Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1350

October 20, 2014

What Apple Should Do with Its Massive Piles of Money

An Open Letter to Tim Cook, CEO of Apple

Dear Mr. Cook,

In a recent article posted on this website, I criticized Carl Icahn’s call for your company to intensify its stock buybacks. In this letter, I’d like to explain more fully why I view the $51 billion already spent by Apple on open market (including accelerated) share repurchases under your leadership as a major misallocation of resources for both the company and the U.S. economy.

Unlike Mr. Icahn, I do not write to you as an Apple shareholder (I hold no Apple shares). Nor do I write as the satisfied Apple customer that I am. Rather, I am an academic economist who, through in-depth studies of high-tech companies and industries, has come to the conclusion that stock buybacks are eroding the foundations of economic prosperity in the United States.

There is mounting evidence that buybacks bear substantial blame for the extreme concentration of income at the very top and the disappearance of middle-class jobs in the United States over the past quarter century — a topic I discussed in a recent Harvard Business Review article.

As shown in a study, “Apple’s Changing Business Model,” that I coauthored a year ago, the previous time Apple repurchased shares in significant quantities, things ended badly. From 1986 through 1993, during the Sculley era, Apple spent $1.8 billion on buybacks (67% of net income) along with $328 million on dividends (12% of net income). In 1993, Apple distributed $273 million in buybacks and $56 million in dividends, even as profits plunged from $530 million to $87 million, compelling the company to do a $297 million long-term bond issue in 1994. The next year Microsoft released Windows 95, eliminating the Mac’s longstanding GUI advantage. With losses at $816 million in 1996, Apple was forced to issue $646 million in junk bonds, supplemented in 1997 by a $150 million private issue of preference shares to Microsoft.

Fortunately for Apple, Steve Jobs returned to the company in 1997. He did not entirely eschew buybacks: The company announced a $500 million repurchase program in 1999, of which $217 million were actually completed, mostly in 1999 and 2000. But as Apple’s profits multiplied from 2004 through 2011, it was clear that, as you now call it, “” to shareholders was not a pressing priority for Mr. Jobs.

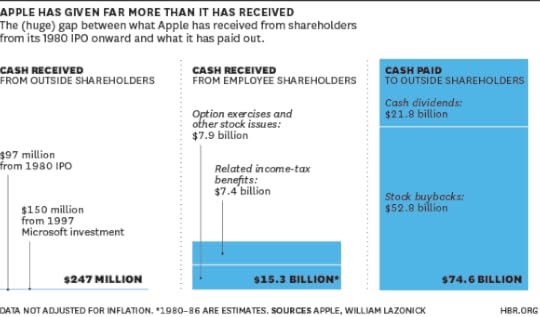

You clearly have a different point of view on distributions to shareholders. Let me ask you one simple question: How can Apple “return” capital to shareholders if those shareholders never supplied Apple with capital in the first place? As I pointed out in my earlier post, the only funds that Apple ever raised on the public stock market was $97 million (about $274 million in today’s dollars) at its IPO in 1980.

I know that finance professors at business schools throughout the nation teach MBAs and executives that, for the sake of economic efficiency, a company should “maximize shareholder value.” I disagree with this priority. MSV is based on the false assumption that, of all participants in the public corporation, only public shareholders run the risk of receiving no return on their contributions to the firm and therefore only they are entitled to profits if and when they materialize. However, there are two other important groups of people who invest in the corporation without a guaranteed return:

Taxpayers, through a wide variety of government agencies charged with spending on physical infrastructure and the nation’s knowledge base, regularly provide productive resources to companies without a guaranteed return. Through the tax system, business interests that gain from these investments return funds to the government. But tax regulations are subject to change, and hence the returns to taxpayers on their investments are by no means guaranteed.

Workers regularly make productive contributions to the companies for which they work through the exercise of skill and effort beyond those levels required to collect their current pay, and they do so without guaranteed returns. I doubt that I have to convince you, Mr. Cook, of the profound productivity difference between employees who just punch the clock to get their daily pay and those who engage in learning to make productive contributions through which they can build their careers and thereby reap future returns in work and in retirement. Yet these careers and the returns that they can generate are not guaranteed.

The irony of MSV is that the vast majority of public shareholders typically never invest in the value-creating capabilities of the company. Apple is a case in point, and it represents the rule, not the exception. Public shareholders, including Carl Icahn, do not invest in Apple’s productive capabilities. Rather, they trade in outstanding shares in the hope that their market price will increase. And, legitimized by MSV, a prime way in which corporate executives fuel this hope is by doing massive stock buybacks.

In your testimony to Congress on May 21, 2013, when you explained Apple’s tax practices, you said: “You can tell the story of Apple’s success in just one word: innovation.” I agree and ask you to consider what public shareholders and stock buybacks have to do with innovation at Apple.

Here are a few suggestions about how Apple can use its profits to support the innovation process and contribute to sustainable prosperity in the U.S. economy.

Employee education. Deepen Apple’s commitment to support the educational attainment of the company’s labor force, including those bright young people who serve in Apple Stores. I know that Apple already provides $5,000 per year to cover tuition costs for “eligible” employees. That’s nice, but it’s not enough given the current costs of higher education (a single course can cost $5,000). If Apple were to quadruple the amount per eligible employee to $20,000 (perhaps covering both tuition reimbursement and, if money is left over, an incentive subsidy to the employee for pursuing further education), I am guessing that the extra annual expense would be $600 million. That’s just 2.1% of Apple’s buybacks reported thus far for fiscal 2014. An increase in the tuition-assistance program would be a great investment in the future of Apple and the careers of its valued employees. Get rid of the buybacks, and there will be lots of money for other constructive programs to reward employees for their commitment to the company.

Employee incentives. Let performance pay do its job of incentivizing employees to invest their skills and efforts in the innovation process. Apple says that it does buybacks to offset dilution from the exercise of employee stock options or the vesting of stock awards. But what is the economic logic for this use of buybacks? Stock-based compensation is meant to motivate employees to work harder and better now to generate the competitive products that will result in higher returns for the company in the future. Therefore, rather than using corporate cash to boost Apple’s earnings per share (EPS) immediately, executives should be willing to wait for the stock-based incentives to generate higher earnings through innovation. Employees could then exercise their options or receive their vested awards at higher stock prices, and the company could allocate the increased earnings to investment in the next round of innovation. In this virtuous circle, buybacks have no role.

Social investment. When you defended Apple’s tax practices before Congress, you said: “We pay all the taxes we owe, every single dollar.” The issue for the nation is, however, whether our governments — federal, state, and local — have enough tax dollars to fund all of the public investments in infrastructure and knowledge that a prosperous nation needs. Over the past decade, our largest companies have wasted about $4 trillion on buybacks while much of America’s need for infrastructure and knowledge either went unmet or put us deeper in debt. We need CEOs like you to take the lead as responsible citizens in articulating a vision of the social investments required for the next generation. In doing so, CEOs could recognize how much their companies have gained from social investments made in the past.

Social innovation. If innovation is the story of Apple’s success, we need the widest possible diffusion of that innovation for our society to benefit. Even for the richest nation on earth, the problems of climate change, disability, discrimination, disease, pollution, poverty, and violence pose formidable challenges. To begin to solve these daunting problems, the nation needs not only Apple’s money but also Apple’s expertise — along with the organizational creativity, technological capability, and financial might of the nation’s other major business enterprises. Yes, Apple already has some sustainability initiatives in its supply chain and other areas. But it can do much more. It’s a travesty for Apple to throw away tens of billions of dollars on buybacks when it has the knowledge and power to contribute to the solution of a plethora of social ills.

I think you will agree that these suggestions are not alien to Apple’s innovative business model. But they stand in opposition to Mr. Icahn’s determination to tear that model apart. In his open letter to you he states: “Our valuation analysis tells us that Apple should trade at $203 per share today, and we believe the disconnect between that price and today’s price reflects an undervaluation anomaly that will soon disappear.”

Mr. Cook, I hope that you realize that Icahn’s valuation can be achieved only if those whose sole business is to extract value from the economy are allowed to prevail.

You and your board are in the position to decide whether that happens or not. The decisions you make will have ramifications far beyond Apple. Leading by example, you can play an important role in determining whether corporate America continues its stock-market-obsessed slide to the bottom or whether the nation can turn profits into prosperity, sustaining an innovative and inclusive race to the top.

Sincerely,

William Lazonick

Stop People from Wasting Your Time

We’re all too busy, spending our days in back-to-back meetings and our nights feverishly responding to emails. (Adam Grant, a famously responsive Wharton professor, told me that on an “average day” he’ll spend 3-4 hours answering messages.) That’s why people who waste our time have become the scourge of modern business life, hampering our productivity and annoying us in the process.

Sometimes it’s hard to escape, especially when the time-waster is your boss (one friend recalls a supervisor who “called meetings just to tell long, rambling stories about her college years” and would “chastise anyone who tried to leave and actually perform work”). But in many other situations, you can take steps to regain control of your time and your schedule. Here’s how.

State your preferred method of communication. For years, millennials have famously eschewed phone calls — but almost everyone has a communication preference of some sort. Regina Walton, a social media and community manager, told me that she, too, hates talking on the phone, a habit she developed after years of living abroad; email is almost always better for her, as “I can respond when I have time and usually am very fast to reply.” You can often limit aggravation (and harassment via multiple channels) by proactively informing colleagues about the best way to reach you, whether it’s via phone calls, texts, emails, or even tweets.

Require an agenda for meetings. Pointless or rambling meetings account for a disproportionate share of workplace time leakage. Here’s a solution: insist on seeing an agenda before you commit to attending any meeting, “to ensure I can contribute fully.” You can model the practice by writing an agenda for any meetings you chair, and offering to share the template with others. In fact, you could push to establish company norms that include best practices such as eliminating generic “updates” (which can usually be emailed in advance) and clearly indicating the decisions that need to be made as a result of the meeting. “Discuss expansion strategy” would be a murky and perhaps unproductive agenda item; “Decide whether to open a Tampa office” can guide the conversation much more clearly.

Police guest lists. Meetings are also dangerous when their list of invitees has been wantonly constructed, filled with irrelevant people and lacking decisionmakers with the authority to get things moving. If you’ve been invited, ask two critical questions. First, do I need to be there? Looking at the agenda (which you’ve insisted they provide), you can gauge whether your input would be valuable or if you can just find out details afterwards. Second, will the (other) right people be there? If you’re theoretically deciding on the Tampa expansion strategy and the executive in charge of Southeast operations isn’t in the room, it’s likely you’ll have to repeat the whole process again for her benefit. Make sure you understand who the real decisionmakers are, and don’t waste your time (or other people’s) until they can be present and participate.

Force others to prepare. We all hope and expect that others will prepare for meetings with us. Surprisingly often, they don’t. Even when they’re requesting the meeting, they may have done very little research and waste our time with extremely basic questions they could have Googled. Instead, we need to force others to prepare in advance. “Force” is a harsh word, and that’s intentional — because it’s not burdensome for people who would have prepared anyway, yet it effectively weeds out the uncommitted. Debbie Horovitch, a specialist in Google+ Hangouts, has long offered complimentary initial strategy sessions, but realized that some people were taking advantage with irrelevant discussions.

She’s adopted a new policy: “Everyone who wants a call/chat with me must fill in an application” with specific questions about what will be discussed. “Now that I’ve set my boundaries and expectations of the people I work with, it’s much easier to identify the time wasters.” Similarly, when people request informational interviews with me, I’ve begun sending them a document with links to articles I’ve written about their area of interest (becoming a consultant or speaker, reinventing their careers, etc.) and asking them to get back in touch after they’ve read them to see what questions they still have. Most never get back to me, which is just as well — I only want to speak with people who are interested and committed.

Will you face blow-back by toughening up and putting clear boundaries around your time? Inevitably. But you may also find that people start to respect you —and your time — a lot more. Most of us wish we could control our schedules better. If you’re willing to step up and argue for smarter policies (like requiring all meetings to have agendas), that benefits everyone. The key is to frame your advocacy not as purely self-interested (“I don’t have time for this nonsense”), but instead as a manifestation of your commitment to the company and your shared mission. “I want to make sure we’re all as productive as possible,” you could say, “and that’s why I think it’s important to make sure we’re respecting each other’s time.” In the end, that’s a hard message to resist.

October 17, 2014

It’s Your Job to Tell the Hard Truths

Rashid,* the CEO of a high-tech company and a client of mine for nearly a decade, called to tell me we had a major issue with some of the newer members of his leadership team.

What comes to mind when you think of what might constitute a “major issue” with some senior leaders? Maybe they’re in a fight? Maybe they’re making poor strategic decisions? Perhaps they’re not following through on commitments they made about the business? Maybe they’re being abusive to their employees? Maybe they’re stealing?

I’ve seen all of those problems in the past at various companies. But none of that was happening at Rashid’s firm. The major issue he was talking about was far more subtle — and in most places even acceptable.

Rashid had heard, through the grapevine, that two new team members were quietly questioning whether they should be honest about the gaps they saw in the business.

Is that really such a big deal? How many of us would prefer to keep the peace and avoid being the naysayer? Or prioritize being seen as a team player over identifying problems that may lie in someone else’s department? Or downplay an issue of our own team, hoping we’ll be able to fix it before anyone notices?

The truth is that it’s hard to speak up about potentially sensitive issues. But Rashid’s company’s fast growth and strong results were based, more than anything, on one underlying requirement for anyone in a leadership role: courage.

Courage underlies all smart risk taking. And no company can grow without leaders who are willing to take risks. If we don’t speak the truth about what we see and what we think, then it’s unlikely that we’ll take the smart risks necessary to lead.

So, yes, it’s a major issue if direct reports to the CEO aren’t willing to say what they really think. In fact, I’d say that there’s little value to having senior leaders in an organization who don’t speak their minds.

It’s worth asking if Rashid is creating a safe enough environment for people to speak up. That’s a good thing to consider and, in part, it’s my job to help him do that.

It’s also worth asking if the leaders have the skills to talk about sensitive topics with care and competence. This is important because it does take tremendous skill to raise hard-to-talk-about issues in a way that convinces others to address them. But, I would argue, at this point in their careers, they should have that ability. And, if they don’t, it’s easily trainable.

Ultimately, those are not the most important questions. Rashid is not running a training program or a kindergarten. He’s running a company with highly compensated leaders who are running large and complicated businesses of their own, and it’s fair for him to expect them to be brave enough to tell him what they are thinking.

How could people who have been so successful in their careers not be courageous about communicating the problems they see in a business for which they are responsible? I think that the bar for leadership in most organizations is too low. We allow politics to supersede performance. And it’s hurting good organizations.

The biggest challenge we face as leaders is rarely about discovering the perfect strategy or developing a smarter product or figuring out the gaps in the business. It’s about being courageous enough and willing to take the risks necessary to talk about the difficult, sometimes scary truth and do something about it.

That’s been the secret to Rashid’s company’s growth and the success of his leadership team. Good leaders almost always know what needs to be done. Great leaders actually do it.

So, Rashid asked, what should I do?

You have to talk to them, I said. Be direct about how you believe they’re hurting the business. Lead by example — it’s the only way.

*I’ve changed his name to protect his privacy.

What If Companies Don’t Own All That Data They’re Collecting?

Big data and the “internet of things” — in which everyday objects can send and receive data — promise revolutionary change to management and society. But their success rests on an assumption: that all the data being generated by internet companies and devices scattered across the planet belongs to the organizations collecting it. What if it doesn’t?

Alex “Sandy” Pentland, the Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences at MIT, suggests that companies don’t own the data, and that without rules defining who does, consumers will revolt, regulators will swoop down, and the internet of things will fail to reach its potential. To avoid this, Pentland has proposed a set of principles and practices to define the ownership of data and control its flow. He calls it the New Deal on Data. It’s no less ambitious than it sounds. In the November issues of HBR, Pentland discusses how the New Deal is being received and how it’s already working in a little town in the Italian Alps.

Pentland also spoke with me about these issues in a recent Google Hangout. If you missed it, you can view a recording of our conversation below:

The Real Revolution in Online Education Isn’t MOOCs

Data is confirming what we already know: recruiting is an imprecise activity, and degrees don’t communicate much about a candidate’s potential and fit. Employers need to know what a student knows and can do.

Something is clearly wrong when only 11% of business leaders — compared to 96% of chief academic officers — believe that graduates have the requisite skills for the workforce. It’s therefore unlikely that business leaders are following closely what’s going on in higher education. Even the latest hoopla around massive open online courses (MOOCs) amounts to more of the same: academics designing courses that correspond with their own interests rather than the needs of the workforce, but now doing it online.

But there is a new wave of online competency-based learning providers that has absolutely nothing to do with offering free, massive, or open courses. In fact, they’re not even building courses per se, but creating a whole new architecture of learning that has serious implications for businesses and organizations around the world.

It’s called online competency-based education, and it’s going to revolutionize the workforce.

Say a newly minted graduate with a degree in history realizes that in order to attain her dream job at Facebook, she needs some experience with social media marketing. Going back to school is not a desirable option, and many schools don’t even offer relevant courses in social media. Where is the affordable, accessible, targeted, and high-quality program that she needs to skill-up?

Online competency-based education is the key to filling in the skills gaps in the workforce. Broadly speaking, competency-based education identifies explicit learning outcomes when it comes to knowledge and the application of that knowledge. They include measurable learning objectives that empower students: this person can apply financial principles to solve business problems; this person can write memos by evaluating seemingly unrelated pieces of information; or this person can create and explain big data results using data mining skills and advanced modeling techniques.

Competencies themselves are nothing new. There are schools that have been delivering competency-based education offline for decades, but without a technological enabler, offline programs haven’t been able to take full advantage of what competencies have to offer.

A small but growing number of educational institutions such as College for America (CfA), Brandman, Capella, University of Wisconsin, Northern Arizona, and Western Governors are implementing online competency-based programs. Although many are still in nascent stages today, it is becoming clear that online competencies have the potential to create high-quality learning pathways that are affordable, scalable, and tailored to a wide variety of industries. It is likely they will only gain traction and proliferate over time.

But this isn’t vocational or career technical training nor is it the University of Phoenix. Nor is this merely about STEM-related knowledge. In fact, many of these competency-based programs have majors or a substantive core devoted to the liberal arts. And they go beyond bubble tests and machine-graded exercises. Final projects often include complex written assignments and oral presentations that demand feedback from instructors.

The key distinction is the modularization of learning. Nowhere else but in an online competency-based curriculum will you find this novel and flexible architecture. By breaking free of the constraints of the “course” as the educational unit, online competency-based providers can easily and cost-effectively stack together modules for various and emergent disciplines.

Here’s why business leaders should care: the resulting stackable credential reveals identifiable skillsets and dispositions that mean something to an employer. As opposed to the black box of the diploma, competencies lead to a more transparent system that highlights student-learning outcomes.

College transcripts reveal very little about what a student knows and can do. An employer never fully knows what it means if a student got a B+ in Social Anthropology or a C- in Geology. Most colleges measure learning in credit hours, meaning that they’re very good at telling you how long a student sat in a particular class — not what the student actually learned.

Competency-based learning flips this on its head and centers on mastery of a subject regardless of the time it takes to get there. A student cannot move on until demonstrating fluency in each competency. As a result, an employer can rest assured that when a student can use mathematical formulas to make financial decisions; the student has mastered that competency. Learning is fixed, and time is variable.

What’s more, many of these education providers are consulting with industry councils to understand better what employers are seeking. Businesses and organizations of all sizes can help build series of brief modules to skill up their existing workforce. The bundle of modules doesn’t even necessarily need to culminate in a credential or a degree because the company itself validates the learning process. Major companies like The Gap, Partners Healthcare, McDonald’s, FedEx, ConAgra Foods, Delta Dental, Kawasaki, Oakley, American Hyundai, and Blizzard are just a few of the growing number of companies diving into competencies by partnering with institutions such as Brandman, CfA, and Patten. By having built that specific learning pathway in collaboration with the education provider, the employer knows that the pipeline of students will most certainly have the requisite skills for the work ahead.

For working adults who are looking to skill-up, the advantages are obvious. These programs are already priced comparable to, or lower than, community colleges, and most offer simple subscription models so students can pay a flat rate and complete as many competencies as they wish in a set time period. Instead of having to sit for 16 weeks in a single course, a student could potentially accelerate through a year’s worth of learning in that same time. In fact, a student who was working full-time and enrolled at College for America earned an entire associate’s degree in less than 100 days. That means fewer opportunity costs and dramatic cost savings. For some, that entire degree can be covered by an employer’s tuition reimbursement program—a degree for less than $5,000. It is vital to underscore, however, that competency-based education is about mastery foremost—not speed. These pathways importantly assess and certify what a student knows and can do.

Over time, employers will be able to observe firsthand and validate whether the quality of work or outputs of their employees are markedly different with these new programs in place. Online competency-based education has the potential to provide learning experiences that drive down costs, accelerate degree completion, and produce a variety of convenient, customizable, and targeted programs for the emergent needs of our labor market.

A new world of learning lies ahead. Time to pay attention.

How to Invent the Future

We need more than big ideas, or pithy words, or an ultra-clear vision to invent the future.

Odd as it may seem for discussing innovation and management, I’m reminded of a sociology experiment done in the 1960s. Five monkeys were placed in a cage, with a batch of bananas hung from the ceiling and a ladder placed right underneath it. It took only a few seconds for one of the monkeys to race up the ladder to grab the bananas.

But the next day, whenever any of the monkeys started up the ladder, the researchers sprayed all of the monkeys with ice-cold water. Soon, each of the monkeys learned to not go up the ladder, and if any of them started to, the others would hold them back by pulling on their tail. This was done repeatedly until each little monkey had learned the lesson: no one climbs the ladder. No banana is worth it.

Once all five monkeys were conditioned to avoid the ladder, the researchers substituted in a new monkey. And wouldn’t you know it – the New Guy monkey spots the beautiful yellow bananas and goes up the ladder. But the other four monkeys – knowing the drill – jump on New Guy, and beat him up.

One by one, the researchers replaced each monkey, until none of the monkeys in the cage had been sprayed by icy water. And yet none of these new monkeys would go up the ladder, either. The rules had been set, because, “That’s just the way we do things around here.”

You know where I’m going with this story, right? Most of us are a lot like those monkeys. On the upside (and there is an upside) we learn from one another, we don’t let down our mates, and we get along. But on the downside, we don’t bother to examine the rules as they’ve been handed down.

And this downside – not examining the rules as they’ve been laid down – is not a minor thing; it has a huge cost. It stalls progress. It defeats those with fresh new ideas. It reinforces entrenched interests.

When a society accepts the practices, methods, and measures of the 20th century to conceive the 21st century, failure is inevitable. In order to consider new ideas, you have to be willing to let go of ones that no longer serve you.

The challenge, though, is not how to throw away the Old to embrace the New. That would be folly; the efficiency of the 20th century is what allows (most of) us have clean water and plenty of relatively inexpensive food to eat and so on. Plus, let’s not forget that “new” ideologies can be misleading. I’m reminded of Enron’s “new metrics” once touted by big-name thinkers as reflecting the future of management. Only later did we all collectively learn it reflected criminal accounting practices. So “new” is not the end-all. Unlike the medicine in your bathroom drawer, ideas don’t come with pre-printed expiration dates. There are no clear signs for which ones to toss and when. The challenge is in knowing how to evaluate and build new ideas into reality.

And when management thinkers are confined together in our own enclosures – not cages, but conferences – we seem to do little more than pull on each other’s tails. We find flaws in each other’s arguments (and surely there are many, for they are nascent ideas). We largely advocate for our own idea and ours alone, because we want so desperately for it to be seen. And we show why any New Idea doesn’t prove out, often without sharing our fundamental assumptions. And like the monkeys, we find ways of signaling: “That’s not the way we do things around here.”

And this approach is definitely not the way to invent the future.

So I’ve been thinking about what we’re all facing: How to deal with Change. That’s change with a capital C. Your career, your company (if you have one), and your industry are all coping with change. And with it, comes an opportunity to question what new approaches to adopt, and what to do with existing frameworks and ideas. In this social era, when connected humans can now do what once only large organizations could, the fundamentals are shifted enough, a lot of what once worked, doesn’t.

So, I think we all need a better “how” for creating ideas. It’s not enough to have the best idea, or the phrase that makes an idea go viral. Instead, what we need is a way for ideas to become powerful enough to dent the world. And no one can do that acting alone.

To figure out a way forward, let’s explore how Eric Liu, founder of Citizen University, which runs programs designed to help build the skills of effective citizenship, works on his initiative.

First, any group that joins the program has to have a shared purpose that goes beyond their own private interests. Not common strategies, but a common shared purpose, with many possibly different, most likely opposing strategies to achieve that purpose. This is why Citizen University draws leaders from both MoveOn.org and the Tea Party. They choose to come together, because they’re both leaders and activists interested in revitalizing democracy with a bottom-up, inclusive approach.

Second, the individual participants agree to build on each other’s ideas. Not as a cheerleader or a critic, but what we might call being “loyal oppositionist”: someone able to say “Here’s what’s wrong, why I think so, and one possible way to make the idea better.” As Eric says, “We ask people to not just reflexively respond, but to help one another.” Explaining why you have doubts about an idea lets everyone understand if they have different working assumptions. And proposing a solution helps advances the idea. Eric has been convening the group for three years now, and he says that one sign of success is that people keep making the effort to come back and help one another in these private forums, because people learn best and take in new ideas when they’re not “on the spot.”

Third, and underlying both points above, the conveners are inclusive of who can participate in the conversation. To hear an up and coming idea, you’ve gotta hear from many types of people, from different histories and with different experiences, so you can be challenged by newness.

It’s hard to know if Eric and the Citizen University idea will accomplish what they set out to do – to revitalize citizenship in the United States. It’ll take years for that story to play itself out. But their approach matches what I’ve seen work for innovation teams across companies. It is the “new how”, a collaborative way that shapes ideas to be better, to be stronger, and ultimately become real. To invent the future, we don’t need more ideas, or better words, or directional visions to invent the future. Instead, we need challenge common beliefs and ingrained interests. We need to stop pulling each other down by the tail and instead build up our ideas together.

This post is part of a series leading up to the annual Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 13-14 2014 in Vienna, Austria. Read the rest of the series here.

Why Does Food Taste Better if Someone Else Is Having the Same Thing?

People who ate chocolate in the presence of another person thought it tasted better if the other person had eaten the same thing, rating it 6.83 on an 11-point flavor scale versus 5.57 if the other person had been merely reading a booklet. This is even though there was no conversation about the experience, says a team at Yale led by Erica J. Boothby. Imagining another person’s feelings during a shared event may increase the cognitive resources you devote to it, thus intensifying your experience, the researchers say.

What You Eat Affects Your Productivity

Think back to your most productive workday in the past week. Now ask yourself: On that afternoon, what did you have for lunch?

When we think about the factors that contribute to workplace performance, we rarely give much consideration to food. For those of us battling to stay on top of emails, meetings, and deadlines, food is simply fuel.

But as it turns out, this analogy is misleading. The foods we eat affect us more than we realize. With fuel, you can reliably expect the same performance from your car no matter what brand of unleaded you put in your tank. Food is different. Imagine a world where filling up at Mobil meant avoiding all traffic and using BP meant driving no faster than 20 miles an hour. Would you then be so cavalier about where you purchased your gas?

Food has a direct impact on our cognitive performance, which is why a poor decision at lunch can derail an entire afternoon.

Here’s a brief rundown of why this happens. Just about everything we eat is converted by our body into glucose, which provides the energy our brains need to stay alert. When we’re running low on glucose, we have a tough time staying focused and our attention drifts. This explains why it’s hard to concentrate on an empty stomach.

So far, so obvious. Now here’s the part we rarely consider: Not all foods are processed by our bodies at the same rate. Some foods, like pasta, bread, cereal and soda, release their glucose quickly, leading to a burst of energy followed by a slump. Others, like high fat meals (think cheeseburgers and BLTs) provide more sustained energy, but require our digestive system to work harder, reducing oxygen levels in the brain and making us groggy.

Most of us know much of this intuitively, yet we don’t always make smart decisions about our diet. In part, it’s because we’re at our lowest point in both energy and self-control when deciding what to eat. French fries and mozzarella sticks are a lot more appetizing when you’re mentally drained.

Unhealthy lunch options also tend to be cheaper and faster than healthy alternatives, making them all the more alluring in the middle of a busy workday. They feel efficient. Which is where our lunchtime decisions lead us astray. We save 10 minutes now and pay for it with weaker performance the rest of the day.

So what are we to do? One thing we most certainly shouldn’t do is assume that better information will motivate us to change. Most of us are well aware that scarfing down a processed mixture of chicken bones and leftover carcasses is not a good life decision. But that doesn’t make chicken nuggets any less delicious.

No, it’s not awareness we need—it’s an action plan that makes healthy eating easier to accomplish. Here are some research-based strategies worth trying.

The first is to make your eating decisions before you get hungry. If you’re going out to lunch, choose where you’re eating in the morning, not at 12:30 PM. If you’re ordering in, decide what you’re having after a mid-morning snack. Studies show we’re a lot better at resisting salt, calories, and fat in the future than we are in the present.

Another tip: Instead of letting your glucose bottom out around lunch time, you’ll perform better by grazing throughout the day. Spikes and drops in blood sugar are both bad for productivity and bad for the brain. Smaller, more frequent meals maintain your glucose at a more consistent level than relying on a midday feast.

Finally, make healthy snacking easier to achieve than unhealthy snacking. Place a container of almonds and a selection of protein bars by your computer, near your line of vision. Use an automated subscription service, like Amazon, to restock supplies. Bring a bag of fruit to the office on Mondays so that you have them available throughout the week.

Is carrying produce to the office ambitious? For many of us, the honest answer is yes. Yet there’s reason to believe the weekly effort is justified.

Research indicates that eating fruits and vegetables throughout the day isn’t simply good for the body—it’s also beneficial for the mind. A fascinating paper in this July’s British Journal of Health Psychology highlights the extent to which food affects our day-to-day experience.

Within the study, participants reported their food consumption, mood, and behaviors over a period of 13 days. Afterwards, researchers examined the way people’s food choices influenced their daily experiences. Here was their conclusion: The more fruits and vegetables people consumed (up to 7 portions), the happier, more engaged, and more creative they tended to be.

Why? The authors offer several theories. Among them is an insight we routinely overlook when deciding what to eat for lunch: Fruits and vegetables contain vital nutrients that foster the production of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that plays a key role in the experience of curiosity, motivation, and engagement. They also provide antioxidants that minimize bodily inflammation, improve memory, and enhance mood.

Which underscores an important point: If you’re serious about achieving top workplace performance, making intelligent decisions about food is essential.

The good news is that contrary to what many of us assume, the trick to eating right is not learning to resist temptation. It’s making healthy eating the easiest possible option.

More on food, health, and productivity:

Should You Eat While You Negotiate?

Sleep Is More Important than Food

Sitting Is the Smoking of Our Generation

October 16, 2014

Disrupting TV’s Status Quo

Famed producer Norman Lear on developing groundbreaking sitcoms, managing creative partnerships and the lessons he wants to pass on to the next generation.

Numbers Show Apple Shareholders Have Already Gotten Plenty

Carl Icahn is at it again. On Oct. 9, armed with about 1% of Apple’s outstanding stock, the hedge-fund activist published an open letter to Apple CEO Tim Cook, urging him to accelerate the company’s stock repurchases by making a tender offer. I hope Cook doesn’t listen, because I think it would be bad for Apple, all of its employees who have contributed to its success, and the American economy. But judging from Cook’s past actions, I fear he will do Icahn’s bidding.

In August 2013, Icahn bought more than $1 billion worth of Apple shares. As he tweeted, he then had a “cordial dinner with Tim” the following October, during which he “pushed hard for a $150 billion buyback.”

Icahn later reduced his buyback request to $50 billion, and in April 2014 Apple’s board approved a $30 billion program to be carried out by repurchasing its shares on the open market — either by just buying shares outright or doing it indirectly via accelerated share repurchases. That was on top of a $60 billion buyback program authorized a year earlier, along with up to $40 billion in dividends. Apple’s stated intention was to carry out this $130 billion distribution of corporate cash to Apple shareholders between August 2012 and December 2015.

Since August 2012, Apple has been on a buyback binge, expending a total of $53 billion on stock repurchases through the third quarter of 2014, the last figures it has disclosed. But with his open letter to Cook, Icahn has let the public know once again that however much Apple buys back, he feels it has the current cash, borrowing capacity, and long-term profit prospects to do much, much more.

Apple is a company with phenomenal products and profits. But by jumping on the buyback bandwagon — something Steve Jobs refused to do — Apple’s current top management has shown the same lack of strategic vision that has undermined many once-great American companies, including Cisco, HP, IBM, Microsoft, and Motorola. As I explain in my recent Harvard Business Review article, “Profits Without Prosperity,” open-market repurchases that represent the vast majority of buybacks in the United States reward value extraction and undermine value creation.

Here’s an update of some key numbers in that article: In 2004-2013, 454 companies in the S&P 500 Index that were publicly listed over the decade expended $3.4 trillion on buybacks (51% of net income) and another $2.3 trillion on dividends (35% of net income). As is clear by the increasing amounts that U.S. companies, including cash-rich Apple, are borrowing to do buybacks, a large chunk of profits that is not spent on repurchases is being held abroad to avoid U.S. corporate taxation. All of this adds up to profits without prosperity in the United States.

Buybacks done through tender offers may be good for a company and the economy — when their purpose is to ensure that control over the firm’s resources remains with owner-managers who have the ability to identify growth opportunities and are committed to pursuing them. Henry Singleton, who presided over Teledyne in the 1970s, and Warren Buffet, Berkshire Hathaway’s legendary leader, are exemplars. Carl Icahn is not.

Unlike Singleton and Buffet, Icahn makes it abundantly clear that he is only interested in Apple making a tender offer for it shares in order to double their already-high price. (Since the beginning of September, Apple’s share price — adjusted for the 7-to-1 stock split that Apple did last June — has been the highest in the company’s history.) After Apple does its pump, Icahn Enterprises will do its dump.

Of Apple’s $53 billion in buybacks, $25 billion have been direct open-market repurchases (DOMRs), $26 billion accelerated share repurchases (ASRs), and $2 billion retired shares deducted from employee stock-based compensation to pay withholding taxes. Here’s how the first two work:

DOMRs: Apple repurchases stock on the open market on strategically chosen dates under SEC Rule 10b-18, presumably in amounts up to its daily “safe harbor” limit, currently $1.5 billion. It doesn’t have to disclose the dates on which it makes or has made the repurchases; it only has to report the total amount made each quarter

ASRs: Apple contracts with an investment bank to short its stock, enabling the company to retire in one fell swoop the entire amount in the contract. The bank then does the actual repurchases on the open market over time (in the case of Apple, nine months for the first $2 billion ASR and 12 months for each of two later $12 billion ASRs).

Whether done as a DOMR or ASR, the purpose of such buybacks is to give manipulative boosts to a company’s earnings per share (EPS) to help drive up its stock price. Executives can use them to increase their gains from stock-based pay.

The problem for Icahn as an outsider is that he cannot know when Apple is actually doing a DOMR or ASR. (If he were somehow privy to this inside information, it would be illegal for him to trade on it). The same applies to pension funds and mutual funds, the latter of which Icahn believes are under-invested in Apple.

He hopes that a highly visible $100 billion Apple tender offer at a price premium would convince fund managers to load up on Apple stock, helping to fuel a buying binge that would rapidly raise its price to over $200, adding in excess of $5 billion to his wealth.

What do Icahn’s machinations mean for Apple as a company that directly employs 85,000 people worldwide and for the United States as a nation that has invested in the physical infrastructure and human knowledge that have enabled Apple and other high tech companies to emerge, grow, and prosper? Massive buybacks rewards parties who have contributed the least to Apple’s products and profits. Icahn has contributed absolutely nothing to Apple’s success; nor have its public shareholders in general.

The only time in its history when Apple raised funds on the stock market was its 1980 IPO, which provided it with $97 million. In just the past two years, through buybacks, Apple has “returned” $51 billion to financial interests — the vast majority of whom never invested a penny in the productive assets of the company.

What, then, should the world’s richest company do with all those profits? I asked precisely that question in a paper, “Apple’s Changing Business Model,” that I published in September 2013, before Icahn had begun to dictate Apple’s financial policy. (Another hedge-fund activist, David Einhorn, was then playing that role). My coauthors and I argue that Apple should be returning profits to workers who have invested their time and effort into generating its products and to taxpayers who have funded the investments in the physical infrastructure and human knowledge so critical to Apple’s success.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers