Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1484

January 16, 2014

Salman Khan on the Online Learning Revolution

The founder of the Khan Academy talks with HBR senior editor Alison Beard. For more, read the Life’s Work section in the January-February issue of HBR.

Why Can’t We Stop Working?

I hadn’t seen Jim in two years. When we reconnected recently, I was shocked. The handsome, dapper professional I knew had gained 30 pounds and started smoking. Bursting with nervous energy, he told me about his business travails — work so busy he was staying regularly until 10 at night, and a billionaire client sapping his energy and causing him grief. But the project with the billionaire would soon be over, he declared. “That’s great!” I said. “So you won’t have to deal with him again.” Well, Jim allowed, there might be another contract with him in the works.

It wasn’t about money. We were standing in the middle of his vacation home, enjoying prime mountain views. Business was booming; he only wished it were possible to spend more time up here at his dream home, and perhaps to start dating and meet someone. But, of course, it was possible. For some reason, he was choosing not to — and Jim’s not the only one.

As Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen described in his mega-bestseller How Will You Measure Your Life? (with Karen Dillon and James Allworth), the ROI of work is immediately apparent. You get instant feedback and, oftentimes, instant gratification in the form of raises, promotions, new contracts, or general approbation. The arc of family life is different. In the moment, it can be banal, boring, or discouraging.

Harvard happiness researcher Daniel Gilbert has shown that children don’t increase parents’ short-term happiness; in fact, on a day-to-day basis, parents prefer almost anything (from watching television to exercising) to spending time with their kids. Work is certainly one societally sanctioned excuse. Yet, says Christensen, many professionals are dismayed to wake up in midlife and discover frayed relationships, divorces, and alienation from their family. We have to grasp the difference between the short and long-term rewards of work and our personal lives.

Another challenge, says Shawn Achor, author of The Happiness Advantage, is that we misunderstand the relationship between happiness and success. We assume that professional triumph comes first: I’ll be happy when I make SVP! I’ll be happy when I get into the right graduate school! I’ll be happy when I make the 40 Under 40 list! But that’s actually backward. Instead, he writes, “Happiness is…the precursor to greater success. Every single relationship, business and educational outcome improves when the brain is positive first.” In other words, success is a result of happiness, not the other way around. And yet, so many executives work tirelessly, questing for a goal — happiness — that doesn’t come from professional achievement.

For many top performers, the idea of dialing back on work is also disturbing because they fear it will torpedo their career. Partly, of course, this anxiety is exaggerated. Since humans fear loss more than they covet gain, it’s easy to frame any deceleration as the loss of our career potential and a potentially disastrous mistake. But to complicate matters, in some particularly competitive fields like investment banking or corporate law, long hours truly are mandatory. And, culturally, we’re regaled with examples like Tesla’s Elon Musk, a twice-divorced father of five who took one vacation during a four-year period.

Even when it’s not all about us, the pressure to keep working full-tilt can be intense. As one successful consultant friend told me, “There are a lot of people that depend on me — the people who report to me, the people I mentor, and my clients. It’s very hard to turn away from them and let them down.” Indeed, when he recently cut back his travel schedule due to several family health crises, he got significant pushback from his colleagues. “I get emails and phone calls every day: we missed you at the meeting.” Grappling with divided loyalties can be challenging. “It hurts because some of them can sound scolding,” he says, “but I have to stick to my plan.”

Even when we know working to excess isn’t good for us, it’s hard to cut back. Most of us aren’t as extreme as the investment bank intern who died in London after allegedly working 72 hours straight to impress his bosses. But according to Christensen, we may not be that different, either: it’s a matter of degree, and timing. Overwork may not kill us tomorrow, but — if left unaddressed — it may kill our most important relationships in 10 or 20 years.

How do we strike a balance, particularly when work itself can be so gratifying? (My consultant friend says his intense schedule is the result of his desire to “make a difference in people’s lives, and I am good at it. That is very hard to give up and it keeps a lot of people happy.”) True success means recognizing our real, individual priorities and, as best we can, living them out today instead of pinning our hopes on some mythical future state of “I’ll be happy when…”

Three Ways Leaders Can Listen with More Empathy

Study after study has shown that listening is critical to leadership effectiveness. So, why are so few leaders good at it?

Too often, leaders seek to take command, direct conversations, talk too much, or worry about what they will say next in defense or rebuttal. Additionally, leaders can react quickly, get distracted during a conversation, or fail to make the time to listen to others. Finally, leaders can be ineffective at listening if they are competitive, if they multitask such as reading emails or text messages, or if they let their egos get in the way of listening to what others have to say.

Instead, leaders need to start by really caring about what other people have to say about an issue. Research also shows that active listening, combined with empathy or trying to understand others’ perspectives and points of view is the most effective form of listening. Henry Ford once said that if there is any great secret of success in life, it lies in the ability to put oneself in another person’s place and to see things from his or her point of view –as well as from one’s own.

Research has linked several notable behavior sets with empathic listening. The first behavior set involves recognizing all verbal and nonverbal cues, including tone, facial expressions, and other body language. In short, leaders receive information by all senses and not just hearing. Sensitive leaders pay attention to what others are not saying and probe a bit deeper. They also understand how others are feeling and acknowledge those feelings. Sample phrases include the following: Thank you for sharing how you feel about this situation, it is important to understand where everyone is coming from on the issue; Would you share a bit more on your thoughts on this situation; You seem excited (happy, upset…) about this situation, and I would like to hear more about your perspective.

The second set of empathic listening behaviors is processing, which includes the behaviors we most commonly associate with listening. It involves understanding the meaning of the messages and keeping track of the points of the conversation. Leaders who are effective at processing assure others that they are remembering what others say, summarize points of agreement and disagreement, and capture global themes and key messages from the conversation. Sample phrases might include the following: Here are a couple of key points that I heard from this meeting; here are our points of agreement and disagreement; here are a few more pieces of information we should gather; here are some suggested next steps—what do you think?

The third set of behaviors, responding, involves assuring others that listening has occurred and encouraging communication to continue. Leaders who are effective responders give appropriate replies through verbal acknowledgements, deep and clarifying questioning, or paraphrasing. Important non-verbal behaviors include facial expressions, eye contact, and body language. Other effective responses might include head nods, full engagement in the conversation, and the use of acknowledging phrases such as ‘That is a great point.’

Overall, it is important for leaders to recognize the multidimensionality of empathetic listening and engage in all forms of behaviors. Among its benefits, empathic listening builds trust and respect, enables people to reveal their emotions–including tensions, facilitates openness of information sharing, and creates an environment that encourages collaborative problem-solving.

Beyond exhibiting the behaviors associated with empathetic listening, follow-up is an important step to ensure that others understand that true listening has occurred. This assurance may come in the form of incorporating feedback and making changes, following through on promises made in meetings, summarizing the meeting through notes, or if the leader is not incorporating the feedback, explaining why he or she made other decisions. In short, the leader can find many ways to demonstrate that he or she has heard the messages.

The ability and willingness to listen with empathy is often what sets a leader apart. Hearing words is not adequate; the leader truly needs to work at understanding the position and perspective of the others involved in the conversation. In a recent interview, Paul Bennett, Chief Creative Officer at IDEO, advises leaders to listen more and ask the right question. Bennett shared that “for most of my twenties I assumed that the world was more interested in me than I was in it, so I spent most of my time talking, usually in a quite uninformed way, about whatever I thought, rushing to be clever, thinking about what I was going to say to someone rather than listening to what they were saying to me.”

Slowing down, engaging with others rather than endlessly debating, taking the time to hear and learn from others, and asking brilliant questions are ultimately the keys to success.

Employees Perform Better When They Can Control Their Space

If you want to build a culture of high performance, start by taking a look at your office environment. It matters more than you may realize.

As co-CEO of the design and architectural firm Gensler, I’ve spent my career designing workplaces and studying the link between design and business performance. Our firm’s four decades of collective experience and research indicate that an optimal physical environment can serve as a foundation for an effective workforce.

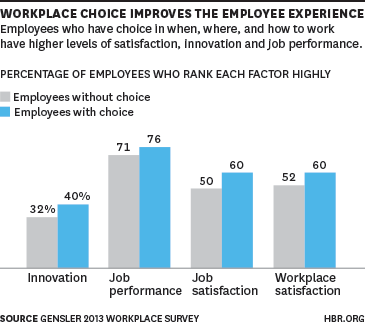

We wanted to take a deeper look at some of the more abstract aspects of workplace design that can impact employee performance. An emerging suite of literature and research—including our 2013 Workplace Survey — clearly points to the power of choice and autonomy to drive not only employee happiness, but also motivation and performance. We found that knowledge workers whose companies allow them to help decide when, where, and how they work were more likely to be satisfied with their jobs, performed better, and viewed their company as more innovative than competitors that didn’t offer such choices.

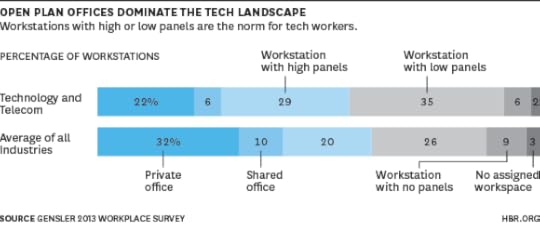

Take the technology workers in our survey, for example. Even though tech workspaces are more likely to be open-plan, a design that’s often seen as a distracting productivity-killer, tech workers in our survey reported an above-average ability to focus.

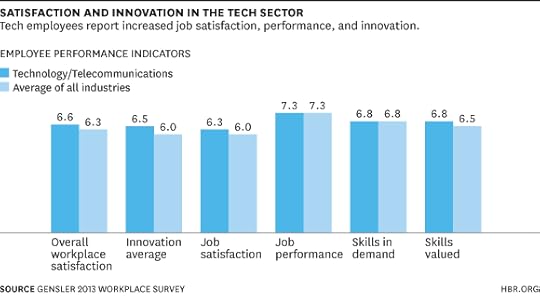

Our research also found that tech employees are also happier and more satisfied in their jobs and with their workplaces, than average.

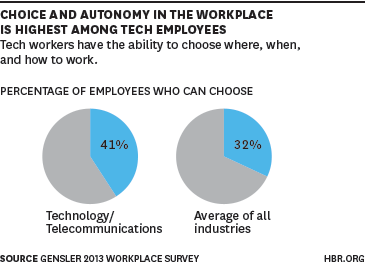

Why are they so satisfied? Choice was a key differentiator: Forty-one percent of the technology employee respondents reported having a say in when and where they work — which includes both in- and out-of-office mobility — compared to only 32 percent on average.

Facebook is a prime example. At their headquarters, employees have the ability to tailor the layout, height, and configuration of their own desks based on personal preference. Teams can also create whatever workspace layout best supports their project, moving desks into a circular break-out space or a long row of desks, for example. There are also vast arrays of meeting spaces across the campus available to all employees. And Facebook offers a range of options to employees for managing their personal lives and time, ranging from the transactional (banks, cleaners) to the social (restaurants, arcades) and those that lie somewhere in between (woodshop, studio). This additional layer of choice may not seem immediately work-related, but the ability to create and control one’s entire day as the needs of work dictate puts employees squarely in control of their own time management, productivity and processes. This has been shown to lead to greater organizational productivity and suggests that meeting an employee’s need for autonomy can influence motivation and performance.

Not every company can offer choice to employees on the same scale. But all organizations should carefully consider what they can do to give employees the spaces and tools that enhance and support their workday tasks as well as corporate goals. Choice is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Rather, it’s specific to the organization and its needs.

The recent Yahoo! recall seems to indicate that the organization’s remote work policy was no longer a type of choice that supported Marissa Mayer’s stated goal of enhancing innovation. Instead, she wanted a shared workplace that would encourage face-to-face interaction, idea sharing, serendipitous interactions, and informal meetings. A work environment with few assigned desks, cafés, lounge-style seating areas, and plenty of relaxed gathering spaces both inside and outside an office are just some of the physical design solutions that support innovation, while still offering choice.

At the global commercial real estate services firm CBRE’s new office in Los Angeles, there are no assigned offices or workspaces; instead, employees can choose from 15 different space typologies based on their activities and needs each day (from collaboration rooms, to comfy couches, to acoustically-treated, single-person glass enclaves.) To encourage this mobility and flexibility, CBRE provided employees with work-from-anywhere mobile technology and created a paperless office environment by digitizing almost all paper files. The firm literally and figuratively brought the walls down to encourage collaboration across divisions, increase productivity, and enable their employees to work in a whole new way.

Workplace choice is just one part of a broader culture of autonomy. With the support of organizational policy, and the right alignment of tools and technology to optimize productivity, it allows workers to optimize their own job performance, leaving them more satisfied, motivated, and creative – exactly the sort of employees you need to deliver high performance.

Culture That Drives Performance

An HBR Insight Center

Moving to a Safety Culture in Mining

Motivating People to Perform at Their Peak

Employees Who Feel Love Perform Better

Creating a Culture of Unconditional Love

Don’t Let Regulation Make Your Business a Rube Goldberg Machine

I love Rube Goldberg Machines, those inefficient systems, full of convoluted twists and turns that use chain reactions to complete simple tasks.

In one of my favorite examples, a tipped milk bottle releases a sword, which cuts a rope that drops a guillotine, which releases a battering ram to swing a door that wields a grass sickle while disturbing a hawk, who drops a boot that stomps on the head of an octopus, whose tentacles squeeze an orange to produce a single glass of freshly squeezed orange juice. These cartoons can give us a good laugh, but to model a business in this gratuitously complicated way would be akin to planning to fail.

Efficient, uniform operations are table stakes in the modern business environment. We rely on carefully crafted systems, policies, and procedures to reduce the cost of doing business and ensure a consistent experience for customers.

Having perfectly designed and executed operations is an impossible goal, but it is one we must continue to strive for. The barbarians of entropy are ever at the gate.

So while no one would set out to emulate Rube Goldberg’s creations while designing business systems, as regulations and industry standards have changed, complicated twists and turns enter our operations anyway.

It’s hard enough to keep operations efficient inside a company, but new regulations can present special challenges. As new constraints are introduced, systems are adapted to allow the business to continue functioning. At some point, a firm needs to decide whether respond to new regulations piecemeal, without considering how each small change may impact the larger system over time, or whether it’s time to implement a systemic overhaul to maintain operational integrity. While such overhauls can be daunting, the proactive route can pay off.

The long-term benefits of investment in system overhaul may not seem obvious, especially with federal environmental legislation proving elusive in recent years. When you don’t know what the rules are going to be, doesn’t it make sense to hold off on pushing through any major changes? In fact, the reverse is true: with more laws being enacted at the state and local level, the greater the operational complexity they introduce when your approach is a reactive one. Even as federal efforts like a national Cap and Trade program have stalled, for instance, states and cities are introducing new rules of their own: four states are currently implementing organic waste diversion programs and Los Angeles has just implemented a plastic bag ban. Regional legislative differences like these can wreak havoc on a firm’s systems.

I see this firsthand in my work dealing with waste hauling and recycling programs in the retail grocery industry. When a state or municipality enacts legislation that requires the diversion of specific materials from the waste sent to landfills, it typically impacts a small portion of a firm’s locations. The leaders in charge of that region naturally look for the simplest operational exception that will satisfy the regulatory requirement, but may not consider the big picture impacts of the changes. The solution might be idiosyncratic and inefficient, but it’s accepted as a cost of doing business.

Thus the first twist is added to the machine.

Before long, a neighboring city gets wind of the program and enacts similar legislation. Different operating groups deploy a variety of exceptions as new regulations are deployed with differing requirements, and local service providers may be unable to provide preferred solutions, forcing additional exceptions into a firm’s systems. The answers are suboptimal, but viewed at the level of the problems they seem acceptable and inevitable.

Soon, more twists and turns are folded in to the company’s operations.

Depending on the size and scope of your business, you may face a continual stream of new regulations. After a few years, your operations may start to resemble OK Go’s music video for the song “This Too Shall Pass,” which starts with the seemingly innocuous pushing of a model car into a stack of dominoes. From there the chain reaction winds through a wildly diverse array of actions which culminate with the band members being sprayed by paint cannons.

Here’s the problem with such operational complexity: It took two months of planning by a group of engineers, a team of thirty volunteers, and over sixty attempts to get OK Go’s music video manifestation of a Rube Goldberg Machine to run successfully. At the end of the video, the volunteers cheer loudly as the band is successfully blasted with paint. If we were directors rather than managers, maybe we could call in volunteers to contribute the time and labor to paper over our operational inefficiencies, but that’s not the case. We rarely get a second chance to get something right, let alone sixty chances — let alone a cheer when it all goes according to plan.

By reacting to regulatory changes one by one, rather than holistically integrating sustainable business practices, organizations incur losses where opportunities for gains exist. Tackling these changes independently may make sense in a vacuum, but as they accumulate you’ll quickly reach a tipping point at which continuing to create additional exceptions is not a wise business decision. When you find yourself at this crossroads, a systems thinking approach can help reframe the exceptions and provide perspective from which a better path appears.

When regulations start piling up, take a look at the constraints collectively. Many of them will likely be similar, but there may be others that are more stringent. Once you understand the limitations, you can start brainstorming solutions that will satisfy requirements across the entire firm. Done properly, you might even give yourself a bit of headroom to obviate the need to respond to subsequent legislation. When you’re able to implement systems that are ahead of regulatory requirements, your team will be able to focus on operating the business.

Where I have seen the destructive effect of the reactionary approach, I have also quite clearly seen untapped opportunity. Implementing an integrated sustainability program often allows businesses to turn costs in to revenues, while reducing related risks. By staying ahead of the curve, you’ll track regulatory changes to ensure you’re already in compliance, rather than having to alter your business in response to each new piece of legislation, keeping operations streamlined and uniform.

If you stick with the reactive approach, however, you will eventually make a gauntlet out of processes that otherwise could be simple and straightforward.

A real Rube Goldberg Machine might only be run once before it’s dismantled, as it takes a great deal of effort to set it up and tune it for a successful run. That’s the magic of it: in building the machine you are taking part in a flight of fancy. Businesses, however, cannot thrive on the basis of such whimsy.

Fortunately, leaders who opt for the proactive approach can stay ahead of the game.

Imagine that the next time a harried colleague asks you, “How are we going to deal with this new rule?” you can respond that you are aware of the upcoming changes, and that your operations already exceed the new requirements. Wouldn’t that be nice?

To Detect a Lie, Don’t Think About It

Research participants who did puzzles for 3 minutes after hearing a series of true and false statements were about 6 times better than other people at figuring out which of the statements had been lies, according to a team led by Marc-André Reinhard of the University of Mannheim in Germany. The finding suggests that unconscious thinking (like the kind you do when you’re working a puzzle) gives people a chance to integrate the rich, complex information needed for accurate lie detection, and it supports a theory that deception judgments are largely driven by intuitions that may be inaccessible to the conscious mind, the researchers say.

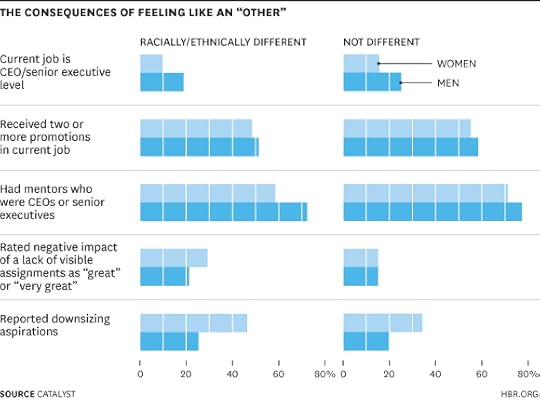

Minority Women Report Downsizing Their Ambitions Because of Bias

It should be simple: Go to work, work hard, get noticed, and get promoted. But is it ever really that straightforward?

New research from Catalyst reveals that women who identify as racially or ethnically different from the majority of their coworkers:

Are less likely to be at a company’s C-suite or senior executive levels

Receive fewer promotions

Are less likely to have high-level mentors — and may therefore be less often recommended for important opportunities

Feel more limited by a lack of access to high-visibility assignment

Are more likely to downsize their aspirations.

This feeling of being racially/ethnically different is not only detrimental to these women; it is also a tremendous loss to companies, which are potentially missing out on a wealth of top talent.

So why is this happening? Our research has shown that women who feel racially or ethnically different may not be reaching the higher echelons of organizations because they’re inadvertently disadvantaged by common talent selection practices. Advancement is predicted by access to “hot jobs”—assignments that increase an employee’s chances of being promoted by providing greater visibility, important decision-making opportunities, and the opportunity to develop global skills. Some hot jobs involve international assignments, responsibility for managing a budget, and/or line responsibilities.

One proven way to access these jobs is through sponsorship, which is when a senior person at your company advocates for you and recommends you for crucial assignments. The higher his or her rank, the more clout a sponsor has, and the better positioned that person is to help you succeed.

The problem is that most companies’ upper echelons are still dominated by white men. Catalyst research demonstrates that, among those who have themselves been sponsored, high-ranking men are far less likely than high-ranking women to sponsor junior women — and less likely to sponsor junior women than to sponsor junior men. Because they lack sponsors with clout, women’s chances of being given hot jobs are slim, and they are more likely to be overlooked for promotions that could help them climb the corporate ladder.

This is not because men don’t want women to succeed. Rather, it’s due to the unconscious tendency most people have to favor those who are most like themselves. This leads to a process called “homosocial reproduction,” wherein existing power structures are maintained when those in power choose to surround themselves with others who look like them. The more you differ from those in power, the less likely you are to benefit from this phenomenon.

Being a woman in a white man’s world is hard, and being a man of color in a white man’s world is hard. But being a woman of color in a white man’s world is even harder.

These combined effects may be responsible for the limitations women with additional “other” statuses report experiencing. Fortunately, smart companies can act now to make sure all employees are given a chance to succeed. Catalyst recommends:

Putting mechanisms in place, such as diverse selection and promotion committees, to ensure that those with backgrounds different from a workgroup’s majority members are evaluated fairly, based on their performance and potential.

Encouraging senior executives to sponsor colleagues whose identities differ from their own.

Holding managers accountable for ensuring that all high-potentials have equal access to career-accelerating jobs by tracking who gets access to these opportunities and who, if anyone, does not.

Equipping people managers to become inclusive leaders, developing and honing a repertoire of behaviors, explored in a forthcoming Catalyst report, that will make them more effective at leveraging the talents of all employees—not just those with whom they share the most in common.

It’s worth noting that there are many reasons other than race/ethnicity and gender why an employee might feel self-conscious or excluded. Your company may have employees who are working in a country other than their country of origin or LGBTQ employees. The experience of “otherness” is broader than any one demographic category, and it’s important to consider whether there may be employees in your company who feel excluded due to a non-visible characteristic.

True inclusion may seem like a difficult challenge, but it’s really an exciting opportunity. The best way to maximize a team’s effectiveness and help a company harness the power of all employees’ skills and talents is to ensure that everyone feels comfortable and included at work — and fully valued for what they bring to the table.

January 15, 2014

Research: Using a Smartphone After 9 pm Leaves Workers Disengaged

Smartphones are enormously valuable for helping people to fit work activity into times and places outside of the office. Now that workers are able to access email and websites at any time from almost any location, they can be responsive to professional demands in ways unimaginable just a few decades ago. Customer-centric organizations can remain attentive to customers’ needs around the clock. Time-critical events can be addressed quickly. People can leave their offices without fear of being disconnected from their work. Indeed, many would consider smartphones to be among the most important tools ever invented when it comes to increasing the productivity of knowledge work.

However, our new research indicates the greater connectivity comes at a cost: using a smartphone to cram more work into a given evening results in less work done the next day. The reason for this, as we’ll explain, is that smartphones are bad for sleep, and sleep is very important to effectiveness as an employee.

That a well-rested employee is a better employee is well established by research. To note just a few recent studies, insufficient sleep has been linked to more unethical behavior at work, cyberloafing, and work injuries, and less organizational citizenship behavior.

Unfortunately, smartphones are almost perfectly designed to disrupt sleep. Because they keep us mentally engaged with work late into the evening, they make it harder to psychologically detach from the most pressing cares of the day so that we can relax and fall asleep. More generally they encourage poor sleep hygiene, a set of behaviors that make it harder to both fall asleep and stay asleep. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of smartphones to avoid is that they expose us to light, including blue light. Even small amounts of blue light inhibit the sleep-promoting chemical melatonin, meaning that the displays of smartphones are capable of producing this effect.

Thus, as researchers, we had good reason to suspect that using smartphones at night would yield negative effects at work the next day. Specifically, we hypothesized that a greater number of minutes spent using smartphones after 9pm would more negatively affect sleep; that this in turn would leave people feeling tired in the morning; and that, as a result, they would be less engaged at work the next day. In other words, using smartphones to squeeze in a bit more work at night would lead to lower engagement at work the next day at work, through lost sleep as a causal mechanism. To test that hypothesis, we conducted a pair of studies. (These studies will be published in detail in the research journal Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes later this year.)

In our first study, we had 82 mid- to high-level managers complete multiple surveys per day for two weeks. This entailed “within persons” analysis, meaning we compared each individual’s daily data only to that person’s own data on other days. This allowed us to examine daily effects, unclouded by individual differences. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that late-night smartphone usage cut into sleep and made people tired in the morning, and that, as a result, they were less engaged at work the next day.

In our second study, we had 161 employees from a broad variety of occupations (both managers and non-managers) complete the same set of surveys, with the addition of measures of late-night usage of television, laptop computers, and tablets. The harmful effects of smartphones on sleep and work engagement held even after accounting for these other electronic devices. Indeed, out of all those devices, smartphones were associated with the most powerful effects.

Our study adds to a pile of scientific evidence that managers must begin to acknowledge in their work. There are downsides to having employees use smartphones – direct ones for the employees, and less direct but still troubling ones for workplaces. Smart managers will look for creative ways to minimize the problems without giving up the mutual benefits of smartphones.

One solution suggested by Harvard Professor Leslie Perlow, based on her research on high-end consultants, is to have predictable time off. And the best way to start is by agreeing that evenings and normal sleeping hours are the most important times for people to be predictably “off.” This will allow employees to psychologically disengage from work and minimize exposure to the blue light produced by electronic display screens.

Another potential solution calls for creating new norms as to when employees are expected to respond to work email and when they are not. Leaders should be sensitive to how their personal behaviors shape norms; employees will not feel pressure to check their mail late in the evening if their bosses aren’t using that time to send messages. A handy tool is to set a delivery delay on email such that it arrives the next morning. With this approach, managers who are traveling or working odd hours can still communicate at their convenience, but minimize the negative effects on others.

As smartphones become more embedded in our daily lives, we should continue to seek solutions that will enable us to stay in touch with smartphones and still get the sleep we need to be effective the next day. In contrast to a short-term perspective that puts the current work item as the top priority, a perspective that focuses on longer-term performance will leave more room for managing smartphones in a manner that preserves sleep. The more important the job, the more important it is to work with a fresh brain. We would do well to remember that, and not let our phones call the shots.

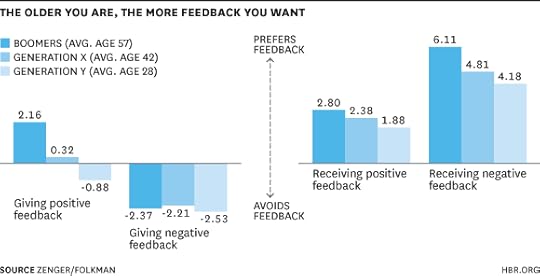

Your Employees Want the Negative Feedback You Hate to Give

Would you rather hear positive feedback about your performance or suggestions for improvement?

For the last two weeks, we’ve been compiling data on this question, and on people’s general attitudes toward feedback, both positive and corrective. So far we’ve collected it from 899 individuals, 49% from the U.S. and the remainder from abroad. Before we tell you what we found, we suggest you take the same assessement here so you can put our findings within your own personal context.

What our assessment measures is the extent to which you prefer to give and to receive both positive and corrective feedback. It also measures your level of self-confidence. For the purposes of this study, we grouped praise, reinforcement, and congratulatory comments together as positive feedback. And we’ve chosen to call suggestions for improvement, explorations of new and better ways to do things, or pointing out something that was done in a less that optimal way corrective feedback. We think this is an important distinction, because as the following data affirm, people want corrective feedback, as we’ve defined it, even more than praise, if it’s provided in a constructive manner. By roughly a three to one margin, they believe it does even more to improve their performance than positive feedback.

The graph below shows, on average, the degree to which the participants in our initial sample tend to avoid or prefer giving and receiving positive and corrective feedback.

The first column indicates that roughly the same number of people prefer to give positive feedback as those who do not. This is fascinating, given the high percentage of people who appreciate receiving positive feedback, along with its positive impact on performance improvement.

The second column shows how much people prefer to avoid giving negative feedback (a finding that came as no surprise to us, certainly). The third column shows that people prefer receiving positive comments to the same degree that they dislike giving negative feedback. Again hardly a surprise.

We also asked respondents an additional question: Would they prefer praise/recognition or corrective feedback? And this time their replies did surprise us. A significantly larger number (57%) preferred corrective feedback; only 43% preferred praise/recognition. Well, perhaps that’s not surprising, since our most emphatic finding related to which kind of feedback had the most impact on people’s job performance. When asked what was most helpful in their career, fully 72% said they thought their performance would improve if their managers would provide corrective feedback.

But how it was done really mattered — 92% of the respondents agreed with the assertion, “Negative (redirecting) feedback, if delivered appropriately, is effective at improving performance.” In this regard we find it telling that the people who find it difficult and stressful to deliver negative feedback also were significantly less willing to receive it themselves. On the other hand, those who rated their managers as highly effective at providing them with honest, straightforward feedback tended to score significantly higher on their preference for receiving corrective feedback. And, as the graph below shows, there also appears to be a strong positive correlation between a person’s level confidence and his or her preference for receiving negative feedback.

We were curious to see if people of different generations felt differently about feedback. In our sample 12% were Baby Boomers, 50% were members of Generation X, and 38% were in Generation Y. As our final graph shows, everyone displayed an aversion to giving negative feedback (though interestingly, the Gen Xers slightly less so). And every group was both open to positive feedback and even more open to corrective feedback.

But generally speaking, the older they were, the more feedback people wanted of both kinds. The Boomers, in fact, showed a much stronger preference for giving positive feedback and for receiving negative feedback than the other two groups (while the young Gen Yers don’t seem to feel comfortable giving even positive feedback yet.) Some people have hypothesized that the members of Gen Y are hungry for and open to feedback, and especially to positive feedback, but here it turns out their preference is not as strong as the Boomer and Gen X groups. It’s not clear whether these differences are primarily age related or a function of having been in the workforce for a shorter period of time.

What is clear is the paradox our data reveal, no matter how we slice them. People believe constructive criticism is essential to their career development. They want it from their leaders. But their leaders often don’t feel comfortable offering it up. From this we conclude that the ability to give corrective feedback constructively is one of the critical keys to leadership, an essential skill to boost your team’s performance that could set you apart.

Stop Trying to Predict Which New Products Will Succeed

When is it possible to predict a product’s success? How you answer this question may be the most important factor in how you design your product development process — and, ultimately, in whether your business succeeds or fails.

Is market performance predictable for a specific product or class of products? If so, we should use a set of processes when designing and launching businesses that are geared for prediction — ask the right questions, perform the right analyses, plan production and supply chain for predictable variations on projected sales. And, if prediction falls outside of an acceptable range, we should hold our teams accountable for predicting poorly.

In contrast, when performance cannot be predicted, a process geared for prediction makes no sense. Outcomes will usually be much worse than predicted, and we will waste design, production, and distribution resources. Worse still, we will punish employees even if they do everything right, and create incentives to avoid unpredictable products, even though these products are essential for growth. And products that are more successful than predicted can be even worse: we’re unable to deliver to customers, both losing potential revenue and compromising our reputation for other products as well.

For products that cannot be predicted, we should focus on recognition — on trying to identify as quickly and cheaply as possible whether a product is succeeding when it’s actually introduced in the market, and create production and distribution processes that are flexible enough to adapt to our recognition of success or failure. In this case, accountability is not for correct ex-ante prediction, but for fast learning and contingent execution.

Fundamentally, these are two different ways of doing business — processes that excel in one context fail miserably in the other — so the crux is trying to identify when prediction is possible. To do that, we must first understand how prediction works.

Though there are multiple types of prediction, the gold standard is the prediction of precise outcomes. Such predictions provide both magnitude and time horizon (or at least one of the two); finance tools like the CAPM and Black-Scholes formulas give us partially-specified predictions — value without time; Newtonian physics gives us a “law”, fully-specified predictive theory, completely deterministic and accurate for the directly observable world.

In the context of a new product, only this type of precise prediction yields enough information for us to plan on. In order for us to plan for a product launch, we need to know the sales and the time horizon — without both, our production and distribution schedules will go hopelessly awry.

The question is whether our ability to predict the success of new products reaches this threshold of precision. An easy way to begin addressing the problem is to examine the accuracy of your projections. One study, of an industrial conglomerate, found that estimates of cost-saving initiatives, line extensions, and new products had average accuracy of of 1.1, 0.6 and 0.1, respectively, suggesting that market risk is the major driver of our inability to predict.

Look at the variance of your new-market products. If you’re typically off by an order of magnitude but using processes that assume accuracy, scrap your current process and recreate it assuming unpredictability. First recognize if the product is solving a real problem and people will buy it, then figure out how to scale production and distribution in situations of success.

We have a set of processes created for recognizing success in inherently unpredictable projects — lean product development, customer discovery, discovery-driven planning — yet we consistently fail to apply them. As a result, our predictions for new products are either too high or too low, and we waste resources, customer goodwill, and employee motivation.

Rather than merely hoping our predictions will be better next time, we must accept that we can’t predict new product success, and refocus on recognizing as quickly as possible whether a newly introduced product is working.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers