Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1347

October 30, 2014

Why Tim Cook’s Coming Out Matters for Apple, and Business

Ellen. Anderson Cooper. Michael Sam. All three broke barriers by coming out in their respective industries – comedy, television news, and football. Now they’re joined by Apple CEO Tim Cook, who just announced that he’s “proud to be gay” and, in the process, became the first Fortune 500 CEO to come out. Earlier this year, two CEOs of publicly traded – yet much smaller – firms came out. But until Tim Cook’s statement, “don’t ask, don’t tell” reigned at the highest echelons of corporate America – almost shocking in 2014, given that 91% of Fortune 500 firms prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

As Cook notes, Apple has long taken a corporate stand in support of LGBT rights and has spoken up against discriminatory laws. But his announcement gives new heft to their commitment. Cook’s sexuality was long an open secret; as he acknowledges, “For years, I’ve been open with many people about my sexual orientation. Plenty of colleagues at Apple know I’m gay, and it doesn’t seem to make a difference in the way they treat me.” But it creates a sort of cognitive dissonance when a company is advocating for equality, yet its leader remains publicly quiet about his own identity.

Cook’s new openness shows that Apple is walking its talk on diversity – positioning them even more favorably in the never-ending Silicon Valley talent wars. It’s also likely to make him a more effective CEO. As Sylvia Ann Hewlett and Karen Sumberg reported in the Harvard Business Review, despite fears to the contrary, being out in the workplace actually has significant advantages – notably, that workers can concentrate on excelling at their jobs, and not “managing” their identity. (And remember, there are still 29 states where it’s legal to fire someone because they are gay.)

Indeed, even for those like Tim Cook, who was out to colleagues but not to “the world” at large, the stress of downplaying one’s identity can take a toll. Research by the Deloitte University Leadership Center for Inclusion showed that 83% of gay employees “covered” at work – i.e., even if they were technically out, they still felt the need to minimize their differences by, for instance, not bringing their partner to work functions, or not displaying family photographs at the office. Cook’s coming out demonstrates powerfully to executives at Apple – and elsewhere in the corporate world – that covering is no longer required to succeed at the top.

“I consider being gay among the greatest gifts God has given me,” says Cook, because it’s increased his empathy toward others and helped him learn to follow his own path – an important asset in a company that prizes innovation and built its brand on the strength of breakthrough ideas such as the iPhone.

“We’ll continue to fight for our values,” he says, “and I believe that any CEO of this incredible company, regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation, would do the same.” That’s probably true, but it means a great deal for Apple, and the many companies who hope to emulate its success, that Cook is willing not just to speak up for equality in general, but also to stand up and be counted.

When Real-Time Intel Still Isn’t Fast Enough

We now live in a world where both man and machine can access data on almost any topic at any moment. Documentation of our world happens in real time, through a constant, autonomous torrent of ones and zeroes — and research and recall of that information have been reduced to mere mouse clicks. With all data available at all times, opportunities — and adversaries — can also move in real time. So we should ask ourselves, “How do we move faster?” This is the domain of predictive analytics — a concept that isn’t new, but the potential of which, in a world not limited by data or processing power, is expanding rapidly.

I’m at Lockheed Martin where we focus relentlessly on expanding and improving the technology and tradecraft to remain ahead of adversaries. Our investments in predictive analytics primarily serve the goal of anticipating threats emerging from dynamic environments, and being able to do so faster than others. (it would be naïve to think that our adversaries are not finding opposing uses for these technologies). From predicting the locations of roadside bombs to pinpointing the next government collapse, exploiting available data requires high-performance collection and rapid, thorough, and transparent analysis.

It is fascinating, however, that the solutions we’ve developed have also turned out to be effective in fighting other threats to safety and wellbeing – among them, criminal networks and bacterial infection.

Granted, the political and military turmoil right now in Syria and Iraq is a more typical focus of the analysts using something called LM Wisdom, the solution we developed to automate the collection of data and subject it to advanced processing and analysis. LM Wisdom is being used to monitor events in real-time, and correlate, aggregate, and index massive sets of multi-language data. By using processing steps and filters, analysts can collect information and integrate everything from locations to tonality of messages to modes by which people are communicating with one another. Once a model of what’s happening right now is created, correlation algorithms tailored to specific problem sets enable the prediction what might possibly happen next. Information processed through LM Wisdom augments traditional intelligence gathering, so decision makers can understand various threats and what they could rapidly become.

For over half a century, the aerospace and defense industry has been at the forefront of defining advanced analytic techniques, because we needed them to address highly complex engineering challenges. Some of these challenges are well known, such as propelling a man faster than the speed of sound and safely landing a man on the moon. Countless others may never fully be appreciated by the public at large. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of these early solutions was that they all relied on a multi-disciplinary approach, combining mathematics, engineering, computer science, and physical sciences.

What has become abundantly clear across the decades is that any application of analytics to a complex problem relies on three essential components. Analysts need to acquire meaningful and abundant data sets, often from multiple sources internal and external to the organization. Algorithms are then needed to weed out the noise from high-value information and “connect the dots” across the information. Lastly, analysts must rely on their tradecraft – the investigative skills required to ask the right questions of big data.

What is new, however, is that we are no longer limited by data or processing power. Data is enormous and available in real-time — we are now, as many have observed, in the era of Big Data. Processing power, meanwhile, is now so immense that we can capitalize on this abundance. It might seem that more data would increase the unlikelihood of finding the proverbial needle in the haystack, but this challenge is largely overcome by the sheer processing power available in modern computing platforms. The true value of expansive data is in the enablement of analytic prospecting — quickly identifying and recognizing patterns and connections within the data. We can look beyond finding the needle to finding patterns that might indicate the presence of a needle. We can truly start going faster than real-time.

Moreover, the same multi-disciplinary approach and computational ideas used to simulate airflows of fighter jets or predict missile trajectories can now be applied to harness data and unearth actionable intelligence in previously intractable areas. For example, we have employed data analytics to assist in the discovery and identification of criminal networks responsible for producing and distributing counterfeit drugs. Using essentially the same tools we use to make sense of political and military turmoil, we were able to discover the true identities and aliases of key players as well as the flow of money through the illicit network.

It turns out, too, that the same toolkit can be applied in medical settings. We found that the signals that human bodies constantly emit can be tracked just like a missile or satellite. For example, our team developed an algorithm that detects sepsis, a potentially fatal blood condition, in patients’ bloodstreams up to 14 hours faster than currently employed techniques. Our bodies give off signals like temperature, blood pressure and white cell count, and using these signals, the algorithm can help health care systems and providers deliver more personalized medicine with higher likelihood of improved outcomes.

The power and applications will only continue to grow and spread. Big data will only get bigger. The more computing devices we connect to the internet of things and the more areas to which we apply complex algorithms will only expand the information we have prior to making decisions. As data and processing power cease to be a limiting factor such analysis will revolutionize the way we interact with the world and measure the risks of our decisions.

Of course, these growing capabilities are also available to people who mean to cause us harm. Meeting the challenges that they will present will always be a matter of staying ahead. In a world not limited by data or processing power, real-time awareness will not be sufficient. We will need to be faster.

For more expert insights on the power of predictive analytics, see HBR’s Insight Center, Predictive Analytics in Practice.

Imagining Productivity Apps for the Apple Watch

App developers from Stockholm to San Francisco are anxiously counting down the days til the November release of the Apple Watch SDK (or “Software Development Kit”), which will give them the tools to begin building their own concepts.

I’d argue that these developers stand at a crossroads for the Internet of Things (IoT). Following one path, they can design the familiar types of apps that we already see on tablets and phones, simply scaled-down for a smaller screen. In doing so, they would treat the watch — and by default its wearer — as just another connected data-collecting “thing” among “things.”

Following an alternative path, developers would design for the humanity of the wearer, prioritizing individual intelligence over collective intelligence. For example, they would prioritize my needs (say to make a smart decision) over the data aggregator’s needs (desire to sell tailored ads, for instance), offering the user radically new insights and privacy safeguards — a non-negotiable trait for such an intimate device. On this path, developers would mine insights from cognitive science and UX about the distinctive ways body, brain, and things interact. People wouldn’t be seen as just another IoT node. Below, I describe some strategies and insights to get the conversation (and prototyping) started:

What the Apple Watch does that other connected things don’t do. Many analyst predictions and early use cases, including those from Apple, place watch apps in a continuous narrative; one in which software is adapted from one generation to the next. First there was email on your PC, then on your mobile phone, and soon there will be apps that tweak e-mail for the watch. The storyline appears not only with productivity tools like email, but also with predictive apps (which use algorithms to make recommendations based on context or behavior, like Pandora) and social apps (like Pinterest), too.

By contrast, discontinuous opportunities will arise for those who see the watch as distinctive. For instance, what does it mean to wear a computer, sensors, and accelerometers on your wrist?* How might one build new value-producing offerings based on the natural physical and cognitive behaviors that are characteristic of the way people move their arms and wrists?

Gesture-based productivity apps. Consider the way we naturally gesture as we casually chat with colleagues, deliver presentations, or brainstorm with engineers. Research shows that our gestures and brains work together as a so-called “coupled system” to advance thinking. “By materializing thought in physical gesture, we create a stable physical presence that… productively impacts the neural elements of thought and reason,” observes one study. In other words, these gestures actually help to reinforce neural pathways to and from our brains. Moreover, gesturing can have the effect of freeing up our mental resources to take on new tasks.

On the flip side, taking away a person’s ability to gesture has a drastic negative effect on a test subject’s ability to remember new information.

Potential Uses: One of the perennial challenges for any executive or entrepreneur is how to measure their own knowledge work productivity. This measurement is especially difficult on the frequent occasions when the user is not working at a computer: for example, when presenting at a strategy offsite or giving feedback to a direct report at the break station. Rather than appearing in digital format, these “offsite” cognitive outputs seemingly disappear into thin air. Using gesture as a possible indicator of productive thinking, a variety of apps could offer personalized feedback on away-from-screen trends to support a leader’s capacity to self-reflect and improve with data.

Gesture-driven predictive apps. Experimental research also shows that gestures are predictive. Increasing gestural movement can signal that a mental task or decision is becoming tougher to solve or understand — a dynamic suggested when we call a concept “tough to grasp.”

In these instances, gestures seem to warm-up (or preshape) our thinking for the mental heavy-lifting and learning ahead.

Potential Uses: More and more smartphone apps learn a user’s behavior and proactively make suggestions based on context and predicted needs. For example, when it’s time to get ready to catch a return flight, an app can suggest a cab service near your hotel and then pull up your boarding pass as you arrive at the airport. Many such apps, which essentially help users outsource thinking to a cloud’s predictive intelligence, will soon be rerendered for the Apple Watch, offering similar wine in a new bottle.

By looking to the predictive powers of gesture, however, developers can enable human intelligence in practical and radical new ways. In what situations (one-on-ones, conferences, or team meetings) am I learning new and challenging things, according to the data? Are there certain days or times when I am better at tacking tough mental tasks, which would help me reorganize my schedule and work routines in a less ad hoc way? Apps that begin to answer these sorts of question will create significant value for business users.

Social-gesture apps. One person’s gesturing can have measurable influence on the brains of others, creating a social-intellectual stimulus by activating “mirror neurons” in people nearby. For instance, when scientists collaborate, researchers find that gesture is particularly helpful for highlighting and exploring potential connections between different data visualizations, quantitative charts, and CT scans.

In this sense, a gesture acts as material anchor for groups trying to turn abstract information sources into well-grounded practical insights.

Potential Uses: You can expect all the big online social networks to have an Apple Watch app ready for download, but do you really need your Twitter feed or location-based Facebook offers on your wrist? A truly differentiated offering will give users insight derived from their real-world interactions and collaborations involving data visualization — an increasingly critical skill for most workers and entrepreneurs. Here’s a fundamental question a social-gesture app may begin to address:, What type of data visualizations drive the best sales team discussions and decisions? By combining gestural data with the ability to manually input the type of data viz used, an app could indicate that the bubble chart at Monday’s meeting resulted in a quantifiably more engaging discussion than the scatter graphs and heat maps from Thursday and Friday’s meetings respectively. Moving forward, you can then test the hypothesis that your team works best around bubble charts by incorporating them more frequently into sales meetings and tracking the impact on monthly revenue production. Of course, this is just one possible use of many in the area of information sharing and analysis.

The initial wave of development for the IoT has focused on reducing the need for mental resources, especially in industrial and operational processes, that could otherwise be automated with new smart devices. When considering the potential for the IoT and wearables in corporate or start-up settings, however, the focus needs to shift back to helping people make the most of the heads on their shoulders — in some cases through the things on their the wrists.

*I’d like to thank my colleague, Keith Rollag, who explored this question with me in a recent discussion. I’d also like to refer readers to this book from Oxford University Press, which is an excellent compendium of some of the key experimental studies cited above.

October 27, 2014

Why Superstars Struggle to Bond with Their Teams

From the moment you start each workday, you’re subject to two basic human impulses: to excel and to conform.

If people in your immediate environment are amazing performers, you might be able to do both at once: By excelling, you fit the norm of your spectacular coworkers. But that’s rare. I’m pretty sure that in most work environments, as soon as you excel, you stop conforming. If you choose a high-performance path, you separate yourself from your coworkers. You’re not quite one of the bunch anymore. No matter how proud you are of your achievements, tell me it doesn’t hurt when you see your old group of friends coming back from a lunch that you somehow hadn’t known about.

I was thinking about this while reading research on the psychological and social effects not of being a high performer but of experiencing an extraordinary event, because the two situations share a few things in common. When something exciting and unusual happens to us, even if it’s random, we’ve excelled, in a way. We’re special. We no longer conform.

The research, by Gus Cooney and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard and Timothy D. Wilson of the University of Virginia, shows that after we go through an extraordinary experience, we assume that we’ll really enjoy telling the tale. But when we try, we often don’t feel so good about it. We feel separate. We sense that the group resents our excellent adventure. The study focused on experiences that are really only slightly extraordinary, such as watching an interesting video, but the results are pretty clear: A special experience distances us from other people, and the responses we see in our peers makes us feel excluded.

Jaclyn M. Jensen, an assistant professor in the Richard H. Driehaus College of Business at DePaul University, has put a different lens on what divides us from our coworkers and why. Along with Pankaj C. Patel of Ball State University and Jana L. Raver of Queen’s University in Canada, Jensen studied a large Midwestern field office of a U.S. financial services firm, using surveys to find out what was going on among coworkers — in the workrooms, during team meetings, in the lunchroom, and on email.

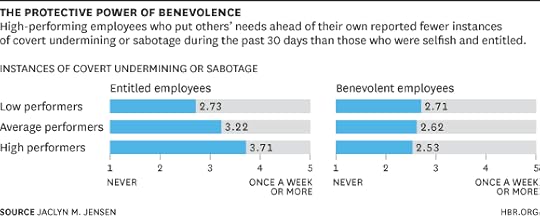

The researchers found that even in a collegial, well-behaved workplace, not only are you perceived as different if you’re a high performer; you’re also sometimes victimized. High-performing employees in this environment scored 3.37 on a 1-to-5 scale of victimization frequency, with 1 representing “never” and 5 representing “once a week or more.” They scored significantly higher on this measure of being victimized than average and poorly performing workers.

Mostly, the victimization was subtle, which is understandable, given the risks of being called out as a bully. So instead of being overtly nasty, people avoid you or withhold resources. Or they schedule important meetings when you happen to be out of town.

It probably goes without saying that there’s no rational logic to the victimization of high performers. After all, if you’re a high performer, by definition you have an outsized impact on the organization, and you help make the workgroup shine. Your victimizers’ incentive pay is probably even based (at least in part) on your achievements.

Still, what’s rational about human behavior? As Jensen pointed out to me, human beings have a pronounced tendency to punish those who violate unspoken norms. Average performers worry that you’re making them look bad. If they can bring you down a notch, they can alleviate (or at least they think they can alleviate) their negative feelings by reminding you what an “acceptable” level of performance looks like.

But one of the more interesting aspects of Jensen’s research is that the covert victimization is spotty — it doesn’t apply to all high performers. Certain achievers are spared the worst of the victimization. These are what Jensen and her colleagues call “benevolent” high performers.

Benevolent high performers are sensitive to what’s fair for other people; they put others’ needs ahead of their own. They’re cooperative, even altruistic at times.

OK, no great news there. But the reality is that high performers too often slip into what Jensen would call “non-benevolence” without even realizing it. They start to feel entitled to their hard-won authority. Sometimes they step on or manipulate others, telling themselves that all’s fair in pursuit of the greater good. Pretty soon they’re consistently putting their own needs first. To measure this, the researchers used the surveys to place employees along a continuum of behavior, with “entitled” at one end and “benevolent” at the other. Here “entitled” means having “low equity sensitivity” — a poor sense of what’s fair to others. (As you can see from the chart, low achievers are victimized too, but the researchers found that there’s a different rationale: Weak performers are punished for jeopardizing their coworkers’ success. Benevolence doesn’t help them much.)

So if you’re a high performer who’s being excluded or cold-shouldered, maybe it’s not so much your excellence that your coworkers are reacting to but your creeping non-benevolence. If they’re not looping you into lunch invites, maybe it’s because they’re starting to sense that you’re putting your own needs ahead of theirs.

If that’s the case, you know what to do. Jensen’s research shows that practicing thoughtfulness and cooperativeness really does work to defuse your colleagues’ impulse to take you down.

Cooney et al frame the issue as black and white. They write that there’s a basic conflict between our desires to “do what other people have not yet done and to be just like everyone else,” so that if we satisfy our impulse to stand out, we can’t conform any longer, and failure to conform leads to feelings of exclusion.

Jensen’s view suggests a different way of looking at it: Even if your high performance puts you on another plane, separating you from your old bunch, that nonconformity doesn’t have to come with the punishments of rejection or sniping. If you make an effort to be altruistic, the group will reward you. If not with lunch invitations, then at least with acceptance — a kind of benevolence of its own.

October 24, 2014

The Internet of Things Will Change Your Company, Not Just Your Products

I have had a front row seat as companies have struggled to enter the emerging world of the Internet of Things — first, 10 years ago as a vice president at Ambient Devices, an MIT Media Lab spinoff that was a pioneer in commercializing IoT devices, and then as a consultant.

One of the biggest obstacles is that traditional functional departments often can’t meet the needs of IoT business models and have to evolve. Here are some of the challenges that I’ve observed:

Product management. Successful IoT plays require more than simply adding connectivity to a product and charging for service — something many companies don’t immediately understand. Building an IoT offering requires design thinking from the get-go. Specifically, it requires reimagining the business you are in, empathizing with your target customers and their challenges, and creatively determining how to most effectively solve their problems.

A company that understood this was Vitality, which reimagined the pill box as a smart service to get patients to take their medications in accordance with their physicians’ instructions. So instead of creating another pill dispenser, it launched a compliance-enhancing system.

In addressing the billion-dollar adherence problem, Vitality (since acquired by NANTHEALTH) considered the interests of the players in the diverse ecosystem, including pharmaceutical companies, retail pharmacies, and health care providers. It also took into account their roles in changing patient behavior.

The resulting GlowCap offering provides continuous, real-time communication to users and caregivers via a wireless connection. Changes in light and sound indicate when it’s time to take medication. Weight sensors in the pill cylinders indicate when the medication has been removed. Accounts can be set so that text notifications or a phone call are sent if a dose is missed. By pushing a button on the device, an individual can easily order a refill from his or her pharmacy. Weekly e-mails with detailed reports can also be set up, creating a comprehensive system of medication management.

Finance. Finance teams, which are not known for their flexibility to begin with, often have trouble changing their traditional planning, budgeting, and forecasting processes to accommodate radically new IoT business models. I saw this when traditional manufacturers tried to build internet intelligence into products like refrigerators, office products, and health management devices. The finance departments of these companies struggled to account in the same set of books for both one-time revenues for product sales and the recurring subscription revenues for IoT-related services.

Finance departments also had trouble dealing with the fact that the cost of services and the resulting subscription revenues can accrue in a complex manner. Prices for IoT-related services may be based on utilization, thus creating a sliding scale of costs and revenues based on bandwidth utilization, volume of API calls, or changing hosting costs.

Forecasting and planning for product upsells, service additions, increased utilization, and churn across both products and services can also be difficult. Finally, changes in the focus of the business can quickly upend long-held key performance indicators (such as average revenue per unit or customer lifetime value) that may be core to the company’s management culture and how the business is understood.

Operations. When product-based companies add services and connectivity, operational requirements increase. The resulting challenges may include new contract-manufacturing relationships, which can be a complicated and disorienting process for the uninitiated.

The addition of third-party services and shared customer ownership can introduce tiers of customer-support challenges. Inventory requirements, warranties, and returns may change. In addition, companies may suddenly find themselves having to comply with unfamiliar laws and regulations, including those related to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and customer “Personally Identifiable Information” (confidential data such as names, addresses, contact information).

Sales. In IoT businesses, sales departments often struggle to determine how to best take a combined product and service to market. New skills may be required, new distribution options may emerge, and field conflict (direct and channel) is not uncommon. Sales operations must consider changes to market segmentation, territory management, and resource allocation. Numerous opportunities may arise for distribution partnerships, and determining how best to approach partnerships and compensation can be complicated. (Channel compensation for subscription services with recurring revenue can be a particular challenge.)

Human resources. HR has the job of developing the human capabilities needed to capture the IoT opportunity. These may involve new areas for the company (e.g., telemetry, communications and connectivity protocols, electrical hardware engineering). Building them can be an especially daunting task when the business itself is unsure of what capabilities are required.

Sometimes in IoT businesses, the answer is actually less tech and more traditional execution. My favorite example of this is iRobot, the maker of the innovative Roomba vacuum.

Rodney Brooks, a former director of the MIT Computer Science & Artificial Intelligence Lab and the co-founder of iRobot, told me that the company initially believed that robotics specialists could best explain its robotics-based offerings to the market. But it then discovered that the folks who could best distribute the offerings were vacuum industry veterans who knew the industry lingo, had existing relationships, and understood and managed the channels of distribution.

Engineering. It is rare for a single company to have all the required engineering capabilities under one roof. Consider the breadth and scope that may involve communications and connectivity technologies (telemetry, WiFi, Bluetooth, Zigbee), electrical hardware engineering (sensor technologies, chips, firmware, etc.), and design and user experience. Developing these engineering skills is one big challenge; integrating them into a functional, integrated engineering effort is another.

Since new companies built from the ground up as IoT businesses lack the departmental baggage of older firms trying to make the transition into the IoT world, the former’s learning curve is often shorter. However, the immaturity of the IoT industry means that the practices and capabilities that suffice today will not tomorrow. An ability to evolve — and to do so quickly — is a prerequisite for success.

My Dentist 3D Printed My Crown

As a tech junkie and geek wannabe I’ve been paying attention to 3D printing and the exploding maker movement. When I say paying attention, I mean reading about it, watching hackers and hobbyists make stuff, and wondering if there is more to the technology than the brightly colored plastic tchotchkes cluttering my desk. 3D printing really hasn’t affected me yet. That is until I recently chipped a tooth and had no choice but to visit my family dentist. It was the dentist’s chair that more than any article or demo converted me to the potential of 3D printing. Sometimes disruption has to hit you right in the mouth before you pay attention.

Now, I was no stranger to restorative dentistry. About seven years ago I had chipped another tooth that required a crown and didn’t remember the process fondly. It required multiple drawn out — not to mention expensive — visits to my dentist. He first had to make a physical mold of my damaged tooth. The mold was sent out to a local dental lab to manufacture a permanent crown. In the meantime, I was sent home with the inconvenience of a temporary crown made of a cured composite secured with temporary cement. Weeks later when the permanent mold was back from the lab I was summoned to the dentist for another lengthy visit to secure the new crown in place.

I wasn’t a happy camper, facing the same fate seven years later.. However, this time instead of a physical mold my dentist inserted a digital camera in my mouth and the next thing I knew a digital image of my damaged tooth immediately appeared on a computer screen positioned right next to my dental chair. My dentist knows I’m a tech junkie so he went out of his way to demonstrate his new high tech capability. I watched my damaged tooth rotating in all of its 3D glory when he ran the design software to quickly and magically fit a digital crown on top of my chipped digital tooth. Voila! He even made a few manual tweaks to the digital crown using the computer aided design software, a little bit off the side here and a little smoothing there.

It’s what happened next that blew me away and convinced me that 3D printing is a big deal. My dentist pushed send on his keyboard, then took me into another room in his dental office where he proudly pointed to a piece of equipment the size of a large microwave. The digital design of my new crown had been transmitted to a CNC (computer numerical control) milling machine. There are two basic approaches to 3D printing: printers that deposit layer after layer of materials to build an object from the ground up, and CNC milling machines which takes a block of material and carve out the desired object. I watched in awe as my crown was sculpted from a block of dental composite right before my eyes.

In about ten minutes, with my new crown in hand, it was back to the dental chair where it was expertly put in place permanently. I asked my dentist if this new capability put the dental lab that used to make routine crowns out of business. He told me he had just reviewed his budget and that he had actually increased his spending at the lab. It turns out the lab is busier than ever focusing on non-routine, higher value restorative work. At the same time, my dentist is busy delivering better value to his patients, and I got a new crown in a single visit and a life lesson in innovation.

Sometimes the most compelling use for a new technology isn’t the one that gets showed off in the expo hall or makes it onto YouTube. The plastic toys that can now be printed on demand may not matter much, but for the dentist, as for any number of other professions, the chance to design and manufacture products in house with 3D printing is already revolutionizing business.

Stop Calling People Out

Pretend that you occasionally lose your temper in meetings, and my aim is to get you to change. The next time I see you lose your cool, I say one of two things:

Hey, timeout. You just did it again — you lost your temper with Mario. This is the third time I’ve seen you do this in the last two days. C’mon, this behavior HAS to stop.

or:

Hey, can we chat for a sec? I noticed you just lost your temper with Mario. Did you notice that too? You are so good at running these meetings, I can only imagine how much more effective you’re going to be as you move past this behavior. What can I do to help?

In the first, I’m calling you out. In the second, I’m calling you forth. The content is similar. The messaging and tone are quite different. Which do you think is more effective? For most people and circumstances, it’s the latter.

If you’re a straight-shooting type of person like me (or a lawyer, philosophy major, or debate club type), you might get a cheap thrill when calling people out. It’s feels like winning a game of Gotcha!, particularly when it’s uniquely insightful. How brilliant of me to notice that and how daring to state it! Calling out can also be an emotional release. You get to be angry and superior, justifiably.

That’s the thing with calling people out. It often, not always, comes from a place of ego or reaction. The intent, conscious or not, is to make the other person wrong. There’s also a public aspect to calling someone out, of making them lose face. The tone is adversarial. And ultimately, you’re putting the burden of change entirely on the other person (“Stop it!”).

Calling people forth, in contrast, comes from a place of service and an open heart. The intent is to call the person to higher ground. It builds on their strengths. The tone is collaborative. And ultimately, you’re sharing the burden of getting better (“How can I help?”). It feels more like coaching than scolding.

Some would say calling forth is the same as using positive instead of negative reinforcement, or the “sandwich” approach to feedback. But I think it goes deeper than messaging. Calling forth is a mindset, a way of showing up as a leader who fights for the greatness within others. It starts with intention. It’s the key difference between transformational leadership and transactional leadership.

The point isn’t to be soft or to avoid conflict, it’s to be more effective. In the short term, calling forth is more motivational. In the longer term, it’s a better way to frame the relationship.

To be sure, there are situations when a heavier hand is needed. Calling out repeated safety violations may be an effective way to signal norms to others. Calling out sexist or illegal behavior may be more appropriate than a softer touch.

But as leaders, we want to build people up, not tear them down. We want to inspire our team members to levels of effectiveness that they never imagined. According to Gallup, only 13% of employees worldwide feel engaged with their work. Imagine what a 90% engagement rate would look like in terms of productivity, satisfaction, and turnover rates. But I don’t think we’ll get there if we keep calling each other out.

Engaging in a Vice Can Stimulate Creativity if It’s Framed as a Duty

In contrast to the belief that autonomy energizes us and heightens our well-being, researchers in Hong Kong found that people experience increased vitality and show greater creativity after being directed to do something — specifically, engage in a (very mild) vice. Participants who were assigned to buy a celebrity photo album (that’s the vice), as opposed to a computer-programming tutoring book, and then asked to write an ad for a bike were judged to show better creative performance than those who had been given free choice or assigned to buy the computer book (6.42 versus 5.54 and 5.72 on average, respectively, on an 11-point creativity scale), say doctoral student Fangyuan Chen and Jaideep Sengupta of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Framing a pleasure as a requirement reduces the guilt associated with it — thus the increased creativity and sense of well-being, the researchers say.

What It Will Take to Change the Culture of Wall Street

William C. Dudley, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, gave a speech Monday in which he used the word “culture” 45 times. Here’s how he defined it:

Culture relates to the implicit norms that guide behavior in the absence of regulations or compliance rules—and sometimes despite those explicit restraints. … Culture reflects the prevailing attitudes and behaviors within a firm. It is how people react not only to black and white, but to all of the shades of grey. Like a gentle breeze, culture may be hard to see, but you can feel it. Culture relates to what “should” I do, and not to what “can” I do.

Dudley has a doctorate in economics, and spent a decade as chief economist at Goldman Sachs. But in his remarks he sounded more like a sociologist than an economist. His many mentions of “culture” could be significant. I’m hoping they mark the beginning of a change in how regulators think about reining in law-breaking and excessive risk-taking at banks. I’m also hoping that I had something to do with them.

I studied economics too, as an undergraduate. Then I went to work at Goldman Sachs, in mergers and acquisitions first, proprietary trading later. I spent a dozen years there — a tenure that overlapped with Dudley’s — went on to work at several other firms, and then, after the financial crisis, decided to go back to school. I now have a Ph.D. in sociology from Columbia University and teach at Columbia Business School.

Many people find it peculiar that a former proprietary trader with a background in economics would go back to school and study sociology. As I reflected upon my career at Goldman Sachs, though, what stood out was the importance of its organizational structure. That’s something sociologists pay a lot of attention to, while economists generally don’t.

So I studied sociology, and for my doctoral dissertation focused on the organizational culture of Goldman Sachs. The dissertation became a book, titled What Happened to Goldman Sachs: An Insider’s Story of Organizational Drift and Its Unintended Consequences (HBR Press, 2013). One of the changes I document in the book is how Goldman drifted from a focus on ethical standards of behavior to legal ones — from what one “should” do to what one “can” do.

After the book was published, Dudley got in touch. I met with him and his people, and discussed what I had learned in my study of sociology and, in particular, my in-depth study of Goldman. I made recommendations on how to improve regulation. Also, I sent him two pieces I wrote for HBR.org, one on the importance of focusing on organizational behavior and not just individuals, the other asserting that culture had more to do with the financial crisis than leverage ratios did.

One of the key conclusions I drew from my study was that to achieve sustained success and avoid firm-endangering risks, a firm like Goldman has to cultivate financial interdependence among its top employees. I wrote:

Financial interdependence is important as a self-regulator … leaders should disproportionately and jointly share in fines, settlements, and other negative consequences out of their compensation plan or their stock … meaningful restrictions on leaders’ ability to sell or hedge shares should be imposed, which can lead to better self-regulating and longer-term thinking.

Consider what actually happened at JP Morgan Chase after the gigantic “London whale” trading loss. The company’s board docked the pay of CEO Jamie Dimon by more than half, to $11.5 million from $23 million. The bank also went after the bonuses of the individuals involved. That’s something, but the bulk of the loss was of course borne by shareholders. And what happened to the compensation of the typical JP Morgan managing director? According to people that I interviewed, not much (other than losses on their JP Morgan stock, which in most cases represents only a fraction of their overall net worth). The main reason, I was told, is that JP Morgan must pay competitively or lose its most talented employees. The second reason was that most managing directors had nothing directly to do with the losses.

But these people were important parts of an organization that messed up. Plus, they’d gotten big bonuses in previous years based in part on profits they had nothing to do with. One banker that I interviewed suggested that if JP Morgan’s managing directors collectively had to pay a large portion of settlements or losses related to the misbehavior out of their bonus pool, perhaps they as a group would take stronger internal actions to prevent such behavior, reward those who acted responsibly, and kick out those who did not. Maybe they would hold their leaders to higher standards and question each other’s activities.

This in fact is how things generally worked at Goldman Sachs and other Wall Street firms back when they were partnerships instead of publicly traded corporations. Each managing director was financially interdependent with every other. Typically, each received a fixed percentage of the overall annual bonus pool and was personally liable for other managing directors’ actions. At Goldman there was the added restriction that partners could not pull out their capital until after they retired (a far cry from the three-to-five-year vesting that bankers complain about today). The organizational regulation created by this structure was key to managing risk, and we should be thinking about ways to bring it back.

I am not suggesting the banks return to being private partnerships. But they should move away from today’s norm of discretionary annual bonuses for managing directors to, at least for a select group of top employees (at Goldman the elected “partner-managing directors” represent around 1.5 to 2% of total employees), a shared bonus pool with fixed percentages that would pay a large portion of settlements or losses related to misbehavior and have greater restrictions on selling stock. Managing directors would share in the firm’s successes, but also feel it when others incurred losses or when the firm got hit with fines. Giving bankers reason to hold each other accountable would cause them to pay much more attention to asking questions and managing risk and misbehavior. Restricting stock sales could push their thinking and actions in a more long-term direction.

In his speech Monday, New York Fed President Dudley urged some moves in this direction. Much of the compensation for high-level bank employees should be deferred for years, he said: “This would create a strong incentive for individuals to monitor the actions of their colleagues, and to call attention to any issues.” And when a bank is hit with a big fine, he argued — and this is something I don’t recall hearing before from a U.S. financial regulator — that some of the money be taken out of that deferred compensation pool:

Today, when a financial firm is assessed a large fine it is paid by the shareholders of the firm. Although senior management may own equity in the firm, their combined ownership share is likely small, and so management bears only a small fraction of the fine. … Assume instead that a sizeable portion of the fine is now paid for out of the firm’s deferred … compensation, with only the remaining balance paid for by shareholders. In other words, in the case of a large fine, the senior management and the material risk-takers would forfeit its performance bond.

This kind of interdependence has the potential to move the focus back to ethical standards of behavior instead of just legal ones. It might also drive away some talented employees. But if these people can’t take a longer-term approach and trust one another, should we trust them — and should they really be working at systemically important banks?

October 23, 2014

Myths About Entrepreneurship

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers