Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1481

January 23, 2014

Say “No” to Innovation-in-General

I had just arrived at a conference on entrepreneurship and the only panel I wanted to see was starting. I looked down at my watch and realized that I was already 5 minutes late so I dropped my bags and ran to the next building.

The subject was intrapreneurship and it seemed like the organizers had collected an all-star panel; two Googlers, an early Facebooker, one of the recent additions to the Paypal team, and one of the IBM leads on the Watson project. For over an hour, the panel discussed all of the innovative projects they’d worked on — spanning projects from Google Fiber to ad bidding technologies at Facebook.

Now, while I can’t speak for everyone else in the room, I found myself leaving the discussion disappointed.

Yes, all of the panelists were speaking broadly on innovative projects. But innovation is a word that means a wide variety of things to a wide variety of people. Without more specification, “innovation” is simply too broad to execute against. It’s like talking about creating art, without specifying between medium. Are you painting, sculpting, filmmaking, or rapping?

At its highest level, innovation is simply where ideation meets commercialization. Innovation is both the new color of Crayola crayon as well as the iPad app that completely replaces the need for Crayola crayons in the eyes of children everywhere. Because of the vast space between these, the astute manager shouldn’t simply aspire to innovation in general. It doesn’t give his team enough to go on. One employee might come back with a thousand different colors for new crayons, while another suggests strategic adjacencies with construction paper, while the final suggests a partnering with Adobe to deliver a drawing application. Yes all three are innovative. But simply claiming that they are innovative projects neglects the point that they really are entirely different in nature.

Without differentiating between things like sustaining and disruptive innovations, the conversation never directs managers to the nitty-gritty details where new products and services live or die.

It’s no wonder there is such widespread backlash against innovation today. Everyone from the Wall Street Journal to Techcrunch has an opinion on innovation overload. But I’d argue that the real problem with our innovation zeitgeist isn’t that the quality of ideas is diminishing, it’s that we’re talking about the bold audacious bets in the same way we’re talking about the unheralded incremental ones. We’re considering little league and Major League baseball the same, just because they’re both baseball.

In the research world, innovation is a term one rarely hears in a vacuum. Instead of rolling off the tongue by itself, academics modify the term innovation with all sorts of other words that specify exactly what phenomenon they’re talking about. And while not all lessons from academia do apply to the business world, this is certainly one place that hard-nosed managers and pointy-headed intellectuals should agree; because when it comes to innovation, our muddled-generic language represents muddled-generic thinking — not the clarity of thinking that should be driving multi-billion dollar investment decisions.

It’s easy to poke fun at the lengthening list of specific types of innovation, from Continuous to Reverse to Sustaining to Disruptive to Platform and beyond. But as we accept that leadership comes in many forms, from managing crises to coaching employees, we need to do the same when it comes to innovation.

Our lack of thoughtfulness on the subject has kept us from investing and concentrating on the innovations that matter most. Increased attention on innovation by businesspeople has led to millions more executives with “innovation” in their sights, but far fewer with a deep understanding of what the word means.

Innovation simply isn’t one thing. It’s a wide variety of things. It’s the sustaining innovations that will drive profitability across your core business units. It’s the continuous technological innovations that will exploit your fixed asset base. It’s the disruptive innovations that will help you drive your business into the next era of your industry’s evolution. It’s the reverse innovations to help you penetrate new markets and return lessons from different geographies.

And your business needs all of it. But each aspect of it needs to be managed distinctly. Build a shared language for innovation in your organization, set up the structures to pursue each type of innovation correctly, and invest in the team that can guide you through the process.

If you’re feeling burned out on innovation, don’t let your new years resolution be to say no to innovation… let it be to say no to innovation-in-general.

January 22, 2014

Cracking the Code That Stalls People of Color

It’s a topic which corporations once routinely ignored, then dismissed, and are only now beginning to discuss: the dearth of professionals of color in senior positions. Professionals of color hold only 11% of executive posts in corporate America. Among Fortune 500 CEOs, only six are black, eight are Asian, and eight are Hispanic.

Performance, hard work, and sponsors get top talent recognized and promoted, but “leadership potential” isn’t enough to lever men and women into the executive suite. Top jobs are given to those who also look and act the part, who manifest “executive presence” (EP). According to new CTI research (PDF), EP constitutes 26% of what senior leaders say it takes to get the next promotion. Yet because senior leaders are overwhelmingly Caucasian, professionals of color (African-American, Asian, and Hispanic individuals) find themselves at an immediate disadvantage in trying to look, sound, and act like a leader. And the feedback that might help them do so is markedly absent at all levels of management.

EP rests on three pillars: gravitas (the core characteristic, according to 67% of the 268 senior executives surveyed), an amalgam of behaviors that convey confidence, inspire trust, and bolster credibility; communication skills (according to 28%); and appearance, the filter through which communication skills and gravitas become more apparent. While they are aware of the importance of executive presence, men and women of color are nonetheless hard-pressed to interpret and embody aspects of a code written by and for white men.

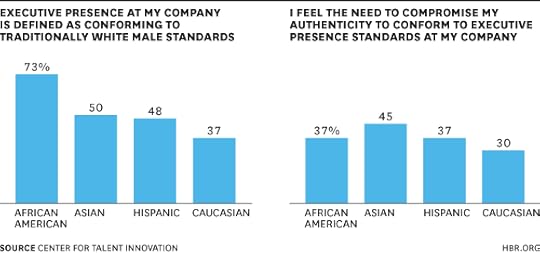

CTI research finds that professionals of color, like their Caucasian counterparts, prioritize gravitas over communication, and communication over appearance. Yet, “cracking the code” of executive presence presents unique challenges for professionals of color because standards of appropriate behavior, speech, and attire demand they suppress or sacrifice aspects of their cultural identity in order to conform. They overwhelmingly feel that EP at their firm is based on white male standards — African Americans, especially, were 97% more likely than their Caucasian counterparts to agree with this assessment — and that conforming to these standards requires altering their authenticity, a new version of “bleached-out professionalism” that contributes to feelings of resentment and disengagement. People of color already feel they have to work harder than their Caucasian counterparts just to be perceived “on a par” with them; more than half (56%) of minority professionals also feel they are held to a stricter code of EP standards.

EP further eludes professionals of color because they’re not likely to get feedback on their “presentation of self.” Qualitative findings affirm that their superiors, most of whom are white, hesitate to call attention to gravitas shortfalls and/or communication blunders for fear of coming across as racially insensitive or discriminatory. While sponsors might close this gap, specifically addressing executive presence issues with their high-potentials, CTI’s 2012 research shows that professionals of color are much less likely to have a sponsor than Caucasians (8% versus 13%). When they do get feedback, they’re unclear as to how to act on it, particularly if they were born outside the U.S. — a serious problem for corporations who need local expertise to expand their influence in global markets.

In short, because feedback is either absent, overly vague, or contradictory, executive presence remains an inscrutable set of rules for professionals of color — rules they’re judged by but cannot interpret and embody except at considerable cost to their authenticity. Consequently, in a workplace where unconscious bias continues to permeate the corridors of power, and leadership is mostly white and male, professionals of color are measurably disadvantaged in their efforts to be perceived as leaders.

As America becomes more diverse at home and its companies are increasingly engaged in the global marketplace, winning in today’s fiercely competitive economy requires a diverse workforce that “matches the market.” Such individuals are better attuned to the unmet needs of consumers or clients like themselves. New research from CTI (PDF) shows, however, that their insights need a key ingredient to reach full-scale implementation: a cadre of equally diverse leaders. Yet the power of difference is missing at the top, just when it matters most.

Editor’s note: We updated the headline and body of this post January 23. The original post referred to professionals of color as “multicultural professionals.” We regret the error.

Cracking the Code That Stalls Multicultural Professionals

It’s a topic which corporations once routinely ignored, then dismissed, and are only now beginning to discuss: the dearth of multicultural professionals in senior positions. Multicultural professionals hold only 11% of executive posts in corporate America. Among Fortune 500 CEOs, only six are black, eight are Asian, and eight are Hispanic.

Performance, hard work, and sponsors get top talent recognized and promoted, but “leadership potential” isn’t enough to lever men and women into the executive suite. Top jobs are given to those who also look and act the part, who manifest “executive presence” (EP). According to new CTI research (PDF), EP constitutes 26% of what senior leaders say it takes to get the next promotion. Yet because senior leaders are overwhelmingly Caucasian, multicultural professionals (African-American, Asian, and Hispanic individuals) find themselves at an immediate disadvantage in trying to look, sound, and act like a leader. And the feedback that might help them do so is markedly absent at all levels of management.

EP rests on three pillars: gravitas (the core characteristic, according to 67% of the 268 senior executives surveyed), an amalgam of behaviors that convey confidence, inspire trust, and bolster credibility; communication skills (according to 28%); and appearance, the filter through which communication skills and gravitas become more apparent. While they are aware of the importance of executive presence, multicultural men and women are nonetheless hard-pressed to interpret and embody aspects of a code written by and for white men.

CTI research finds that multicultural professionals, like their Caucasian counterparts, prioritize gravitas over communication, and communication over appearance. Yet, “cracking the code” of executive presence presents unique challenges for multicultural professionals because standards of appropriate behavior, speech, and attire demand they suppress or sacrifice aspects of their cultural identity in order to conform. They overwhelmingly feel that EP at their firm is based on white male standards — African Americans, especially, were 97% more likely than their Caucasian counterparts to agree with this assessment — and that conforming to these standards requires altering their authenticity, a new version of “bleached-out professionalism” that contributes to feelings of resentment and disengagement. People of color already feel they have to work harder than their Caucasian counterparts just to be perceived “on a par” with them; more than half (56%) of minority professionals also feel they are held to a stricter code of EP standards.

EP further eludes multicultural professionals because they’re not likely to get feedback on their “presentation of self.” Qualitative findings affirm that their superiors, most of whom are white, hesitate to call attention to gravitas shortfalls and/or communication blunders for fear of coming across as racially insensitive or discriminatory. While sponsors might close this gap, specifically addressing executive presence issues with their high-potentials, CTI’s 2012 research shows that multiculturals are much less likely to have a sponsor than Caucasians (8% versus 13%). When multiculturals do get feedback, they’re unclear as to how to act on it, particularly if they were born outside the U.S. — a serious problem for corporations who need local expertise to expand their influence in global markets.

In short, because feedback is either absent, overly vague, or contradictory, executive presence remains an inscrutable set of rules for multiculturals — rules they’re judged by but cannot interpret and embody except at considerable cost to their authenticity. Consequently, in a workplace where unconscious bias continues to permeate the corridors of power, and leadership is mostly white and male, multiculturals are measurably disadvantaged in their efforts to be perceived as leaders.

As America becomes more diverse at home and its companies are increasingly engaged in the global marketplace, winning in today’s fiercely competitive economy requires a diverse workforce that “matches the market.” Such individuals are better attuned to the unmet needs of consumers or clients like themselves. New research from CTI (PDF) shows, however, that their insights need a key ingredient to reach full-scale implementation: a cadre of equally diverse leaders. Yet the power of difference is missing at the top, just when it matters most.

So You Want to Build an Internet of Things Business

Earlier this month, Google made headlines by acquiring Nest Labs, the connected home startup, for $3.2 billion in cash. Although Nest has received significant fanfare for its smart products, some have argued that the price is a very generous premium for a small company that only a year ago was valued at $800 million. But, perhaps more importantly, why would Google — given its track record of market successes, strong design and engineering talent, and unique brand reputation — choose to buy its way into the Internet of Things (IoT)?

Perhaps because it is really hard to create organic growth through connected devices. It requires linking physical product and software experiences – designing for convergence – in a way that few large companies have done successfully to date. While many companies have explored home automation, connected car, and wearables, the practical realities of building and scaling an ecosystem of connected products and services are more challenging than most senior executives realize. And getting the convergence wrong can have serious implications for a company’s bottom line and market reputation.

More specifically, designing for convergence involves three big challenges. Any of them individually is difficult — but to build a successful IoT business, a company must manage to do them all well.

Connect Vision to Real Customer Needs

It’s exciting to envision futuristic scenarios in which previously analog products come to life. How could they all turn “smart,” and exchange information with each other in interesting ways? But the most compelling value propositions usually start with a focus on a single customer pain point. Mike Slattery, VP of Connected Car for AAA Club Partners, knows this. “When we built SMARTtrek, our connected car platform, we knew there were many potential scenarios to solve,” he says. “But we focused on one meaningful service – combining roadside assistance, repair, and auto insurance – to create a unique connected experience. SMARTtrek provides location assistance to help us quickly dispatch and find our members, as well as insights into vehicle diagnostics to troubleshoot and ultimately provide the best possible repair experience.”

Whether your IoT vision revolves around cars, thermostats, refrigerators, or anything else, make sure you’re focusing on a problem to which customers want a better solution. Then figure out how that problem can be solved in a simple, intuitive way through an integrated hardware and software platform.

Integrate Physical and Digital Development

Designing connected experiences requires the integration of very different development skill sets and processes. First, you need hardware production, which calls for product design and engineering in a linear, often lengthy development cycle. Second, you need digital and software design, which happens in short, modular development loops and requires support from different kinds of designers (for example, specialists in user interaction) and programmers. While both hardware and software depend on good design to succeed, the approaches are like night and day – and being great at designing for pixels does not easily translate to being great at designing for atoms. Take it from Bug Labs CEO Peter Semmelhack (who has a software background). “Hardware is hard,” he admits in his book Social Machines. “Any disruption in the development of your product will have 3X greater impact on your schedule than you anticipate.”

The implication for most companies is that they rarely have both capabilities. The core strengths are in such contrast that they are rarely resident in one company. This is a huge hole that many large companies encounter in their IoT journeys – and in particular, has seemed to be the downfall of a number of crowdfunded IoT companies, despite their appealing ideas for new IoT offerings.

Bridge Different Business Models

The IoT is leading to new avenues of growth but also threatens how companies have historically made money. Hardware companies traditionally derive profits by balancing product revenues with the costs associated with materials, manufacturing, and fulfillment. On the flip side, digital companies usually leverage service business models, often with recurring revenue streams. For connected devices, the two worlds collide in a confusing way: the hardware company has to begin accounting for the costs of tracking data and supporting a service, while the software company has to start managing the costs of making and distributing physical products.

Steve Blank, the entrepreneur and Lean Startup advocate, has said, “A startup is an organization designed to search for a repeatable and sustainable business model.” As they embark on that hard task, connected device companies are further challenged by the fact that they have an old business model they must successfully transition out of.

Make, Buy or Partner

Back to Google, then – and every large company attempting to build an IoT-based business. They face the challenge of creating a robust hardware company with physical products, plus the complexity of running a service company, too. No doubt they have watched some companies make the transition through internal initiatives and organic growth, but have also noted how most others struggle. A client recently said to me, “The outcome of this effort is a business, not a set of products.” As simple as that statement is, it is hard to wrap an organization around the change it suggests. So expect to see more companies, like Google, decide that acquisitions or select partnerships (like Google’s collaboration with Asus for tablets) are easier routes to building a connected device business.

How to Engage Employees Who Are About to Lose Their Jobs

It’s hard enough to energize people in a merger or an acquisition when they know that they have a good chance of being part of the new organization. But a leader should also strive to win the loyalty and commitment of those who know that they are likely to lose their jobs.

Conventional management thinking often is, “We won’t spend too much time on people whose roles end with the transaction. They are not part of our future.” Nothing could be more mistaken. These colleagues are crucial to a successful transition. They powerfully influence the morale of those who will stay. Importantly, the mind-set of the “leavers’’ can significantly impact the reputation of the enterprise for many years to come, especially today, as social media multiplies the impact of any message.

To truly be a transformative leader in these circumstances, one must go the extra mile to make those who must leave feel like the key employees they are for as long as they are on the team.

Here are two cases that provide some important lessons that have applicability for many situations.

The first concerns a complex transatlantic acquisition of a biotech company by a pharmaceutical company. There were major overlaps in corporate and operational management positions, but most employees would be retained. An urgent challenge was to have all managers — including those who knew or feared they would eventually be terminated — be engaged as dynamic leaders.

The pivotal step occurred when the acquiring company’s CEO held in-person meetings with groups of managers from both companies to express empathy. He explained that he had experienced similar situations and understood that they were not easy. He acknowledged the tough choices and the real stress of uncertainty.

The CEO personally promised managers that they would be treated well, whether they were to leave or stay. He asked them to rise to a big challenge: the need to put aside their own anxieties to reassure and motivate their teams.

The result was galvanizing. Managers said how much they appreciated his candor and empathy. And, judging from employee surveys, most managers rose to the leadership challenge. Their people felt that managers had a revitalized commitment to caring for them and their own faith in their futures with the organization was renewed.

The second case involved the integration of a specialty company into a global pharmaceutical company. After the deal, it quickly became clear that a significant site would have to close, which would result in the loss of hundreds of jobs. Yet, a successful integration would require that the full team remain engaged until site closure occurred many months later.

The management team overseeing the integration recognized that the affected employees cared deeply about the work they did for patients, needed security and a sense of future for themselves and their families, and wanted to be treated with dignity. Meetings were held to forthrightly address the tough reality and to emphasize that the company respected the accomplishments of the departing employees and was sensitive to their personal and professional interests.

Management committed to communicate openly and regularly with employees, to keep them apprised of the planning horizon, to give 60 days’ notice, and to provide enhanced severance. Finally, the importance of continuing to serve the needs of countless thousands of patients was stressed.

Special attention was given to the site’s middle managers who felt both personal anxiety and responsibility for their people. A number of them were given leadership roles in the functional transition teams, which provided the affected employees with a seat at the management table.

Additionally, local managers were enlisted in a campaign to help their people prepare to find new jobs after the site closed. This included workshops on writing resumes and using LinkedIn, and coaching on how to translate skills and experience into new opportunities.

Trust was forged, and it grew. Knowledge and work were successfully transitioned from the site’s workforce to others taking on their jobs and the expected synergy from the merger was captured. Those who remained with the company were proud of how the transition was managed.

As these cases demonstrate, transformative leaders recognize the importance and impact of those who must leave, walk in their shoes, empathetically and candidly engage with them, restore confidence, and renew their sense of purpose. They provide concrete and emotional reasons for the departing to recommit to their current work and build a legacy that they can be proud of after they have moved on. By executing this role with excellence, they help secure the success of the enterprise.

For a Codependent America and China, What Comes Next?

There have been many uncertainties over the past six months that, depending on how things played out, had the power to change what we can expect from the Next China, and what that means for the Next America.

The new leaders of China had their very important policy meeting in early November, the so-called Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. In the US, the government shutdown and ongoing political dysfunction roiled financial markets and raised serious new questions about America’s money-saving potential and the long-term outlook for the US economy. Meanwhile, security tensions have mounted between China and Japan over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, raising the threat of military confrontation between the two Asian powers and their allies.

I watched the news with that anxiety peculiar to nonfiction authors: the fear that one’s topical analysis will be quickly overwhelmed by the sweep of events. That was my worry during the seemingly interminable period that separated my final revisions to Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China, submitted in August 2013, and the actual publication date in late January 2014. As things turned out, developments on these fronts (at least the first two) fit quite well with the central thesis of Unbalanced — that China is firmly on the road to rebalancing while America is not, and that this asymmetrical outcome poses both risks and opportunities for these two codependent nations.

China will shift to more of a consumer-led economy. The outcome of the Third Plenum makes this clear. Prior to that critical policy meeting, a gathering that is held only once every five years in China, the case for the long-awaited rebalancing of the Chinese economy was mainly a conceptual one. China had enacted its 12th Five-Year Plan in March 2011, but it provided more of a framework for economic restructuring than a series of concrete recommendations to speed the shift from the Producer Model of the past to more of a Consumer Society in the future.

That plan placed emphasis on providing new opportunities for Chinese families to boost their spendable incomes – opportunities centered on new sources of job creation in China’s emerging but still embryonic services sector, and higher per-capita incomes that come with urbanization. But there was no guarantee these opportunities would translate into new sources of discretionary consumption. Lacking a social safety net – that is, in light of unfunded retirement and medical care systems – Chinese families understandably remained quite fearful of an insecure future and were more likely to save any newfound income rather than spend it.

The reforms of the Third Plenum address this key shortcoming head on. The focus here was on specific proposals aimed at changing the very behavioral norms that have long stymied the emergence of a more active Chinese consumer. Phasing out the one-child family planning policy is an important case in point. So, too, were specific proposals aimed at reforming the residential permit system (the hukou), which had prevented the portability of social welfare benefits that any modern society needs. Equally encouraging were long awaited signs of an ending of the tight regulation of deposit interest rates for return-starved Chinese savers. The same can be said of a proposal to earmark 30 percent of the profits of China’s vast state-owned enterprises toward funding the nation’s unfunded social safety net programs.

This is a powerful combination – opportunities of job creation and higher incomes provided by the 12th Five-year Plan, and incentives to change behavioral norms of Chinese families by the Third Plenum. This puts China firmly on the road to a consumer-led rebalancing.

But it’s a development that America may not be prepared for. For as China shifts more to consumer-led growth, that means it will continue to draw down its surplus saving, which would, in turn, reduce its current account surplus, limit its accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, and reduce its demand for US Treasuries and other dollar-denominated assets.

That poses several key questions for the United States: With its largest foreign lender focusing more on saving absorption in its domestic economy than on investing its surplus saving in the United States, who will provide saving-short America with the surplus saving it needs in order to grow? In particular, who will take China’s place in helping to fund America’s outsized budget deficit – a question that seems all the more relevant in light of Washington’s latest efforts to keep kicking the fiscal can down the road? And, as China shifts from focusing on production to drawing greater support from internal consumption, who will provide the low-cost goods that hard-pressed middle-class American families now rely on to make ends meet? Finally, note that China is America’s third-largest and most rapidly growing export market. Will US industry be able to seize the opportunities inherent in what could be the world’s greatest consumer story of the 21st century?

Codependency is no way to maintain healthy human relationships. Neither is it sustainable for large economies. As my book went to press, there were plenty of reasons to anticipate an asymmetrical endgame to the codependency between America and China – that China would be the first of the two to move down the road of rebalancing. The questions central to Unbalanced have proved more relevant than ever. Geopolitical wildcards, especially with respect to intensified tensions with Japan but also in light of the ongoing cyberhacking dispute with the United States, also remain to be played, and may make for an even more destabilizing breakup. But that was always the ultimate catch of this codependent relationship. From the start, it was a marriage of convenience – not one based on love.

Three Long-Held Concepts Every Marketer Should Rethink

One of the strongest held beliefs among marketers is that brand plays an important—even crucial—role in consumer decision-making. But recent developments in consumer electronics should make us all stop and think. Consider two examples: Roku, a virtually unknown brand, captured significant market share in the streaming set-top box market. And in the tablet market (the iPad notwithstanding) some reports suggest that “tablet buyers don’t care who makes their devices.” We attribute these phenomena to a fundamental shift in the way consumers make decisions. Let us explain this shift and how it shakes long-held beliefs about three concepts in marketing: brand, loyalty, and positioning.

Brand. In the past, consumers had no way of accurately assessing the real quality of things directly, so they usually evaluated quality based on generic, top-of-mind reference points and quality proxies. One such proxy was the brand name. But brands are less needed when consumers can assess product quality using better sources of information such as reviews from other users, expert opinion, or information from people they know on social media. Reassured by the opinions of others, consumers are less hesitant to try a lesser known brand like Roku. (Roku 3 has 4660 reviews with a 4.5 star average on Amazon.com). The same thing happens in the tablet market where people feel comfortable trying brands such as Acer or Asus instead of well-established brands. And of course, this shift in decision-making is not limited to consumer electronics; it can be seen in the way people shop for cars, hotels, books, restaurants, and many other products and services. The main implication is that it presents newcomers with lower barriers to entry and, as a result, creates more volatility in brand equity (which means that newcomers who are rejoicing as they gain market share should realize that they can fall just as fast).

Loyalty. Another proxy that consumers used to rely on was their past experience with a company. Standing at a computer store in the 1990s, a customer might have looked at a laptop and thought to himself: “In the past, I used a Toshiba laptop that worked fine – so this Toshiba must be good, too.” Since he didn’t have too many alternative sources of information, it made sense to stay loyal to Toshiba (or Sony or Dell). But in a world with good, low-cost information, the customer can easily start from scratch each time. Many marketers still believe in the power of consumer loyalty and the great profitability of even a small increase in the number of consumers declaring themselves “loyal.” But more and more consumers think about their relationships with companies as an open marriage. Loyalty doesn’t benefit the customer as much as it did in the past. Are we saying that this is the end of brand and loyalty? Of course not. Apple, the leader in the tablet and set-top box markets, is a prominent example of that (although its success can also be attributed to offering high-quality products). What we’re saying is that the power of brand and loyalty as the main cues for quality is diminishing.

Positioning. This is another concept that is becoming less relevant as consumers increasingly rely on the opinions of others. Yet many marketers still believe that they can drive product perceptions based on the way they present their products relative to other options. The idea behind positioning is that each marketer has to find an area that is not occupied in the consumer’s mind and capture it. (In automotive, for example, Volvo stood for “safety,” and Toyota captured “reliability.”) But when consumers base their decisions on user and expert reviews, nice positioning statements are less likely to be adopted by the market. It’s simply that reviewers on the Web tend to evaluate multiple features of a product and are not likely to isolate a single attribute just because it was highlighted in a company’s ad campaign. For example, in recent years we’ve seen a couple of attempts to introduce new phones that would be positioned as “the Facebook phones.” But reviewers—and as a result consumers—evaluated all features of these phones (comparing, for example, camera, thickness, and display) and didn’t necessarily put any emphasis on how well the phone works with Facebook. Marketers can save themselves a lot of money by avoiding doomed-to-failure positioning attempts.

When consumers can assess their likely experience without having to rely on things like brand names or prior experience, everything changes. Yet most people think about marketing using the same old concepts. Despite all the talk about the Internet and social media, the presumed critical roles of branding, loyalty, and positioning have not changed. It’s time to seriously reevaluate these and other long-held beliefs about marketing.

What People Really Care About When They Meet You: Are You a Good Person?

When people meet you, their impressions are formed more by their perceptions of your moral character than by your personal warmth (or lack thereof), suggests research by Geoffrey P. Goodwin, Jared Piazza, and Paul Rozin of the University of Pennsylvania. For example, in one study, research participants who were asked for their overall impressions of people rated those who were “cold” but had “good character” more positively than those who were warm but of bad character (5.59 versus 3.60 on a nine-point scale). The researchers’ finding about the importance of moral character—that is, whether you’re a good or bad person—contradicts recent theories that the two fundamental dimensions of perception are warmth and competence.

Does Your Company Make You a Better Person?

When we hear people talk about struggling to maintain work-life balance, our hearts sink a little. As one executive in a high-performing company we have studied explained, “If work and life are separate things—if work is what keeps you from living—then we’ve got a serious problem.” In our research on what we call Deliberately Developmental Organizations—or “DDOs” for short—we have identified successful organizations that regard this trade-off as a false one. What if we saw work as an essential context for personal growth? And what if employees’ continuous development were assumed to be the critical ingredient for a company’s success?

The companies we call DDOs are, in fact, built around the simple but radical conviction that the organization can prosper only if its culture is designed from the ground up to enable ongoing development for all of its people. That is, a company can’t meet ever-greater business aspirations unless its people are constantly growing through doing their work.

What’s it like to work inside such a company? Imagine showing up to work each day knowing that in addition to working on projects, problems, and products, you are constantly working on yourself. Any meeting may be a context in which you are asked to keep making progress on overcoming your own blindspots—ways you are prone to get in your own way and unwittingly limit your own effectiveness at work.

Whether you are someone who avoids confrontation, hides your inadequacies to avoid being found out, often acts before thinking things through, gets overly aggressive when your ideas are criticized, or are prone to any number of other forms of counterproductive thinking and behavior, you and your colleagues can expect to be working on identifying and overcoming these patterns as part of doing your job well. Together, in meetings, one-on-one sessions, and just during the course of your everyday work, you will also be seeking to get to the root causes of these patterns and continually devising different ways of doing things and seeing what happens as a result.

In a DDO, the root causes almost always are about people’s interior lives—about unwarranted and unexamined assumptions and habitual ways of behaving. And no executive or leader (no matter how senior) is immune from the same analytic process. When it comes to ongoing development, rank doesn’t have its usual privileges.

In the ordinary organization, every person is doing a second job no one is paying them to perform—covering their weaknesses and inadequacies, managing others’ good impression of them, and preserving a position that would feel more precarious if people didn’t always see them at their best. In a DDO, this is considered the single biggest waste of resources in organizational life.

Imagine if you worked in a place where your inadequacies were presumed not to be shameful but were instead potential assets for continuing growth, where business challenges were new opportunities to test out whether you could take a more effective approach to solving a problem, where no matter how effective you were at your job, you could keep stretching yourself to even greater levels of capability.

Imagine if you worked in a place where the definition of a “good fit” between the person and the job is “she does not yet have all the necessary capabilities to perform the role at a high level, but we will help her to develop them, and when she does she will have outgrown this job, and we will need to find her another.”

An implication of our work for companies that aspire to be high-performing cultures is summed up in this question: Would you continue to consign the development of your people (and, inevitably, only a fraction of your people) to one-off training programs, executive coaches, high-potential programs, and the like if you could make your organization’s very operations the curriculum and your company the most compelling possible classroom in your sector?

Being part of such an organization is not always easy, but the environment created by a focus on development in the workplace that is universal (across all ranks and functions in the organization) and continuous (and therefore habitual) unleashes some surprising qualities: compassion alongside tough-minded introspection and organizational solidarity that comes from collective work at self-improvement. This creates a different kind of vitality at work: a work and life integrated rather than balanced against each other.

With thanks to our research team members, Matt Miller and Inna Markus, who contributed to this piece and to the forthcoming HBR article, “Making Business Personal” (April 2014).

Culture That Drives Performance

An HBR Insight Center

Mindful Culture Through Simple Exercises

Employees Perform Better When They Can Control Their Space

Motivating People to Perform at Their Peak

Employees Who Feel Love Perform Better

January 21, 2014

Strengthen Your Strategic Thinking Muscles

Have you been told that you need to be more strategic? Whether through 360 feedback or after a failed promotion attempt, being told that you aren’t strategic enough really stings. Worse is when you try to clarify what “more strategic” would look like and get few tangible suggestions.

Being more strategic doesn’t mean making decisions that affect the whole organization or allocating scarce budget dollars. It requires only that you put the smallest decision in the context of the organization’s broader goals. Nurturing a relationship, such as one that could provide unique insight into a supplier, a customer, or a competitor is highly strategic. Everyone has an opportunity to think more strategically.

If you’re not being seen as enough of a strategic thinker, my guess is that it’s because you’re so busy. What percentage of your workweek is spent in meetings? How much of the time left over is a mad dash to respond to emails, make phone calls, and do some actual work? Is there anything left? Under the guise of productivity, you have probably squeezed out thinking time. The result is decisions that are based more on reflex than on reflection. The risk of reflexive, knee-jerk decisions is that they tend to be based on what has worked before. That would be fine if our world was static, but it is not. Your industry, your competitors, your customers are changing at an unprecedented rate. Doing what you’ve always done can be as risky (or more risky) as trying a new and unproven approach.

In this context, it’s critically important to make time to reflect before making decisions. What is involved? Who is involved? What is at stake? What is the opportunity and what are the risks? What at first seems like an opportunity might reveal significant risk and what seemed risky at first might reveal a significant opportunity.

Your other response to your harried life might be to make a list of things to accomplish, put your head down and get things done. But focusing too narrowly restricts your chance to be strategic. Strategic people create connections between ideas, plans, and people that others fail to see.

A senior banking executive was looking for a new IT vendor for operations in the Caribbean when he learned that another department was working on new customer service standards. His default reaction was to just carry on. But that would have been a lost opportunity to marry the system requirements with the new service standards, which allowed the marriage of better protocols for customer interactions with more efficient and effective data available in real time.

And remember, relationships are strategic too. The executive asked the new IT vendor to introduce him to other clients who had already implemented their new systems. He had the chance to ask questions about the vendor and how to optimize the contract and the relationship.

Strategic people see the world as a web of interconnected ideas and people and they find opportunities to advance their interests at those connection points.

But a person who reflects on situations and connects ideas and people still has one problem: it isn’t possible to do everything! Possibilities are unlimited; time, money, and resources are not. That necessitates the ability and willingness to make choices. In famous Renaissance group research, failure to focus on a few key strategies contributed to the failure to execute strategy.

Making choices, both about what you will do and what you won’t, it is a critical part of being strategic. Closing one door in favor of another requires the courage to take action (for which you could later be blamed) and confidence to abandon an alternative (which could be a missed opportunity). It is at the point of choice that your ability to be strategic is finally tested. It isn’t without risks, but the risk of not choosing, of spreading limited resources over too many options is greater.

You will be seen as more strategic if you take action and course-correct than if you choose to stagnate and doing nothing or stall from trying to do everything.

You don’t need a new title, more control, or bigger budgets to be more strategic; you just need to be more deliberate in your thoughts and actions. By investing time and energy to reflect on the situations and decisions that face you; by finding ways to connect ideas and people that you had never linked before; and by having the courage to make choices about what you will do and what you won’t, you will greatly increase your strategic contribution. Soon people will be looking at you differently, calling on you more often, and maybe even giving you that promotion you’ve been hoping for.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers