogs, what’s needed is a more practical approach for addressing the issues.

One of the most important factors for success in Big Data and advanced analytics, for instance, is understanding what you want…precisely. When you’re looking for a needle in the haystack of big data, you really need to know what a needle looks like. A successful partnership, therefore, begins with the CMO being able to define business goals, use cases, and specific requirements of any data or analytics initiative. What the CIO needs to provide is feasibility and cost analytics around requirements based on use cases. That requires clearly articulating trade-offs and options in terms of cost, time, and priorities.

CMOs and CIOs can take other very practical steps to improve communication. At one company, the CMO and CIO have taken the step of having offices on the same floor. At Nationwide, a global insurance company, the CMO and CIO host a dinner for their leaders each quarter with the explicit goal of building camaraderie and trust within their teams.

Shared goals and proximity, however, cannot overcome the common the stumbling block: the lack of a shared vocabulary. “Marketers and technology people speak very different languages, so there’s a need on both sides to become bilingual,” says Becher. We have often seen two very intelligent people completely misunderstand each other. When it comes to defining use cases, for example, the CMO will often mean a few clear sentences. The CIO, on the other hand, is expecting 10 pages of single-lined details for each one. Frustration will quickly erupt unless both the CMO and CIO take the time to explicitly bridge the expectations gap.

In addition to clearly defined, goals, empathy, and a shared vocabulary there are five other imperatives necessary for CMOs and CIOs to make their partnership work:

1. Be clear on decision governance. An effective decision governance framework makes clear how the CIO and CMO, and other members of the leadership team, must work together and support each other. This is much more far-reaching than a data governance framework, as it covers every stage in the journey of translating data into value — from setting strategy, to the construction of use cases, to the deploying of budgets and capabilities. Teams need to be explicit about who will make what decisions, when. This can be a particular stretch for the CIO, as it gives a key business user — the CMO — a direct role in the design of data systems. Nationwide has developed a Business Transformation Council to explicitly tackle governance issues.

2. Build the right teams. The two executives must lead a common agenda for defining, building and acquiring the advanced analytics capabilities required to support the effort. In our experience, that often requires the creation of a Center of Excellence (COE) where both marketing and IT people work together. They must also agree where those critical capabilities will be located – in the COE or distributed across functions and locations — what the lines of reporting are, and whose budget will pay for them. To help make this decision, map out the stages of the “Big Data value chain” — from data architecting to delivering the message or product – and describe the necessary capabilities and responsibilities for each stage. Assign roles with the understanding that there may need to be multiple roles for a given stage and that each stage will often require someone from both IT and marketing. One important lesson that Nationwide has learned in bringing their marketing and IT organizations more closely together is that in analytically-oriented companies, skill sets become indistinguishable in business, marketing, and IT.

3. Bring complete transparency. The CMO and CIO (and potentially the CTO) must bring complete transparency to the process. Not only must they sit down at the start to define data use requirements with precision, but they must then meet regularly — bi-weekly or monthly — to review progress and keep the effort on track. Each quarter they need to sit down and have a frank discussion on the CMO-CIO “State of the Union” — and how to strengthen and sustain it as big data plays an ever greater role in business growth, and changes in technology create new opportunities to deliver more, faster. Develop a single scorecard that tracks progress and identifies breakdowns. Addressing these issues cannot be about assigning blame — that will quickly create a toxic work environment – but should be about having clear accountability and working collectively to fix the problems.

4. Hire marketing/IT “translators.” Goodwill, effort, and clarity will go a long way to bring the CIO and CMO together. But the reality is that few CMOs or CIOs have the right balance between business and tech. What each needs to do is hire “translators.” The CMO needs to hire someone who understands customers and business needs but “speaks geek.” The CIO needs to hire technical people with a strong grounding in marketing campaigns and the business. “Business solution architects,” for example, put all the discovered data together and organize it so that it’s ready to analyze. They structure the data to ensure it can be queried in meaningful ways and appropriate timeframes by all relevant users.

“At SAP, we have a Business Information Officer (BIO) for each business unit, including SAP Marketing,” says Becher. “The BIO must understand and translate business strategy into an IT enterprise architecture strategy and help guide technology investments.

5. Learn to drive before you fly. The CMO and CIO can’t hope to turn things around over night. In fact, that’s a recipe for disaster. Instead, they need to identify and focus on a few small pilot programs to test team compositions and new processes for collaboration. This approach allows teams to develop best practices and valuable lessons that can then be used to train other teams. Don’t be afraid to fail, but keep the projects and teams small enough at first to both fail and learn quickly.

Effective use of Big Data is already separating the winners from the losers across a wide range of industries. But there are no short cuts to getting it right―and the CMO and CIO share total responsibility for success or failure.

CEOs Should Imagine They’re at Davos Every Day

Trust in companies — which collapsed during the financial crisis — has improved in most countries, but according to our Edelman Trust Barometer, this recovery of confidence has stalled. CEOs are trusted by a mere 43% of the survey’s respondents; only government officials fared worse (36%). Real trust is put in people “like myself” (62%) and academics or experts (67%).

The fact that the trust gap between business and governments is widening (in favor of business) does not reflect corporate achievement, but governmental failure. Criticism of leaders in both realms has become a ritual when some of the world’s most elite gather for the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, which ended last week.

So why is the public so skeptical of companies and their bosses?

One core problem is that many chief executives rarely make themselves heard. They speak around the time of the earnings call, but then talk mainly about performance and numbers. Beyond that narrow window they keep quiet, worried about regulators and misleading earnings guidance. The irony is that — analysts and investors apart — most people couldn’t care less about quarterly performance. They want to hear about a company’s innovation and its response to broader societal issues.

Not only do many CEOs fail to address the right topics; they often fail to engage at all — whether with groups of employees, on social media, or in one-on-one meetings. Many chief executives even shy away from classic media interviews. Journalists often tell us that when CEOs speak to media, they typically sound “too messaged” and overly scripted. It’s like conducting an interview with a compliance department, not a person.

Part of the problem sits squarely with a certain school of PR professionals, who preach “message discipline” at all costs. Yes, CEOs need to be careful, but not to the point where they ignore the topics of greatest interest to the public.

And here’s another barrier: the chief executives themselves. They have many skills, but media and stakeholder relations are typically not a part of that. In contrast, the CEOs adroit in media and stakeholder engagement tend to make it a priority. One CEO of a multinational corporation told us that on his path to the top he deliberately sought the help of a media coach. And as we know from journalists and influencers, his investment paid off.

Another factor that makes chief executives sound stiff is the setting. Media engagement is built into tightly regimented days that are not conducive to relationship building. And here is where Davos re-enters the picture. The meeting is one of the only places where top global CEOs speak comfortably to other leaders and to the press. The WEF deliberately strips away much of the corporate shell of handlers and lawyers. More importantly, the purpose of Davos is not just to talk, but also to listen. Conversations there tend to be wide-ranging — not reduced to performance and earnings, but about context and insight. Davos turns many leaders into good talkers, making business leaders into a source of positive corporate stories that would be certain to raise trust in companies.

That’s because of the way they are told: by executives who appear sincere, engaging, and at times full of humor. These CEOs come across as humans, as people one can trust.

So to regain the public’s trust, chief executive officers need to learn a lesson from Davos and start communicating differently. Instead of reverting to type and staying on message, they should ask themselves: What if I were as straightforward with the public as with my peers? What would I do and say in Davos?

February 3, 2014

Jamie Dimon’s Pay Raise Sends Mixed Signals on Culture and Accountability

The JP Morgan Chase board of directors has vexed the world with its terse announcement in a recent 8-K filing that CEO Jamie Dimon would receive a big pay raise — $20 million in total pay for 2013, up from $11.5 million for 2012, a 74 percent increase.

Not surprisingly, the news sparked strong reactions, from indignant critique to justification and support. Dimon’s raise obviously has special resonance because JP Morgan’s legal woes were one of the top business stories last year as it agreed to $20 billion in payments to settle a variety of cases involving the bank’s conduct since 2005 when Dimon became JPM CEO. But the ultimate question that gets fuzzed-over in the filing and response is one of culture and accountability — whether a long-serving CEO is accountable for a corporate culture that has spawned major regulatory inquiries and settlements across a broad range of legal issues, even though the firm has otherwise performed well commercially.

If, as many would argue, a core CEO job is to create the company culture, the board of directors seems to ignore that bed-rock corporate principle when it increases Dimon’s pay, without much explanation, after several years in which the failings of the JPM culture were on the front pages for all to see.

According to news reports, there was disagreement within the JPM board about whether Dimon should receive a large increase or have his compensation basically stay flat at the 2012 amount which reflected a substantial decrease from 2011 (about 50 percent) as a result of losses and improprieties relating to the derivative trading of the “London Whale.” Similarly, commentators have been divided about whether the raise was deserved or not, citing both economic performance (2013 was about the same as 2012) and Dimon’s handling of diverse legal and regulatory issues for support.

The root problem is that the board failed to clearly articulate its reasoning for this important, high-profile decision on a fundamental matter of pay for performance. The announcement made the board seem oblivious to the fact that these issues have been center stage since the beginning of the financial crisis and, in fact, are of signal importance to the whole financial services industry and, indeed, to all major corporations. Instead, the regulatory filing simply listed, in summary fashion, “factors” supporting the raise, without any analysis elsewhere: JPM’s long-term performance; gains in market share and customer satisfaction; resolution of regulatory issues; improved control structures and processes; and leadership improvements. (The short phrase “regulatory issues” hardly captures the depth and breadth of major matters JPM agreed to settle in the past two years across a broad array of problems (summarized here).

A legitimate case can be made for Dimon’s 2013 raise. ($18.5 of the $20 million in total comp is in restricted stock units that vest in equal increments, in two and three years even if the stock is flat). The bank earned about $18 billion, down from $21 billion the year before. But, according to analysts, without legal costs attributable to 2013 and with other adjustments, the net would have been equal to or better than the prior year. The stock price rose more than 30 percent, in line with other major financials — and the company had high rankings in such areas as fees on debt, mergers & acquisitions, syndicated loans. Dimon dealt with regulatory issues head on. He criticized the bank and himself for the Whale. He acknowledged in his annual letter to shareholders in 2013 that “we are now making our control agenda priority #1,” and added 5,000 employees in control functions (for a total of 15,000). He also personally took over negotiation of major legal controversies and faced into payment of out-sized settlements to put the matters behind JPM. As well, the multiplicity of legal matters could plausibly be attributed to “piling on” by the government, not markedly poorer performance by JPM than other major financial institutions who also face a wide variety of regulatory problems.

In short, it can be argued that Dimon has positioned JPM for solid growth going forward, presumably with far fewer legal problems. By this argument, he deserved a raise that simply put him back close to where he was in 2011 before his compensation was cut for 2012 — a cut instituted because of, in the board’s words, his “ultimate responsibility” for the $6 billion dollar London Whale embarrassment.

The case against the raise begins and ends with JPM’s corporate culture, for which Dimon also bears ultimate responsibility. The broad array of issues for which JPM has paid settlements totaling billions all took place on Dimon’s watch. Except for the inherited Washington Mutual and Bear Stearns bad practices, they all involved JPM employees. They involved core bad behavior: collusion, inadequate disclosure, money laundering, abusive behavior towards debtors, indifference to red flags of massive fraud. They arose in different parts of the bank, not just one dysfunctional unit. They substantially impacted profitability. They have seriously corroded the bank’s reputation with regulators, a number of investors, and the public. JP Morgan’s own report on the matters surrounding the London Whale indicates broad failings. Dimon himself, after virtually all the problems had surfaced, admitted that under his leadership the bank had failed to pay enough attention to controllership issues, and had failed to create an appropriate culture of integrity, compliance and risk management.

To be clear, the argument against the raise is not an argument against retention of Jamie Dimon as head of JP Morgan Chase (or for his removal as chairman). Despite this core failing on corporate culture, he is obviously an extremely talented CEO in many other respects. But, the board should recognize the primacy of corporate culture and determine that, in a year when that culture’s weaknesses have been exposed in searing fashion, it is sending the wrong message to return Dimon’s comp to its former level. Economic performance in 2013 should not be the reason since it was roughly comparable to performance in 2012.

Because the words of the 8-K on the raise were so opaque, and because the question of CEO accountability for corporate culture is so critical to business, the JPM board of directors should have articulated its reasons more carefully and completely on an issue of such importance. If the board does indeed believe in the centrality of corporate culture and that the CEO is accountable for creating and sustaining that culture, then it should clearly make that case — perhaps in Proxy Statement comp section. It should clearly state that Dimon’s actions and words are making a difference — and why; and that a major reason for the raise is this process of candidly confronting issues and affirmatively changing resources, systems and processes — and ultimately the culture.

This may not persuade the most obdurate critics, but it would be the right argument for an increase in CEO compensation for JPM’s very troubled and troubling year. Instead, obviously feeling defensive, some members of the JP Morgan board, days after the announcement, spoke on background for a New York Times column that indirectly sought to explain their reasoning using some of the arguments above.

Without hearing more from the board itself, however, the critics of the raise, in my view, have the stronger argument. We should not have to speculate about the pros and cons of a decision with such high visibility and symbolic importance for the corporate and financial world. The board should step up and speak up to send a clear signal.

What We Know About Income Mobility Depends on How We Define It

The US has long had higher inequality than other advanced democracies, although many Americans see this as part and parcel of the “American Dream” of rising living standards and social mobility.

But recent research by Harvard University’s Equality of Opportunity Project has opened up a new front in this debate. The authors establish that social mobility between generations has in fact remained quite stable in America over recent decades, by calculating the likelihood of an individual’s rank in the economic pecking order corresponding to their parents’. This means that “children entering the labor market today have the same chances of moving up in the income distribution (relative to their parents) as children born in the 1970s.” For some commentators these findings refute the connection between inequality and mobility that President Obama and liberal economists have been invoking, and others even go so far as to claim it proves the uselessness of a variety of social interventions to promote mobility, such as college grants for minorities.

So what exactly does this study show, and how reliable is it? It depends on how you define “mobility.” If you think it is about relative positions in a stratified society, it has stayed roughly the same. But if you think it is about relative incomes, it has gotten worse. A married couple where each partner earned $60,000 a year would make it into the top quintile, not exactly the stuff of riches, given America’s high cost of living. But that is still considerably higher than the bottom of the spectrum, where the top of the lowest quintile caps out at a household income of about $27,000 a year.

And the Harvard researchers are quick to underline that although they find that mobility has remained stable, the rise in inequality over the last 40 years means that the consequences of immobility are far more serious than in the past. The 8-9% likelihood that a child born into the bottom twenty per cent will reach the top twenty per cent of earners has barely changed over the period studied (the research follows cohorts born between 1971-86). However, that low probability is clearly a more serious matter now because of the growing gap between the two groups: even if you exclude the very richest and the very poorest as outliers, this becomes clear. In 1980, the least-rich wealthy (the bottom of the top quintile) had three times as much wealth as the richest of the poor (the top of the bottom quintile); today, they have over four times as much. And the incomes of the top 1% have grown much, much faster – from 10 times as the earnings of the bottom 90% in 1980 to 33 times as much today (my own calculation, from the World Top Incomes Database). The average payoff of choosing the right parents has therefore increased.

Previous studies have found that inequality and mobility are negatively correlated, a finding aptly christened the Great Gatsby curve. This suggests that inequality may hurt mobility: in a very unequal society, the disadvantages of the poor and the advantages of the rich are compounded by the size of the gap between them. Wealthier children have access to better education, and even better nutrition and healthcare, setting them off on life’s path with advantages that secure an excellent prospect of matching their parents’ success. The poor not only have less chance of reaching college, they also face higher risks of incarceration, poor health, and drug abuse, all of which make it even less likely they will break out of poverty.

The Harvard study does however challenge some of the most pessimistic predictions about the consequences of higher inequality in America. It turns out that higher inequality does not automatically translate into lower mobility; after all, if the ‘Great Gatsby curve’ were a general law, then the United States, with its dramatic rise in inequality since the 1970s, would surely by the best laboratory to test that theory out. But does the Harvard team’s study suggest that the Great Gatsby curve is in fact spurious, and that inequality doesn’t affect mobility after all?

It’s not quite clear. The inequality-immobility relationship is certainly borne out by cross-national comparisons – more egalitarian societies have much higher mobility than the United States. But we don’t know whether changes in inequality over time within one country will affect levels of mobility, and if so, with what kind of time lag. We may simply be observing that on the whole, mobility is higher in countries with lower inequality because of a range of institutional and social conditions which may not change much over time, even when inequality does change. These ‘fixed effects’ may be driving much of the difference in mobility between countries, but do not produce much change within countries over time.

Another complication is that measuring social mobility across generations requires us to estimate a phenomenon that takes a long time to mature. To have a truly accurate measure, we would need to look at individuals’ incomes over a lifetime, but that poses insurmountable data limitations, as well as conceptual difficulties (is the mobility experienced by today’s seniors throughout their lives a measure of American society in the 1930s, or the 2010s?). The Harvard team takes cohorts born between 1971 and 1986 and measures their family incomes as children and adults, but even the oldest of these individuals are at most around halfway through their working lives, and youngest are barely out of college. They therefore make the reasonable assumptions, backed by existing data, that college graduation is a predictor of future income and that income at 30 is indicative of lifetime income. But still, this assumes that income dynamics over time will remain as they were in the recent past, which is far from certain. Even the youngest cohorts studied were born in an America rather more equal than it is today.

Even if these methodological doubts prove unfounded, there is a further reason to be resist dismissing the Great Gatsby curve out of hand. Much of the increase in inequality in recent years has been driven by the yawning chasm between the very top of the income distribution and everyone else. The Harvard study shows that it is the much slower growth in inequality amongst the bottom 99% which more likely explains why social mobility and overall inequality have not moved in tandem.

The Great Gatsby curve is therefore qualified but very much alive. To the extent that rising inequality is driven in some measure by the gains of the 1%, it should not surprise us that its effect on overall mobility should have been muted. But another possible conclusion is that rising inequality has cancelled out the effects of the many measures which have democratized American life since the postwar age, where incomes were less unequal, but gender and racial discrimination were rife. Greater access of women and minority groups to education and better-paying jobs have likely improved mobility, but at the same time the effects of growing poverty and the dismantling of labor protections and progressive taxes have pushed in the opposite direction. Social mobility remains caught between these two powerful forces.

The bottom line is: society is more unequal, but it’s not more mobile, so the fact that only 8-9% of the bottom fifth make it to the top fifth is now far more important than it was when inequality was lower. The stakes are getting higher, but your chances of winning haven’t budged.

Strategy in a World of Constant Change

Am I the only person to be getting a bit weary of hearing it repeatedly asserted that we’re living in a world of constant, accelerating change? That competitive advantages are becoming ever more transient and that the secret to survival will be to the ability to transform on a dime? Otherwise, what happened to Tom Tom will happen to you. Please!

Let me share a fun clip with you, sent to me the other day my former colleague Jonathan Rotenberg, founder of the Boston Computer Society. It chronicles Steve Jobs’ first public introduction of the brand new Macintosh, which happened in January 1984 at Jonathan’s Society in Boston. The whole event was was a cool trip down memory lane.

The moment I loved most was during the Q&A when an older gentleman asked Jobs a challenging question about the mouse as user interface technology: did it really compare favorably to the traditional keystroke approach? It was fun to watch a younger, mellower Jobs give a patient, reassuring response and not insinuate that the questioner was a moron. Jobs turned out to be quite right in his answer, which was that once people gave the mouse a try, they would see that it was far superior to keystrokes.

The really interesting thing about the gentleman’s question was the fact that it was asked 19 years after the mouse was shown to be a definitively superior graphical user interface at Xerox PARC in 1965. It didn’t become the default tool with the launch of the Macintosh in 1984, even though today the entire universe of computer users would be totally bereft if someone took away their mouse because it is acknowledged now to be so utterly superior to keystrokes. That didn’t happen until the release of Microsoft Windows 95, 30 years after it had given clear proof of superiority in 1965, as my friend and graphical user interface legend Bill Buxton likes to point out.

Science fiction guru William Gibson expresses this phenomenon very nicely: “The future is already here — it is just not very evenly distributed.”

His point, of course, is that when entirely new, transformative futures arrive (like the mouse in 1965) their effects take a long time to become evenly distributed — typically a long, long time even in the supposed fast-moving tech sector. Yes, Amazon is utterly transforming the way Americans shop, but 20 years after it was founded, it still has a fractional share of most goods other than books. Even in books, it took a decade for it to really hurt Barnes & Noble and Borders.

One lesson from this is that real competitive advantage is enormously long-lived. I remember helping Mike Porter with his terrific 1996 HBR article What Is Strategy? In it, he talked about the competitive advantage of Southwest Airlines, Vanguard Group and Progressive Insurance. Almost 20 years later, after huge changes in their industries, all three are still on top.

To be sure, first mover advantages can vaporize quickly, but not all first mover advantages are backed by a real competitive advantage. So if I hear the demise of MySpace cited once more as evidence that competitive advantage has become more transient, I will puke. All it proves is the basic rule of business: that which can be built simply and quickly can be simply and quickly torn down.

Another lesson to draw from Gibson is that certain futures can be seen very early if you look carefully at faint initial signals. It is possible to say that the dominance of the mouse was inevitable even as of 1965 because it was just plain better. Betting on the mouse over keystrokes was probably a safe wager even in 1965, though assuming widespread adoption in no time would have been a losing bet. Similarly, you could probably have concluded that wire line phones were headed for the trash bin as early as 1973 with the advent of Motorola’s Dyna-Tac mobile phone and that the creation of ARPANET in 1969 meant that print news was on its way out.

The danger, of course, is that in recognizing that a particular technology or industry is doomed you forget that they can take a long time to die. Going short on wire line carriers in the 1970s, 1980s or even 1990s would have been a bad idea and it’s only in the last ten years that the Internet has really started to kill newsprint and newspapers.

Strategy is a balancing act; it’s about judging between a fate being sealed and its being realized. Companies should not be in a hurry to abandon their competitive advantages in the wake of the hot new idea or technology. They must pay it attention because it may contain the seeds of their eventual destruction. But there is probably plenty of time to figure out what to. Thomson Reuters was both one of the world’s largest newspaper publishers and leading textbook providers as of 2000. It saw the signals and began a measured transition to becoming a provider of subscription-based, online must-have information, getting completely out of both the newspaper and textbook businesses while both were still highly profitable.

Advantage is neither transitory nor immortal. Hence, strategy is not an either-or exercise about seeking flexibility OR sustainability. It is about both: seeking sustainable competitive advantage in a world full of far-reaching and tumultuous change.

Start-ups: Before You Launch Your Product, Start With a Service

Raising funding for startups in Silicon Valley is a low probability game. Fewer than 1% who try actually succeed.

Outside the Valley, the startup eco-systems are mostly immature, and the probability gets even lower.

The bar to raise seed funding is getting higher and higher. Seed investors are mostly operating as growth investors, expecting that the entrepreneur will somehow manage to bridge the gap and bring a concept to realization. In fact, what these investors really want is to invest in businesses that have traction, not just validation.

In short, they want to come to the rescue of victory.

As an entrepreneur, how do you go from concept to traction? How do you bridge the seed capital gap? What do you do if you are full of dreams, but stuck in the gap between concept and seed?

Offering a service is one of the best ways to bootstrap.

This remains a controversial point of view. Most industry observers take the position that companies get distracted if they try to bootstrap a product with a service. But from where I sit, bootstrapping products with services is a tried and true method.

Let’s look at a few examples.

AgilOne, a company that provides cloud-based predictive customer analytics, was founded by Omer Artun in 2006. Initially, the company relied entirely on services to get close to customers, understand and address their problems, and in the process generate revenues. Today, AgilOne’s product is a software-as-a-service platform. Much of what the company learned about its customers in the services mode has been developed into its product, although a good percentage of revenues still comes from services.

Omer bootstrapped his company from no revenue or employees to about 45 employees and over $15 million in revenue by the time AgilOne partnered with Sequoia Capital in 2011. Silicon Valley’s top venture firm made a sizable investment at a high valuation in a company that was bootstrapped using services.

Andy Chou, a PhD student at Stanford, also bootstrapped his company, Coverity, using services. Andy’s research was financed by DARPA at the university. The technology allows automated cleaning up of large code-bases, and was licensed back to the company by Stanford.

Andy recounts his funding story: “We talked to all of the VCs and told them that if they wanted to invest in us, we would only consider certain types of deals. We presented them with our range of acceptable terms and indicated that if we did not receive offers in those ranges, we were content to continue bootstrapping the company as we had a solid clientele. We were in a sweet position where we had revenues and did not need to receive additional investments to succeed. As a result, we got a good deal from Benchmark Capital. They invested $22.3 million in us in 2007.”

In our incubation methodology at 1M/1M, we actively encourage entrepreneurs to engage in services businesses. In particular, we encourage them to immerse themselves with customers, learn their problems, and do some services projects that not only generate cash, but also generate customer intimacy and trust. Through these kinds of dialogues, entrepreneurs diagnose real pain-points in customers, and end up building products that customers are willing to pay for.

Consider one example from our portfolio: RailsFactory, a consulting and app development company that provides solutions for the web application framework Ruby on Rails, was co-founded by Senthil Nayagam and Dinesh Kumar in 2006. RailsFactory provides numerous services, primarily focusing on app development for the Ruby on Rails platform.

Senthil and Dinesh bootstrapped RailsFactory themselves, starting with about $1,250 in seed money. When they needed to, they each utilized other personal resources: Senthil reached into his savings, and Dinesh turned to his parents. But they started generating revenues fast—thanks to the services they offered, they were generating revenue by their second month, and they’ve been growing since. To date, RailsFactory has executed over 100 projects and has worked with clients in the US, Canada, India, Australia, Singapore, and the UK. Their services revenues have crossed a couple of million dollars, and the company has recently built a product that they have started validating with those 100 services customers. The productized offering enables them to offer a support package to the small- to medium-sized enterprise segment based on packs of trouble tickets.

Each of these companies bootstrapped to profitability via services. Not only is this a viable method of getting your startup off the ground, it’s a proven method of reaching profitability, as well. In some cases, it can take you to the enviable position of having VCs like Sequoia or Benchmark knock on your door. In other cases, you could even have investment bankers come calling, wanting to take you public, and a whole slew of late-stage investors wanting to shower you with funds. All those are desirable outcomes.

How Economics PhDs Took Over the Federal Reserve

There was a lot of uncertainty and debate last summer and fall over whether President Obama would appoint Janet Yellen or Larry Summers as Federal Reserve chair. What wasn’t really up in the air was whether the new head of the world’s most powerful central bank would have a doctorate in economics.

Yellen, whose first workday as chair (the Senate confirmed her as “chairman,” but the Fed seems committed to leaving the “man” out) is today, got her PhD at Yale. She also has more than two decades experience teaching economics, mostly at UC Berkeley, although for the past two decades she’s spent most of her time in various White House and Fed posts. Summers got his PhD at Harvard, and has been going back and forth between there and Washington, D.C., pretty much ever since. Obama also mentioned Donald Kohn (PhD, Michigan, and a career at the Fed) as a possibility, and the name of Roger Ferguson (PhD, Harvard, and a private sector career plus a past stint as Fed vice chairman) came up a few times in journalists’ speculations. The lone exception to the PhD rule was former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, possessor of a mere MA in international economics, but he took himself out of consideration early on.

In 2006, the last time a President had to nominate a Fed chairman, the job went to Ben Bernanke, who had spent his entire career as an economics professor before being called up to Washington for a stint as a Fed board member in 2002. The other main contenders seemed to be Harvard economics professor Martin Feldstein, Stanford economics professor John Taylor, and of course Columbia Business School dean (and economics professor) Glenn Hubbard, whose students made an awesome viral video about his purported disappointment at being passed over.

So has an economics PhD basically become a prerequisite for running the Fed? “I think the answer is ‘probably yes’ these days,” former Fed vice chairman Alan Blinder — a Princeton economics professor — emailed when I asked him. “Otherwise, the Fed’s staff will run technical rings around you.”

That Fed staff is loaded with economics PhDs. In fact, the Federal Reserve System is almost certainly the nation’s largest employer of PhD economists, with more than 200 at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington and what is likely a similar number (I got tired of counting) scattered among the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The first PhD economist to be Fed chairman was the illustrious Columbia professor Arthur Burns, who served from 1970 to 1978. History has not judged his tenure well. The next two chairmen didn’t have PhDs (although Paul Volcker had a master’s in economics). Alan Greenspan launched the all-PhD era in 1987, but his doctorate was of an unconventional sort — he acquired it in his early 50s from NYU after he’d left graduate school at Columbia decades before (Burns had been one of his professors) to start an economic consulting firm.

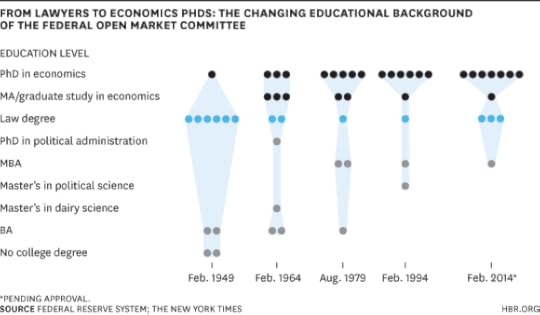

You can clearly see the PhDward shift in the makeup of the Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed’s main monetary-policy-making body:

I compiled this data in not very scientific fashion by picking a few FOMC meetings through the years, then getting the attendees’ educational backgrounds from the Richmond Fed’s helpful Federal Reserve history site, from the websites of other Federal Reserve Banks, and in a couple of cases from obituaries in The New York Times. The FOMC is made up of the seven members of the Federal Reserve Board, the president of the New York Fed, and a rotating crew of four other regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents — the total membership is usually less than 12 because of vacancies on the Fed board. The 2014 numbers above include two new Fed board members (Stan Fischer and Lael Brainard) and one renominated to a second term (Jerome Powell) who haven’t been confirmed by the Senate yet.

One obvious and unsurprising trend in the chart is that overall educational standards have risen. It doesn’t really happen anymore that a guy who drops out of high school to work at John Deere, as Robert R. Gilbert did, can end up as president of the Dallas Fed (although who knows, maybe Tumblr founder David Karp has a shot).

The other big shift is the one from lawyers to economists that happened after 1949. A little Federal Reserve history helps explain it: In reaction to the Fed’s muddling in the early years of the Great Depression, Congress reorganized it in 1933, creating the FOMC and giving the chairman in Washington more power. But the first chairman under this new structure, Utah banker Marriner Eccles (who as best I can tell attended but did not graduate from BYU), was an advocate of aggressive fiscal stimulus who didn’t believe that monetary policy mattered. So the Eccles Fed didn’t do much to stimulate the economy in the 1930s. Then, during World War II, Eccles acceded as the Treasury Department forced the Fed to buy U.S. government securities to keep interest rates down — in the process generating lots of monetary stimulus — and kept dictating monetary policy after the war. In 1949, President Harry Truman appointed Scott Paper CEO Thomas McCabe (BA in economics, Swarthmore) to take over from Eccles, and McCabe began pushing Treasury to give control over interest rates back to the Fed. The result was the Fed-Treasury Accord of 1951, which McCabe hammered out with Assistant Treasury Secretary William McChesney Martin. Then McCabe went back to Scott Paper and Martin took over as chairman of a re-empowered Federal Reserve.

Martin was a former stockbroker and New York Stock Exchange president who took graduate classes in finance at Columbia while working on Wall Street in the 1930s. He stayed on as Fed chairman until 1970 — the longest-serving ever, beating out Greenspan by a few months — and appears to have been largely responsible for creating the modern, economist-dominated Fed. Under Martin, regulating the economy through monetary policy pushed aside bank regulation to become the central bank’s No. 1 job. So hiring economists, and bringing people with serious economics backgrounds onto the FOMC, became a priority. There weren’t all that many people with economics PhDs around in the 1950s and early 1960s, so the Fed was willing to make do with less. Then the U.S. witnessed a PhD explosion, with the number of doctorates granted in all fields rising from 8,773 in 1958 to 31,867 in 1971 (currently it’s around 50,000 a year, of which about 1,100 are in economics). More and more of these PhDs found their way to the Fed.

Still, when Blinder arrived as vice chairman in 1994, he says the presence of an economics professor on the board still seemed new and different. The Fed staff was full of career employees with economics PhDs; some of the regional Federal Reserve Banks had begun appointing staff economists as presidents. But a career professor? ”I believe I was the fourth or fifth Board member to come from academia in the Fed’s entire 80-year history to that date,” he said. “Janet Yellen followed quickly, and the floodgates opened. Now it’s normal, even expected.”

The new Fed Board of Governors (assuming the Senate confirms the latest nominees) will include veteran economics professors Yellen, Stanley Fischer, and Jeremy Stein, plus Lael Brainard, an economics PhD who has spent most of her career in Washington but did teach at MIT for a few years early in her career. The other three members are lawyers who have spent much or most of their careers in government. As for the Federal Reserve Bank presidents, eight of the 12 have economics PhDs and seven of those have spent much or all of their careers at the Fed. Two of the non-PhDs have spent their careers at the banks they lead, while only two bank presidents — Atlanta’s Dennis Lockhart and Richard Fisher of the Dallas Fed — fit the pre-1950 Fed mold of successful bankers/businessmen doing a stint as central bankers.

What are we to make of this economist dominance? The Fed makes economic policy, so it stands to reason that there should be economists involved. But graduate education in economics, especially in macroeconomics, comes under pretty regular criticism for being narrow and unrealistic. Could there be value in diversity of opinion and background as well as opposed to just economic expertise?

I tried a version of this question on my friend Roger Lowenstein, who is working on a history of the origins of the Federal Reserve, and has had withering things to say about certain economists in some of his previous books. He answered by splitting the Bernanke tenure into before the financial crisis and after.

During the “before,” he clearly suffered for not having any experience as a banker. Bernanke had never issued loans, had never evaluated balance sheets, and probably did not believe it was a macro useful thing to do. He, like Greenspan, believed that the market set a rational price on mortgage securities, so why waste a lot of time parsing balance sheets? Mistake.

After, on the other hand, “Bernanke’s experience as a monetary economist clearly has been enormously useful and beneficial. I doubt that a practiced loan officer could have done better.”

A Fed with lots of PhD economists is probably a good thing. A Fed with only PhD economists in its top jobs would be limiting itself. Diversity brings all sorts of positive side-effects; monocultures are fragile and unhealthy. The FOMC hasn’t gotten nearly as narrow in its recruiting as the Supreme Court, where the nine justices are the product of just three law schools (Harvard, Yale, and Columbia), and eight were U.S. appeals court justices before joining the Supremes. Let’s hope it never does.

Business Has Changed, and Even Washington Has Noticed

In the week’s worth of punditry following this year’s State of the Union address, one fact seems to have eluded most commentators: the number of times that President Obama recognized businesses as essential partners in national problem-solving. It marked a real contrast to the President’s prior SOTUs, and a new articulation of the role of business in society.

President Obama remarked on the “partnership with schools, businesses, and local leaders [that] has helped bring down childhood obesity rates for the first time in thirty years,” thereby improving lives and reducing health care costs; referred to commitments by 150 universities, businesses, and nonprofits “to reduce inequality in access to higher education—and help every hardworking kid go to college and succeed when they get to campus;” and asked business CEOs “to give more long-term unemployed workers a fair shot at that new job and new chance to support their families.” The President also announced that, with the support of the FCC and businesses “like Apple, Microsoft, Sprint, and Verizon, we’ve got a down payment to start connecting more than 15,000 schools and twenty million students over the next two years” to high-speed broadband.

This focus by the President on the vital role of businesses in addressing unemployment, education, and healthcare reflects an emerging new reality: corporations have become major players in helping to fix the world’s biggest problems. No longer are leading companies merely helping communities “on the side” as something “nice to do,” while trying not to deflect too many resources away from their “true” business mission. Today, some companies are discovering how dependent their fortunes are on a healthy world, and working to reduce expenses, mitigate risks, and increase profits by focusing their core business capabilities on solving environmental and social problems.

I would go even further to contend that multinational corporations—more than governments, and more than NGOs and nonprofits—have the human and financial capital, technology, international footprint, power of markets, and financial motivation to solve the world’s most daunting problems. (It’s why I chose the subtitle of my new book: A Better World, Inc.: How Companies Profit by Solving Global Problems…Where Governments Cannot.)

The Dow Chemical Company, for example, needs to assess costs and risks every time it considers a site for a new manufacturing facility. So it dedicated a team of its own scientists, engineers, and economists to develop, in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, a method of calculating the value produced for societies by surrounding ecosystems and how it would be affected. The assessment tool they are creating will provide data that Dow and other companies will use as input to their decision-making, allowing them to mitigate risk and preserve resources required by future generations (including the future of their business). Johnson Controls has 170,000 employees and specializes in optimizing the energy and operational efficiency of buildings. Who better to retrofit an old building like the Empire State Building in New York City or the Inorbit Mall in Mumbai, simultaneously cutting carbon footprints and improving profits? Just last night, during the Superbowl, Microsoft advertised its new technology to enable the hearing-impaired to hear; out of all the profitable products it could have allocated R&D resources to, it chose to invest in a socially important one.

It is not only their technical skill but also their titanic scale that put companies in a position to solve national and global challenges. The nonprofit sector has made strides in advancing the human condition but individual organizations often lack the resources and scalability to make transformational progress. National governments acting alone lack the footprint and authority on the ground to deploy adequate resources in many territories. The international community often fails to achieve binding and actionable agreements to overcome major challenges. Businesses can play a pivotal role in making more of these efforts successful by partnering with nonprofits and governments.

Even the companies whose leaders were not quick to take on the world’s problems are being drawn toward them. Increasingly, consumers, employees, and investors are demonstrating greater support for companies that advance solutions to social, economic, and environmental challenges. Conversations and exposure via social media hold companies accountable for their impacts.

We’ve reached an interesting point when a president called the most anti-business in our lifetimes uses a major speech to shine a light on the value and opportunities of business working alongside nonprofits and government. It’s time for us all to acknowledge that the state of our union, and the state of our planet, is better when companies put society’s biggest problems in their sights.

Women on Boards: Another Year, Another Disappointment

“Still No Progress After Years of No Progress,” reads Catalyst’s recently released 2013 census of women directors and executive officers in the Fortune 500. Indeed, the news is not good: the percentage of women directors in the Fortune 500 at 16.9% has remained flat (it was 16.6% in 2012 and 16.1% in 2011). Why, when there’s so much conversation about the topic, are the numbers not moving?

We contend in order to see real movement change must occur within three spheres: at the country, organizational and individual levels.

A number of countries have tried to devise remedies—from the legislative implementation of quotas to regulatory agency reporting requirements (e.g., of the gender composition on boards)—to increase women’s representation on boards. And we have also seen a vast amount of enterprise and energy brought to bear at the individual level through education and networking organizations, many of which are designed for and focus solely on women. But we haven’t seen as much effort at the organizational level, which we believe could be the most determinative lever of change. In fact, we are not aware of a country that has seen effective action in all three. A case in point is New Zealand.

New Zealand’s Challenge

The country has been cited as a standout on the gender-gap front, consistently recognized by the World Economic Forum (WEF) as a leader based on evaluation of four domains: economic participation and opportunity, political empowerment, educational attainment, and health and survival. Additionally, the New Zealand government has endeavored for many years to provide support to working women and families, for example, passing the Parental Leave and Employment Protection Act in 1987 which mandates paid maternity leave and subsidized daycare for working mothers. In the corporate sphere, the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) implemented the Diversity Listing Rule in 2012 that requires companies to annually report their boards’ gender composition.

Yet, the percentage of women on boards in New Zealand remains in the single digits. Recent estimates put the percentage at 7.5% for female directors and just 5% for women in leadership positions such as Chairperson. In 2012, we surveyed (in partnership with WomenCorporateDirectors and Heidrick and Struggles) more than 1,000 board members in 59 countries including New Zealand. To increase the sample size for a country-focused analysis of New Zealand, we administered the survey to a second wave of New Zealand directors between December 2012 and March 2013.

Subsequently, we examined the challenges that the New Zealand boards have been facing. Our findings point to certain factors that may be contributing to this lack of progress. These analyses, however, should be interpreted with care. Our sample included low numbers of women directors—mirroring the low overall numbers of women on boards in New Zealand. Therefore, the analyses are suggestive, but we hope they will encourage more research and collection of broader data. Our findings:

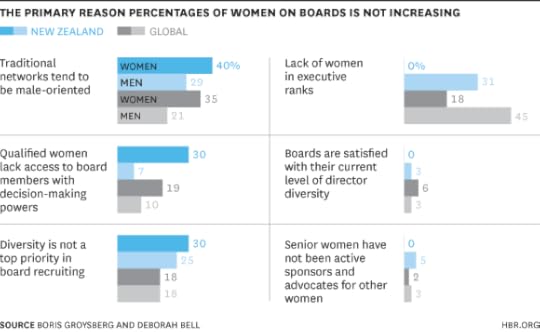

Different Diagnoses: We discovered an important difference between women and men directors in New Zealand: the diagnosis of the problem. Women said it is because of lack of access to networks and those with decision-making power on boards, while men most frequently said it was due to lack of women in executive ranks—that is, a lack of qualified women.

These differences between male and female respondents were stark: 30% of women directors in New Zealand said lack of access to those with board-level decision-making power was the primary reason the percentage of women on boards is not increasing; just 7% of the men directors agreed. And 40% of New Zealand women directors versus 29% of men cited closed male-oriented networks as the chief problem. Conversely, 31% of men directors said lack of women in executive ranks was the chief reason for the stalled progress; not one woman director named this as a reason.

We also found that a greater percentage of both women and men directors in New Zealand versus global women and men directors said that diversity was not a top priority when recruiting for their boards and the primary reason for the stalled progress–a finding that suggests the disconnect between the organizational and country level processes at work to increase the number of women on boards in New Zealand.

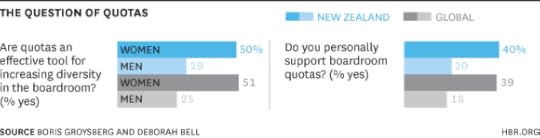

Different Views of Quotas: Women directors in New Zealand, like their female counterparts elsewhere, show far greater support than men for quotas both personally and as effective tools for increasing the number of women on boards. This gender divide is another indicator of the vastly different orientation to the problem and its possible solutions. Not only are female directors more likely to say there are enough qualified women but they’re more likely to think the chief problem sits within the boardroom.

A finding from our 2012 survey offers an intriguing variation on this theme. We discovered that “men in countries with quotas supported them in higher numbers than men in countries without them.” While more research is needed to achieve a deeper understanding of this finding, it might suggest that once male directors experience gender diversity on boards, they might appreciate the different perspectives more than they’d anticipated.

Different Profiles: A substantially smaller percentage of women board directors in New Zealand (56%) than men (84%) were married, fewer had children (72% of women vs. 90% of men) and those that did had fewer children than men (average number of 2.4 children for women vs. 2.7 for men). And strikingly, almost twice as many women than men had advanced degrees (88% vs. 45%, respectively). These differences raise the question: might there be a greater cost paid and higher qualifications needed by women to reach the same level of career achievement as their male colleagues?

We found that New Zealand’s women and men directors had served on average on the same number of boards during their careers but women were currently serving on more boards—by almost one full board. And although men and women directors in New Zealand were serving on the same number of boards in their career, men were sitting on boards longer than women. Last, we found that even though the New Zealand women directors were currently sitting on more boards than men, far fewer held leadership positions on boards.

These findings raise several questions: Although women directors in New Zealand are more highly credentialed and serve on more boards, why do they hold substantially fewer leadership positions on boards? How do we make sense of these results in the context of New Zealand’s ranking as one of the top countries for gender equality in the world? More research is needed to explore these questions.

Simultaneous Action

It may be too soon to tell how effective the NZX’s Diversity Listing Rule will be at increasing the percentage of women on New Zealand’s listed company boards but all boards will benefit from a deliberate and thoughtful implementation of more rigorous, objective, and transparent selection processes for directors. We studied one such process in a large company in New Zealand that was being divided. To create the two new boards, the chairman named a special team to determine and run the selection process. The team began by identifying the skill sets each board would need and then created a model that detailed the expertise and behavioral attributes necessary for each board to execute effectively. Their approach remained rigorous and transparent throughout and in the end both companies appointed boards that were diverse both in skills, attributes and gender.

There is a need for simultaneous intervention at a country, organization, and individual level in order to make progress in the representation of women on boards. As evident from the data collected from New Zealand, as well as examples from many countries around the world, tackling only one or two levels will not be enough to produce results.

In New Zealand, the government is taking a more proactive role in promoting female board representation, and clearly there is enough qualified female talent in the country (some might argue even more qualified than their male counterparts). What is missing is intervention at the organization level. Our research revealed several opportunities for improvement within New Zealand’s boards, including identifying and appointing directors with the skills their boards need, effectively onboarding and training new directors, managing their own dynamics, and succession planning practices that include building more diverse governing bodies.

To move towards greater parity, it might be time for boards around the globe to take purposeful action: to open up and expand their selection processes, to recruit and appoint directors with greater diversity of skills, attributes, and gender, and strengthen their overall governance practices. Lest without such intervention at the organization level, we will continue to say “Another year, another disappointment.”

Methodology

We surveyed more than 1,000 board members in 59 countries. Groysberg and Bell administered the survey to a second wave of New Zealand directors between December 2012 and March 2013. We analyzed the data along several dimensions including geography and specifically for this analysis we did a New Zealand and Global breakout. The average amount of time respondents reported that it took them to achieve their first board service, may have been affected by the involvement of an executive search firm.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers