Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1479

January 27, 2014

Don’t Write Off the (Western) Focused Firm Yet

The rise of Tata in India, Koç Holding in Turkey, and Grupo Carso in Mexico have some management thinkers contending that the conglomerate is back at the expense of the focused firm. In his article “Why Conglomerates Thrive (Outside the U.S.)” in the December 2013 issue of the Harvard Business Review, J. Ramachandran concludes from a study of the performance of listed Indian business groups that the conglomerate is a winning organizational structure, even if isn’t popular in North America yet. In its January 11th issue, The Economist also argues that conglomerates are spreading their wings again. Often the debate turns ideological, arguing that the (emerging-world) conglomerate is an intrinsically better construct than the (Western) focused firm.

In our opinion, which of the two is the more successful depends on the context in which the business operates. Specifically, focused firms fare better in countries where society expects and gets public accountability of both firms and governments, while conglomerates succeed in nations with high public accountability deficits.

Simple micro-economics sheds light on the issue. Imagine you are starting a new business. What will make it successful is your ability to induce customers to buy from you rather than from someone else. As long as the revenues you obtain from those customers exceed your costs, you will turn a profit. You would consider first whether you could offer a distinct product to each individual customer that perfectly matches his or her unique preferences. Of course more often than not you would find out that such extreme customization is not profitable. As a consequence, you would begin to lump similar customers together into segments to which you offer a “compromise” product. While you no longer extract maximum value from each customer, you are still better off as a result of economies of scale and scope.

As this phenomenon repeats itself, the diversified firm is born. You add product families first, followed by business lines, each time addressing extra customer segments. As long as the extra revenues justify extra costs, and economies of scale and scope outweigh the cost of increased complexity, it makes sense to continue diversifying.

The nature of these economies of scale and scope change as you diversify more and more. Initially these savings are mainly physical, as you stretch the use of tangible assets such as plants, networks and systems. Subsequently they become more knowledge-based, as you share technologies, brands and customer intelligence. Finally, when you are at the conglomerate stage, they relate to social capital, as you move talent across internal boundaries and leverage personal relations with politicians, government officials, investors and other external parties who can greatly facilitate or obstruct your plans–not necessarily with the greater good in mind.

Given the still-prevailing “conglomerate discount” Western firms are subject to (i.e., the conglomerate share price is less than the sum of the values of its constituent businesses), we would argue that the economies from leveraging personal relations with external parties are non-existent in these firms. The forces of lawmaking, jurisprudence and, yes, ethics bring about sufficient transparency, market efficiency and fair business behavior for the conglomerate not to be worth its salt.

In the emerging world, however, these forces may be underdeveloped. In such cases officials, investors and other parties put extraordinary trust in the people they know at the helm of the successful conglomerate, for example to realize their pet projects, invest their funds or set up a joint venture – and are willing to pay a premium for it. For example, the local connectedness of emerging market conglomerates is one of the main reasons why many Western firms, in industries as diverse as electrical power and insurance, set up joint ventures with them. In addition to serving customers – which stays the very raison d’être of a firm – the conglomerate thus serves also as a conduit for initiatives that the external parties otherwise might find too risky to pursue. For example, investing in a partially listed subsidiary of a conglomerate that has been around for more than 100 years in a volatile emerging market gives a greater sense of comfort than going it alone.

Take a tobacco company in the U.S. It may spend fortunes on lobbying, but it is all about promoting its one business activity, i.e. tobacco. It doesn’t get into, say, cereals, because it realizes that knowing this one Congressman won’t make it as successful in cereals as a focused cereals manufacturer. There is no “scope effect.” But if this tobacco company wants to enter, say, India, it could establish a joint venture with a local conglomerate that has all the right connections, be it with a governor for land, another firm for electrical power, etc. It doesn’t matter that this conglomerate isn’t in tobacco yet. It just leverages its connections, and will somehow ask a premium for that know-who from its U.S. JV partner, for example by getting a higher stake in the JV than it otherwise would deserve.

We don’t expect this phenomenon to re-emerge in the Western world, and thus the conglomerate to regain a foothold. Quite to the contrary.

Consider PPG Industries. The US-based company used to be a diversified industrial group, with activities in all types of glass, chemicals, paints, optical materials and biomedical systems. Through a raft of acquisitions and divestments since the early 1990s, it has transformed into a focused world-leading coatings manufacturer with $15 billion sales. In 1995, glass and coatings each accounted for about 40% of sales. By 2012 as the firm became more focused, this split had evolved to 85% coatings and 7% glass. In that same period PPG’s share price has risen by a compound average rate of 6.6%, compared to 5.1% for the S&P 500 Industrials. Quite a respectable performance for a company operating in a fairly mature industry. It may well reflect the power of focus.

At the same time, we’re not arguing that conglomerates aren’t effective in emerging markets. One statistic that, unfortunately, may point to the lasting importance of local connectedness is the Corruption Perceptions Index published annually by Transparency International. It uses a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 10 (very clean). Since 1995 the index has remained stable at around level 3 in India and level 7.5 in the U.S., to take these two countries as an example. Until such public accountability deficits can be addressed, the economies of scope related to social capital (“this-person-I-know-and-trust-in-an-otherwise-untrustworthy-environment”) will sustain the conglomerate phenomenon in the emerging world.

The conglomerate is a “necessary evil” in many emerging markets: without it, things might not work. But it is a symptom of a deficit that has a high societal cost. That’s something to think through before heralding its return. In the meantime, (Western) consumers, investors, and society at large should be delighted with the focused firm.

Inequality in the United States and China

Income inequalities in the United States and China are not only high, and similarly high (which has been the case for a decade already), they are also becoming a serious political problem in both countries. President Obama in his 2012 State of the Union address called inequality a “defining issue of our time.” It subverts democracy and imperils equality of opportunity, arguably the two pillars on which the American Dream has been built. In nominally socialist China, the newly selected President Xi in his last year’s address to National Congress promised that tackling inequality will be his administration’s “top priority.” In China, high inequality threatens to undermine the Communist Party’s key justification to unchecked claim to power.

The turning point for both countries, launching them into ever rising inequality, took place at almost the same time: late 1970s and early 1980s. With the election of Ronald Reagan to the U.S. presidency and the policies of high real interest rates and lower taxes on “unearned” (capital) income, income inequality in the United States jumped and then kept on rising throughout the 1980s and the 1990s, before eventually plateauing at a very high level in the naughts. The overall outcome was that, measured by the Gini coefficient, U.S. inequality went from around 35 to 45 Gini points—that is, from a mid-range OECD inequality level to an OECD outlier surpassed only by Mexico and Turkey.

China, under Deng Xiaoping, introduced private ownership of land in 1978, and thus began its 35-year period of unprecedentedly high economic growth and rising inequality. During that same period, Chinese inequality increased at a tempo outpacing even that of the United States: inequality in China rose from a level lower than in the United States to a level equal or slightly exceeding that in the United States today.

In the Unites States, the growth of inequality is, in terms of explanatory factors used by economists, over-determined. There are many factors that have been adduced, and in some cases empirically shown, to have contributed to greater inequality. But they can be usefully divided into three groups: technological progress, globalization, and economic policy. Technological progress by favoring highly skilled labor to the detriment of the low-skilled, might have led to the increase in the wage premium (for the highly educated) and to widening inequalities. Globalization might have, by providing cheaper imports from China and allowing U.S. companies to hire cheaper labor abroad, led to a decrease in low-skilled wages, and likewise increased the gaps between the high- and low-skilled workers. In addition, globalization, by letting capital move much more freely than before, allowed entrepreneurs to find more profitable uses for their capital and to keep profit rate up, shifting the distribution in favor of capital and the well-to-do. Finally, economic policy, by reducing taxes on the rich has exacerbated these disequalizing trends.

What is the likely evolution of these three forces in the medium-term? The form that technological progress will take is, by definition, impossible to predict, but nothing seems to suggest that we are likely to enter an era of pro-unskilled labor innovations. Some innovations may be of this kind, as for example the use of cell phones to allow small farmers in Africa to get much more accurate and up-to-date information about prices, thus increasing their incomes. But nothing suggests that similar innovations are around the corner to help U.S. workers without a college degree. Globalization, as far as we can see, is also here and likely to stay. There may be minimal retrenchments, but the forces it has unleashed are too powerful, and the people who benefit from it are too numerous (particularly in Asia) that, short of a major war on the scale of the World Wars, it is unlikely to be put back in the box.

Which leaves us with economic policy. But there the news is rather bleak. Three decades of ideologically driven pro-market change, combined with an ever-greater ability of the rich to influence the political process, has created a stranglehold for the top 1% on the political agenda. Having invested several decades worth of effort and money into think tanks and lobbying to argue for low taxes on income and wealth, it’s unlikely that the rich will suddenly change their mind. Although the economic policies that could reduce inequalities are well known—higher minimum wage, cheaper public education, and above all higher taxes—the probability that they will be implemented is rather small.

The medium term in the United States will thus continue to look more or less like the present. But farther afield, the very foundations of democracy may be shaken by the plutocratic turn in governance and by the continued hollowing out of the middle class. Inequality may not change US way of life too much right now, but it might render its democracy vacuous, and sow deep the seeds of discontent with its political system.

The causes of inequality in China are different. There, the increase in inequality is primarily due to a transition of labor from low-productivity agriculture to a higher productivity industry, not dissimilar from the evolution in the United Kingdom between the mid-1800s and early 20th century or for that matter in the United States between the late 1800s and 1927. China, like the United Kingdom and the United States, is following an intense inequality upswing of the Kuznets curve (named after Russian-American statistician and economist Simon Kuznets), characteristic for all, or most, fast industrializers. But after a certain points, or so Kuznets’s theory suggests, equalizing elements kick in: urban-rural gap declines as agriculture becomes more productive, more people get educated (and the skill premium declines), and greater wealth as well as the aging of the population lead to increased demand for social welfare and thus redistribution. This is basically the path that the US and the UK both took after they passed the (previous) peak of their inequality some 100 years ago. On that reading of Chinese inequality, one can be optimistic: there are strong forces that may curb it in the future. We already see some first signs of it: from rising wages to the demand to extend the social safety net beyond urban state-sector workers.

But there are reasons not to be so sanguine. Chinese inequality is truly spectacular in the sense that it has exacerbated all cleavages: the urban-rural gap in China is greater than in any country in the world; the gap between the rich maritime provinces and the poor Western regions is growing; the gap between capital-owners (in a nominally socialist state!) and farmers is enormous. Reversing inequality means reducing some of these gaps, and this is a very arduous task: who is going to stop a Shanghai-based highly educated technician from earning more or compel him to share it with a Hunan farmer? How will far-away poor provinces become more developed? Will rich provinces be willing to fund the needed transfers?

More importantly, the single-party political system has led to massive corruption at all levels of government, but particularly at the top. The recent scandal that revealed secret bank accounts in the Caribbean belonging to the families of the top politicians underlines the massive extent of corruption throughout the system. As with the top 1% in the United States, it is hard to see that those in China who have profited the most from inequality will vote for lower benefits, lower premiums, and fewer opportunities for corruption for themselves

Thus, politics in both China and the United States seems to work against any realistic solution to stop or curb the rise in inequality.

The Chinese situation is more serious, however. Dissatisfaction with inequality can easily spill into the demands for political liberalization. That democratic alternative is especially attractive because the corruption of the rulers coexists with a justification for their rule – Communism – that is obsolete and that the elite themselves clearly ignore. The woes of the Chinese politicians are compounded because the gap between the official ideology and reality is huge and a political alternative to address this gap exists. In the United States, the gap between ideology and reality is smaller, and a political alternative is less clear, or at least commands less support among the population.

The solution to high inequality in both countries lies in the political sphere, but the chances for a short-term fix are low. Over the longer-term, change may hinge on democratic revolt in China and democratic renaissance in the United States.

Why I Hired an Executive with a Mental Illness

A few years ago, I was interviewing a candidate for a substantial position in our firm. Although the candidate and I had exchanged a number of emails, this was our first meeting. We got along very well. Then something unexpected happened: She looked me in the eye and said that she struggled with “mental illness.” She added that she’d been on meds for more than a decade, and that there had been no episode during that time. But she wanted me to hear about her condition directly from her, in case I had any questions.

We talked about her mental health, but only for a few minutes. I had never been in this situation before, and I honestly wasn’t sure what to say. I thanked her for her integrity, and we moved on.

My reaction to the candidate’s disclosure was, frankly, disbelief — disbelief that she found the courage to make herself so vulnerable before she was hired. She had to be interviewed by other members of the firm before I could invite her to join us, but we did hire her — and over the past few years, she has become not only a core member of our team, but a large part of the glue that holds the firm together.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 prevents employers from discriminating against people who have a mental illness. But my experience as a consultant at a very large strategy firm whose clients are giant corporations had been that if someone admitted that he or she struggled with depression or mental illness, that would often be career suicide. Indeed, a former vice president of a major investment banking firm, when told about this blog, warned me against publishing it: “Clients are afraid to work with firms that have mentally ill people on the professional staff.”

True, times are changing. We now read books and newspaper articles written by people who are brave enough to share with others their pain and their resilience — but, typically, these memoirs are not written by individuals who work in business. And while there are stories about executives in the C-suite who suffer from depression, these stories are rare.

I myself seldom heard people talk of openly of depression in the workplace until left the consulting firm where I’d worked to begin advising owners of leading family businesses. Much to my surprise, I found that these extremely successful family business owners don’t draw a sharp (and artificial) line between “us” and “them” – the mentally healthy and those less healthy. They don’t because they know they can’t. Those who suffer from mental illness are not anonymous shareholders, or nameless employees, but rather brothers, mothers, cousins, grandfathers, sons, and daughters. In family businesses, “they” are “us.”

This universality of mental illness is not something that is peculiar to family businesses. It is an integral part of the human condition, and reliable epidemiological studies confirm that there are no families that are completely immune to mental illness. Family businesses can’t escape these difficult emotional realities because they can’t just fire the guy suffering from depression when he is the majority owner. The successful families do find ways to work together. But even then, things are messy in family businesses, and it is out of this very messiness that the human side of capitalism emerges.

Businesses don’t have a great track record with the mentally ill. Today, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, some 60% to 80% of people with mental illness are unemployed. In part, this is the crippling nature of the disease. But a large part of the problem that we have in hiring people who have some mental disorder is that we lack the sophisticated vocabulary to talk and act regarding these illnesses. How often have you heard it said that somebody “had a nervous breakdown”— that vague 1950s euphemism — and had no way to know exactly what this meant?

With problems of the body, we have plenty of words to differentiate among, say, the common cold, the flu, and pneumonia. Managers are comfortable with physical illnesses. We can plan for how long the employee will either be out of work or unable to work at full tilt. By contrast, mental illness is thought of as “all or nothing.” You’re either depressed, or you’re not; mentally ill, or not. Yet the reality is that the mental illnesses, too, are nuanced. We all have more or less mental health at different times in our lives. But the lack of a working language, together with the terrible secrecy that festers around mental illness, makes understanding one another, and collaborating effectively, extremely difficult.

That’s a real pity, because sometimes it’s the person with the mental illness who can provide the cohesion, the humanity, or the breakthrough idea that separates your organization from all the rest. I am not a person who romanticizes mental illness. I do not believe that people on the edge of mania, for example, are more productively creative, insightful, or more brilliant. But I do believe that talented people who suffer from mental illness can add to the mix some different, and important, perspectives. It’s this diversity that is so crucial to good decision-making, and which gives an organization the competitive edge.

In the case of my colleague (who gave her blessing to this piece), what she brought to the table was deep self-awareness, a keen mind, and profound emotional intelligence. Working closely with her opened my eyes to finding talent – and a different kind of talent – where I had never seen it before. And when I am talking to candidates nowadays, in the final interview round, I ask them to tell me something deeply meaningful to them personally. Not everybody needs — or cares — to be so open as my colleague was, but if candidates can’t share some vulnerability, they’re out. They may be good, but they’re not good enough to work in any business which demands that we be fully human.

Residents of Poor Countries Have a Great Advantage: Religion

An analysis of polling data from 132 nations shows that religious belief appears to be the main reason why people in poor countries see greater meaning in life than residents of wealthy countries, say Shigehiro Oishi of the University of Virginia and Ed Diener of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Among the nations with the highest sense that life has meaning are Niger, Sierra Leone, Togo, Ethiopia, Laos, and Ecuador. By connecting daily experiences with a coherent belief system, religion plays a critical role in helping people construct meaning out of extreme hardship, the authors say.

The Four Secrets to Employee Engagement

How did you feel about coming to work this morning?

I’m sure many factors influenced whether you felt like digging right in, but one of the most significant was almost surely your boss.

It seems obvious: Direct supervisors who set their teams up for success, observe them in action, ask for feedback, identify the root causes of employee concerns, and then follow through with meaningful improvements have happier, more engaged employees.

Why, then, do senior executives who tout the value of employee engagement so often delegate it to the HR department? HR serves an important function, but not even the best HR staff is in a position to take the actions required to affect the attitudes of individual employees or teams.

And employee engagement remains a challenge for companies worldwide. Recently, Bain & Company, in conjunction with Netsurvey, analyzed responses from 200,000 employees across 40 companies in 60 countries and found several troubling trends:

Engagement scores decline with employee tenure, meaning that employees with the deepest knowledge of the company typically are the least engaged.

Engagement scores decline as you go down the org chart, so highly engaged senior executives are likely to underestimate the discontent on the front lines.

Engagement levels are lowest among sales and service employees, who have the most interactions with customers.

Yet some companies manage to buck these trends. IT-hosting company Rackspace, for instance, has a mantra of “fanatical” customer support. Energized, motivated “Rackers” put in the discretionary effort that creates a superior experience for customers. In turn, customers reward Rackspace with intense loyalty, contributing to the company’s 25% compound annual revenue growth and 48% profit growth since 2008.

Rackspace and other leading companies invest heavily in creating a culture of employee engagement. But what are their secrets?

Line supervisors, not HR, lead the charge. It’s difficult for employees to be truly engaged if they don’t like or trust their bosses. Netsurvey’s data shows that 87% of employee “promoters” of their companies also give their direct supervisors high ratings.

That’s why it’s critical for supervisors to treat team engagement as a high priority — and why their bosses, the senior executives, can’t merely prescribe rote solutions. Instead, senior leaders give supervisors the responsibility and authority to earn the enthusiasm, energy, and creativity that signal deep employee engagement.

Supervisors learn how to hold candid dialogues with teams. Not every supervisor is a natural at engaging employees, so leading companies provide training and coaching on how to encourage constructive discussions with team members. Trainers prepare them to handle sensitive topics like requests for better pay or worries about outsourcing. The training also stresses the importance of taking the right actions quickly and then telling employees how their input contributed to the improvements.

They also do regular “pulse checks.” Short, frequent, and anonymous online surveys (as opposed to a long annual survey) give supervisors a better understanding of team dynamics and a sense of how the team believes customers’ experiences can be improved. What matters most, however, is not the metrics but the resulting dialogue. At AT&T, executives don’t distribute survey scores to line supervisors or their bosses; instead, they show only trends and verbatim feedback. This signals that discussing and addressing the root causes of issues — and seeing steady progress — matter more than any absolute score.

Teams rally ‘round the customer. Call center representatives, sales specialists, field technicians, and others on the front line know intimately which aspects of the business annoy or delight customers. The companies that regularly earn high employee engagement tap that knowledge by asking employees how the company can earn more of their customers’ business and build the ranks of customer promoters. And they don’t just ask; they also listen hard to the answers, take action, and let their employees know about it.

For example, AT&T has built a digital infrastructure enabling all employee suggestions to be logged online. A small, dedicated team regularly reads and triages the suggestions, sending each promising one to a designated leader or expert who is obligated to consider it and respond. Employees can see the progress of each suggestion and log comments. Other companies have developed systems that enable employees to “vote up” or “vote down” the ideas suggested by others, with the best ones getting the attention of the leadership team.

Most companies today spend tremendous amounts of time and effort measuring and addressing issues related to employee engagement. But the results are generally underwhelming. To get a higher return on these resources, it’s time for executives to turn their current approach upside down. Open up the dialogue between employees and their supervisors. Put teams in charge, and let the center provide support. That’s what it takes to help your employees get so fired up that they approach their jobs with energy, enthusiasm, and creativity.

Jon Kaufman, a Bain & Company partner based in New York, contributed to the research and analysis mentioned in this post.

January 24, 2014

We Can’t Afford to Leave Inequality to the Economists

Americans are about as likely to move from one income quintile to another as they used to be. That, put as prosaically as possible, was the big economic news of the week, as the epic income-mobility study led by Harvard’s Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, UC Berkeley’s Patrick Kline and Emmanuel Saez, and the U.S. Treasury Department’s Nicholas Turner generated another data-rich installment.

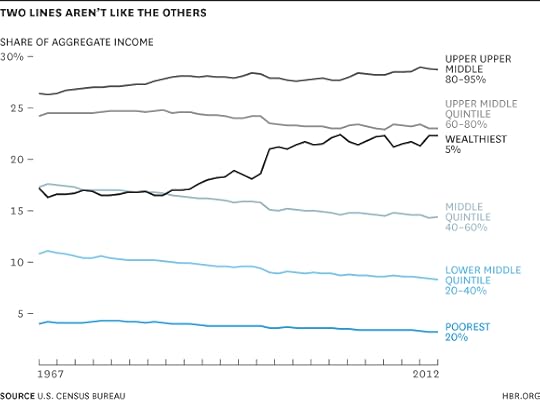

Yet when it comes to the income distribution in the U.S., quintiles are so 1970s. All the really interesting things over the past few decades have been happening in the top 20%. Consider this chart, which shows the share of aggregate income going to each of the bottom four income quintiles, to those between the 80th and 95th income percentiles, and to the top 5%.

The lines for the bottom four quintiles — 80% of American households — are pretty much parallel, showing almost no change in their relative positions. If you just look at the bottom 80% of the income distribution, then, there’s been no significant increase in income inequality. You do see a steady decline in the share of national income going to the bottom 80%, but in absolute terms, incomes for this group are up modestly over the same period.

Things look a lot different up in the top 20% of the income distribution, the part that’s been getting a rising share of aggregate income. The bottom three-quarters of this quintile (those between the 80th and 95th income percentiles) have grabbed some of that, but the really big gains have gone to the top 5%.

And of course it doesn’t stop there. The Census Bureau survey data used in the above chart doesn’t get more granular than the top 5%. But the aforementioned Emanuel Saez, together with Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics, has for the past decade-plus been using income tax records to compile a rich account of what’s been going on up there in the top 1%. You’re probably familiar with the basic outlines, but it’s worth throwing out a few numbers from their most recent update:

From 1993 to 2013, incomes of the bottom 99% of taxpayers in the U.S. grew 6.6%, adjusted for inflation. The incomes of the top 1% grew 86.1%.

The top 0.1% of U.S. taxpayers claimed 11.33% of overall income in 2012, up from 2.65% in 1978. The top 0.01% got 5.47%, up from 0.86% in 1978.

The average income of the top 0.01% was 859 times that of the bottom 90% in 2012. In 1973 the top-0.01%-to-bottom-90% ratio was just under 80.

Something really dramatic is going on up there in the top 5%, the top 1%, the top 0.01%. But while economists know some things about the impact of increasing overall income inequality, they still don’t know all that much about what this 1% stuff means. In their new paper, Chetty, Hendren, Kline, Saez, and Turner write that their finding of steady intergenerational income mobility “may be surprising in light of the well-known negative correlation between inequality and mobility across countries.” A possible explanation, they continue, is that

[M]uch of the increase in inequality has been driven by the extreme upper tail … [and] there is little or no correlation between mobility and extreme upper tail inequality — as measured e.g. by top 1% income shares — both across countries and across areas within the U.S. Instead, the correlation between inequality and mobility is driven primarily by “middle class” inequality.

That’s the thing about this rise in “extreme upper tail inequality” — most pronounced in the U.S. but by now a clearly global phenomenon. It is one of the most dramatic economic developments of the past quarter century. And it seems like it might be bad thing. But conclusive economic evidence for its badness is hard to find.

Yes, there are theories: All that wealth sloshing around in the top 1% leads to more bubbles and crashes. Extreme wealth corrupts the political process. Income inequality may be slowing overall economic growth. And, as my colleague Walter Frick put it in an email when I brought this up, “given the diminishing marginal utility of income, it’s hugely wasteful for the super rich to have so much income.”

I happen to believe there’s some truth to all four of those. But there are also lots of counterarguments and some counterevidence, and big economic studies like the new one by Chetty & Co. don’t seem to be doing much to resolve the debate.

Which leads me to another theory: I think we’re eventually going to have to figure out what if anything to do about exploding high-end incomes without clear guidance from the economists. This is a discussion where political and moral considerations may end up predominating. And as Harvard’s Greg Mankiw made clear in his maddeningly inconclusive Journal of Economic Perspectives essay on inequality last summer, these are areas in which economists possess no comparative advantage.

The Unspeakable Davos

“Oh, you’re a Davos virgin!” a colleague teased me last year upon learning that I was about to join, for the first time, the contingent of academics, journalists, artists, and public servants who orbit around the rich and powerful at the Alpine gathering of the World Economic Forum.

I quipped back that I’d let her know if I enjoyed it, but the metaphor has stuck with me. It captured the mix of curiosity, self-consciousness and trepidation that I felt, and the questions of what precautions I should take and how to talk about it — if at all.

I was reminded of those mixed feelings and hesitation again this year, on the bus to my second Davos, watching my Twitter feed split into parallel streams of contempt and curiosity, both aimed at and flowing from my destination.

I was reminded once more in the conference center, where concurrent panels tackled the promise of “embracing hyper-connectivity” and the perils of the “Big Brother problem.” So one had to choose what to (literally) stand for, instead of debating, say, what embracing Big Brother may entail.

Time and again the answer to my question about what voice to speak with seemed to be clear: either the advocate’s or the critic’s. Unless you are Bono, the only Davos Man whose tough love other delegates crave, you better take sides or else shut up.

That is revealing. And it is a problem.

Ironically, every other article about Davos references “The Magic Mountain,” Thomas Mann’s literary triumph of symbolism and ambivalence—at once a cautionary tale about the dangers of elitist idleness in the face of social change and a reminder of the transformative power of retreats and chance encounters.

While Davos critics tend to evoke the former and most enthusiasts privilege the latter, few focus on the novel as a manifesto for ambivalence, and in particular for a form of ambivalence—skeptical optimism—far too neglected in a world fixated with leaders’ charisma and convictions and followers’ enthusiasm or contempt for them.

Skeptical optimism lets us question ourselves and others, and ourselves with others, without splitting others into allies and enemies. It is borne out of realistic assessments of circumstances and personal limitations, and it lets us keep faith that we can be and make things better without losing ourselves in our faith. It takes failure and betrayal into account, and yet refuses to take either for granted.

Unfortunately, skeptical optimism is hard to sustain for and towards leaders these days. Whether we use the word ‘leader’ to refer to country presidents and CEOs or to our supervisors, idealization and mistrust feel like much safer bets with such uncertainty ahead and so much disillusionment behind us.

Take Davos again, with its optimistic intent to bring influential people together to make progress on the world’s pressing problems—inequality, nationalism, unemployment, poverty, privacy and the like.

It is easy to be inspired by that intent in principle and even easier, in light of the world’s troubles, to view it as a façade for a Versailles of capitalism—a triumph of self-interest where entitled and wannabes mingle in anxious symbiosis—or a one-stop-shop where CEOs can pack in dozens of meetings and save on private jet fuel.

On the inside, however, those monolithic images fracture into a kaleidoscope of smaller gatherings. A multitude of Davos-es with such range of intents and moods—from selfless to instrumental, from argumentative to collaborative—that it is possible for anyone, at any given moment, to feel both an “insider” and an “outsider.”

It is a community I would call Dantesque if the characters in the Divine Comedy switched circles throughout the day in a whirlwind of virtue, temptation, curiosity and fear of missing out.

(And what to make of the literature-loving friend back home who read a draft of this essay and fretted that referencing Dante, compulsory reading in every Italian high school, made me sound elitist—rather than, well, Italian? Another push to take sides?)

The sheer size and scope of the event, and its cramped confines, make the collision of usually distant orbits inevitable. The result is not just serendipitous networking—but emotional friction.

That phenomenon is not unique to Davos, but it is a rare occurrence for leaders who spend much of their time in fairly secluded circles and often have enough power to choose or to avoid who they engage with.

That is the kind of power the Internet has democratized these days, allowing all of us to seclude ourselves in cultural tribes with reassuringly clear worldviews. It is a blinding power. It feeds us enthusiasm and contempt but starves us of curiosity and troubling challenges—and of the learning that both might afford.

This is the real privilege of Davos, subtler and far less visible than the handshakes and parties that are so easy to mock or brag about: the opportunity to meet and learn about, from, and with people who—unlike in most large gatherings like academic conferences, business or political conventions (or Facebook)—are far from your field, industry, and worldview. It is in those encounters, where the other is met with curiosity rather than suspicion, and assurance on occasion gives way to self-doubt, that skeptical optimism is most alive.

These remarkable moments are the best Davos has to offer. Its revealing limitation is how difficult it is to own up and speak with skeptical optimism in public, perhaps for fear of looking doubtful and weak as leaders, of being disappointed and betrayed as followers or simply of no longer knowing which and whose side we are on.

And yet we need skeptical optimism in order to lead and follow responsibly. Turning it into a private privilege makes us both less trusting and less trustworthy. It keeps leaders making bold promises instead of working to regain trust. It keeps followers demanding hopeful visions instead of harsher truths. It locks us in a cycle of elevating and denigrating leaders that even when it gets us different ones still leaves us with the same kind of leadership—to the benefit of the status quo.

Elites can be disturbingly impermeable even without gathering on a mountaintop. They would still give speeches, make deals and throw outlandish parties. If such gatherings did not exist, however, they might be even more isolated and remote.

Davos makes leaders more visible—the hypocrisy of those whose deeds betray their words more obvious. It also makes their circles broader, and makes challenges to their views a little harder to ignore. It creates opportunities for people who may never meet in person to learn with and from each other, and even to confront their relationship with power—others’ as well as their own. That may not change the world, but it might plant a healthy seed of doubt.

Let us hope skeptical optimism comes out of the shadow of bold pronouncements—at Davos and elsewhere. That is one privilege we all could hear—and use—more of.

Yes, Your Company Can Wipe Your Personal Phone (for Now)

The most common complaint the nonprofit National Workrights Institute receives from workers is phone wiping — companies remotely clearing out the contents of personal smartphones that employees sometimes use for work purposes. In fact, a recent survey by Acronis found that 21% of companies "perform remote wipes when an employee quits or is terminated." Why is this happening? More and more companies require workers to be connected when they leave the office, though that doesn't necessarily mean the employers are providing phones to be connected on. One person interviewed for the article bought an Android phone because he felt he was missing out on "late-night notices of meeting changes and other information." When he was fired, the company deleted the contents of his phone. An employee from another company lost photos of a relative who had died.

So what's the way forward, as work and personal lives become more intertwined? Even though companies sometimes lay out agreements in contracts or insert "I agree" buttons into work-related apps or programs, a leading human-resources organization told its members that phone wiping "will likely be tested in the days and months ahead." In the meantime, it's suggested that workers who enter into “bring your own device” agreements back up their personal data regularly, without compromising company information. And businesses should be very clear about what will happen if a worker leaves or is terminated.

Big Data's Big HeartHow a Math Genius Hacked OkCupid to Find True LoveWired

The great potential of Big Data is that there's just so much of it. Of course, that's also its fatal flaw. How do you even begin to collect it, sort through it, and make sense of it? If you're mathematician Chris McKinlay, you create bots and algorithms. Frustrated by dating site OkCupid's failure to match him with suitable partners, he wrote automated dummy profiles to figure out what the women he wanted to meet were looking for, then optimized his own real profile to connect with them. But writer Kevin Poulsen includes an important caveat for any Big Data wannabe: The numbers are just the beginning. Success is what you do with the data. In McKinlay’s case, that means going on dates — a lot of them — and when something clicks, trying like hell to make it work. —Sarah Green

Sorry, Lone WolvesWhy Are American Colleges Obsessed With 'Leadership'?The Atlantic

Do U.S. universities, and in particular top-notch institutions like Harvard and Yale, place too much emphasis on leadership potential when they screen applicants? It's a question posed by Tara Isabella Burton, and she doesn't have concrete answers. But her analysis is nonetheless worth reading in full, and, generally speaking, she comes away with two concerns. To start, why is being a leader (and to be clear, what "leader" means isn't clear at all) prioritized over being a lone wolf or merely a participant or follower? All of these types are contributors to society and work, though Burton posits that being a "contributor" is equated with being average.

Second, are U.S. universities penalizing "candidates from different cultural backgrounds, where leadership — particularly among adolescents — might take different forms, or be discouraged altogether"? Burton's experience at Oxford, where lone-wolf researchers are held in high regard, is just one example of this. She suggests that U.S. institutions rethink their leadership emphasis. "Do we need a graduating class full of leaders? Or should schools actively seek out diversity in interpersonal approaches — as they do in everything else?"

Melting Away The Health Hazards of Sitting The Washington Post

Want to know exactly what's happening to your body as it deliquesces during each work day, turning to mush as you stare into your computer? Then take a good look at this lovely graphic, which shows your muscles degenerating, your bones getting soft, your pancreas giving you diabetes, your colon developing cancer, your back seizing up as your discs are squashed unevenly, and your life ticking away to an untimely end. The real solution to the hazards of sitting is probably to get a job on a shrimp boat, but if you can't do that, you can try standing up more at work and doing a few yoga poses. Flex your back. Stretch your hips. You can also get some exercise pinning this graphic to the wall of your cube — it's downloadable as a poster. —Andy O'Connell

It's Not Just a BusinessOld McDonald'sThe New York Times

In case you missed the brouhaha, a McDonald's in Queens, New York, made headlines when the manager called police to remove a group of elderly Korean-Americans who would spend hours sitting in the restaurant talking and eating minimal amounts of food. In this follow-up op-ed, sociology PhD candidate Stacy Torres argues that businesses should accommodate — rather than shun — this type of social congregation. "For retirees on fixed incomes who may have difficulty walking more than a few blocks, McDonald's restaurants remain among the most democratic, freely accessible spaces," she says. These locations are what sociologist Ray Oldenburg calls "third places," after work and home. Fast-food restaurants, cafés, and bookstores offer "necessary yet endangered meeting points to foster community, especially among diverse people." Torres says we should "praise companies that allow loitering and devise public-private partnerships that benefit both older adults and business owners."

BONUS BITSAu Contraire

Bill Gates Says the World is Getting Vastly Better (Fast Company)

High-Tech Immigrant Workers Don't Cost U.S. Jobs (Working Knowledge)

Research: Don’t Offshore Your R&D

Just because a company can offshore some portion of its operations doesn’t mean it should. The benefits might come in the form of easily recognized savings on the balance sheet, but the costs may accrue over time in the more obscure form of added organizational complexity.

That appears to be the case with the offshoring of research and development, according to a new paper from the Center for European Economic Research. Offshoring some portion of a firm’s innovation may be beneficial, the authors argue, but beyond a certain point it becomes counterproductive.

As global competition has pressured firms to move portions of their businesses overseas, some have gone so far as to offshore research, development, and design. With nations like China ramping up their innovative capacities, why stop at offshoring manufacturing or customer support? This trend has caught the attention not just of the business world, but of the governments of many developed nations, which fear that such a shift would erode their competitiveness.

That concern may be overstated, given the downsides of offshoring innovation that new research reveals.

“It is commonly held that off-shoring requires also organizational restructuring,” the authors write, but there is disagreement about its effects. One side argues that offshoring “increases organizational complexity and hence reduces the organizational ability to adapt to changing environments” while the other suggests that it may unlock new sources of knowledge, or improve performance by focusing employees on smaller chunks of a problem.

So the researchers set out to test these arguments, using survey data from a wide range of German companies. They examined the relationship between offshoring of innovation and “organizational adaptability” – the ability of a firm to change organizational routines and processes in a way to improve the firm’s performance, measured by things like developing new products, reducing costs and reaction times, and improving quality and communication.

After adjusting for several other variables, the result was the inverted U-shaped curve below, suggesting that offshoring innovation can be beneficial, but only up to a point, after which it begins to hinder a firm’s adaptability:

(The Y-axis is looking at the probability that a company at any given level of offshoring doesn’t score in the lowest category for adaptability. In other words, the odds that it has maintained some bare minimum level of adaptability.)

The findings suggest that the optimal amount of offshoring differs depending on the activity, with much more leeway for shifting product design abroad than for core R&D or downstream activities including “production of new products/services, introduction of new process technology, [and] marketing of new products/services.”

The takeaway, the authors write, is that offshoring too much of a firm’s innovation is likely to be costly:

Our findings hence imply a trade-off between global knowledge sourcing and a firm’s ability to use this knowledge effectively. The empirical results suggest that off-shoring more than 15 to 30% (depending on the type of innovation) of a firm’s innovation activities becomes challenging for maintaining the effectiveness of the organization.

And:

The threshold level is lower for innovation activities that are more closely related to core functions of the firm, i.e. R&D and marketing of innovation. If a substantial part of these activities take place at firm locations abroad, coordination costs increase and organizational changes become more complex.

In practice, most firms in the sample were at or below the optimal threshold for offshoring of innovation. But within the subset that did choose to offshore core R&D, nearly 40% had exceeded the optimal level. Interestingly, smaller firms seemed less adversely affected by the offshoring of innovation, which the authors suggest may be due to greater organizational flexibility.

But for most firms, the paper’s findings are worth bearing in mind. As the authors conclude, “Keeping most R&D activities at the home base is beneficial in a world where innovation cycles become shorter and developing new technologies more challenging.”

The Largest Risk (and Opportunity) Investors Are Ignoring

Tackling climate change — and thus keeping the world inhabitable — is an achievable goal, but it will become prohibitively expensive if we wait to act. This is the key message from a leaked United Nations study that The New York Times reported on last week. Journalist Justin Gillis wrote about the risk of “severe economic disruption” and “wildly expensive” solutions — ones that may not even exist — if we don’t leverage existing technologies to shift the global economy away from carbon over the next 15 years.

Talk of potential risk to humanity is not new. And we’ve seen more recently the actual devastation of record weather events like Hurricane Sandy and Typhoon Haiyan. But neither the scientific warnings nor the extreme storms have prompted enough action. However, now the risk we’re talking about is financial, which, along with the enormous economic upside of taking action, may finally get the investment community moving.

The day before the stark story in the Times appeared, I attended a related conference, the Investor Summit on Climate Risk, held at the UN and run by the NGO Ceres. Hundreds of financial executives gathered, including some heavy-hitters, from state comptrollers to executives from large pension funds to former U.S. treasury secretary Robert Rubin, who declared, “climate change is an existential risk.”

The conference was focused on the release of Ceres’ new report, “Investing in the Clean Trillion.” Created in conjunction with Carbon Tracker, the study lays out a plan for mobilizing much more capital toward building the clean economy. The trillion-dollar number is not random: The International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that the world needs to pour $36 trillion of investment into the clean economy between now and 2050 in order to keep the planet below the critical warming threshold of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2oC). That’s $1 trillion per year.

A key target for Ceres’ work, and the main audience at the conference, is the group of institutional investors who manage tens of trillions of dollars in assets for long-term performance. The core argument to compel institutional investors to change how they influence companies and where they invest their money is simple: as the world pivots away from carbon-based energy to avoid devastating climate change, fossil fuel assets, like coal plants or off-shore oil rigs, will be “stranded” — a wonky term for “worthless.” The value of the companies owning and managing those assets, the logic goes, will plummet. As Nick Robins from the bank HSBC described to the audience, in a scenario of global peak fossil fuel use by 2020 “implies a 44% reduction in discounted cash flow value of fossil fuel companies” — or in simpler terms, a decline in share price of 40 to 60 percent.

In another Ceres meeting last fall on this topic of stranded assets, Craig Mackenzie from the Scottish Widows Investment Partnership ($200 billion in assets) spoke about the “wake-up call” investors had gotten from recent shifts in the U.S. coal market. The 20% drop in coal demand was driven mainly by the incredible increase in natural gas production due to fracking technology, not from any concern over greenhouse gases. But the rapid shift demonstrated to Mackenzie and his firm the dangers of overexposure to a class of assets. So, he says, the fund “reduced exposure to pure play coal companies to nearly zero.”

It’s easy to point out a big flaw with the stranded assets discussion: uncertainty. I spoke with executives at a few big banks who said the big question for them is when will the assets be stranded. Nobody wants to leave profitable investments too early that gets you fired. But trying to time a bubble bursting is a dangerous game. How many investors got the timing right on the implosion of mortgage-backed security assets in 2008? Nearly none, and that systemic failure of vision contributed mightily to a global financial collapse.

Given what’s at stake now — not just financial system stability, but planetary, human-supporting system stability – it’s more than prudent to avoid the game of timing the market perfectly. The investment community should be much more proactive about using its weight to a) pressure fossil fuel companies to quickly migrate their own portfolios to new forms of energy; and b) dedicate significant funds to investing directly in new technologies.

With the chilling, “it’s going to be very costly” message of Gillis’ article, and the warnings of trillions of stranded assets in the Ceres report, it’s easy to miss the very big silver lining running underneath all the dire warnings: we have the technologies today to make the shift and do it profitably.

The Clean Trillion report cites the uplifting flip side of the IEA’s calculations — the $36 trillion of investment we need will yield $100 trillion in fuel savings between now and 2050. That’s a lot of money to leave on the table, and a very good investment.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers