Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1467

February 18, 2014

Make Your Career a Success by Your Own Measure

As a manager, how can you cultivate a sense of career growth and development for your people, even when possibilities for promotion are limited or nonexistent? I posed this question to my human resource management students recently. (The context was that we’d just been considering some evidence that “Gen Y” employees are likely to head for the doors if they don’t see short-term prospects for career advancement.) While my students generated several promising ideas, some advocated an approach that dismayed me: Companies should increase the layers of management, they argued, to provide for more frequent promotions.

Of course I understood why they might think so, but this was a “be careful what you wish for” moment. Anyone old enough to have worked in the many-layered organizational structure of the past knows its shortcomings.

But what bothered me most about their idea was the reminder of how many of us feel lost without external signposts to mark our success. Particularly for young people, it is a tough transition to leave the familiar and clear markers of school success behind and learn to thrive on the more ambiguous ones that mark a lifetime of employment. Crafting a truly successful career demands a high level of self-awareness and ability to self-direct, capacities that schools and universities don’t always do a great job of developing.

As an example, let me introduce you to Sam. Sam grew up in a close-knit family in a US community with excellent schools. His father is a sales manager, his mother a pediatrician. Always a top student, Sam did well as an accounting major in the honors program of his state’s excellent flagship public university, graduated and took a job with a financial services firm. That is where his story took a more somber turn. He struggled with the work and found the corporate culture alienating. Used to outperforming his peers, Sam was shocked at his first performance review when his boss informed him that his performance ratings were unacceptably low. He had six months to improve.

Having always understood the rules and done well playing by them, Sam felt adrift for the first time in his life. Rather than wait for the ax to fall in a job that made him increasingly miserable, he quit after four months with no idea what to do next and moved back home. Although only marginally interested in a legal career, he submitted law-school applications in order to quell his parents’ anxious daily questioning about his career direction as well as the invasive thought that he was a fraud and a loser. At least, he told himself, I know how to be a good student.

Employees of any age can suffer from a similarly constrained career perspective. I recently coached Thomas, an employee in his late thirties, who was thrown into crisis when he discovered that his new boss hadn’t nominated him for the company’s high-potential program. He found it difficult to focus on anything else. A broader view of career success would be helpful to Thomas, as it would be to Sam and to the students in my classroom discussion. It would enable them to tap into a wider repertoire of responses and gain more learning and insight from their experiences.

People do not advance in the broader arenas of career and life by taking linear steps and acing assignments that are carefully constructed to allow them to prove mastery. They do it by navigating the unpredictable events and conditions that both work and non-work life throw at them — and responding and adapting in the ways that make sense for them. If you’re dependent on external markers to judge whether your career is successful, you will find them, but only in some realms and on certain dimensions of achievement. If you only pay attention to only this limited set of success indicators, you are less likely to experience your career as successful. Imagine going to a sumptuous buffet dinner, but only tasting the salad. It won’t be satisfying.

Visible, objectively measurable achievements such as sales results, salary, bonuses, and promotions are forms of career success that we tend to fixate on—sometimes to the point that we overlook other aspects that are just as valuable to us. It’s important to consider both objective and subjective markers of success. The perceptions and feelings we have about our work experiences and what we achieve affect us as much as the extrinsic rewards do. Consider the fact that there are plenty of people who look successful, who hold high-level positions and earn impressive salaries, yet who feel unfulfilled in their careers.

Be mindful, too, that a piece of work can prove “successful” through individual experience and through interaction with other people. You can feel success when you accomplish your own goals as an individual, when you develop greater understanding of a problem and perceive a solution, or when you express your identity or your values through your work. You can taste success in interpersonal settings, when for example you develop an excellent mutual understanding and rapport with a supervisor or mentor, or help other people to grow, or have a positive impact through your work on the organization or its external customers. Research shows that such subjective and relational experiences contribute enormously to assessments of career success.

Finally, if the promotions and raises a boss can dole out are the only forms of career success you recognize, then at times when there are no higher-level openings to move into, or when budget cuts prevent salary freezes, you have set yourself up to become demoralized. Being able to think broadly about career success and to identify your successes for yourself is essential to resilience.

With this in mind, I encourage you to take a few minutes now to reexamine your own work experiences, and identify successes you might have overlooked. Not earning as much as you’d like? Perhaps you’ve gained creativity by working with highly talented colleagues. Concerned that it’s been several years since your last promotion? Don’t negate the value of your having grown into a recognized subject-matter expert in a strategically valuable area for your firm.

To stimulate your thinking, here are some additional indicators that may help you recognize your own career success more fully, or help you identify pathways toward greater success:

Performing work that you find interesting and fascinating

Overcoming challenges

Having autonomy in how you perform your work

Developing new skills and deepening existing ones

Having work and personal life complement and enrich each other

Doing work that gives you new insights into yourself, your organization or your industry

Being recognized as an expert

Having the trust of your colleagues and superiors

Building valuable relationships inside and outside of your organization

Contributing to shared knowledge in your organization by training others

Enjoying career stability and employment security

Collaborating effectively with a team of talented colleagues

Receiving recognition for your achievements and contributions

Seeing the positive impact of your work on end users or on society

Leaving a legacy that you’re proud of

Now consider: as nice as external markers and affirmations are to get, would you really rather have them than any of the above? Yes, you deserve both. But keep in mind that careers are long, and that it’s rare to experience all forms of career success simultaneously.

You need to develop the awareness and adaptability to notice, appreciate, and exploit opportunities to enjoy career success in all its different forms, even if the most explicit, generic forms of recognition aren’t currently available. With practice and attention, you can reap your own harvest from a wide variety of work experiences, and as a result, enjoy a richer and more satisfying career.

Walk Your Way to More Effective Leadership

In 1978, my wife, Ginger, and I began daily 30- to 60-minute walks in our neighborhood in a weight-control effort. We found that we enjoy this activity together. It is the time when we talk about a full range of topics: family issues, financial discussions, career decisions, information exchange, and even neighborhood gossip.

Walking has become an important part of our lives, enriching us physically, mentally, spiritually and professionally. With Ginger often with me, I have walked in almost every major city in the United States and numerous smaller ones in the course of my everyday activities over the past 36 years. I have walked in some 45 countries in North America, Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Walking has definite health benefits not only for weight control but also for improving diabetes, reducing high blood pressure, possibly delaying the development of Alzheimer’s disease and other positive outcomes. But I have also used my daily walks as a tool for communication and leadership, including team building.

For example, in 1989, when I was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to serve as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), most of the agency heads and staff in HHS knew little, if anything, about me, because this was my first appointment to a position in the federal government. So during my initial meetings with HHS staff, I invited them to join me on my morning walks in Washington and in the 10 cities around the country where we have our regional HHS offices. This proved to be very popular: Between 10 to 150 people showed up to walk in Denver, San Francisco, New York and elsewhere. During my walk in Dallas, one excited HHS employee informed me that I was the first HHS secretary he had met and talked with during his 23-year tenure in the department.

During these walks I learned a lot about the history of the department, ongoing policy debates and current departmental morale. And my staff learned a lot about me: my history, my goals for my tenure as HHS secretary, my value system, my communications skills, and my hobbies. Most important was the bonding that resulted between me and the leaders and staff of the department. We became an effective team.

In September 1990 when I released Healthy People 2000 — a guide to enable Americans to improve health behavior and strengthen prevention activities by the year 2000 — I decided to use the occasion to illustrate the many benefits of walking. I invited the public to join me for a walk through Washington, D.C.’s Rock Creek Park. More than 300 people turned out for this event.

Daily walking has added to my knowledge and enjoyment of cities, countries, landscapes, and scenes of everyday life around the world. I have found that early morning treks not only give me a head start on my day but also afford an opportunity to see and enjoy sights and sounds I wouldn’t otherwise experience.

A few years later, I served as chair of Medical Education for South African Blacks (MESAB) — a nonprofit organization formed to help alleviate the shortage of black doctors, nurses, and other health professionals in that country. MESAB’s scholarships also facilitated the enrollment of blacks in universities, thereby accelerating the dismantling of apartheid. On my visits, I often invited South African members of the MESAB board to join me for my morning walk. These excursions proved invaluable for discussions of our operations there. This simple activity enhanced our communications and effectiveness.

The benefits of walking can go beyond personal health, enjoyment, and communications. One such example is an event I organized in 1989: an annual 5-K run/walk on Martha’s Vineyard. Each August, the proceeds from our sponsorships help to support the island’s only (and very important) hospital.

For me, walking has proved to be a great way to promote a healthy lifestyle, while facilitating my communications skills and leadership efforts. My life has been and continues to be enhanced by this activity, which is readily available to almost all of us.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Executives’ Biggest Productivity Challenges, Solved

A Successful International Assignment Depends on These Factors

How an Olympic Gold Medalist Learned to Perform Under Pressure

Tackle Conflicts with Conversation

The Comcast-Time Warner Merger Is Not a Sign of Strength

The announcement late last week of Comcast’s $45 billion merger with Time Warner Cable set off a predictable frenzy of hyperventilating by much of the technology media and self-appointed consumer advocacy groups. The deal, we heard, would be a “disaster for consumers,” and “bad for America.” It would create a “bully in the schoolyard” who could “cement the kind of monolithic monopolies that have plagued cable subscribers all along” and lead to a long-feared “media dystopia.”

But when the smoke clears and the details of the transaction become clear, the merger will reveal itself to be a much simpler affair, one that is much more defensive than it is strategic.

No Harm to Competition

For one thing, thanks to a long history of exclusive municipal franchising regulations that didn’t end until 1992, the two companies don’t overlap in any market—TWC customers will become Comcast customers (and get arguably better technology and service in the process), but no local market will see a decline in the number of competitors.

The combined entity will control thirty percent of total U.S. cable subscriptions, or about 25% of all U.S. homes, nothing close to a monopoly in the legal or any other sense of the word. Still, the deal will receive close scrutiny from both the FCC and antitrust regulators, and could take up to a year to approve. But rejecting it will be hard to justify under current law.

What Industry is Consolidating?

Looking at the merger in terms of continued consolidation within the cable industry, however, misses the bigger picture. There is no cable industry. Cable is just a technology, increasingly one of many, for transmitting information, whether video, voice or data.

Where cable was once the only technology used to distribute television programming—a vast improvement in speed, quality, and quantity over antennas—it now competes with fiber, copper, satellite, and mobile broadband, each with their own pluses and minuses, and each promoted by companies large and small, who together continue to spend heavily to upgrade their assets. (According to the FCC, broadband access providers across technologies have invested over $40 billion a year in capital improvements every year since 1996.)

As formerly siloed content has converged on the all-digital Internet protocols, each of these technologies is now communicating the same bits, often in hybrid networks created to provide for optimized responses to consumers’ insatiable demands for more content in more forms on more devices. Cable systems offer WiFi for mobile access; mobile networks rely on cable, fiber, and even copper for backhaul.

A Tidal Wave of Content

Beyond creating new kinds of competition, the convergence of technologies and content types has put the longstanding and often highly-regulated business practices of all infrastructure providers into an existential crisis as content creators proliferate and rapidly find new markets. That’s because the digital revolution has now made it possible to develop, produce, and distribute information in regular waves of better and cheaper technologies—the pre-conditions for what Paul Nunes and I have called “Big Bang Disruption.”

Today, a hundred hours of new video is uploaded every minute to YouTube alone, much of it from individual producers using technologies that would have cost a fortune only a few years ago. Add in Vimeo and other Internet-based platforms, and crowdsourced funding from companies such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo, and anyone can now create, broadcast, and monetize their own channel. Many of us do.

At the high end, Netflix, HBO, iTunes, and Hulu each have millions of customers. Along with Amazon and other Internet giants, many of these distributors are beginning to produce their own original content. Netflix, which already has far more customers than the post-merger Comcast, just released a new season of its self-produced and Emmy-winning series “House of Cards.” As many as 15% of all Netflix customers watched it on the first day.

This is a true golden age for consumers, who are demanding innovation in both the packaging and pricing of content. Different segments want different channels bundled, others subscription-based, and still others advertiser-supported. We’ve just begun sorting out the new business arrangements for a tidal wave of new content.

No Sign of Strength

Mergers and acquisitions among traditional infrastructure providers is not a sign of their growing power, in other words, but of increased pressure on their traditional business models, another sure sign of Big Bang disruption in process. The multi-front digital onslaught will inevitably generate more consolidation among incumbents, and ultimately the emergence of a new industry structure.

As weaker competitors fail to adapt, the remaining incumbents are likely to increase their market share, as for example when Circuit City and other electronics retailers closed in response to new competition from Amazon and other better and cheaper Internet retailers. Best Buy looked to be a winner, but the real story was about the growing dominance of digital commerce, which continues to squeeze the shrinking number of big box stores.

Likewise, the actual driver of accelerating consolidation among technology and media companies is the growing leverage of content providers large and small.

The average cable subscriber’s monthly bill, for example, includes $5 the operators must pay Disney just for ESPN, whether they want it or not. Beyond ESPN, Disney owns, well, pretty much everything.

Among newer companies, Netflix has already dispatched physical video giants such as Blockbuster. Now, its growing subscriber base and its original programming has changed the equation in negotiations over access to every form of distribution infrastructure.

Last year, for example, the company introduced new high-definition streaming, but only for access providers who meet the requirements of its “Open Connect” program, which requires on-site installation of equipment that gives priority to Netflix traffic.

That’s the sense in which Comcast’s merger with TWC is largely defensive. Since 2005, cable companies have lost ten million subscribers, many to satellite and others to cord-cutters who get all their content from the Internet. So in addition to the obvious economies of scale the larger entity can achieve, a bigger Comcast may have improved bargaining power in negotiations with fast-growing content providers. Some of those rending their garments over the deal argue a bigger Comcast will use the merger to get better prices for its customers for premium programming, an odd argument for consumer advocates to make.

Miles to Go

Beyond consolidation, Comcast, along with other media incumbents, must find new ways to innovate products and services. That was clearly the incentive behind the 2011 acquisition of NBC Universal, which gave the company access to a massive library of old and new content.

Indeed, those who fear that Comcast’s merger with TWC will upset the balance of power in the dynamic and rapidly-evolving information industry can take solace in both the process and outcome of the more strategic NBC Universal deal. Regulators took over a year to approve that transaction, and along the way extracted over thirty pages of legally-binding concessions and conditions, many of them unrelated under the most generous reading.

These include protections for producers offering programming for minority communities, low-cost Internet access for low-income homes, and a commitment by Comcast to abide by the FCC’s “Open Internet” rules despite the fact that a federal court last month threw most of them out as wildly exceeding the agency’s legal authority. (Those commitments will now extend to TWC’s customers and markets.)

No doubt the advocacy groups, as well as Comcast’s many competitors in the emerging information ecosystem, are drawing up Christmas lists of new conditions even now. Many of them will probably make the final cut when the transaction closes, whenever that is. Hopefully, their unintended side effects won’t wind up making things worse for consumers.

Do Millennials Believe in Data Security?

Millennials have a reputation for being the most plugged-in generation in the workplace. Experts have even suggested “reverse mentoring” so that younger workers can inculcate their “tech-savvy” habits in older generations. But a new survey from Softchoice shows that those may actually be bad habits when it comes to keeping data secure.

For instance, 28.5% of twenty-somethings keep their passwords in plain sight, compared with just 10.8% of Baby Boomers. They’re also significantly more likely to store work passwords on a shared drive or word document that isn’t itself password-protected, and more likely than older workers to forget their passwords.

And it gets worse! They’re more likely to email work documents to their personal accounts, move documents via cloud apps that IT doesn’t know they have, and lose devices that would give whoever found them unrestricted access to company data. Basically, in every way that Softchoice measured, the youngest workers were the most likely to lose data or leave themselves open to hacking.

But – here’s the kicker — they’re also the most informed about the risks. Younger workers were also the most likely to say that their company has a clear policy on the downloading of cloud apps; that their IT departments have communicated about the risks of cloud apps; and that their workplace has a clear policy on how to protect information.

So what’s going on?

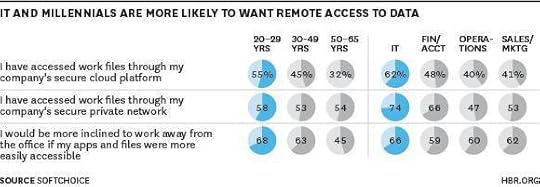

In part, it’s just that this generation’s well-documented impatience. Which, as an older Millennial myself, I would rebrand as “efficiency.” We just see a bigger payoff in having the data we need when we need it. For instance, the primary reason Millennials cited for not seeking company approval before downloading a new cloud app was that the IT department simply takes too long.

The same logic drives their emailing of sensitive documents to themselves – more than other generations, they said they had to transfer work files to their personal computers, otherwise they couldn’t access the information they needed from home. And unlike older generations, twenty-somethings are more willing to work from home as long as they have the data they need to do so. This goes back to what young entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley call “the merge” – rather than juggling “work” and “life,” the two fuse into a seamless whole. And our tech habits follow suit: we’re much more likely to use the same apps for both work and personal reasons.

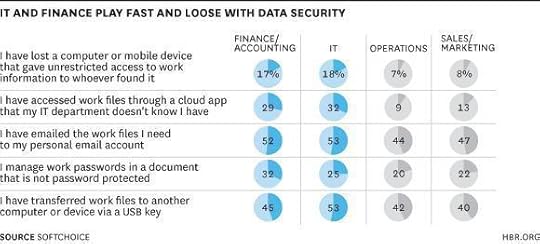

But there’s something else happening here, too — and it shows up in some of the other segments in the Softchoice survey. Workers (regardless of age) who use cloud-based apps are also less rigorous about keeping company data safe than those who don’t. And sorted by function, IT itself is among the worst offenders in violating their own data-security protocols, neck and neck with Finance:

Taken together, these patterns suggest that the people who use write down their passwords, email documents to themselves, and store company documents in the cloud are those who simply use technology the most — and the ones who need or want to access their work from multiple locations. (A different survey, which ranked employees by level of seniority as opposed to age, found that senior leaders were worse than lower-ranking managers when it came to data security. I’m willing to bet it’s the same logic; the more you work away from the office, the more likely you are to violate your IT department’s policy–and justify the increased risk to company data by your own increased productivity).

And it’s not in this survey, but I suspect Millennials and IT workers just have a different take on the ROI of spending time on data security. When major data breaches and password hacks are announced regularly by major corporations, when the NSA is listening in on your phone calls, when Julian Assange and Edward Snowden are leaking secret government documents, and when absolutely everyone, from your dentist to your hairdresser, asks for your Social Security number – does it really matter if your password is taped to your screen?

Or do you just assume that if the hackers want to get you, they will?

Note: the Softchoice survey also measured workers over the age of 65 and HR professionals, but the sample sizes for those segments were quite small so I’ve excluded those data sets here.

When You’re Preparing for a Task, Say “You Can Do It,” not “I Can Do It”

People who referred to themselves as “you” or by their own names while silently talking to themselves in preparation for a five-minute speech were subsequently calmer and more confident and performed better on the talk than people who had referred to themselves as “I” or “me” (3.6 versus 3.2 on a combined five-point scale, in the view of judges), says a team led by Ethan Kross of the University of Michigan. The research participants who talked to themselves in the second or third person also felt less shame afterward. By distancing us from ourselves, the use of the second and third person in internal monologues enables us to better regulate our emotions, the researchers say.

Keep Your Kids Out of the Entitlement Trap

Want to know what keeps the owners of the most successful family businesses up at night? The dread that their kids will grow up to be entitled.

This is the concern of most parents, but among the very wealthy, the anxiety can be sometimes paralyzing: Will their children and grandchildren end up lazy, good-for-nothings, who are not contributing to society? In other words, “trust fund babies,” the kind whose scandalous antics fill the pages of the New York Post.

That’s not paranoia; the fear is grounded in reality. In business families, it’s quite common for the next generation to grow up in a much wealthier environment than the current generation. The problem is not limited to them. A study of over 3,000 families found that when wealth is passed from one generation to the next, a whopping 70% of it is squandered. Speaking generally, wealth is a very difficult thing to manage well.

That said, in reality, money turns out to be a less important factor than one might think in the development of entitlement. Some very rich kids turn out to be highly motivated and engaged – we see this in our work every day. Our experience also suggests, however, that kids don’t mysteriously end up entitled; there are some common choices parents – all parents – make to a greater or lesser degree that substantially increase the odds that kids end up feeling that the world owes them a living. These choices are often made with the best of intentions, but they work against the long-term interest of our children.

How do you avoid the entitlement trap? There are no pat answers. What we learned from our work with family businesses is that you can start by asking yourselves questions. This is not a scientific formula, but the more “no” answers that are scored, the greater the likelihood that you are putting your children on the path to entitlement:

Do they hold down jobs? Kids that have jobs – even part-time or volunteer jobs – are more successful, both personally and professionally, than those who don’t. In an informal study of what people shared who made it to the C-Suite, one major American bank singled out height and summer jobs. There’s not much you can do about height, but work brings enormous discipline and learning. Jobs are also tremendously grounding, psychologically: they keep kids from being bored, one of life’s great vices. What we also see with glaring clarity in our work is that parents are blind to the strengths and vulnerabilities of their children. It’s hard to be objective. Jobs give your child the chance not only to gain experience, but als0 to get honest feedback. Reality is one of the best ways to combat a false sense of entitlement.

Can they build careers? Sometimes the next generation just can’t get traction, and they’re not entirely to blame. Alarmingly, in about a quarter of the client situations we work in, we see adult children being set up to fail. Owners sometimes give members of the next generation hopeless assignments – for example, they are asked to turn around a losing business that has no chance of becoming profitable. Typically, this is done out of a desire to have the adult children understand, even relive, the experiences of the parents, who have almost always had to overcome tremendous challenges in order to succeed. The same thing can happen outside a family business, when adult children are forced into careers and professions in which they have no interest, and often no talent. Not surprisingly, they often don’t do well. Paradoxically, too much disappointment can also lead to entitlement. When even our best efforts are not good enough, it often seems better to just sit back and wait for life to be delivered to us on a silver platter.

Are they allowed to suffer? Life is like the stock market: it’s up and down, and there is risk involved. Don’t set your kids up to fail, but don’t shelter them from fate’s hard knocks. Let your children feel the pain – it builds resilience. Indeed, research shows increasingly that resilience flourishes in an environment of tough love. But don’t make your kids suffer too much either. The best way we’ve seen wealthy family business owners help out their grown children without creating a sense of entitlement has been to provide assistance with education and housing. The owners of a very successful family business we work with hold back dividends but have a large educational fund that pays everyone’s schooling. They also help out with “reasonable” housing costs. After that, everything else is the adult child’s responsibility. This discipline wonderfully concentrates everyone’s mind on the vital difference between wants and needs, and nips entitlement in the bud.

Are they grateful? Recent studies show that there’s an inverse relation between materialism and gratitude. This poses obvious challenges for families that enjoy great wealth. In her pioneering work on the subject, British psychoanalyst Melanie Klein wrote that, without gratitude, there can never be any personal satisfaction; envy creeps in and desecrates everything. We all have something to be envious about, even the very rich – sometimes especially the very rich – but envy is a toxic emotion. Gratitude can soften it, and Klein thought that gratitude was inborn. But new findings on gratitude show that it can also be taught. The key is that parents must model gratitude before kids can develop it. That takes work. Practice gratitude yourselves, and chances are that your children will end up thanking you for it. That’s the first step out of the entitlement trap.

Much more can be said on many fronts, and we look forward to your comments on this issue. But one last word: in our experience, the way that the most successful business families curb the next generation’s sense of entitlement is by staying involved in their kids’ lives. If they fail to get some quality time, your children turn to money as the next best substitute. That sounds trivial, trite, perhaps even a platitude. But every child is entitled to love. The rest is gravy.

February 17, 2014

Why One Executive Quit Business Travel Cold Turkey

If you’d like to have an in-person meeting with venture capitalist Brad Feld, there’s only one place where you can do it: Boulder, Colorado. Last year Feld, who is managing director at Foundry Group and co-founder of TechStars, announced he would no longer travel for business. He equipped his Boulder offices with state-of-the-art video conferencing systems, and now holds meetings using this technology or asks business partners to travel to see him. Feld, who recently wrote about this decision in Inc. Magazine, told HBR why he went cold turkey. Excerpts:

How much did you used to travel?

For the past 20 years, I’ve traveled for business between 50% and 75% of the time. There have been long stretches where I’d leave on Monday and return on Thursday or Friday. I didn’t just go to one place — I’d often go to two or three cities during the week. My wife Amy started referring to what she got on the weekends as “the dregs.”

What made you decide to make a change?

In 2012, I finally broke. I had a bike accident at the beginning of September but ignored the fact that I was badly beaten up. I traveled non-stop in September and October. By November, I was feeling depressed and then ended up in the hospital for surgery to remove a kidney stone. I recuperated in December and hit the road in January to attend CES. Within two hours of getting to Las Vegas I wanted to hide in my room. Over the first half of 2013, I struggled through a deep depressive episode – my third as an adult. As I sorted through things, I made a bunch of tactical changes and reflected on where I was at age 47. One thing I realized was that I had completely lost all the joy in business travel, and I had no interest in doing it anymore.

What, specifically, was it about the travel that was causing you distress? Was the hassle/physical wear-and-tear the bigger issue, or was it mostly the intrapersonal strain of being away from home?

It was the cumulative effect of many miles on the road. The physical impact was real: I had deluded myself into thinking that I had ways to manage it. For example, I’m a very good sleeper on planes so I’d generally just nap from wheels up to wheels down, even on longer flights. I used these naps to justify only sleeping five hours a night on the road, but this took a toll, because the sleep on a plane was low-quality sleep. I always missed my wife Amy, but it had shifted from a “I miss you / I love you / I’ll see you soon” kind of thing to a deep sense of sadness that I was spending so much of my time away from her. The combination of the physical and emotional costs finally did me in.

Did you try or consider tactics short of a complete travel ban — such as doing only day trips, taking private planes to reduce the hassle, or bringing family along?

I’ve tried everything. Amy is a writer so she’s traveled with me plenty, but if I’m trying to blend work and being with her, in some ways that gets even more exhausting. And I’d never subject her to my three-cities-in-three-days routine. The day trip thing doesn’t really work well from Denver — you can’t pull it off on the east coast and while I’ve done it plenty of times to the west coast, it makes for a very long day. Given my travel intensity, private never really was sustainably economic and the periodic private flights were nice, but in that “well — this is nice — but whatever” kind of way that didn’t really change the fact that I wasn’t home.

Was there anything you enjoyed about business travel that you miss now?

Nope. Nothing. Zero. I didn’t travel for the last half of 2013 and decided not to travel in 2014 for business. I’ll travel for pleasure, to see a friend, to spend the weekend with my dad, or to go on a vacation with Amy. But no business travel. I’ve always had a hard time doing things in moderation, so for me it’s usually all or nothing — so I decided to completely abstain from business travel.

There’s an old line that you “can’t fax a handshake.” How much are you losing by videoconferencing with people instead of meeting directly?

I still meet with a lot of people — they come to Boulder, which has the happy coincidence of being both centrally located in the US and a wonderful place to come visit. I think anything I’m losing by “not being in the mix with masses of people” is being gained through deeper thought on the things I’m working on.

As a VC, you need to conduct due diligence on companies. Isn’t this better done in-person, when you can see the headquarters, feel the office vibe, or meet employees spontaneously?

Not really. At the very early stage that I invest in, the personal relationship with the founders matters a lot, but I don’t care whether they are working out of a shed behind their house or the corner of a co-working space. So I do spend a lot of time with the founders — either in Boulder or via videoconference — and that works for me.

A lot of middle or senior managers could never dream of eliminating travel altogether — they aren’t their own bosses and don’t have total control of their work lives. Short of that, how can they work to systematically reduce travel?

I think a lot of people default into traveling. I know I have for many years. The costs to the individual, and to the company, often far outweigh the benefits. As technology continues to evolve, there are more high-quality remote options for work and collaboration (in addition to standard video conferencing), I think it benefits all organizations — large and small — to aggressively explore these. While there will always be value in being face to face, the need — or requirement — of it is overrated. In many cases, it’s just a rationalization for getting away from home, or the office, doing something different, or being heroic by physically transporting yourself all over the place.

Thriving at the Top

An HBR Insight Center

Executives’ Biggest Productivity Challenges, Solved

A Successful International Assignment Depends on These Factors

How an Olympic Gold Medalist Learned to Perform Under Pressure

Tackle Conflicts with Conversation

The Other Factor that Makes an Idea Spread

How do ideas spread? Previous research has focused on what happens to the sharers of an idea: what emotions they feel, what types of content inspire them to share (practical, funny, “sticky” and so on). And it is true that from memetics to mirror neurons to social contagion, it is likely that for any given idea, multiple factors are involved. And yet the role of content seems to get all of the focus. There are scores of books written about how to make your content “go viral” or “become contagious” and take on a life of its own. We seem to overlook — or at least undervalue — the role of the person delivering the idea: the carrier.

But over two years of research we’ve been conducting using TEDx as a case study, what has emerged is the importance of idea carriers. In addition to attending TEDx events in 24 different countries, we created a survey that was shared by TEDx organizers with thousands of participants in over 50 countries. (Disclosure: many years ago I founded TEDxEast, and remain loosely involved with the organization now.) What we found was that much of the desire to share an idea with others was linked to that idea’s carrier. It’s the carrier who gets the audience to open up, trust, and ultimately spread the idea.

An important distinction: the carrier is the person who brings the idea into the common vernacular, although they may not actually be the one who discovered or researched the idea. They may be impeccable storytellers, thinkers, or writers. They make fresh connections and present cogent arguments. They are critical in getting ideas to take hold.

Some well-known examples of carriers of ideas would include Daniel Goleman, who popularized the idea of emotional intelligence in 1995 although the concepts and research were actually conducted by John Mayer and Peter Salovey. Malcolm Gladwell has brought forth the ideas of others in nearly all his books from Blink to The Tipping Point and Outliers. Maria Popova of the popular blog Brainpickings connects different theories and opinions in unexpected ways. What is it about these carriers that gives them the gift of spreading ideas? Part of it is the storytelling, of course. But there are other factors here as well.

People want to like the carrier. When people feel good, they want to share – that good feeling is what they want to spread. As Jonah Berger writes in Contagious, “When we care, we share.” While most previous research has examined content that makes people feel good — whether it is a heartwarming video about motherhood or a silly caption plastered over a photo of a cat — carriers who connect with their audiences have the gift of making whatever idea they’re discussing palatable.

People also want to see themselves in the idea. Jesse Preston and Daniel Wegner have done research on what they call the Eureka Error- where people misattribute credit for ideas based on mistaken effort. This can work in the favor of carriers — who often simply want to spread ideas, not get credit for inventing them — because audiences may feel that by sharing the idea with others, that somehow makes them a co-creator. They mentally give themselves credit where credit is not due. That’s not great for the actual originator of the idea, but it is great for the idea itself. For example, if I hear an idea for reducing poverty from Bill Gates and then share it with others, I get a proxy sense of construction/creation. Bill Gates is unlikely to care that he — or the original researcher who came up with the idea– is not getting credit, as long as poverty reduction is getting more attention.

The people who dismiss the work of idea carriers as “nothing new” are missing the point. There are many examples of ideas that have taken off not because they were new or novel but because they were finally discussed in such a way as to make them more compelling to audiences. As Dr. William Duggan of Columbia Business School notes in his book Strategic Intuition: The Creative Spark in Human Achievement, all ideas stand on the shoulders of those that have come before. Idea carriers create space for ideas in the popular imagination. They connect ideas to the larger intellectual landscape and give them context they may lack standing alone. Carriers like Gladwell, Goleman, and Popova do this expertly for us, as do less household-name carriers through their extensive and influential social networks.

When people like an idea carrier and the carrier shows them how to see themselves in the idea, people are much more likely to share that idea with others. This is powerful information for speakers who want to authentically build a bridge to an audience to create this experience. It also raises questions of who may best introduce an idea–the researcher who uncovers the idea or someone who serves as a carrier.

“All the forces in the world are not so powerful as an idea whose time has come,” goes the famous line by Victor Hugo. A skilled carrier can bring ideas into their time that much more quickly.

Russia’s Business Future Lies With the Boys (and Girls) in Batman T-Shirts

The Sochi Olympics have focused the world’s attention on Russia’s ability to get things done. Or inability — in the leadup to the games, almost all the attention was on the massive cost of the games and the fact that lots of journalists were staying in troubled hotels (with weird toilets). Things have turned more positive since the opening ceremonies, but there are still lots of questions about how prepared Russia really is to compete and thrive in the global economy.

Those questions led me to Pekka Viljakainen, a veteran Finnish tech entrepreneur and executive who has spent the last two years advising the Skolkovo Foundation, founded in 2010 by current prime minister (and former president) Dmitry Medvedev to promote tech entrepreneurship in Russia. Viljakainen is also author of the management book No Fear: Business Leadership in the Age of Digital Cowboys — and of the 2012 HBR.org post “What the Heck Is Wrong With My Leadership?“ I asked him what he’d learned about Russia’s capabilities, and in particular its managers and entrepreneurs, over the past two years. In return I got repeated invitations to attend Skolkovo’s “Woodstock of startups” June 2 and 3 in Moscow (you’re all invited too, apparently), and the answers below (which have been edited for length and flow).

So … what have you learned?

Pekka Viljakainen: Just to give you a very practical thing, I’m going to visit 28 cities in Russia this spring, meeting 400 to 2,000 people per city, young talents. And they’ll have Batman T-shirts on, they don’t give a shit about the politics, they just want to do business.

This is something that is totally untapped potential. Within five or 10 years, the old ex-Soviet people will be gone from the power elite. In the new government headed by Mr. Medvedev, I am an adviser and I am one of the oldest. I am 41. And the ministers are like 34, 35, 36 years old. I live four days a week in Moscow, and we never go even to have a beer after work. Not to mention vodka. People go to practice for a triathlon, they go to take care of their children, they go to watch the kindergarten Christmas parties, and so forth. This was not the case in Soviet times at all. The whole value base is totally changed.

But obviously the most visible guy outside the country, Putin, is still of that older generation and older style.

PV: Without a doubt. Russia is like 79 states of the U.S., and the difference between the states is much bigger than between Texas and Boston. There are 100 nationalities, lots of different languages. I don’t see it as a surprise that the traditional leadership culture is like a tsar. Because if an ultraliberal president would start tomorrow, we might see 50, 60, 70 wars — like in Bosnia in the ‘90s. In that sense I have started to understand a little bit what Mr. Putin does and what he doesn’t do.

But you’re absolutely right that that his age group is what I call the Soviet children. The big question mark both from the business opportunity standpoint but also from the risk exposure standpoint is how the new post-Soviet leadership generation is mentored and educated to be the new leaders of the country.

In terms of business leadership, at the risk of making sweeping generalizations, what’s different about it in Russia?

PV: If I take a 30-year-old leader at a startup or a big state company, I think the skill set and value base do not differ drastically from a guy in Stockholm or Boston or London or Silicon Valley. The differences in this basic toolkit of managers are surprisingly small. However, what is missing is that leadership is about models and best practices. In Russia, people don’t have in their mindset a leadership model for knowledge businesses. Because all the great leaders in Russia are either oil/gas, heavy industry, manufacturing, or construction.

The problem is not where to find the great engineers or great project managers. The problem is where to find leaders who can build powerful teams in knowledge-intensive businesses. That is the reason I was headhunted to Russia, because I have experience in this.

Russians are entrepreneurial by nature. When the Soviet Union collapsed all the equity was gone, currencies were gone, and they still had to survive so they had to be entrepreneurial. But the leadership issue is a problem.

If you think about the basic mentality in the U.S. or Silicon Valley everybody has been told, “Guys, start your own enterprise, even though it’s risky.” In Russia, mothers and fathers tell their kids, “Igor, you can start your business, but it’s not only risky, it’s dangerous. It’s almost lethal.” Because of the history.

Are there things about the Russian approach to business that work better than what you’ve been accustomed to?

PV: Russians are very pragmatic in solving problems — because they have been in a tough environment, so to say. Don’t take this literally, but the killer instinct in business, the killer instinct in a positive way, is strong. It’s a much more straightforward approach, and I think that’s a good thing.

In my team at Skolkovo Foundation, I have about 20 young talents. If I give them a task, they will find a solution. First they ask “Mr, Viljakainen, what should we do specifically?” I say “Hey, guys, have you read my No Fear book? If you still ask after one year working here what to do, whether I give you permission to do something, forget it.” After working two years together they are performing super well. I feel they are really good at executing tasks. They are extremely goal oriented, and really hard-working people.

There is one mega problem for the Soviet economy because of demographics. In the ‘90s not many children were born, because it was so uncertain with the fall of the Soviet Union. In all countries, people talk about needing more women in leadership, but in Russia it is practically nonexistent, women as leaders. This is a cultural issue; it’s a very masculine culture in many ways. But for the Russian economy, if there are no females in leadership, the whole economy will fail because there just aren’t enough leaders.

From what I have seen of Russian women as leaders, they’re extremely good. They’re much better at managing people, they don’t have the façades that men will have. I trust in the Russian women a lot to be able to lead knowledge businesses.

And now back to Sochi, and all those toilet problems.

PV: I was also in Beijing for the Olympics. If you have been in a place where 25 new hotels were built in Beijing, I don’t know how many toilet problems were reported, but I can tell you that not all of those hotels were high class from day one.

In Russia, a whole new city was built. I was there three years ago and there was absolutely nothing. Now there is a new airport, new railways, waste management up to European Union standards, 25 hotels. Everything has been built in three years, and I would be amazed if everything would be cool, so to say. Given the magnitude of the project, the fact that the construction business in Russia is the most heated and most corrupt of all, I think it’s a miracle that everything was in such a good shape as it was.

What is insane of course is, if it’s true, how much money was spent in corruption. Having said that, when you build a new city from scratch I would not count that the Olympics cost $50 billion. I would say that the Olympics was $10 billion, and then $40 billion was building this whole infrastructure. You might argue whether it makes sense or not, but Sochi is a wonderful place. Like Saint-Tropez, with a mountain behind it.

Three Decisions that Defined George Washington’s Leadership Legacy

A cynic might conclude that George Washington, the first president of the United States, owes his legacy to his towering physical stature and other superficial characteristics. The man looks like a leader, and perhaps that made him a convenient figurehead on which we hang idealized virtues. But the cynic would be mistaken. Here are three counter-intuitive decisions Washington made that show what an exceptional leader he truly was.

1. General Washington decided not to impose a battlefield strategy on his field commanders. The general consensus among historians is that Washington was a mediocre military strategist at best. However, a recent study in the Academy of Management Journal cast some doubt on that consensus.

The study found that in large, multifaceted enterprises, the biggest threat to speedy strategic decision making is “strategic imposition” from the mothership. Historians still debate whether Washington favored a “Fabian strategy” of quick attacks and even quicker retreats, or a more traditional strategy of fighting major head-to-head battles. The discrepancy comes largely from the fact that he imposed neither strategy. His young and mostly inexperienced commanders were free to employed either one. At a high level, Washington decided that the Colonies would always have a standing army in the field that was as well-trained as possible under the time and budget constraints, rather than a hodgepodge of untrained militia men roaming the countryside. Beyond that general strategic direction, and some basic tactical goals, Washington let his young leaders make their own strategic decisions in the field—capitalizing on the speed and agility advantage they had over their larger and better-trained competitors.

2. Washington decided to oversee renovations on Mount Vernon during the most tenuous year of the Revolution. Imagine leading a comically outnumbered, under-resourced, and woefully unskilled force where the majority of your teenaged army marches throughout the New England snow barefoot because you can’t afford to buy them shoes in a war that—if lost—could send you to the gallows for treason. Then in the midst of all this, staying up late at night sending letters home describing the right color of the new curtains in the living room. Historians are still puzzled as to why throughout 1776, Washington continued micromanaging his home renovations from the front lines of the most difficult, dangerous, chaotic, and important leadership position of his life. Perhaps the only thing more puzzling is how he maintained confidence and composure in spite of knowingly facing such overwhelming odds.

Modern psychology might provide a clue to this riddle. Psychologists at UCLA and NYU discovered that after making a benign decision such as where to go on vacation and then making a basic plan for executing that decision, people showed significantly higher self-esteem and optimism, while feeling less vulnerable to completely uncontrollable risks such as earthquakes. In other words, making even a small decision on something completely unrelated to your primary focus can shift you into a confident, empowered mindset.

One of Washington’s greatest assets during the American Revolution and his presidency afterward, was his ability to inspire the confidence and alignment needed to gather political and financial support from so many diverse stakeholder groups including the Continental Congress, the American public, the French government, and his own soldiers. Perhaps this peculiar, yet easily controlled side project was precisely what enabled Washington to stay in the confident, decisive mindset that his leadership role demanded.

3. Washington Decided not to make himself supreme ruler of the United States. After risking his life to lead the American Revolution—often bravely putting himself directly in the line of fire—Washington shocked the entire world by voluntarily returning all his powers to the American people and their elected representatives. It was a decision that even led his recently defeated foe, King George III, to comment that Washington was “the greatest character of his generation.” We will never know whether this decision was driven by altruism or a self-interested desire to be adored by history. What we do know is that decision aligned perfectly with the pattern of decisions Washington established throughout his lifetime. He was an exemplar of what Wharton professor Adam Grant describes as “otherish”—people who are both highly giving and highly self-interested.

Regardless of how pure Washington’s motives may or may not have been, it’s easy to imagine a bright future for a world populated by leaders who treated every decision as an opportunity to reveal the high quality of their character.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers